Pertussis: Practice Essentials, Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Practice Essentials

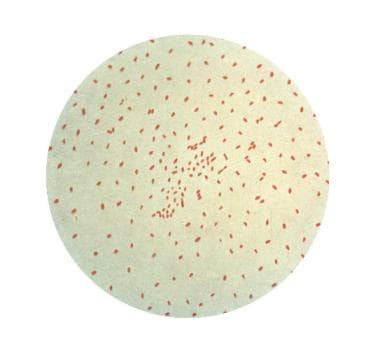

Pertussis (whooping cough) is a respiratory tract infection characterized by a paroxysmal cough. The most common causative organism is Bordetella pertussis (see the image below), though Bordetella parapertussis also has been associated with this condition in humans. Pertussis remains a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in infants younger than 2 years.

A photomicrograph of the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, using Gram stain technique.

Signs and symptoms

Pertussis is a 6-week disease divided into catarrhal, paroxysmal, and convalescent stages, each lasting 1-2 weeks.

Stage 1 – Catarrhal phase

- Nasal congestion

- Rhinorrhea

- Sneezing

- Low-grade fever

- Tearing

- Conjunctival suffusion

Stage 2 – Paroxysmal phase

- Paroxysms of intense coughing lasting up to several minutes, occasionally followed by a loud whoop

- Posttussive vomiting and turning red with coughing

Stage 3 – Convalescent stage

- Chronic cough, which may last for weeks

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of pertussis is made by isolation of B pertussis in culture. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test also can be performed.

- The culture specimen should be obtained during the first 2 weeks of cough by using deep nasopharyngeal aspiration

- For PCR testing, nasopharyngeal specimens should be taken at 0-3 weeks following cough onset

- The CDC recommends a combination of culture and PCR assay if a patient has a cough lasting longer than 3 weeks

- Early serial monitoring of white blood cell (WBC) counts is warranted

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Goals of treatment

- Limit the number of paroxysms

- Observe the severity of cough and provide assistance when necessary

- Maximize nutrition, rest, and recovery

Pharmacologic therapy

- Antimicrobial agents and antibiotics can hasten the eradication of B pertussis and help prevent spread

- Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin are the preferred agents for patients aged 1 month or older

Immunization

Prevention through immunization remains the best defense in the fight against pertussis. CDC recommendations for vaccination are as follows:

- DTaP vaccine: Recommended at the ages of 2, 4, 6, and 15-18 months and at age 4-6 years; it is not recommended for children aged 7 years or older

- Tdap vaccine: Recommended for children aged 7-10 years who are not fully vaccinated; as a single dose for adolescents 11-18 years of age; for any adult 19 years of age or older; and for pregnant woman regardless of vaccination history, including repeat vaccinations in subsequent pregnancies [1, 2]

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Pertussis, commonly known as whooping cough, is a respiratory tract infection characterized by a paroxysmal cough. It first was identified in the 16th century. In 1906, Bordet isolated the most common causative organism, Bordetella pertussis. Bordetella parapertussis also has been associated with whooping cough in humans. (See Etiology and Pathophysiology.)

A photomicrograph of the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, using Gram stain technique.

In the prevaccination era, pertussis (ie, whooping cough) was a leading cause of infant death. As a result of vaccination, however, the number of cases reported decreased by more than 99% from the 1930s to the 1980s. Nonetheless, because of many local outbreaks, the number of cases reported in the United States increased by more than 2300% between 1976 and 2005. (See Epidemiology.) [3]

The disease still is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in infants younger than 2 years. Pertussis should be included in the differential diagnosis of protracted cough with cyanosis or vomiting, persistent rhinorrhea, and marked lymphocytosis. (See Prognosis, DDx, Presentation, and Workup.) [4]

Complications of pertussis can include the following (see Prognosis, Treatment, and Medication):

- Hypoxic encephalopathy

- Tuberculosis activation

- Hernia

- Reinduction of paroxysmal coughing with upper respiratory infections

- Seizures

- Cerebral hemorrhage

- Coma and death

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Humans are the sole reservoir for B pertussis and B parapertussis. B pertussis, a gram-negative pleomorphic bacillus, is the main causative organism for pertussis. (B parapertussis is less common than B pertussis and produces a clinical illness that is similar to, but milder than, that produced by B pertussis.) B pertussis spreads via aerosolized droplets produced by the cough of infected individuals, attaching to and damaging ciliated respiratory epithelium. B pertussis also multiplies on the respiratory epithelium, starting in the nasopharynx and ending primarily in the bronchi and bronchioles. [5]

Pertussis is highly contagious, developing in approximately 80-90% of susceptible individuals who are exposed to it. Most cases occur in the late summer and early fall.

A mucopurulent sanguineous exudate forms in the respiratory tract. This exudate compromises the small airways (especially those of infants) and predisposes the affected individual to atelectasis, cough, cyanosis, and pneumonia. The lung parenchyma and bloodstream are not invaded; therefore, blood culture results are negative.

Transmission of pertussis can occur through direct face-to-face contact, through sharing of a confined space, or through contact with oral, nasal, or respiratory secretions from an infected source. In a study of pertussis in 4 US states, out of 264 infants with the disease, the infant’s mother was the source of pertussis in 32% of cases, and another family member was the source in 43% of cases. [6]

Although mothers historically have been the most common source of transmission of pertussis to their infant, data from a study found that the most common source of transmission to infants is through their siblings. [7, 8]

Young infants, especially those born prematurely, and patients with underlying cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, or neurologic disease are at high risk of contracting the disease and for complications.

Risk factors for pertussis include the following:

- Nonvaccination in children

- Contact with an infected person

- Epidemic exposure

- Pregnancy

An Australian study of adult risk factors for pertussis not only found that persons aged 65 years or older were more likely than those aged 45-64 years to be hospitalized for pertussis, but that adults with obesity or preexisting asthma had a greater likelihood of being diagnosed with pertussis. (The investigators did not see a link between the pertussis incidence and age.) The population-based, prospective, cohort study involved 263,094 adults aged 45-64 years. [9]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

Since the early 1980s, pertussis incidence has cyclically increased, with peaks occurring every 2-5 years. [10] Most cases occur between June and September. Neither acquisition of the disease nor vaccination provides complete or lifelong immunity. Protection against typical disease wanes 3-5 years after vaccination and is not measurable after 12 years. [11, 12, 13]

The rate of pertussis peaked in the 1930s, with 265,269 cases and 7518 deaths reported in the United States. This rate decreased to a low of 1010 cases in the United States, with 4 deaths, in 1976. Starting in the 1980s, however, the reported incidence of US pertussis cases dramatically increased across all age groups. Although the largest increase in pertussis cases has been among adolescents and adults, the annual reported incidence has been highest among infants younger than 1 year. [14]

In 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the US pertussis rate reached 27,550 cases (the highest number since 1959), with 27 related deaths. [15, 16]

In 2011, according to preliminary statistics from the CDC, adolescents (ages 11-19 years) and adults together accounted for 47% of pertussis cases, whereas children aged 7-10 years accounted for 18% of cases. [16, 17]

According to the CDC, during the first half of 2012, most states had reported either increased pertussis activity or outbreaks of the disease. By July 5 of that year, 37 states had reported increases in pertussis cases over those reported during the same period in 2011.

For example, as listed by the CDC and the states’ health departments, the number of reported cases in Washington State (where a pertussis epidemic was declared), Minnesota, and Wisconsin in 2012 were as follows [16] :

- Washington State - 2012: 3400 cases reported through Aug 4; 2011: 287 cases reported through Aug 4

- Minnesota - 2012: 2039 cases reported as of Aug 2; 2011 (entire year): 661 cases reported

- Wisconsin - 2012: 3496 confirmed or probable cases reported through July 31, 2012; 2011 (entire year): 1192 confirmed or probable cases reported

The CDC listed a provisional national figure of 17,000 pertussis cases between Jan 1 and July 21, 2012, including 9 pertussis-related deaths. The reasons that pertussis cases peak in some years is not completely understood, according to the CDC. [16]

The CDC has estimated that 5-10% of all cases of pertussis are recognized and reported. Pertussis remains the most commonly reported vaccine-preventable disease in the United States in children younger than 5 years. In studies, 12-32% of adults with prolonged (1-4 wk) cough have been found to have pertussis.

Between January 1, 2014 and June 10, 2014 California's public health department reported 3,458 cases of pertussis. The department declared the outbreak to have reached epidemic proportions, with 800 cases reported in the span of just 2 weeks. [18] A study that examined a similar outbreak in California in 2010 determined that nonmedical vaccine exemptions played a role. [19]

Nationally, the CDC stated that the 4,838 cases of pertussis reported from January 1, 2014 to April 14, 2014 represented a 24% increase over the same period in 2013. [20]

The CDC reports that during January 1–November 26, 2014, a total of 9,935 cases of pertussis with onset in 2014 were reported in California. Severe and fatal disease occurs almost exclusively in infants who are too young to be vaccinated against pertussis. Therefore, pregnant women are encouraged to receive tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) during the third trimester of each pregnancy to provide placental transfer of maternal antibodies to the infant. [21, 22]

International occurrence

The annual worldwide incidence of pertussis is estimated to be 48.5 million cases, with a mortality rate of nearly 295,000 deaths per year. [23] The case-fatality rate among infants in low-income countries may be as high as 4%. [24]

In England, the percentage of people vaccinated for pertussis over the last 4 decades has decreased to less than 30%. This decline has resulted in thousands of recently reported cases of the disease, with the incidence rate approaching that of the prevaccination era. Similar epidemic outbreaks recently have occurred in Sweden, Canada, and Germany. Nearly 300,000 deaths from pertussis are thought to have occurred in Africa over the last decade.

Race- and sex-related demographics

With regard to race, the CDC reported that among individuals with pertussis between 2001 and 2003, 90% were white, 7% were black, 1% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1% were American Indian/Alaska Native, and 1% were identified as “other race”. From 2001-2003, females accounted for 54% of pertussis cases in the United States. [25]

Age-related demographics

From 2001-2003, of patients with pertussis, 23% were younger than 1 year, 12% were aged 1-4 years, 9% were aged 5-9 years, 33% were aged 10-19 years, and 23% were older than 20 years. [26, 25]

Because of the lack of maternal immunity transfer, 10-15% of all cases of pertussis occur in infants younger than 6 months; more than 90% of all deaths occur in this same age group. However, the growing majority of cases now are in persons aged 10 years and older, which has led to increased booster recommendations.

Prognosis

Prognosis for full recovery from pertussis is excellent in children older than 3 months of age. In those younger than 3 months, the mortality is 1-3%.

Complications of pertussis in older infants and children usually are minimal, and most patients make a gradual, but full, recovery with supportive care and antibiotics. Minor complications during the illness include epistaxis, nausea and vomiting, subconjunctival hemorrhages, and ulcers of the frenulum.

Patients with certain comorbid conditions, however, have a higher risk for morbidity and mortality and should be evaluated on an individual basis.

In addition, compared with older children and adults, infants younger than 6 months with pertussis are more likely to have severe disease, to develop complications, and to require hospitalization. From 2001-2003, 69% of infants younger than 6 months with pertussis required hospitalization. [14]

Reported deaths due to pertussis in young infants have increased substantially since the late 20th century. Between 2004 and 2008, out of a total 111 pertussis-related deaths reported to the CDC, 92 (83%) were in infants aged 3 months or less. [27, 28, 15]

Pneumonia, either from Bordetella pertussis infection or from secondary infection with other pathogens, is a relatively common complication, occurring in approximately 13% of infants with pertussis. [26]

Central nervous system (CNS) complications, such as seizures (1-2% of infants) and encephalopathy, are less common and are thought to result from severe, paroxysm-induced cerebral hypoxia and apnea; metabolic disturbances such as hypoglycemia; and small intracranial hemorrhages. Failure to thrive is another possible complication of pertussis.

Leukocytosis, particularly with white blood cell (WBC) counts of more than 100,000, has been associated with fatalities from pertussis. Another study showed that WBC counts of more than 55,000 and pertussis complicated by pneumonia were independent predictors of fatal outcome in a multivariate model.

Infants born prematurely and patients with underlying cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular, or neurologic disease are at high risk for complications of pertussis (eg, pneumonia, seizures, encephalopathy, death).

Older children, adolescents, and adults often have mild or atypical illness. Approximately one half of adolescents with pertussis cough for 10 weeks or longer. Complications among adolescents and adults include syncope, sleep disturbance, incontinence, rib fractures, and pneumonia. Seizures occur in 0.3-0.6% of adults.

Control measures should be implemented immediately when 1 or more cases of pertussis are recognized in healthcare settings such as a hospital, institution, or outpatient clinic. Confirmed and suspected cases should be reported to the local health departments, and their involvement in control measures should be sought.

Patient Education

When a diagnosis of pertussis is made, patient and parent education and individualized supportive treatment are the best options. All parents should receive information regarding the infectious and contagious potential of pertussis, as well as the risks derived from the vaccine.

Prevention of pertussis involves the use of vaccine approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and standard infection control precautions.

For patient education information, see the Children's Health Center, as well as Whooping Cough (Pertussis) and Immunization Schedule, Children.

- Robinson CL, Romero JR, Kempe A, Pellegrini C, Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Child/Adolescent Immunization Work Group. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Feb 10. 66 (5):134-135. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kim DK, Riley LE, Harriman KH, Hunter P, Bridges CB. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Feb 10. 66 (5):136-138. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Outbreaks of respiratory illness mistakenly attributed to pertussis--New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Tennessee, 2004-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007 Aug 24. 56(33):837-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marconi GP, Ross LA, Nager AL. An upsurge in pertussis: epidemiology and trends. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012 Mar. 28(3):215-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Walsh PF, Kimmel L, Feola M, Tran T, Lim C, De Salvia L, et al. Prevalence of Bordetella pertussis and Bordetella parapertussis in infants presenting to the emergency department with bronchiolitis. J Emerg Med. 2011 Mar. 40(3):256-61. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Bisgard KM, Pascual FB, Ehresmann KR, Miller CA, Cianfrini C, Jennings CE, et al. Infant pertussis: who was the source?. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004 Nov. 23(11):985-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Skoff TH, Kenyon C, Cocoros N, Liko J, Miller L, Kudish K, et al. Sources of Infant Pertussis Infection in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015 Sep 7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Skwarecki B. Infants More Likely to Contract Pertussis From Siblings. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/850781\. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/850781. September 10, 2015; Accessed: September 14, 2015.

- Liu BC, McIntyre P, Kaldor JM, Quinn H, Ridda I, Banks E. Pertussis in older adults: prospective study of risk factors and morbidity. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Jul 26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cherry JD, Heininger U. Pertussis and other Bordetella Infections. In: Feigin RD, Demmler GJ, Cherry JD, Kaplan SL. Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Co.; 2004:1588-1608:

- Notes from the field : use of tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in an Emergency Department - Arizona, 2009-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jan 27. 61(3):55-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Winter K, Harriman K, Zipprich J, Schechter R, Talarico J, Watt J, et al. California Pertussis Epidemic, 2010. J Pediatr. 2012 Jul 20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pertussis epidemic - washington, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012 Jul 20. 61:517-22. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pertussis--United States, 2001-2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005 Dec 23. 54(50):1283-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control. Pertussis. In: Atkinson W, Wolfe S, Hamborsky. J. Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. 12th ed. Washington DC: Public Health Foundation; 2012:215-231:[Full Text].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (Whooping Cough): Outbreaks. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks.html. Accessed: Aug 9, 2012.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (Whooping Cough): Surveillance and Reporting. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/surv-reporting.html. Accessed: Aug 10, 2012.

- Christensen J. California declares whooping cough epidemic. CNN.com. Available at https://www.cnn.com/2014/06/13/health/whooping-cough-california/. Accessed: June 17, 2014.

- Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J, Winter K, Harriman K, Salmon DA. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics. 2013 Oct. 132(4):624-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- CDC. Pertussis Outbreak Trends. CDC.gov. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/outbreaks/trends.html. Accessed: June 17, 2014.

- Barclay L. Pertussis Cases Near 10,000 in California This Year. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/835898. Accessed: December 5, 2014.

- Winter K, Glaser C, Watt J, et al. Pertussis Epidemic — California, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014. 63:1129-1132. [Full Text].

- Bettiol S, Thompson MJ, Roberts NW, Perera R, Heneghan CJ, Harnden A. Symptomatic treatment of the cough in whooping cough. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jan 20. CD003257. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Nitsch-Osuch A, Kuchar E, Modrzejewska G, Pirogowicz I, Zycinska K, Wardyn K. Epidemiology of Pertussis in an Urban Region of Poland: Time for a Booster for Adolescents and Adults. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013. 755:203-212. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis--United States, 2001-2003 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Dec 23, 2005;54(50):1283-6. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5450a3.htm. Accessed: Aug 9, 2012.

- Mattoo S, Cherry JD. Molecular pathogenesis, epidemiology, and clinical manifestations of respiratory infections due to Bordetella pertussis and other Bordetella subspecies. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005 Apr. 18(2):326-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Bisgard K. Background. Guidelines for the Control of Pertussis Outbreaks. 2000;1-1-1-11:[Full Text].

- Vitek CR, Pascual FB, Baughman AL, Murphy TV. Increase in deaths from pertussis among young infants in the United States in the 1990s. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003 Jul. 22(7):628-34. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Guinto-Ocampo H, Bennett JE, Attia MW. Predicting pertussis in infants. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008 Jan. 24(1):16-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Waknine Y. Infant Pertussis: Early White Blood Cell Counts Crucial. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/777732. Accessed: January 23, 2013.

- Murray E, Nieves D, Bradley J, et al. Characteristics of Severe Bordetella pertussis Infection Among Infants Older than 90 Days of Age Admitted to Pediatric Intensive Care Units – Southern California, September 2009–June 2011. J Ped Infect Dis. 2013.

- Edwards K, Decker MD. Pertussis vaccine. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA. Vaccines. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2004:471-528.

- de Greeff SC, Mooi FR, Westerhof A, Verbakel JM, Peeters MF, Heuvelman CJ, et al. Pertussis disease burden in the household: how to protect young infants. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 May 15. 50(10):1339-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] American Academy of Pediatric Committee on Infectious Diseases. Prevention of pertussis among adolescents: recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine. Pediatrics. 2006 Mar. 117(3):965-78. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Additional recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced-content diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap). Pediatrics. 2011 Oct. 128(4):809-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women and persons who have or anticipate having close contact with an infant aged MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Oct 21. 60(41):1424-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McNamara LA, Skoff T, Faulkner A, Miller L, Kudish K, Kenyon C, et al. Reduced Severity of Pertussis in Persons With Age-Appropriate Pertussis Vaccination-United States, 2010-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 1. 65 (5):811-818. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Harding A. Pertussis Vaccine Appears Safe in Pregnancy for Mom, Baby. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/834849. Accessed: November 14, 2014.

- Kharbanda EO, Vazquez-Benitez G, Lipkind HS, Klein NP, Cheetham TC, Naleway A, et al. Evaluation of the association of maternal pertussis vaccination with obstetric events and birth outcomes. JAMA. 2014 Nov 12. 312(18):1897-904. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Skoff TH, Blain AE, Watt J, Scherzinger K, McMahon M, Zansky SM, et al. Impact of the US Maternal Tetanus, Diphtheria, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccination Program on Preventing Pertussis in Infants Clin Infect Dis. 2017 Sep 28. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kent A, Ladhani SN, Andrews NJ, et al. Pertussis Antibody Concentrations in Infants Born Prematurely to Mothers Vaccinated in Pregnancy. Pediatrics. Online: June 2016:

- Pregnant Women and Tdap Vaccination, Internet Panel Survey, United States, April 2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/tdap-report-2016.html. September 19, 2016; Accessed: October 20, 2017.

- Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule--United States, 2014. Pediatrics. 2014 Feb. 133(2):357-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Pickering LK, ed. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

- Zhang L, Prietsch SO, Axelsson I, Halperin SA. Acellular vaccines for preventing whooping cough in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jan 19. CD001478. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Glanz JM, McClure DL, Magid DJ, Daley MF, France EK, Salmon DA, et al. Parental refusal of pertussis vaccination is associated with an increased risk of pertussis infection in children. Pediatrics. 2009 Jun. 123(6):1446-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Immunization Schedules. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/index.html. Accessed: Aug 9, 2012.

- Brown T. Pertussis vaccines: whole-cell more durable than acellular. Medscape Medical News. May 22, 2013. [Full Text].

- Klein NP, Bartlett J, Fireman B, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Baxter R. Comparative Effectiveness of Acellular Versus Whole-Cell Pertussis Vaccines in Teenagers. Pediatrics. 2013 May 20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- New S, Winter K, Boyte R, Harriman K, Gutman A, Christiansen A, et al. Barriers to Receipt of Prenatal Tetanus Toxoid, Reduced Diphtheria Toxoid, and Acellular Pertussis Vaccine Among Mothers of Infants Aged MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Sep 28. 67 (38):1068-1071. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pitisuttithum P, Chokephaibulkit K, Sirivichayakul C, et al. Antibody persistence after vaccination of adolescents with monovalent and combined acellular pertussis vaccines containing genetically inactivated pertussis toxin: a phase 2/3 randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018 Sep 25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Updated recommendations for use of tetanus toxoid, reduced diphtheria toxoid, and acellular pertussis vaccine (Tdap) in pregnant women--Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013 Feb 22. 62 (7):131-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- WHO. Leading health agencies outline updated terminology for pathogens that transmit through the air. World Health Organization. Available at https://www.who.int/news/item/18-04-2024-leading-health-agencies-outline-updated-terminology-for-pathogens-that-transmit-through-the-air. April 18,2024; Accessed: April 25, 2024.

- Wodi AP, Issa AN, Moser CA, Cineas S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older — United States, 2025. MMWR. January 16, 2025. 74(2):30-33. [Full Text].

- Issa AN, Wodi AP, Moser DA, Cineas S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger — United States, 2025. MMWR. January 16, 2025. 74(2):26-29. [Full Text].

- A photomicrograph of the bacterium Bordetella pertussis, using Gram stain technique.

Author

Coauthor(s)

Bryon K McNeil, MD Medical Director, Bioterrorism and Emergency Preparedness, Clinical Assistant Professor, Departments of Internal Medicine and Emergency Medicine, Via Christ Regional Medical Center

Bryon K McNeil, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, Pennsylvania Medical Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Russell W Steele, MD Clinical Professor, Tulane University School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Ochsner Clinic Foundation

Russell W Steele, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Immunologists, American Pediatric Society, American Society for Microbiology, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Louisiana State Medical Society, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Society for Pediatric Research, Southern Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

Hazel Guinto-Ocampo, MD Consulting Staff, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Division of Emergency Medicine, Nemours Children's Clinic, AI duPont Hospital for Children

Hazel Guinto-Ocampo, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Emergency Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Gary J Noel, MD Professor, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College; Attending Pediatrician, New York-Presbyterian Hospital

Gary J Noel, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mark R Schleiss, MD American Legion Chair of Pediatrics, Professor of Pediatrics, Division Director, Division of Infectious Diseases and Immunology, Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota Medical School

Mark R Schleiss, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Pediatric Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and Society for Pediatric Research

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Garry Wilkes MBBS, FACEM, Director of Emergency Medicine, Calvary Hospital, Canberra, ACT; Adjunct Associate Professor, Edith Cowan University; Clinical Associate Professor, Rural Clinical School, University of Western Australia

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mary L Windle, PharmD Adjunct Associate Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Grace M Young, MD Associate Professor, Department of Pediatrics, University of Maryland Medical Center

Grace M Young, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Pediatrics and American College of Emergency Physicians

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.