Don't forget your shovel (original) (raw)

Halloween South Australia style

The days are getting longer and warmer, it must be Halloween in South Australia. It’s only in recent years that it’s been celebrated here, and mainly with pumpkins and Trick or Treat. I like to keep it traditional, though, and last year I carved turnip lanterns. They were quite successful, so I thought I’d give it another go. In the picture below, you can see my two new turnips with my lanterns from last year looking on.

And now, creepily, as my new turnip lanterns develop faces, their ancestors move in closer to join them, looking for all the world like they’re passing on the wisdom they’ve gained over the past twelve months.

Just in time, they’re installed on the front door, with a friendly plastic pumpkin face to lure the unsuspecting Trick or Treaters closer.

And yes, we’re still in the middle of a pandemic, so treats are contactless and come with an advisory message to sanitise hands before choosing something.

God in a bottle in South Australia – twice!

It was only a few years ago that I first heard about the extraordinary creations known as God-in-a-bottle. So I won’t be surprised if you are crinkling up your nose in a puzzled sort of way right now. Let me put you out of your misery. The God-in-a-bottle is a Catholic object constructed along the same lines as the more usual ship-in-a-bottle – see some examples in the image below. Claudia Kinmonth (2020:415-417) says that in their most basic form, they were usually ‘a reused glass spirit, wine or mineral bottle often containing a carved wooden cross, with a ladder leaning against it inside, sometimes (but not always) filled with water’. The water was usually holy water, or at least marketed as such.

Image sourced from Kinmonth (2020:416), courtesy of Beamish, the Living Museum of the North.

Essentially, they depict the crucifixion or other religious scenes in a bottle. Sometimes they’re quite elaborate, containing the crucifixion tools such as pincers, spears or a hammer. Although they date primarily from the late nineteenth century when glass bottles were easily available, there are examples from more recent times. English examples are often associated with Irish workers on the buildings and railways of the north of England. Some featured in a 2014 Tate exhibition where they were described as ‘surreal artefacts‘.

Recently, I went snorkelling with the cuttlefish near Whyalla. That was glorious, but coming a close second was fossicking in a small antiques shop on the way home at Wirrabara. In the last room, I spied a magnificent God-in-a-bottle. It didn’t have a crucifixion scene, but it did feature both the Sacred Heart of Jesus and the Immaculate Heart of Mary. It’s in an old flagon bottle, quite a big one, more than 30 cm tall. It includes the maker’s name on a card – Peter Coleman of Adelaide. And the shop owner told me that he thought he might have worked out of the Adelaide Arcade. I haven’t been able to find out any more than that.

But this wasn’t my first South Australian God-in-a-bottle. Sevenhill Winery was established by Jesuit priests in the mid-nineteenth century. It was the first winery in the Clare Valley. It has a tiny museum next to the tasting room, and a couple of years ago, I found a God-in-a-bottle there. As you can see from the pictures below, this one portrays the crucifixion scene. Jesus is on the cross which is mounted on decorated wooden steps. There’s a ladder, hammer, and what looks like a jug (possibly for the vinegar?), all in an old wine bottle. I was at Sevenhill last weekend and very keen to re-acquaint myself with this object. However, it has become another victim of Covid-19 – the museum has had to be dismantled for now to allow for extra tasting tables and social distancing. Hopefully, it will be reinstated in years to come, but for now, I just had to buy some wine instead.

References

Kinmonth, C. 2020 Irish Country Furniture and Furnishings 1700-2000. Cork: Cork University Press.

May Day flowers

Today is May Day. For many people it’s International Workers’ Day, but it’s also the ancient spring festival of Bealtaine, celebrated during my childhood as the beginning of an entire month dedicated to Mary. And even though I’m living in the southern hemisphere these days, and we’re in the second month of autumn, old habits die hard.

In primary school, we used to have May altars in the classroom and in our houses. My great friend Steph remembers her particular school tradition:

We had a procession into the convent garden and each class put a bunch of flowers at the foot of the statue. Everyone brought in flowers, which were put together to make a bunch. One person from each class was the chosen one to lay the bunch at the feet of Mary. I loved it! My friend Finny and I would go down the bog at the back of our house picking wild irises early in the morning. And we sang Bring Flowers of the Rarest, Queen of the May to our heart’s content. (Stephanie Burton 1 May 2021)

My mum was never overly enamoured with May altars so I had to have mine in my bedroom. I had a statue of the Virgin Mary and I surrounded her with tiny vases of flowers filched from my dad’s garden or from the fields around our house.

These days, I don’t have a May altar but I do put flowers on the threshold early on May Day. This morning, I was the first one up in the house, and went barefoot to the back garden at dawn where I cut some petunias and sprigs of jasmine leaf. I don’t think being barefoot is mandatory, but it was such a beautiful morning it seemed a shame not to. Then I placed the flowers carefully on the threshold for love, luck and good health for all in the house. According to legend, witches and fairies are unusually active at this time of the year (Evans 1957:272). Thankfully, they can’t cross a threshold strewn with flowers, so that’s an added safety measure put in place!

Flowers are a common custom recorded in Irish folklore for the first day of May, described by Kevin Danaher:

Perhaps the commonest custom of all, examples of which might be cited for every county in Ireland, was the picking and bringing home of fresh flowers… Usually these were gathered before dusk on May Eve by the children, although in many places the tradition lingers that they should be picked before dawn on May Day. The children usually made ‘posies’ of the flowers, small bouquets, which they hung up in the house or laid on the doorsteps or window-sills or hung over the door. (Danaher 1972:88)

References

Danaher, K. 1972 The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs. Cork: The Mercier Press.

Evans, E.E. 1957 Irish Folk Ways. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Leprechauns in Adelaide for Saint Patrick’s Day 2021

I had started writing something completely different in preparation for 17 March and then I found the object pictured below. Isn’t it perfect? It was in an op shop, in a dusty plastic bag. It cost me $3.99. Which may have been over-investment in what is essentially some plastic tat and a cheap golden candle. But leprechauns! There is no point of origin marked anywhere – Ireland, China, Germany, it’s a mystery. These leprechauns materialised all by themselves in Adelaide and I have to say that when I washed off the dust they were even better than I expected. First of all, there are four of them. Usually, the leprechaun is a solitary creature. Secondly, two of them are using the candle to pole dance; this is not something I have ever encountered before, it’s certainly not a tradition I’ve come across in my research. And thirdly, the cauldron of gold and shamrocks of green are quite perfectly formed and heavy for their size. Class!

Four leprechauns, a pot of gold, some green shamrocks and a candle.

The rest of the family is not so enamoured. ‘Donate them back’, I was told. ‘They’re embarrassing.’ ‘They have no place in a modern Irish Australian home.’ A compromise was reached and they are now confined to the study, banned from appearing anywhere else in the house. ‘And you have to donate them back soon.’ ‘Of course’, I lie. Because by now I’m quite fond of them.

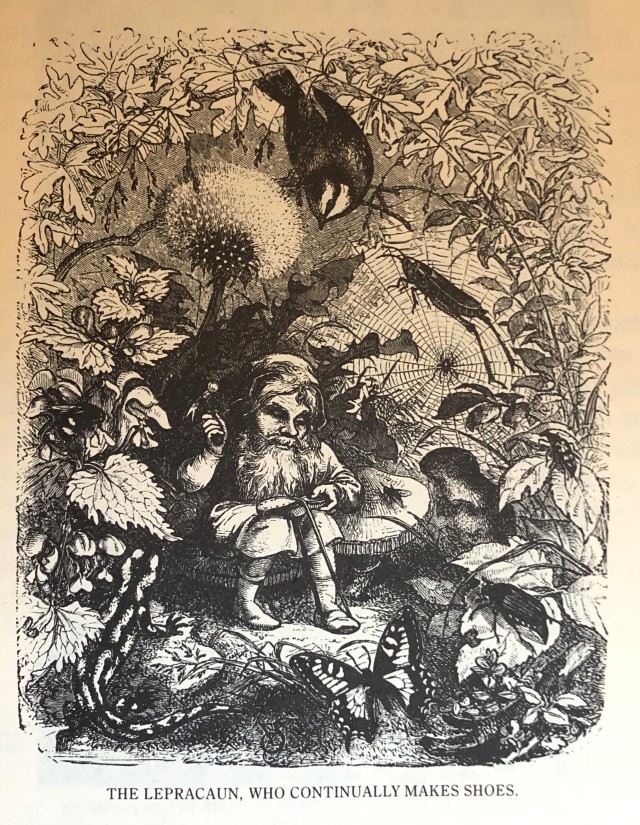

The leprechaun is probably the most widely known Irish mythological creature. Traditionally, he is the fairy shoemaker, banker and guard of the fairy treasure. In fact, his very name comes from one of his occupations – leprechaun, according to Douglas Hyde (first President of Ireland and scholar) via W.B. Yeats (poet and collector of Irish legends), comes from the Irish leith bróg, the one-shoemaker, as the leprechaun is usually spotted working on a single shoe. If you encounter a leprechaun and keep a hold of him, he is obliged to show you the location of his gold hoard. Which, when you think about it, doesn’t seem like quite the right action by us mortals. If he’s essentially the fairy banker, the pot of gold belongs to the fairies or good people; it’s not ours to steal. And I for one wouldn’t want to get on their bad side. Leave well alone I say. If you meet a leprechaun while out and about, exchange good wishes, mention the weather, wish each other good health and safety in these Covid times, and go about your business.

Drawing of a leprechaun at work on a shoe (Yeats, W.B. (1986 [1888]:81).

I think these four leprechauns who have taken up residence in our house may stay for a while. And then they’ll probably move on of their own accord. When they’re quite ready.

In the meantime, I’m sure they’ll join with me in wishing everyone a happy, safe and socially distanced Saint Patrick’s Day in 2021.

Further reading:

White, Carolyn 2008 A History of Irish Fairies. Cork: Mercier Press.

Yeats, W.B. (ed.) 1986 [1888] Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry. New York: Avanel Books.

Culchie Day in the big city

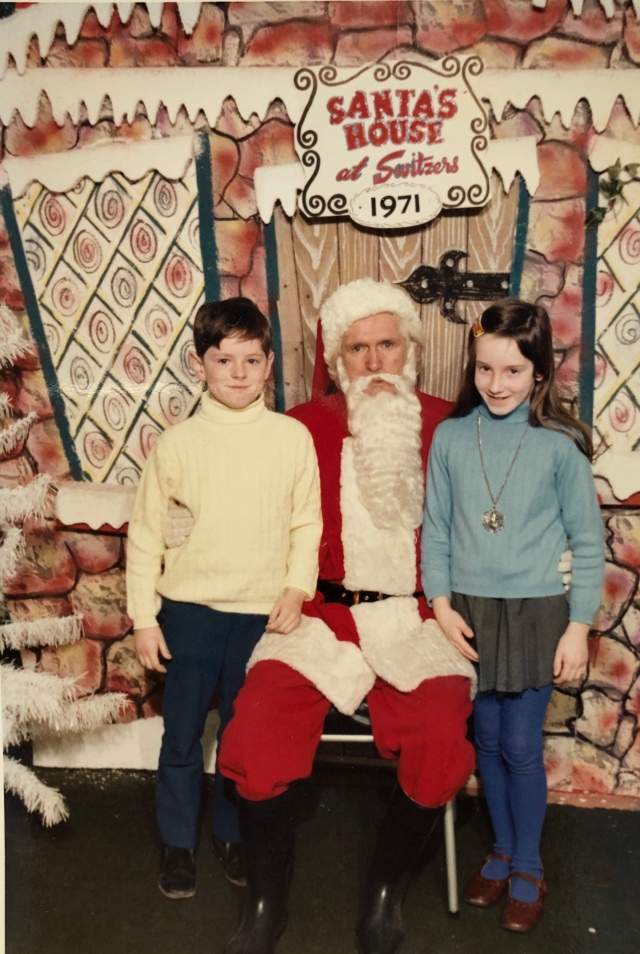

Today is 8 December. It’s a holy day of obligation, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, and when I was a child it was a day off school. Traditionally, this was the day that the country people went to Dublin to do their Christmas shopping, and known by Dubliners for this reason as Culchie Christmas Shopping Day. We never did this – my dad couldn’t abide the thought of those Dublin jackeens laughing at the culchies up from the country on the 8th. We went the weekend before to see the lights in Henry Street, the women on Moore Street crying ‘Last of the cheeky charlies’, the toys in Hector Grey’s and Roches Stores. And then the walk up and over the Ha’penny Bridge, past College Green to Grafton Street and Switzers where we were able to tell Santy what we wanted and gaze at the Christmas windows in wonder.

Santa at Switzers, 1971

In defence of Dublin, the Santa Claus at Switzers was a lot less scary than his alter ego down the country.

Santa in Longford, c.1966

Extensive research (a quick look in Google) finds that Culchie Day is no longer such a big event. Online shopping and the American Black Friday sales mean that 8 December is less relevant. But for many people, it is still the day to start Christmas and put up the decorations. And in this pandemic year, when many of us are physically further apart from our families than ever before, it might be even more important to celebrate family and friendship and the anticipation of an upcoming feast. Happy Christmas on Culchie Day!

Posted in Around the world, Folk traditions, Ireland, Irishness | Tagged Christmas, Culchie Christmas Shopping Day, Culchie Day, Dublin, jackeens, Santa Claus, Santy, Switzers |