Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing: Overview, Physiological Characteristics of Prostate-Specific Antigen, Other Prostate Cancer Markers (original) (raw)

Overview

Background

Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) is a protein produced by normal as well as neoplastic prostate cells. This enzyme participates in the dissolution of the seminal fluid coagulum and plays a key role in fertility. The highest amounts of PSA are found in the seminal fluid, although some PSA escapes the prostate and can be found in the serum. [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6]

Although detectable in all males, PSA is elevated in patients with prostate diseases (e.g., cancer, infection, and benign hypertrophy). Its levels can be greatly increased in patients with prostate cancer and the higher the levels, the greater is the tumor burden. [7]

PSA was originally identified by scientists in Japan. The government had requested that a means be found to identify semen in rape victims. The protein the researchers identified was called semenogelin.

In the United States, Richard Ablin et al independently identified this protein, which they called PSA. They were also looking for an identification method for semen in rape victims but were unaware of the Japanese research as the journal in which that work had been published was not readily available to them.

Because the protein has since been found in other parts of the body and is also present in small amounts in women, the term PSA is a bit of a misnomer.

PSA is not a true diagnostic test for prostate cancer, but rapidly rising values of PSA in the serum may be associated with prostate cancer. [8] The PSA level also tends to rise in males with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and usually increases as the prostate grows. PSA levels are also typically elevated in males with acute bacterial prostatitis. Even though "normal" PSA values are listed, each male has his own PSA value, and changes may reflect a number of events.

Since 1986, when tests for measuring PSA levels in serum were introduced into clinical practice, early diagnosis and management of prostate cancer has been revolutionized and much has been understood about the strengths and weaknesses of these assays. PSA testing not only helps identify males in whom a prostate biopsy would be appropriate but also assists in assessing the response to therapy, determining tumor progression, and, in its most controversial role, screening for prostate cancer. [9, 10, 11]

PSA remains the most widely used tumor marker in urology for prostate cancer detection, risk stratification, monitoring response to therapy, and surveillance for disease recurrence. [12]

Studies have indicated that a PSA of less than 1 confers a 1.5% probability of developing an active cancer. A PSA of greater than 4 increases this probability to 29.5%.

The prostate begins growing at around the age of 40 years and never stops. It may be walnut-sized in young males, but in males over age 40 years, the gland can attain a much greater size. As stated above, PSA tends to increase as the prostate becomes larger.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines recommend individualized, shared decision-making regarding PSA-based screening for males aged 55-69 years, considering patient values, risk factors (e.g., family history, African ancestry), and the balance of benefits and harms. Routine screening is not recommended for males aged 70 years and older. [13]

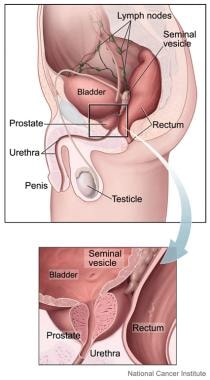

The image below depicts the anatomy of the prostate gland.

Prostate is a small gland, about the size and shape of a walnut, that is a part of the male reproductive system. It sits low in the pelvis, below the bladder and just in front of the rectum. Prostate helps make semen, which carries sperm from the testicles through the penis during ejaculation. It surrounds part of the urethra, which carries urine out of the bladder and through the penis. (Image courtesy of the National Cancer Institute)

Screening for prostate cancer

PSA levels have been used in screening large populations of males for prostate cancer and have been shown to be useful. Studies have found that PSA screening makes a real difference in the detection of this disease and subsequent patient survival.

Before the PSA era, an abnormality in the prostate had to be palpably evident before a biopsy would be performed, and nearly 70% of males diagnosed with prostate cancer already had extraprostatic or metastatic disease. Since the advent of PSA evaluation, fewer than 3% of males have been noted to have metastases at the time of diagnosis, and 75% of males have nonpalpable cancer, with the cancer being detected from a biopsy performed because of a rapidly rising or markedly elevated PSA level.

Despite the apparent survival advantage conferred by PSA screening, in 2008, the USPSTF recommended against screening for prostate cancer in males aged 75 years or older, and in 2012, the task force recommended against screening regardless of age. [14, 15] The USPSTF has since modified this position and currently supports a dialogue between doctors and patients aged 55-69 years, while also recommending that males aged 70 years or older not undergo PSA testing. The recommendations made by the task force are based on concerns that screening does not have a large impact on mortality from prostate cancer and that it is associated with potential harms, "including false-positive results that require additional testing and possible prostate biopsy; overdiagnosis and overtreatment; and treatment complications, such as incontinence and erectile dysfunction." [16]

Consistent with USPSTF's recommendations against prostate cancer screening, the detected incidence of prostate cancer dropped between 2007 and 2014, falling by approximately 40%. However, between 2014 and 2019, the incidence rose by 3% annually, with this increase having resulted from an annual rise of about 4.5% in the diagnoses of regional- and distant-stage prostate cancer. The increased incidence of advanced stage disease actually started as early as 2011. [15, 17]

Despite USPSTF's recommendations, urologists themselves are capable of deciding which screening tests and exams are necessary for each patient. Age should not be the determining factor in assessing whether a digital rectal examination (DRE) and a PSA test are needed. The patient and the physician should review the options and proceed accordingly. Even with the 2007-2014 detection reduction, many urologists have apparently not paid attention to the USPSTF's recommendations, as evidenced by a study by Kalavacherla et al, which indicated that a large percentage of older males are being screened for prostate cancer. The study, which used the 2020 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, found PSA screening rates to be 55.3% for males aged 70-74 years, 52.1% for males aged 75-79 years, and 39.4% for males aged 80 years or older. [18]

There is no specific age restriction for obtaining and tracking PSA. Males with a family history of prostate cancer can begin screening at the age of 40 years. The initial PSA sets the baseline.

The 2010 update of the American Cancer Society (ACS) guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer stresses the importance of involving patients to decide whether to test them for prostate cancer. The ACS notes that PSA testing may reduce the likelihood of dying from prostate cancer but that there may be risks associated with the treatment of prostate cancer that would not have developed if the disease had been left undetected. [19] Of course, there may also be risks if a cancer is not detected.

Most clinicians determine which males should undergo PSA testing on the basis of age, symptoms, family history, expected longevity, general medical condition, physical examination findings, and, often, the patient's request for the test. Urologists obtain PSA measurements for most of their male patients in the appropriate age group because they believe that they have an obligation to detect any prostate cancer at the earliest possible stage of its development.

The leading cause of malpractice claims against urologists is the failure to diagnose prostate cancer in a timely manner. Primary care physicians and internists are also increasingly being held liable for failure to obtain PSA testing for their patients and for failure to refer those with elevated PSA levels to a urologist.

Physicians have an obligation to discuss the risks and benefits of PSA testing with their patients. Ample information about PSA testing is also available from the American Cancer Society and the American Urological Association. Unfortunately, the internet contains a lot of misinformation on the subject.

To improve diagnostic accuracy, several adjunctive metrics and tests have been developed and validated [7] :

- PSA velocity (PSA-V)

- PSA density (PSAD)

- Percent free PSA (fPSA)

- Age-specific PSA reference ranges

- Iso-PSA

- Prostate Health Index and 4Kscore

The current strategy before performing a prostate biopsy is to obtain a prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. This imaging study can indicate the location of sites within the prostate that are suspicious of cancer. On a scale of 1-5, a 1/5 or a 2/5 indicates a low probability of cancer being present. A 4/5 or a 5/5 indicates a high probability, 70-90%, for the presence of cancer cells. A 3/5 indicates a 30-50% probability of cancer. By denoting abnormal sites within the prostate, MRI allows "targeted" biopsies to be done.

Physiological Characteristics of Prostate-Specific Antigen

Structure and attributes

PSA is a 33-kDa protein consisting of a single-chain glycoprotein of 237 amino acid residues, four carbohydrate side chains, and multiple disulfide bonds. It is homologous with the proteases of the kallikrein family. PSA may be referred to as human glandular kallikrein (hK)-3 to distinguish it from hK-2, another prostate cancer marker with which it shares 80% homology. A third kallikrein, hK-1, is found mainly in pancreatic and renal tissue but shows 73% and 84% homology with PSA.

Because of the similarities between these kallikreins, concern exists that both polyclonal and monoclonal assays may have cross-reactivity, which could affect PSA measurements. Lovgren et al demonstrated that very few monoclonal anti-PSA immunoglobulin (Ig) G molecules cross-react with hK-2. [20] Epitopes have been identified that are unique to PSA without possessing cross-reactivity to hK-2. This has led to the development of ultrasensitive immunoassays that are specific for PSA and hK-2, as well as assays that are fully cross-reactive with both proteins.

PSA is a neutral serine protease with biochemical attributes that are similar to the proteases involved in blood clotting. The role of proteases in the coagulation process has been studied extensively and applies to all serine proteases, including PSA. PSA splits the seminal vesicle proteins semenogelin I and II, resulting in liquefaction of the seminal coagulum.

The complete gene encoding PSA has been sequenced and localized to chromosome 19.

Sites of highest concentrations

PSA is found primarily in prostate epithelial cells and in the seminal fluid. The exact mechanism by which PSA gains access to the serum is unknown. The lumen of the prostate gland contains the highest concentration of PSA in the body. A number of barriers exist between the glandular lumen and the capillaries, including the basement membrane of the glands, the prostatic stroma, and the capillary endothelial cell. Diseases such as infection, inflammation, and cancer may produce a breakdown in these barriers, allowing more PSA to enter the circulation.

PSA levels can rise dramatically with a prostate infection, but they return to the reference range after the infection has healed. A vigorous prostate massage can also produce a brief elevation in PSA levels.

Low PSA levels have been identified in the urethral glands, endometrium, normal breast tissue, breast milk, salivary gland tissue, and urine of males and females. PSA is also found in the serum of females with breast, lung, or uterine cancer and in some patients with renal cancer.

Protein binding

Serine proteases are bound mostly to various serum proteins. A small percentage of serum PSA exists as fPSA, but the majority exists as complexed PSA (cPSA) and is bound to either α2-macroglobulin (AMG) or α1-antichymotrypsin (ACT). These are the two major serine protease inhibitors in the blood, constituting 10% of total serum protein. The ejaculate primarily contains fPSA, in a concentration of 1 million ng/mL.

When serum PSA is bound to ACT, two epitopes are left unmasked and can be detected with immunoassays. The complex formed with AMG is enveloped by this proteinase inhibitor so that no epitopes are left exposed for detection, and this lack of antibody attachment sites makes the PSA-AMG complex difficult to measure. However, the insignificant levels of the PSA-AMG complex indicate that this complex is unlikely to play a significant biological role in the serum.

Pharmacokinetics

The half-life and metabolic clearance rate of PSA have been determined from studies on patients undergoing radical prostatectomy. Stamey et al found the half-life to be 2.2 ± 0.8 days, [8] whereas Oesterling et al determined it to be 3.2 ± 0.1 days. [21] Because of the relatively long half-life of PSA, a minimum of 2-3 weeks is required for the serum PSA to reach its nadir after radical prostatectomy, at which point it should be undetectable.

Production in benign hyperplasia

A majority of PSA is produced by glands in the transitional zone of the prostate. This portion of the prostate is associated with BPH. The peripheral zone (PZ), where 80% of prostate cancers originate, produces very little PSA.

By measuring PSA before and after transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP), Stamey et al were able to calculate the amount of PSA produced per gram of benign prostatic tissue. [8] After comparing the weights of resected tissue and the change in serum PSA, the PSA level was 0.31 ± 0.25 ng/mL per gram of hyperplastic tissue. The polyclonal Yang assay was used for this study.

The Hybritech monoclonal assay produced a measurement of 0.5 ± 0.4 ng/mL. Using the monoclonal assay, Lee et al calculated a serum PSA elevation of 0.12 ng/mL per gram of benign prostatic tissue. [22]

Other physiological activities

Sutkowski et al suggested that PSA may regulate stromal tissue volume in males with BPH; using a tissue culture model, they demonstrated a concentration-dependent proliferative response of BPH-derived stromal cells to insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1. [23] PSA cleaves IGF-binding protein-3 (IGFBP3), and this decreases its affinity for IGF-1, which is an epithelial cell mitogen. Dissociation of the IGF-1–IGFBP3 complex makes IGF-1 available for binding to its receptor and stimulating cell proliferation.

In this study, [23] IGFBP3 inhibited the proliferative response in a concentration-dependent manner but had no effect on stromal cell proliferation. When stromal cells were incubated with PSA alone or with a combination of PSA, IGF-1, and IGFBP3, an increase in stromal cell numbers was noted and was dependent on PSA concentration. Zinc, an endogenous inhibitor of PSA enzymatic activity, attenuated the stimulatory effect of PSA at intraprostatic physiological concentrations.

Fortier et al demonstrated that PSA inhibited endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and invasion by 50% or more and inhibited endothelial cell responses to both fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). [24] On the basis of observations that patients with breast cancer who had higher PSA levels had a better prognosis than those who had low levels, the authors hypothesized that PSA may have antiangiogenic properties.

To evaluate this hypothesis, the investigators evaluated the effects of PSA on endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. [24] They treated bovine and human endothelial cells with purified human PSA and then stimulated them with FGF-2 and VEGF. In another experiment to evaluate the ability of PSA to inhibit lung metastases of melanoma cells, they administered B16BL6 melanoma cells intravenously to mice and then administered PSA for 11 consecutive days.

The authors concluded that PSA, in addition to its other physiological functions, may also act as an endogenous antiangiogenic protein. [24] This finding may explain the slow progression of cancer in some patients, and the authors postulate that strategies that inhibit PSA production may be counterproductive.

Other Prostate Cancer Markers

Human glandular kallikrein–2

hK-2 is a serine protease that has approximately 80% structural homology with PSA (hK-3). It is responsible for the conversion of the inactive pro-PSA zymogen to the enzymatically active PSA in vitro, which is a prerequisite for formation of PSA–α1-ACT and other complexes. As prostate cancer cells become more anaplastic, hK-2 levels rise, whereas PSA levels tend to fall. Concentrations of PSA and hK-2 are high in prostatic and seminal fluid but low in the blood.

The Goteborg screening study evaluated 604 males with a total PSA (tPSA) higher than 3. These males underwent DRE, transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS), and sextant prostate biopsies. Cancer was identified in 144 males (23.8%). Significantly higher levels of hK-2 and tPSA were found in those with cancer, whereas the ratio of fPSA to tPSA was lower. The optimum equation predicting the presence of cancer was as follows:

hK-2 × tPSA/fPSA

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) was 0.81. At a sensitivity of 75%, the specificity of tPSA was 47%, the sensitivity of tPSA/fPSA was 63%, and the sensitivity of hK-2 × tPSA/fPSA was 74%. At any higher sensitivity, tPSA consistently had decreasing specificity, whereas the other two measures produced similar results.

Males with localized cancer who were treated with radical prostatectomy had lower hK-2 levels if the cancer was confined to the organ compared with those who had extraprostatic extension of cancer. The tPSA levels in this same cohort were not different.

Prostate-specific membrane antigen

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a selective antigenic marker of prostate epithelial cells that can be found in the serum. Bostwick et al found that this marker is expressed in 70% of benign epithelial cells, 78% of prostate intraepithelial neoplastic cells, and 80% of invasive cancer cells. [25] PSMA is expressed to a greater extent than PSA in higher-grade cancers.

PSMA is a 100-kDa type II membrane protein. The gene for PSMA is located on the short arm of chromosome 11. The gene has been fully sequenced and cloned and encodes for a glycoprotein consisting of three domains: an intracellular domain, a transmembrane region, and a large 707-amino acid extracellular sequence making up the bulk of the molecule. Two variations of the PSMA gene have been identified and characterized, but their individual roles have not been elucidated.

Nonprostate expression of PSMA occurs in the proximal tubule cells of the kidney, salivary glands, and small bowel (particularly the duodenum); PSMA has high folate hydrolase activity that is essential for absorbing ingested folates. Anti-PSMA monoclonal antibodies react to the endothelium of malignant tissue but not to normal endothelium. Various carcinomas express PSMA consistently and strongly in their tumor-associated neovasculature; however, a similar expression has not been found in prostate cancer neovasculature.

The development of immunoassays and Western blot–based assays for PSMA has permitted an increasing number of studies. PSMA levels seem to correlate with stage and tumor volume. After radical prostatectomy, PSMA levels become undetectable, but they rise if the tumor recurs. Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing with PSMA primers has been used to detect circulating prostate cancer cells. This method detects tumor cells at concentrations as low as 1 per 10 million lymphocytes.

The use of this method for clinical decision-making has been limited. With this technology, cancer cells can be identified in the circulation and in the bone marrow of patients with all stages of prostate cancer. This indicates that cancer cells begin leaving the prostate early in the development of the disease, but most of them do not survive, and their identification does not correlate with patient prognosis or survival.

Ferrari et al demonstrated that PSMA RT-PCR technology was superior to standard histological techniques for detecting micrometastases in lymph nodes removed during radical prostatectomy. [26] In this study, lymph nodes were obtained from 33 patients with Gleason scores of 7 or higher and serum PSA levels of 10 or higher who were undergoing radical prostatectomy.

Routine pathology examinations identified cancer cells in four (12%) of these patients. [26] PSA or PSMA expression occurred in 27 (82%) of the patients. The four patients with positive lymph node findings also had positive results for both PSA and PSMA. Among the 29 patients with no histological evidence of disease, 23 (79%) tested positive with RT-PCR. In these 23 patients, PSMA was detected more frequently than PSA, though in two patients, only PSA was found.

Although these findings demonstrate that prostate cancer cells or fragments of these cells can be found in pelvic lymph nodes, the status of these cells and their viability cannot be ascertained. This observation is another indication of the early egress of cancer cells from the prostate, but there is not necessarily any correlation with patient prognosis and survival.

PSMA serves as the basis for the use of gallium-68 (68Ga) PSMA positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) scanning in males with biochemical recurrence after definitive treatment of acinar prostate cancer. This imaging study is employed to detect metastatic cancer, its primary use being to identify prostate cancer cells in lymph nodes and in the prostate base. Fluorine-18 piflufolastat or 18F-DCFPyL PSMA PET-CT scanning has also been shown to be more sensitive in detecting recurrent prostate cancer than standard imaging.

PSMA is being evaluated as a means of providing therapy. When PSMA is used as an immunotherapeutic agent, dendritic cells are primed with the antigen and infused into the patient. This is intended to produce a specific immune response to prostate cells. With PSMA used as a guide to identify and target prostate cells, radioactive isotopes and cytotoxic agents can be delivered to these cells. Lutetium-177 (177Lu)–PSMA-617 is one such agent and has been investigated in males with castrate-resistant prostate cancer.

Cell cycle inhibitor p27

The cell cycle inhibitor p27 is a putative tumor suppressor gene. Loss of p27 is associated with a poor prognosis in patients with breast, colorectal, and prostate carcinoma. In males treated with radical prostatectomy, loss of p27 expression correlates with an increased probability of cancer recurrence and lower survival rates. Decreased p27 expression is also associated with high-grade cancer cells, positive surgical margins, seminal vesicle invasion, and lymph node metastases.

Serum insulin-like growth factor

IGF-1, its binding protein (IGFBP), and its receptor (IGF receptor) have been implicated in the development of prostate cancer. PSA cleaves IGF-1 from its binding protein, allowing this potent growth factor to act on prostate epithelial cells.

Plasma concentrations of IGF-1 have been associated with an increased risk for prostate cancer. In the Physicians' Health Study, 152 cases of prostate cancer were matched with 152 control individuals from a population of 14,916 physicians. Serum samples assayed for IGF-1 at the outset of the study found a positive association with the subsequent development of prostate cancer. Males in the highest quartile of IGF-1 had a relative risk of 2.4 compared with those in the lowest quartile.

The predominant IGF-1 binding protein, IGFBP-3, has growth-inhibiting properties that diminish the effect of IGF-1. After correcting for IGFBP-3 levels, the risk of developing prostate cancer was 4.5 times greater for the highest quartile than for the lowest quartile.

The clinical usefulness of this assay has yet to be demonstrated because alternative explanations for these findings may exist. Prostate size and a large overlap in actual values limit the utility of the test but do provide additional information regarding the biology of prostate cancer.

Procedure for Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing

Preparation of sample

PSA testing requires a blood sample, typically collected into a red top tube without anticoagulant. Fasting is not required for PSA testing [7] . The blood sample for PSA testing should be centrifuged, and the serum should be separated within 2-3 h. If the assay is not performed within the next 2-3 h, the serum should be frozen. Reliability of the protein is believed to be maintained when the specimen is frozen at less than −20° C for several weeks. Specimens frozen at temperatures below −70° C can be stored for at least a month.

Prostate-specific antigen assays

Before the second PSA Standardization Conference held at Stanford University in 1994, two assays were predominantly used: the Yang, which used a polyclonal antibody, and the Hybritech, which used a monoclonal antibody. (Other PSA assays are now available; see Prostate-Specific Antigen Assays.) Differences existed in the purification techniques for PSA. As a result, these and other newly developed assays delivered results that could not be compared, rendering patient treatment difficult and the interpretation of research data nearly impossible.

Riehmann et al reported interlaboratory variations as high as 55% in patients without prostate cancer. At this conference, an agreement was made to use the purification method of Sensabaugh and Blake, which became the international standard. However, standardization issues persist, and data interpretation remains confusing.

Interpretation of results

When two different assays are used to measure the same serum sample, discrepancies can occur as a result of differences in assay calibration, assay kinetics, or different detection standardization of PSA in the serum. Although correlation coefficients between assays may be high, biases can occur, with one assay reporting a PSA result that may be as much as 20-30% lower than another.

Results obtained in one assay cannot be extrapolated to another. This variability is crucial in clinical situations such as screening and in the use of assay results to calculate PSAD, PSA-V, and age-specific reference ranges.

Assay variability is also important when the PSA level is in the low (0.1-4 ng/mL) or intermediate (4-10 ng/mL) range. At these levels, a result that is elevated or markedly different from previous results will lead to repetitive PSA testing in an individual patient to confirm or disprove the change. The results may critically influence decisions about the need for a biopsy or the possible recurrence of cancer following surgery or radiation therapy, as well as the evaluation of patients with BPH and prostatitis.

When the PSA level is high (> 10 ng/mL), the same variability for an initial PSA test is less relevant, because a biopsy will be performed regardless of the assay result.

The performance of a marker for the detection of cancer is frequently evaluated by using an ROC curve, which measures sensitivity and specificity simultaneously and permits the comparison of assays. Marker performance improves as sensitivity and specificity approach 100%. The area under the test curve is used as a quantitative measurement of the accuracy of the test. The more closely the curve approaches the upper corner of the graph, the better the performance of the test.

Since the introduction of the first assay, numerous commercial assays have become available. The first-generation assays have lower limits of 0.2 ng/mL for PSA detection, the second-generation assays have detection limits of less than 0.1 ng/mL, and the third-generation ultrasensitive assays can detect PSA at levels as low as 0.003 ng/mL. Currently, these low levels are primarily of interest in detecting recurrent cancer after radical prostatectomy.

PSA doubling times have been shown to be an important indicator in deciding the need for a biopsy and in monitoring patients with prostate cancer. However, if PSA levels are below 0.5 ng/mL, doubling times lose their accuracy.

In most clinical situations, little difference exists between the data obtained with different assays as long as the same assay method is being used consistently. Wymenga et al, comparing a first-generation assay (IMx) with a second-generation assay (Immulite) in males with BPH and prostate cancer, found that for most of the males, these assays were equivalent. [27]

Although these assays showed strong concordance and limited variability, the variability may be of clinical importance for a single individual. The discrepancy between the values is magnified when they are used to evaluate age-specific reference ranges and to calculate PSAD and PSA-V.

Interpretation of PSA test results requires both clinical evaluation and patient education. Patients are increasingly aware of the PSA test because the media frequently reports which PSA tests are considered worthless and which should be performed regularly. Patients often compare their results with each other and appreciate the physician's opinion regarding the interpretation of different values.

Interpretation [7] :

- 0-2.5 ng/mL is low

- 2.6-10 ng/mL is slightly to moderately elevated

- 10.1-19.9 ng/mL is moderately elevated

- 20 ng/mL and above is significantly elevated

A significant rise in PSA following therapy may suggest disease recurrence or progression. [7]

Factors Influencing Prostate-Specific Antigen Levels

For clinical purposes, PSA is considered specific for the prostate gland but not specific for prostate cancer. A major limitation of PSA as a prostate cancer marker is the overlap in values between BPH and prostate cancer. Normal, hyperplastic, and neoplastic epithelial cells all make PSA, but the amount of PSA produced by cancer cells is 10 times higher per gram of tissue than the amount produced by normal or hyperplastic tissue.

Hyperplastic tissue and epithelial-stromal ratio

The interpretation of PSA may vary according to the amount of BPH tissue and the epithelial-stromal ratio. Most PSA is produced in the hyperplastic transitional zone of the prostate. A relatively small amount of PSA is produced in the PZ, where 80% of prostate cancers originate. Cancers developing in the transitional zone tend to produce large amounts of PSA.

High-grade cancer cells tend to lose their ability to produce PSA. A Gleason grade 5 prostate cancer produces less PSA than a grade 3 cancer. Some patients with advanced prostate cancer may have low or undetectable PSA levels.

Pharmacological factors

The serum PSA level can be altered by various medications. Finasteride and dutasteride, 5-α reductase inhibitors that are commonly prescribed for the treatment of BPH, can produce a 50% decrease in tPSA levels within 6 months of therapy. This alteration fluctuates widely, ranging from an 80% decrease to a 20% increase. After 3-4 months of therapy, another PSA measurement can be obtained to establish a new baseline.

fPSA levels are unaffected by finasteride or dutasteride. PSAD — i.e., tPSA divided by prostate volume — is affected by 5-α reductase medications because the major PSA-producing region of the prostate is reduced in volume.

α1-adrenergic antagonists, which are frequently used to treat the symptoms of BPH, do not alter PSA levels, nor do herbal products such as saw palmetto.

Any medications that alter testosterone levels can affect the serum PSA level. The use of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists and antagonists to stop testosterone production by the testicles is a cornerstone in the treatment of prostate cancer. This manipulation produces a profound reduction in PSA levels, usually making them undetectable. Raising testosterone levels may increase PSA levels but not to the same degree as reducing testosterone production.

Statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and thiazide diuretics are associated with modest but statistically significant reductions in PSA (6-26% with long-term use), potentially confounding cancer screening and monitoring. [28]

Ejaculation within 24 h of blood testing is associated with elevated PSA levels. [7] In 67% of males older than 50 years who were tested, PSA levels showed a 41% mean increase (0.8 ng/mL) 1 h after ejaculation.

Noncancerous prostatic disease and urological manipulation

The serum PSA level can also be altered by noncancerous prostatic disease and urological manipulations. Recent urinary tract infections, [7] acute prostatitis, subclinical or chronic prostatitis, and urinary retention cause elevation in PSA levels. Nadler et al reported that serum PSA levels higher than 4.0 ng/mL in 148 males with subclinical prostatitis could be attributed to their disease because all these males had negative findings from biopsies repeated on multiple occasions. [29]

DRE may cause a transient increase in tPSA and fPSA, with maximal effect at 30-60 min post-exam; the rise is usually modest but can be up to 70% in some cases, especially if blood is drawn immediately after DRE. For optimal accuracy, PSA should be measured before DRE or several hours later. [7, 30]

Prostate massage, biopsy, TURP, and rigid cystoscopy can cause significant, sometimes multifold, increases in PSA, with elevations lasting from several days (after massage) to weeks (after biopsy or TURP). After needle biopsy, PSA may increase up to 9.5-fold and can take up to 2-4 weeks to return to baseline. [30, 31]

The time it takes for PSA to return to baseline levels depends on the precipitating event and the half-life (2.2-3.2 days). After a biopsy, 2-4 weeks may elapse before PSA levels return to their original levels. If an infection occurs as a result of the biopsy, the return to baseline levels may take longer. After ejaculation, PSA levels have been reported to return to their original levels within 48 h, whereas fPSA returns to baseline at 6 h because of its shorter half-life (2 h).

After relief of urinary retention, PSA levels decrease by 50% in 24-48 h. In acute prostatitis, which produces large increases in PSA, the return to baseline depends on the resolution of the infection, which may take 6-8 weeks or longer. PSA levels have been used to determine the duration of antimicrobial therapy in males with acute bacterial prostatitis.

No diurnal variation in PSA levels exists, and PSA measurements in the same individual tend to remain unchanged when obtained at daily, weekly, and monthly intervals. Carter et al found that PSA levels measured from serum samples frozen for more than 25 years remained stable. [32]

Data suggest transient PSA elevations following COVID-19 infection and vaccination — analogous to other inflammatory triggers. [33] Tobacco use is associated with higher PSA levels and should be considered when interpreting results. [34]

Race and age

The incidence of prostate cancer is higher in Black males than in White males. [35, 36] Reports indicate that PSA levels are higher in Black males, even when age, clinical stage, and Gleason grade are controlled for. Moul et al suggested that that these higher levels are related to the larger (i.e., 1.3-2.5 times greater) tumor volumes found in these males. [37] Morgan et al evaluated 411 Black males who had prostate cancer and noted that 40% of cases would have been missed if the traditional age-specific reference ranges had been used. [38]

PSA levels tend to increase with age; this increase is related to prostate volume. Most PSA is made in the transition zone of the prostate, and this region of the prostate increases in volume in males with BPH. [36, 39]

Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing for Detection of Prostate Cancer

The introduction of PSA testing into clinical practice has greatly increased the detection of localized prostate cancer cases and, by doing so, has decreased the diagnosis of regional and metastatic disease. PSA testing has had such a profound clinical effect that questions have arisen regarding the significance of the cancers that are being detected.

Stage, grade, tumor volume, and PSA testing are used to determine whether a prostate cancer is clinically significant or insignificant. However, there is no generally accepted precise definition for this distinction.

The goal of early detection of prostate cancer is to identify clinically significant cancers at a time when treatment is most likely to be effective. The risk for mortality from prostate cancer is significant in those with moderate- to high-grade tumors. This is especially true in younger males. Long-term survival is compromised when the cancer has spread beyond the confines of the prostate, into the regional lymph nodes, and to distant sites.

Several studies have shown that with a PSA cutoff of 4.0 ng/mL, clinically insignificant cancers are detected in fewer than 20% of males, but nearly 50% of all the cancers detected because of an elevated PSA level are localized, and these patients are candidates for potentially curative therapy. Only a small proportion of prostate cancers detected by PSA testing and treated with radical prostatectomy are low-volume (< 0.2 cm3) and low-grade (Gleason grade 1-2) tumors.

PSA levels between 4.0 and 10.0 ng/mL increase the odds of clinically significant, intracapsular cancer by 1.5- to 3-fold, and extracapsular disease by 3- to 5-fold. PSA levels > 10.0 ng/mL are associated with a substantially higher risk for non–organ-confined disease, and levels ≥ 20 ng/mL are highly predictive of advanced or metastatic cancer. A significant proportion of cancers detected in the PSA "gray zone" (4-10 ng/mL) are localized, but the risk for overdiagnosis remains. [7, 40, 41]

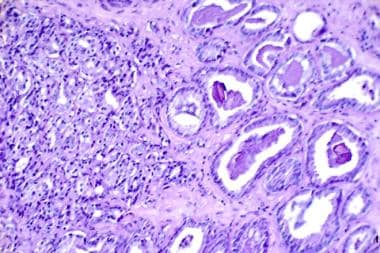

A higher Gleason score (≥ 7) is generally associated with larger tumor volumes, or evidence of extraprostatic extension, and a higher risk for disease progression and mortality. [42] Nearly one third of cancers identified because of PSA screening and treated with radical prostatectomy show evidence of capsular penetration, high Gleason grades (4-5) (see the image below), large tumor volumes, or distant metastases. These prognostic risk factors do not always correlate with survival, but they do increase the possibility of tumor recurrence and progression.

A histological slide showing prostate cancer (hematoxylin-eosin, 300×). On the right is a somewhat normal tissue with a Gleason value of 3 (out of 5) with moderately differentiated cancer. On the left is a less normal tissue with a Gleason value of 4 (out of 5) that is highly undifferentiated. The Gleason score is a sum of two worst areas of the histological slide. (Image courtesy of the National Cancer Institute)

Free, complexed, and total prostate-specific antigen and prostate-specific antigen density

fPSA is a major indicator for the diagnosis and management of prostate cancer. However, within a range of 4-10 ng/mL, in which 75% of males do not have cancer, the fPSA level lacks specificity. At this range, four males must undergo biopsy to identify one male with cancer.

Stenman et al reported that males with prostate cancer had more cPSA than fPSA, unlike males with BPH. [43] After the development of an immunoassay, the investigators demonstrated that the ratio of fPSA to tPSA, or f/tPSA, was lower in males with prostate cancer. In the PSA range of 4-10 ng/mL, tPSA segregates adequately between males with or without cancer. The f/tPSA ratio is a more discriminatory indicator.

A seven-institution study that investigated 63 males with BPH, 30 males with prostate cancer (prostate size > 40 cm3), and 20 males with small prostates found PSA levels in all the males to be in the range of 4-10 ng/mL. The median f/tPSA was 0.188 in patients with BPH, 0.159 in those with prostate cancer, and 0.092 in those with small prostates. These findings imply that the prostate size is an important variable in selecting a cutoff value for fPSA.

For males whose prostates are smaller than 40 cm3, an f/tPSA of 0.137 or lower is used to detect 90% of the cancers, and 76% of the negative biopsy findings can be eliminated. For males with prostates larger than 40 cm3, a cutoff of 0.205 allows the detection of 90% of the cancers, and 38% of the negative biopsy findings can be eliminated. If the patient has a normal-sized prostate on DRE, a value of 0.234 is necessary to detect 90% of the cancers, sparing 31.3% of the patients an unnecessary biopsy.

Brawer et al, comparing the specificity of tPSA and f/tPSA at various sensitivities, found that at a sensitivity of 80% and a tPSA cutoff of 4.11, the specificity was 35.6%, compared with 46.2% for f/tPSA at a cutoff point of 19%. [44] At a sensitivity of 90% with a tPSA cutoff of 3.4, the specificity was 25.3%, compared with 26.2% for f/tPSA at a cutoff point of 24%. In a large population of males with PSA levels of 4-10 ng/mL and a cutoff point of 25% or less, 95% of the cancers would be detected, and 20% of the patients would be spared a biopsy.

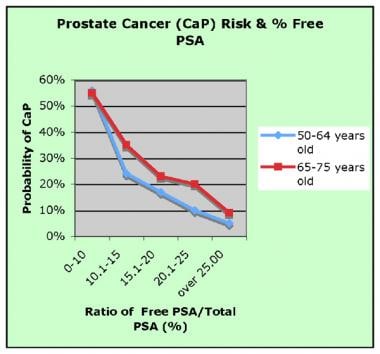

Probability of prostate cancer (CaP) in relation to free-to-total prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ratio. (Image courtesy of Wikipedia)

fPSA is most useful in males with persistently elevated PSA levels who previously underwent a biopsy with negative findings. As the percentage of fPSA declines, the probability that a cancer is present increases. Conversely, a higher percentage of fPSA indicates a lower probability of cancer. Even with this added information, the decision to perform a biopsy on any given patient ultimately depends on the physician's judgement.

The value of fPSA in the staging of prostate cancer has not been conclusively demonstrated, though several studies indicate that a correlation may exist. In the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, the f/tPSA significantly segregated those who developed cancer from those who did not up to 15 years before the diagnosis. Twelve males with stage T3 or T4 disease who had Gleason scores of 7 or higher or positive margins after radical prostatectomy had lower f/tPSA values than 8 with less aggressive cancers. tPSA was elevated only 5 years before diagnosis.

PSA density is calculated by dividing tPSA by the prostate volume. Values of less than 0.1 are considered favorable, indicating a low risk for prostate cancer.

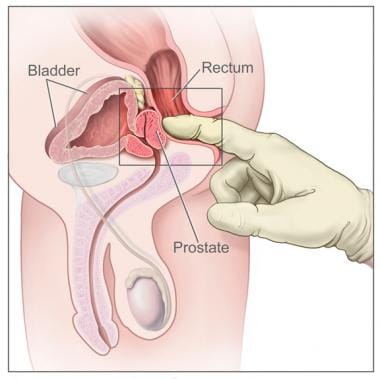

Prostate-specific antigen testing plus digital rectal examination

Although PSA testing detects more cancers than DRE (see the image below), a combination of the two methods is better. DRE detects more cancers at the PSA cutoff of 4.0 ng/mL, but this may not be the case if the cutoff is lowered to 3.0 ng/mL.

Digital rectal examination. The image shows a side view of the male reproductive and urinary anatomy, including the prostate, rectum, and bladder; it also shows a gloved and lubricated finger inserted into the rectum to feel the prostate. (Image courtesy of the National Cancer Institute)

The detection of prostate cancer with a combination of PSA and DRE has been evaluated by a number of investigators. Among males with prostate cancer whose PSA level was lower than 4 ng/mL, DRE findings were normal in 4-9% and positive in 10-20%. When the PSA level was higher than 4 ng/mL, negative DRE results were found in 12-32% of patients, and positive DRE results were present in 42-72%.

Clinical stage T1c, defined as prostate cancer detected on a biopsy performed because of an elevated PSA level and normal DRE findings, is currently the most diagnosed stage of prostate cancer. Detection of T1c tumors increased the probability of the cancer being organ-confined at radical prostatectomy to 60%. Adding DRE to the patient evaluation demonstrated that 60% of the tumors were organ-confined. This adds support to the contention that cancers detected because of PSA testing are likely to be clinically significant.

Improving Sensitivity of Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing

PSA testing with a cutoff of 4.0 ng/mL has a sensitivity of 67.5-80%, which implies that 20-30% of cancers are missed when only the PSA level is obtained. Sensitivity can be improved by lowering the cutoff or by monitoring PSA values so that a rise in PSA level of more than 20-25% per year or an increase of 0.75 ng/mL in 1 year would trigger performance of a biopsy regardless of the PSA value.

The specificity of PSA at levels higher than 4.0 ng/mL is 60-70%. Specificity can be improved by using age-adjusted values, PSA-V, and the ratio of fPSA to tPSA. Another method is to adjust PSA according to the size of the prostate or volume determinations of the transitional zone, which produces most of the PSA, and the PZ, which produces less PSA but a majority of prostate cancers.

In the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer, Schroder et al studied a strategy for the early detection of prostate cancer that excluded DRE results and used a PSA cutoff of 3.0 ng/mL as the only indication for a biopsy. [45] This protocol was compared with one in which a PSA level of 4.0 ng/mL or higher or the presence of a positive DRE or TRUS was the indication for a biopsy. In a follow-up study, Schroder et al confirmed a substantial reduction in mortality from prostate cancer as a result of PSA testing. [46]

Prostate cancer detected with the new strategy (i.e., PSA ≥ 3.0 ng/mL) had a similar distribution of Gleason scores but a larger proportion of organ-confined disease. Tumor volumes were smallest in patients whose PSA levels were lower than 2.9 ng/mL. Minimal disease was present in 50% of these patients compared with 28% of those whose PSA levels were 3.0-3.9 ng/mL.

Lowering the biopsy indication to a PSA level of 3.0 ng/mL without a DRE raised the positive predictive value from 18.2% to 24.3%. The number of biopsies required to detect one patient with cancer changed from 5.2 to 3.4. The characteristics of the cancers detected with this strategy had minimal variation from protocols combining PSA, DRE, and TRUS.

Babaijan et al studied the incidence of prostate cancer in a screening population of males with a PSA level of 2.5-4.0 ng/mL; on the basis of the biopsy data, they concluded that 67.6% of the detected cancers were clinically significant. Of the 268 males who participated in this screening, 151 agreed to have prostate biopsies. Cancer was identified in 37 (24.5%) of these males.

PSA levels correlate with the detection rate of prostate cancer. Males older than 50 years have a 20-30% possibility of having prostate cancer if their PSA level is higher than 4.0 ng/mL. If the PSA level is between 2.5 and 4.0 ng/mL, a biopsy is likely to detect cancer in 27% of males. For PSA levels greater than 10 ng/mL, the possibility of positive biopsy findings increases to 42-64%.

Even at PSA levels of 4-10 ng/mL, Partin et al found that one half of the patients treated with radical prostatectomy had extraprostatic extension. [47] When the PSA level is higher than 10 ng/mL, the risk for extraprostatic cancer increases considerably. In the same study, Partin et al noted that 80% of males with PSA levels higher than 20.0 ng/mL had extraprostatic disease.

Recommendations for Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing

According to a 2019 position statement from the European Association of Urology (EAU), a baseline PSA test in males aged 45 years at risk for prostate cancer should be used in combination with family history, ethnicity, and other factors to establish individualized screening frequency. [48] Subsequent screening intervals should be determined by the baseline PSA value in combination with family history, ethnicity, and other relevant risk factors. The EAU supports the use of risk calculators, multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging, and, where appropriate, biomarkers to guide biopsy decisions, aiming to reduce overdiagnosis and overtreatment while maintaining early detection of clinically significant disease. By 20 years after testing, structured PSA screening in males aged 55-69 years is associated with a reduction in prostate cancer–specific mortality, with approximately 100 males needing to be screened to prevent one prostate cancer death. [49]

The 2023 American Urological Association (AUA)/Society of Urologic Oncology guideline strongly recommends PSA-based screening in combination with shared decision-making for males with a life expectancy greater than 10 years. The guideline suggests offering a baseline PSA test between ages 45 and 50 years, with subsequent testing intervals tailored to individual risk and baseline PSA. The AUA endorses the use of available online risk calculators and emphasizes the importance of repeat PSA testing for newly elevated values before proceeding to secondary biomarkers, imaging, or biopsy. DRE may be included but is not mandatory for screening. [50, 51]

The ACS advises that males at average risk should discuss the risks and benefits of PSA screening with their clinician starting at the age of 50 years and at the age of 45 years for those at higher risk (Black males or those with a first-degree relative diagnosed with prostate cancer before the age of 65 years). For males with a life expectancy of less than 10 years, screening is not recommended. Males with an initial PSA below 2.5 ng/mL may be screened every 2 years, while those with a PSA of 2.5 ng/mL or higher should be tested annually. The ACS also recommends that males with a strong family history of prostate cancer be considered for more frequent testing and that all patients with consistently elevated PSA levels (> 4.0 ng/mL) be referred to a urologist for further evaluation. [52]

Carter et al evaluated the frequency with which PSA testing could be conducted without compromising prostate cancer detection in males with low PSA levels and normal DRE findings. [53] Using data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, they determined that 95% of males with PSA levels of 4 ng/mL or less had potentially curable disease. In males with pretreatment PSA levels of 4-5 ng/mL, 89% of the cancers were potentially curable, and only one third were considered small tumors.

From these findings, the investigators concluded that potentially curable prostate cancer cases are not compromised when PSA is measured every other year in males with PSA levels of 2 ng/mL or less, as long as the DRE findings are normal. [53]

Smith et al reported a 4% PSA conversion from a baseline PSA of less than 2 ng/mL to a level of more than 4 ng/mL when patients were observed semiannually for 4 years.

Using the same Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging database, Carter et al further evaluated the association of baseline PSA, age, and prostate cancer detection. [53] They conducted a prospective study of males aged 60-65 years who underwent serial PSA testing. These males were observed until they either were diagnosed with prostate cancer or reached the age of 75 years. The time of cancer detection was defined as the date on which a PSA level above 4.0 was detected.

All those diagnosed with cancer had PSA levels higher than 4.0 ng/mL, and 14 of 15 patients with cancer that would have been detected by a PSA conversion among the 65-year-old cohort had PSA levels of 1.1 ng/mL or higher. [53] The authors postulated that if PSA testing was discontinued in males aged 65 years whose PSA level was 0.5 ng/mL or less, 100% of the cancers would be detected by age 75 years. If PSA testing was discontinued in males aged 65 years whose PSA was 1.0 ng/mL or less, 94% of the cancers would be detected by age 75 years.

Refinements to Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing

Prostate-specific antigen density

In 1992, in an effort to correlate PSA levels with prostate volume, Benson et al introduced the concept of PSAD. [54, 55] This concept was based on the knowledge that most PSA is produced in the transitional zone of the prostate; cancer cells produce more PSA per unit volume than benign cells. PSAD is defined as tPSA divided by prostate volume, as determined by means of TRUS.

Theoretically, PSAD could help distinguish between prostate cancer and BPH in males whose PSA levels are between 4 and 10 ng/mL. The value of PSAD is limited because of its dependence on the individual performing prostate volume measurement.

In addition, the BPH volume does not always correlate with serum PSA values because of variation in the epithelial-to-stromal ratios that exists between individual patients. PSA is made only by epithelial cells, which produce a lower PSA level even though the total volume of the prostate is high.

Seaman et al reported that the PSAD value could improve the detection rate of cancer at a cutoff of 0.15. [56] In a large multicenter trial, Catalona et al reported that nearly 50% of cancers would be missed with a cutoff of 0.15. [57] Brawer et al studied 107 males with PSA levels in the 4-10 ng/mL range and found no statistical difference between those with positive biopsy findings and those with negative findings with the 0.15 cutoff value. [44]

Prostate-specific antigen transition zone density

Kalish introduced PSA density of the transition zone (PSA-TZ) as a refinement to the original PSAD. This refinement is predicated on the following two assumptions:

- That measuring transition zone volume with TRUS is more accurate than measuring the entire prostate volume because of the difficulty in measuring the true border of the apex in the longitudinal view.

- That most of the PSA entering the circulation arises from the transition zone.

Zisman et al have offered a new index using the PZ fraction of PSA to predict the presence of prostate cancer in males with PSA levels of 4-10 ng/mL. [58] They pointed out that the PZ contributes little to tPSA. The PZ fraction can be calculated using the following formula:

tPSA × (total prostate volume − TZ volume)/total prostate volume

PZ volume is measured by subtracting TZ volume from total prostate volume while neglecting the central zone.

Zisman et al compared the positive and negative predictive values using tPSA, PSAD, PSA-TZ, and PSA peripheral zone density (PSA-PZ). The efficacy rates of PSA and PSA-TZ were similar, at 60%; PSA-PZ had a 70% efficacy rate, PSAD an 80% rate. The negative predictive values were superior to the positive predictive values, ranging from 78% to 83% for PSA, from 78% to 88% for PSAD, from 87% to 92% for PSA-TZ, and from 81% to 100% for PSA-PZ.

On ROC curves, both PSA-TZ and PSA-PZ were significantly larger than PSA and PSAD. When patients with negative DRE findings were studied using the ROC curve, the area under the PSA-PZ curve was larger than that under the PSA-TZ curve.

Prostate-specific antigen velocity

In 1992, Carter et al introduced the concept of PSA-V in an effort to improve the ability of PSA to detect prostate cancer cases. [32] PSA-V is used to monitor the change in PSA over time using longitudinal measurements. Greater changes in PSA-V were detected in males with cancer than in those without cancer 5 years before the diagnosis was made. Additional studies have shown that this difference can be detected up to 9 years before prostate cancer diagnosis.

PSA-V is calculated by means of the following equation:

i/2 [(PSA2 − PSA1/time 1 in years) + (PSA3 − PSA2/time 2 in years)]

where PSA1 is the first PSA measurement, PSA2 the second, and PSA3 the third. To obtain maximal benefit from the results, at least three PSA measurements are needed during a 2-year period or at least 12-18 months apart.

A PSA-V of 0.75 ng/mL or greater per year was suggestive of cancer (72% sensitivity, 95% specificity). A PSA-V of 0.75 ng/mL or greater correlated with the diagnosis of cancer in 72% of the patients, and only 5% had no cancer.

PSA-V testing has several limitations, including the following:

- PSA-V is difficult to calculate

- PSA is not cancer-specific

- PSA levels vary significantly with time and with different assays

Nevertheless, in some situations, a PSA-V value greater than 0.75 ng/mL per year is useful to determine the need for initial or repeat biopsy.

Age-Specific Prostate-Specific Antigen Reference Ranges

The standard PSA reference range of 0.0-4.0 ng/mL does not account for age-related volume changes in the prostate that are related to the development of BPH. Oesterling et al proposed that the use of age-related reference ranges would improve cancer detection rates in younger males and increase the specificity of PSA testing in older males. [21] They reported an overall specificity of 95% with the following reference ranges:

- 40-49 years: 0-2.5 ng/mL

- 50-59 years: 0-3.5 ng/mL

- 60-69 years: 0-4.5 ng/mL

- 70-79 years: 0-6.5 ng/mL

Using these ranges in a study of 4600 males with clinically localized prostate cancer, Partin et al detected 74 additional cancers in males aged 60 years or younger. [47] Pathology results were favorable in males undergoing radical prostatectomy; 80% had organ-confined disease with a Gleason score of 7 or less. In males older than 60 years, fewer than 3% of the cancers missed were nonpalpable, 95% of which had favorable histology results. The potential detection of prostate cancer increased 18% in younger males and decreased 22% in older males.

A study by Kovac et al indicated that in males aged 55-60 years, baseline PSA levels are an effective indicator of long-term prostate cancer risk. Actuarial 13-year incidences of clinically significant prostate cancer diagnosis in this cohort were as follows [59] :

- Baseline PSA 0.49 ng/mL or less: 0.4%

- Baseline PSA 0.50-0.99 ng/mL: 1.5%

- Baseline PSA 1.00-1.99 ng/mL: 5.4%

- Baseline PSA 2.00-2.99 ng/mL: 10.6%

- Baseline PSA 3.00-3.99 ng/mL: 15.3%

- Baseline PSA 4.0 ng/mL or above: 29.5%

The investigators suggested that when their baseline PSA level is low, males aged 55-60 years require less frequent prostate cancer screening. [59]

Reissigl et al studied the effect of biopsy rates and prostate cancer detection using age-specific ranges and a PSA cutoff of 4 ng/mL. [60] The data came from an Austrian screening study of more than 21,000 males aged 45-75 years. They reported an 8% increase in cancer diagnosis of organ-confined disease in males younger than 59 years. In males older than 60 years who had normal findings on DRE, 21% fewer biopsies were performed, while 4% of organ-confined cancers were missed.

Oesterling et al [21] proposed a different age-specific reference range for Black males. With this reference range, the specificity varied among age groups as follows:

- 40-49 years: 0-2 ng/mL; 93% specificity

- 50-59 years: 0-4 ng/mL; 88% specificity

- 60-69 years: 0-4.5 ng/mL; 81% specificity

Whether age-specific PSA reference ranges have any significant advantage over the standard PSA cutoff value of 4.0 ng/mL remains controversial. In an early detection study involving 6600 males, Catalona et al reported that the standard PSA cutoff value was optimal for all age groups. [61]

Littrip et al concluded that the standard reference range remains the most effective and least costly means of screening. These investigators argue that a lower PSA cutoff in younger males could result in additional unnecessary biopsies and greater healthcare costs. In contrast, raising the cutoff level for older males could result in fewer cancers being detected.

The use of age-specific reference ranges in clinical practice results in the diagnosis of more cancers in males younger than 60 years at the expense of more negative findings on biopsy. However, early, potentially curable cancers should be diagnosed in this age group. An increasing number of males in the fifth and sixth decades of life are being diagnosed with significant cancers as a result of the use of age-specific reference ranges in addition to PSAD and PSA-V.

Most cancer cases are detected in older males (i.e., males with larger prostates and higher PSA levels). If the goal of testing is to identify the greatest number of cancers, all older males should be tested. If the intent is to diagnose the same percentage of cancers in each age group, the age-adjusted reference range could be used.

Brawer observed that the use of age-adjusted PSA values results in a slightly enhanced positive predictive value, compared with the standard of 0-4 ng/mL, but a significantly lower cancer detection rate. Moreover, on the basis of the United States Life Table actuarial values, a significant increase in population longevity would occur if 4.0 ng/mL was used as the cutoff rather than age-adjusted cutoffs. [62]

Integrating polygenic risk scores (PRS) with age-specific PSA cutoffs improves specificity and reduces missed cancers without increasing false positives. For example, in a large Chinese cohort, age- and PRS-adapted cutoffs were lower than traditional ranges, with recommended cutoffs for low-PRS males being 1.42-2.24 ng/mL (by age bracket) and higher for males with high PRS. [63]

There is no easy, infallible method of determining when biopsies may be avoidable and when they are necessary. Until a perfect test is developed, which is unlikely to happen, this determination must be made on the basis of clinical judgment and experience.

Prostate-Specific Antigen Testing to Monitor Therapy

A pattern of increasing PSA levels after local therapy distinguishes between local and distant recurrence. Distant disease can be predicted if the PSA level does not become undetectable after radical prostatectomy, begins to rise within 12 months, or has a doubling time of 6 months. The same characteristics apply to radiation therapy and cryotherapy, although the time to nadir is prolonged.

Patients whose PSA level becomes detectable 24 months or more after radical prostatectomy likely have local recurrence. Patients with PSA doubling times of 12 months or more after surgery, radiation therapy, or cryotherapy are likely to have local recurrence.

The ultrasensitive PSA assays have increased the lead time for identifying biochemical recurrence after definitive local therapy. These assays can measure PSA levels as low as 0.001 ng/mL. Ellis et al reported a 10-fold increased sensitivity in 24 patients who underwent radical prostatectomy. [64] The patients' PSA levels were previously undetectable on the conventional assays.

Using multivariate analysis, Yu et al demonstrated that ultrasensitive PSA measurement possessed significant advantages over tumor volume and positive surgical margins with respect to the ability to detect early relapse. [65]

After radical prostatectomy

Serial PSA measurements provide the most effective means of detecting early recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Postoperatively, most males have a rapid decline in their PSA levels, which are expected to become undetectable within 1 month.

A PSA level that is elevated after a period during which it was undetectable connotes the presence of prostate cells somewhere in the body. These cells may be from residual normal glandular elements remaining in the bladder wall or at the apex of the prostate, but generally, a detectable and rising PSA level indicates the presence of residual cancer cells.

The preoperative PSA level and the interval between surgery and the detection of PSA with standard assays can be used to predict disease-free survival and the pattern of recurrence. Pound et al analyzed data from 1623 males who had a radical prostatectomy [66] and found that the 5-year actuarial recurrence-free rate was 54% for males whose initial PSA levels were greater than 20 ng/mL, 72% for those whose PSA levels were 10.1-20 ng/mL, and 82% for those whose PSA levels were 4.1-10 ng/mL. [66]

The clinical course of these patients was followed for 2-8 years. [66] The timing of PSA detection was predictive of local recurrence as opposed to distant disease recurrence. During the first year after surgery, 7% of patients with detectable PSA had local recurrence; 93% had distant metastases with or without local recurrence. After the second year, the respective rates were 61% and 39%.

Patel et al reported that PSA doubling time was a better predictor of time to clinical recurrence than preoperative PSA, stage, and pathologic Gleason score. [67] A PSA doubling time of 6 months or less after surgery indicated metastatic disease. The investigators reported that 80% of 77 patients who had detectable PSA levels postoperatively and a doubling time longer than 6 months remained clinically disease-free compared with 64% who had a PSA doubling time shorter than 6 months.

Pound et al used a doubling time of 10 months to derive similar conclusions. [66] They cautioned against treating patients with long PSA doubling times too early because most of these males lived for many years before the evidence of clinical disease was detected.

Postoperative PSA-V and pathologic stage have been studied as a means of determining treatment failure and the need for additional intervention. A detectable PSA level in a patient with micrometastatic lymph node disease, a Gleason score greater than 7, or seminal vesicle invasion indicates distant metastatic disease.

Partin et al used multivariate analysis to study PSA-V, Gleason score, and pathologic stage as predictors of local recurrence and distant metastases. [47] In patients whose PSA levels became detectable 1 year or longer after surgery, a PSA-V lower than 0.75 correlated with local recurrence in 94% of patients, whereas a PSA-V higher than 0.75 predicted distant disease in more than 50% of patients.

A detectable PSA level within the first two postoperative years is indicative of distant metastases and correlates with other risk factors such as stage and grade. These associations are important in determining which patients might benefit from local radiation therapy after prostatectomy.

After radiation therapy

A consensus has not been reached on what constitutes an acceptable PSA level after radiation therapy. PSA levels decline slowly, and a nadir may not be reached for a median of 17 months. In some patients, a transient rise in the PSA level may occur at 12 months after completion of therapy; the level usually decreases during the subsequent year.

Two methods are generally used to assess the patient prognosis. In the first method, a nadir of 0.5 ng/mL correlates with a biochemical-free survival of 5 years. The American Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology recommends another method, in which a biochemical recurrence is defined as three consecutive rises above the nadir with measurements obtained at 3- to 6-month intervals.