Pulp Venus by Den Valdron (original) (raw)

PULP VENUS

All righty. If you�re reading this, then that means that you�ve probably read my other articles on the Venus of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Ralph Milne Farley and Otis Adelbert Kline, and are dumbly plodding through to just get it all finished.

If you haven�t read those articles, then I�m not sure why you are reading this at all. But what the hell, welcome aboard. It's as good a place as any to start.

Burroughs, Farley and Kline all wrote fundamentally similar versions of Venus. In this, they were not copying from each other, but rather, all of them were working off the same ideas and images of what Venus might be like. This was the Venus of the pulps, not a wholely fictional invention, but rather, one couched in the science of the age and in the social beliefs of the time between 1890 and 1940.

What was that Venus? Well, let�s start with the basic science of the day. The astronomers of that period could look through their telescopes, take observations, make calculations, apply Newtonian physics and come up with some very basic information:

- Venus was about 70 million miles from the sun, it was Earth�s closest neighbor in the solar system. Given its greater proximity to the sun, it was believed to be a hotter or warmer planet than Earth.

- Venus was about the same size as Earth, with about 90% of Earth�s diameter and mass. The mass and gravity of Venus could be calculated by its effects on the orbits of other worlds, and their effects on it.

- Venus was completely swathed in clouds, its surface was never visible. Thus, the cautious scientist could draw no conclusion as to what lay beneath those clouds.

- On the other hand, some guesses could be made about what those clouds were. On Earth, clouds are made up of water vapour or droplets. So this was likely the case for Venus. Early spectroscope readings seemed to confirm this when they found both water and oxygen in Venus� atmosphere (actually, they were just reading the water and oxygen in Earth�s atmosphere as they were looking at Venus). Since the clouds were so extensive, Venus was presumed to be an extremely wet planet, a lot wetter than Earth.

- It�s year was 225 days, but its day was indeterminate, since you couldn�t see the surface and measure rotation.

And that�s basically what the state of science for Venus was. They got some things right, they got some things wrong, but even the wrong guesses were relatively reasonable for the time.

Now, to this we can add a little bit more science, watching carefully as it shades into the social prejudices of the day. One of the central notions of the time was that planets had �life histories� and that they aged over time.

Consider the moon. Anyone could look up at the moon and sea the flat sea beds of the lunar maria. One could look through the telescopes of the time and see the heavily cratered �lands� and the smooth areas of the �seas.� But it was clear that the moon was a dead world. Still, the smooth craterless maria or seas proved that once upon a time, it must have had real seas and therefore a real atmosphere. It had lost these.

The physics of the time could isolate and weight gases and molecules, and they could calculate that at different gravities, molecules of atmosphere would inevitably be lost to space. There was the answer. The moon had lost its atmosphere over time, due to its reduced gravity.

Earth, with a heavier gravity retained more atmosphere. But of course, ultimately, it was a question of time. The Earth might sooner or later find its atmosphere fading away and eventually would end up like the moon.

But where did the atmosphere come from in the first place? Ahhh, scientists said. When worlds are born, they are born with atmospheres, or create them through the outgassing of Volcanoes.

Now this lead to some fairly interesting ideas that were somewhat inter-related. It was all about heat and age.

Where did planets come from? Well, either they were all created at the same time, with the birth of the solar system, something called the Catastrophic Hypothesis, which held that the planets were the leftovers of a collision between the sun and some vast stellar body. Or they were spit out by the sun, by some unknown process.

The great rival to the Catastrophic Hypothesis was called the Nebular Hypothesis. First suggested by Immanuel Kant in 1775 and then elaborated by Laplace in 1796, the idea here was that the planets had coalesced out of a great belt of dust and gas surrounding the sun. The outer planets had coalesced first, and the inner ones successively later.

Either way, the outermost planets were older, the middle planets were younger and the inner planets were youngest of all. Thus, Mars was older than Earth and Earth was older than Venus.

And there were a couple of other things operating. The planets all had internal heat. Earth was hot, we knew that from Volcanoes, and Earth received heat from the sun. Venus was closer to the sun than Earth, so it got more heat, and being slightly younger, it probably retained more internal heat.

Poor old Mars, on the other hand, was further from the sun, received less heat, was older and thus its heat had dissipated over a longer time, and it was smaller than either Earth or Venus, which meant that its heat dissipated more quickly.

The Moon was so much smaller that all its internal heat had dissipated millions of years ago. Without internal heat and volcanoes to replenish its constantly thinning atmosphere... well, that was all she wrote. If went cold, its remaining atmosphere boiled into space, and it became a dead world.

Mars, in size somewhere between the Earth and the Moon, was an older world. It still held onto an atmosphere, but its internal heat was diminishing, its volcanoes dying, the atmosphere was thinning, its oceans drying or dried.

So this was the state of science at the time, and if they got a few things wrong or seem simplistic, well, we can�t hold it against them too much. After all, they didn�t have space probes or radio telescopes, they didn�t have Einsteinian physics to answer questions. They were men working with crude and limited instruments, doing calculations without the aid of calculators and computers. It�s remarkable who good their studies were, and their errors are forgiveable.

But anyway, this lead to a couple of social ideas that, if scientists were not prepared to endorse, they were in little position to criticize.

The notion that there might be a planetary �life cycle� made it into the popular culture as an actual life cycle. That is, plants, animals and humans were born, grew up, matured, aged and then died.

From this, there had been a victorian notion that such life cycles could apply to entire species, races and even to life.

Thus, Earth�s history was a progression, life was born, it grew and matured and resulted in us. Previous editions of life, like the dinosaurs, were an earlier and immature period. Dinosaurs were primitive, with tiny brains. We were advanced. Evolution moved ever onwards and upwards.

Cultures like those of the Africans or Native Americans were seen as infant and childlike cultures, and African and Native American people, for this reason, were seen as dependent childlike beings, in need of the firm guiding hand of civilization. Thus, the �White Man�s Burden.�

Other cultures, such as the Muslim World or China, who had been civilized a lot longer than we were, were still unable to withstand Western power. In our view, these cultures had aged. Once clearly, they had been strong and vital, the history books showed that in no uncertain terms. But they had lost their edge, they had become old, weak, decadent.

Europe and America, as we self absorbedly congratulated ourselves, were the happy middle. We weren�t old and decadent like China and Islam, and we weren�t young and unformed like Africa. Instead, we were in the prime of maturity, and thus entitled to rule the world.

There was a sort of notion of predestination, nature had been labouring for billions of years to produce us, its inescapable and inevitable product.

So it made a certain amount of sense that a planet, and life on that planet would have the same sort of cycle. Thus, worlds were born, matured, aged and died. The evidence was obviously littering the solar system. There was a vital world in its prime, Earth, an aging world past its prime, Mars, a dead world, the Moon.

So of course, there had to be a �Young� world just starting out: Venus. And of course, there were Victorian ideas of symmetry at work. Earth was the happy medium. The old world Mars, was on one side. So it just made sense that the young world would be on the opposite side of us. Young, Mature, Old.

Now this may seem arbitrary and silly, but the Victorians had ideas like this because ultimately, they saw these sorts of symmetries as proof of the handiwork of God, or of a divinely ordained universe.

Remember the idea of predestination, the notion that all of natural history from dinosaurs on had inevitably worked to produce the human being and particularly the English Gentleman as the pinnacle of creation.

Well, if you really believed in that sort of inevitability, that evolution would proceed upwards and onwards until it produced a human, or something as close as it could get, then obviously, that would apply on other planets, wouldn�t it? Evolution was a law of nature, it would inevitably apply no matter where it was. After all, evolution occurred in Africa and Europe in the same way. So why not on Mars and Venus.

So, to these post-Victorians, to the people of the era, when they bothered to think about it, it only made sense that if you had an Earthlike world, with an atmosphere and oceans and in the right temperature range.... Well, of course it had to develop life! That only made sense!

And in fact, we still carry this notion with us today. The difference is that we are considerably more uncertain about things, because we really have no idea how life comes about. That�s why we want to go to Mars and look for it.

Of course, the people of this �pulp� era went a little further than we did. They figured that Evolution had to proceed along the same course. Thus, there would be an age of fish, an age of giant reptile monsters, an age of giant mammal monsters, and then you�d get to the modern ages and the result would have to be human or something very close to it. An English Gentleman was unique, but that didn�t mean that evolution wouldn�t strive.

Of course, there were scientists of the day who saw this for nonsense. Percival Lowell wrote that we were essentially flukes, and that an intelligent race might arise in any form or from any source. But that made little headway against the self satisfaction of the ruling culture.

America and Europe ruled the world, and we believed it was because we deserved to rule, we�d been chosen to rule, that the entire history of the world had been working its way up to us. We weren�t flukes. We were the chosen.

So these were the sorts of ideas and notions floating around in popular consciousness at the time, that writers had to draw upon, when they thought about what might lie on Venus.

Now, into this mixture, I�ll add one more element: Mars.

Now, the thing with Venus was that it was wrapped in clouds, an essentially blank slate. We couldn�t really guess blindly at what was going on under those clouds. But we knew Earth, and we thought we knew Mars.

Mars was a world whose surface we could actually see. We could look at the dry surface, the remains of continents, whispy clouds, and polar caps that swelled and shrank. We could see canals. A very extensive, very definite �story� of Mars. There was a narrative that had seeped into public consciousness through astronomers like Schiaparelli and Pervical Lowell, picked up by writers like H.G. Wells and Burroughs.

The narrative was that Mars not only had life, but it had people, that it was now a world in its sunset, its oceans drying up, its continents wearing down, deserts spreading everywhere. And on this world, people of some sort, were trying to prolongue existence by building canals, which meant that there was a civilization.

So, we had a narrative for Mars, we had narratives for Earth, and Venus was a blank slate. It was the cloud covered Earthlike world, hotter than our world, wetter than our world, younger than our world. Venus was the reversed mirror image of Mars, it was the other side from us of Mars.

So what this gave us the idea of a wet, warm Venus with vast seas and oceans, islands and marshes. It was a world full of moist clouds, which meant steady rains.

And, being a younger world, life would be younger. Venus was probably still in its age of dinosaurs or giant mammals. It would still have cave men or primitive ape men. So, Venus was probably chock full of prehistoric giant monsters, possibly not exactly the ones you would see on Earth. But creatures somewhat like them, so you�d get giant reptiles, giant ants or spiders, primitive elephantine brutes. You�d have gigantic fish and whales threatening shipping, huge flying pterodacyls or raptors, and no shortage of savage primeval killers. All of them stalking through primitive brutal jungles.

This image of Venus was not confined merely to pulp writers and adventure stories. Very sensible people took this seriously. As late as 1918, the Swedish chemist and Nobel laureate Svante Arrhenius wrote:

�Everything on Venus is dripping wet.... A very great part of the surface ... is no doubt covered with swamps corresponding to those on the Earth in which the coal deposits were formed.... The constantly uniform climatic conditions which exist everywhere result in an entire absence of adaptation to changing exterior conditions. Only low forms of life are therefore represented, mostly no doubt, belonging to the vegetable kingdom; and the organisms are nearly of the same kind all over the planet.�

Of course, two years later the first accurate spectroscope readings would show that there was no moisture at all in Venus� clouds and that the planet was as dry as a bone. But by then, the vision of Venus was too firmly rooted to dislodge. Most people, and scientists, didn�t pay attention, and writers, if they were bothered by it at all, simply assumed double or triple layers of cloud cover (the uppermost layer being dry and misleading spectroscopes).

Civilization on Venus was more primitive, almost oriental in character. If Martian civilization was desert and touched by images of Islam, then the lush wet Venus would be touched by images of Thai or Indonesian, Indian or Chinese culture. Really, at that point, Europe and the West really acknowledged only three or four great civilizations: Itself, Islam and the Orient.

Obviously, a dying decadent world would have an old decadent civilization, as Islam and China were seen to be now. But a younger evolving world wouldn�t have a European civilization yet. Rather, it would have something closer to the lush oriental civilization of the dawn of man.

And of course, there�s a final wrinkle that would show up. Mars was obviously the planet of war, named for the God of war. Venus was probably a lot nicer. It was a richer, younger more bountiful world than ancient, dried up old Mars. So, if you�re going to meet a friendly, enlightened, angelic race, they�re probably over on Venus.

That didn�t jibe so well with the notion of a savage primitive jungle world... Or did it? Wasn�t the idea of a primeval earlier version of Earth also a harkening back to the garden of Eden. In the confused mixture of science, self-satisfaction, religion and fate that made up the social construct or narrative that was the pulp Venus, angels and dinosaurs could easily co-exist.

In Apocryphal Barsooms, I charted out a great many early writers who had written versions of Mars which were similar to or could be fit into Barsoom.

It�s harder to do that with Venus. With Barsoom, there�s a lively literary tradition of crossovers, and a number of famous Mars novels by people like H.G. Wells, Otis Adelbert Kline, Michael Moorcock, C.S.Lewis and Matthew Arnold that you can add to the mix, as well as more obscure works which have not been connected to Burroughs in one way or the other.

With Venus, there�s no tradition of crossovers, and only two authors, Otis Adelbert Kline and Ralph Milne Farley, who can be said to have any kind of intersection with Burroughs. By the same token, there are simply fewer writers between 1890 and 1940, the pulp era, who actually wrote Venus stories (although it is worth noting that the vision of the jungle Venus of the pulps persisted a bit longer than Mars did. This Venus remained a fiction staple until the 1960's).

Of the early contemporary stories, most of them are lost or hard to find. We know, for instance, that Gustavus Pope who wrote Journey to Mars also wrote Journey to Venus.

So, for the most part, we�ll have to console ourselves with examining two works. George Griffiths visit to Venus in_Honeymoon in Space_, which is basically a repeat of some passages from Apocryphal Barsooms, and Columbus in Space.

HONEYMOON IN SPACE, GEORGE GRIFFITHS, 1901

Griffiths was one of the major science fiction writers of his day, a contemporary of H.G. Wells who sometimes outsold Wells himself. Unfortunately, Griffiths has not aged as well. This is largely because despite some very clever extrapolation, Griffiths somehow managed to avoid being exciting and lively like Burroughs, nor philosophical like Wells. Rather, his science fiction reaks of complacency and the established values of his day, some of which desperately needed examination.

One of his major works was called Honeymoon in Space. An English lord builds or obtains a working anti-gravity spaceship and takes his wife on a tour of the solar system. They walk among the ruins of a dead civilization on the moon, visit the warlike Martians and slaughter hundreds of them, they stop off at Venus and eventually travel out to the moons of Jupiter, meeting a friendly human civilization out there.\

The excursion to Venus has them meeting angelic winged beings with musical voices. Venus they discover is a primeval garden of eden. Eventually, after spending happy times there, they realize that they are in danger of corrupting the pure Venusian angels and take off. Or perhaps the lord�s wife wants to ride the pink bronco and she doesn�t want to startle the feathered people.

Not much of substance happens, but then, this is typical of the interplanetary adventures. Not much of substance happens on any planet they visit. They�re pretty much tourists all the way, and many of their dangerous situations are contrived or self inflicted.

I�ve discussed Honeymoon in Space in Apocryphal Barsooms, based on the trip to Mars. But since Venus is also featured prominently, I�ve decided to reproduce some of my comments.

Perhaps the best case for placing _Honeymoon in Space_in Burroughs universe comes not from Mars, but from Venus. Alighting on some random region of Venus, they encounter a race of Bird people. Allow me to contrast their observations with Burroughs descriptions:

".... yet they haven't got feathers." "Yes, they have, at least round the edges of their wings or whatever they are-- "You're quite right. Those fringes down their legs are feathers, and that's how they fly. They seem to have four arms." In some respects they had a sufficient resemblance to human form for them to be taken for winged men and women, while in another they bore a decided resemblance to birds. Their bodies and limbs were almost human in shape, but of slenderer and lighter build; and from the shoulder-blades and muscles of the back there sprang a pair of wings arching up above their heads. Between these and the lower arms, and continued from them down the sides to the ankles, there appeared to be a flexible membrane covered with a light feathery down, pure white on the inside, but on the back a brilliant golden yellow, deepening to bronze towards the edges, round which ran a deep feathery fringe." (Griffith)

"Their chests were large and shaped like those of birds. Their wings, which consist of a very thin membrane supported on a light framework, are similar in shape to those of a bat and do not appear adequate to the support of the apparent weight of the creatures' bodies, but I was to learn later that this apparent weight is deceptive, since their bones, like the bones of true birds, are hollow." (Burroughs)

"Below this and attached to the inner sides of the leg from the knee downward, was another membrane which reached down to the heels, and it was this which Redgrave somewhat flippantly alluded to as a tail. Its obvious purpose was to maintain the longitudinal balance when flying." (Griffith)

"Similar feathers also grow at the lower extremity of the torso in front, and there is another, quite large bunch just above the buttocks--a gorgeous tail which they open into a huge pompon when they wish to show off." (Burroughs)

Zaidie. "And look what funny little faces they've got! Half bird, half human, and soft, downy feathers instead of hair. I wonder whether they talk or sing." (Griffiths)

They had low, receding foreheads, huge, beaklike noses, and undershot jaws; their eyes were small and close set, their ears flat and slightly pointed. Feathers grew upon their heads instead of hair. (Burroughs)

"Some of them stroked her smooth, shining sides with their little hands, which Zaidie now found had only three fingers and a thumb. Many ages before they might have been bird's claws, but now they were soft and pink and plump, utterly strange to work as manual work is understood upon Earth." (Griffith)

". . . their arms were very long, ending in long-fingered, heavy-nailed hands. The lower part of the torso was small, the hips narrow, the legs very short and stocky, ending in three-toed feet equipped with long, curved talons." (Burroughs)

"Just listen," she went on, stopping in the opening of the doorway, "have you ever heard music like that on earth? I haven't. I suppose it's the way they talk. I'd give a good deal to be able to understand them. But still, it's very lovely, isn't it?" Zaidie sang the old plantation song... (Griffith)

"Their voices were soft and mellow, and their songs were vaguely reminiscent of Negro spirituals," (Burroughs)

Griffith's Angels of Venus, interestingly, are distinguished only by sizes, which our travellers take for sexual differentiation. But it is not at all clear that they are male and female. Burroughs' Wieroo of Caprona are exclusively male.

Griffith's Angels of Venus are innocents from a Garden of Eden. Meanwhile, Burroughs Angans are simply shallow and superficial, lacking deep emotions or convictions.

What we've got here are two radically different takes on what is essentially the same creatures: Biblical angels transposed to science fiction. Burroughs makes no secret of it, the name 'Angan' is obviously a play on 'Angel'. The Wieroo of Caprona consider themselves the servants of God, and in fact, speaker to God is their highest title. Angels are next to God and above man in the celestial order, the Wieroo consider themselves and in the logic of Caprona, are the most highly evolved 'humans.' Angels are the spirits of the dead gifted with wings, and the Wieroo look like flying corpses. No question is that it's angels all around!

The big difference is that Griffiths goes for a sweet, treacly sentimental take on these creatures, as opposed to their 'mass murder' approach to the Martians. He's completely uncritical, the 'Angels' are by definition good and innocent, and he looks no further.

Burroughs takes on Angels are more mature and completely unsentimental. His Wieroo are an unappealing pinnacle of evolution, having ascended to actual angels, they have left humanity behind. They're literally flying corpses in Burroughs' descriptions, and that's singularly unattractive. The Wieroo are so 'perfected' that they've lost all feminine qualities and therefore are all male. Their perfection leaves them so individualist that they can barely manage a functioning society.

Meanwhile, Burroughs' Angans are an assault on Angels from the other direction. Rather than being divine and innocent, the Angans are merely stupid and shallow. Their innocence, an innocence which Griffiths celebrates, Burroughs denounces as ignorance. The Angans 'innocence' means that they have no convictions, they have no love, no loyalty, they blow in the wind and stand for nothing, they're completely unreliable. They lack the intellectual foundations for anything meaningful.

It's interesting that Burroughs has taken an idea that Griffith used here (and that others used elsewhere) and pushed it so hard and in such a stern direction. There's no sentimentality at all in Burroughs, his characters deal with the Angans and Wieroo face to face. In contrast, Griffiths characters do not 'deal' at all with their Angels, they 'ideal' them. Burroughs has taken practically the same idea and same creature and put a hard spin on it, in such a way that the Angans and Wieroos are comments on our own society and illusions.

In the same way, H.G. Wells took the same notion of evolution of sterile intelligence for Martians that Griffiths worked with, and he too pushed it hard and in stern directions. Griffith's Martians are simply assholes, cold enough to justify Zaidie and Lenox's mass murders. Wells' Martians are actual monsters. But like Burroughs and his angels, Wells uses his Martians to comment on our own society, on our own conceptions. Burroughs Angels and Wells Martians are, in some sense, reflections of our own society, and of our own hypocrisy. On the other hand, Griffith's Martians and Angels are simply others, they are not reflections at all, and there is no sense of hypocrisy or irony in dealings with them.

I suppose that this is why we remember and continue to read Burroughs and Wells, whereas Griffiths has fallen completely out of sight. I am not, by the way, suggesting that Griffith inspired any part of Burroughs. Griffith simply drew superficially from the common well of ideas and inspirations floating around at the time. Burroughs drew more and drank deeper of that well, and there you have their differences and commons.

Despite the similarities of Angels and Angans on Venus, even that comes from the common well. If Mars was a planet of war, Venus was the planet of love. You expected monsters on Mars and Angels on Venus. At best, Wells may have read Griffith and took his Angels of Venus as a sloppy, sentimental slap in the face. If so, then the Angans and Wieroo are a couple of stiff haymakers in rejoinder.

Be that as it may, it seems that the creatures that Zaidie and Lenox meet on Venus differ from Burroughs' Angans only in the point of view of the observers. They're Angans, they're on Amtor, its as simple as that.

ACOLUMBUS OF SPACE, 1909, GARRETT PUTNAM SERVISS

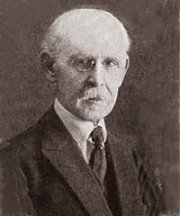

Garrett Putnam Serviss was an interesting American newspaperman science fiction writer who lived between 1859 and 1929.

Garrett Putnam Serviss

Among his notable works of science fiction were Edison�s Conquest of Mars, an unofficial and rather badly done sequel to H.G. Wells War of the Worlds. He hadn�t actually read War of the Worlds, merely gotten some descriptions, it seems. The plot loosely is that Thomas Edison is so offended by the Martians attempted invasion of England that he invents spaceships and ray guns and takes a fleet to put paid to the Martians. Along the way, he rescues a beautiful Princess from the asteroid Ceres, fights Martians who are not tentacled creatures but humanoid asswipes, and eventually destroys the enemy by melting the polar caps and flooding Mars. It�s available on the net, if you care to read it, though perhaps the less said the better.

Other works include the Great Deluge, wherein Earth is almost drowned passing through a watery nebula, the _Moon Metal_about a mad scientist, the Moon Maiden and A Columbus of Space. He also wrote a book about astronomy called Curiosities of the Sky which is also available on the net and which goes a ways towards showing the thinking of the time as to what the universe was like.

Serviss shows a lot of what was good and bad about the science fiction writers of his day. On the one hand, the guy did his homework, and his fiction does represent some of the state of the art thinking of the day. It was true science fiction, in terms of being fairly grounded in the science as it was understood then. The fact that its nonsense now doesn�t change that.

On the other hand, and we see the same strengths and weaknesses with Griffiths as well, Serviss never bothers to push the envelope. H.G. Wells used his science fiction as a philosophical commentary on the world around him, and even Burroughs was constantly tilting at social windmills, sometimes overtly, sometimes covertly. But these guys, Serviss and Griffiths, were mostly content to reflect the illusions and self absorptions of the society they lived in. This was comfortable science fiction, since it simply reaffirmed the prejudices of the reader. Nowadays, this makes it seem horribly trite and dated, it ages in a way that Burroughs and Wells don�t. And more than that, because this novel carries the blind spots of the age, you have to sit back and marvel at what utter bastards the protagonists are.

A Columbus of Space, written in 1909, only a few years before Burroughs wrote_A Princess of Mars_ is Serviss� Venus epic, and it is close enough to the works of Kline, Burroughs and Farley that it is worth a look. The novel begins with the very odd pretension that the adventure is chronicled by the best friend of the hero, Edmund Stonewall.

A Columbus of Space, written in 1909, only a few years before Burroughs wrote_A Princess of Mars_ is Serviss� Venus epic, and it is close enough to the works of Kline, Burroughs and Farley that it is worth a look. The novel begins with the very odd pretension that the adventure is chronicled by the best friend of the hero, Edmund Stonewall.

Edmund Stonewall, we discover is not only an American blueblood, but he�s an athlete, scholar, multi-millionaire and inventor. In short, he�s pretty larger than life, which may explain why Serviss is reluctant to get into his head. On the other hand, when we see him in action, he is hardly superhuman, merely a little smarter than the average bear.

Anyway, be that as it may, Edmund invents himself an atomic powered spaceship, and he goes off on a trip to Venus with a couple of friends. Back then, science heros were inventing all manner of spacecraft, magnetic powered, psychic powered, ether powered, so the fact that its atom powered is not necessarily prophetic, its just a mcguffin.

Edmund gets to Venus, which he discovers is tidally locked. One side of Venus is always facing towards the sun. Edmund first lands on the glacier covered dark side and discovers a flight of steps leading down into underground tunnels. He also discovers the inhabitants of these tunnels:

�Standing on the steps, just below the level of the ground, and intently watching us, with eyes as big and luminous as moons, was a creature shaped like a man, but more savage than a gorilla! For two or three minutes the creature continued to stare at us, motionless; and we stared at him. It was so dramatic that it makes my nerves tingle now when I think of it. His eyes alone were enough to harrow up your soul. Huge beyond belief, round and luminous as full moons, they were filled with the phosphorescent greenish-yellow glare that sometimes appears in the expanded pupils of a cat or a wild beast. The great hairy head was black, but the stocky body was as white as a polar bear. The arms were apelike and very long and muscular, and the entire aspect of the creature betokened immense strength and activity.�

Okay, the eyes are big, and the black head white body colour scheme is odd, but this creature, an Ape-man, could easily pass for one of Burroughs' Nobargans, Kline's Ibbits or Farley�s Roi. Ape men were to be expected on Venus. Edmund promptly shoots him dead.

After that, the descend into the caves and meet the rest of the tribe of ape men, who are a pretty peaceful and timid bunch, unless their tribal rituals are upset. Edmund and his friends hang out there for a while, eventually shooting a bunch more of the ape men. These ape men, in addition to inhabiting hand carved tunnels, communicating with a degree of telepathy and possessing iron are actually fairly civilized, not that Edmund and his friends admit it.

Nobody stops to wonder what the hell they�re eating on what is believed to be the permanently frozen, glacial dark side.

Eventually, Edmund gets bored, so they decide to travel to the light side. Although the Ape-men have no clue as to whats over there, Edmund decides to rig up a sled to take them all with him. Along the way, they fight through a brutally stormy area between light and dark side, and all but one of the tribe is killed. Congratulations Edmund.

To be fair to Edmund and his friends, they do tend to feel bad when they shoot or kill natives. But they just keep killing them!

Anyway, on the bright side, they find an ocean and jungle islands. They encounter a flying airship, apparently some sort of dirigible or primitive mechanical craft, and make the acquaintance of the crew. The light side Venusians turn out to be very human looking and very blonde.

�At first, as I have said, the resemblance of their crews to inhabitants of the earth seemed complete. One would have said that we had met a yachting party, composed of tall, well-formed, light-complexioned, yellow-haired Englishmen, the pick of their race. At a distance their dress alone appeared strange, though it, too, might easily be imitated on the earth. As well as I can describe it, it bore some resemblance, in general effect, to the draperies of a Greek statue, and it was specially remarkable for the harmonious blending of soft hues in its texture.�

The captain of the ship is a beautiful blonde princess. Unfortunately, they can�t speak the language, but Edmund picks up enough telepathy to get by.

Wow, an alien Princess. Who would have thought?

Led by the Princess, they visit the city of the Venusian people. It is literally a floating city, suspended by balloons. The descriptions of the city are probably some of the most beautiful passages in the book. The Venusians described are quite civilized. They�re so civilized, in fact, that while they have airships, they do not have weapons of any sort. They don�t know what the pistols are.

One of Edmund�s pals, Jack, the homicidal one, accidentally shoots the Princess, but she forgives them. Later, Edmund and friends get in trouble with the evil snivelling Prince who wants the Princess for himself (and didn�t you see that coming).

The result at one point is an aerial chase, and at another point, the evil prince manages to get them kidnapped and dropped off on a savage jungle island full of monsters. The Venusians, not having weapons, are obviously restricted to their one island nation. They just don�t have the hardware necessary to beat off monsters which include a giant tarantula and a tentacled whatsit.

Eventually, everything is sorted out though, and Edmund and his friends hang about the city, where his friend Jack gets them into more trouble, this time by messing with holy artifacts or somesuch.

But then, at the end, the clouds part, the sun shines down and because the sun is so much stronger on Venus, everyone gets sunstroke induced psychosis and goes around killing each other and burning their city down. It�s a touch vaguely reminiscent of Isaac Asimov�s later story �Nightfall.�

Edmund loses his princess, and they all return to Earth a little sadder and wiser, having thinned out the population of Venus appreciably.

So what�s the bottom line? It�s a fairly serviceable read, the writing lacks the pace and excitement of Burroughs or his imitators. Edmund for much of his time on Venus, seems to be looking for something to do, his and his friends adventures have a contrived feel. There�s no �big story� which animates the novel. Indeed, a lot of the miseries that Edmund and his friends experience are self inflicted, and they�re such unctious, oblivious, condescending tourists that you lose a lot of sympathy for them.

On the other hand, individual chapters can be quite good, and some of the descriptions are remarkably vivid. Reading through the eyes of a Burroughs fan, you can just see Serviss trying for and just barely missing his mark again and again.

As for Serviss� concept of Venus? You could slot it right into Otis Adelbert Kline�s Zarovia and no one would notice. Or for that matter, you could tuck it away in a corner of Burroughs Amtor or Farleys Poros and it would fit quite well. It is, functionionaly identical to the later Venus� of these three writers.

Indeed the parts that don�t quite fit don�t really make sense. If the planet always keeps one face to the sun at all times, and the dark side is permanently dark and cold, how are the ape-men surviving? It makes more sense to suggest that Edmund has gotten this wrong and that the planet is rotating more quickly.

The better explanation is that they�ve landed in a polar region during the winter, and the endless night is merely the axial tilt. The creatures they encounter are actic Nobargans, who are riding out the winter in their tunnels.

When they travel, they move south out of the polar region and down latitudes where a real day/night cycle is taking place. The stormy area which they believe forms the dividing line between dayside and nightside is merely a geologically unstable area of boiling ocean or storm, as we might have seen around Farley�s Island of Cupia.

As for the blond sky riders of Venus, they�re simply a lost offshoot of the Zarovia culture, one which being safe on their island nation, have abandoned weapons and learned to develop primitive aircraft. They�re no threat to Olba.

Hell, without too much effort, we could find an Island or region for them, off the beaten path, but still on Venus.

Anyway, Serviss is worth checking out, if only for the historical value, and his Venus cements in solidly with those of later writers. This illustrates just how universal that vision of Venus was. It wasn�t just the creation of Burroughs, or Kline or even Farley, but like the Mars of the Pulps, it was a shared common landscape as detailed and as real as the wild west.