Culture of Azerbaijan - history, people, traditions, women, beliefs, food, customs, family, social (original) (raw)

- Countries and Their Cultures

- A-Bo

- Culture of Azerbaijan

Culture Name

Azerbaijani, Azeri

Alternative Names

Azerbaijani Turkish, Azeri Turkish. The country name also is written Azerbaidzhan, Azerbaydzhan, Adharbadjan, and Azarbaydjan in older sources as a transliteration from Russian. Under the Russian Empire, Azerbaijanis were known collectively as Tatars and/or Muslims, together with the rest of the Turkic population in that area.

Orientation

Identification. Two theories are cited for the etymology of the name "Azerbaijan": First, "land of fire" ( azer , meaning "fire," refers to the natural burning of surface oil deposits or to the oil-fueled fires in temples of the Zoroastrian religion); second, Atropaten is an ancient name of the region (Atropat was a governor of Alexander the Great in the fourth century B.C. ). The place name has been used to denote the inhabitants since the late 1930s, during the Soviet period. The northern part of historical Azerbaijan was part of the former Soviet Union until 1991, while the southern part is in Iran. The two Azerbaijans developed under the influence of different political systems, cultures, and languages, but relations are being reestablished.

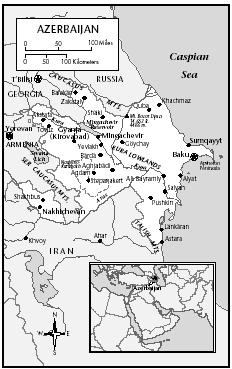

Location and Geography. The Azerbaijan Republic covers an area of 33,891 square miles (86,600 square kilometers). It includes the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region, which is inhabited mostly by Armenians, and the noncontiguous Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, which is separated from Azerbaijan by Armenian territory. Nakhchivan borders on Iran and Turkey to the south and southwest. Azerbaijan is on the western shore of the Caspian Sea. To the north it borders the Russian Federation, in the northwest Georgia, in the west Armenia, and in the south Iran. Half the country is covered by mountains. Eight large rivers flow down from the Caucasus ranges into the Kura-Araz lowland. The climate is dry and semiarid in the steppes in the middle and eastern parts, subtropical in the southeast, cold in the high mountains in the north, and temperate on the Caspian coast. The capital, Baku, is on the Apsheron peninsula on the Caspian and has the largest port.

Demography. The population of the Azerbaijan Republic has been estimated to be 7,855,576 (July 1998). According to the 1989 census, Azeris accounted for 82.7 percent of the population, but that number has increased to roughly 90 percent as a result of a high birthrate and the emigration of non-Azeris. The Azerbaijani population of Nagorno-Karabakh and a large number of Azeris (an estimated 200,000) who had been living in Armenia were driven to Azerbaijan in the late 1980s and early 1990s. There are about one million refugees and displaced persons altogether. It is believed that around thirteen million Azeris live in Iran. In 1989, Russians and Armenians each made up 5.6 percent of the population. However, because of anti-Armenian pogroms in Baku in 1990 and Sumgait in 1988, most Armenians left, and their population (2.3 percent) is now concentrated in Nagorno-Karabakh. Russians, who currently make up of 2.5 percent of the population, began to leave for Russia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The number of Jews decreased as they left for Russia, Israel, and the United States in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Numerous ethnic groups (up to ninety) of the former Soviet Union are represented in small numbers (Ukrainians, Kurds, Belorussians, Tatars). Other groups with a long history of settlement in Azerbaijan include the Persian-speaking Talysh and the Georgian-speaking Udins. Peoples of Daghestan such as the Lezghis and Avars make up 3.2 percent of the population, with most of them living in the north. Fifty-three percent of the population is urban.

Linguistic Affiliation. Azeri (also referred to as Azeri Turkish) or Azerbaijani is a Turkic language in the Altaic family; it belongs to the southwestern Oguz group, together with Anatolian Turkish, Turkmen, and Gagauz. Speakers of these languages can understand each other to varying degrees, depending on the complexity of the sentences and the number of loan words from other languages. Russian loan words have entered Azeri since the nineteenth century, especially technical terms. Several Azeri dialects (e.g., Baku, Shusha, Lenkaran) are entirely mutually comprehensible. Until 1926, Azeri was written in Arabic script, which then was replaced by the Latin alphabet and in 1939 by Cyrillic. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Azerbaijan and other Turkic-speaking former Soviet republics reintroduced the Latin alphabet. However, the main body of modern Azeri literature and educational material is still in Cyrillic, and the transition to the Latin alphabet is a time-consuming and expensive process. The generations that learned Russian and read Azeri in Cyrillic still feel more comfortable with Cyrillic. During the Soviet period, linguistic Russification was intensive: although people referred to Azeri as their native tongue, the language many people in the cities mastered was Russian. There were both Azeri and Russian schools, and pupils were supposed to learn both languages. Those who went to Russian schools were able to use Azeri in daily encounters but had difficulty expressing themselves in other areas. Russian functioned as the lingua franca of different ethnic groups, and with the exception of rural populations such as the Talysh, others spoke very little Azeri. Roughly thirteen languages are spoken in Azerbaijan, some of which are not written and are used only in everyday family communication. Azeri is the official language and is used in all spheres of public life.

Symbolism. Azerbaijan had a twenty-three-month history of statehood (1918–1920) before the institution of Soviet rule. The new nation-state's symbols after the dissolution of the Soviet Union were heavily influenced by that period. The flag of the earlier republic was adopted as the flag of the new republic. The flag has wide horizontal stripes in blue, red, and green. There is a white crescent and an eight-pointed star in the middle of the red stripe. The national anthem forcefully portrays the country as a land of heroes ready to defend their country with their blood. The sentiments associated with music in Azerbaijan are very strong. Azeris regard themselves as a highly musical nation, and this is reflected in both folk and Western musical traditions.

Azerbaijan

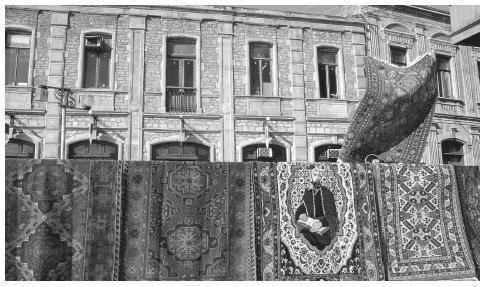

To show pride in country, Azeris first refer to its natural resources. Oil is at the top of the list, and the nine climatic zones with the vegetables and fruits that grew in them also are mentioned. The rich carpet-weaving tradition is a source of pride which is used to highlight the artistic sensibilities of carpet weavers (most of the time women) and their ability to combine various forms and symbols with natural colors. Hospitality is valued as a national characteristic, as it is in other Caucasus nations. Guests are offered food and shelter at the expense of the host's needs, and this is presented as a typical Azeri characteristic. The use of house metaphors was widespread at the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict: Armenians were regarded as guests who wanted to take possession of one of the rooms in the host's house. Ideas of territorial integrity and the ownership of territory are very strong. Soil—which in Azeri can refer to soil, territory, and country—is an important symbol. Martyrdom, which has a high value in the Shia Muslim tradition, has come to be associated with martyrdom for the Azeri soil and nation. The tragedy of the events of January 1990, when Russian troops killed nearly two hundred civilians, and grief for those who died in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, have reinforced the ritual activity attached to martyrdom.

Azeri women and their characteristics are among the first ethnic markers (attributed characteristics) that differentiate Azeris as a nation. Their moral values, domestic abilities, and role as mothers are pointed out in many contexts, especially in contrast to Russians.

The recent history of conflict and war, and thus the suffering evoked by those events in the form of deaths, the misery of displaced persons, and orphaned children, has reinforced the idea of the Azeri nation as a collective entity.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Azerbaijan was inhabited and invaded by different peoples throughout its history and at different times came under Christian, pre-Islamic, Islamic, Persian, Turkish, and Russian influence. In official presentations, the Christian kingdom of Caucasian Albania (which is not related to Albania in the Balkans) and the state of Atropatena are regarded as the beginnings of the formation of Azerbaijani nationality. As a result of Arab invasions, the eighth and ninth centuries are seen as marking the start of Islamization. The invasions of the Seljuk Turkish dynasty introduced the Turkish language and customs. From the thirteenth century onward, it is possible to find examples of literature and architecture that today are considered important parts of the national heritage. The local dynasty of Shirvan shahs (sixth to sixteenth centuries) left a concretely visible mark in Azeri history in the form of their palace in Baku. Until the eighteenth century, Azerbaijan was controlled by neighboring powers and was invaded repeatedly. In the nineteenth century, Iran, the Ottoman Empire, and Russia took an interest in Azerbaijan. Russia invaded Azerbaijan, and with the 1828 treaty borders (almost identical to the current borders), the country was divided between Iran and Russia. The rich oil fields in Baku that were opened in the midnineteenth century attracted Russians, Armenians, and a few westerners, such as the Nobel brothers. The vast majority of the oil companies were in Armenian hands, and many Azeri rural inhabitants who came to the city as workers joined the socialist movement. Despite international solidarity between the workers during strikes (1903–1914), tension existed between Armenian and Azeri laborers, with the Azeris being less skilled and thus worse paid. This discontent exploded in bloody ethnic conflicts in the period 1905–1918. The fall of the Russian monarchy and the revolutionary atmosphere fed the development of national movements. On 28 May 1918, the Independent Azerbaijan Republic was established. The Red Army subsequently invaded Baku, and in 1922 Azerbaijan became part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. In November 1991, Azerbaijan regained its independence; it adopted its first constitution in November 1995.

National Identity. In the early twentieth century, secular Azeri intellectuals tried to create a national community through political action, education, and their writings. Ideas of populism, Turkism, and democracy were prevalent in that period. As a reaction to the colonial regime and exploitation that was expressed in ethnic terms, the formation of Azeri national identity had elements of both Islamic and non-Islamic traditions as well as European ideas such as liberalism and nationalism. The idea of an Azeri nation also was cultivated during the Soviet period. The written cultural inheritance and the various historical figures in the arts and politics reinforced claims to independent nationhood at the end of the Soviet regime. During the decline of the Soviet Union, nationalist sentiment against Soviet rule was coupled with the anti-Armenian feelings that became the main driving force of the popular movements of national reconstruction.

Ethnic Relations. Since the late 1980s, Azerbaijan has been in turmoil, suffering interrelated ethnic conflict and political instability. Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians had raised the issue of independence from Azerbaijan a number of times since 1964, and those claims became more forceful in the late 1980s. Armenia supported the Nagorno-Karabakh cause and expelled about 200,000 Azeris from Armenia in that period. Around that time, pogroms took place against Armenians in Sumgait (1988) and Baku (1990), and more than 200,000 Armenians subsequently left the country. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict turned into a protracted war, and atrocities were committed by both sides until an enduring cease-fire was agreed to in 1994. The massacre of the village of Khojaly in 1992 by Armenians is engraved in Azeri memory as one of the worst aggressive acts against Azeri civilians. Azeris who lived in Nagorno-Karabakh territory were driven out during the war. They are now among the refugees and displaced persons in Azerbaijan and make the conflict with Armenia visible. The Lezgis and

Carpets for sale in front of a building in Baku. Traditional carpet weaving is a large component of Azerbaijani commerce.

Talysh also made demands for autonomy, but despite some unrest, this did not result in extensive conflicts. Azeris in Iran have been subject to strictly enforced assimilation policies. Although the opening of the borders has nurtured economic and cultural relationships between the two Azerbaijans, Iranian Azeris do not have much cultural autonomy.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

There are various dwellings in different regions. Traditionally, people in towns lived in quarters ( mahallas ) that developed along ethnic lines. Modern Azerbaijan adopted the Soviet style of architecture; however, Baku retains a Maiden Tower and an old town criscrossed with narrow streets as well as examples of a mixture of European styles in buildings that date back to the beginning of the twentieth century. These edifices usually were built with funds from the oil industry.

Soviet-era governmental buildings are large and solid with no ornamentation. Residential complexes built in that period usually are referred to as "matchbox architecture" because of their plain and anonymous character. Public space in bazaars and shops is crowded, and people stand close to each other in lines.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. There are regional differences in the selection and preparation of food resulting from the availability of agricultural products and membership in different ethnic groups. A mixture of meat and vegetables and various types of white bread constitute the main foods. In rural areas, there is a tradition of baking flat white bread ( churek , lavash , tandyr ). Kufte bozbash (meat and potatoes in a thin sauce) is a popular dish. Filled pepper and grape leaves and soups also are part of daily meals. Different types of green herbs, including coriander, parsley, dill, and spring onions, are served during meals both as a garnish and as salad. Pork is not popular because of Islamic dietary rules, but it was consumed in sausages during the Soviet period. The soup borsch and other Russian dishes are also part of the cuisine. Restaurants offer many varieties of kebabs and, in Baku, an increasingly international cuisine. Some restaurants in the historic buildings of Baku have small rooms for family and private groups.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Pulov (steamed rice) garnished with apricots and raisins is

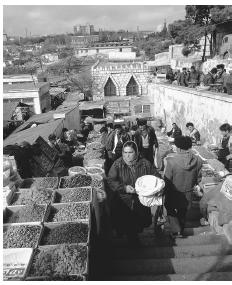

A dried fruit market in Baku.

a major dish at ritual celebrations. It is eaten alongside meat, fried chestnuts, and onions. During the Novruz holiday, wheat is fried with raisins and nuts ( gavurga ). Every household is supposed to have seven types of nuts on a tray. Sweets such as paklava (a diamond-shaped thinly layered pastry filled with nuts and sugar) and shakarbura (a pie of thin dough filled with nuts and sugar) are an indispensable part of celebrations. At weddings, pulov and various kebabs are accompanied by alcohol and sweet nonalcoholic drinks ( shyra ). At funerals, the main course is usually pulov and meat, served with shyra and followed by tea.

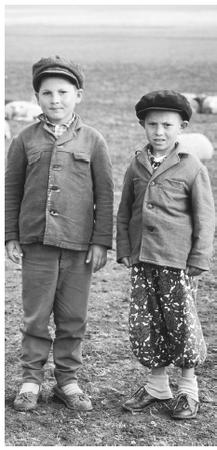

Basic Economy. Azerbaijan has a rich agricultural and industrial potential as well as extensive oil reserves. However, the economy is heavily dependent on foreign trade. The late 1980s and 1990s saw intensive trade with Russia and other countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States. Turkey and Iran have begun to be important trade partners. About one-third of the population is employed in agriculture (producing half the population's food requirements); however, with 70 percent of agricultural land dependent on poorly developed irrigation systems and as a result of delays in the privatization process, agriculture is still inefficient and is not a major contributor to the economy. People in rural areas grew fruits and vegetables in small private gardens for subsistence and sale during the Soviet period. The major agricultural crops are cotton, tobacco, grapes, sunflowers, tea, pomegranates, and citrus fruits; vegetables, olives, wheat, barley, and rice also are produced. Cattle, goats, and sheep are the major sources of meat and dairy products. Fish, especially sturgeon and black caviar, are produced in the Black Sea region, but severe pollution has weakened this sector.

Land Tenure and Property. In the Soviet period, there was no private land as a result of the presence of state-owned collective farms. As part of the general transition to a market economy, privatization laws for land have been introduced. Houses and apartments also are passing into private ownership.

Commercial Activities. There is a strong carpet-weaving tradition in addition to the traditional manufacturing of jewelry, copper products, and silk. Other major goods for sale include electric motors, cabling, household air conditioners, and refrigerators.

Major Industries. Petroleum and natural gas, petrochemicals (e.g., rubber and tires), chemicals (e.g., sulfuric acid, and caustic soda), oil refining, ferrous and nonferrous metallurgy, building materials, and electrotechnical equipment are the heavy industries that make the greatest contribution to the gross national product. Light industry is dominated by the production of synthetic and natural textiles, food processing (butter, cheese, canning, wine making), silk production, leather, furniture, and wool cleaning.

Trade. Other countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States, Western European countries, Turkey, and Iran are both export and import partners. Oil, gas, chemicals, oil field equipment, textiles, and cotton are the major exports, while machinery, consumer goods, foodstuffs, and textiles are the major imports.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. The urban merchant class and industrial bourgeoisie of the pre-Soviet era lost their wealth under the Soviet Union. The working class in the cities usually retained rural connections. The most significant social stratification criterion is an urban versus rural background, although the educational opportunities and principles of equality introduced in the Soviet period altered this pattern to some extent. Russians, Jews, and Armenians were mostly urban white-collar workers. For Azerbaijanis,

Workers on an offshore drill in the Caspian Sea dismantle a drilling pipe.

education and family background were vital to social status throughout the pre- and post-Soviet period. Higher positions in government structures provided political power that was accompanied by economic power during the Soviet era. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, wealth became a more important criterion for respect and power. Refugees and displaced persons with a rural background now can be considered the emergent underclass.

Symbols of Social Stratification. As in the socialist era, Western dress and urban manners usually have a higher status than does the rural style. During the Soviet period, those who spoke Russian with an Azeri accent were looked down on, since this usually implied being from a rural area or having gone to an Azeri school. By contrast, today the ability to speak "literary" Azeri carries a high value, since it points to a learned family that has not lost its Azeri identity.

Political Life

Government. According to the constitution, Azerbaijan is a democratic, secular unitary republic. Legislative power is implemented by the parliament, Milli Mejlis (National Assembly; 125 deputies are directly elected under a majority and proportional electoral system for a term of five years, most recently 1995–2000). Executive power is vested in a president who is elected by direct popular vote for five years. The current president Heydar Aliyev's term will end in October 2003. The Cabinet of Ministers is headed by the prime minister. Administratively, the republic is divided into sixty-five regions, and there are eleven cities.

Leadership and Political Officials. Since the late 1980s, the attainment of leadership positions has been strongly influenced by social upheaval and opposition to the existing system and its leaders. However, the network based on kin and regional background plays an important role in establishing political alliances. The system of creating mutual benefits through solidarity with persons with common interests persists.

Generally, political leaders assume and/or are attributed roles described in family terms, such as the son, brother, father, or mother of the nation. Young males have been a source of support both for the opposition and for the holders of powers. The ideals of manhood through bravery and solidarity were effective in securing popular support for different leaders in the 1980s. Personal charisma plays an important role, and politics is pursued at a personal level. There are about forty officially registered

Two young shepherds. Cattle, goats, and sheep are major agricultural products.

parties. The largest movement toward the end of the Soviet era was the Azerbaijani Popular Front (APF), which was established by intellectuals from the Academy of Sciences in Baku; members of the APF established several other parties later. The chairman of the APF became president in 1992 but was overthrown in 1993. Currently, the APF has both nationalist and democratic wings. The Musavat (Equality) Party has the backing of some intellectuals and supports democratic reforms, the National Independence Party supports market reforms and an authoritarian government, and the Social Democratic Party favors the cultural autonomy of national and cultural minorities and democratization. All these parties are opposed to President Heydar Aliyev's New Azerbaijan Party because of the undemocratic measures taken against their members and in the country at large. The other major parties are the Azerbaijan Liberal Party, Azerbaijan Democratic Party, and Azerbaijan Democratic Independence Party.

Social Problems and Control. According to the constitution, the judiciary exercises power with complete independence. Citizens' rights are guaranteed by the constitution. However, as a result of the uncertainties of the current transitional period, the legacy of the Soviet judicial system, and the authoritative measures taken by power holders, the implementation of legal rules is in practice a source of tension. This means that state organs can break the law by committing actions such as election fraud, censorship, and the detention of protesters. Given the prevalence of white-collar crime affecting investments, savings funds, and financial institutions, the large number of refugees and displaced persons with limited resources has resulted in various illegal business dealings. For example, recent years have seen considerable drug trafficking to Russia and the smuggling of various goods and materials. Despite improvements, people have little faith that they will receive a fair trial or honest treatment unless they belong to the right circles. The ideas of shame and honor are used in evaluating and hence controlling people's actions. Family and community opinion impose limitations on actions, but this also leads to clandestine dealings.

Military Activity. Azerbaijan has an army, navy, and air force. Defense expenditures for the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict placed a sizable burden on the national budget. The official figures for defense spending were around $132 million in 1994.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

There are laws providing for social security for the disabled, pensions, a guaranteed minimum wage, compensation for low-income families with children, grants for students, and benefits for war veterans and disabled persons (e.g. reduced fares on public transport etc.). However, the level of social benefits is very low. National and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are involved in aid work for displaced persons, especially children.

Nongovernmental Organizations and Other Associations

Most NGOs concentrate on charity, mainly for displaced persons and refugees and focus on human rights, minority issues, and women's problems (e.g., the Human Rights Center of Azerbaijan and the Association for the Defense of Rights of Azerbaijan Women). Depending on their specialties, these organizations collect information and try to collaborate with international organizations to support people financially, politically, and socially.

Gender Roles and Statuses

Division of Labor by Gender. Many women were employed outside the home as a result of Soviet policies, but they have traditionally played a secondary role in supporting the family economically. Men are considered the main breadwinners. There are no restrictions on women's participation in public life, and women are active in politics in the opposition and ruling parties. However, their number is limited. Rural women's participation in public life is less common.

The Relative Status of Women and Men. With few exceptions, socially and politically powerful women at the top levels have male supporters who help them maintain their positions. Although professional achievement is encouraged, women are most respected for their role as mothers. Women in rural areas usually control the organization of domestic and ritual life. There is a higher degree of segregation between female and male activities and between the social spaces where they gather.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Even in rural areas, marriages increasingly are arranged in accordance with the partners' wishes. In some cases, girls in rural areas may not have the right to oppose a candidate chosen by their parents; it is also not unusual for parents to disapprove of the chosen partner. Marriages between Azeri girls and non-Muslim non-Azeris (Russians, Armenians) in the Soviet period were very rare, but Western non-Muslims apparently now have a different status. Men, by contrast, could marry Russians and Armenians more easily. Both men and women marry to have children and bring up a family, but economic security is another important concern for women. In addition to the civil marriage ceremony, some couples now go to a mosque to get married according to Islamic law.

Domestic Unit. The basic household unit is either a nuclear family or a combination of two generations in one household (patrilocal tendency). In urban areas, mainly as a result of economic difficulties, newlyweds live with the man's parents or, if necessary, the woman's parents. The head of the household is usually the oldest man in the family, although old women are influential in decision making. In rural areas, it is possible for an extended family to live in one compound or house shared by the sons' families and their parents. Women engage in food preparation, child rearing, carpet weaving, and other tasks within the compound, while men take care of the animals and do the physically demanding tasks.

Inheritance. Inheritance is regulated by law; children inherit equally from their parents, although males may inherit the family house if they live with their parents. They then may make arrangements to give some compensation to their sisters.

Kin Groups. Relatives may live nearby in rural areas, but they usually are dispersed in cities. On special occasions such as weddings and funerals, close and distant relatives gather to help with the preparations. It is common for relatives in rural areas to support those in urban areas with agricultural and dairy products, while people in the cities support their rural relatives with goods from the city and by giving them accommodation when they are in city as well as helping them in matters involving the bureaucracy, health care, and children's education.

Socialization

Infant Care. Infant care differs according to location. In rural areas, infants are placed in cradles or beds. They may be carried by the mother or other female family members. In cities, they usually are placed in small beds and are watched by the mother. Parents interact with babies while attending to their daily chores and prefer to keep babies calm and quiet.

Child Rearing and Education. The criteria for judging a child's behavior are gender-dependent. Although children of all ages are expected to be obedient to their parents and older people in general, boys' misbehavior is more likely to be tolerated. Girls are encouraged to help their mothers, stay calm, and have good manners. It is not unusual for genetic makeup and thus a resemblance to the behavior patterns and talents of their parents and close family members to be used to explain children's negative and positive qualities.

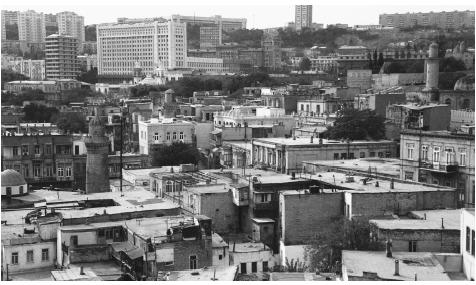

An aerial view of Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan.

Higher Education. Higher education has been important for Azeris both in the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. Having higher education makes both boys and girls more attractive as prospective marriage partners. Parents go to great lengths to pay fees for higher education or other informally determined costs associated with admission to schools.

Etiquette

Issues relating to sex and the body usually are not talked about openly in public. Depending on the age of the speaker, some men may refrain from using words such as "pregnant"; if they must use them, they apologize. It is not considered proper for adults to openly mention going to the bathroom; in private homes, people of the same age and gender or children can be asked for directions to the toilet. Women seldom smoke in public or at parties or other gatherings, and an Azeri woman smoking on the street would be looked down on. To show respect for the elderly, it is important not to smoke in front of older people of both genders. Young men and women are circumspect in the way they behave in front of older people. Bodily contact between the same sexes is usual as a part of interaction while talking or in the form of walking arm in arm. Men usually greet each other by shaking hands and also by hugging if they have not seen each other for a while. Depending on the occasion and the degree of closeness, men and women may greet one another by shaking hands or only with words and a nod of the head. In urban settings, it is not unusual for a man to kiss a woman's hand as a sign of reverence. The awareness of space is greater between the sexes; men and women prefer not to stand close to each other in lines or crowded places. However, all these trends depend on age, education, and family background. Activities such as drinking more than a symbolic amount, smoking, and being in male company are associated more with Russian women than with Azeris. Azeri women would be criticized more harshly, since it is accepted that Russians have different values.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. Among the total population, 93.4 percent is Muslim (70 percent Shia and 30 percent Sunni). Christians (Russian Orthodox and Armenian Apostolics) make up the second largest group. Other groups exist in small numbers, such as Molokans, Baha'is, and Krishnas. Until recently, Islam was predominantly a cultural system with little organized activity. Funerals were the most persistent religious ritual during the socialist era.

Religious Practitioners. In 1980, the sheikhul-Islam (head of the Muslim board) was appointed. Mullahs were not very active during the Soviet period, since the role of religion and mosques was limited. Even today, mosques are most important for the performance of funeral services. Some female practitioners read passages from the Koran in women's company on those occasions.

Rituals and Holy Places. Ramadan, Ramadan Bayram, and Gurban Bayram (the Feast of Sacrifice) are not widely observed, especially in urban areas. Muharram is the period when there are restrictions on celebrations. Ashure is the day when the killing of the first Shia imam, Huseyin, who is regarded as a martyr, is commemorated by men and boys beating their backs with chains while the people watching them, including women, beat their chests with their fists. This ritual was not introduced until the early 1990s, and it attracts an increasing number of people. People go to the mosque to pray and light candles and also visit the tombs of pir (holy men) to make a wish.

Death and the Afterlife. Although people increasingly follow Islamic tradition, owing to the lack of organized religious education, people's beliefs about the afterlife are not clearly defined. The idea of paradise and hell is prominent, and martyrs are believed to go to heaven. After a death, the first and subsequent four Thursdays as well as the third, seventh, and fortieth days and the one year anniversary are commemorated. When there is too little space, a tent is put up in front of people's homes for the guests. Men and women usually sit in separate rooms, food and tea are served, and the Koran is read.

Medicine and Health Care

Western medicine is very widely used, along with herbal remedies, and people visit psychics ( ekstrasenses ) and healers. The sick may be taken to visit pir to help them recover.

Secular Celebrations

The new year's holiday is celebrated on 1 January, 20 January commemorates the victims killed by Soviet troops in Baku in 1990, 8 March is International Women's Day, and 21–22 March is Novruz (the new year), an old Persian holiday celebrated on the day of the vernal equinox. Novruz is the most distinctive Azeri holiday, accompanied by extensive cleaning and cooking in homes. Most households grow semeni (green wheat seedlings), and children jump over small bonfires; celebrations also are held in public spaces. Other holidays are 9 May, Victory Day (inherited from the Soviet period); 28 May, Day of the Republic; 9 October, Armed Forces Day; 18 October, State Sovereignty Day; 12 November, Constitution Day; 17 November, Day of Renaissance; and 31 December, Day of Solidarity of World Azeris.

The Arts and Humanities

Support for the Arts. State funds during the socialist era provided workshops for painters and other artists. Such funds are now limited, but national and international sponsors encourage artistic activity.

Literature. The book of Dede Korkut and the Zoroastrian Avesta (which date back to earlier centuries but were written down in the fifteenth century) as well as the Köroglu dastan are among the oldest examples of oral literature (dastans are recitations of historical events in a highly ornamented language). Works by poets such as Shirvani, Gancavi, Nasimi, Shah Ismail Savafi, and Fuzuli produced between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries are the most important Persian- and Turkish-language writings. The philosopher and playwriter Mirza Fath Ali Akhunzade (Akhundov), the historical novelist Husein Javid, and the satirist M. A. Sabir all produced works in Azeri in the nineteenth century. Major figures in the twentieth century included Elchin, Yusif Samedoglu, and Anar, and some novelists also wrote in Russian.

Graphic Arts. The tradition of painted miniatures was important in the nineteenth century, while the twentieth century was marked by examples of Soviet social realism and Azeri folklore. Among the widely recognized painters, Sattar Bakhulzade worked mainly with landscapes in a manner reminiscent of "Van Gogh in blue." Tahir Salakhov painted in Western and Soviet styles, and Togrul Narimanbekov made use of figures from traditional Azeri folk tales depicted in very rich colors. Rasim Babayev cultivated his own style of "primitivism" with hidden allegories on the Soviet regime (bright saturated colors, an absence of perspective, and numerous nonhuman characters inspired by folktales and legends).

Performance Arts. The local and Western musical tradition is very rich, and there has been a jazz revival in Baku in recent years. Pop music is also popular, having developed under Russian, Western, and Azeri influences. The Soviet system helped popularize a systematic musical education, and people

An Azerbaijani folk dancer performs a traditional dance.

from all sectors of society participate in and perform music of different styles. While composers and performers of and listeners to classical music and jazz are more common in urban places, ashugs (who play saz and sing) and performers of mugam (a traditional vocal and instrumental style) can be found all over the country. It is not unusual to find children who play piano in their village homes. Traditional string, wind, and percussion instruments ( tar , balaban , tutak , saz , kamancha , nagara ) are widely used. Uzeyir Hacibeyov, who is claimed to have written the first opera ( Leyli and Madjnun )in the Islamic East in the early twentieth century, Kara Karayev, and Fikret Amirov are among the best-known classical composers. Both now and in the past, elements from Azeri music have been incorporated into classical and jazz pieces (e.g., the pianist and composer Firangiz Alizade, who recently played with the Kronos Quartet). Beside Western ballet, traditional dances accompanied by accordion, tar , and percussion are popular.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Universities and institutions of higher education from the Soviet era have been joined by new private universities. The Academy of Sciences has traditionally been the site of basic research in many fields. Social sciences were developed within the Soviet framework, although the directions of study are changing slowly with international involvement. Financial difficulties mean that all research is subject to constraints, but oil-related subjects are given a high priority. State funds are limited, and international funds are obtained by institutions and individual scientists.

Bibliography

Altstadt, Audrey L. The Azerbaijani Turks: Power and Identity under Russian Rule , 1992.

Atabaki, Touraj. Azerbaijan: Ethnicity and Autonomy in Iran after the Second World War , 1993.

Azerbaijan: A Country Study, U.S. Library of Congress: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/aztoc.html .

Cornell, Svante. "Undeclared War: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict Reconsidered." Journal of South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies 20 (4):1–23, 1997. http://scf.usc.edu/∼baguirov/azeri/svante_cornell.html

Croissant, Cynthia. Azerbaijan, Oil and Geopolitics , 1998.

Croissant, Michael P. The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict , 1998.

Demirdirek, Hülya. "Dimensions of Identification: Intellectuals in Baku, 1990–1992." Candidata Rerum Politicarum dissertation, University of Oslo, 1993.

Dragadze, Tamara. "The Armenian-Azerbaijani Conflict: Structure and Sentiment." Third World Quarterly 11 (1):55–71, 1989.

——. "Azerbaijanis." In The Nationalist Question in the Soviet Union , edited by Graham Smith, 1990.

——. "Islam in Azerbaijan: The Position of Women." In Muslim Women's Choices , edited by Camilla Fawzi El-Sohl and Judy Marbro, 1994.

Fawcett, Louise L'Estrange. Iran and the Cold War: The Azerbaijan Crisis of 1946 , 1992.

Goltz, Thomas. Azerbaijan Diary: A Rogue Reporter's Adventures in an Oil-Rich, War-Torn Post-Soviet Republic ,1998.

Hunter, Shireen. "Azerbaijan: Search for Identity and New Partners." In Nation and Politics in the Soviet Successor States , edited by Ian Bremmer and Ray Taras, 1993.

Kechichian, J. A., and T. W. Karasik. "The Crisis in Azerbaijan: How Clans Influence the Politics of an Emerging Republic." Middle East Policy 4 (1B2): 57B71, 1995.

Kelly, Robert C., et al., eds. Country Review, Azerbaijan 1998/1999 , 1998.

Nadein-Raevski, V. "The Azerbaijani-Armenian Conflict: Possible Paths towards Resolution." In Ethnicity and Conflict in a Post-Communist World: The Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China , edited by Kumar Rupesinghe et al., 1992.

Robins, P. "Between Sentiment and Self-Interest: Turkey's Policy toward Azerbaijan and the Central Asian States." Middle East Journal 47 (4): 593–610, 1993.

Safizadeh, Fereydoun. "On Dilemmas of Identity in the Post-Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan." Caucasian Regional Studies 3 (1), 1998. http://poli.vub.ac.be/publi/crs/eng/0301–04.htm .

——. "Majority-Minority Relations in the Soviet Republics." In Soviet Nationalities Problems , edited by Ian A. Bremmer and Norman M. Naimark, 1990.

Saroyan, Mark. "The 'Karabakh Syndrome' and Azerbaijani Politics." Problems of Communism , September-October, 1990, pp. 14–29.

Smith, M.G. "Cinema for the 'Soviet East': National Fact and Revolutionary Fiction in Early Azerbaijani Film." Slavic Review 56 (4): 645–678, 1997.

Suny, Ronald G. The Baku Commune, 1917–1918: Class and Nationality in the Russian Revolution , 1972.

——. Transcaucasia: Nationalism and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia , 1983.

——. "What Happened in Soviet Armenia." Middle East Report July-August, 1988, pp. 37–40.

——."'The Revenge' of the Past: Socialism and Ethnic Conflict in Transcaucasia." New Left Review 184: 5– 34, 1990.

——. "Incomplete Revolution: National Movements and the Collapse of the Soviet Empire." New Left Review 189: 111–140, 1991.

——. "State, Civil Society and Ethnic Cultural Consolidation in the USSR—Roots of the National Question." In From Union to Commonwealth: Nationalism and Separatism in the Soviet Republics , edited by Gail W. Lapidus et al., 1992.

——, ed. Transcaucasia, Nationalism, and Social Change: Essays in the History of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia , 1996 (1984).

Swietochowski, Tadeusz. Russian Azerbaijan, 1905B1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community , 1985.

——. "The Politics of a Literary Language and the Rise of National Identity in Russian Azerbaijan before 1920." Ethnic and Racial Studies 14 (1): 55–63, 1991.

——. Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition , 1995.

——, ed. Historical Dictionary of Azerbaijan , 1999.

Tohidi, N. "Soviet in Public, Azeri in Private—Gender, Islam, and Nationality in Soviet and Post-Soviet Azerbaijan." Women's Studies International Forum 19 (1–2): 111–123, 1996.

Van Der Leeuw, Charles. Azerbaijan: A Quest for Identity , 1999.

Vatanabadi, S. "Past, Present, Future, and Postcolonial Discourse in Modern Azerbaijani Literature." World Literature Today 70 (3): 493–497, 1996.

Yamskov, Anatoly. "Inter-Ethnic Conflict in the Trans-Caucasus: A Case Study of Nagorno-Karabakh." In Ethnicity and Conflict in a Post-Communist World: The Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and China , edited by Kumar Rupesinghe et al., 1992.

—H ÜLYA D EMIRDIREK