Todd Marinovich: The Man Who Never Was (original) (raw)

Originally published in the May 2009 issue of Esquire. To read every Esquire story ever published, upgrade to All Access.

The Fallbrook Midget Chiefs are fanned out across the field on a sunny autumn day in southern California, two dozen eighth graders in red helmets and bulbous pads. Whistles trill and coaches bark, mothers camp in folding chairs in the welcoming shade of the school building, younger siblings romp. Fathers hover on the periphery, wincing with every missed tackle and dropped pass.

Into this tableau ambles a tall man with faded-orange hair cropped close around a crowning bald spot, giving him the aspect of a tonsured monk. His face is all angles, his fair skin is sunburned and heavily freckled, his lips are deeply lined, the back of his neck is weathered like an old farmer's. He is six foot five, 212 pounds, the same as when he reported for duty twenty-one years ago as a redshirt freshman quarterback at the University of Southern California, the Touchdown Club's 1987 national high school player of the year. The press dubbed him Robo Quarterback; he was the total package. His Orange County high school record for all-time passing yardage, 9,182, stood for more than two decades.

Now he is thirty-nine, wearing surfer shorts and rubber flip-flops. He moves toward the field in the manner of an athlete, loose limbed and physically confident, seemingly unconcerned, revealing nothing of the long and tortured trail he's left behind.

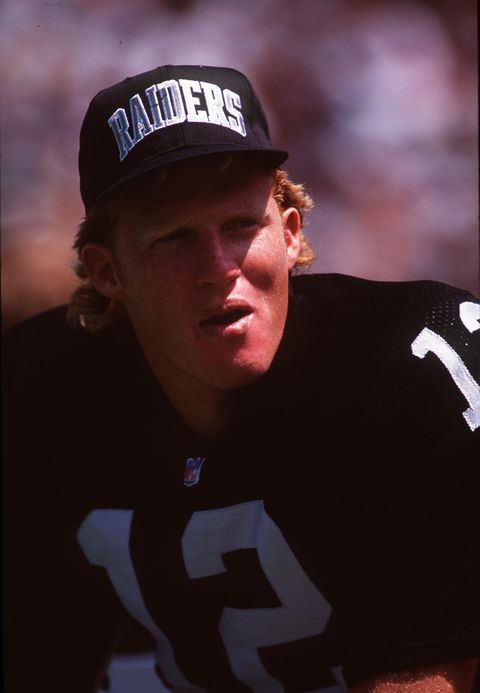

A coach hustles out to meet the party. He is wearing an Oakland Raiders cap. "Todd Marinovich!" he declares. "Would you mind signing these?" He produces a stack of bubble-gum cards. As Todd signs, everybody gathers and cops a squat. Somebody tosses him a football, like a speaking stick.

"Hi, my name is Todd. I played waaaay before you guys were even born." Without his sunglasses, resting now atop his head, his blue eyes look pale and unsure. Raised much of his life on the picturesque Balboa Peninsula, he speaks in the loopy dialect of a surfer dude. He once told a reporter in jest that he enjoyed surfing naked at a spot near a nuclear power plant. Thereafter, among his other transgressions — nine arrests, five felonies, a year in jail — he would be known derisively for naked surfing. "One thing that I am today and that's completely honest," he tells the Chiefs. "I wouldn't change anything for the world."

Paul Harris//Getty Images

Marinovich standing on his high school field.

As he speaks, Todd fondles and flips and spins the ball. It seems small in his hands and very well behaved, like it belongs there. When he was born, his father placed a big plush football in his crib. Marv Marinovich was the cocaptain of John McKay's undefeated USC team of 1962. He played on the line both ways. The team won the national championship; Marv was ejected from the Rose Bowl for fighting. After a short NFL career, Marv began studying Eastern Bloc training methods. The Raiders' colorful owner, Al Davis, made him one of the NFL's first strength-and-conditioning coaches. Before Todd could walk, Marv had him on a balance beam. He would stretch the boy's little hamstrings in his crib. Years later, an ESPN columnist would name Marv number two on a list of "worst sports fathers." (After Jim Pierce, father of tennis player Mary, famous for verbally abusing opponents during matches.)

At the moment, Marv is sitting at the back of the Chiefs gathering, resting his bum knee, eating an organic apple. Nearly seventy, he has bull shoulders and a nimbus of curly gray hair. His own pale-blue eyes are focused intently on his son's performance, as they have been from day one.

"I was the first freshman in Orange County to ever start a varsity game at quarterback," Todd continues. "I broke a lot of records. Then I chose to go to USC. We beat UCLA. We won a Rose Bowl. It's quite an experience playing in front of a hundred thousand people. It's a real rush. Everyone is holding their breath, wondering, What's he gonna do next? After my third year of college, I turned pro. Here's a name you'll recognize: I was drafted ahead of Brett Favre in the 1991 draft. I played for three years for the Raiders. I made some amazing friends — we're still in touch."

Todd surveys the young faces before him. In about a minute, he has summarized the entire first half of his life. He looks down at the football. "Any questions?"

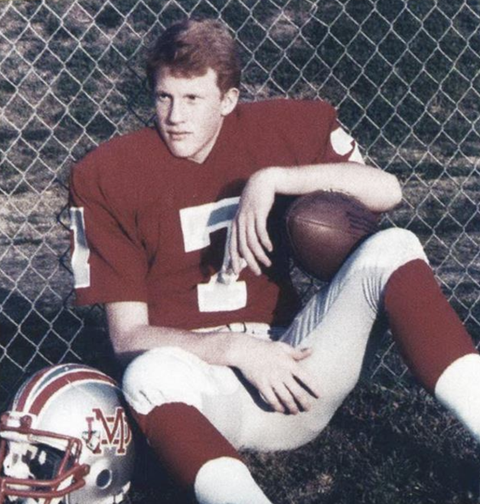

Stephen Wade//Getty Images

Marinovich at the Rose Bowl, 1990.

One kid asks Todd if he fumbled a lot. Another wants to know how far Todd can throw. The coach in the Raiders cap — they call him Raider Bill — asks Todd how he got along with his coaches, eliciting a huge guffaw from both Todd and Marv, which makes everybody else crack up, too.

Then Todd points the football at a boy with freckles.

"You said you only played three years in the NFL," the boy says, more a statement than a question.

"Correctamundo," Todd replies, at ease now, playing to the crowd, not really thinking about what's coming next — which has always been his biggest strength and maybe also his biggest weakness.

"What ended your career?" the boy asks.

"What ended my career..." Todd repeats. His smile fades as he searches for the right words.

The Newport Beach Cheyennes were scrimmaging the best fourth-grade Pop Warner team in Orange County. It was September 1978. Todd was nine years old, playing his first year of organized tackle football.

Todd was the quarterback, a twig figure with flaming-orange hair. The opposing team was anchored by its middle linebacker, one of those elementary-school Goliaths, physically mature for his age. With time waning and the score close, the game on the line, the Cheyennes' coach opted to give his second-string offense a chance. In this scheme, Todd moved to fullback. Over in his spot near the end zone, Marv's eyes bugged. Why isn't this idiot going for the win?

The Marinovich family had recently returned from living in Hawaii, where Marv, after coaching with the Raiders and the St. Louis Cardinals, had done a stint with the World Football League's Hawaiians. As Marv sorted out his work status, his family of four was living with the maternal grandparents in a little clapboard house on the Balboa Peninsula. Once a summer beach shack, it had been converted over the years into two stories, four bedrooms. The Pacific Ocean was two long blocks from the front deck; Newport Harbor was two short blocks from the back door, its docks crowded with yachts and pontoon party boats. In summer came the throngs: a nonstop party.

Ken Levine//Getty Images

Playing for the Raiders, 1992.

Todd's mom is the former Trudi Fertig. In high school, she held several swimming records in the butterfly. A prototype of the late-fifties California girl, Trudi was a Delta Gamma sorority sister at USC; she quit college after her sophomore year to marry the captain of the football team. Trudi's father, C. Henry Fertig, was the police chief of nearby Huntington Park. German-Irish, the son of a blacksmith, he was the one who'd passed down the carrot top. The Chief, as he was known to all, was the "most visible of all the Trojan alums," according to The Orange County Register. Before every USC game you'd find him, wearing his cardinal-colored shirt and bright gold pants, tailgating in his regular spot in front of the L. A. Coliseum, where the Trojans play their games. (After the Chief's death in 1997, at the age of eighty, the alumni laid a brass plaque on the hallowed spot.)

The Chief's son was Craig Fertig, a former USC quarterback, responsible for one of the greatest Trojan victories of all time, a comeback against undefeated Notre Dame in 1964. He was associated with the program for nearly fifty years as a coach, assistant athletic director, TV commentator, and fan until his death, the result of organ failure due to alcoholism.

Marv Marinovich grew up with his extended family on a three-thousand-acre ranch in Watsonville, in northern California. The spread was owned by his Croatian grandfather, J. G. Marinovich. According to family lore, J. G. was a general in the Russian army, a cruel man who'd overseen the battlefield amputation of his own arm. After high school, Marv played football for Santa Monica City College. The team went undefeated and won the 1958 national junior-college championship. From there Marv transferred to USC. He was known for foaming at the mouth. After the championship, he was named Most Inspirational Player. He still has the trophy.

Drafted by the L. A. Rams of the NFL and by the Oakland Raiders of the AFL, Marv "ran, lifted, pushed the envelope to the _n_th degree" in order to prepare for the pros. One exercise, he says: eleven-hundred-pound squats, with the bar full of forty-five-pound plates, with hundred-pound dumbbells chained and hanging on the ends because he couldn't get any more plates to fit. "And then I would rep out," he recalls. "I hadn't yet figured out that speed and flexibility were more important than weight and bulk. I overtrained so intensely that I never recovered."

After a disappointing three-year career with the Raiders and Rams, Marv turned to sports training. Over time, he would develop his own system for evaluating athletes and maximizing their potential. Much of the core- and swimming-pool-based conditioning programs in use today owe nods to Marv's ideas. His latest reclamation project: Pittsburgh Steelers safety Troy Polamalu. (See Polamalu and Marv on YouTube.)

"What ended my career..." Todd repeats. His smile fades as he searches for the right words.

With the birth of his own two children, Traci and Todd, came the perfect opportunity for Marv to put his ideas into practice. "Some guys think the most important thing in life is their jobs, the stock market, whatever," he says. "To me, it was my kids. The question I asked myself was, How well could a kid develop if you provided him with the perfect environment?"

For the nine months prior to Todd's birth on July 4, 1969, Trudi used no salt, sugar, alcohol, or tobacco. As a baby, Todd was fed only fresh vegetables, fruits, and raw milk; when he was teething, he was given frozen kidneys to gnaw. As a child, he was allowed no junk food; Trudi sent Todd off to birthday parties with carrot sticks and carob muffins. By age three, Marv had the boy throwing with both hands, kicking with both feet, doing sit-ups and pull-ups, and lifting light hand weights. On his fourth birthday, Todd ran four miles along the ocean's edge in thirty-two minutes, an eight-minute-mile pace. Marv was with him every step of the way.

Now, late in one of Todd's first games in Pop Warner, the coach sent a play into the huddle, a handoff to the halfback. As fullback, Todd's job was to be lead blocker.

The ball was snapped. Todd led the halfback through the hole.

He'd just cleared the line of scrimmage when Goliath-boy stepped into the gap and delivered a forearm shiver very much like the one that had gotten Marv ejected from the Rose Bowl. Todd crumpled to the ground. Blood flowed copiously from his nose.

The whistle blew. As Todd was being cleaned up, Marv convinced the coach that Todd needed to go back in the game. Immediately. At quarterback.

Esquire

The original layout for this story in Esquire magazine.

Todd stood over center, his nose still bleeding. Part of him felt like crying. The other part knew that it was the last few seconds of the scrimmage and the team was down by only a few points. For as long as he could remember, no matter what sport he played, he always had to win.

He took the snap and faded back, threw a perfect pass into the back corner of the end zone. "That has always been my favorite route," he says now, sitting outside a little coffee shop on Balboa Boulevard, drinking a large drip with six sugars and smoking a Marlboro Red. He tells the story from a place of remove, as if describing something intimate that happened to someone else. "I remember seeing the ball. It was spiraling and there was blood just flying off of it, splattering out into the air."

When the catch was made, there was silence for a beat. "And then I remember the parents cheering."

Six years later, on the opening night of the 1984 football season, Todd once again gathered himself as best he could, rising to one knee on the turf at Orange Coast College. There were seven thousand fans in the stadium. He'd just been blasted by two big studs from the celebrated front line of the Fountain Valley High School Barons.

Three days before he'd even set foot in a ninth-grade classroom, the six-three, 170-pound freshman was the starting quarterback for the varsity team at Mater Dei High School in Santa Ana, the largest Catholic high school west of Michigan. In a sports-mad county known for its quarterbacks — from John Huarte and Matt Leinart to Carson Palmer and Mark Sanchez — Todd's freshman start was a first.

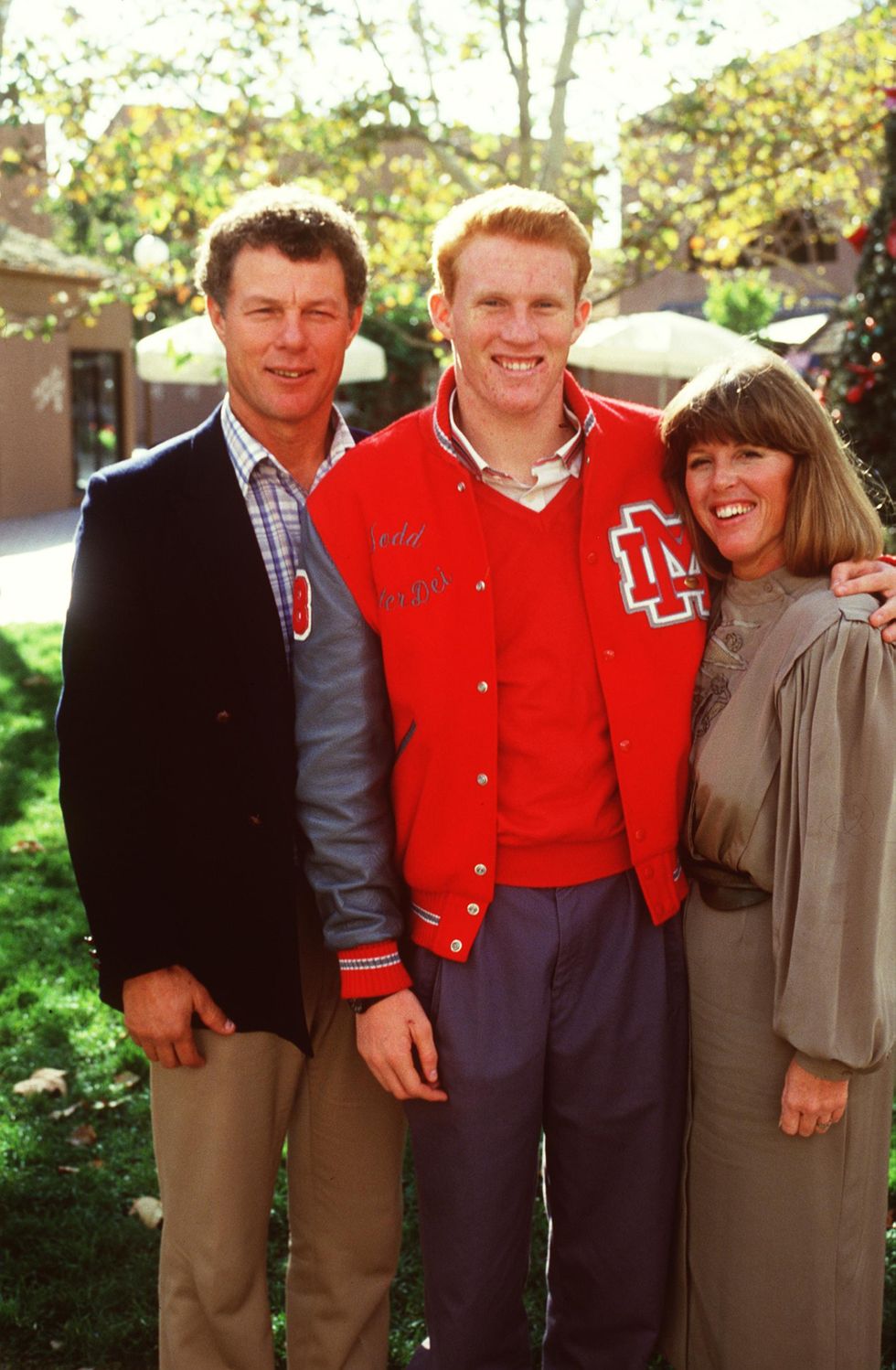

Paul Harris//Getty Images

Marinovich and his parents, 1986.

Todd fought for breath. His head was ringing, his vision was blurred, he wanted to puke. Later he would recognize the symptoms of his first concussion. Marv's conditioning was designed to train the body and the mind to push beyond pain and fear. Throughout his career, Todd would be known for his extraordinary focus and will — qualities that would both enable and doom him. Two years from now, the left-hander would lead a fourth-quarter rally with a broken thumb on his throwing hand. Five years from now, he would throw four college touchdowns with a fractured left wrist. Sixteen years from now, he'd throw ten touchdowns in one game, tying an Arena Football League record, while suffering from acute heroin withdrawal.

Acting on instinct, fifteen-year-old Todd rose to his feet and peered out of the echoing cavern of his helmet. He searched the sideline, looking for the signal caller, his next play. A teammate grabbed him by the shoulder pads, spun him around to face the Mater Dei bench. "We're over here, dude," he told Todd.

Back in seventh grade, Todd had set his goal: to start on a varsity team as a ninth grader. Marv made a progress chart and put it up in the garage; they worked every day. "It was brutal," Todd recalls. "Sometimes I didn't want anything to do with it. He'd give me the look, like, 'Well, fine, but you're gonna get your ass kicked when you start to play.' " Along the way, Marv consulted a series of experts: Tom House, the Texas Rangers' innovative pitching coach, found Todd's throwing motion to be 4.53 inches too low. A vision specialist in Westwood made Todd wear prism glasses, stand on a balance beam in a dark room, and bounce a ball while reciting multiplication tables.

By the summer before ninth grade, Todd was penciled in as Mater Dei's fifth-string quarterback. His typical week, as reported by the Register: Four days of weight lifting, three days of light work and running. Daily sessions with Mater Dei's assistant basketball coach. Twice weekly with a shooting coach. Two hours daily throwing the football. Twice weekly with a quarterback coach. Thrice-weekly sprint workouts with a track coach. There were also Mater Dei basketball club games and twice-daily football workouts.

"I don't think any of the kids were ever jealous of Todd, because they knew that when they left that field or court or gym, Todd was still going to be there for many, many hours," Trudi recalls. When Todd and Traci were growing up, Trudi worked as a waitress during the periods when Marv wasn't employed. Sometimes she secretly took Todd to McDonald's. The Chief fed him pizza and beer. Though Traci once wrote of hearing Todd cry in his room, nobody wanted to butt heads with Marv. Like an obsessed scientist, he had tunnel vision. "He didn't do reality too well," Trudi says.

Todd fought for breath. His head was ringing, his vision was blurred, he wanted to puke.

Todd lost that first game against Fountain Valley, 17-13, but he showed promise. Shut down completely after that blow in the first quarter, he gained composure as the evening progressed, completing nine of seventeen passes for 123 yards and two interceptions, the second of which foiled a fourth-quarter drive that could have won the game. The Register would report: "If not for Marinovich... the Monarchs wouldn't have had an offense to speak of."

After the final gun, Todd stood with his parents. His new teammates drifted over and surrounded him. "When I was growing up, the term my mom used was 'terrifyingly shy,' " Todd says. "That's why I always loved being on a team. It was the only way I could make friends. It was really amazing to have these guys, these upperclassmen, come over. And they're like, 'Hey, Todd, let's go! Come out with us after the game. It's party time!' "

Todd looked at Marv. The old man didn't hesitate. "He just gave me the nod, you know, like, 'Go ahead, you earned it.'

"We went directly to a kegger and started pounding down beers," Todd recalls.

It was January 1988, opening night of basketball season. With fifty-eight seconds left, the score was 61-all. Todd flashed into the key, took a pass from the wing. He made the layup and drew the foul. Whistle. Three thousand fans in the arena at the University of California, Irvine, went nuts. The six-five, 215-pound high school senior pumped his fist in celebration.

During his two years at Mater Dei, Todd had thrown for nearly forty-four hundred yards and thirty-four touchdowns. But the Monarchs' record was mediocre; they had no blocking to protect Todd. So Marv had engineered his son's transfer to Capistrano Valley High, a public school in Mission Viejo. The team's head football coach, Dick Enright, was a USC alum and longtime friend of Marv's. As head coach at the University of Oregon, Enright had groomed quarterback Dan Fouts. Under Enright, Todd would go on to break the all-time Orange County passing record. He was named a Parade magazine All-American and the National High School Coaches Association's offensive player of the year.

Esquire

The May 2009 Esquire cover, the issue in which this story originally ran.

Then the January 1988 issue of California magazine hit the stands with Todd's picture on the cover. The headline: ROBO QB: THE MAKING OF A PERFECT ATHLETE. A media onslaught ensued. They called Todd the bionic quarterback, a test-tube athlete, the boy in the bubble. All over the world, people were talking about Todd's amazing story. In truth, he was leading a double life.

"I really looked forward to giving it all I had at the game on Friday night and then continuing through the weekend with the partying. It opened up a new social scene for me — liquid courage. I wasn't scared of people anymore," Todd says.

At Mater Dei, Todd had also begun smoking marijuana. By the time his junior year rolled around, he says, "I was a full-on loady." His parents had divorced just before his transfer, and he was sharing a one-bedroom apartment with Marv near Capistrano. "Probably the best part of my childhood was me and Marv's relationship my junior and senior years," Todd says. "After the divorce, he really loosened up. It was a bachelor pad. We were both dating."

Every day before school, Todd would meet a group at a friend's house and do bong hits. They called it Zero Period. Some of the guys were basketball players, others were into surfing, skateboarding, and music — the holy trinity of the OC slacker lifestyle.

"Pot just really relaxed me. I could just function better in public," he says. "I never played high or practiced high. It wasn't as hard on my body as drinking. I thought, Man, I have found the secret. I was in love."

Now it was January of his senior year, the opening game of basketball season. Todd was a swingman, the high scorer. The Capo Cougars were one of the top-ranked teams in the county_._ The contest against archrival El Toro High School had come down to the wire. Todd had just broken the tie with a layup. Then he hit the foul shot: 64-61.

El Toro inbounded the ball; Capo stole it. Pass to Todd. Hard foul in the paint. Todd went to the line again, two shots. Thirty-seven seconds left to play.

The crowd was screaming, pounding the floor. Behind the basket, dozens of El Toro students were wearing orange wigs to mock the carrot-topped Robo Quarterback. As Todd went through his foul-shot ritual, something broke his focus. The opposing fans were chanting: "Marijuana-vich! Marijuana-vich! Marijuana-vich!"

"I was supposed to be shooting free throws, but I was really glancing into the stands. I was trying to see if my father noticed," Todd told the Los Angeles Times later.

He put it out of mind and nailed both shots. Game over.

No matter what the teams' record or national ranking, UCLA versus USC is always the biggest game of the year. The sixtieth meeting occurred in November 1990. From the opening kickoff, the advantage seesawed. With less than a minute to go, the score was 42-38 in favor of UCLA. Todd and his Trojan squad began operating on their own twenty-three. A field goal wouldn't do.

On third down, Todd completed a twenty-seven-yard pass to his favorite target, five-foot-nine Gary Wellman, a future Houston Oiler. On the next play he hit Wellman again for twenty-two yards.

With sixteen seconds left, the football was spotted on the UCLA twenty-three-yard line. USC coach Larry Smith called for a time-out. Todd and his corps of receivers jogged to the sideline. A hush fell over the Rose Bowl crowd of 98,088.

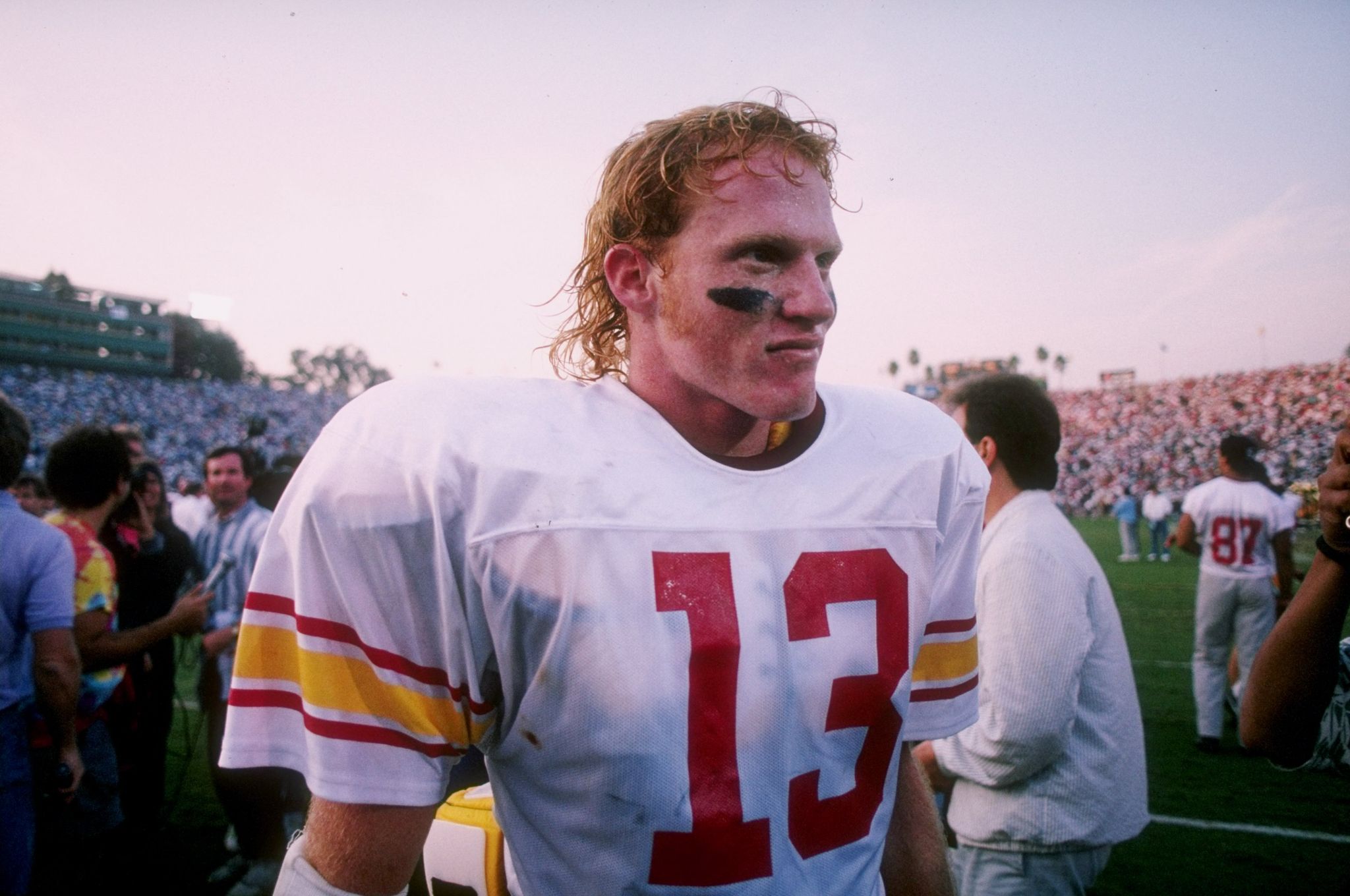

Getty Images//Getty Images

Marinovich, wearing the #13 jersey, in a 1991 game.

Although he was recruited by every notable college, no other school really had a chance over USC. Todd's sister was a senior and his first cousin was planning on attending. His uncle Craig Fertig was an assistant athletic director. When Todd had visited USC that year, he'd been taken down onto the field of the empty Coliseum — where he'd watched games with the Chief his entire life — and they put his name up on the scoreboard, complete with piped-in crowd noise. After that, Todd was taken by his All-American escort to a party on campus. "There was a three-and-a-half-foot purple bong. I was like, 'I'm home.' I even had my own weed on me," Todd recalls.

Todd redshirted his first year at USC. His second year he started every game, completing 62 percent of his passes for twenty-six hundred yards and sixteen touchdowns, leading the 1989 Trojans to a 9-2-1 record, a Pac-10 title, and a Rose Bowl victory over Michigan. Todd was named freshman player of the year. There was Heisman talk, speculation he'd leave early for the NFL.

At the opening of the next season, however, Coach Smith told reporters he wasn't yet decided on his starting quarterback. Smith was a flinty Ohio native who stressed discipline. Of all the coaches he'd ever had, Todd says, he hated Smith the most. Smith seemed determined to break the kid, going so far as to outlaw flip-flops on road trips. Smith told Marv privately he suspected Todd was using drugs. During the two months leading up to the UCLA game, Todd had been repeatedly drug tested but never failed. He'd been suspended from the team for missing classes. He'd been benched as a starter for one set of downs. (When he returned to the game, the crowd booed; he threw a seventy-seven-yard touchdown pass.)

Now Todd and his receivers reached the sideline. "What do you want to do?" Coach Smith asked his quarterback.

Todd's face flushed to hot pink. "You're asking me what I want to do? Why start now?"

Todd turned to his receivers standing behind him. They believed in him. They'd seen his magic. His last-minute comeback against Washington State the previous season is still remembered as "the Drive": A textbook ninety-one-yard march downfield — with eleven crucial completions, including a touchdown pass and a two-point conversion — it prompted a call from former President Ronald Reagan.

Todd's face flushed to hot pink. "You're asking me what I want to do? Why start now?"

Todd turned back to his coach. "This is what we're gonna do," he told Smith, yelling over the crowd. "You're gonna stay the fuck over here while we go win this game."

Todd and his boys jogged back to the huddle. Todd called the play. The ball was on the twenty-three; sixteen seconds left. Wellman was in the slot. The pass was designed to go to him. But as Todd took the snap, he saw Wellman get jammed at the line.

"Whenever a receiver doesn't get a clean release," Todd recalls, "you got to go away from him, 'cause it just screws up the timing. So I looked back to the other side, and I saw Johnnie Morton on his corner route. He was supposed to run an eighteen-yard comeback, but we'd changed it at the line of scrimmage. Now he was making his move. When Johnnie went to the post, I saw the safety just drive on it, thinking I was throwing there. That's when I knew I had it."

Morton caught the ball deep in the left corner of the end zone, in front of the seats occupied by the Chief and his wife, Virginia. "It's been my favorite pass since Pop Warner," Todd said. "You really can't stop it."

On the evening of Saturday, January 19, 1991, Todd hit the bars on Balboa with his cousin Marc Fertig, a former USC baseball player, and two Trojan footballers. Coming home at 4:00 A.M., the boys were less than ten yards from the family beach house when two cop cars came screeching through the alley.

"I had a little nug on me," a marijuana bud, Todd says. "And a bindle of coke this guy had given me, this fan. It was half a gram. The cop went right for the drugs. Somebody must have tipped somebody off."

Todd was charged with two misdemeanors and allowed into a program for first-time offenders, but his USC career was finished. He declared himself eligible for the NFL draft and signed with IMG, a big agency. For the first time since freshman summer, Todd went back into training with Marv.

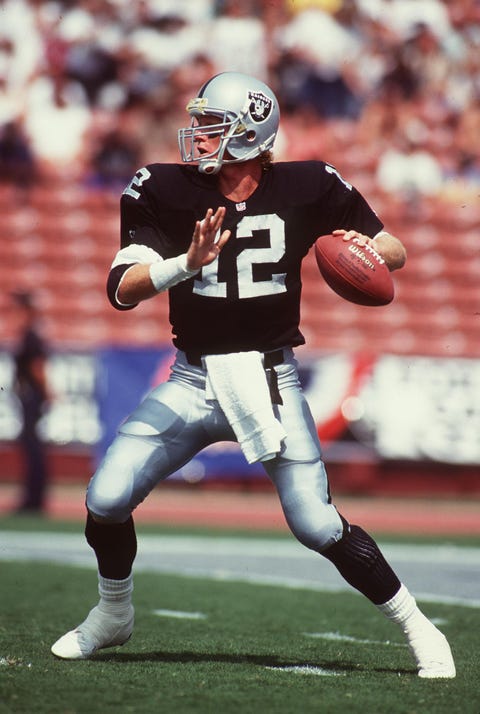

Mike Powell//Getty Images

Marinovich playing for the Los Angeles Raiders against the Cleveland Browns, ’91/’92 season.

Six weeks later, Todd walked onto the field at East Los Angeles College to show NFL scouts what he could do. His long locks had been sacrificed in favor of a bright-orange Johnny Unitas buzz cut, an image makeover suggested by his agent. There were representatives from eighteen teams. Trudi set up a table with lemonade and pastries. Todd was in the best shape of his life. With the help of a former NFL receiver, Todd says, "We put on an aerial show."

The only NFL owner in attendance was Al Davis of the Los Angeles Raiders. Arriving late, Davis climbed up into the stands and sat between his old friends Marv and Trudi. "I kind of knew right then that the Raiders were gonna pick me," Todd says. "I was totally psyched."

At the conclusion of Raider training camp that summer, as tradition dictated, the first draft pick threw a party. Todd had gone twenty-fourth in the first round and signed a three-year, 2.25milliondeal,includinga2.25 million deal, including a 2.25milliondeal,includinga1 million signing bonus. He rented a ranch and hired a company that did barbecue on a huge grill on a flatbed truck. He turned the barn into a stadium with hay-bale seating. He hired strippers, ten white and ten black. The grand finale: three porn stars with double-headed dildos. "They say in the history of the Raiders, it was the best rookie party ever," Todd says.

He made his first professional appearance on no smaller stage than Monday Night Football, an exhibition against Dallas on August 12, 1991. Entering the game with fifteen minutes remaining, he moved the Raiders crisply downfield, completing three of four passes for sixteen yards and a touchdown.

As the season opened, to reduce the pressure on the rookie, coach Art Shell made Todd the third-string quarterback. Seeing little action on the field, he seemed determined to live up to his reputation as an epic partier off it. Arriving at a hotel for an away game, he'd go with the rest of the players to a club. When they returned, he'd go out again. There were women, raves, Ecstasy, coke. Vets would save him a seat at the pregame meal just to hear his stories of the night before. "The cities started running into one another," Todd recalls.

Sometimes, for fun or hangover relief, Todd took pharmaceutical speed before the games. "I wasn't playing, so the warm-ups were my game. They'd have these great stereo systems in the stadiums; they'd be blasting the Stones or whatever. I'd take some black beauties and be throwing the ball seventy-five yards, running around playing receiver, fucking around — and then I was done for the day. I never played. Some guys did play on speed. Or they mixed with Vicodin. They could run through a fuckin' wall and not feel a thing."

The fifteenth week of the season, Todd made his first trip to New Orleans. After a long night of rum drinks in the Quarter, he ended up in bed with two stewardesses; he barely made it back for the pregame meal. The Superdome held seventy thousand screaming fans. "The noise was deafening. My head. I was in hell," Todd remembers now. "I was barely able to make it through warm-ups. I was sweating profusely, trying not to vomit."

Sometimes, for fun or hangover relief, Todd took pharmaceutical speed before the games.

Midway through the game, the Raiders' first-string quarterback, Jay Schroeder, was hit simultaneously from both sides, injuring an ankle. "Coach Shell looks at me, like, Are you ready to go?" Todd recalls. "I shook him off like a pitcher on the mound. I was like, Are you fucking kidding me?"

The following week, with Schroeder still sidelined for the final game of the regular season, Todd made his official debut against the Kansas City Chiefs. Marv was reported to have arrived at the stadium before the gates opened, waiting in line with the other fans to see his boy get his first start. Though the team lost 27-21, Todd completed twenty-three of forty passes for 243 yards. Crowed Los Angeles Times sports columnist Mike Downey: "Sunday was Marinovich's football bar mitzvah. The boy became a man."

The next day was a Monday — five days before the Raiders were due to appear in the AFC wild-card game, also against the Chiefs. Ready to leave home for practice, Todd went to his refrigerator and discovered that he'd run out of clean urine.

As a consequence of his arrest, the NFL had been requiring Todd to take frequent urine tests. Todd felt he couldn't function without marijuana. "It just allowed me to be comfortable in this loud, chaotic world. Especially the world I was living in. I couldn't fathom being sober," he says. To reconcile these conflicting realities, he kept Gatorade bottles of clean urine, donated by non-pot-smoking friends, in the refrigerator at his Manhattan Beach townhouse, one block from the ocean, which he'd purchased for $900,000.

All season long, this had been his pre-test routine: Pour the refrigerated pee into a small sunscreen bottle. Go to practice. Put the bottle in a cup of coffee and leave it in his locker to warm up while attending a team meeting. Come back, stash the bottle inside his compression shorts, beneath his package. Usually he'd ask the supervisor to turn on the water in the sink to aid his shy bladder. "I got it down to a science," he says.

But now he was out of clean pee, another critical responsibility blown off — like the time at USC when he couldn't be bothered to fill out his housing paperwork and ended up a homeless scholarship athlete. Like Marv, the real world wasn't really his thing.

Markus Boesch//Getty Images

Marinovich on the sidelines during the ’91/’92 season.

Luckily, on this Monday morning, one of Todd's former USC teammates was still at his house, left over from the weekend's partying. He didn't do drugs. Unbeknownst to Todd, however, he'd been drinking nonstop since his own game on Saturday.

Soon after, the Raiders got a call from the NFL: Todd's urine sample had registered a blood-alcohol level of .32 — four times the legal limit. "They're like, 'This guy is a fucking full-blown alcoholic,' " Todd says. "They made me check into Centinela Hospital in Inglewood for alcohol detox — and I hadn't even been drinking." The team left without him; he flew later. This time the Chiefs were ready for Todd. He threw four interceptions, fumbled once.

After the season the team held an intervention. Todd spent forty-five days at a rehab facility. The next season, Todd tried to stop smoking pot. Instead, for six weeks, he took LSD after every game — acid didn't show up on the tox screen. After one poor performance, coaches complained that he wasn't grasping the complex offense. Finally, he failed an NFL drug test. Strike two. Back to rehab.

The next August, 1993, near the end of his third training camp, Todd failed a third drug test for marijuana. Al Davis brought the kid into his office. After two seasons, eight games, eight touchdown passes, Todd's NFL playing days were over.

"I was like, Fuck it. I'd been playing my whole life. I'd accomplished my goals. I never said I wanted to play forever. I just wanted to play at the highest level. Even in college, it felt like the shit you had to put up with in order to play wasn't worth it. Those few amazing hours on Sunday were being outweighed by all the bullshit."

Todd packed up his Land Cruiser and drove to Mexico to camp and surf. "I thought I had a ton of money," he says.

It was shortly after Swallows Day in San Juan Capistrano, March 24, 1997. Todd lived in a small house near the beach; a few friends were hanging out. At one point, somebody got the idea to go to the grammar school next door and play dunk hoops on the low baskets.

As the game got going, the motley crew of loadies transformed themselves into ballers. As always, Todd couldn't miss. He was by now twenty-seven. After traveling the world for two years, he'd attempted to return to football, only to blow out his knee on his first day of training camp with the Winnipeg Blue Bombers of the Canadian Football League. During his recovery, an old buddy from Zero Period at Capo had introduced him to the guitar and then later to heroin. Their band, Scurvy, achieved modest success playing at clubs on the Sunset Strip. Then the bassist was busted, ruining hopes for a record deal. For the past three years, Todd had been a full-blown addict.

Going up for a rebound, one guy hurt his back. John Valdez was twenty-nine and weighed about 275 pounds: He went down like a slab of beef. With much difficulty, the guys hauled him back to Todd's bed. In agony, he appealed to his host: "You got anything to help the pain?"

Todd left the room and retrieved his stash of Mexican black-tar heroin. "I fixed myself first," he says. "I remember it being strong stuff, so I just gave him a fraction of the amount." A few minutes later, returning from a cigarette break on the front porch, he checked on Valdez. "He's frothing from the mouth. He's fuckin' blue."

Todd ran outside and retrieved the garden hose — it was easier than lugging Valdez to the shower, as he'd seen in movies. When that didn't help, Todd started slapping him in the face.

He's frothing from the mouth. He's fuckin' blue.

"I'm fucking hitting this guy with everything I've got," he recalls. "And I swear, I could see his spirit struggling to leave his body. I don't tell this story much; people think I was hallucinating. But on heroin you don't hallucinate. You do not fucking hallucinate on fucking heroin. The only way I could describe it is like when you see heat waves on the beach — when the heat waves eddy up and warp your vision. It was like that, and it was colorful. I actually saw it, the life force or whatever, as it would leave the top of his head, and he'd become this fleshbag, and then I would smack the shit out of him and I would see it actually coming back into him."

The friends had scattered; there was one guy left with them in the house. Todd yelled, "Call fuckin' 911!"

As the other guy cleaned up the drugs and the syringe, the dispatcher coached Todd through CPR. Finally the paramedics arrived, along with sheriff's deputies.

The day before, Todd had helped a buddy harvest his marijuana crop. As a thank-you, he'd gotten a trash bag full of cuttings, not bud but still smokable. He'd stashed the bag in his garage rafters with his surfboards and promptly forgotten about it. As the paramedics wheeled out Valdez on a gurney, one of the deputies came into the room holding the trash bag of pot. "Where are the plants?" he demanded.

"I'm not a grower," Todd tried to explain. "See, this buddy of mine — "

Just then, another deputy entered the room. He was carrying two half-dead pot plants that Todd had set up in his laundry room with a drugstore-variety grow light.

Todd was charged with felony marijuana cultivation. He served two months in jail and a third at a minimum-security facility in OC known as the Farm.

In April 1999, just shy of his thirtieth birthday, Todd was finally cleared to play again by the NFL. He promptly herniated a disk playing pickup hoops. That summer, he worked out for several teams. The Chargers and the Bears showed real interest, but he failed the physical; no deals could be made. He ended up signing as a backup quarterback with the B. C. Lions of Vancouver, in the Canadian Football League.

Except for a little pot, Todd was drug free for the first time in years. His roomie was Canadian. About two weeks into his stay, he asked Todd if he wanted to go with him "to check his babies."

It turned out he was growing potent BC bud. On the way home, Todd stopped at a head shop to buy a bong. There were little vials scattered everywhere on the ground. His junkie warning system sounded a shrill alarm.

Esquire

The middle pages of this story in the May 2009 issue of Esquire.

Todd had arrived in his own personal land of Oz, a place were junkies bought and used heroin openly and cops only got involved if somebody OD'd. The heroin was called China White. It was infinitely more potent than the black tar Todd had used before — and relatively cheap. He got into a routine: "The day before every game, we would do a walk-through in the dome — that was my day for needle exchange. All my years of being a dope fiend, the hardest part was always getting needles. I was getting good coke and really pure heroin and combining them. That's all I wanted to do. I woke up, fixed, went to practice. Thank God I was just backing up. I was just the clipboard guy, playing the opposing quarterback in practice."

Once, during halftime at a home game, Todd retrieved a premade rig out of his locker and went to the bathroom to shoot up. Sitting on the toilet, half listening to the chalk talk, he slammed the heroin. As the team was leaving the locker room for the second half, he struggled with the screen in his glass crack pipe — he wasn't getting a good hit. Then the pipe broke, and he lacerated his left thumb. By the time he got out onto the field, his thumb wrapped in a towel, the game had already started. He took up the clipboard, his only duty. "I didn't even know what play they were calling," Todd says. "Nobody looked at the shit I wrote down anyway."

At the end of the season, the team had a party. Todd was "gowed out of my mind," meaning that he was "somewhere between a nod and full-on slumber." His weight had dropped to 176 pounds. "I was a celibate heroin monk. I would go downtown, cop, come back to my pad, and not leave till the drugs were gone," he says. "There was no furniture in my place, just a bed and a TV. I wasn't eating. I spent a lot of time in this Astro minivan I had. I'd just climb into the back and fix. My life revolved around dope and my dog."

Now, at the party, Todd became aware that the general manager of the Lions was motioning for him to come over. The GM was a good guy who'd recruited him to come to BC. He shook Todd's hand. "I know we signed you for one year with an option for another year — " he said pregnantly, looking grave.

And then he issued a toothy, gotcha grin: "We'd like to pick up that option!"

"You have to be fuckin' crazy," Todd said. "I can't stay here."

Todd returned to football for the last time in the spring of 2000 — a mercurial stint with the Los Angeles Avengers in the Arena Football League. His first year, he tied the record for most touchdowns in a single game despite undergoing severe heroin withdrawal; after shitting his pants during warm-ups, he came out and threw ten touchdowns to win a game against the Houston Thunderbears. That same year, at age thirty-one, he was named to the all-rookie team. The next season, he became L. A.'s franchise player. The day he picked up his signing bonus, he was busted buying heroin. With him in the truck was $30,000 cash in an envelope. Toward the end of the season, he was ejected from successive games for throwing a clipboard and a hand towel at officials. Finally, he was suspended from the team.

Todd had arrived in his own personal land of Oz, a place were junkies bought and used heroin openly.

"At that point, heroin became my full-time job," Todd says.

By 2004, he was broke and living again on the Balboa Peninsula, haunting the beaches and alleyways of his youth. In the summers, he often lived on the beach, washing at the bathhouse. Sometimes he couch-surfed with friends. Different from many junkies, he seemed to have a knack for being a good guest. Even at his worst, he maintained the sweet and vulnerable quality that makes people want to embrace him. He didn't go to his family's place often. He hated the way Trudi looked at him. At some point, his uncle Craig would accuse him of stealing and Trudi would change the locks.

Because he'd lost his car and license, Todd had trouble scoring heroin. He couldn't afford it, anyway. There was a ton of speed around Newport Beach, though. "People were practically giving it away," he recalls.

When he was high, he loved to skateboard. "It was a way to burn off all that energy that I had from the meth. It was like surfing on fucking concrete. I would skate for eight hours a day. I'd be just carving up and down the street for miles and miles. It was probably the most fun I've ever had on drugs. That and sex. Meth makes you just fucking perv. It turns normal people with some morals into just fucking sick perverts. That's all I wanted to do, you know, is look at porn or create my own."

A ghostly, six-five redhead living on the same tiny peninsula where he grew up so prominently, Todd was an easy mark. In August 2004, he was arrested by Newport Beach police for skateboarding in a prohibited zone. Police found meth and syringes on him. In May 2005, he was rousted from a public bathhouse by police; he fled on his beach cruiser and was apprehended fifteen blocks away. Police found drug paraphernalia in his toiletry kit but no drugs. One of the cops was an old Capo Valley teammate. Todd was charged with violating probation. In June 2005, thanks to twenty-three of his former USC teammates who put up the $4,600 required for him to enter an inpatient treatment program, Todd avoided going back to jail. For the next year, he was in and out of rehab facilities.

At a little past one in the morning on August 26, 2007, a pair of Newport police officers riding in an unmarked minivan spotted Todd, by now thirty-eight years old, skateboarding on the boardwalk. He was carrying a guitar case and wearing a backpack; he had just been to his hook spot. As Todd knew well, skating is not permitted on the boardwalk.

"One cop started running at me. The other one's crossing the boulevard, trying to head me off. I popped off my skateboard, dropped my guitar case, and fucking ran down this alley. One of them yelled: 'Todd! Freeze!' I heard a pop pop pop. I thought they were fucking shooting!" It turned out to be a Taser. The projectile imbedded itself in the lower part of his backpack. "My leg started spasming, but it wasn't too bad. I just kept running." He ended up on a second-floor balcony. "I saw the fucking light come on, and a guy came out, looked at me, and shut the door real fast. I was like, Oh fuck!"

By then there were helicopters with spotlights. He could hear the dogs. "That's when I gave up. I've seen too many people come into fucking jail tore up from dogs. So I just laid down on the fucking ground and they found me."

It was his ninth arrest. He was charged with felony possession of a controlled substance and misdemeanor counts of unauthorized possession of a hypodermic needle and resisting a police officer. He did his second stint at the Farm, where he picked vegetables and repaired irrigation equipment.

Evening in the suburbs, September 2008. The dishes have been put away, the washer in the garage is cycling through another load. A fifteen-year-old boy sits at the dining-room table, doing his honors geometry homework.

Todd saunters into the room. He stands over the kid for a moment, places his large freckled mitt on his shoulder. The knuckles are raw from his part-time job scraping barnacles off the bottoms of boats. It is a tough, physical job. He likes that it tires him out; he always seems to be a little jittery and on edge, generally ill at ease in the world. He wears a wet suit and goggles, uses a long air hose, makes his rounds from motor yacht to sailboat in a dinghy. He'll be down there all alone for a half hour at a time, his bubbles slowly circling the hull, lost in repetitious physical effort, cocooned by the silent, salty water. He compares it to the soothing feeling of heroin.

As of tonight, he's been sober thirteen months. Following his last arrest, he was diverted to a special drug court run by a county judge. Hanging over Todd's head is a suspended sentence of two years in jail. His schedule is nearly as crowded as it was during the summer before ninth grade. Pee testing three times a week. Weekly drug-court sessions, one-on-one therapy, group therapy, sessions with his probation officer, thrice-weekly AA meetings. If he completes the program, in another eighteen months, he could have his felonies dismissed or reduced, opening up his opportunity for coaching at a public school. With all the responsibilities, he is expected to cobble together a new life. It is a difficult task.

Besides the barnacle scraping, for which he makes about forty dollars a boat, Todd leads a weekly group meeting at a rehab facility; people seem to respond to both his celebrity status and his easygoing manner. He's also been painting murals in people's houses. There is a local gallery that wants to show his work; a Web site is planned for direct buying. His other source of income is private coaching. Over the past year, he's become known as somewhat of a "quarterback whisperer." This past summer he worked with Jordan Palmer, brother of Carson; both Palmers are on the roster at Cincinnati. USC coach Pete Carroll recently told him he'd try to get Todd some work next summer at a football camp. There will be an interview for a job as offensive coordinator at a local junior college. Right now, Todd has four students, kids of varying ages. All of them have promise; Jordan Greenwood is one of his most talented.

"Dude. You got a minute?"

Jordan looks up attentively. He is five foot eleven and a half, 150 pounds. He's a freshman at Orange Lutheran, one of the schools that competes in the Trinity League against Todd's old team Mater Dei. Jordan started playing tackle football at age eight. He has always been a super athlete. One time in a soccer game, he had three goals in the first ten minutes.

About a year ago, Jordan was referred to Marv. Todd was brought in on day two. Though he hadn't been sober long, Todd watched Jordan throw and thought to himself, I could really help this kid. The first order of business: completely remake Jordan's throw — which nearly gave Jordan's father a heart attack. For the next six months, every night, Jordan had to stand in front of the mirror and repeat the new motion a thousand times. Each rep had to be perfect. It was up to Jordan; nobody could do it for him.

The first three exhibition games of the new season, the freshman-team coach rotated four quarterbacks. Fleet of foot, Jordan was perfect for the veer offense; he scored fifteen touchdowns, including a seventy-yard run against an inner-city team. Then came the fourth exhibition. The entire extended Greenwood family was on hand to watch. Jordan did not play.

Now, after a nice dinner of strip steaks and salmon and double-stuffed potatoes, with all the other adults out of the room, Todd folds himself into the chair next to Jordan. His orange hair is not so bright anymore, like a colorful curtain faded over the years by the sun.

"What's the worst part of your experience over there at Orange?" Todd asks.

Jordan drums his pencil on the open pages of his math book. "I don't know," he says.

"Not playing?"

Jordan makes eye contact. "Yeah, mostly."

"What else?"

Shrug. "I dunno." This is the biggest thing in his life. You can tell he's trying not to cry.

"Listen, dude," Todd says, as warm a dude as was ever uttered. "Things can look pretty overwhelming right now because you're so young, but believe me, you can have a great career — possibly at Orange Lutheran. I wouldn't cash my chips and be bitter just yet. Some days, stuff just looks all wrong — take it from me. You're gonna be fine. You just have to believe in yourself."

Jordan nods his head, brightening.

Todd gives him a little shove. Next game, Jordan will run for three touchdowns and throw for another. Before the season is over, he'll be promoted to JV and win the team's most valuable offensive player award.

Todd and Marv Marinovich are at a self-storage facility in San Juan Capistrano. Most of Marv's equipment is inside, odd-looking machines and exercise stuff. Somehow, in the haste of the initial rental, the key was lost. After attempting to drill out the lock — it looks so easy in the movies — they await a locksmith.

Todd is squatting on the hot asphalt like a gang member in a prison yard. Marv is standing against the building in a sliver of shade. Ending his seventh decade, he looks twenty years younger. He lives alone, eats only organic food. Despite his ferocious reputation, he seems a sweet man who loves Todd very much. After two divorces, he has only Todd and Traci, who lives a couple hours away, and Mikhail, his son with his second wife, a former dancer. Mikhail is a six-foot-four sophomore defensive end at Syracuse, about as far as you can get from OC. Last year Mikhail made news when he was arrested for getting drunk and breaking into the college's gym equipment room with a friend. Todd advised: "Don't be stupid. You're a Marinovich. You have a target on your back."

Some days, stuff just looks all wrong — take it from me.

Marv's stuff is in storage because he was asked to leave the private high school out of which he'd been working for nearly two years. There was a beef with his young partner. After a display of temper, Marv was asked to vacate by school authorities. The partner stayed. Todd and a friend went with a U-Haul to claim Marv's equipment.

Now, because it's the end of the month, they have to pay or move. A friend of Todd's has volunteered a garage. Todd has taken care of everything. Since he's been straight, he's spent a lot of time helping Marv. He's helping him get his driver's license back — a long tale of red tape. He helped him buy a computer. He's helping with visits to the doctor; there are indications of heart arrhythmia. "All those years I was so out of it. It feels good to be the one helping," Todd says. "He's always been there for me."

When Todd was born, he was listed as Marvin Scott Marinovich on his birth certificate. Trudi changed it a few years later to Todd Marvin. Later — an inside joke after a long day of training — Marv started calling his son Buzzy, after Buzzie Bavasi, the legendary Dodgers general manager. For some reason, Todd began calling Marv Buzzy, too. Nowadays, when Marv calls Todd's cell phone — Todd's ringtone is the opening bars of the Monday Night Football theme song — Todd will pick up and say, "Hey, Buzzy, what's up?"

Now, waiting for the locksmith, needing talk to fill the time, Todd begins telling Marv about the art-history course he's taking at Orange Coast College. The other night in class, Todd explains, they were learning about dadaism, the anti-art movement born in Switzerland during World War I. One of the icons of the movement was this dude named Marcel Duchamp. He did a cool painting called Nude Descending a Staircase. "When he was coming up, his older brothers and his friends were the ones recognized as the famous painters. They thought Marcel sucked," Todd explains. "But in the end, everybody recognized that Marcel was the true master."

"After he was dead, I'm sure," Marv says.

"When I heard that," Todd continues, ignoring his father's comment, "the first thing I thought of was you, Buzzy. Someday people will realize what a genius you are."

Marv looks at him. He's not sure if Todd is goofing or serious. He raises his thick eyebrows archly. "Have you been drinking something?" he asks.

And then the two of them, Buzzy and Buzzy, share a big laugh.

Driving north on I-5, past the rugged mountains of Camp Pendleton, Todd and I are returning from off-loading Marv's stuff. The large U-Haul truck judders wildly on the uneven asphalt. Even at fifty miles per hour in the slow lane, the ride is torturous. It has been a full day; the mood in the cab could rightfully be called slaphappy. Todd has noticed that if he sings a note and holds it, the pounding of the road will make his voice quaver rhythmically. It is a silly, joyful thing that turns the discomfort of the ride upside down. I remember my son doing the same on this stretch of road when he was about five.

You could say Todd missed his childhood. Sports took away his first twenty years. Then drugs took the second twenty, the decades of experience and personal growth that shape most men as they near forty, which Todd will turn this upcoming July 4. When Todd was young, Trudi used to tell him that the Independence Day fireworks were all for him. Today she estimates that since he's been straight, these past thirteen months, Todd has matured from an emotional age of about sixteen to maybe twenty-five, the same age as his fiancée.

Alix is an OC girl with pretty blue eyes. She is pregnant. They are expecting a boy. They plan to name him Baron Buzzy Marinovich. They have cleaned out the Chief's trophy room on the first floor of the beach house and made a little nest for themselves, complete with a new mini kitchen where the bar used to be.

Todd says he's finished with drugs — the frantic hustle, the lies, the insidious need, the way the world perceives you as a loser. Each time he went to jail, he walked the gantlet of deputies, many of them former high school football players. "You had everything and you threw it away," they said. It was hard to hear. He knows they were telling the truth.

Three months from now, in early February, feeling pressure from all directions — the deaths within two weeks of his uncle Craig and grandma Virginia, the upcoming gallery show, Marv's health problems, a new life with his fiancée, questions about his future — he will drive on a Sunday afternoon to his old hook spot in Santa Ana and buy some black tar. As soon as he smokes the first hit, he will throw the dope out the window and call his probation officer, then drive directly to the county offices to give himself up. Sixteen months of sobriety lost in an instant. His penalty will be one week at the Farm; it could have been two years. As he drives across town to surrender, he will see in his mind a picture of Alix, the swell of her belly. He wants to be a father to his son.

"I'm gonna get through this program," he says now, his voice quavering comically as we bounce up the road in the U-Haul. "The day is coming when I'm not gonna have to piss in a fucking cup."

From the driver's seat, sensing his good mood, I ask: "How much effect do you think that Marv and sports and all contributed to you turning to drugs?" I'd been saving this line of questioning since our first interview, six months earlier. "If you look at your life, it's interesting. It appears that to get out of playing, you sort of partied away your eligibility. It's like you're too old to play now, so you don't have to do drugs anymore. Has the burden been lifted?"

Todd looks out the windshield down the road. The truck bounces. Thirty full seconds pass.

"I don't know how to answer that," Todd says at last. "I really have very few answers."

"That's kind of what it seems like. A little."

Twenty seconds.

"No thoughts?"

"I think, more than anything, it's genetic. I got that gene from the Fertigs — my uncle, the Chief. They were huge drinkers. And then the environment plays a part in it, for sure."

He lights another Marlboro Red, sucks down the first sweet hit. He rides in silence the rest of the way home.

Mike Sager is a bestselling author and award-winning reporter who's been a contributor to Esquire for thirty years.