Culture of Mongolia - history, people, clothing, traditions, women, beliefs, food, customs, family (original) (raw)

- Countries and Their Cultures

- Ma-Ni

- Culture of Mongolia

Culture Name

Mongolian, Mongol

Alternative Names

Formerly called Mongolian People's Republic (1921–1989)

Orientation

Identification. Genghis Khan banded the Mongolian tribes together for the first time in 1206 and formed a unified state. The steppe empires and nomadic culture created by the ancient Mongols hold a unique place in world history, and modern Mongols are very proud of this particular heritage.

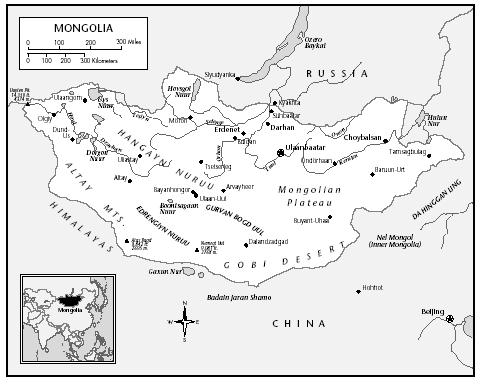

Location and Geography. Mongolia is a large landlocked country in Central Asia, and is bordered on the north by the Russian Federation and on the south by the People's Republic of China. Measuring 604,100 square miles (1,565,000 square kilometers) in area, the country is larger than Western Europe, encompassing several geographical zones: desert, steppe, and mountainous terrain. Mongolia's climate is extreme, with low precipitation and long harsh winters where temperatures can dip to -50 degrees centigrade. The capital city is Ulaanbaatar, meaning "Red Hero."

Demography. With only 2.6 million people as of July 2000, Mongolia is one of the world's most sparsely populated countries. The nation also has an extremely young population, with over 70 percent of people less than thirty years old.

Linguistic Affiliation. Khalkha Mongolian is the official language and is spoken by 90 percent of the people. Minor languages include Kazakh, Russian, and Chinese. Khalka Mongolian is part of the diverse Uralic-Altaic language family, which spread with the ancient Mongol Empire and also contains Korean, Manchu, Turkish, Finnish, and Hungarian. Each of these languages features a highly inflected grammar. Khalkha Mongolian may be written in traditional Uighur (vertical) or Cyrillic script.

Symbolism. The national symbol is the soyombo, featured on the Mongolian flag. Each aspect of the complex design is meaningful and there are components representing fire, sun, moon, earth, water, and the yin-yang symbol. The soyombo dates to at least the 17th century, and is associated with Lamaism.

History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. The name "Mongol" first appears in historical records in the 10th century C.E. Until the late 12th century, the Mongols were a fragmented group of warring clans. In 1162, a Mongol named Temujin was born who eventually became the leader of the Borjigin Mongol clan. After twenty years of warfare, he united most of the Mongol clans and was given the honorary title Genghis Khan ("Universal King") in 1206. The unparalleled conquests of the Mongols under Genghis Khan enabled them to expand their empire far beyond their own territories in Asia, as far as central Europe. The Mongol Empire lasted approximately 175 years, until internal conflicts caused its power to wane. In the 17th century, the former empire lost its independence and was ruled by the Manchus for 200 years. In 1911 the Manchu government was overthrown; the Mongols spent the next ten years freeing themselves from Chinese domination with Russian assistance. A decade of political and military struggles led to the Mongolian-Soviet treaty of 1921, which recognized Mongolia's independence. In 1924, the Mongolian People's Republic was officially established as the second socialist nation in the world after the U.S.S.R. Major democratizing political and economic reforms began in the late 1980s following the disintegration of the U.S.S.R. This democratic movement resulted in the emergence of

Mongolia

multiple political parties and the beginnings of a free market economy by 1990.

National Identity. National culture—including societal organization, governance, land management, cultural customs, and material culture—was largely shaped by the nomadic pastoral lifestyle. The legacy of Genghis Khan's empire is a rallying point for Mongol nationalist pride today.

Ethnic Relations. Approximately 78 percent of people are Khalkha Mongols. Minority groups include Kazakh, Dorvod, Bayad, Buriad, Dariganga, Zahchin, Urianhai, Oolld. and Torguud. The largest of these minority groups, Kazakhs make up 4 percent of the total population. Small numbers of Russians and Chinese permanently live in Mongolia. While relations between Mongols and Russians are generally warm, widespread resentment exists among Mongols for the growing presence of entrepreneurial Chinese in their country.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

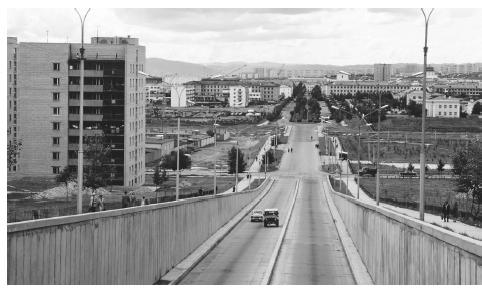

Rapid urbanization and industrialization accompanied extensive Soviet aid following World War II and in the 1950s, the country adopted a new economic strategy that added industrial activities and more extensive farming to its mainstay of livestock production. Many people migrated from rural to urban areas to work in the new industrial centers, and a population that was 78 percent rural in 1956 was 58 percent urban by 1990. Many urban settlers continued to live in traditional nomadic gers, round tents made of folding wooden walls and heavy felt outer coverings.

Food and Economy

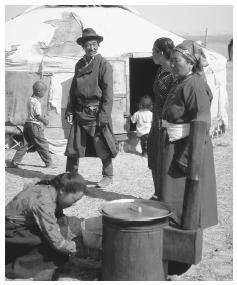

Food in Daily Life. Approximately twenty five million head of livestock supply the staples of the diet; meat and dairy products feature prominently in this cuisine. Mongolian cooking is generally very simple and does not use many spices, flavorings or sauces. Common dishes include steamed meat–filled dumplings ( buuz ), mutton soup with noodles ( guriltai shul ) and fried meat pasties ( huushuur ). Mongolians drink copious quantities of milk tea ( suutei tsai ), which frequently contains salt and a generous spoonful of fresh or rancid butter.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. Food is an important element of the Mongolian hospitality tradition. When guests arrive, each household sets out a special hospitality bowl containing homemade cheeses, flour pastries ( bordzig ), sugar cubes and candy. The fattest animals are slaughtered to be eaten. Meat-filled dumplings are traditionally served to guests. Vodka shots are served at regular intervals during a celebration.

Basic Economy. Primary to the economy are the "five types of animals:" sheep, goats, cattle (mainly yak), horses, and camels. From these livestock numerous animal products are harvested, including meat, dairy products, hides, and wool. Agricultural production takes place in some regions where grains (wheat, barley, oats), animal fodder, potatoes, and other vegetables are grown. The country is rich in natural resources including coal, copper, gold, fluorspar, and molybdenum, and has prospective areas for oil extraction that are currently being explored.

The national currency is the tugrik.

Land Tenure and Property. Before socialism, a quasi-feudal system existed in which local aristocratic families and monasteries primarily governed: they administered pastureland, settled disputes between herding households, and collected taxes. Herders mostly owned their animals but paid taxes to the nobility for using pastureland. In the 1920's, the U.S.S.R. forced rural collectivization of herds within the Soviet Union and encouraged the Mongolian government to follow suit. However, widespread resistance by herders delayed the implementation of nationwide herding collectives until after World War II. Under the socialist system, the numbers of private animals that could be owned was tightly restricted, but these restrictions began to be lifted in the late 1980's.

Major Industries. A number of manufacturing plants were built under socialism which continue to operate today. Industries include food and beverage processing, leather goods, textiles, carpets, chemicals, cement, and mining operations, especially coal mining.

Trade. Under socialism, the country participated in Comecon, the U.S.S.R.-led, Communist-bloc trade organization. Approximately 85 percent of foreign trade was with the Soviet Union. In the early 1990's, the abrupt loss of foreign aid from the U.S.S.R. along with new trade policies among the former Soviet satellite nations resulted in major economic disruption. Since then, the country has been developing its free market economy and products now being exported include livestock, animal products, cashmere, wool, hides, copper, and fluorspar and other nonferrous metals. The country maintains trade relations with over 25 countries and joined the World Trade Organization in 1997.

Division of Labor. In rural areas of the country, livestock production still predominates followed by crop production. In herding households, people of all ages are involved in safeguarding, caring for, and increasing the herds on which they subsist. While both young men and women participate in herding activities, older persons may help with caring for animals at the campsite and doing household chores including repairing tools, preparing hides, sewing, cooking, and childcare. By contrast, in urban areas manufacturing, industrial, and service-oriented jobs are the norm. For these jobs, specialized abilities and training are more frequently required.

Social Stratification

Classes and Castes. Like many nomadic pastoral cultures, the Mongols had a segmentary society, originally organized into a hierarchy of families, clans, tribes, and confederations. While social classes including nobility, herders, artisans, and slaves existed, the social structure was not completely rigid and social mobility was possible. Under socialism, economic and social equality increased as variation in herd size and wealth levels was reduced. Economic expansion and rapid industrialization also contributed to increasing social mobility. The post-socialist period has been marked by increasing wealth differentiation. While certain segments of the population, such as new entrepreneurs, have prospered in the 1990s, others have become rapidly impoverished.

Symbols of Social Stratification. In ancient times, material cultural objects including headdresses, clothing, horse-blankets and saddles, jewelry, and other personal objects were visual symbols of tribal affiliation and social status. Today emerging wealth is often shown by purchasing and displaying

Two cars travel up a street in the capital city of Ulan Bator. The population in 1990 was 58 percent urban.

expensive imported goods from Western countries.

Political Life

Government. As a socialist nation, Mongolia modeled its political and economic systems on those of the U.S.S.R. For seven decades, the Mongolian People's Revolutionary Party (MPRP) governed, working closely with the Soviet Union. A major transition in governmental structure and political institutions began in the late 1980s in response to the collapse of the U.S.S.R. Free elections in 1990 resulted in a multiparty government that was still mostly Communist. A new constitution was adopted in 1992. In 1996, the Communist MPRP was defeated for the first time since 1921 by an electoral coalition called the Democratic Alliance. However, after four turbulent years and a series of prime ministers, the MPRP regained control of the government in 2000.

The highest legislative body is a unicameral parliament called the State Great Hural with 76 elected members. A president serves as the head of state and a prime minister is the head of government. After legislative elections, the leader of the majority party is typically elected prime minister by the parliament. The president is elected to a four year term by popular vote. Local government leaders are elected at the aimag (provincial) and soum (district) levels.

Social Problems and Control. The original Mongolian legal code was the yasa , a body of laws created after Genghis Khan's death but greatly influenced by his system of state administration. This legal code dealt with military discipline, criminal law and societal customs and regulation. The modern legal system is closely related to that of the Soviet Union. Under socialism, crimes committed against the state and/or socialist owned property were treated particularly harshly. In the post socialist era, emerging poverty has resulted in an increase in crimes such as property theft and robbery, especially in the major cities.

Military Activity. Situated in the geographically strategic location between Russia and China, the country is deeply concerned with national security issues. Mongolian and Soviet troops have generally been closely allied throughout the 20th century. These armies fought together in the 1921 Mongolian Revolution and in the 1930s against Japanese border incursions. Under socialism, both Soviet and Mongolian military bases existed in the Gobi region where the Mongolian border with China was heavily guarded.

Mongolian nomads cook at a stove outside a yurt. Meat and dairy products are a predominant staple of the diet.

Social Welfare and Change Programs

An elaborate social welfare system was established under socialism, providing all citizens with access to health care, education, and pensions. The government received significant subsidies from the U.S.S.R. to pay for these generous programs. Following the withdrawal of Soviet aid, funding these programs has been a major challenge. New social problems, such as the existence of several thousand street children, have arisen as fallout from the ongoing economic crisis.

Gender Roles and Statuses

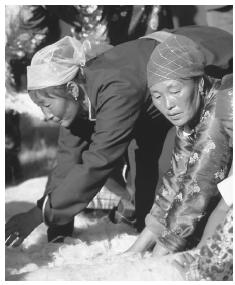

Division of Labor by Gender. For many centuries, there was a customary gender division of labor in this nomadic pastoral society. Men typically handled external affairs including military, administrative, and trade matters. Men were primarily responsible for herding animals, hunting, slaughtering animals, and maintaining animal shelters. Repairing carts, tools, and weapons were also considered men's work. Women were mainly responsible for housework, milking animals, making dairy products, cooking, washing, sewing, and nurturing children.

Relative Status of Women and Men. Unlike their counterparts elsewhere in Asia, Mongolian women historically enjoyed fairly high status and freedom. Since fertility was valued over virginity, the Mongols did not place the same emphasis on female purity as found in the Islamic societies in Asia. Although women had legal equality with men under socialism, they were burdened with the responsibilities of housework and childcare as well as their labor for wages.

Marriage, Family, and Kinship

Marriage. Traditionally, families were the main unit of production in this herding society. The kinship system was patrilineal and sons generally established households in a common camp with their fathers. Marriages were arranged by parents and a bridal dowry (usually consisting of animals) was negotiated based upon the social status of the families. The 20th-century norm became for children to choose their own marriage partners with less extensive parental involvement.

Domestic Unit. Several generations of families customarily live together in a nomadic camp known as a khot ail ("group of tents") and share herding tasks. This camp, generally consisting of two to seven households, serves as a way of pooling labor for herding and has numerous social and ritual functions. Besides the khot ail, a larger neighborhood group called neg nutgiinhan ("people of one place") generally consists of four to twenty khot ails that frequently move and work together.

Inheritance. Historically, the cultural pattern of old age support was ultimogeniture and the youngest son would typically inherit the largest share of the parent's animals. Today, there is greater variation in inheritance depending on personality considerations and the economic and living circumstances of different family members.

Socialization

Child Rearing and Education. Children have always been treasured in Mongolian culture, and large families were historically the norm. Large families were considered desirable because many children ensured extra help and security in old age. Although family size is changing today, the country is still so sparsely populated that some people still believe it is advantageous to have "as many Mongolians as possible." Attitudes about child rearing are generally quite relaxed and all family members participate in the supervision and moral education of children. Under socialism, a high value was placed on elementary education and literacy. While education was limited to monks in Buddhist monasteries before the 20th century, under socialism the adult literacy rate rose to over 90 percent.

Higher Education. The Mongolian State University was founded in 1942. Much of the teaching was originally in Russian due to a lack of Mongol language texts in specialized fields. Under socialism, the higher education system provided opportunities for promising students from all regions of the country to participate in advanced study in the Soviet Union or in Eastern Europe and education was closely linked to upward social mobility.

Etiquette

Hospitality has always been extremely important in Mongolian culture. Since visitors often travel great distances, there are many ritual ways of showing politeness, especially to guests. One such custom that remains from feudal times is the snuff bottle ritual— a guest and host offer each other their snuff bottles to examine as part of a greeting ritual. It is customarily expected that guests will be served the finest food possible and that vodka will also be plentiful.

Religion

Religious Beliefs. The main religion is Lamaism, which is the Yellow Sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Until the 16th century, shamanism was the dominant religion in Mongolia. Lamaism was introduced to the populace by the leader Altan Khan (1507–83). In the 18th century, the Manchus further encouraged Lamaism since they preferred Mongol males to become monks rather than warriors. Paralleling the Stalinist period in the Soviet Union, communists held massive religious purges in the 1930s. More than 700 monasteries were destroyed and thousands of monks were killed. In the post-socialist period, Buddhism is experiencing a resurgence and young people are again learning Buddhist practices from their elders who still remember them from their own childhoods. Approximately 5 percent of the total Mongolian population are Sunni Muslims, mainly ethnic Kazakhs in the western region. After 1990, Western missionaries arrived in Mongolia and began to proselytize; there may be as many as several thousand Mongolian Christians today.

Religious Practitioners. As the importance of Lamaist temples grew in the society, each Mongol

Women making felt in Undursant. Traditionally, women enjoyed high social status.

family was encouraged to provide one son to be raised in a temple and become a lama. Fewer women became nuns although there were some who pursued this career. Training for lamas focused on theological studies and learning to perform elaborate ceremonies to be carried out for the people. Since many temples had extensive libraries, some lamas were also trained in subjects including astronomy, astrology, mathematics, and medicine. While a small percentage of temples were preserved intact under socialism, the majority were dismantled and the lamas returned to the work force at large. In the post-socialist era, those who are familiar with Lamaist traditions are now in great demand to educate younger people who have received no formal religious training.

Rituals and Holy Places. For centuries, Lamaist temples played a central role in community life and were a major gathering place for nomads living considerable distances apart. Although many temples were destroyed under socialism, a number remained standing including three major temples that were preserved as showcases of traditional culture: Gandan Monastery (Ulaanbaatar), Erdene Zuu Monastery (Ovorkhangai), and Amarbayasgalant Monastery (near Darkhan).

Death and the Afterlife. Funerals were traditionally an important and costly event for Mongolian families. They would customarily give lamas substantial monetary gifts to pray for the well-being of the spirit of the deceased. Receiving the lamas' consultation about the handling and disposition of the body was considered very important to prevent future misfortune from occurring to the family. Others in the community would typically provide gifts of animals and money to assist the family at the time of the funeral.

Medicine and Health Care

While basic healthcare became available nationwide under socialism, specialized care remained concentrated in cities. Along with Western-style medicine, herbal medicine, acupuncture, and massage are widely practiced in Mongolia. Based on the Soviet and Eastern European tradition, therapeutic spas became very popular. Although the primary healthcare system operated quite efficiently under socialism, providing adequate healthcare resources in the post-socialist era has proved challenging due to the ongoing economic crisis. Thus, the long-term impact of this major societal transition on health indicators is unknown. In 2000, the estimated life expectancy at birth for the total population was 67.25 years, with male life expectancy being 64.98 years and female life expectancy being 69.64 years.

Secular Celebrations

Major public holidays are New Year's Day (1 January); Lunar New Year or Tsagaan Car, meaning "White Month," a three-day holiday with variable dates in late January to early February); Women's Day (8 March); Naadam, anniversary of 1921 Mongolian Revolution (11–13 July); and Mongolian Republic Day (26 November).

The Arts and Humanities

Literature. Since the Mongols were always highly mobile, most art forms that became popular were portable and involved little or no equipment, such as epic poetry, literature, music, and dance. The most famous epic poem of all time is "The Secret History of the Mongols," a long poem describing Genghis Khan's rise to power and the creation of the Mongol Empire. This poem was written down in the mid- to late-13th century and was supposed to be hidden from non-Mongols. Folktales also played a major role in oral literature and their subject matter ranged from love to heroism to supernatural acts. Modern literature has been heavily influenced by Western literary styles, especially Russian literature.

Graphic Arts. The nature and types of graphic arts found in Mongolia were also influenced by the nomadic heritage. Articles of daily use including saddles, horse blankets, storage chests, and knives were often highly decorative. Painting and sculpture could be found in permanent buildings, such as temples, throughout the country. Religious themes dominated traditional painting and sculpture because these art forms were largely produced within Lamaist temples. The Museum of Fine Arts in Ulaanbaatar has an extensive collection of Lamaistic paintings, sculpture, and other religious objects from different periods. Scroll paintings called tanka that depicted the various gods and saints of Lamaist Buddhism decorated every temple. These paintings were both imported from Tibet and created locally by lamas. Tanka came in a variety of sizes and were often painted on cotton or silk. In the post-socialist period, it has become increasingly popular for Mongol families to own tanka and display them in their homes. Under socialism, local artists produced their own substantial body of Soviet-encouraged socialist art, which is less in favor today.

Performance Arts. Performing arts have been widely practiced in Mongolia for centuries. Today there are many professional and amateur theaters and musical organizations both in the capital and in other provincial towns. In both the socialist and post-socialist eras, the government has been supportive of performing arts and has subsidized traveling shows of operas, plays, ballets, folk music and dancing, and circuses. The most important folk instrument is the morin khuur (horse-head fiddle), a stringed instrument whose name comes from the horse head carved above the tuning pegs. The morin khuur has a trapezoid-shaped body, leather sounding board, and two strings that are played with a bow made of wood and horsehair. Playing from a seated position, the musician rests the morin khuur on his knee. In many areas of the country, men were traditionally expected to know how to play the morin khuur. It is often played together with the tovshuur and the shudraga (two banjo-like stringed instruments). Other instruments used in folk music include transverse and vertical flutes, drums, cymbals, gongs, and tambourines. Like poetry, vocal music is very important in this culture and there are multiple types of folk songs. Herding songs and work songs are most typical and these songs can have specific purposes (e.g., a herding song to call back animals that have strayed or a work song sung while setting up camp). Other types of folk songs include yurol (songs of blessing), maatgal (songs of praise), urtyn duu ("long songs" performed by professional singers with operatic training), and khoomei (harmonic singing in which one performer combines humming and whistling to sound like several people singing at once). In the post-socialist era, the country's youth have embraced Western music and there are quite a few nightclubs in the major cities where one can dance to the same pop music topping the charts in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere in Asia. A growing number of local rock groups are now performing whose music is mainly sold in Mongolia but can also sometimes be found in other Asian countries.

The State of the Physical and Social Sciences

Based on the Soviet model, under socialism the country established specialized research institutes that were separate from the academic departments which taught science in universities. The Mongolian Academy of Science was founded in 1961 and had at least 14 working research institutes by the 1980s. In the post-socialist period, the Mongolian Academy of Science fell upon hard times during the national economic crisis. However, funding from a variety of international organizations enabled some Mongolian scientists to study abroad and have access to state-of-the-art equipment. The Academy also has Internet access, allowing scientists to easily communicate with their scholarly peers in other nations.

Bibliography

Bawden, C. R. The Modern History of Mongolia, 1989.

Bruun, O. and O. Odgaard, eds. Mongolia in Transition: Old Patterns, New Challenges, 1996.

Cooper, L. Patterns of Mutual Assistance in the Mongolian Pastoral Economy, 1994.

——. Wealth and Poverty in Pastoral Economy, 1995.

De Hartog, L. Genghis Khan: Conqueror of the World 1989.

Dondog, L., ed. Mongolia Foreign Investment Trade and Tourism, 1996.

Goldstein, M., and C. Beall. The Changing World of Mongolia's Nomads, 1994.

Griffin, K., ed. Poverty and the Transition to a Market Economy in Mongolia, 1995.

Harper, C. An Assessment of Vulnerable Groups in Mongolia, 1992.

Jagchid, S., and P. Hyer. Mongolia's Culture and Society, 1979.

Major, J. S. D. The Land and People of Mongolia, 1990.

Mearns, R. Pastoral Institutions, Land Tenure and Land Policy Reform in Post-Socialist Mongolia, 1993.

Morgan, D. The Mongols, 1986.

Neupert, R. F. Population Policies, Socioeconomic Development and Population Dynamics in Mongolia, 1996.

Oyunchimeg, D. Mongolian Economy and Society in 1995, 1996.

Potkanski, T. Decollectivisation of the Mongol Pastoral Economy (1991–92): Some Economic and Social Consequences, 1994.

Rossabi, M. China and Inner Asia: From 1368 to the Present Day, 1975.

——. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, 1988.

Rupen, R. How Mongolia Is Really Ruled: A Political History of the Mongolian People's Republic 1900–1978, 1979.

Sneath, D. Social Relations, Networks and Social Organisation in Post-Socialist Rural Mongolia, 1994.

Storey, R. Mongolia, 1993.

Swift, J. Rural Development: The Livestock Sector in Poverty and the Transition to a Market Economy in Mongolia, 1995.

Templer, G., J. Swift, and P. Payne. The Changing Significance of Risk in the Mongolian Pastoral Economy, 1994.

World Bank. Mongolia Poverty Assessment in a Transition Economy, 1996.

World Factbook. Mongolia, 1999.

Web Sites

Permanent Mission of Mongolia to the United Nations. www.undp.org/missions/mongolia/mngstate.htm , 2000.

—S HERYLYN H. B RILLER

M ONTENEGRO S EE S ERBIA AND M ONTENEGRO

Also read article about Mongolia from Wikipedia