Fundamentalist Muslims Between America and Russia (original) (raw)

America is worse than Britain; Britain is worse than America. The Soviet Union is worse than both of them. They are all worse and more unclean than each other! But today it is America that we are concerned with.

- Ayatollah Khomeini, October 1964

President Reagan and General Secretary Gorbachev in Geneva in November 1985.

When President Reagan and General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev met in Geneva last November, the fundamentalist Muslim rulers of Iran devised their own interpretation of the summit conference. "The biggest worry of the two superpowers," Radio Tehran announced, "is neither the 'star wars' nor the speedy buildup of nuclear weapons, but the revolutionary uprising of the world's Muslims and the oppressed." Iran's President Sayyid Ali Khamene'i asserted that the two leaders, fearful of revolutionary Islamic ideology and the disturbing effect it has across the Third World, met to figure out "how to confront Islam." Against all evidence, the Iranians flatter themselves that much of the discussion at the summit was devoted to combating their activities.

Indeed, the rulers of Iran are convinced that the United States and the Soviet Union conspire together to keep Third World peoples in line. President Khamene'i believes that the great powers have already divided the world between them and disagree only on the exact disposition of territories. Prime Minister Mir Husayn Musavi says that the great powers are hatching joint conspiracies around the globe. In this view, the summit provided a convenient occasion for them to negotiate their small differences.

Fundamentalist Muslims offer a most peculiar interpretation of great power relationships, and they derive it from an awareness of what many in the West overlook: cultural similarities between the United States and the Soviet Union far outweigh their differences. By looking beyond political disagreements, fundamentalist Muslims see how much the two share. If American and Soviet citizens alike have difficulty recognizing themselves - or, for that matter, each other - as they are portrayed by fundamentalist Muslims, this eccentric assessment motivates a significant body of opinion through the Muslim world.

One might expect the fundamentalists' views to imply equal antipathy to the two superpowers. But this is not the case: even a cursory review of their news reports, commentaries, speeches and sermons reveals a preoccupation with America that borders on the obsessive. Although a good word is rarely said about the Soviet Union, neither is much said that is negative; the U.S.S.R. receives but a small fraction of the hatred and venom directed at the United States.

Why this imbalance? If the two great powers hatch joint conspiracies and work together to oppress the Third World and if the two states are so similar, why does America attract so much more abuse? And is there anything the United States can do to direct more of the fundamentalist hostility toward the Soviet Union?

Great Power Similarities

From the point of view of culture, the differences between the United States and the Soviet Union have only secondary importance in the eyes of fundamentalists. (For simplicity, "the United States" here includes America and its allies; "the Soviet Union" includes the entire Soviet bloc.)

Knowledgeable Muslims note what many in the West overlook: that similarities between the cultures of the United States and the Soviet Union far outweigh their differences. They see that both inherited the legacies of Greece, Rome, Christianity, Humanism, the Enlightenment and nineteenth-century rationalism. They recognize the common European origins of American liberalism and Soviet Marxism. They perceive the two people's shared conviction that Western civilization is superior to all others, as well as strong elements of anti-Muslim sentiment.

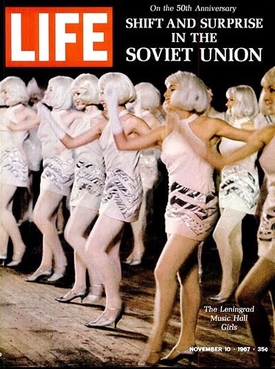

Could be Leningrad or Los Angeles.

They also note many ways the two are alike - and different from Islam. Men wear pants, women wear skirts, and everyone sits on chairs. The intelligentsia in both countries listen to the same classical music, attend the same plays and admire the same oil paintings. Of special importance is the similarity in customs relating to the sexes - all of them rejected by fundamentalist Muslims: female athletics, co-education, female employment, mixed social life, mixed swimming, dancing, dating, nightclubs, and so on.

Both powers are perceived as having similar plans for imperial expansion, continuing the scramble for colonies among the European states century ago. They see the U.S.-Soviet rivalry in terms of strategic and economic goals, not incompatible ideals. "Before, it was the British that brought us misfortune," says Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini; "now it is the Soviets on the one hand, and the Americans on the other." It hardly matters who wins this contest, for both sides aim to destroy Islamic culture and end Muslim independence. Ideally, the two giants will turn against each other and mutually exhaust themselves, thereby posing less of a threat to other peoples.

American and Soviet forces exist for the same purposes; their tanks, ships, planes and missiles look the same. Thus, the multinational peacekeeping force stationed in Lebanon from 1982 to 1984 was seen as an army of occupation no less than the Soviet troops in Afghanistan. The United States Central Command, established in 1983 to deter Soviet attacks in the Persian Gulf, looks to fundamentalist Muslims like mere camouflage for putting the instruments of American military expansion in place.

Arguments between the two powers over freedom, equality, democracy and so on have little relevance to fundamentalist Muslims. As an Egyptian member of the Muslim Brethren commented to me in 1971, "Capitalism and communism are not our concern; let the Christians fight these matters out on their own." The great powers appear to share the belief that Western civilization is superior to all others, and fundamentalists sense strong elements of anti-Muslim sentiment among Americans and Russians alike. This sentiment is not new. Bernard Lewis quotes an unidentified Turk saying during World War II, "What we would really like would be for the Germans to destroy Russia and the Allies to destroy Germany. Then we would feel safe."

Fundamentalists rejoice in being the objects of great power hostility, regarding this as proof of their independence. According to President Khamene'i, "the Americans look upon us with ill will in all matters, except with regard to subservience to the Soviets. The Russians also look upon us with ill will in all matters, except with regard to subservience to the United States. This indicates our real sovereignty."

There is an evenhanded quality to the fundamentalists' approach. They argue that Muslims should avoid close cooperation with either power: no economic concessions, political deals, or intelligence agents, much less foreign soldiers or bases, should be permitted. 'Umar at-Talmasani, an Egyptian fundamentalist, advises Muslims to "give up the United States and Russia and gird your loins.... We condemn the U.S. and Russian attitudes to us and we will reject, resist, and use every means to preserve our rights." Iran's negative neutrality is summed up by the oft-repeated slogan, "Neither East nor West."

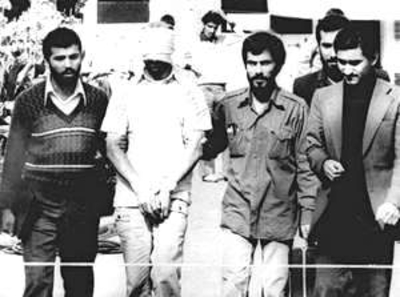

As Talmasani implies, violence is a legitimate tactic for preventing close relations with either superpower. Fundamentalist Muslims overthrew the shah's pro-Western government in Iran, then held American diplomats hostage for over a year. The presence of Americans in Saudi Arabia was one cause for the 1979 assault on the Great Mosque in Mecca. Fundamentalists ambushed American soldiers in Turkey and assassinated Anwar as-Sadat for his close ties to the United States. On a smaller scale, Iraqi fundamentalists hijacked a Kuwaiti plane in December 1984 and singled out two Americans for torture and execution. Lebanese fundamentalists began a long sequence of bombings against Americans in April 1983.

The Tehran embassy hostage crisis, 1979-81; just one of many assaults on Westerners.

The Soviet Union also feels fundamentalist opposition. Many of the mujahidin troops battling the Soviet forces in Afghanistan are fundamentalist inspired. Former President Ja'far an-Numayri of the Sudan applied the Islamic law while persecuting Sudanese communists, sparring with Soviet friends such as Ethiopia and Libya, and reducing relations with Moscow to a minimum. Syrian fundamentalists mounted a campaign of assassinations against Soviet personnel in Syria during 1979-80. Fundamentalists in Lebanon took four Soviet diplomats hostage in 1985, killing one of them.

Fundamentalists monitor the relative strengths of the Soviet Union and the United States in any given time and place, and respond accordingly. The greater its presence, the more a great power attracts the brunt of fundamentalist hostility. They opposed the Soviets in Egypt before 1973 and the Americans after that date. Saudi relations with the U.S. are condemned just as those between Libya and the U.S.S.R. Even when a great power helps Muslims in wars against non-Muslims, fundamentalists suspect its motives. Soviet aid to the Arab struggle against Israel and American aid to the Afghan rebels are seen with suspicion: the two powers, pursuing their own struggle, are only exploiting Muslims.

Four Approaches to Islam

Fundamentalist Muslims base their views on public and private life, indeed their entire existence, on the sacred law of Islam, the Shari'a. This massive body of regulations, drawn from precepts found in the Qur'an and other Islamic writings, represents the permanent goals incumbent on Muslim believers. It covers everything from personal hygiene and sexual relations, to the most public aspects of life. Among the public regulations are: a penal code based on corporal punishment, separation of the sexes, schools teaching Islamic subjects, taxes in accordance with Qur'anic levies, second-class citizenship for non-Muslims, harmonious relations between Muslim governments, and ultimately a union of all Muslims living in peace under one ruler.

The Shari'a sets out goals so ambitious, Muslims have never been able fully to achieve them. The ban on warfare between fellow believers, for example, has been repeatedly breached, judicial procedures have almost never been followed, and criminal punishment have not been applied. Full implementation of the Shari'a has always eluded Muslims. A contrast between norm and reality pervades public life; how Muslims handle this dilemma profoundly affects their views on politics.

In centuries past, pious Muslims coped with problem of not attaining Islam's goals by lowering their sights and postulating that full application of the law would occur only in the distant future. For the meantime, they agreed, the law had to be adjusted to meet the needs of daily life. This they did by applying only those regulations that made practical sense, circumventing those that did not. Muslim religious leaders found ingenious methods to fulfill the letter of the law while getting around its spirit. For example, they devised ways to ignore the prohibition on usury, enabling pious Muslims legally to charge interest on loans.

For many centuries this pragmatic approach to religion - known as traditionalist Islam - offered Muslims a stable and immensely satisfying way of life. The traditionalist approach to Islam still holds sway in many rural areas and in the cities of remote Muslim countries such as Morocco and Yemen.

But traditionalist Islam began to lose its hold in the late eighteenth century as European expansion caused a steep decline in the power and wealth of the Muslim world. As they fell under European control, Muslims had to recognize their poverty and cultural backwardness. Many responded by looking to Europe for new ideas and methods. In the process, they forsook the well-established practices of traditionalist Islam. As Muslims increasingly experimented with new interpretations of the sacred law, traditionalism lost support in favor of three other approaches to Islam: secularism, reformism, and fundamentalism.

Secularist Muslims believe that success in the modern world requires the discarding of anything that stands in the way of emulating the West. ("The West" refers here to the Americas, Europe, and Russia - all those areas heir to European civilization.) Secularists argue for the complete withdrawal of Islamic law from the public sphere. They do not allow a man to marry more than one wife, for example, but they do permit the charging of interest. But the secularist approach alienates many Muslims, so Muslim governments rarely adopt it. The few that have include the government of Albania, which abolished religion altogether; the Turkish and South Yemeni governments, which struggle to maintain secularist principles; and the Syrian, Iraqi, and Indonesian governments, which permit many breaches in those principles.

If secularists push away the Shari'a entirely in order to embrace European civilization, reformist Muslims try to reconcile the two. To facilitate the acceptance of European practices, they interpret the Shari'a to make its precepts compatible with European ways. Reformists transform Islam into a religion that forbids polygamy, encourages science, and requires democracy. They reach many of the same conclusions as do the secularists but - to make these easier to accept - call them Islamic. For example, reformists also disallow polygamy; they justify it, however, not with reference to Western habits but by re-interpreting a key Qur'anic passage. The flexibility of reformist Islam allows any contradiction to be bridged and any policy to be justified. Its adaptability appeals to many Muslim leaders and the vast majority of them have adopted reformism. They range politically from the Saudi family (since about 1930) and Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlevi to Jamal 'Abd an-Nasir and Mu'ammar al-Qadhdhafi.

Unlike the other three schools of interpretation, fundamentalism holds that the law of Islam can and must be implemented in its every detail. It argues that the exact fulfillment of God's commands in the Shari'a is a duty incumbent on all believers, as well as the Muslims' principal source of strength. The law is as valid today, fundamentalist Muslims insist, as in past centuries. They contrast the splendor of medieval Islamic civilization with the backwardness and poverty of twentieth-century Muslims, and blame this degeneration on the West. For them, the challenge of modernity centers on the issue of how fully to apply the Islamic law in changed circumstances.

Although the fundamentalist approach has existed in Islam since the seventh century, and even gained some early political successes, it became a powerful force only in the 1920s. Fundamentalism thrives when Muslim masses seek solace from the strain of modernizing and dealing with the West. Its appeal tends to grow as the modernization process seeps down into Muslim societies. While the Muslim elites who encounter modern Europe typically respond by experimenting with secularism and reformism, the masses prefer fundamentalism. They wish to preserve accustomed ways and fundamentalism offers them the instrument to fend off European influences and practices. Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani, speaker of the Iranian parliament, stated what is on every fundamentalist's mind: "Islam is important because it is capable of defeating Western culture."

Although they appear similar and are often confused, the traditionalist and fundamentalist programs differ in many respects: Where traditionalist Islam takes human foibles into account, the fundamentalist vision demands perfection. The one is pragmatic, the other doctrinaire. Traditionalists achieved a way of life so successful, it lasted for hundreds of years without major changes; fundamentalists require so much, their way has yet to be achieved. Traditionalists follow established ways; fundamentalists are engaged in a radically new project. Accordingly, the former have no need for new books, the latter write voluminously. Traditionalism is dying, fundamentalism is in its infancy.

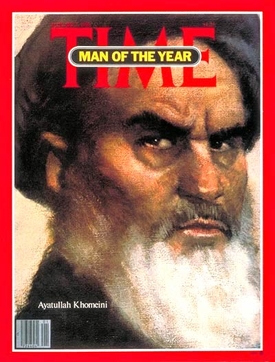

Khomeini may look medieval but he's not.

Fundamentalists believe they are returning to well-established ways and recreating an ancient way of life, though in fact they espouse a radical program that has little precedent. While a fundamentalist like Ruhollah Khomeini is often seen as "medieval," he is in fact unlike anyone who lived in past centuries. He responds to the specific challenges of the twentieth century with modern solutions. Khomeini's placing the religious authorities in charge of Iran's government, for example, has no precedent in the history of Islam; the pursuit of an Islamic economy is similarly novel. To view Khomeini as medieval is to misunderstand how profoundly he is a creature of his time.

Traditionalists do not know the West; secularists and reformists accept it in varying degrees; fundamentalists reject it. Fundamentalist Muslims, not traditionalists, secularists, or reformists, are the topic here. Fundamentalists alone consistently feel deep hostility toward the Great Powers; other Muslims subscribe to a wide diversity of views, including those very favorable to one or other of the Great Powers.

Fundamentalist Muslims and Politics

As increasing numbers of Muslims are attracted to European ways, winning them back to the Shari'a and keeping others from straying becomes the fundamentalists' preoccupation. They watch as Muslims abandon the rigors of the Shari'a after being seduced by the superficial attractions of the West. In an attempt to keep Muslims away from Western civilization, they portray it as aesthetically loathsome, ethically corrupt and morally obtuse. They whisper dark rumors of conspiracy, claiming that the West spreads its culture to weaken the Muslims and steal their resources. They ignore the West's economic and cultural achievements, harping on its unemployment and pornography. To discredit secularist and reformist Muslims, fundamentalists call them lackeys of the Western powers.

But denigrating the West is not enough. To attract lapsed Muslims, fundamentalists must imbue Islam with some of the same features that Western civilization offers. Specifically, they transform the theology and law of traditional Islam into a modern ideology, a set of economic, political and social theories. They contend that Islam contains a systematic political program comparable to, but better than, those originating in Europe. For them, liberalism leads to anarchy, Marxism to brutality, capitalism to heartlessness, socialism to poverty. In the succinct words of the Malaysian leader Anwar Ibrahim: "We are not socialist, we are not capitalist, we are Islamic." Making Islam into an ideology endows the religion with unprecedented bulk and authority. In the famous declaration by Hasan al-Banna, founder of the Muslim Brethren organization, "Islam is a faith and a ritual, a nation and a nationality, a religion and a state, spirit and deed, holy text and sword."

Differences in sect and location hardly affect the fundamentalist viewpoint. Communal disagreements aside, Shi'i and Sunni fundamentalists hardly differ in goals or methods. Though resident in different parts of the Muslim world - West Africa, the Middle East, Central Asia and Southeast Asia - fundamentalists everywhere resemble each other. When in opposition, they all pressure governments to reject Western influences; when in power they attempt to extirpate Western ways directly.

Differences that do exist reflect varying levels of commitment. The conservative fundamentalists pursue normal lives and promote their ideals in peaceable ways, through missionary work, education and personal virtue. They believe in evolutionary change. Though inclined to blame current problems - poverty, military defeat, injustice, moral laxness - on the state's divergence from the sacred law, they do not rebel against the authorities. To enhance their popularity, shaky rulers sometimes appeal to conservative fundamentalists by applying the Shari'a where it can be done conveniently.

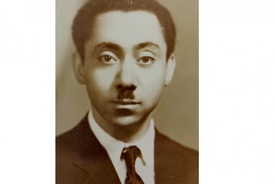

Sayyid Qutb's appearance belied his radicalism.

If conservative fundamentalists fear that the enormous appeal of Western culture erodes Islamic customs and laws, radical fundamentalists worry about the very survival of Islam. A key radical thinker, Sayyid Qutb, wrote in 1964 that the modern age presents "the most dangerous jahiliya [anti-Islamic barbarity] which has ever menaced our faith." For Qutb, "everything around is jahiliya; perceptions and beliefs, manners and morals, culture, art and literature, laws and regulations, including a good part of what we consider Islamic culture."

Consumed by the vision of a polity ordered along Islamic principles, the radicals see the existing system as illegitimate and withdraw from mainstream society. They attack their governments for ignoring the Shari'a, and claim power for themselves on the grounds that they alone aspire to implement the whole body of Islamic precepts. Extreme danger justifies extreme action; radicals pursue revolutionary change through violence. Convinced of the righteousness and the urgency of their cause, they adopt whatever means helps them achieve power, including kidnapping, assassination, bombing, and hijacking.

Although far less numerous than the conservatives, radical fundamentalists have a greater political impact. Their well-articulated program sets the agenda and their extensive infrastructure of mosques and Sufi brotherhoods poses the most acute challenge to governments. A proven willingness to use violence and a determination to succeed frequently make them invulnerable to conventional security measures. Like communists, radical fundamentalists form fronts to use others; they themselves, however, are hardly ever used or co-opted. Radicals succeeded in overthrowing the government in Iran; they present significant challenges to the authorities in Morocco, Tunisia, Nigeria, Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Numerically, fundamentalists constitute a small minority in most Muslim societies and they are embattled. Implementing the Shari'a arouses strong opposition among non-Muslims and secularist and reformist Muslims. It also alienates those other fundamentalists who would apply the law differently or want power for themselves. Meeting as they do with massive resistance, fundamentalists who achieve power suspect their opponents of the worst motives and respond with repression. This has been the pattern in the Sudan, Iran and Pakistan.

Because they are primarily concerned with a matter internal to Muslim society - the application of Islamic law - fundamentalists have but limited interest in non-Muslims. Notwithstanding their long-term plans to convert infidels and spread the rule of Islam, fundamentalists are, in the short term, defensive. Christians, Hindus and other non-Muslims are of concern only to the extent that they obstruct efforts to live by the Shari'a: culturally, by enticing individual Muslims from the law; politically, by depriving Muslim states of their independence. Fear is the key to fundamentalist attitudes toward non-Muslims; the greater they perceive a threat, the more intense their hostility.

While the threats of culture and power come from many quarters, the great powers present them most acutely. If, in fundamentalist eyes, the United States and the Soviet Union "aim to destroy the Islamic culture" and jeopardize the independence of Muslim countries, fundamentalist Muslims direct special hostility toward these two countries.

Anti-American Bias

The United States is far more worrisome for fundamentalist Muslims than the Soviet Union. Its cultural and economic influence far exceed the Soviets', its ideology is more threatening, and its intentions are seen as more hostile. In short, America presents the greater set of obstacles to life under the Islamic law.

The 1937 Mosfilm monument's socialist realism (featuring a male worker and a collective farm woman bearing a hammer and a sickle) symbolizes the studio's lack of impact outside the Soviet bloc.

Hollywood and Mosfilm. In cultural matters, the world largely ignores the Soviet Union. Who uses the Cyrillic alphabet, learns Russian, listens to Radio Moscow, watches Soviet films, attends the Central Asian State University, or vacations in the Crimea? The dreary state culture of the U.S.S.R. has virtually no impact on the Muslim world and its vibrant dissident culture does not reach there. Only pre-revolutionary culture has a presence outside the Soviet Union.

America and its allies, however, have an immense cultural impact. The Latin alphabet, English language, the BBC, Hollywood, the University of California, and the Riviera have a near-universal attraction. Whatever Americans and their government do exercises a deep fascination. American television programs and films are regularly discussed and decried. U.S. domestic issues, especially racial, criminal and economic problems, are known in detail. America's popular music, video games, comics, textbooks, literature and art reach throughout the Muslim world. Its clothing, foods, household items and machines are found in towns and villages. Most Western sexual customs, such as mixed dancing, exist in the Soviet Union as well as the United States, but they are known to Muslims around the world from the latter; some abhorred practices, say pornography or beauty pageants, exist only in the United States.

American influence also touches Muslims in more profound ways. In the delicate area of religion, America exports both Christianity (the traditional rival of Islam) and secularism (its modern rival). Christian missionaries - all but forgotten in the United States and Western Europe - loom large for the fundamentalists, who see them as leaders of a systematic assault on Islam. Fundamentalists discern a strong crusading component to U.S. foreign policy. "The U.S. attitude is motivated by several factors, but the most important, in my view," writes 'Umar at-Talmasani, the Egyptian fundamentalist leader, "is religious fanaticism.... This attitude is a continuation of the crusader invasion of a thousand years ago."

Ironically, anti-religious ideas also come from the United States. Although Moscow, not Washington, aggressively sponsors atheism, its heavy-handed, doctrinaire approach carries little weight beyond the confines of the Soviet bloc. Free-thinkers, anti-clerics and atheists the world over get their inspiration from America.

This points to a yet greater irony: Marxism itself comes to Islam mostly from the free world. Marxist thought in America and Western Europe is dynamic and in tune with new intellectual developments, whereas the version purveyed by the Soviet government is hidebound and dull. Worse, because the Soviet authorities constantly bend their ideals to meet the practical needs of being a great power, these lack intellectual honesty or even consistency. The prison writings of Antonio Gramsci have infinitely more appeal than the speeches of Brezhnev. Students sent to study in Paris, not Moscow, become the fervent Marxists. Even on the Soviet Union's own ideological turf, then, America poses the greater challenge.

Fundamentalist Muslims are convinced that journalists from both the Soviet Union and the United States try to weaken Islam by spreading misinformation about their religion. Thus, a Reuters correspondent was expelled from Iran for filing "biased and at times false reports" in May 1985. Again, while the suspicion is addressed to both camps, it is the American journalists who matter, not their Soviet counterparts. News judgments are made in New York City; the international prominence of an event depends on the emphasis given it by the editors of the major wire services, newspapers, magazines and television networks. Accordingly, Muslims know the news as it is generated in New York; they are almost oblivious of how the Soviet media cover the news.

Foreign schools are perhaps the greatest threat of all, taking impressionable young Muslims, teaching them Western languages and infecting them with alien ideas. The prominent role Christian missionaries have played historically in education makes this issue all the more alarming. Again, it is Khomeini who best expresses the fundamentalists' concern: "We are not afraid of economic sanctions or military intervention. What we are afraid of is Western universities." That which Americans see with special pride - the spread of advanced education - fundamentalist Muslims see as exceptionally dangerous.

In sum, the more attractive an alien culture, the more fundamentalist Muslims fear it and fight it.

Dollars and Rubles. Should fundamentalist Muslims seek a scapegoat for their poverty, the vast financial, industrial and commercial influence of the United States provides the obvious target. America's economic institutions cast a long shadow. Its oil producers, multinational enterprises, transportation networks and banking structures dominate their fields. American corporations beckon ambitious Muslims with lucrative jobs. The dollar is the international currency, U.S. government paper is the single greatest instrument for short-term investments, and Wall Street offers the largest capital market. The International Monetary Fund and the World Bank are widely perceived as American-dominated.

Consistent with their fear of the West, fundamentalists regard foreign economic activity in their countries as exploitative. They make quasi-Marxist arguments, claiming that the United States owes much of its prosperity to cheap labor and resources (especially oil) from the Muslim world. Foreign investments and multinational corporations are accused of skimming off the most valuable assets of Muslim countries with the help of local governments; this became especially clear in post-1979 Egypt.

In contrast, the Soviet Union has negligible economic influence. A moribund Soviet economy inspires no one to adopt its version of state capitalism as a model. The ruble has no international role. The U.S.S.R. hardly participates in the oil trade with Muslim countries and its other trade is marginal. It has almost no money to invest outside its satellites. Conversely, foreigners cannot invest in Latvian industry or Siberian mines. That the Soviet Union has so little presence in the world economy insulates it from blame; fundamentalists cannot make it the cause of their tribulations.

The presence of large numbers of Americans and West Europeans in Muslim countries exacerbates fundamentalist sensitivities. Tourists gawk, trample through sacred sites and behave immodestly. Foreign residents infect the local population with non-Islamic practices. Except for hippies, anthropologists and volunteers - each objectionable in its own way - Americans live in the best parts of town, enjoying facilities beyond the reach of most Muslims, indulging in activities forbidden by Islamic law. Several Muslim governments license establishments for drinking, gambling, and prostitution but restrict entrance to tourists and foreign residents, confirming the fundamentalists' identification of these sins with foreigners. Beaches aside for topless bathing have a similar effect. Soviet tourists are virtually non-existent outside of the Soviet bloc, while Soviet residents in Muslim countries are few in number, rarely seen, and travel in tightly supervised groups.

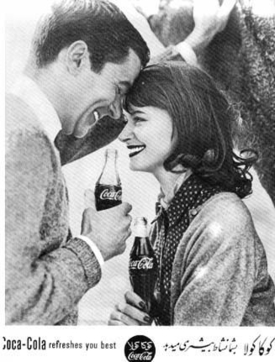

Coca-Cola was nearly ubiquitous before the Islamic revolution.

America is ubiquitous. As he walks through the modern section of almost any town, a fundamentalist Muslim would encounter and object to much of what he sees: signs in English and French, glossy advertisements promoting Marlboro cigarettes, Coca Cola and Sony electronic imports; theaters showing American feature films; kiosks carrying Time and Newsweek; luxury hotels housing American tourists; radios blaring rock music. By contrast, Russian influence derives almost exclusively from its military prowess; take that away and the Soviet international presence is very small indeed.

Liberalism and Marxism. The U.S. government represents liberal values, the Soviet government stands for Marxism as interpreted by Lenin. From the fundamentalist Muslim's point of view, these American and Soviet ideologies are about equally irreconcilable with Islamic tenets and about equally obnoxious. But the two ideologies are not equally threatening.

At first glance, liberalism appears preferable. Like Islam, it respects religious faith, the family unit and private property. Marxism, of course, abolishes these and replaces them with dialectical materialism, the state and communal ownership. A closer look, however, reveals the shallowness of this reading. Marxist attacks on the family belong to the distant past and no longer have real force. And while the Marxist rejection of private property goes much further than any views of fundamentalist Muslims, many of the latter believe in severely restricting the right of private property as a means to achieve social justice. Muhammad Baqir as-Sadr, the Iraqi thinker whose book on economics has greatly influenced the Iranian government, argues that ownership of property in Islam should be neither wholly private nor entirely public but a mix of the two. Fundamentalists fall somewhere between liberals and Marxists on the question of private property.

In one key area - religion - most fundamentalists reject Marxism, but even here the difference can be reduced. Marxist theory requires atheism, but socialism as such need not. Believers can redistribute wealth as well as atheists. Some Muslims inject God into Marxism, others produce hybrid theories of "Arab socialism" or "Islamic socialism." Fundamentalists are hopeful that Marxists will see the error of their doctrine on this point. For example, Hashemi-Rafsanjani noted recently that "as a result of the achievements of the Islamic revolution in Iran, Marxist theorists and among them Cuba's Fidel Castro, have been gradually reviewing their academic outlooks on religion and abandoning their judgment of religion as an 'opium of the masses'." Hashemi-Rafsanjani quoted Castro as saying that religion could serve as a revolutionary drive for the masses.

If fundamentalist Islam has few conflicts with Marxism, the areas of agreement between these two ideologies are numerous, especially when they are contrasted to liberalism.

- Authoritative founding scriptures. The Qur'an and the works of Marx and Engels constitute bodies of unalterable but highly malleable doctrine. Comprehensive written theories take precedence over experience and common sense. The assumption that truth is knowable permeates fundamentalist Islam and Marxism. Liberalism has no writ, no dogma, no authoritative interpreters.

- Highly specified patterns of behavior. All-embracing systems provide guidance on a wide variety of matters, great and small. Fundamentalist Islam begins with the private sphere and then extends to control the public, while Marxism moves in the other direction, but in the end both regulate private and public affairs alike. Specific regulations in the two system differ profoundly, of course, but details matter less than the fact that each of them aspires to regulate the whole of life. Liberalism leaves its citizens alone as much as possible.

- Pervasive government involvement. In the ideal Islamic or Marxist society, no activity takes place without reference to the guiding philosophy: education, art, literature, economics, law, warfare, sexuality and religion all have political significance. And if theory has something to say about every aspect of life, the government cannot be far behind. Because fundamentalist Muslims and Marxists have specific goals which require that the government shape its citizens, government becomes an instrument for molding society. Their codes incline them toward authoritarianism (government control of politics only) and even totalitarianism (government control of all aspects of life). Only a minority of fundamentalist Muslims and not all Marxists go in this direction, but the totalitarian temptation exists in both ideologies.

- Anti-individualism. Fundamentalist Muslims and Marxists share a distaste for what they view as the decadence and crass materialism of Western life. The self-indulgent and individualistic features of contemporary American life are especially worrisome. Dismissing the philosophical and political rationales behind the freedom of expression, both condemn its manifestations and, to a surprising degree, find the same manifestations most loathsome. Fundamentalist Muslim and Marxist visions of a structured society contrast with the free-wheeling, undisciplined, open way of life in America and West Europe. Individualism threatens the stability of the fundamentalist and Marxist orders in equal measure and is anathema to both. Both emphasize community need over those of the individual and place a higher priority on equality than on freedom.

- Ambitious programs. Fundamentalist Muslims and Marxists have noble-sounding visions of society that they seek to impose on their citizens. The brotherhoods of Muslims and workers should transcend geographic, linguistic, ethnic and other differences. Islam prohibits war among Muslims; Marxism demands total allegiance to the class. Islam outlaws the charging of interest on money and Marxism prohibits private profit. Islam prescribes very low taxation rates; Marxism calls for massive income redistribution. Islam calls for a society in harmony with God's laws; Marxism envisages a society in accord with "scientific" principles. Both scorn the modest, realistic expectations of liberalism, choosing to pursue higher standards.

- Inability to fulfill goals. Each system requires an impossible transformation in behavior; humans cannot live up to divine or scientific standards. Muslims and socialists alike have long clashed among themselves, starting with the Battle of the Camel in A.D. 656 (for Muslims) and the First World War (for socialists). The current division of the world into national states frustrates fundamentalists as much as Marxists. Commercial life requires interest and profits. Taxes allowed by Islam are insufficient to maintain a government, so Muslim rulers collect prohibited taxes. The income redistribution called for by Marxism undermines the social order and is rarely carried out. Unsuccessful efforts to achieve lofty goals bring on feelings of failure, which often prompts a redoubling of efforts and a turn to extreme solutions.

- Discouragement of dissent. Anyone living in a fundamentalist or Marxist order who proceeds his own way can expect to meet severe punishment. Why should those who know total truth tolerate dissent? Freedom of expression makes no sense to fundamentalists and Marxists, who discourage divergent ideas. In contrast, the liberal governments of the United States and Western Europe allow each citizen to live as he wishes (within obvious limitations) and to attempt to convince others of the truth of his ideas.

- Christianity outdated. Muslims and Marxists alike see themselves as successors to Western civilization and have mounted its only sustained challenges. Islam claims that Muhammad's revelation replaces Christianity as the final religion; Marxism claims that socialism succeeds capitalism as the final stage of economic evolution. In the face of these ambitions, the continued prosperity and power of America riles both fundamentalist Muslims and Marxists and, for all their differences, stimulates bonds between them.

For these many reasons fundamentalist Muslims find the Soviet ideological program less alien than the American. These shared traits emphatically do not imply that fundamentalist Muslims approve of Marxism, only that they have slightly more in common with Marxists than with liberals. Of course, not all fundamentalists view matters in the same way. Conservatives - who rarely follow through the logic of their thoughts - generally find liberalism less threatening. Radicals - who do follow through - prefer Marxism. The former lean toward the U.S., the latter to the U.S.S.R. Established powers tend to ally with Washington, terrorists carry Kalashnikovs.

For these many reasons fundamentalist Muslims find the Soviet ideological program less alien than the American. These shared traits emphatically do not imply that fundamentalist Muslims approve of Marxism, only that they have slightly more in common with Marxists than with liberals. Of course, not all fundamentalists view matters in the same way. Conservatives - who rarely follow through the logic of their thoughts - generally find liberalism less threatening. Radicals - who do follow through - prefer Marxism. The former lean toward the U.S., the latter to the U.S.S.R. Established powers tend to ally with Washington, terrorists carry Kalashnikovs.

White House and Kremlin. Soviet danger is not unimportant. According to the Ayatollah Khomeini, "We are at war with international communism no less than we are struggling against the global plunderers of the West... the danger represented by the communist powers is no less than that of America." He hates the Soviet Union (a "concentration camp") as much as the United States ("a brothel on a universal scale").

Indeed, one might expect fundamentalist Muslims to see the Soviet Union as their greatest threat. After all, Muscovy was already conquering Muslim lands in the fourteenth century; the Russian territorial push at the expense of Muslims continued under the tsars until the 1880s, when Moscow conquered Muslim territories in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Russian expansion into lands to the south and east constitutes the largest territorial aggrandizement in history. Although the Bolsheviks before 1917 promised independence to these regions, once in power the communist government devoted enormous resources to securing its hold on the tsarist colonial territories.

The long-term conquest of Muslim lands resumed in late 1979 with the invasion of Afghanistan. This may presage further ambitions against Muslim lands; secure control of Afghanistan would clear the way for the destabilization of Pakistan (by stimulating unrest in Baluchistan), and this would bring the Soviet Union to the Persian Gulf, with its vast oil and gas resources. Fundamentalist Muslims know the Soviet record, as the following commentary on Iranian radio makes clear:

Tsarist aspirations concerning the [Persian] Gulf region did not change in the era of the socialist October Revolution. Soviet policy adhered to the same aspirations concerning the Gulf region, its warm waters, and its strategic oil resources and the huge reserve that the region has in this respect. When the Red Army invaded Afghan territory in 1979, Moscow covered another section of the way to the region with the hope of extending it in the future.

The Soviet Union today includes within its state frontiers nearly 50 million Muslims, the only large body of Muslims still governed by a European power. Their status is similar in essential ways to that of the Indians under British rule or Algeria under French rule.

The American record could not differ more. While Moscow assembled an empire stretching from Germany to Mongolia, the United States encouraged the disbanding of European empires. From Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points in 1918 to Dwight Eisenhower's handling of the Suez crisis in 1956, American leaders pressured the British, French and other West European states to withdraw from Muslim lands. Other than the Philippines, the United States had no colonial involvement in the Eastern Hemisphere or with Muslims.

Yet American anti-imperialism seems to be forgotten when the fundamentalists examine the world around them. Fundamentalist Muslims believe they see eye-to-eye with the Soviet Union on the question of colonialism, as well as its alleged successor, neo-imperialism. They credit Moscow for helping push Great Britain, France, and the other West European states to decolonize after 1943, and good will generated by this remains. America's close relations with Great Britain and France make it, in the eyes of many Muslims, heir to their imperial mantle. Close relations with Israel, seen as part of an imperialist conspiracy, anger them.

Indeed, although the government of Iran stays aloof from both great powers (as witnessed by its slogan, "Neither East nor West"), it consistently maintains better relations with the Soviet Union. There are many reasons for this.

After independence was achieved, the U.S.S.R. provided a useful balance to America's preponderant power. As Sayyid Qutb of Egypt wrote in 1951, the Muslims "are in temporary need of the communist power." For similar reasons, the Iranian foreign minister today calls for improved political, trade and scientific relations with the U.S.S.R.

News coverage enhances the perception of the U.S. as the main threat. The smallest American act receives careful attention by everyone from U.N. ambassadors to journalists, its decision-making processes play out in public, its problems and hopes are known to all. Conversely, Soviet actions spark little interest. Russia's empire is as obscure as the film it produces: continuing efforts at the absorption of tens of millions of Muslims into Soviet society are virtually invisible. The invasion of Afghanistan attracted some attention, but only a small fraction of what a comparable American military effort would. Moscow's colonial-style control of South Yemen goes almost unnoticed. The global influence of American news media has the effect of exaggerating Washington's role and diminishing Moscow's.

This may in part account for the odd fact that the United States is even held to account for Soviet activities. When the Soviet Union established diplomatic relations with several Persian Gulf states in 1985, Iranian officials interpreted this an American ploy. "Washington is doubtlessly in the picture and background of these developments, since the U.S. monopoly of influence, in any case, leaves no room for Soviet infiltration.... [Perhaps] there is a tacit agreement between Washington and Moscow to defend the region vis-à-vis a third party [i.e. Iran] that threatens the interests of both sides." Iranian fundamentalists blame Washington for the expansion of Moscow's influence! However dangerous the Soviet Union, the United States always looks worse.

But Khomeini blames the Americans more, and his pungent anti-Americanism sets the tone for the Iranian government and affects the views of fundamentalist Muslims world wide. "Those who are creating disturbances on the streets or in the universities.... are followers of the West or the East. In my opinion, they are mostly followers of the West." In his eyes, the Russian record of expansion against Iran over the past 250 years pales in comparison with the U.S. role during the 25 years before the Islamic revolution. As he sees it, the United States put the shah in power in 1953 and kept him there through 1978. Khomeini believes that Iran in that period had become "an official colony of the U.S."

The Soviets may loom across a long border, but the Americans have already ruled the country, as the fundamentalist leadership sees it, and are planning to do so again. Khomeini believes that the United States wishes to take economic control of Iran: "Everything in our treasury has to be emptied into the pockets of America." He interprets Iraq's attack on Iran in September 1980 as an American plot and ascribes Iraq's ability to continue the war to American assistance. Iranian commentaries accuse the United States of deploying its finest "resources in the fields of politics, military and culture" against Iran. For all these reasons, Khomeini concludes, "Iran is a country effectively at war with America."

U.S. aggression toward Iran fits a larger pattern. America "has appointed its agents in both the Muslim and non-Muslim countries to deprive everyone who lives under their domination of his freedom." Make a single mistake and the Americans will pounce: "The danger that America poses is so great that if you commit the smallest oversight, you will be destroyed." In short, "American plans to destroy us, all of us." The United States is largely successful, too, at least in regard to the places Khomeini cares most about: as he stated in September 1979, "Today, the world of Islam is captive in the hands of America."

Less challenged by or aware of the Soviet Union, radical fundamentalists fear it less. In more positive terms, they slightly but consistently favor the Soviet Union over the United States. So long as America and its way of life attract traditionalist, secularist and reformist Muslims, fundamentalists will direct most of their hostility toward the United States.

U.S. Policy toward Fundamentalist Muslims

This analysis has several major implications. Of the four main reasons why fundamentalist Muslims are more anti-American than anti-Soviet, three are fixed. The cultural influence, economic dynamism and alien ideology of the United States will remain as they are, no matter who the American leaders are or what course their policy takes. No specific action will make the country less objectionable to fundamentalists. Conversely, nothing the Soviet Union can do will win it a cultural, economic or ideological role comparable to America's.

In other words, what America is, not what it does, constitutes its greatest challenge to fundamentalist Muslims. Little can be done to avert collisions between America and the fundamentalists. Were the U.S. government willing to take every step to appease the fundamentalists, most problems would remain. Disclaiming the Carter Doctrine, disbanding the Central Command, renouncing Israel, and supporting fundamentalist forces in Lebanon and Afghanistan would still leave the advertisements, ideologies, schools and multinational corporations that attract Muslims. Ultimately, Washington can do very little to reduce the fears of fundamentalists.

In other words, what America is, not what it does, constitutes its greatest challenge to fundamentalist Muslims. Little can be done to avert collisions between America and the fundamentalists. Were the U.S. government willing to take every step to appease the fundamentalists, most problems would remain. Disclaiming the Carter Doctrine, disbanding the Central Command, renouncing Israel, and supporting fundamentalist forces in Lebanon and Afghanistan would still leave the advertisements, ideologies, schools and multinational corporations that attract Muslims. Ultimately, Washington can do very little to reduce the fears of fundamentalists.

There remains one positive step open to the United States: to attempt to convince fundamentalists that with regard to the fourth factor, the political-military threat, the Soviet Union threatens them more. The fundamentalist view that the United States presents the main threat to Muslim independence is simply wrong: in fact, the Soviet Union does. Reminding the fundamentalists of basic facts - who rules 50 million Muslims in the Caucasus and Central Asia, who controls South Yemen, who has troops in Afghanistan - might increase their attention to Soviet behavior. The goals of such an effort would be modest; the point of directing attention to the Soviet empire is not to make friends for the United States, but to impress upon the fundamentalists the real nature of the dangers they face.

The American government has many means for making fundamentalist Muslim (and others) more aware of the Soviet threat: speeches by leading politicians, Voice of America programs, statements at the United Nations and other international fora, and so forth. Making the Soviet threat to Muslims a major theme would almost certainly provoke international discussion and would be much to America's benefit.

For American policymakers, the problem of dealing with fundamentalist Muslims arises in three situations: when they oppose pro-American governments, when they oppose pro-Soviet governments and when they control governments.

Opposition to pro-American governments. Tempting as it is to rush in and assist a friendly Muslim ruler facing powerful fundamentalist opposition, this often proves counter-productive. When embattled rulers accept American aid they become more vulnerable to accusations of selling their independence to Washington. The fundamentalist Muslims' extreme sensitivity to even the slightest hints of dependence on a great power renders the dilemma of helping one's friends without arousing more opposition especially acute.

To make matters worse, Muslim rulers sometimes refuse to acknowledge the full danger of arousing fundamentalist anger. The shah of Iran associated too closely with the United States; the same was true of Sadat. As secularist or reformist Muslims, these leaders were so oriented to the West that they consistently underestimated the problem of foreign contamination and the power of fundamentalists. Sadat became so absorbed by his reputation in the West - the Nobel Peace Prize, ovations from joint sessions of the U.S. Congress - that he lost touch with his own power base, the Egyptian military. Friendly Muslim leaders cannot be allowed unilaterally to expand their relationship with the United States: Americans must take part in this decision. (This problem plagues the Soviet Union and its Muslim clients as well: in Afghanistan, Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin underestimated their Islamic opposition as badly as any American allies; likewise, the Soviet leaders misunderstood the depths of resistance to their invasion.)

In assessing ties to friendly Muslim states, caution must be exercised not to make the United States unnecessarily the focus of fundamentalist anger. Fundamentalists attack what they see with their own eyes. Importing wheat prompts less animosity than the import of films and clothes. American soldiers isolated from indigenous populations pose less of a problem than soldiers stationed in cities. Quiet cooperation with a friendly government provokes less opposition than open declarations of support at public meetings. Strong relations need not have a high profile: ideally, they are almost invisible.

When communist or pro-Soviet forces threaten, pro-American regimes are tempted to promote fundamentalists as a counterweight, or even to bring them into the government. But this tactic involves great danger. The Tunisian and Egyptian governments encouraged fundamentalists in the early 1970s, only to lose control of those movements by the end of the decade. Secularist politicians in Turkey and the Sudan formed coalitions with fundamentalists in the mid-1970s, then had to accede to fundamentalist efforts to impose the Shari'a. And when a non-fundamentalist like Zulfikar 'Ali Bhutto of Pakistan tries to win fundamentalist support by imposing the Islamic law, he usually fails, for they still distrust him.

Imposition of the Shari'a creates three sources of tension with the United States. First, Americans have difficulty supporting a government that flogs alcohol-drinkers, cuts off the hands of thieves, and stones adulterers. Abhorrent to Western morals, these practices create American ill will. Second, widespread opposition to the fundamentalists' version of the law leads to an upsurge of repression and instability, and this in turn leads to anti-Americanism. Third, the strengthening of some of America's most profound antagonists inevitably sours relations with the United States.

In one way, conservative fundamentalists threaten American interests more than the radicals, for they can make their influence felt within regimes friendly to the United States, while radicals oppose the authorities too much to be tempted into a coalition. Ultimately, however, radical fundamentalists are the real danger. As seen more profound enemies of the United States than Marxists, their ascent to power almost always harms the United States and its allies. A fundamentalist Muslim regime is preferable to a Marxist one, but it threatens American interests more than almost any other alternative.

Should the United States be invited to counsel Muslim allies on the question of cooperating with the fundamentalist opposition, its advice should be straightforward. Unless special circumstances dictate otherwise, it opposes application of the Shari'a and discourages enhancing the power of fundamentalists. The United States should neither assist fundamentalist movements that oppose friendly governments nor encourage its friends to appease them. Contact with radical fundamentalists is necessary, of course, to understand their views and to monitor their influence, but no assistance should be provided.

Opposition to pro-Soviet governments. When fundamentalist Muslims oppose Soviet-backed governments, the United States is naturally tempted to provide aid to the fundamentalists. But this should only be done with utmost caution, if at all, and with full awareness of the perils involved. Even short-term aid can have dangerous consequences. Support for fundamentalists might make them the only alternative to communists; the United States can inadvertently strengthen the two extremes against the middle, squeezing out its natural allies between Soviet clients and fundamentalist Muslims. The moderates, whose views more closely correspond to America's, might be destroyed in the process.

Noting these dangers, fundamentalist Muslim groups should receive U.S. aid only when two conditions re met: the government they oppose creates very major problems for the United States; and the fundamentalists make up the only non-communist opposition.

Libya, Syria and Afghanistan all meet the first criterion. But fundamentalists are only a minor element in the opposition to Mu'ammar al-Qadhdhafi's regime; American aid should therefore go only to the non-fundamentalist opposition. In Afghanistan too, the second condition is not met, for non-fundamentalist mujahidin groups are active both in the fighting in Afghanistan and in refugee politics in Pakistan; these deserve military, political and financial support from the United States. In Syria, however, the second condition is met. The Muslim Brethren constitute the only serious opposition to the regime of Hafiz al-Asad, and they have shown determination and resourcefulness. There being no moderate force to support, Syrian fundamentalists could properly receive U.S. aid.

Fundamentalists in power. Conservatives usually seek good relations with the United States and, keeping the profound differences between their goals and those of the United States in mind, ties should be cultivated. Disagreement on long-range goals mean that cooperation with a great power is limited to tactics. Pakistan resembles China in the way it works with the United States against the Soviet Union: both countries take money and aid without giving friendship. The application of Islamic law creates human rights problems, so the United States cannot become too closely associated with fundamentalist leaders, as it did with Ja'far an-Numayri in the Sudan.

Radicals have terrible relations with the United States, and for obvious cultural, economic and ideological reasons. Notwithstanding their fears of Western civilization, the United States should do its best to make the Soviet danger to Muslim independence better known. Even so adamant an opponent as Khomeini is likely to dwell less on America as he becomes more aware of Soviet expansionism.

June 21, 1986 addendum: This quote by the Egyptian fundamentalist Sayyid Qutb ended up on the cutting room floor but should have been an epigram: "America and Russia are the same; they both base themselves on materialistic thinking. The real struggle is between Islam on the one hand and Russia and America on the other."