The familiar fear of The Evil Within (original) (raw)

Hands-on with Shinji Mikami's return to survival horror.

I'm trapped in a strange and sinister place, knee deep in gore and a vindictive supernatural force is toying with me for reasons I don't understand. It's strangely comforting. That's the curious contradiction at the bloodied and disembodied heart of The Evil Within, the new game from Resident Evil creator Shinji Mikami, which publisher Bethesda Softworks has just announced will be released on 24th October in Europe, a couple of months later than previously expected.

The location isn't Raccoon City, and the publisher isn't Capcom, but the similarities to Mikami's beloved blockbuster creation are impossible to shake off once you're playing. For fans left jaded by the recent Resident Evil sequels, this can only come as good news. If you want to pretend this is the follow-up to Resident Evil 4 that we never got, you really wouldn't have to squint very hard to sell the fantasy. From mechanics to aesthetics, it's a clear continuation of Mikami's distinctive style.

For the purposes of our strictly limited demo, we're given access to two separate chunks of the game. The first comes from Chapter 4, we're told, and finds our hero, detective Sebastian Castellanos leading a doctor on a search for a missing patient in the blood-stained hospital where the game begins.

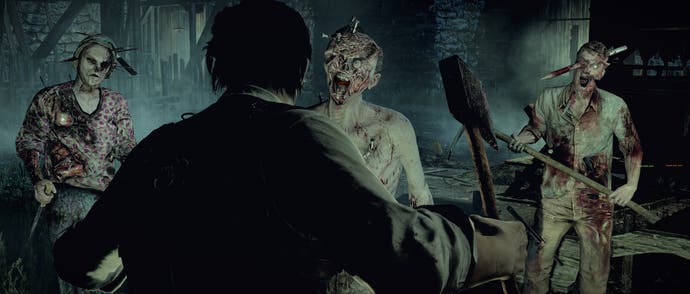

Upon finding the patient in question, we get our first encounter with the mangled and disfigured enemies who roam the game as one of them shambles into the room, right on cue, blocking the only exit. Combat is familiar enough, but slightly tougher than survival horror games of the past. Melee attacks are good only for creating distance. It takes more shots than you expect to take an enemy down - unless you get lucky with a close-quarters blast - and even then there's a chance they'll get up again. The only way to be sure is to burn the body with one of your limited supply of matches.

The dialogue is as wonderfully cheesy and stilted as any Resident Evil game. "We must be collectively losing our minds!" gasps Castellanos at one point.

That supply is very limited, by the way. Castellanos must have tiny fingers or small pockets, since he can only carry five matches at a time. He's not exactly fighting fit either, having to pause to get his breath back after running for just five seconds even if a hellish monster is at his heels. We are promised that his abilities can be upgraded, however, thanks to vials of green goop sprinkled around the environment. That function sadly isn't implemented in this early demo, so we'll just have to hope it will allow Castellanos to get his head around concepts like cardiovascular exercise and those newfangled 'matchboxes' that everyone keeps going on about.

There's more combat to come. Not long after finding the patient with the doctor, Castellanos is separated from them when reality gives a shudder, creating walls where there was previously a corridor and leaving our hero alone. There's a fair bit of this sort of trickery on display - using the game engine to alter 'reality' while you're looking the other way - and as crude as the trick is, it remains a monstrously effective one.

There's little time to be bamboozled, mind you, as Castellanos is then dumped into what looks like a charnel pit, waist deep in gore. There are booby traps here - tripwires and proximity explosives - which can be defused or dismantled with some quick timing. This gives up some scrap for ammo upgrades, though this too is a feature not available in the demo.

Mostly, this section exists to show the ways in which you can use the environment to your advantage. When you try to leave the area, a large group of enemies spawns - too many to be comfortably defeated with your available ammo. There are several adjoining rooms, various levers which can deposit oil barrels from on high, not to mention some ladders and elevated routes. It's a lot like the village square standoff from the start of Resi 4, frankly, as you learn to leave traps unmolested to catch enemies, and use your superior agility to outmanoeuvre the shambling foes.

Your most powerful weapon is the Agony Crossbow, which fires custom craftable ammo with various status effects.

Survive this encounter, and after a bit more exploring we come across what looks like a boss enemy. This sickening spider-crab thing can't be killed - another important lesson for The Evil Within, that discretion is the better part not only of valour, but of not being ripped to pieces. You run, you escape by the skin of your teeth.

It's a well-paced bit of action, but taken together with the blood pit battle where exploding barrels and headshots win the day, it feels more like recent action-skewed survival horror than the return to genre purity we've been hoping for.

That comes in the second, much larger, section of the game we get to play. This is Chapter 8 - "The Cruellest Intentions" according to the subtitle - and it's where the game really starts to tweak fan expectations. You're in a creaky old mansion. There's a door locked by an arcane puzzle which requires you to find three secret areas. There are clues in paintings and a safe that has had both its tumblers removed and hidden for no apparent reason. There are even flashbacks to the murky history of the dysfunctional medical family that once lived here, a grand gothic melange of sociopathic children, cruel parents and nasty experiments.

It is, let's face it, Resident Evil. Quite blatantly. And quite brilliantly as well. It's here that I really start to enjoy myself, even as I'm feeling the snug embrace of nostalgia. It's an odd feeling - the game is deliciously creepy, but never really all that scary because so much feels familiar. It's like visiting a theme park haunted house - you're always anticipating the jumps with a smile, rather than dreading them.

Health top-ups come in syringes but, very rarely, you'll find a large medkit which increases your available health but leaves your vision swimming for a few minutes.

The attempts at gross horror stuff feel almost quaint, as in the mini-puzzles where you must insert a probe into the correct region of the brain in living, moaning disembodied heads. 'Puzzles' is probably a rather ambitious term, given that there's a recorded voiceover and accompanying diagram to show you exactly what to do, but it's amusingly grotesque and a nice change of pace from the usual survival horror tropes of finding medallions and pushing statues. It's more theatre than challenge, but it's fun in the same way as as a rubber Halloween mask; horror as a cliché that we willingly embrace.

Some aspects don't work quite as well. You can apparently kill unaware enemies with an instant stealth kill, but I rarely found enemies who were obligingly facing the right way, and when I did they still seemed to turn and attack no matter how slowly I crept up on them. There are also sporadic moments where a hooded apparition appears and begins to stalk you. You can hide from this sinister phantom by cowering in cupboards or sliding under beds, or you can just as easily evade it by running around the room in a circle until it disappears.

The Evil Within is a promising game, then, but one that still has a fair bit to prove. In trying so nakedly to reset the survival horror genre back to the way it was in the 1990s, it gets an awful lot right in terms of atmosphere and design, but also inherits more than a few curious quirks and awkward controls. Backtracking through rooms looking for doors I'd missed, or running away and quick-turning to pop off headshots on dim-witted monsters; these are ideas that are more than a little threadbare in 2014. Much will depend on how elements such as character upgrades and other systems change the balance, and how the game can escalate and evolve its inherited DNA over the course of the story. There's a definite sense of a game that is willing to change its pace and gameplay style, slipping from action to cautious exploration to light puzzling frequently enough that it can still seem fresh.

Survival horror depends on limiting your resources, but The Evil Within seems fairly generous with ammo on standard difficulty. More than once I couldn't pick up more bullets because I'd stockpiled so many.

I'm definitely more excited for The Evil Within than I was last year, and experiencing it first-hand (in a curtained booth in a claustrophobic darkened room) makes me realise just how much I've missed the true survival horror experience, warts and all. There's stuff here that will have fans cheering, and it should certainly give Capcom pause for thought as it works out what to do with the tarnished Resident Evil brand.

Yet I do still find myself wishing that maybe its best elements weren't also the ones that are backwards-looking, fixated on recreating and repairing the genre's past rather than building for its future. The Evil Within adheres so closely to classic genre elements that it risks becoming the equivalent of the Rolling Stones taking the stage to play Satisfaction as an encore, given weight by our shared history and love for what came before but a comforting expectation rather than a blast of invigorating innovation.

There's a lot more game still to be revealed, however, and if the worst-case scenario is that The Evil Within simply turns out to be the first really good survival horror game in 10 years, well, that's not exactly the stuff of nightmares, is it?

This preview is based on a trip to a press event in Los Angeles. Bethesda paid for travel and accommodation.