Charles Wuorinen Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . . (original) (raw)

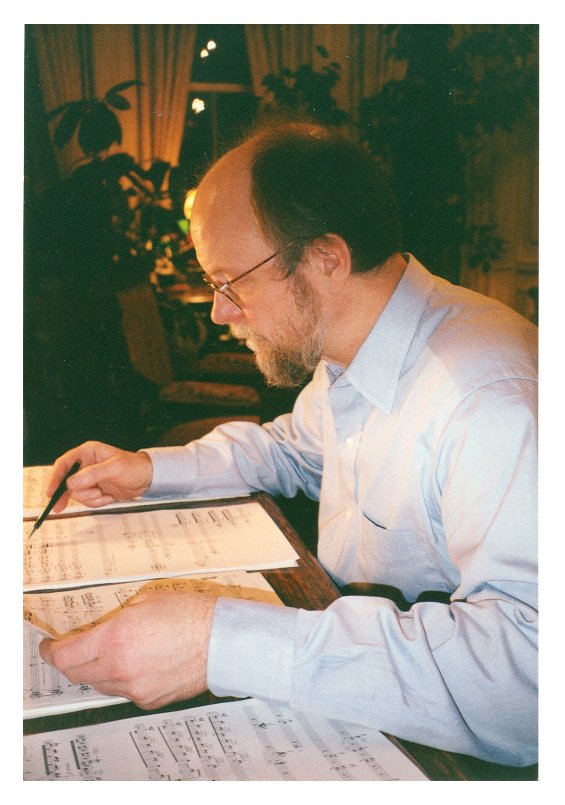

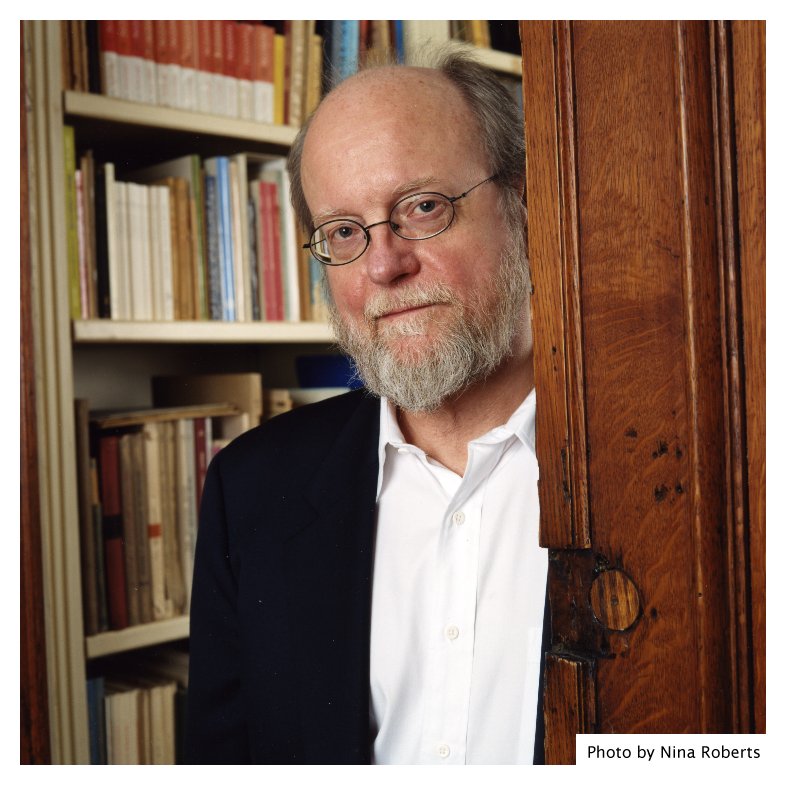

Composer Charles Wuorinen

A Conversation with Bruce Duffie

Among significant and complex composers of the late Twentieth and early Twenty-First Centuries, the place of Charles Wuorinen is secure. He is the holder of the Pulitzer Prize, as well as many other awards and honors. More importantly, though, is the respect with which he is held by the composers, performers and audiences of new music.

A short recounting of his achievements and activities is in the biography which appears at the bottom of this page, which was taken from his official website.

Wuorinen was in Chicago in February of 1987 for performances of his Third Piano Concerto with Garrick Ohlson the soloist and Michael Tilson Thomas conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. We met in one of the offices upstairs in Orchestra Hall on the afternoon before the first performance. Our encounter was amazingly easy-going, yet packed with knowledge and insight. The composer often spoke in large gestures, and his phrases encompassed major thoughts and significant ideas about music and its direction(s) in both the short and long run. His views gave scope and balance to the highest levels of achievement while never forgetting that the sounds were being absorbed by those who knew every nuance as well as those coming to the arena for the first time.

Here is what was said at that time . . . . .

Bruce Duffie: It is very gracious of you to take time from your busy schedule.

Charles Wuorinen: My pleasure.

BD: You are composer and pianist and teacher...

CW: ...Actually more conductor at this point than pianist. It takes too much time to practice, and I have too many other commitments.

BD: My question for all of this is, are you the ideal interpreter of your own works?

CW: Not necessarily. I don't say that I'm not, but it doesn't fall automatically from the fact that I have written something that I'm the person best suited to play it. In addition to the fact that there may be other people with greater mechanical skills

— certainly Garrick Ohlsson has always been a better pianist than I ever was at my best, and now it isn't even to be discussed — there is the issue of the "when" of the performance as well. I find, and I would imagine most other composers also do, that one doesn't have a constant and unchanging attitude toward one's work. As it grows older, a given piece changes its relation to its maker, and for that reason it is not at all the case that one may perform the piece the same way over and over again just because one has written it. The set of records which Stravinsky made through his life shows this very clearly, and the fiction that these performances somehow represented the definitive ideas of the master can be shown to be purely fictional just by listening to different versions of the same piece, or by comparing his performance of some of them with what is in the score.

BD: So then it's definitive for that point in time?

CW: Presumably, but I think in a broader sense one can say that once a work is finished, if it's notated to the same degree of exactness that most conventional scores are, when it leaves the hand of its author, it really takes on its own life. And while the composer certainly should be the chief authority for how it's to be done, I don't think it's necessarily the case that he should be the only one.

BD: Are you ever surprised by what you hear in performances of your works?

CW: No. If by that you mean whether certain things come out that I didn't expect, and other things don't that I did, no. I try to be careful about such things and not make errors of that sort ahead of time, so I am not surprised.

BD: Conductors never find things in your score that you didn't know you'd put there?

BD: Conductors never find things in your score that you didn't know you'd put there?

CW: That's another matter. If you're speaking purely of questions of orchestral balance

—the actual raw sound — it always comes out exactly as I've expected it. But from time to time I've found that performers — conductors — will discover motivic connections or things of that sort in my pieces that I suppose are certainly there, but that I didn't put there on purpose.

BD: These are intuitive things on your part?

CW: To a very large extent, yes.

BD: You brought up the idea of recordings. Are you pleased with the recordings that have been made of your works?

CW: Some of them yes and some of them no. It depends on the performers, obviously, and it also depends on the quality of recorded sound, although that, and I think I speak for a lot of practicing musicians, is less important to me than it probably is to most non-performing or non-composing listeners.

BD: Really, why?

CW: Because what one is interested in is the musical substance. If the sound quality itself is not as sensational as it might be, those of us who are professional musicians and spend our time practicing in the field can hear through those deficiencies, just as there are a number of people who are quite willing to listen to ancient recordings of the great performers of the past and are willing to excuse what would, by present day standards, be completely inadequate sound reproduction. But the more important reservation I have about some recordings of pieces of mine is simply ineptitude of one sort or another on the part of the performers.

BD: So you want a basic tolerable level of sound, but then you want musical judgment rather than sonic judgment.

CW: Yeah. First I want accuracy, although "accuracy" is a term which is hard to define accurately! [Both laugh] But after that, I would like musical intelligence

— such as I'm privileged to have this week in Chicago with Tilson Thomas and Garrick Ohlsson.

BD: What impact has the proliferation of the flat plastic disc

— and now the smaller plastic disc — had on the public and the performers?

CW: From a positive point of view, we all know that it's a good thing to have music more readily available than it ever was in the past. That's an obvious thing. On the negative side, it seems to me unfortunate that recorded sound has come to be the standard of musical sound rather than live sound, simply because recorded sound is the way in which most people receive music most of the time. This has, I think, a very debilitating effect on the profession

— not necessarily directly on the performers, but simply on public taste, which always has a tendency to sag down, unless it's elevated and encouraged by leadership on the part of those who are in positions of eminence and authority within the profession. By the way, we have far too little of that at the moment, in my opinion. I think one manifestation of this debilitation comes in the idiotic way in which most new halls are built. It's a great rarity if a newly built hall is not an acoustic disaster! One has to ask oneself why this is, with wonderful technical, technological, acoustical scientific equipment, and all of these measurements that are being taken, the answer is very simple — people don't listen! The most fundamental thing, which is that the damn place should sound good, requires a pair of ears that has some sense of what live music is supposed to be like!

BD: Ears instead of microphones and an oscilloscope?

CW: Yes! Exactly. All the measurements in the world, painstakingly achieved, are not going to produce the kind of sound that a person experienced with, and sensitive to, live musical sound is going to want. If it happens, well, it's an accident! There are of course other reasons for this as well, but I think this is a perfect illustration of what I'm trying to say.

BD: Is there any way of doing that as the hall is being built, or must the hall be completed before you can put the ears into it?

CW: It would seem to me that as the space is being readied, one could make tests with one's ears. Besides which, the building of good halls seems to have been a rule of thumb skill that people have had for a couple of thousand years! Why should it now be inordinately difficult to do, in the great age of precision scientific measurement? The only thing I can assign as a cause for this problem is simply that the people who design the halls can't hear anything. They don't know what anything should sound like, so they have no judgment except the non-musical, non-sonic measurements which they take, and of course those are never going to be subtle enough to do the job properly.

BD: So it's more than just the lack of the use of wood?

CW: I think so. Not to get stuck too much on this subject, but it is a big problem. I come fresh from hearing the new Carnegie Hall, with which I am not very happy, as I think most people are not. Something has been done to it, so New York now does not have a really first class concert hall anymore.

BD: They've been tinkering with Fisher Hall for years... [See my Interview with Daniel Pinkham, in which he talks about the piece he wrote as an acoustic test for Philharmonic Hall (as Avery Fisher Hall was first called when it was built in 1962).]

CW: Well, that's hopeless, I think. Not everyone agrees with me, but I think there's been definite damage done to Carnegie. It certainly is not the remarkable, giving, generous acoustic space it used to be. Maybe they need to put the curtain back.

BD: In concert music, where is the balance between art and entertainment?

CW: Wherever it is, we certainly don't have it at the moment. It's not a question of trying to achieve a balance between art and entertainment within a symphony season or on a given program, so that it'll be one part Boléro to two parts SchoenbergOpus 31, or the other way around. I think what is important is for purposes to be defined a little more clearly than they are now, and for certain temptations to be given up and to avoid running after certain chimeras so much. I don't think anyone in his right mind could possibly have an objection to entertainment! We all need it, we all want it, and there are times when it's absolutely indispensable and far more important for our lives and well-being than the highest achievements of the human race! This is understandable, and yet those highest achievements of the human race, as manifested in musical terms in the works of the great composers of the past and present may be entertaining. Some of them are, some of them are not, but all of them are demanding. I think that is the fundamental difference that one needs to draw between the two spheres. Entertainment does not demand. It presents the hearer or the viewer

— the spectator — with something that can be received without effort and can be enjoyed, whether the enjoyment consists of titillation or some other form of encounter with what is being presented. Whereas art demands a kind of active participation which entertainment does not. Art is for people who are reasonably well rested; entertainment is for people who are exhausted and need to be soothed in one form or stimulated in some effortless way. I remember discussing this kind of question with a subscriber to the San Francisco Symphony a while ago, who said, "When I get home from the office, I don't want to go to the San Francisco Symphony in the evening after a hard day's work, and have to concentrate on Boulez or something of that sort."

BD: Or Wuorinen?

CW: Or Wuorinen. He said, "What I want is Philip Glass!" [Both laugh] I responded, "This is perfectly fine, and yet do you really think that you should be going to the symphony on those evenings when you're exhausted? If what you want is a sound bath, you should find it by some other means, and not demand that artistic resources

— which are enormously expensive and effortful to operate and which have been honed over hundreds of years and are part of a rich tradition— should be the engine of your passive entertainment! There are much more effective ways that are much more fun than that." I'm not really answering your question directly, but I am saying that the balance, whatever it is, must shift according to need and mood and circumstance, but it must be preceded by a definition of purpose.

BD: Then what is the ultimate purpose of music?

CW: There are many purposes to it. There are purposes that are determined by the type of music involved. Obviously the purpose of many kinds of popular music is to offer effortless entertainment, and to make lots of money for the people who produce it, perform it and promote it! The purpose of what we normally think of as "concert music"

, beyond the usual platitudes— which are not platitudes, they're true, although clichéd, about the uplifting of the spirit and opening of the eyes and ears of the hearer into a larger and more spiritual world, and the transmission of a kind of knowledge that cannot be achieved through verbal means— beyond these vague things I can't say. What is the purpose of the Beethoven 7th Symphony? What is the purpose of The Rite of Spring? They are there. They're objects, just as one might ask what the purpose of a mountain one likes is. It is there; it is part of that life-giving and life-affirming variety without which we may as well be dead! Coming back to the other thing — because this is very much on my mind — is a question of definition of purpose in artistic institutions, since you raised the art/entertainment issue. I worry, sometimes, about our large cultural institutions in the United States. Whether one speaks of opera companies, symphony orchestras, museums, what have you, they have their tendency in many places to devote their fortunes to the effects in the practice of marketing. There comes a kind of confusion of purpose in which artistic success is measured in terms of the number of subscribers streaming into the hall, or the number of people passing through the turnstile at the museum. And this affects the size of the budget and, above all, the budgetary size of the institution. While those things are important indices and have to be kept track of, they don't represent the purpose of the institution, and yet, often, one gets the idea that artistic decisions are made the basis of these mechanistic considerations, almost in the same way that halls are sometimes built with calculator and computer, and rarely with the ear. This is the thing that we, in the United States in particular, have to watch out for, since our artistic maturity, it seems to me, is only now really upon us. As a nation or as a people, we do not automatically accept a life in the arts, a life devoted to artistic creation or reproduction or exegesis, as a natural, self-justifying activity.

BD: Should the concert management be trying to get more and more people from the pop culture into their concerts, or should we just ignore them?

CW: I don't think it's a choice, a matter of either/or. The inveiglement of the unwilling and uninterested is a terrible mistake. That is not to say that such people should be ignored. To me there is a profound difference between marketing

— advertising and promoting, which means inevitably cheapening the artistic product to groups of people who don't care about it to begin with — on the one hand, and on the other hand, making the highest artistic activities and products that people can produce available to all who want them. Access is a very different matter from promotion. Access means not only that no one could be, or would be, prevented by economic need or even, perhaps, physical location, from an encounter with the arts, but on the highest level it means, inevitably, a certain amount of information spreading — that is to say making known the availability. But there is a profound difference between saying, "We are here and we offer our artistic efforts for all who care to come," on the one hand, and on the other, a kind of sloganeering, aggressive, inevitably cheap marketing approach, which always has an effect on the artistic product. These are two very, very different things, and I don't think a proper distinction is being drawn between them. Especially for the large institutions with heavy expenses, big budgets, large staffs, and many responsibilities, there's always a temptation to look at the 50,000 people who go to rock concerts and say somewhat wistfully, "Well, we've only got three or four thousand a night; maybe we could have more." At that point, a pact begins to be drawn up with the forces of darkness. I know from my experience in various places that there begins to be a pressure placed upon artistic decisions, upon programming decisions. Since I'm speaking now mostly of symphony orchestras, the area with which I'm most familiar, a pressure builds which causes the repertoire to contract. They feel they can't have any of the even-numbered Beethoven symphonies, only the odd ones, and really not too much of 1 and 3, only 5, 7, and 9, and preferably only 9, really. They feel they could get rid of the others, and eventually you end up with Beethoven 9 one week and the 1812 Overture the next, and then back to Beethoven 9.

BD: Is there a place on the symphony program for music that is perhaps not a masterpiece?

CW: Oh, very much so, but I respond positively to that question perhaps in a way that you don't mean. I have nothing against pops concerts at all. That's perfectly fine with me, just as I have nothing against entertainment, or popular music, or any other thing that people enjoy.

BD: As long as it's billed as a pops concert?

CW: As long as the distinction is made, and as long as we don't pretend that it is something that it isn't. As long as it's done frankly and honestly, I see no reason why a symphony orchestra shouldn't be doing that sort of thing, any more than I don't see any reason why a symphony orchestra, if it wants to make money shouldn't, if it has a facility at its disposal, book in popular acts of some sort in order to help to cover its deficit. That's all fine with me; I don't care. But to come back to your question and answer it in a slightly different way, there is very much room for the non-masterpiece on the symphony program. What I mean by a non-masterpiece is not necessarily a piece of popcorn, although it might be. What I mean is the untried new work, which is quite likely not to be the greatest piece ever written. The thing that we seem never to notice about the way our concert life unfolds is that we spend most of it in a kind of necrophiliac posture with the works of the past. Anyone who is a living composer feels this very strongly. We all know new music is not nearly enough played, but there's another, slightly more subtle point about it. The music of the past, which we hear over and over again, has undergone a process of historical filtering, so that there's very little of the music of the past, very little music by dead composers which is not of the highest quality. There may be some pieces of junk that have survived for one reason or another, but they're very few indeed. Overall, when you hear music from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and even from the early 20th, you get the very best of that period. Now that has all been more or less done and taken care of, but when one comes to balancing this against the new music at whatever time we're speaking of, one has a chaotic, disorganized situation in which all kinds of people are scribbling like mad. There may be many languages with us today which are not familiar. The collective aesthetic consensuses have not been reached, and we don't have any guarantee that we're getting a certified masterpiece when we hear a new piece. The masterpiece complex, which wants every single work to be the greatest thing that has ever been composed, is not only unrealistic but extremely unhealthy. In fact, it does damage to those very masterpieces that it affects to revere! In the world of contemporary art, many more people are at work than are going to be remembered, but we have an obligation to present, certainly perhaps not everything that is scribbled down, but at least all those works that are part of the professional mainstream, which is a very broad area.

BD: Are there too many composers writing?

CW: I don't think so. Composers don't become composers because they think there's room for one more; they become composers because they have to. Ours is not a profession that you go into because you think people want it; you go into it because you must, and if you don't have the undeniable need to write music, then you shouldn't be doing it to begin with, because it's an arduous life, filled with misunderstanding, and not very remunerative.

CW: I don't think so. Composers don't become composers because they think there's room for one more; they become composers because they have to. Ours is not a profession that you go into because you think people want it; you go into it because you must, and if you don't have the undeniable need to write music, then you shouldn't be doing it to begin with, because it's an arduous life, filled with misunderstanding, and not very remunerative.

BD: For whom do you write when you sit down to compose a piece of music?

CW: It goes without saying that if one doesn't please oneself one can't please anyone else. And the evidence I've seen so far is that even those who write, let us say, the most modest and simplest kind of stuff or the most irredeemably populist music, that no one succeeds in any of these departments of musical life unless they are sincere in their efforts, and unless they have a real love for what it is they are doing. That having been said, it seems to me, from the composer's point of view, there really isn't much else that needs to be said. Of course we don't write music not to be heard! [Both chuckle] Presumably we know what it sounds like, so for our own purposes, even though it's fun to hear it, it isn't really necessary. It's a hard question to answer because it immediately raises the question of social utility. Bach wrote for God, there's no doubt of that. His music also had a function, which was very specific, and which he carried out. I seriously doubt that he gave a great deal of thought to the question of who was going to remember his work after he was gone.

BD: Do you consider that?

CW: Uhhh, probably less so than other people, but of course I consider it since I am part of a tradition, which, since the time of Beethoven, has elevated the artist as prophet, martyr, seer, rabble-rouser, revolutionary, this, that, and the other, and above all, one who makes utterances that don't evaporate within ten minutes! What the future holds, who will be remembered and who will not, is something that none of us can really say. But to return to the question of who one regards as one's public, it's a rather abstract notion. I think of certain people that I know. Some of them are not musicians who have demonstrated to me a capacity to listen intelligently, by which I mean to remember what they've heard and relate it to what's happening now at this moment in the piece. These are the people for whom I write, I suppose, if one wants to externalize. The idea of talking about the public in a general way, or trying to chart public taste, or attempting to define what "the public" wants is an exercise undertaken, usually, with negative import by a number of critics. This seems to me absolutely absurd because the musical public is so diverse, not only from nation to nation, but just taking the case of the United States, there are great differences amongst the publics who go to different kinds of musical events within the serious sphere. I'm not talking about popular music, I'm talking about those who go to opera as opposed to symphony as opposed to chamber concerts. They are different. Those who mostly buy records and don't go to concerts are different. Those who are on the East Coast are different from the West Coast, and those who are in the center of the country are different from both.

BD: Are these good differences or just differences?

CW: They're differences. There are differences of response, and there are differences of age as well. There are so many publics. They overlap a great deal, but there are so many really quite distinct and identifiable groups, that to talk about addressing one's musical message to "the public" at large, I think, is nearly meaningless.

BD: Well, what do you expect of the public that comes to hear the music of Charles Wuorinen?

CW: Obviously, the first thing I want them to do is to like it; if they do, then I'm pleased. But, as I often say to audiences when I'm asked to tell them something before they hear an unfamiliar work of mine, I think it's not very helpful, and it's anyway wrong to suggest there is a particular correct way to hear any piece. For that matter, certainly, I know there is no particular correct way to hear mine

— at least not one I have worked out to pass along to people. People have differing degrees of involvement with music, after all, and I don't think that those who have a casual relation to it, and don't want to put themselves out to a great degree, should be denied access to the higher things of life. I think they should simply accept the fact that the price they pay for not making more of an effort is simply that they get less out of it. If they're willing to accept that trade-off, then it's fine with me! But I would like to have attentive, retentive listening if I can get it.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of music?

CW: It depends on what you mean. The future of composition is always rosy because, as I said earlier, composition is undertaken by people who must do it, not people who decide they'll do that instead of becoming dentists. And given the motivation, therefore, of people who go into the actual writing of music, I have no doubt that we will continue with a stream of works of high quality. On the other hand, when one looks at the musical profession in its external sense, which of course is what most people see and most people think of when they talk about music or the world of music, I sometimes get depressed. I sometimes get worried because I see what I've started lately to call the maniacal celebration of the imbecilic on many fronts. [Both chuckle] I won't be too much more specific than that. [Despite this dismissal, he does continue] As you know, there are certain kinds of music, abroad

— which are essentially pop — which have been declared, I think quite arbitrarily, to be serious music, and which I don't think serve the cause of public understanding nor the art well at all. There are also, as I alluded to earlier, certain tendencies in the larger institutions especially — which unfortunately get imitated in the smaller, more modest ones — to make the whole life in music, the whole art of music, into a kind of product which needs to be somehow promoted and sold. People have been complaining about this for a long time, but I think it's worse now. I think that it is that loss of a connection to the art itself, to the notion of serving the art as best as one's abilities allow, to know oneself to be part of a really quite noble and very rich tradition which needs to continue to develop and to expand. It is the loss of a sense of purpose of that sort, and being caught up in yielding to short-range temptations with the promotional and marketing, these things bother me. Being immersed right in the center of it, I can't tell whether these things that concern me are a temporary state of affairs — just one more little aberration of the sort we have constantly — or if they represent a permanent shift. I am not willing to say, as was said to a colleague of mine by a record producer not long ago, that his generation — that is to say, people in their forties — were going to be the last generation who listened to serious music. I find that a little bit apocalyptic and really quite depressing. But it is very disturbing, when one takes the cause — the case of the arts as a whole, and music in particular — and looks at it in an even larger context. It is the question of what the young know now, and they don't know very much. Part of my activities involve university teaching; not a great deal of it, but I have some contact with the current generation of students, and they are utterly, abysmally, hopelessly and terrifyingly ignorant. And I don't just mean about music. These are people who have no connection whatever, as far as I can tell, with history. They know nothing of what has happened in the past. They think that ten years ago is a long time. Their sense of historical perspective is absolutely miniscule. They cannot write, they cannot speak, they cannot make complete sentences. There are, of course, some who can, but at a general level, and this is not their fault. They have been utterly betrayed by an educational system which is degenerate beyond endurance. [Takes a deep breath] As long as I'm fulminating on this subject, and to return more specifically to music, there is one more thing I could say, and that is that in the United States, insofar as there exists a difficulty between the public and new music in the specific, and serious music as a whole, it can be directly traced to music education— that is to say the lack of it, or its perversion and misapplication— in the nation's schools. Those of us who live in professional music, constantly wondering about helping people out and making them understand and love our art better, have a hopeless task. We can't do it because most of the people that we would like to reach have already been ruined by a really detestable attitude toward music manifested in the public schools. And until that is corrected — and I see no particular sign that it's going to be — until music teachers are competent in what is taught, mastering the very simple matter of learning to read music a little bit in rudimentary fashion, and then either learning a little bit of an instrument or singing, until that is done we're going to continue to have trouble.

BD: Let me ask you about your operas. There have been two, I understand?

CW: It depends on how you characterize "opera". There is one which I call a masque on Chinese topics. [The Politics of Harmony(A Masque) (1967), text by Richard Monaco, premiered by The Group for Contemporary Music, Charles Wuorinen, conductor.] And then there is another one, which is more of an official kind of opera, in two acts called The W. of Babylon, which I wrote about ten years ago and has never been performed. I am going to do in a concert version for the first time in San Francisco this coming December. [The W. of Babylon, (or The Triumph of Love over Moral Depravity) (1971-1975), text by Renaud Charles Bruce, premiered in 1987 by the San Francisco Symphony, Charles Wuorinen, conductor. Excerpts seem to have been performed at a concert on December 15, 1975, by The Group for Contemporary Music at John C. Borden Auditorium in New York City.]

BD: Why did you write it?

CW: I wrote it for practical and impractical reasons. The impractical reason was that a friend of mine who's extremely clever, had written a libretto which he badgered me over until I finally set it, which I think is very amusing. The practical matter was that I had a joint commission from the National Opera Institute and the New York State Council on the Arts, which made it possible for me to write the work. [Note: the National Opera Institute is now called the National Institute for Music Theatre.]

BD: But a performance didn't arise out of that.

CW: These institutions did not involve themselves with questions of performance, and because the score, as all my music I suppose, is difficult. But I think perhaps more important it was because the libretto is quite risqué. [Chuckles] It's taken a while to get somebody willing to do it!

BD: You had to wait for the public to catch up to it.

CW: Yes.

BD: Will you be writing any more operas?

CW: I don't have any immediate plans, but I'm certainly not against the idea.

BD: Is the future of opera different from the future of concert music?

CW: [Pensively] I don't know; isn't opera always dying? Hasn't it always been dying? [Both laugh] I really can't say since I don't work in the field that much.

BD: Every generation says that it's dead, and then it comes back.

CW: Yes, and it keeps coming back, so I honestly don't know. I think it'll go on. It's just for those who get hooked on it. I think it's simply too engaging

— in spite of all its headaches, which make ordinary music seem like absolutely nothing at all — and its enormous expense. I think it's too seductive to be given up, and I don't think it will be. It may change; it always has.

BD: When you come to performance of a work such as this one here in Chicago this week, do you help the conductor with it at all, or do you just let him get on with his work?

CW: It depends on who it is. I've worked over the years with Tilson Thomas quite a bit, and he understands my work very well, as is also true of Garrick Ohlsson, who, after all, is the person for whom the piece was written. So with these people, there's very little that I need to do by way of helping out in a general way. Of course there may be specific questions about balances, and even, perhaps, occasionally errors in the score

— although fortunately there are few of those. That kind of assistance I give. But under less favorable circumstances, I may make general comments of a certain sort to try to help a performer who doesn't really understand quite how to do the general kinds of things I've asked for.

BD: Do you ever go back and revise scores?

BD: Do you ever go back and revise scores?

CW: Almost never. In fact, I can't remember the last time I did.

BD: So there are no problems of which version to use.

CW: No. As I said earlier, I try to do it right the first time. I'm usually busy writing something else, and the idea of returning to something I've already finished is not particularly appealing to me. Some composers like to cuddle and cozy their works forever, and keep changing a little of this and a little of that until it comes out just perfect, but that is not my style.

BD: I assume that you have a lot of commissions. How do you decide which commissions you will accept and which ones you will decline?

CW: It depends on a number of things. Of course it depends on economic considerations, and it depends on the worth to me from an artistic and professional point of view of the venue. If someone wants me to write a piece for solo kazoo, and a major symphony calls the same day with a request for something, I'm likely to choose the latter rather than the former if I have to make a choice. But I have a fairly big backlog, and some of the smaller things that I'm asked to do can be delivered pretty much at my convenience. Usually I'm booked about, I would guess, two to three years ahead.

BD: Is that a good feeling, or a kind of confinement?

CW: It's better than not having anything to do, but this is in the context of an output which is three to four pieces a year, usually.

BD: I hope the piece is a success tonight.

CW: I hope so. It seems to be going quite well for the most part. We will wait and see what people think of it. But what a wonderful orchestra, needless to say! I think they really are the best. It's always a question between this one and Cleveland. I did a new work for Cleveland about two years ago, so that's fresh in my mind. [Movers and Shakers (1984), premiered by the Cleveland Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi, conductor.] You can argue one way or the other, but I think this one is better.

BD: If you write something for Chicago, is it going to be impossible to be played by other orchestras?

CW: No! This piece was originally commissioned by a consortium of regional orchestras, and was done first by the Albany Symphony.

BD: But if you're commissioned by the Chicago Symphony, would you write it differently than if you were commissioned by regional ones?

CW: I don't think so. My music is intrinsically difficult enough as it is, and one doesn't want to limit even further the possibilities for performance.

BD: You don't write it to be difficult, do you?

CW: No! That's the way it needs to be, and as a matter of fact it usually turns out over and over again that musicians say, "This is terribly difficult," when they start working on it, but it's only difficult because it's unfamiliar. Most of the difficulties are psychological rather than physical. Once they begin to find out how it goes, they say, "Oh, this is very ordinary!" You just have to count the eighth notes, or whatever.

BD: How do you know when the piece is finished?

CW: When I have nothing more to contribute to it; when I begin to feel as if my judgment is no longer contributing to the improvement of the work. That's a little difficult to say, because no matter how precise one's vision of the whole piece is before one starts to compose it, the actual reality of the notes makes for a sense of difference. It makes a different situation than what it was when contemplated in the abstract. There are always little improvements and changes of emphasis that the work can use, but I stop doing that final stage of composition at the point where it seems that choice A and choice B are equivalent. Then I know that there's nothing more that I can contribute to it.

BD: Do you know before you start how long will be?

CW: Yes, always.

BD: You're conscious of time?

CW: First of all, I normally have some kind of external circumstance imposed. Somebody wants a 15-minute piece or a half-hour piece, and I try to fulfill those time requirements...

BD: If they ask for a 15-minute piece, can it be 14 or 16, or must it be exactly 15?

CW: I'm very conscious of the difference between 14 1/2 and 15, as I would have to be, but I find that most people who say 15 minutes actually really mean is anything between ten and twenty, and they're perfectly happy. They don't mean five, but they don't mean 15 and not a penny less or more

— although they also don't mean twenty-five when they say 15.

BD: But they'll tolerate 18?

CW: They'll tolerate 18 or 13, as a rule.

BD: Is composing fun?

CW: It is for me, most of the time. Every once in a while there are really exasperating problems that come up, and in the course of life one has, as everybody does, ups and downs of a more general nature. But by and large it is! One couldn't continue doing it as much as I do. I work all the time, and I do that not because I feel driven, particularly, but because I really like doing it. So it must be fun.

BD: Do you work on one piece at a time, or a couple?

CW: That changes from one year to the next. Up to about ten years ago, I quite regularly worked on three or four things simultaneously, but that has not been the case in the last decade. It may very well come to be again, so I don't have a fixed policy about it.

BD: Thank you for being a composer!

CW: My pleasure in more ways than one.

BD: I look forward to the performance tonight, and everything else that comes from your pen!

CW: Thank you.

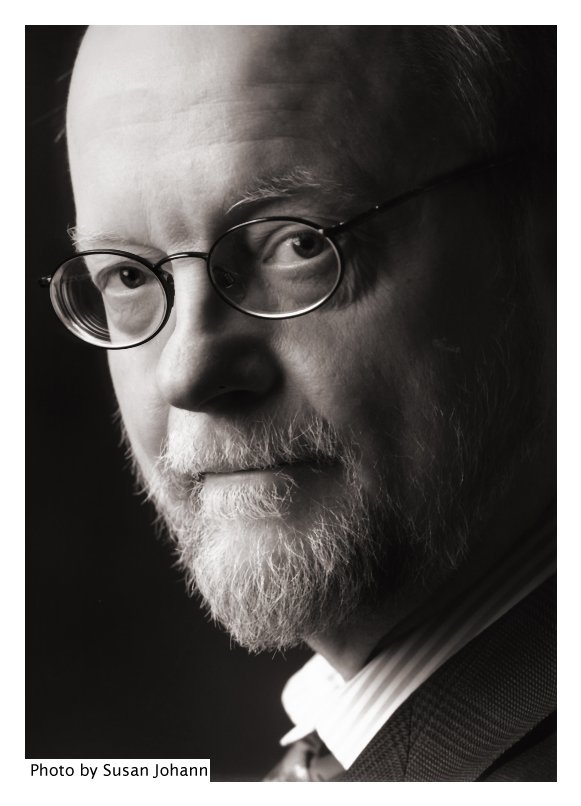

CHARLES WUORINEN (b. 9 June 1938, New York City) has been composing since he was five and he has been a forceful presence on the American musical scene for more than four decades.

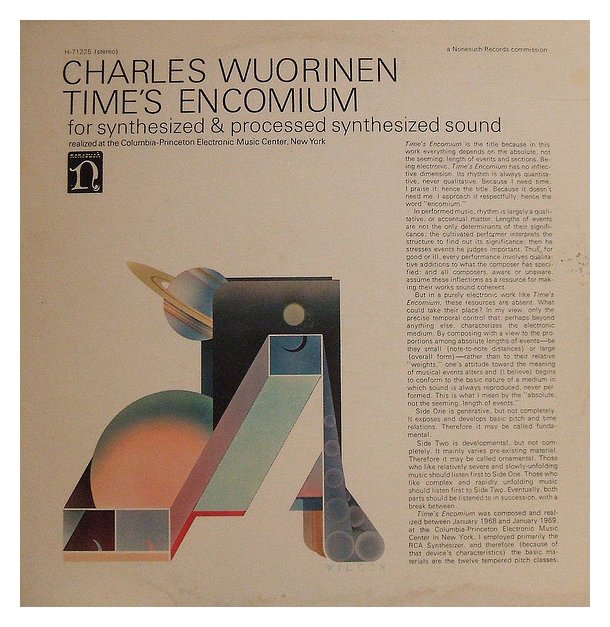

In 1970, Wuorinen became the youngest composer to win the Pulitzer Prize in music for Time's Encomium, an electronic composition written on commission from Nonesuch Records. The Pulitzer and the MacArthur Fellowship are just two among many awards, fellowships and other honors to have come his way.

Wuorinen has written more than 250 compositions to date. His newest works include It Happens Like This, a dramatic cantata on poems of James Tate to be premiered at Tanglewood in Summer 2011, Time Regained, a fantasy for piano and orchestra for Peter Serkin, James Levine and the MET Opera Orchestra, Eighth Symphony for the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Metagong for two pianos and two percussion. He is currently at work on an operatic treatment of Annie Proulx’s Brokeback Mountain to a libretto by the author. (Wuorinen’s Haroun and the Sea of Stories based on the novel of Salman Rushdie was premiered by the New York City Opera in Fall 2004.)

An indication of Wuorinen's historical importance can be seen in the fact that in 1975 Stravinsky's widow gave Wuorinen the composer's last sketches for use in A Reliquary for Igor Stravinsky. Wuorinen was the first composer commissioned by the Cleveland Orchestra under Christoph von Dohnanyi (Movers and Shakers); and likewise the first to compose for Michael Tilson Thomas' New World Symphony (Bamboula Beach). Fractal geometry and the pioneering work of Benoit Mandelbrot have played a crucial role in several of his works including Bamboula Squared and the Natural Fantasy, a work for organ.

His works have been recorded on nearly a dozen labels including several releases on Naxos, Albany Records (Charles Wuorinen Series), John Zorn’s Tzadik label, and a CD of piano works performed by Alan Feinberg on the German label Col Legno.

Wuorinen's works are published exclusively by C.F. Peters Corporation. He is the author of Simple Composition, used by composition students throughout the world.

An eloquent writer and speaker, Wuorinen has lectured at universities throughout the United States and abroad, and has served on the faculties of Columbia, Princeton, and Yale Universities, the University of Iowa, University of California (San Diego), Manhattan School of Music, New England Conservatory, State University of New York at Buffalo, and Rutgers University.

Wuorinen has also been active as performer, an excellent pianist and a distinguished conductor of his own works as well as other twentieth century repertoire. His orchestral appearances have included the Cleveland Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, New York Philharmonic, San Francisco Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, and the American Composers Orchestra.

In 1962 he co-founded the Group for Contemporary Music, one of America's most prestigious ensembles dedicated to performance of new chamber music. In addition to cultivating a new generation of performers, commissioning and premiering hundreds of new works, the Group has been a model for many similar organizations which have appeared in the United States since its founding.

Wuorinen is a member of both the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

© 1987 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded in an office upstairs at Orchestra Hall in Chicago on February 26, 1987. Portions (along with recordings) were used on WNIB in 1988, 1993, and again in 1998. An unedited copy of the audio was placed in the Archive of Contemporary Music at Northwestern University. This transcription was made and posted on this website in 2012.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award - winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was withWNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his website for more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mail with comments, questions and suggestions.