Bell Palsy: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy (original) (raw)

Overview

Practice Essentials

Bell palsy, also termed idiopathic facial paralysis (IFP), is the most common cause of unilateral facial paralysis. It is one of the most common neurologic disorders of the cranial nerves (see the image below). In the great majority of cases, Bell palsy gradually resolves over time, and its cause is unknown.

Signs and symptoms of Bell palsy

Signs and symptoms of Bell palsy include the following:

- Acute onset of unilateral upper and lower facial paralysis (over a 48-hr period)

- Posterior auricular pain

- Decreased tearing

- Hyperacusis

- Taste disturbances

- Otalgia

- Weakness of the facial muscles

- Poor eyelid closure

- Aching of the ear or mastoid

- Tingling or numbness of the cheek/mouth

- Epiphora

- Ocular pain

- Blurred vision

- Flattening of forehead and nasolabial fold on the side affected by palsy

- When patient raises eyebrows, palsy-affected side of forehead remains flat

- When patient smiles, face becomes distorted and lateralizes to side opposite the palsy

See Clinical Presentation for more specific information on the signs and symptoms of Bell palsy.

Diagnosis of Bell Palsy

Examination for Bell palsy includes the following:

- Otologic examination: Pneumatic otoscopy and tuning fork examination, particularly if evidence of acute or chronic otitis media

- Ocular examination: Patient often unable to completely close eye on affected side

- Oral examination: Taste and salivation often affected

- Neurologic examination: All cranial nerves, sensory and motor testing, cerebellar testing

Grading

The grading system developed by House and Brackmann categorizes Bell palsy on a scale of I to VI, [1, 2, 3] as follows:

Grade I: normal facial function

Grade II: mild dysfunction

Grade III: moderate dysfunction

Grade IV: moderately severe dysfunction

Grade V: severe dysfunction

Grade VI: total paralysis

See Clinical Presentation for more specific information on patient history and physical examination for Bell palsy.

Testing

Although there are no specific diagnostic tests for Bell palsy, the following may be useful for identifying or excluding other disorders:

- Rapid plasma reagin and/or venereal disease research laboratory test or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption test

- HIV screening by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and/or Western blot

- Complete blood count

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Thyroid function

- Serum glucose

- CSF analysis

- Blood glucose

- Hemoglobin A1c

- Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody levels

- Salivary flow

- Schirmer blotting test

- Nerve excitability test

- Computed tomography

- Magnetic resonance imaging

See Workup for more specific information on testing and imaging modalities for Bell palsy.

Management of Bell Palsy

Goals of treatment: (1) improve facial nerve (seventh cranial nerve) function; (2) reduce neuronal damage; (3) prevent complications from corneal exposure

Treatment includes the following:

- Corticosteroid therapy (prednisone) [4, 5]

- Antiviral agents [4, 6]

- Eye care: Topical ocular lubrication is usually sufficient to prevent corneal drying, abrasion, and ulcers [7]

Surgical options

Surgical treatment options include the following:

- Facial nerve decompression

- Subocularis oculi fat lift

- Implantable devices (eg, gold weights) placed into the eyelid

- Tarsorrhaphy [2]

- Transposition of the temporalis muscle

- Facial nerve grafting

- Direct brow lift

See Treatment and Medication for more specific information regarding pharmacologic and other therapies for Bell palsy.

Impact of COVID-19 Infection and SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine

Viruses and vaccinations have been identified as risk factors for development of Bell palsy. Idiopathic facial paralysis (IFP) has been reported in association with COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 as well as the currently available vaccinations. The specific risk associated with COVID-19, SAR-CoV-2, and the SARS-CoV-2 vaccines has not yet been been determined. [8]

Background

Bell palsy, more appropriately termed idiopathic facial paralysis (IFP), is the most common cause of unilateral facial paralysis. Bell palsy is an acute, unilateral, peripheral, lower-motor-neuron facial nerve paralysis that gradually resolves over time in 80–90% of cases.

Controversy surrounds the etiology and treatment of Bell palsy. The cause of Bell palsy remains unknown, though the disorder appears to be a polyneuritis with possible viral, inflammatory, autoimmune, and ischemic etiologies. Increasing evidence implicates herpes simplex type I and herpes zoster virus reactivation from cranial-nerve ganglia. [9] (See Etiology.)

Bell palsy is one of the most common neurologic disorders affecting the cranial nerves, and it is the most common cause of facial paralysis worldwide. It is thought to account for approximately 60–75% of cases of acute unilateral facial paralysis. Bell palsy is more common in adults, in people with diabetes, and in pregnant women. (See Epidemiology.)

The widespread prevalence of the new coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and associated virus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to some reported cases of IFP. In addition, there have been some reports of IFP associated with the vaccine trials. A study by Ozonoff et al found 7 cases of Bell's palsy among nearly 40,000 vaccine arm participants. There was only 1 case of Bell's palsy among placebo arm participants. This estimated rate ratio of approximately 7:0 suggests vaccination might be associated with Bell's palsy (p=0·07). The cases of Bell palsy associated with COVID-19 and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, as reported, are not of increased severity and respond to current treatment protocols. [10, 8]

Anatomy

In 1550, Fallopius noted the narrow foramen in the temporal bone through which a part of the seventh cranial nerve (facial nerve) passes; this feature is now sometimes called the fallopian canal or the facial canal. In 1828, Charles Bell made the distinction between the fifth and seventh cranial nerves; he noted that the seventh nerve was involved mainly in the motor function of the face and that the fifth nerve primarily conducted sensation from the face.

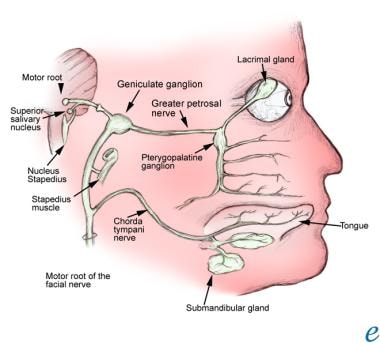

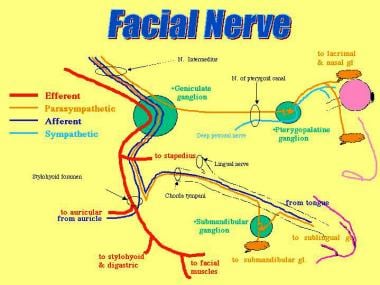

The facial nerve contains parasympathetic fibers to the nose, palate, and lacrimal glands. Its course is tortuous, both centrally and peripherally. The facial nerve travels a 30-mm intraosseous course through the internal auditory canal (with the eighth cranial nerve) and through the internal fallopian canal in the petrous temporal bone. This bony confinement limits the amount that the nerve can swell before it becomes compressed.

The nucleus of the facial nerve lies within the reticular formation of the pons, adjacent to the fourth ventricle. The facial nerve roots include fibers from the motor, solitary, and salivatory nuclei. The preganglionic parasympathetic fibers that originate in the salivatory nucleus join the fibers from nucleus solitarius to form the nervus intermedius.

The nervus intermedius is composed of sensory fibers from the tongue, mucosa, and postauricular skin, as well as parasympathetic fibers to the salivary and lacrimal glands. These fibers then synapse with the submandibular ganglion, which has fibers that supply the sublingual and submandibular glands. The fibers from the nervus intermedius also supply the pterygopalatine ganglion, which has parasympathetic fibers that supply the nose, palate, and lacrimal glands.

The fibers of the facial nerve then course around the sixth cranial nerve nucleus and exit the pons at the cerebellopontine angle. The fibers go through the internal auditory canal along with the vestibular portion of the eighth cranial nerve.

The facial nerve passes through the stylomastoid foramen in the skull and terminates into the zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, and cervical branches. These nerves serve the muscles of facial expression, which include the frontalis, orbicularis oculi, orbicularis oris, buccinator, and platysma muscles. Other muscles innervated by the facial nerve include the stapedius, stylohyoid, posterior belly of the digastric, occipitalis, and anterior and posterior auricular muscles. All muscles innervated by the facial nerve are derived from the second branchial arch. See the images below.

The facial nerve.

The facial nerve.

Pathophysiology

The precise pathophysiology of Bell palsy remains an area of debate. The facial nerve courses through a portion of the temporal bone commonly referred to as the facial canal. A popular theory proposes that edema and ischemia result in compression of the facial nerve within this bony canal. The cause of the edema and ischemia has not yet been established. This compression has been seen in MRI scans with facial nerve enhancement. [11]

The first portion of the facial canal, the labyrinthine segment, is the narrowest; the meatal foramen in this segment has a diameter of only about 0.66 mm. This is the location that is thought to be the most common site of compression of the facial nerve in Bell palsy. Given the tight confines of the facial canal, it seems logical that inflammatory, demyelinating, ischemic, or compressive processes may impair neural conduction at this site.

Injury to the facial nerve in Bell palsy is peripheral to the nerve’s nucleus. The injury is thought to occur near, or at, the geniculate ganglion. If the lesion is proximal to the geniculate ganglion, the motor paralysis is accompanied by gustatory and autonomic abnormalities. Lesions between the geniculate ganglion and the origin of the chorda tympani produce the same effect, except that they spare lacrimation. If the lesion is at the stylomastoid foramen, it may result in facial paralysis only.

Etiology

Herpes simplex virus

In the past, situations that produced cold exposure (eg, chilly wind, cold air conditioning, or driving with the car window down) were considered to be the only triggers for Bell palsy. Several authors now believe, however, that the herpes simplex virus (HSV) is a common cause of Bell palsy, though a definitive causal relationship of HSV to Bell palsy may be difficult to prove because of the ubiquitous nature of HSV.

The hypothesis that HSV is the etiologic agent in Bell palsy holds that after causing primary infection on the lips (ie, cold sores), the virus travels up the axons of the sensory nerves and resides in the geniculate ganglion. At times of stress, the virus reactivates and causes local damage to the myelin.

This hypothesis was first suggested in 1972 by McCormick. [12] Autopsy studies have since shown HSV in the geniculate ganglion of patients with Bell palsy. Murakami et al performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay testing on the endoneural fluid of the facial nerve in patients who underwent surgery for Bell palsy and found HSV in 11 of 14 cases. [13]

Additional support for a viral etiology was seen when intranasal, inactivated influenza vaccine was strongly linked to the development of Bell palsy. [14, 15] With those cases, however, it is not clear whether another component of the vaccine caused the paresis, which was then accompanied by a reactivation of HSV infection.

Additional causes of Bell palsy

Besides HSV infection, possible etiologies for Bell palsy include other infections (eg, herpes zoster, Lyme disease, syphilis, Epstein-Barr viral infection, cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], mycoplasma); inflammation alone; and microvascular disease (diabetes mellitus and hypertension). Bell palsy has also been known to follow recent upper respiratory infection (URI). [16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21]

Bell palsy may be secondary to viral and/or autoimmune reactions that cause the facial nerve to demyelinate, resulting in unilateral facial paralysis.

A family history of Bell palsy has been reported in approximately 4% of cases. Inheritance in such cases may be autosomal dominant with low penetration; however, which predisposing factors are inherited is unclear. [22] The family history may also be positive for other nerve, nerve root, or plexus disorders (eg, trigeminal neuralgia) in siblings. [23] In addition, there are isolated reports of familial Bell palsy with neurologic deficits, including ophthalmoplegia [24] and essential tremor. [25] A rare form of familial Bell palsy has a predilection for juvenile females. [26]

Because there is a strong environmental predisposition to Bell palsy, due to the common viral etiology, a positive family history may or may not indicate a true genetic etiology.

Epidemiology

In the United States, the annual incidence of Bell palsy is approximately 23 cases per 100,000 persons. [5] Very few cases are observed during the summer months. Internationally, the highest incidence was found in a study in Seckori, Japan, in 1986, and the lowest incidence was found in Sweden in 1971. Most population studies generally show an annual incidence of 15–30 cases per 100,000 population.

Bell palsy is thought to account for approximately 60–75% of cases of acute unilateral facial paralysis, with the right side affected 63% of the time. It can also be recurrent, with a reported recurrence range of 4–14%. [17]

Though bilateral simultaneous Bell palsy can develop, it is rare. It accounts for only 23% of bilateral facial paralysis and has an occurrence rate that is less than 1% of that for unilateral facial nerve palsy. [27, 28] The majority of patients with bilateral facial palsy have Guillain-Barré syndrome, sarcoidosis, Lyme disease, meningitis (neoplastic or infectious), or bilateral neurofibromas (in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2).

Persons with diabetes have a 29% higher risk of being affected by Bell palsy than do persons without diabetes. Thus, measuring blood glucose levels at the time of diagnosis of Bell palsy may detect undiagnosed diabetes. Diabetic patients are 30% more likely than nondiabetic patients to have only partial recovery; recurrence of Bell palsy is also more common among diabetic patients. [29]

Bell palsy is also more common in people who are immunocompromised or in women with preeclampsia. [30]

Sex- and age-related demographics

Bell palsy appears to affect the sexes equally. However, young women aged 10–19 years are more likely to be affected than are men in the same age group. Pregnant women have a 3.3 times higher risk of being affected by Bell palsy than do nonpregnant women; Bell palsy occurs most frequently in the third trimester.

In general, Bell palsy occurs more commonly in adults. A slightly higher predominance is observed in patients older than 65 years (59 cases per 100,000 people), and a lower incidence rate is observed in children younger than 13 years (13 cases per 100,000 people). The lowest incidence is found in persons younger than 10 years, and the highest incidence is in persons aged 60 years or older. Peak ages are between 20 and 40 years. The disease also occurs in elderly persons aged 70–80 years. [31]

Prognosis

The natural course of Bell palsy varies from early complete recovery to substantial nerve injury with permanent sequelae (eg, persistent paralysis and synkinesis). Prognostically, patients fall into 3 groups:

- Group 1 - Complete recovery of facial motor function without sequelae

- Group 2 - Incomplete recovery of facial motor function, but with no cosmetic defects that are apparent to the untrained eye

- Group 3 - Permanent neurologic sequelae that are cosmetically and clinically apparent

Approximately 80–90% of patients with Bell palsy recover without noticeable disfigurement within 6 weeks to 3 months. Use of the Sunnybrook grading scale for facial nerve function at 1 month has been suggested as a means of predicting probability of recovery. [32]

Most patients who suffer from Bell palsy have neurapraxia or local nerve conduction block. These patients are likely to have a prompt and complete recovery of the nerve. Patients with axonotmesis, with disruption of the axons, have a fairly good recovery, but it is usually not complete.

The risk factors thought to be associated with a poor outcome in patients with Bell palsy include (1) age greater than 60 years, (2) complete paralysis, and (3) decreased taste or salivary flow on the side of paralysis (usually 10-25% compared with the patient’s normal side). Other factors thought to be associated with poor outcome include pain in the posterior auricular area and decreased lacrimation.

Patients aged 60 years or older have an approximately 40% chance of complete recovery and have a higher rate of sequelae. Patients younger than 30 years have only a 10–15% chance of less than complete recovery and/or long-term sequelae.

The sooner the recovery, the less likely are the chances that sequelae will develop, as summarized below:

- If some restoration of function is noted within 3 weeks, then the recovery is most likely to be complete

- If the recovery begins between 3 weeks and 2 months, then the ultimate outcome is usually satisfactory

- If the recovery does not begin until 2–4 months from the onset, likelihood of permanent sequelae, including residual paresis and synkinesis, is higher

- If no recovery occurs by 4 months, then the patient is more likely to have sequelae from the disease, which include synkinesis, crocodile tears, and (rarely) hemifacial spasm

Bell palsy recurs in 4–14% of patients, with one source suggesting a recurrence rate of 7%. It may recur on the same or opposite side of the initial palsy. Recurrence usually is associated with a family history of recurrent Bell palsy. Higher recurrence rates among patients were reported in the past; however, many of these patients were found to have an underlying etiology for the recurrence, eliminating the diagnosis of Bell palsy, an idiopathic disease. [33]

Patients with recurrent ipsilateral facial palsy should undergo MRI or high-resolution computed tomography (CT) scanning to rule out a neoplastic or inflammatory (eg, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis) cause of recurrence. Recurrent or bilateral disease should suggest myasthenia gravis.

Sequelae

Most patients with Bell palsy recover without any cosmetically obvious deformities. Approximately 30% of patients, however, experience long-term symptoms following the paralysis, and approximately 5% are left with an unacceptably high degree of sequelae. Bell palsy sequelae include incomplete motor regeneration, incomplete sensory regeneration, and aberrant reinnervation of the facial nerve.

Incomplete motor regeneration

The largest portion of the facial nerve is composed of efferent fibers that stimulate muscles of facial expression. Suboptimal regeneration of this portion results in paresis of all or some of these facial muscles. This manifests as (1) oral incompetence, (2) epiphora (excessive tearing), and (3) nasal obstruction.

Incomplete sensory regeneration

Dysgeusia or ageusia (impairment or loss of taste, respectively) may occur with incomplete regeneration of the chorda tympani. Incomplete regeneration of other afferent branches may result in dysesthesia (impairment of sensation or disagreeable sensation to normal stimuli).

Aberrant reinnervation of the facial nerve

During regeneration and repair of the facial nerve, some neural fibers may take an unusual course and connect to neighboring muscle fibers. This aberrant reconnection produces unusual neurologic pathways. When voluntary movements are initiated, they are accompanied by involuntary movements (eg, eye closure associated with lip pursing or mouth grimacing that occurs during blinking of the eye). The condition in which involuntary movements accompany voluntary movements is termed synkinesis.

Patient Education

To prevent corneal abrasions, patients should be instructed about eye care. They also should be encouraged to do facial muscle exercises using passive range of motion, as well as actively close their eyes and smile. Facial exercises can help Bell palsy patients increase muscle strength and coordination in the face. Some of these include raising the eyebrows and holding them in the raised state for 10–15 seconds, curling and snarling the lips, wrinkling the nose, and tilting the head and stretching the neck, among others.

For patient education information, see the Brain and Nervous System Center, as well as Bell’s Palsy.

- Vrabec JT, Backous DD, Djalilian HR, Gidley PW, Leonetti JP, Marzo SJ, et al. Facial Nerve Grading System 2.0. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Apr. 140(4):445-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Seiff SR, Chang J. Management of ophthalmic complications of facial nerve palsy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992 Jun. 25(3):669-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985 Apr. 93(2):146-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Anderson P. New AAN guideline on Bell’s palsy. Medscape Medical News. November 7, 2012. Accessed November 12, 2012. [Full Text].

- Katusic SK, Beard CM, Wiederholt WC, Bergstralh EJ, Kurland LT. Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell's palsy, Rochester, Minnesota, 1968-1982. Ann Neurol. 1986 Nov. 20(5):622-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R. Evidence-based guideline update: Steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012 Nov 7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell's palsy. BMJ. 2004 Sep 4. 329(7465):553-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Codeluppi L, Venturelli F, Rossi J, et al. Facial palsy during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Brain Behav. 2020 NOV 07. 11:[Full Text].

- Peitersen E. The natural history of Bell's palsy. Am J Otol. 1982 Oct. 4(2):107-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Ozonoff A, Nanishi E, Levy O. Bell's palsy and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis 2021. 2021 Feb 24. [Full Text].

- Seok JI, Lee DK, Kim KJ. The usefulness of clinical findings in localising lesions in Bell's palsy: comparison with MRI. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008 Apr. 79(4):418-20. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- McCormick DP. Herpes-simplex virus as a cause of Bell's palsy. Lancet. 1972 Apr 29. 1(7757):937-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Murakami S, Mizobuchi M, Nakashiro Y, Doi T, Hato N, Yanagihara N. Bell palsy and herpes simplex virus: identification of viral DNA in endoneurial fluid and muscle. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Jan 1. 124(1 Pt 1):27-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Stowe J, Andrews N, Wise L. Bell’s palsy and parenteral inactivated influenza vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2006. 2(3):110-2.

- Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, Bopp M, Chen RT, Linder T, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell's palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med. 2004 Feb 26. 350(9):896-903. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Halperin JJ, Golightly M. Lyme borreliosis in Bell's palsy. Long Island Neuroborreliosis Collaborative Study Group. Neurology. 1992 Jul. 42(7):1268-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Peitersen E. Bell's palsy: the spontaneous course of 2,500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002. 4-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Liu J, Li Y, Yuan X, Lin Z. Bell's palsy may have relations to bacterial infection. Med Hypotheses. 2009 Feb. 72(2):169-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Unlu Z, Aslan A, Ozbakkaloglu B, Tunger O, Surucuoglu S. Serologic examinations of hepatitis, cytomegalovirus, and rubella in patients with Bell's palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2003 Jan. 82(1):28-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Morgan M, Moffat M, Ritchie L, Collacott I, Brown T. Is Bell's palsy a reactivation of varicella zoster virus?. J Infect. 1995 Jan. 30(1):29-36. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kawaguchi K, Inamura H, Abe Y, Koshu H, Takashita E, Muraki Y, et al. Reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 and varicella-zoster virus and therapeutic effects of combination therapy with prednisolone and valacyclovir in patients with Bell's palsy. Laryngoscope. 2007 Jan. 117(1):147-56. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yanagihara N, Yumoto E, Shibahara T. Familial Bell's palsy: analysis of 25 families. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1988 Nov-Dec. 137:8-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hemminki K, Li X, Sundquist K. Familial risks for nerve, nerve root and plexus disorders in siblings based on hospitalisations in Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007 Jan. 61(1):80-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lee AG, Brazis PW, Eggenberger E. Recurrent idiopathic familial facial nerve palsy and ophthalmoplegia. Strabismus. 2001 Sep. 9(3):137-41. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Deng H, Le WD, Hunter CB, Mejia N, Xie WJ, Jankovic J. A family with Parkinson disease, essential tremor, bell palsy, and parkin mutations. Arch Neurol. 2007 Mar. 64(3):421-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Zaidi FH, Gregory-Evans K, Acheson JF, Ferguson V. Familial Bell's palsy in females: a phenotype with a predilection for eyelids and lacrimal gland. Orbit. 2005 Jun. 24(2):121-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim YH, Choi IJ, Kim HM, Ban JH, Cho CH, Ahn JH. Bilateral simultaneous facial nerve palsy: clinical analysis in seven cases. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Apr. 29(3):397-400. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell's Palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 23. 351(13):1323-31. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Adour K, Wingerd J, Doty HE. Prevalence of concurrent diabetes mellitus and idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell's palsy). Diabetes. 1975 May. 24(5):449-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Adour KK, Byl FM, Hilsinger RL Jr, Kahn ZM, Sheldon MI. The true nature of Bell's palsy: analysis of 1,000 consecutive patients. Laryngoscope. 1978 May. 88(5):787-801. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gordon SC. Bell's palsy in children: role of the school nurse in early recognition and referral. J Sch Nurs. 2008 Dec. 24(6):398-406. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marsk E, Bylund N, Jonsson L, Hammarstedt L, Engström M, Hadziosmanovic N, et al. Prediction of nonrecovery in Bell's palsy using Sunnybrook grading. Laryngoscope. 2012 Apr. 122(4):901-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pitts DB, Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr. Recurrent Bell's palsy: analysis of 140 patients. Laryngoscope. 1988 May. 98(5):535-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hashisaki GT. Medical management of Bell's palsy. Compr Ther. 1997 Nov. 23(11):715-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Völter C, Helms J, Weissbrich B, Rieckmann P, Abele-Horn M. Frequent detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in Bell's palsy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2004 Aug. 261(7):400-4. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, Schwartz SR, Drumheller CM, Burkholder R, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell's Palsy Executive Summary. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 Nov. 149(5):656-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Murphy TP. MRI of the facial nerve during paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991 Jan. 104(1):47-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kress BP, Griesbeck F, Efinger K, Solbach T, Gottschalk A, Kornhuber AW, et al. Bell's palsy: what is the prognostic value of measurements of signal intensity increases with contrast enhancement on MRI?. Neuroradiology. 2002 May. 44(5):428-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Burmeister HP, Baltzer PA, Volk GF, Klingner CM, Kraft A, Dietzel M, et al. Evaluation of the early phase of Bell's palsy using 3 T MRI. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2011 Oct. 268(10):1493-500. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- May M, Blumenthal F, Klein SR. Acute Bell's palsy: prognostic value of evoked electromyography, maximal stimulation, and other electrical tests. Am J Otol. 1983 Jul. 5(1):1-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hendrix RA, Melnick W. Auditory brain stem response and audiologic tests in idiopathic facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1983 Dec. 91(6):686-90. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Shanon E, Himelfarb MZ, Zikk D. Measurement of auditory brain stem potentials in Bell's palsy. Laryngoscope. 1985 Feb. 95(2):206-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dyck PJ. Peripheral Neuropathy. 3rd. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1993.

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell's palsy. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 18. 357(16):1598-607. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell's palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Nov. 7(11):993-1000. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: Steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell's palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 Apr 10. 56(7):830-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Teixeira LJ, Valbuza JS, Prado GF. Physical therapy for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Dec 7. CD006283. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Cardoso JR, Teixeira EC, Moreira MD, Fávero FM, Fontes SV, Bulle de Oliveira AS. Effects of exercises on Bell's palsy: systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Otol Neurotol. 2008 Jun. 29(4):557-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chen N, Zhou M, He L, Zhou D, Li N. Acupuncture for Bell's palsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Aug 4. CD002914. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Baugh R, Basura G, Ishii L, Schwartz S, Drumheller C, Burkholder R, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline: Bell’s Palsy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg November 2013 vol. 149 no. 3 suppl S1-S27. [Full Text].

- Adour KK, Wingerd J, Bell DN, Manning JJ, Hurley JP. Prednisone treatment for idiopathic facial paralysis (Bell's palsy). N Engl J Med. 1972 Dec 21. 287(25):1268-72. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004 Oct 18. CD001942. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B, et al. A randomised controlled trial of the use of aciclovir and/or prednisolone for the early treatment of Bell's palsy: the BELLS study. Health Technol Assess. 2009 Oct. 13(47):iii-iv, ix-xi 1-130. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Axelsson S, Berg T, Jonsson L, Engström M, Kanerva M, Pitkäranta A, et al. Prednisolone in Bell's palsy related to treatment start and age. Otol Neurotol. 2011 Jan. 32(1):141-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kanazawa A, Haginomori S, Takamaki A, Nonaka R, Araki M, Takenaka H. Prognosis for Bell's palsy: a comparison of diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007 Aug. 127(8):888-91. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Saito O, Aoyagi M, Tojima H, Koike Y. Diagnosis and treatment for Bell's palsy associated with diabetes mellitus. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1994. 511:153-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Allen D, Dunn L. Aciclovir or valaciclovir for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004. CD001869. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hato N, Yamada H, Kohno H, Matsumoto S, Honda N, Gyo K, et al. Valacyclovir and prednisolone treatment for Bell's palsy: a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Otol Neurotol. 2007 Apr. 28(3):408-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lockhart P, Daly F, Pitkethly M, Comerford N, Sullivan F. Antiviral treatment for Bell's palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Oct 7. CD001869. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- De Diego JI, Prim MP, De Sarriá MJ, Madero R, Gavilán J. Idiopathic facial paralysis: a randomized, prospective, and controlled study using single-dose prednisone versus acyclovir three times daily. Laryngoscope. 1998 Apr. 108(4 Pt 1):573-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Adour KK, Ruboyianes JM, Von Doersten PG, Byl FM, Trent CS, Quesenberry CP Jr, et al. Bell's palsy treatment with acyclovir and prednisone compared with prednisone alone: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996 May. 105(5):371-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Quant EC, Jeste SS, Muni RH, Cape AV, Bhussar MK, Peleg AY. The benefits of steroids versus steroids plus antivirals for treatment of Bell's palsy: a meta-analysis. BMJ. 2009 Sep 7. 339:b3354. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- de Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, Witterick IJ, Lin VY, Nedzelski JM, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009 Sep 2. 302(9):985-93. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Julian GG, Hoffmann JF, Shelton C. Surgical rehabilitation of facial nerve paralysis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1997 Oct. 30(5):701-26. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Pulec JL. Early decompression of the facial nerve in Bell's palsy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981 Nov-Dec. 90(6 Pt 1):570-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Olver JM. Raising the suborbicularis oculi fat (SOOF): its role in chronic facial palsy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Dec. 84(12):1401-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Gronseth GS, Paduga R. Evidence-based guideline update: steroids and antivirals for Bell palsy: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2012 Nov 27. 79(22):2209-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tucker ME. Diabetes in the Elderly Addressed in Consensus Report. Medscape Medical News. Accessed November 13, 2012. October 25, 2012.

- The facial nerve.

- The facial nerve.

Author

Danette C Taylor, DO, MS, FACN Medical Director, Movement Disorders, Mercy Health St Mary's; Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Neurology and Ophthalmology, Michigan State University College of Osteopathic Medicine

Danette C Taylor, DO, MS, FACN is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, American College of Osteopathic Neurologists and Psychiatrists, American Medical Association, American Osteopathic Association, International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Chief Editor

Selim R Benbadis, MD Professor, Director of Comprehensive Epilepsy Program, Departments of Neurology and Neurosurgery, Tampa General Hospital, University of South Florida Morsani College of Medicine

Selim R Benbadis, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, American Clinical Neurophysiology Society, American Epilepsy Society, American Medical Association

Disclosure: Serve(d) as a director, officer, partner, employee, advisor, consultant or trustee for: Bioserenity, Catalyst, Ceribell, Eisai, Jazz, LivaNova, Neurelis, Neuropace, SK Life Science Science, Sunovion, Takeda, UCB

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Catalyst, Jazz, LivaNova, Neurelis, SK Life Science, Stratus, UCB

Received research grant from: Cerevel Therapeutics; Ovid Therapeutics; Neuropace; Jazz; SK Life Science, Xenon Pharmaceuticals, UCB, Marinus, Longboard.

Additional Contributors

Acknowledgements

Edward Bessman, MD Chairman, Department of Emergency Medicine, John Hopkins Bayview Medical Center; Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Edward Bessman, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Dominique Dorion, MD, MSc, FRCSC, FACS Vice Dean and Associate Dean of Resources, Professor of Surgery, Division of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Sherbrooke Faculty of Medicine, Canada

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Thomas R Hedges III, MD Director of Neuro-Ophthalmology, New England Eye Center; Professor, Departments of Neurology and Ophthalmology, Tufts University School of Medicine

Thomas R Hedges III, MD is a member of the following medical societies: Alpha Omega Alpha, American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Medical Association, and North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

J Stephen Huff, MD Associate Professor, Emergency Medicine and Neurology, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center

J Stephen Huff, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Emergency Medicine, American Academy of Neurology, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Suzan Khoromi, MD Fellow, Pain and Neurosensory Mechanisms Branch, National Institute of Dental and Cranial Research, National Institutes of Health

Suzan Khoromi, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, American Pain Society, and International Association for the Study of Pain

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Milind J Kothari, DO Professor and Vice-Chair, Department of Neurology, Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine; Consulting Staff, Department of Neurology, Penn State Milton S Hershey Medical Center

Milind J Kothari, DO is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and American Neurological Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Andrew W Lawton, MD Medical Director of Neuro-Ophthalmology Service, Section of Ophthalmology, Baptist Eye Center, Baptist Health Medical Center

Andrew W Lawton, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Ophthalmology, Arkansas Medical Society, and Southern Medical Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Bruce Lo, MD Medical Director, Sentara Norfolk General Hospital; Assistant Professor, Assistant Program Director, Core Academic Faculty, Department of Emergency Medicine, Eastern Virginia Medical School

Bruce Lo, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American College of Emergency Physicians, Emergency Medicine Residents Association, Medical Society of Virginia, Norfolk Academy of Medicine, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Arlen D Meyers, MD, MBA Professor, Department of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, University of Colorado School of Medicine

Arlen D Meyers, MD, MBA is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, and American Head and Neck Society

Disclosure: Covidien Corp Consulting fee Consulting; US Tobacco Corporation Unrestricted gift Unknown; Axis Three Corporation Ownership interest Consulting; Omni Biosciences Ownership interest Consulting; Sentegra Ownership interest Board membership; Syndicom Ownership interest Consulting; Oxlo Consulting; Medvoy Ownership interest Management position; Cerescan Imaging Honoraria Consulting; GYRUS ACMI Honoraria Consulting

Kim Monnell, DO Neurology Consulting Staff, Department of Medicine, Bay Pines VA Medical Center

Kim Monnell, DO, is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology and American Osteopathic Association

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Hampton Roy Sr, MD Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Hampton Roy Sr, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Ophthalmology, American College of Surgeons, and Pan-American Association of Ophthalmology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Francisco Talavera, PharmD, PhD Adjunct Assistant Professor, University of Nebraska Medical Center College of Pharmacy; Editor-in-Chief, Medscape Drug Reference

Disclosure: Medscape Reference Salary Employment

Florian P Thomas, MD, MA, PhD, Drmed Director, Spinal Cord Injury Unit, St Louis Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Director, National MS Society Multiple Sclerosis Center; Director, Neuropathy Association Center of Excellence, Professor, Department of Neurology and Psychiatry, Associate Professor, Institute for Molecular Virology, and Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology, St Louis University School of Medicine

Florian P Thomas, MD, MA, PhD, Drmed is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Neurology, American Neurological Association, American Paraplegia Society, Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers, and National Multiple Sclerosis Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

B Viswanatha, MBBS, MS, DLO Professor of Otolaryngology (ENT), Chief of ENT III Unit, Sri Venkateshwara ENT Institute, Victoria Hospital, Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute; PG and UG Examiner, Manipal University, India and Annamalai University, India

B Viswanatha, MBBS, MS, DLO is a member of the following medical societies: Association of Otolaryngologists of India, Indian Medical Association, and Indian Society of Otology

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Brian R Younge, MD Professor of Ophthalmology, Mayo Clinic School of Medicine

Brian R Younge, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Medical Association, American Ophthalmological Society, and North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Craig H Zalvan, MD Director of Laryngology, Assistant Professor of Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, Department of Otorhinolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, ENT Faculty Practice

Craig H Zalvan, MD is a member of the following medical societies: American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery, American Bronchoesophagological Association, American College of Surgeons, American Laryngological Association, American Laryngological Rhinological and Otological Society, American Medical Association, Medical Society of the State of New York, New York County Medical Society, Triological Society, and Voice Foundation

Disclosure: Nothing to disclose.