Hepatitis B: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology (original) (raw)

Overview

Practice Essentials

Hepatitis B infection is a worldwide healthcare problem, especially in developing areas. The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is commonly transmitted via body fluids such as blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. [1]

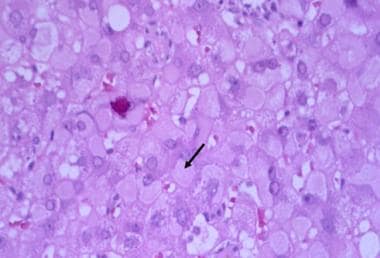

The hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain below depicts "ground-glass" cells seen in approximately 50-75% of livers affected by chronic HBV infection.

Hepatitis B. Under higher-power magnification, ground-glass cells may be visible in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Ground-glass cells are present in 50% to 75% of livers with chronic HBV infection. Immunohistochemical staining is positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg.)

Signs and symptoms

The pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of hepatitis B are due to the interaction of the virus and the host immune system, which leads to liver injury and, potentially, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Patients can have either an acute symptomatic disease or an asymptomatic disease.

Icteric hepatitis is associated with a prodromal period, during which a serum sickness–like syndrome can occur. The symptomatology is more constitutional and includes the following:

- Anorexia

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Low-grade fever

- Myalgia

- Fatigability

- Disordered gustatory acuity and smell sensations (aversion to food and cigarettes)

- Right upper quadrant and epigastric pain (intermittent, mild to moderate)

Patients with fulminant and subfulminant hepatitis may present with the following:

- Hepatic encephalopathy

- Somnolence

- Disturbances in sleep pattern

- Mental confusion

- Coma

- Ascites

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Coagulopathy

Patients with chronic hepatitis B infection can be immune tolerant or have an inactive chronic infection without any evidence of active disease, and they are also asymptomatic. Patients with chronic active hepatitis, especially during the replicative state, may have symptoms similar to those of acute hepatitis.

See Clinical Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

The physical examination findings in hepatitis B disease vary from minimal to impressive (in patients with hepatic decompensation), according to the stage of the disease.

Examination in patients with acute hepatitis may demonstrate the following:

- Low-grade fever

- Jaundice (10 days after appearance of constitutional symptomatology; lasts 1-3 mo)

- Hepatomegaly (mildly enlarged, soft liver)

- Splenomegaly (5-15%)

- Palmar erythema (rarely)

- Spider nevi (rarely)

Signs of chronic liver disease include the following:

- Hepatomegaly

- Splenomegaly

- Muscle wasting

- Palmar erythema

- Spider angiomas

- Vasculitis (rarely)

Patients with cirrhosis may have the following findings:

- Ascites

- Jaundice

- History of variceal bleeding

- Peripheral edema

- Gynecomastia

- Testicular atrophy

- Abdominal collateral veins (caput medusa)

Laboratory studies

The following laboratory tests may be used to assess the various stages of hepatitis B disease:

- Alanine aminotransferase and/or aspartate aminotransferase levels

- Alkaline phosphatase levels

- Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase levels

- Total and direct serum bilirubin levels

- Albumin level

- Hematologic and coagulation studies (eg, platelet count, complete blood count [CBC], international normalized ratio)

- Ammonia levels

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- Serologic tests

The serologic tests should include the following laboratory studies:

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

- Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)

- Hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) immunoglobulin M (IgM)

- anti-HBc IgG

- Hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe)

- hepatitis B virus (HBV) deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)

Imaging studies

The following radiologic studies may be used to evaluate patients with hepatitis B disease:

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning

- Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Procedures

Liver biopsy, percutaneous or laparoscopic, is the standard procedure to assess the severity of disease in patients with features of chronic active liver disease (ie, abnormal aminotransferase levels and detectable levels of HBV DNA).

See Workup for more detail.

Management

The primary treatment goals for patients with hepatitis B infection are to prevent progression of the disease, particularly to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). [2] Pegylated interferon alfa (PEG-IFN-a), entecavir, and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate are the FDA-approved agents in the treatment of hepatitis B disease.

Pharmacotherapy

The following medications are used in the treatment of hepatitis B:

- Nucleos(t)ide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (eg, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, tenofovir alafenamide, lamivudine)

- Hepatitis B/hepatitis C agents (eg, adefovir dipivoxil, entecavir, PEG-IFN-a 2a, interferon alfa-2b)

Dietary changes

For individuals with decompensated cirrhosis (prominent signs of portal hypertension or encephalopathy), the following dietary limitations are indicated:

- A low-sodium diet (1.5 g/day)

- High-protein diet (ie, white-meat protein [eg, chicken, turkey, fish])

- Fluid restriction (1.5 L/day) in cases of hyponatremia

Liver transplantation

Orthotopic liver transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with fulminant hepatic failure who do not recover and for patients with end-stage liver disease due to hepatitis B disease.

See Treatment and Medication for more detail.

Background

Hepatitis B is a worldwide healthcare problem, especially in developing areas. An estimated one third of the global population is infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Approximately 250-350 million people have lifelong chronic infection, [3] with approximately 1.5 million new cases every year. [4] Approximately 0.5% of patients spontaneously seroconvert annually from having the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) to having the hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs). [5] (See Pathophysiology, Etiology, and Epidemiology.)

Complications from hepatitis B include progression to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and, rarely, cirrhosis. Extrahepatic disease can involve glomerulonephritis and polyarteritis nodosa, as well as various dermatologic, cardiopulmonary, joint, neurologic, hematologic, and gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations. (See Pathophysiology.)

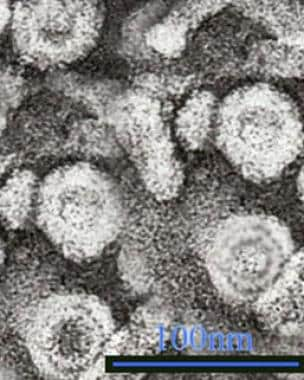

Since the 1970s, considerable progress has also been made regarding the knowledge of the epidemiology, virology, natural history, and treatment of the hepatitis B virion, a hepatotropic virus particle (see the image below). In addition, ongoing vaccination programs have been successful in many countries and territories in decreasing the prevalence of HBV disease (eg, Taiwan). [6] (See Etiology, Epidemiology, Workup, Treatment, and Medication.)

Hepatitis B. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepadnavirus, highly resistant to extremes of temperature and humidity, that invades the hepatocytes. The viral genome is a partially double-stranded, circular DNA linked to a DNA polymerase that is surrounded by an icosahedral nucleocapsid and then by a lipid envelope. Embedded within these layers are numerous antigens that are important in disease identification and progression. Within the nucleocapsid are the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and precore hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and on the envelope is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) from Graham Colm and Wikipedia, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

HBV is transmitted vertically from mother to fetus, hematogenously, and sexually. The outcome of this infection is a complicated viral-host interaction that results in either an acute symptomatic disease or an asymptomatic disease. Some patients clear HBV and develop anti-HBs; however, as long as the individual has antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg), he or she is at risk for reactivation because HBV infection remains an incurable disease, similar to Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), and Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections. Alternatively, a patient may develop a chronic infection state with positivity for HBsAg. Late consequences are cirrhosis and the development of HCC in 15-30% of individuals. [6, 7, 8, 9]

In immunocompetent adults, less than approximately 4% of HBV infections become chronic, whereas up to 90% of perinatally infected infants will have chronic disease. [10] Among children who acquire HBV infection between ages 1 and 5 years, 30-50% become chronically infected.

Taiwan launched a nationwide HBV vaccination program in 1984. The prevalence of HCC in children younger than 20 years has been reported to be 0.5% or less. [6]

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), by the end of 2010, the HBV vaccine had been routinely introduced in 179 countries, with a global coverage of 75%. Coverage in the Americas was at 89%; in Europe, 78%; in Africa, 76%; and in Southeast Asia, 52%. [11]

Antiviral treatment may be effective in approximately 95% of the patients who are treated with first-line oral therapy, as defined by undetectable HBV DNA. For those who are treated with interferon, about 17% have persistent HBV DNA suppression. For selected candidates, liver transplantation currently seems to be the only viable treatment for the later stages of hepatitis B infection, with a posttransplantation viral suppression of greater than 90-95%. (See Treatment and Medication.)

See also Liver Disease in Pregnancy, Hepatitis A, Hepatitis C, Hepatitis D, and Hepatitis E.

Pathophysiology

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepadnavirus (see the following image), with the virion consisting of a 42-nm spherical, double-shelled particle composed of small spheres and rods and with an average width of 22 nm. [12, 13, 14, 15, 16] It is an exceedingly resistant virus, capable of withstanding extreme temperatures and humidity. HBV can survive when stored for 15 years at –20°C, for 24 months at –80°C, for 6 months at room temperature, and for 7 days at 44°C. Indeed, the approximately 400-year-old mummified remains of a child found on a mountain top in Korea had HBV in the liver that could be sequenced, and a viral genotype C was identified. [17]

Hepatitis B. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a hepadnavirus, highly resistant to extremes of temperature and humidity, that invades the hepatocytes. The viral genome is a partially double-stranded, circular DNA linked to a DNA polymerase that is surrounded by an icosahedral nucleocapsid and then by a lipid envelope. Embedded within these layers are numerous antigens that are important in disease identification and progression. Within the nucleocapsid are the hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and precore hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and on the envelope is the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Transmission electron micrograph (TEM) from Graham Colm and Wikipedia, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

Viral genome

The viral genome of hepatitis B consists of a partially double-stranded, circular DNA molecule of 3.2 kilobase (kb) pairs that encodes the following 4 overlapping open reading frames:

- S (the surface, or envelope, gene): Encodes the pre-S1, pre-S2, and S proteins

- C (the core gene): Encodes the core nucleocapsid protein and the e antigen; an upstream region for the S (pre-S) and C (pre-C) genes has been found

- X (the X gene): Encodes the X protein

- P (the polymerase gene): Encodes a large protein promoting priming ribonucleic acid (RNA) ̶ dependent and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase and ribonuclease H (RNase H) activities

Surface gene

The S gene encodes the viral envelope. There are five main antigenic determinants: (1) a, common to all hepatitis B surface antigens (HBsAg), and (2-5) d, y, w, and r, which are all epidemiologically important and identify the serotypes.

Core gene

The core antigen, HBcAg, is the protein that encloses the viral DNA. It can also be expressed on the surface of the hepatocytes, initiating a cellular immune response.

The e antigen, HBeAg, which is also produced from the region in and near the core gene, is a marker of active viral replication. It serves as an immune decoy and directly manipulates the immune system; it is thus involved in maintaining viral persistence. HBeAg can be detected in patients with circulating serum HBV DNA who have “wild type” infection. As the virus evolves over time under immune pressure, core promotor and precore mutations emerge, and HBeAg levels fall until the level is not measurable by standard assays.

Individuals who are infected with the wild type virus often have mixed infections, with core and precore mutants in up to 50% of individuals. They often relapse with HBeAg-negative disease after treatment.

X gene

The role of the X gene is to encode proteins that act as transcriptional transactivators that aid viral replication. Evidence strongly suggests that these transactivators may be involved in carcinogenesis.

Antibody production

The production of antibodies against HBsAg (anti-HBs) confers protective immunity and can be detected in patients who have recovered from HBV infection or in those who have been vaccinated.

Antibody to HBcAg (anti-HBc) is detected in almost every patient with previous exposure to HBV and indicates that there is a minute level of persistent virus, as demonstrated by the risk of reactivation in individuals who undergo immune suppression regardless of their anti-HBs status.

The immunoglobulin M (IgM) subtype of anti-HBc is indicative of acute infection or reactivation, whereas the IgG subtype is indicative of chronic infection. The activity of the disease cannot be understood using this marker alone, however.

Antibody to HBeAg may be suggestive of a nonreplicative state if there is undetectable HBV DNA or the emergence of the core/precore variants and of chronic HBV HBeAg-negative disease.

Variants of HBV

With the newest polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay techniques, scientists are able to identify variations in the HBV genome (variants) as far back as 1995, even in patients who are positive for HBeAg. Mutations of various nucleotides such as the 1896, 1764, and 1768 (precore/core region) processing the production of the HBeAg have been identified (HBeAg-negative strain). [18]

These variants are generally less efficient at viral replication without HBeAg and tend to have lower viral loads, although with a suspected higher risk of development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). [19]

The prevalence of the HBeAg-negative virus varies from one region to another. Estimates indicate that among patients with chronic HBV infection, 50-60% of those from Southern Europe, the Middle East, Asia, and Africa, as well as 10-30% of patients in the United States and Europe, have been infected with this strain.

Immune response

The pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of hepatitis B infection are due to the interaction of the virus and the host immune system. The immune system attacks HBV and causes liver injury, the result of an immunologic reaction when activated CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes recognize various HBV-derived peptides on the surface of the hepatocytes. Impaired immune reactions (eg, cytokine release, antibody production) or a relatively tolerant immune status result in chronic hepatitis. In particular, a restricted T-cell–mediated lymphocytic response occurs against the HBV-infected hepatocytes. [20, 21]

The final state of HBV disease is cirrhosis. With or without cirrhosis, however, patients with HBV infection are at risk of developing HCC. [6, 7, 8] In the United States, hepatitis B–associated HCC cases most often occur in the setting of vertical transmission (mother to fetus) in patients of Asian descent.

Viral life cycle

The five stages that have been identified in the viral life cycle of hepatitis B infection are briefly discussed below. Different factors have been postulated to influence the development of these stages, including age, sex, immunosuppression, and coinfection with other viruses.

Stage 1: Immune tolerance

This stage, which lasts approximately 2-4 weeks in healthy adults, represents the incubation period. For newborns, the duration of this period is often decades. Active viral replication is known to continue despite little or no elevation in the aminotransferase levels and no symptoms of illness.

Stage 2: Immune active/immune clearance

In the immune active stage, also known as the immune clearance stage, an inflammatory reaction with a cytopathic effect occurs. Serum HBeAg can be identified, and a decline in the levels of HBV DNA is seen in some patients who are clearing the infection. The duration of this stage for patients with acute infection is approximately 3-4 weeks (symptomatic period). For patients with chronic infection, 10 years or more may elapse before cirrhosis develops, immune clearance takes place, HCC develops, or the chronic HBeAg-negative variant emerges.

Stage 3: Inactive chronic infection

In the third stage, the inactive chronic infection stage, the host can target the infected hepatocytes and HBV. Viral replication is low or no longer measurable in the serum, and anti-HBe can be detected. Aminotransferase levels are within the reference range. It is likely that at this stage, an integration of the viral genome into the host's hepatocyte genome takes place. HBsAg still is present in the serum.

Stage 4: Chronic disease

The emergence of chronic HBeAg-negative disease can occur from the inactive chronic infection stage (stage 3) or directly from the immune active/clearance stage (stage 2).

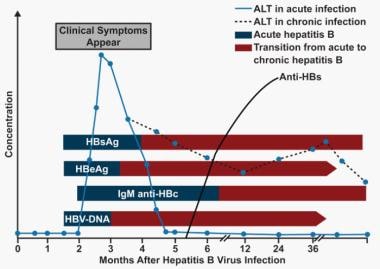

Stage 5: Recovery

In the fifth stage, the virus cannot be detected in the blood by DNA or HBsAg assays, and antibodies to various viral antigens have been produced. The image below depicts the serologic course of HBV infection.

Hepatitis B. Serologic course of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. The flat bars show the duration of seropositivity in self-limited acute HBV infection. The pointed bars show that HBV DNA and e antigen (HBeAg) can become undetectable during chronic infection. Only immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies to the HBV core antigen (anti-HBc) are predictably detectable after resolution of acute hepatitis or during chronic infection. Antibody to hepatitis B surface antigen (anti-HBs) is generally detectable after resolution of acute HBV infection but may disappear with time. It is only rarely found in patients with chronic infection and does not indicate that immunologic recovery will occur or that the patient has a better prognosis. ALT = alanine transaminase. (Adapted from Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373(9663):582-92.)

Genotypes and disease progression

Ten different genotypes (A through J), representing a divergence of the viral DNA of about 8%, have been identified. [22] The prevalence of the genotypes varies in different countries. The progression of the disease seems to be more accelerated and the response to treatment with antiviral agents is less favorable for patients infected by genotype C, compared with those infected by genotype B. However, much of this can be explained by the presence of core and precore mutations found in multivariate analysis. [23, 24]

It has been confirmed that the risk of HCC is related to higher serum HBV DNA levels and the duration of HBV DNA presence, with an even higher risk if there is an increasing level of hepatitis B viral load, the presence of genotype C, and the presence of mutations in the precore and basal core promoter regions.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Even the presence of hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) in the absence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA is significantly related to an increased risk for HCC, although surveillance for HCC is not recommended in the affected group unless cirrhosis is present. In the United States, the estimated annual incidence of HCC in patients infected with hepatitis B is 818 cases per 100,000 persons. In Taiwan, the annual incidence of this malignancy in patients with hepatitis B and cirrhosis is 2.8%. Familial clustering of HCC has been described among families with hepatitis B in Africa, the Far East, and Alaska.

HBV and HCV coinfection

The prevalence of HCC among patients with HBV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection is higher than in those with a single infection. The rate of development of HCC per 100 person years of follow-up is 2% in patients with cirrhosis and HBV infection, 3.7% in patients with HCV infection, and 6.4% in patients with dual HBV and HCV infection. These findings point to a probable synergistic effect on the risk of HCC.

HBV and HDV coinfection

Individuals coinfected with hepatitis D (delta) virus (HDV) are thought to have a higher rate of HCC and cirrhosis, with the virus reportedly increasing the risk of HCC 3-fold and mortality rates 2-fold in patients with HBV cirrhosis. [25]

Worldwide, the prevalence of HDV coinfection among patients infected with HBV is 0-30%, with the highest prevalence in Mongolia, Southeast Turkey, and the Orinoco River in South America. The speculation that HDV may promote hepatocarcinogenesis in these patients has been investigated with varying results. The prevalence of anti-delta antibody among patients with cirrhosis with and without HCC was not significantly different in one study, whereas most other investigations show the delta virus to be more aggressive, with higher rates of cirrhosis and cancer. [25, 26, 27]

Possible pathogenic mechanisms

The mechanism by which chronic hepatitis B infection predisposes to the development of HCC is not clear. Cirrhosis is a cardinal factor in carcinogenesis. Hepatocyte inflammation, necrosis, mitosis, and features of chronic hepatitis are major factors in nodular regeneration, fibrosis, and carcinoma. Liver cell dysplasia, defined as cellular enlargement, nuclear pleomorphism, and multinucleated cells affecting groups or whole nodules, may be an intermediate step. The high cell-proliferation rate increases the risk of HCC.

The fact that the facultative liver stem cells are capable of bipotent differentiation into hepatocytes or biliary epithelium, termed oval cells, may play an important role in the pathogenesis. These cells are small, with oval nuclei and scant pale cytoplasm.

Oval cells are prominent in actively regenerating nodules and in liver tissue surrounding the cancer. They appear to be the principal producers of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP). Although the cellular targets of carcinogenesis have not been identified, some evidence from experimental animal models suggests that oval cell proliferation is associated with an increased risk for the development of HCC.

Although cirrhosis is found in the majority of patients with HCC, it is not obligatory, because individuals with chronic infection may develop HCC even without the evidence of cirrhosis.

HBV has been speculated to have intrinsic hepatocarcinogenic activity, interacting with host DNA in different ways. After entering the hepatocyte, viral DNA is integrated within the genome. The site of integration is not constant but usually involves the terminal repeat sequences. Chromosomal deletions, translocations, rearrangements, inversions, or even duplications of normal DNA sequencing accompany integration.

Transactivation of the function of genes controlling transcriptional factors (ie, insulinlike growth factor II [IGF-2], transforming growth factor-alpha [TGF-a], TGF-beta, cyclin-a [a protein that controls cell division], epidermal growth factor-r [EGFR], retinoic acid receptor [RAR]), and oncogenes such as c-myc, fos, ras (activating the internal signal transduction cascade upregulating ras/mitogen–activated kinase, c-Jun N terminal kinase, nuclear factor–kB [NF-kB], Jak-1-STAT, src- dependent pathways) influence normal hepatocyte differentiation or cell cycle progression.

Furthermore, the integrated part of HBV controlling the production of the HBxAg (antigen for the X gene of HBV) is overexpressed. These observations suggest that the site of viral genomic integration into the host's DNA is not the only factor.

Most likely, the HBxAg produced by these sequences is the transactivating factor, because it has been found to bind to a variety of transcription factors such as CREB (cyclic adenosine monophosphate [cAMP]–response element-binding protein) and ATF-2 (activating transcription factor 2), altering their DNA-binding specificity. Thus, the ability of the HBV pX protein to interact with cellular factors broadens the DNA-binding specificity of these regulatory proteins and provides a mechanism for pX to participate in transcriptional regulation. This shifts the pattern of host gene expression relevant to the development of HCC.

Additionally, HBxAg has been postulated to bind to the C-terminus and inactivate the product of the tumor suppressor gene TP53, as well as to do the following:

- Sequester TP53 in the cytoplasm, resulting in the abrogation of TP53 -induced apoptosis (although controversy exists regarding this concept)

- Reduce the ability for nucleotide excision repair by directly acting with proteins associated with DNA transcription and repair such as XPB and XPD

- Reduce p21WAF1 expression, which is a cell cycle regulator

- Bind to protein p55sen, which is involved in the cell fate during embryogenesis and is found in the liver of patients with hepatitis B, thus altering its function

The levels of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-a), a proinflammatory cytokine, are also upregulated. The transcriptional transactivation of nitric oxide (NO) synthetase II by pX and the elevated levels of TNF-a are responsible for the high levels of NO found in these patients. NO is a putative mutagen that develops through several mechanisms of functional modifications of TP53, DNA oxidation, deamination, and formation of the carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds. A second transactivator is encoded in the pre-S/S region of the HBV genome, stimulating the expression of the human proto-oncogenes c-fos and c-myc; this upregulates the expression of TGF-a by transactivation.

Glomerulonephritis

The most common type of glomerulonephritis described in association with hepatitis B is membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN), found mainly in children. However, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN) and, even more rarely, immunoglobulin (Ig) A nephropathy, have also been identified.

The prevalence rate of glomerulonephritis among patients with chronic hepatitis B is not well known, although observations have been made in children that suggest a range of 11-56.2%. However, such a high prevalence is not recognized in the United States; this may be because of the differences in epidemiology of HBV, which may be predominantly perinatal in other geographic areas of the world (see Epidemiology).

A previous history of chronic liver disease is not present in the majority of patients with chronic hepatitis B at presentation, and most of them have no clinical or biochemical findings to suggest acute or chronic liver disease. However, liver biopsies often demonstrate features of chronic hepatitis. In addition, serologic markers of an HBV replicative state are often evident, and complement activation is suggested by low levels of C3 and C4.

Generally, the most prominent finding among affected children is MGN, primarily with capillary wall deposits of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). In contrast, adults present with features of MPGN with mesangial and capillary wall deposits of HBsAg. A rare overlap between membranous nephropathy and IgA nephropathy has also been described.

Possible pathogenic mechanisms

The mechanism by which patients with chronic hepatitis B develop glomerulonephritis is not completely understood. One possible explanation is that HBV antigens (ie, HBsAg, HBeAg) act as triggering factors, eliciting immunoglobulins and thus forming immune complexes, which are dense, irregular deposits in the glomerular capillary basement membranes. HBV DNA has been identified by in situ hybridization in kidney specimens, distributed generally in the nucleus and cytoplasm of epithelial cells and mesangial cells of glomeruli and in the epithelial cells of renal tubules.

Polyarteritis nodosa

An association between hepatitis B and arteritis has been described when HBsAg is present in serum and in vascular lesions. Evidence for a cause-and-effect relationship is further supported by a high prevalence (36-69%) of HBsAg in patients with polyarteritis nodosa (PAN). This very serious complication presents early during the course of hepatitis B, and the incidence is high among certain populations, such as Alaskan Eskimos.

The pathogenesis of PAN is not clear. Circulating immune complexes containing HBsAg, immunoglobulins (IgG and IgM), and complement have been demonstrated by immunofluorescence in the walls of the affected vessels and may trigger the onset of PAN. However, whether these represent the primary etiology of the disease remains unclear.

The clinical manifestations of PAN include the following:

- Cardiovascular (eg, hypertension [sometimes severe], pericarditis, heart failure)

- Renal (eg, hematuria, proteinuria, renal insufficiency)

- Gastrointestinal (GI) (eg, abdominal pain, mesenteric vasculitis)

- Musculoskeletal (eg, arthralgias, arthritis)

- Neurologic (eg, mononeuritis)

- Dermatologic (eg, rashes)

Significant proteinuria (>1 g/day), renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.58 mg/dL), GI and central nervous system involvement, and cardiomyopathy are associated with increased mortality.

The course of PAN is independent of the severity and progression of the liver disease. Among patients with PAN, 20-45% die as a consequence of vasculitis in 5 years, despite treatment, with the mortality rate being similar whether patients are HBsAg seropositive or seronegative.

Etiology

Hepatitis B infection, caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV), is commonly transmitted via body fluids such as blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. [1] Consequently, sexual contact, accidental needle sticks or sharing of needles, blood transfusions, and organ transplantation are routes for HBV infection. Infected mothers can also pass the infection to their newborns during the delivery period (vertical transmission). [1]

Genetics of infection with hepatitis B

Several genes, many having to do with the host immune response, have been implicated in the susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B infection. The TNFSF9 gene encodes the CD137L protein, and its expression was found to be significantly higher in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection than in healthy controls. Its expression was also found to be higher in patients who had chronic hepatitis B with cirrhosis, in contrast to those without cirrhosis. [28]

Research done in West Africa, where 90% of the population is infected with hepatitis B, shows that certain human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II haplotypes influence the likelihood of chronic infection. For reasons that are not completely clear, patients in the study who were heterozygous for the HLA-DRA and HLA-DQA1 genes were found to be less likely to develop a chronic infection. [29]

IFNGR1 gene

Several additional genes are associated with susceptibility to hepatitis B infection. The IFNGR1 gene is located at 6q23.3 and encodes the interferon gamma (IFN-γ) receptor 1, which has an important role in cell-to-cell communications and can be activated in response to infection, but it is not specific to hepatitis B. [30] Patients with significant dysfunction in this gene have a particular immune deficiency that leaves them extremely susceptible to mycobacterial infections. [30]

A more subtle change in the promoter region at location -56 in this gene has shown significant association with the natural history of hepatitis B infection. Individuals with the C allele at this location were found in a study to be more likely to clear the virus, whereas individuals with the T allele at this location were more likely to have persistent viral infection. [31]

IFNAR2 gene

The IFNAR2 gene is located at 21q22.1 and encodes the IFN-alpha, -beta, and -omega receptor 2. Although it presumably is like the previous gene, with multiple functions in the immune system, at the present time it is known only to be associated with susceptibility to hepatitis B.

A study looking at this gene found that a single nucleotide polymorphism, resulting in a phenylalanine-to-serine substitution at position 8, was associated with an increased risk for chronic hepatitis B infection. [32]

IL1OR2 gene

The same study also found that a polymorphism in the IL10R2 gene (or the CRFB4 gene), also located at 21q22.11, is associated with an increased risk of chronic hepatitis B infection. This particular polymorphism results in a lysine-to-glutamic acid substitution at position 47. [32]

Variations in vaccine response

It is also known that certain patients have different responses to the hepatitis B vaccine. One study found that 14% of patients who received the vaccine were low responders. [33] A greater-than-expected number of these patients were homozygotes for the HLA-B8, -SC01, and -DR3 haplotypes. It was hypothesized that because HLA II binds antigens, different haplotypes may alter the way in which vaccine peptides activate the immune system. [33]

Another study, which looked at 914 immune candidates in over 1600 patients who were given the HBV vaccine, found numerous single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that were associated with inadequate levels of antibody response after vaccination, [34] with most found in the HLA genes.

However, one SNP was found in the 3 prime (3’) downstream region of the FOXP1 gene. This gene is a transcriptional repressor that plays a role in the differentiation of monocytes and the function of macrophages. [34]

Epidemiology

US statistics

Because of the implementation of routine vaccination of infants in 1992 and of adolescents in 1995, the prevalence of HBV infection has significantly declined in individuals born in the United States.

It is estimated that there are around 60,000 new cases annually. Two million or more people in the United States have chronic HBV infection; it is estimated that foreign-born persons from high endemic areas represent more than half of the total cases. [35] The prevalence of the disease is higher among Black individuals and persons of Hispanic or Asian origin.

HBV disease not only accounts for 5-10% of cases of chronic end-stage liver disease and 10-15% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States, it is also the dominant cause of cirrhosis and HCC worldwide.

HBV is responsible for at least 5000 US deaths annually. The prevalence is low in persons younger than 12 years born in the United States, with the subsequent increase being associated with the initiation of sexual contact (the major mode of transmission in adults, along with intravenous drug abuse [IVDA]). It is also associated with the occurrence of first intercourse at an early age. Additional risk factors, as identified in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III, are as follows:

- Non-Hispanic Black ethnicity

- Cocaine use

- High number of sexual partners

- Divorced or separated marital status

- Foreign birth

- Low educational level

International statistics

Globally, chronic HBV infection affects 250-350 million people, [34, 36] with disease prevalence varying among geographic regions, from 1-20%. A higher rate exists, for example, among Alaskan Eskimos, Asian Pacific islanders, Australian aborigines, and populations from the Indian subcontinent, sub-Saharan Africa, and Central Asia. In some locations, such as Vietnam, the rate is as high as 30%. Such variation is related to differences in the mode of transmission, including iatrogenic transmission, and the patient's age at infection.

Occult hepatitis B infection appears to have an overall prevalence of 4% in Asia (3% each in East and South Asia; 9% each in West and Souteast Asia) and is associated with disease progression. [37] There is a 1% prevalence of occult infection in the general population but a 5% prevalence in high-risk groups, 9% in HIV patients; and 18% in hepatopathy patients.

The lifetime risk of HBV infection is less than 20% in low prevalence areas (generally 0.1-2%), [10] and sexual transmission and percutaneous transmission during adulthood are the main modes through which it spreads. About 12% of HBV-infected individuals live in low-prevalence areas, which include the United States, Canada, western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. [10]

Sexual and percutaneous transmission and transmission during delivery are the major transmission routes in areas of intermediate prevalence (rate of 3-5%). These regions include Eastern and Northern Europe, Japan, the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East, Latin and South America, and Central Asia. One study reported approximately 43% of HBV-infected individuals live in South Central and West Asia, Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central and South America, with a prevalence rate of 2-7% and a lifetime HBV risk of 20-60%. [10]

In areas of high prevalence (≥8%, generally 10-20%), the predominant mode of transmission is perinatal, and the disease is transmitted vertically during early childhood from the mother to the infant. Approximately 45% of individuals infected with HBV live in high-prevalence areas, with a lifetime infection risk of over 60%, as demonstrated by the presence of hepatitis B core antibodies (anti-HBc) to hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) in serum. [10] Such regions include China, Southeast Asia, Indonesia, sub-Saharan Africa, Pacific Islands, parts of the Middle East, and the Amazon Basin.

Vaccination programs implemented in highly endemic areas seem to have reduced the prevalence of HBV infection. In Taiwan, for example, HBV seroprevalence declined from 10% in 1984 (before vaccination programs) to less than 1% in 1994 after the implementation of vaccination programs, and the incidence of HCC declined from 0.52% to 0.13% during the same period. [6]

The 10 genotypes of HBV (A-J) also correspond to specific geographic distributions. [22] Genotype A is more frequently found in North America, northwestern Europe, India, and Africa, whereas genotypes B and C are endemic to Asia, and genotype D predominates in Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. Type E is found in western Africa; type F, in South America; and type G, in France, Germany, Central America, Mexico, and the United States. Type H is prevalent in Central America [10] ; type I, in Vietnam; and type J, in Japan. [22]

Race-, sex-, and age-related demographics

In the United States, Black persons have a higher prevalence of HBV disease than do Hispanics or whites. In addition, more cases of chronic HBV disease occur in males than in females.

The earlier the disease is acquired, the greater the chance a patient has of developing chronic hepatitis B infection. Infants (mainly infected through vertical transmission) have a 90% chance, children have a 25-50% chance, adults have an approximately 5% chance, and elderly persons have an approximately 20-30% chance of developing chronic disease.

Prognosis

The prognosis of patients who contract hepatitis B depends on several factors. Those with an acute hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection may spontaneously clear the virus, while others may progress to chronic infection, ultimately leading to cirrhosis and to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the risk of which depends on the mode of infection, viral genotype, and presence of coinfection, among other factors. An estimated 1 million persons per year globally, including at least 5000 persons annually in the United States, die from chronic hepatitis B disease. [35]

Positive prognostic factors

Patients who have lost the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and in whom hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA is undetectable have an improved clinical outcome, as characterized by the following:

- Slower rate of disease progression

- Prolonged survival without complications

- Reduced rate of HCC and cirrhosis

- Clinical and biochemical improvement after decompensation

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Chronic hepatitis B infection is the major contributor to the development of approximately 50% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) worldwide. [38] Studies indicate that the level of hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA, which indicates viral replication, is a strong predictor for cirrhosis and HCC regardless of other viral factors. [38] Approximately 9% of patients in western Europe who have cirrhosis develop HCC due to hepatitis B infection at a mean follow-up of 73 months. The probability of HCC developing 5 years after the diagnosis of cirrhosis has been established at 6%, and the probability of decompensation is 23%.

Significant risk factors for carcinogenesis include the following:

- Older age

- Exposure to aflatoxins

- Alcohol

- Coinfection with HCV and HDV

- Immune status

- Genotype

- Core and precore mutations

- Cirrhosis

- Thrombocytopenia

High serum viral load (ie, viral replication) that is persistently elevated over time is the most reliable indicator in predicting the development of HCC. [39]

Even the presence of hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) in the absence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) or HBV DNA is significantly related to an increased risk for HCC, although there are no recommendations for HCC surveillance in such cases unless cirrhosis is present.

The annual incidence of HCC reported in Taiwan in patients with hepatitis B infection and cirrhosis is 2.8%. The US estimates for the annual incidence of HCC in patients infected with HBV is 818 cases per 100,000 persons.

Distinct mutations associated with different HBV genotypes have been linked to an increased risk of developing advanced fibrosis and HCC. Genotype C is closely associated with HCC; this appears to be related to a higher incidence of core and precore mutations in patients older than 50 years with cirrhosis and genotype C, [22] whereas genotype B is associated with HCC development in young, noncirrhotic patients and in postsurgical relapse. [39] Various international studies additionally demonstrated a greater association of genotypes C, D, and F with cirrhosis and HCC compared to genotypes A and B.

Mortality

Familial clustering of HCC has been described among families with hepatitis B infection in Africa, the Far East, and Alaska. The cumulative probability of survival is 84% at 5 years and 68% at 10 years.

Cox regression analysis has identified 6 variables that independently correlate with overall survival for individuals with cirrhosis or HCC. These include age, albumin level, platelet count, splenomegaly, bilirubin level, and positivity for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) at the time of the hepatitis B diagnosis. Based on the contribution of each of these factors to the final model, a prognostic index has been constructed that allows calculation of the estimated survival probability.

Expression of inflammatory molecules in HBV-related HCC tissues is associated with poor prognosis. [39] Imbalance between intratumoral CD8* T cells and regulatory T cells or type 1 helper T cells (Th1), and type 2 helper T-cell (Th2) cytokines in peritumoral tissues can predict the prognosis of HBV-related HCC. These molecules are also important for developing active prevention and surveillance of HBV-infected patients. [39]

Glomerulonephritis

The prognosis of renal disease in hepatitis B is related to several factors, such as age and the response to therapy. Children with membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) have a more favorable response than adults. White persons have a better response than Asian and Black patients.

Approximately 30-60% of cases with MGN undergo spontaneous remission. However, the course of HBV-related membranous nephropathy in adults in areas in which the virus is endemic is not benign. Regardless of treatment, hepatitis B disease has a slow, but relentlessly progressive, clinical course in approximately one third of patients, resulting in progressive renal failure and necessitating maintenance dialysis therapy.

Patient Education

Patients with acute and chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infections should be advised that this is a blood-borne disease that can be transmitted during sexual intercourse or at the time of childbirth. Prophylaxis is strongly advised. Family members borne by the same parents should also be checked for HBV infection. The best preventative measurement is vaccination. [1]

For patient education information, see Hepatitis A (HAV, Hep A); Hepatitis B (HBV, Hep B); Hepatitis C (HCV, Hep C); Cirrhosis of the Liver; Liver Cancer; Immunization Schedule, Adults; and Childhood Immunization Schedule and Chart.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B information for health professionals: hepatitis B FAQs for health professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/index.htm. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/index.htm. Updated May 31, 2015; Accessed: May 23, 2017.

- Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement: management of hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jan 20. 150(2):104-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Nguyen MH, Wong G, Gane E, Kao JH, Dusheiko G. Hepatitis B virus: advances in prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020 Mar 18. 33(2):e2128652. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- World Health Organization. Hepatitis B. July 27, 2021. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-b. Accessed: December 2, 2021.

- McMahon BJ, Holck P, Bulkow L, Snowball M. Serologic and clinical outcomes of 1536 Alaska Natives chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. Ann Intern Med. 2001 Nov 6. 135(9):759-68. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang MH, Chen CJ, Lai MS, et al. Universal hepatitis B vaccination in Taiwan and the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in children. Taiwan Childhood Hepatoma Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997 Jun 26. 336(26):1855-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fattovich G, Giustina G, Schalm SW, et al. Occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and decompensation in western European patients with cirrhosis type B. The EUROHEP Study Group on Hepatitis B Virus and Cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1995 Jan. 21(1):77-82. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yu MC, Yuan JM, Ross RK, Govindarajan S. Presence of antibodies to the hepatitis B surface antigen is associated with an excess risk for hepatocellular carcinoma among non-Asians in Los Angeles County, California. Hepatology. 1997 Jan. 25(1):226-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang HI, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, et al. Associations between hepatitis B virus genotype and mutants and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Aug 20. 100(16):1134-43. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Te HS, Jensen DM. Epidemiology of hepatitis B and C viruses: a global overview. Clin Liver Dis. 2010 Feb. 14(1):1-21, vii. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological record (WER): global routine vaccination coverage. 2011;86(46):509-20. Available at https://www.who.int/wer/2011/wer8646/en/index.html. Accessed: June 13, 2013.

- Blumberg BS. Australia antigen and the biology of hepatitis B. Science. 1977 Jul 1. 197(4298):17-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Norder H, Courouce AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994 Feb. 198(2):489-503. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lau JY, Wright TL. Molecular virology and pathogenesis of hepatitis B. Lancet. 1993 Nov 27. 342(8883):1335-40. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chisari FV, Ferrari C. Hepatitis B virus immunopathology. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1995. 17(2-3):261-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Davies SE, Portmann BC, O'Grady JG, et al. Hepatic histological findings after transplantation for chronic hepatitis B virus infection, including a unique pattern of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991 Jan. 13(1):150-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kahila Bar-Gal G, Kim MJ, Klein A, et al. Tracing hepatitis B virus to the 16th century in a Korean mummy. Hepatology. 2012 Nov. 56(5):1671-80. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gish RG, Locarnini S. Chronic hepatitis B viral infection. Yamada T, ed. Textbook of Gastroenterology. 5th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing; 2009. 2112-38.

- Azmi AN, Tan SS, Mohamed R. Practical approach in hepatitis B e antigen-negative individuals to identify treatment candidates. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 14. 20(34):12045-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Jung MC, Diepolder HM, Pape GR. T cell recognition of hepatitis B and C viral antigens. Eur J Clin Invest. 1994 Oct. 24(10):641-50. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chisari FV. Cytotoxic T cells and viral hepatitis. J Clin Invest. 1997 Apr 1. 99(7):1472-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Kuo A, Gish R. Chronic hepatitis B infection. Clin Liver Dis. 2012 May. 16(2):347-69. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tong W, He J, Sun L, He S, Qi Q. Hepatitis B virus with a proposed genotype I was found in Sichuan Province, China. J Med Virol. 2012 Jun. 84(6):866-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sonneveld MJ, Rijckborst V, Zeuzem S, et al. Presence of precore and core promoter mutants limits the probability of response to peginterferon in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2012 Jul. 56(1):67-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Fattovich G, Giustina G, Christensen E, et al. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (Eurohep). Gut. 2000 Mar. 46(3):420-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Wursthorn K, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H. Natural history: the importance of viral load, liver damage and HCC. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008. 22(6):1063-79. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Heidrich B, Serrano BC, Idilman R, et al. HBeAg-positive hepatitis delta: virological patterns and clinical long-term outcome. Liver Int. 2012 Oct. 32(9):1415-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wang J, Zhao W, Cheng L, et al. CD137-mediated pathogenesis from chronic hepatitis to hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis B virus-transgenic mice. J Immunol. 2010 Dec 15. 185(12):7654-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Thursz MR, Thomas HC, Greenwood BM, Hill AV. Heterozygote advantage for HLA class-II type in hepatitis B virus infection. Nat Genet. 1997 Sep. 17(1):11-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Jouanguy E, Lamhamedi-Cherradi S, Altare F, et al. Partial interferon-gamma receptor 1 deficiency in a child with tuberculoid bacillus Calmette-Guérin infection and a sibling with clinical tuberculosis. J Clin Invest. 1997 Dec 1. 100(11):2658-64. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Zhou J, Chen DQ, Poon VK, et al. A regulatory polymorphism in interferon-gamma receptor 1 promoter is associated with the susceptibility to chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Immunogenetics. 2009 Jun. 61(6):423-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Frodsham AJ, Zhang L, Dumpis U, et al. Class II cytokine receptor gene cluster is a major locus for hepatitis B persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006 Jun 13. 103(24):9148-53. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Alper CA, Kruskall MS, Marcus-Bagley D, et al. Genetic prediction of nonresponse to hepatitis B vaccine. N Engl J Med. 1989 Sep 14. 321(11):708-12. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Davila S, Froeling FE, Tan A, et al. New genetic associations detected in a host response study to hepatitis B vaccine. Genes Immun. 2010 Apr. 11(3):232-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Kowdley KV, Wang CC, Welch S, Roberts H, Brosgart CL. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B among foreign-born persons living in the United States by country of origin. Hepatology. 2012 Aug. 56(2):422-33. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tripathi N, Mousa OY. Hepatitis B. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021 Jul 18. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Xie WY, Sun C, He H, Deng C, Sheng Y. Estimates of the prevalence of occult HBV infection in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis (Lond). 2022 Dec. 54 (12):881-96. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kim BK, Han KH, Ahn SH. Prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Oncology. 2011. 81 Suppl 1:41-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Han YF, Zhao J, Ma LY, et al. Factors predicting occurrence and prognosis of hepatitis-B-virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2011 Oct 14. 17(38):4258-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Caputo R, Gelmetti C, Ermacora E, Gianni E, Silvestri A. Gianotti-Crosti syndrome: a retrospective analysis of 308 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992 Feb. 26(2 Pt 1):207-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Terrault NA, Bzowej NH, Chang KM, et al, for the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. AASLD guidelines for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2016 Jan. 63(1):261-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Arora S, Martin CL, Herbert M. Myth: interpretation of a single ammonia level in patients with chronic liver disease can confirm or rule out hepatic encephalopathy. CJEM. 2006 Nov. 8(6):433-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines. Viral hepatitis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/hepatitis.htm. June 4, 2015; Accessed: May 26, 2017.

- Finnish Medical Society Duodecim. Viral hepatitis. EBM Guidelines. Evidence-Based Medicine [Internet]. Helsinki, Finland: Wiley Interscience; 2008.

- New York State Department of Health. Hepatitis B virus. New York, NY: New York State Department of Health; 2008. Available at https://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=12812. Accessed: June 13, 2013.

- [Guideline] U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: screening. December 15, 2020. Available at https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/hepatitis-b-virus-infection-screening. Accessed: December 2, 2021.

- Barclay L. USPSTF shifts course, favors hepatitis B screening. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/825948. May 30, 2014; Accessed: June 2, 2014.

- LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in nonpregnant adolescents and adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jul 1. 161(1):58-66. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chou R, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Khangura J, Zakher B. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in adolescents and adults: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jul 1. 161(1):31-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Rajbhandari R, Chung RT. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection: a public health imperative. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Jul 1. 161(1):76-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Eckman MH, Kaiser TE, Sherman KE. The cost-effectiveness of screening for chronic hepatitis B infection in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2011 Jun. 52(11):1294-306. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018 Apr. 67 (4):1560-99. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Testing recommendations for hepatitis C virus infection. July 29, 2020. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/hcv/guidelinesc.htm. Accessed: December 2, 2021.

- Trinchet JC, Chaffaut C, Bourcier V, et al. Ultrasonographic surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis: a randomized trial comparing 3- and 6-month periodicities. Hepatology. 2011 Dec. 54(6):1987-97. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- US Food and Drug Administration. 510(k) Premarket notification: Hepatiq. Available at https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfpmn/pmn.cfm?ID=K142891. Accessed: January 11, 2015.

- Business Wire. FDA clears Hepatiq [press release]. Hepatiq: Hepatic Quantitation. Available at https://www.hepatiq.com/fdaclearshepatiq.html. Accessed: January 11, 2015.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. HALT-C (Hepatitis C Antiviral Long-term Treatment against Cirrhosis) trial website. Available at https://archives.niddk.nih.gov/haltctrial/displaypage.aspx?pagename=haltctrial/index.htm. Accessed: January 11, 2015.

- Srinivasa Babu A, Wells ML, Teytelboym OM, et al. Elastography in chronic liver disease: modalities, techniques, limitations, and future directions. Radiographics. 2016 Nov-Dec. 36(7):1987-2006. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] World Health Organization. Guidelines for the prevention, care and treatment of persons with chronic hepatitis B infection. Geneva, Switzerland; WHO. 2015 Mar. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Nebbia G, Peppa D, Maini MK. Hepatitis B infection: current concepts and future challenges. QJM. 2012 Feb. 105(2):109-13. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009 Sep. 50(3):661-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Papatheodoridis G, Buti M, Cornberg M, et al, for the European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012 Jul. 57(1):167-85. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Liaw YF, Leung N, Kao JH, et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2008 update. Hepatol Int. 2008 Sep. 2(3):263-83. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Sherman M, Shafran S, Burak K, et al. Management of chronic hepatitis B: consensus guidelines. Can J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jun. 21 Suppl C:5C-24C. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- [Guideline] Kennedy PT, Lee HC, Jeyalingam L, et al. NICE guidelines and a treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B: a review of 12 years experience in west London. Antivir Ther. 2008. 13(8):1067-76. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: an update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006 Aug. 4(8):936-62. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- New York State Department of Health. Prevention of secondary disease: preventive medicine. Viral hepatitis. New York, NY: New York State Department of Health; 2010. Available at https://guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=24043. Accessed: June 13, 2013.

- Pharmasset voluntarily halts clinical studies with clevudine in hepatitis B infected patients. Medical News Today. Available at https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/releases/146749.php. April 21, 2009; Accessed: June 13, 2013.

- Mutimer D, Naoumov N, Honkoop P, et al. Combination alpha-interferon and lamivudine therapy for alpha-interferon-resistant chronic hepatitis B infection: results of a pilot study. J Hepatol. 1998 Jun. 28(6):923-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gara N, Zhao X, Collins MT, et al. Renal tubular dysfunction during long-term adefovir or tenofovir therapy in chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Jun. 35(11):1317-25. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Lange CM, Bojunga J, Hofmann WP, et al. Severe lactic acidosis during treatment of chronic hepatitis B with entecavir in patients with impaired liver function. Hepatology. 2009 Dec. 50(6):2001-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Wong DK, Cheung AM, O'Rourke K, Naylor CD, Detsky AS, Heathcote J. Effect of alpha-interferon treatment in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. A meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Aug 15. 119(4):312-23. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tseng TC, Liu CJ, Su TH, et al. Serum hepatitis B surface antigen levels predict surface antigen loss in hepatitis B e antigen seroconverters. Gastroenterology. 2011 Aug. 141(2):517-25, 525.e1-2. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yi Z, Jie YW, Nan Z. The efficacy of anti-viral therapy on hepatitis B virus-associated glomerulonephritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Hepatol. 2011 Apr-Jun. 10(2):165-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Guillevin L, Mahr A, Cohen P, et al. Short-term corticosteroids then lamivudine and plasma exchanges to treat hepatitis B virus-related polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Jun 15. 51(3):482-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lau GK, Piratvisuth T, Luo KX, et al. Peginterferon Alfa-2a, lamivudine, and the combination for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 30. 352(26):2682-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marcellin P, Lau GK, Bonino F, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a alone, lamivudine alone, and the two in combination in patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2004 Sep 16. 351(12):1206-17. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tenney DJ, Pokornowski KA, Rose RE, et al. Entecavir maintains a high genetic barrier to HBV resistance through 6 years in naive patients [abstract]. J Hepatol. 2009. 50(Suppl 1):S10.

- Wong GL, Wong VW, Chan HY, et al. Undetectable HBV DNA at month 12 of entecavir treatment predicts maintained viral suppression and HBeAg-seroconversion in chronic hepatitis B patients at 3 years. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012 Jun. 35(11):1326-35. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006 Mar 9. 354(10):1001-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang TT, Lai CL, Kew Yoon S, et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010 Feb. 51(2):422-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schiff ER, Lee SS, Chao YC, et al. Long-term treatment with entecavir induces reversal of advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Mar. 9(3):274-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Schnittman SM, Pierce PF. Potential role of lamivudine (3TC) in the clearance of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in a patient coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus type. Clin Infect Dis. 1996 Sep. 23(3):638-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999 Oct 21. 341(17):1256-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Grellier L, Mutimer D, Ahmed M, et al. Lamivudine prophylaxis against reinfection in liver transplantation for hepatitis B cirrhosis. Lancet. 1996 Nov 2. 348(9036):1212-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Gatanaga H, Hayashida T, Tanuma J, Oka S. Prophylactic effect of antiretroviral therapy on hepatitis B virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Jun. 56(12):1812-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tipples GA, Ma MM, Fischer KP, Bain VG, Kneteman NM, Tyrrell DL. Mutation in HBV RNA-dependent DNA polymerase confers resistance to lamivudine in vivo. Hepatology. 1996 Sep. 24(3):714-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Honkoop P, Niesters HG, de Man RA, Osterhaus AD, Schalm SW. Lamivudine resistance in immunocompetent chronic hepatitis B. Incidence and patterns. J Hepatol. 1997 Jun. 26(6):1393-5. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marcellin P, Chang TT, Lim SG, et al. Adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2003 Feb 27. 348(9):808-16. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2005 Jun 30. 352(26):2673-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Yang H, Westland CE, Delaney WE 4th, et al. Resistance surveillance in chronic hepatitis B patients treated with adefovir dipivoxil for up to 60 weeks. Hepatology. 2002 Aug. 36(2):464-73. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Villeneuve JP, Durantel D, Durantel S, et al. Selection of a hepatitis B virus strain resistant to adefovir in a liver transplantation patient. J Hepatol. 2003 Dec. 39(6):1085-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Angus P, Vaughan R, Xiong S, et al. Resistance to adefovir dipivoxil therapy associated with the selection of a novel mutation in the HBV polymerase. Gastroenterology. 2003 Aug. 125(2):292-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Chang TT, Lai CL. Hepatitis B virus with primary resistance to adefovir. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jul 20. 355(3):322-3; author reply 323. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Hill A, Hughes SL, Gotham D, Pozniak AL. Tenofovir alafenamide versus tenofovir disoproxil fumarate: is there a true difference in efficacy and safety?. J Virus Erad. 2018 Apr 1. 4(2):72-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Heathcote J, George J, Gordon S, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for the treatment of HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B: week 72 TDF data and week 24 adefovir dipivoxil switch data (study 103) [abstract]. J Hepatol. 2008. 48(suppl 2):S32.

- Marcellin P, Jacobson I, Habersetzer F, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) for the treatment of HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B: week 72 TDF data and week 24 adefovir dipivoxil switch data (study 102) [abstract]. J Hepatol. 2008. 48(suppl 2):S26.

- Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 4. 359(23):2442-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 86: Viral hepatitis in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Oct. 110(4):941-56. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jun 16. 150(12):869-73, W154. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] World Health Organization. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus: guidelines on antiviral prophylaxis in pregnancy. Geneva, Switzerland. 2020 Jul. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Eke AC, Brooks KM, Gebreyohannes RD, Sheffield JS, Dooley KE, Mirochnick M. Tenofovir alafenamide use in pregnant and lactating women living with HIV. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2020 Apr. 16(4):333-42. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lin CL, Kao JH. Hepatitis B: immunization and impact on natural history and cancer incidence. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2020 Jun. 49(2):201-14. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Vesikari T, Finn A, van Damme P, et al, for the CONSTANT Study Group. Immunogenicity and safety of a 3-antigen hepatitis B vaccine vs a single-antigen hepatitis B vaccine: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021 Oct 1. 4(10):e2128652. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Vesikari T, Langley JM, Segall N, et al, for the PROTECT Study Group. Immunogenicity and safety of a tri-antigenic versus a mono-antigenic hepatitis B vaccine in adults (PROTECT): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Sep. 21(9):1271-81. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Terrault NA, Lok ASF, McMahon BJ, et al. Update on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: AASLD 2018 hepatitis B guidance. Hepatology. 2018 Apr. 67(4):1560-99. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Heplisav-B (hepatitis B vaccine [recombinant], adjuvanted) [package insert]. Berkeley, CA: Dynavax Technologies, Corp. November, 2017. Available at [Full Text].

- Malarkey MA, Gruber MF. Biologics License Application (BLA) approval (BL 125428) (hepatitis B vaccine (recombinant), adjuvanted [Heplisav-B]). US Food and Drug Administration. Available at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm584820.pdf. November 9, 2017; Accessed: November 13, 2017.

- Weir J. Biologics License Application (BLA) (BL 125428/1) supplement approval (hepatitis B vaccine (recombinant), adjuvanted [Heplisav-B]). US Food and Drug Administration. Available at https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM602537.pdf. March 22, 2018; Accessed: April 20, 2018.

- [Guideline] Schillie S, Harris A, Link-Gelles R, Romero J, Ward J, Nelson N. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices for use of a hepatitis B vaccine with a novel adjuvant. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018 Apr 20. 67 (15):455-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Dec 23. 60(50):1709-11. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Kakisaka K, Sakai A, Yoshida Y, et al. Hepatitis B surface antibody titers at one and two years after hepatitis B virus vaccination in healthy young Japanese adults. Intern Med. 2019 Aug 15. 58(16):2349-55. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Juday T, Tang H, Harris M, Powers AZ, Kim E, Hanna GJ. Adherence to chronic hepatitis B treatment guideline recommendations for laboratory monitoring of patients who are not receiving antiviral treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Mar. 26(3):239-44. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- El-Serag HB, Davila JA. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: in whom and how?. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011 Jan. 4(1):5-10. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hoofnagle JH. Reactivation of hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2009 May. 49(5 suppl):S156-65. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Hagiyama H, Kubota T, Komano Y, Kurosaki M, Watanabe M, Miyasaka N. Fulminant hepatitis in an asymptomatic chronic carrier of hepatitis B virus mutant after withdrawal of low-dose methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004 May-Jun. 22(3):375-6. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Narvaez J, Rodriguez-Moreno J, Martinez-Aguila MD, Clavaguera MT. Severe hepatitis linked to B virus infection after withdrawal of low dose methotrexate therapy. J Rheumatol. 1998 Oct. 25(10):2037-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Markovic S, Drozina G, Vovk M, Fidler-Jenko M. Reactivation of hepatitis B but not hepatitis C in patients with malignant lymphoma and immunosuppressive therapy. A prospective study in 305 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999 Sep-Oct. 46(29):2925-30. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Sheen IS, Liaw YF, Lin SM, Chu CM. Severe clinical rebound upon withdrawal of corticosteroid before interferon therapy: incidence and risk factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996 Feb. 11(2):143-7. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Navarro R, Vilarrasa E, Herranz P, et al. Safety and effectiveness of ustekinumab and antitumour necrosis factor therapy in patients with psoriasis and chronic viral hepatitis B or C: a retrospective, multicentre study in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Mar. 168(3):609-16. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Germanidis G, Hytiroglou P, Zakalka M, Settas L. Reactivation of occult hepatitis B virus infection, following treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis with abatacept. J Hepatol. 2012 Jun. 56(6):1420-1. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL 2017 clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2017 Aug. 67 (2):370-98. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Abara WE, Qaseem A, Schillie S, McMahon BJ, Harris AM, for the High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hepatitis B vaccination, screening, and linkage to care: best practice advice from the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Dec 5. 167 (11):794-804. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Phillips D. Clinical guideline on HBV released by ACP, CDC. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/888975. November 21, 2017; Accessed: January 16, 2018.

- [Guideline] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018 Aug. 69 (2):406-60. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018 Jul. 69 (1):182-236. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Gordan JD, Kennedy EB, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Systemic therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2020 Dec 20. 38(36):4317-45. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- CDC. Viral hepatitis surveillance report 2018 — hepatitis B. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2018surveillance/HepB.htm. 2020 July 27; Accessed: Acessed: October 26, 2020.

- Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012 Aug 17. 61:1-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Chou R, Cottrell EB, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: a systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2013 Jan 15. 158(2):101-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF, et al. Telbivudine (LdT) vs. lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B: first-year results from the international phase III GLOBE trial [abstract]. Hepatology. 2005. 42:748A.

- Liaw YF, Gane E, Leung N, et al. 2-Year GLOBE trial results: telbivudine Is superior to lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2009 Feb. 136(2):486-95. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Behre U, Bleckmann G, Crasta PD, et al. Long-term anti-HBs antibody persistence and immune memory in children and adolescents who received routine childhood hepatitis B vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012 Jun. 8(6):813-8. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- [Guideline] Chustecka Z. Boxed warning on HBV reactivation for blood cancer drugs. Medscape Medical News. Available at https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/811629. September 25, 2013; Accessed: October 2, 2013.

- [Guideline] FDA. Arzerra (ofatumumab) and Rituxan (rituximab): drug safety communication - new boxed warning, recommendations to decrease risk of hepatitis B reactivation. US Food and Drug Administration. Available at https://www.fda.gov/safety/medwatch/safetyinformation/safetyalertsforhumanmedicalproducts/ucm369846.htm. September 25, 2013; Accessed: October 2, 2013.

- Hadziyannis SJ, Tassopoulos NC, Heathcote EJ, et al. Long-term therapy with adefovir dipivoxil for HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B for up to 5 years. Gastroenterology. 2006 Dec. 131(6):1743-51. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013 Feb 9. 381(9865):468-75. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Purcell RH. The discovery of the hepatitis viruses. Gastroenterology. 1993 Apr. 104(4):955-63. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Tang KH, Yusoff K, Tan WS. Display of hepatitis B virus PreS1 peptide on bacteriophage T7 and its potential in gene delivery into HepG2 cells. J Virol Methods. 2009 Aug. 159(2):194-9. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Thibault V, Laperche S, Akhavan S, Servant-Delmas A, Belkhiri D, Roque-Afonso AM. Impact of hepatitis B virus genotypes and surface antigen variants on the performance of HBV real time PCR quantification. J Virol Methods. 2009 Aug. 159(2):265-70. [QxMD MEDLINE Link].

- Dan C. FDA approves Vemlidy (tenofovir alafenamide) for chronic hepatitis B in adults. US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at https://www.hhs.gov/hepatitis/blog/2016/11/21/fda-approves-vemlidy-tenofovir-alafenamide-for-chronic-hepatitis-b-in-adults.html. November 21, 2016; Accessed: May 23, 2017.

- US Food and Drug Administration. For patients: hepatitis B and C treatments. Available at https://www.fda.gov/forpatients/illness/hepatitisbc/ucm408658.htm. Updated: January 31, 2017; Accessed: May 23, 2017.

- Gilead Sciences, Inc. US Food and Drug Administration approves Gilead’s Vemlidy (tenofovir alafenamide) for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B virus infection [press release]. Available at https://www.gilead.com/news/press-releases/2016/11/us-food-and-drug-administration-approves-gileads-vemlidy-tenofovir-alafenamide-for-the-treatment-of-chronic-hepatitis-b-virus-infection. November 10, 2017; Accessed: May 23, 2017.

- Zhao Q, Liu K, Zhu X, et al. Anti-viral effect in chronic hepatitis B patients with normal or mildly elevated alanine aminotransferase. Antiviral Res. 2020 Oct 13. 184:104953. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Tripathi N, Mousa OY. Hepatitis B. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Jan. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Phillips S, Jagatia R, Chokshi S. Novel therapeutic strategies for chronic hepatitis B. Virulence. 2022 Dec. 13 (1):1111-32. [QxMD MEDLINE Link]. [Full Text].

- Wodi PA, Issa AN, Moser CA, Cineas S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Adults Aged 19 Years or Older — United States, 2025. MMWR. January 16, 2025. 74(2):30-33. [Full Text].

- Issa AN, Wodi AP, Moser CA, Cineas S. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Recommended Immunization Schedule for Children and Adolescents Aged 18 Years or Younger — United States, 2025. MMWR. January 16, 2025. 74(2):27-29. [Full Text].

- Hepatitis B. Under higher-power magnification, ground-glass cells may be visible in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Ground-glass cells are present in 50% to 75% of livers with chronic HBV infection. Immunohistochemical staining is positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg.)