City and Book, Florence, 2001, Part 2 (original) (raw)

****FLORIN WEBSITE A WEBSITE ON FLORENCE � JULIA BOLTON HOLLOWAY, AUREO ANELLO ASSOCIAZIONE, 1997-2022: ACADEMIA BESSARION || MEDIEVAL: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, SWEET NEW STYLE: BRUNETTO LATINO, DANTE ALIGHIERI, & GEOFFREY CHAUCER || VICTORIAN : WHITE SILENCE: FLORENCE'S 'ENGLISH' CEMETERY || ELIZABETH BARRETT BROWNING || WALTER SAVAGE LANDOR || FRANCES TROLLOPE || ABOLITION OF SLAVERY || FLORENCE IN SEPIA || CITY AND BOOK CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS I, II, III,IV,V,VI,VII** , VIII, IX, X || MEDIATHECA 'FIORETTA MAZZEI' || EDITRICEAUREO ANELLO CATALOGUE || UMILTA WEBSITE || LINGUE/LANGUAGES: ITALIANO,ENGLISH || VITA New: Opere Brunetto Latino || Dante vivo || White Silence

LA CITTA` E IL LIBRO I

EVENTI INTERNAZIONALI

ALLA CERTOSA DI FIRENZE

30, 31 MAGGIO, 1 GIUGNO 2001

THE CITY AND THE BOOK I

INTERNATIONAL CONGRESSES

IN FLORENCE'S CERTOSA

30, 31 MAY, 1 JUNE 2001

ATTI/ PROCEEDINGS

SECTION II: LA BIBBIA CRISTIANA

THE CHRISTIAN BIBLE

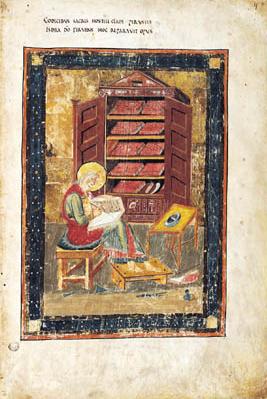

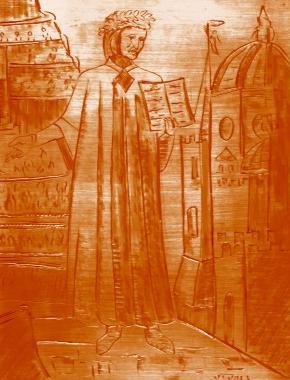

Incisione, Bruno Vivoli

Repubblica di San Procolo, 2001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

SECTION II: THE CHRISTIAN BIBLE: The CODEX SINAITICUS and the CODEX ALEXANDRINUS: A Tale of Four Cities , Dr Scot McKendrick, British Library (unavailable, non disponibile) || Jerome and His Learned Lady Disciples , dott. Claudio Moreschini, Universit� di Pisa (italiano, English) ||Bishop Wulfila and the CODEX ARGENTEUS , Dr James Marchand, University of Illinois (English, italiano) || Cassiodorus , dott.ssa Luciana Cuppo Csaki, Societas internationalis pro Vivario (italiano, English) ||

Map and Time Line

Book Fair

Florin

Pranzo, Certosa del Galluzzo

13,00/ 1:00 p.m.

Certosa del Galluzzo 14,00-17,00/ 2:00-5:00 p.m.

LA BIBBIA CRISTIANA/

THE CHRISTIAN BIBLE

Presiede/Chair, professore Claudio Leonardi, S.I.S.M.E.L.;

Professor Martin McNamara, Woodview, Dublin, Ireland.

CODEX SINAITICUS, CODEX ALEXANDRINUS, AND THE EARLY CHRISTIAN BIBLE: A TALE OF FOUR CITIES/

CODEX SINAITICUS, CODEX ALEXANDRINUS E LA BIBBIA CRISTIANA ANTICA: UN CONTO DI QUATTRO CITTA'

DR SCOT MCENDRICK, CURATOR OF CLASSICAL, BYZANTINE AND BIBLICAL MANUSCRIPTS, BRITISH LIBRARY, LONDON, ENGLAND [UNAVAILABLE]

CULTURA CRISTIANA A ROMA: GIROLAMO E LE SUE DOTTE DISCEPOLE/

CHRISTIAN CULTURE IN ROME: JEROME AND HIS LEARNED LADY DISCIPLES

PROF. CLAUDIO MORESCHINI, UNIVERSITA' DI PISA

{ Nel 381 Girolamo arriva a Roma, proveniente da Costantinopoli, ricco di esperienze, come quella della vita eremitica nel deserto, quella delle discussioni teologiche e della conoscenza di Gregorio Nazianzeno, il vescovo di Costantinopoli, della composizione di alcune opere erudite, della conoscenza del greco e dell�ebraico, cosa, quest�ultima, assai rara nella cristianit� antica.

In 381 Jerome arrived in Rome, from Constantinople, full of the experiences of his life as a hermit in the desert, and his theological arguments and friendship with Gregory Nazianzene, the bishop of Constantinople, his writings, including a number of profoundly learned works, his knowledge of Greek and Hebrew which was, especially the latter, extremely rare among the early Christians.

A Roma � forte la presenza del papa Damaso, che lo incoraggia. Damaso � sul soglio di Pietro gi� da quindici anni, e gode di un forte potere politico e di una indiscussa autorit�. L�imperatore non � pi� a Roma, ma, insieme con la sua corte, � a Milano. Damaso incoraggia Girolamo a iniziare la grande, ventennale fatica della revisione del testo biblico, che � comunemente chiamata la Vulgata.

In Rome, the power of Pope Damasus was strong, and he encouraged Jerome. Damasus had been on the throne of Peter for fifteen years by then, and his political power was firm and unquestioned. The emperor no longer had his court in Rome, but had transferred it to Milan. Damasus invited Jerome to undertake the great, twenty-year task of revising the text of the Bible that is commonly known as the Vulgate.

L�insegnamento di Girolamo trova risonanza nell'ambiente dell�aristocrazia romana e dei senatori, ma, cosa significativa, non nei patresfamilias di essa, i quali sono, per tradizione e per necessit� politica, ancora tutti pagani. Accanto a questo cieco tradizionalismo si osserva come l�ambiente pagano di Roma, verso la fine del IV sec., sembra segnato da una specie di torpore incurabile. Eccettuati pochi, ancora appassionati dall'amore delle belle lettere, la maggioranza degli uomini ricchi di quel tempo avevano poca o nessuna attrattiva per lo studio. " La biblioteca di un patrizio, scrive non senza una punta di esagerazione uno storico dell'epoca, Ammiano Marcellino , era chiusa ermeticamente e rispettata come una tomba ". Le donne, invece, si mostravano avide di imparare. Erano prese da grande zelo per i lavori intellettuali. Si sarebbe detto che la loro curiosit� si svegliava nel momento stesso in cui ritrovavano " nella vita cristiana, cos� come la vivevano i monaci, la dignit� del sacrificio e l'emancipazione dell'anima", beni che esse apprezzavano tanto di pi�, perch� la civilt� greco-romana le aveva in parte private di quella dignit� e di quella emancipazione si pu� dire da sempre.

The teachings of Jerome met with great interest in the environment of the Roman aristocracy and senate but, significantly, not among the men who, traditionally and for reasons of political convenience were all still pagan. Alongside this blind traditionalism we observe how the pagan environment of Rome, towards the end of the 4th century, seemed to be locked in a sort of incurable torpor. Except for a very few, who were still imbued with passion for great literature, the majority of the rich men of that time had little or no interest in culture. " The library of a patrician, wrote a historian of the period , Ammiano Marcellino, exaggerating just a little, was hermetically sealed and respected much like a tomb". The women, however, were avid to learn. They were gripped by great zeal for intellectual works. It was as though their curiosity was awakened as soon as they discovered "in the Christian life, lived as the monks lived it, the dignity of sacrifice and the emancipation of the soul", values that they appreciated all the more, because the Greek and Roman civilizations had to some extent deprived them of that dignity and emancipation practically from the outset.

Alcuni personaggi dell�ambiente romano, frequentato da Girolamo, e da lui educato ed istruito nel cristianesimo e nella spiritualit�.

Some of the personalities in Roman society who frequented Jerome and were educated and instructed in Christian culture and spirituality.

Tra le donne della aristocrazia romana spicca la figura di Marcella. Costei era particolarmente attratta dall�ascetismo. Quando Girolamo era ancora studente, ella aveva gi� abbandonato simbolicamente il mondo. La sua rinuncia era particolarmente significativa, perch� Marcella apparteneva a una illustre e antica famiglia di Roma. Non aveva goduto a lungo del matrimonio: solo sette mesi. Poi, richiesta in moglie per una seconda volta dal console Cerealis, aveva rifiutato di passare a seconde nozze. Marcella preferiva vivere nella continenza e dedicare le risorse della sua brillante intelligenza per conoscere meglio i libri santi. Questa accentuata attrattiva a scrutare la parola di Dio le rendeva facili tutte le rinunce. Per approfondire il suo studio ella affrontava ogni fatica. Infatti, come riuscire a leggere con calma, quando sentiva gravare su di s� il peso e la preoccupazione di una numerosa servit� e il governo di una casa importante?

Among the women of Roman aristocracy the figure of Marcella stands out. She was particularly attracted by asceticism. When Jerome was still a student she had symbolically withdrawn from the world. Her sacrifice was particularly significant in view of the fact that Marcella was a member of one of the most illustrious ancient families of Rome. She was married only for seven month before being widowed. Then, when the Roman consul Cerealis asked for her hand, she refused this second marriage, preferring to live a celibate life and devote the resources of her brilliant intelligence to the study of the sacred writings. This strong desire to understand the word of God made it easy for her to relinquish worldly things. She had to work very hard to find time for her studies, for it is not easy to read when we have to support the weight of a large staff of servants and the management of an important household.

Viveva ancora sua madre Albina, vedova anch'ella. Essa non ostacolava i nuovi progetti della figlia, anzi, li assecondava, ma ancora molto imperfettamente, perch� coltivava una certa speranza che Marcella, con un secondo matrimonio, potesse rendere un po' di vita alla sua casa ormai cos� triste. La venerabile matrona avrebbe accettato con difficolt�, almeno in quel tempo, di vedere trasformato in monastero il suo magnifico palazzo. Nonostante queste difficolt�, Marcella continuava ad accarezzare i suoi progetti di studi religiosi e il suo sogno di vita monastica. Era gi� passata alle prime realizzazioni. Aveva venduto tutti i suoi gioielli e persino l'anello che le serviva da sigillo per la corrispondenza. Vestiva in modo molto semplice, per necessit� pi� che per civetteria, ma questa rinuncia non le costava affatto; l'interessava solo la scienza sacra. Impiegava, a studiare la Scrittura, tutto il tempo di cui disponeva. Meno favorita dalla sorte della sua compagna Asella che, libera da qualsiasi impegno, poteva rinchiudersi nella sua cameretta a meditare con tranquillit� la legge di Dio, Marcella sopportava con serenit� la sua condizione. Cercava di procurarsi quanto pi� tempo poteva, sottraendolo ai doveri mondani o alle visite che le sarebbe piaciuto fare alle tombe dei martiri, per restare insieme al testo sacro. Manifestava ad alta voce i suoi interessi, cantando sempre questi versetti del salmo: "Ho nascosto nel mio cuore le tue parole per non peccare..." (Sal 118, 11). " Il piacere del giusto � nella Legge di Dio. Egli la medita giorno e notte" (Sal 1, 2). Come Girolamo all'indomani della sua conversione, cos� anche Marcella trovava nella lettura sacra una regola di vita e una gioia per il cuore. Come Girolamo, anche Marcella aveva bisogno di soddisfare vere esigenze dello spirito. Il senso letterale del testo sacro le interessava non meno di quello mistico. Nonostante la mancanza di studi approfonditi, era capace di avanzare senza sforzo in questa ricerca fredda e severa, che anzi offre una visione netta della verit�, senza deformarla. Era in grado di offrire quel lavoro di astrazione che � proprio delle menti pi� razionali. Era un'intellettuale nel senso ampio e profondo della parola. Curiosa e inquieta, difficilmente si accontentava delle prime risposte. Inseguiva con tenacia i suoi interrogativi, non tanto per bisogno di contestare, quanto per il piacere di prolungare in qualche modo i dibattiti e di ravvivarli, riservandosi sempre di ridiscutere le risposte ottenute. In una parola, era giudice e nello stesso tempo discepola.

Her mother, Albina, also a widow, was still alive. She did not hinder her daughter and, indeed, applauded her interests, but not without some misgivings, because she still had hopes that Marcella, with a second marriage, could restore a little life to a house that had become far too sanctimonious in her opinion. The venerable matron would have found it hard to accept, at least then, that her magnificent palace should become a monastery. In spite of these problems, Marcella continued her studies and pursued her dream of a monastic life. She had already taken the first steps. She had sold all her jewels and even the ring with the seal she used for her correspondence. She dressed very simply, out of need more than vanity, but this was no sacrifice for her; she was interested only in sacred science. She spent all her free time studying the Scriptures. She was less favored by destiny than her companion Asella who, having no responsibilities at all, could shut herself up in her room and meditate at leisure on the law of God, but Marcella supported her condition serenely. She tried to save herself as much time as she could, avoiding social occasions or even visits she would have liked to make to the tombs of the martyrs, to stay at home with her sacred texts. She expressed her interests vocally, always repeating these verses from the Psalms: "I have hidden thy words in my heart so as not to sin..." (Sal 118, 11). "The pleasure of rightness is in the Law of God. He meditates on it day and night" (Sal 1, 2). Like Jerome on his conversion, Marcella too found in the sacred readings a rule for living and a joy for the heart. Like Jerome, Marcella too needed to satisfy the real needs of the spirit. The literal sense of the sacred text interested her no less that its mystical significance. In spite of her lack of serious education, she was able to progress without difficulty in this austere, demanding research that, indeed, offered her a clear view of the truth, without distorting it. She was able to apply herself to the work of abstraction that is one of the properties of the most rational minds. She was an intellectual in the broadest and deepest sense of the word. Curious and restless, she was seldom satisfied with the first answers. She tenaciously pursued her questing, not so much from a desire to challenge others as from a pleasure in prolonging discussion any way she could, and stimulate them, always reserving the right to question the responses given. In a word, she was judge and disciple at the same time.

La sua cultura raffinata e vasta, quella che veniva impartita alle fanciulle patrizie di allora, non la disponeva ad adattarsi alla povert� delle traduzioni latine della Bibbia, cos� come era accaduto per lo stesso Girolamo. D'altra parte, la lettura sacra faceva sorgere nella sua mente curiosa molte difficolt�, che non riusciva sempre a chiarire. Capiva che la soluzione le poteva venire solo da uno specialista, che conoscesse le lingue sacre. Cos�, l'arrivo di Girolamo a Roma la ricolm� di gioia. Ma come accostarlo? La cosa non era facile. Il soggiorno nel deserto aveva reso Girolamo diffidente verso le donne. C'era solo un mezzo per farlo uscire da questa riservatezza un po' ombrosa: invitarlo discutere su questioni relative alle Scritture. � su questa base che Marcella avvi� le prime relazioni. Lo sommerse di quesiti. E Girolamo si rese conto ben presto con chi aveva a che fare. A poco a poco le conversazioni divennero vere sedute di esegesi e riprendevano ogni volta che si incontravano, anche quando Marcella aveva molta fretta. Quando ebbero inizio questi incontri, Marcella aveva molti quesiti arretrati da risolvere. Marcella allora, come si � detto, non era pi� giovane. Era una rispettabile vedova, di almeno cinquant'anni e quindi aveva una mente matura, con, alle sue spalle, una lunga esperienza di letture e di vita monastica. Girolamo era vicino alla quarantina. Aveva il privilegio di superare Marcella nella scienza. Arrivava direttamente dall'oriente, portando con se "mercanzie" rare e misteriose che incuriosivano molto tutti, in particolare Marcella. Girolamo che cercava discepoli, ora aveva una allieva molto ben disposta ad approfittare delle sue lezioni, e cos� si sentiva ripieno di ammirazione per colei che doveva diventare, secondo il superlativo affettuoso con cui si compiacque di chiamarla spesso in seguito, la grande studiosa, colei che l'avrebbe stimolato al lavoro. Marcella cos� assecondava molto felicemente Girolamo nel suo apostolato intellettuale, con cui questi cercava di conquistare candidati alla vita perfetta e alla scienza sacra. Ma � chiaro che tali conquiste si fanno sia con il contatto diretto delle persone sia con gli scritti. Ora Marcella possedeva, meglio di Girolamo, cos� impulsivo ed iracondo, una sensibilit� equilibrata, unita a una squisita amabilit�, cui � difficile resistere. Sapeva placare l'ardore battagliero del suo irascibile maestro, che troppo facilmente si arrogava il titolo di � chirurgo spirituale �. Avvalendosi di questo titolo, egli affondava il ferro, senza troppe precauzioni, nelle piaghe morali dei suoi concittadini. L'interesse che Marcella aveva per Girolamo era tale che, se autorizzata, non avrebbe esitato a chiudere con la sua mano quella bocca dalla quale, nei momenti di eccessiva franchezza, sfuggivano spesso parole troppo imprudenti. Ad ogni modo, non mancava di segnalare la sua disapprovazione con lo sguardo o con il gesto. Quando la fronte di Marcella si corrugava, Girolamo stava in guardia, temendo qualche rimbrotto. Quante volte, senza l'intervento della sua giudiziosa allieva, la sua libert� di linguaggio e di penna gli avrebbero causato le peggiori avventure!

Her vast, refined culture, as taught to the patrician girls of the time, had not prepared her to deal with the poor quality of the Latin translations of the Bible, just as had occurred to Jerome. On the other hand, her sacred readings brought many problems to her curious mind, and she was not always able to clarify them. She realized that the answers could come to her only from a specialist, someone who knew the sacred languages. Thus the arrival of Jerome in Rome filled her with joy. But how to meet him? This was not an easy thing to arrange. His experience in the desert had made Jerome intensely shy of women. There was only one way to lure him out of his rather gruff isolation: invite him to discuss questions on the Scriptures. It was on this basis that Marcella was able to meet Jerome, and she peppered him with questions. Jerome soon realized what sort of person she was and little by little their conversations became real lessons and resumed every time them met, even when Marcella could devote little time to them. When they first met, Marcella had a great backlog of questions to resolve. She was, by then, no longer a young woman. She was a respectable widow, at least fifty years old and thus she had a mature mind and a long experience of reading and monastic life. Jerome was close to forty, at the time, and had the advantage over Marcella in science. He came directly from the east, bringing with him rare, mysterious "merchandise" that stimulated a great deal of curiosity in everyone he met, especially Marcella. Jerome was seeking disciples and now he had one, very well disposed to gain the utmost advantage from his lessons, and so he was filled with admiration for this woman who wanted to become, according to the affectionate superlative he was fond of calling her later, his great scholar, someone who could stimulate him to work harder. This Marcella was very glad to do, and she happily aided Jerome in his intellectual apostolate, whereby he attempted to find other candidates for the perfect life and sacred science. These conquests are made, however, through direct contact with people, not just by contact with the scriptures. Marcella possessed, much more than the impulsive, temperamental Jerome, a well-balanced sensitivity and a friendly disposition that were hard to resist. She knew how to placate the bristly excitement of her irascible teacher, who too easily took upon himself the role of the � spiritual surgeon�, all too willing to extirpate, with his knife, the moral wounds of his fellow men. Marcella�s interest in Jerome was so great that, if authorized, she would not have hesitated to shut his mouth with her hand when, with excessive frankness, he gave vent to words that might be considered too rude and violent. Under the circumstances, however, she was able to signal him her disapproval by a look or a gesture. When Marcella frowned, Jerome controlled his rage, fearing her reproof. How many times, without the warning of his sensible student, his freedom of language and pen would have got him in the worst of trouble!

A queste rare qualit�, Marcella univa quella di caposcuola. La sua volont� tenace la spingeva a diffondere attorno a se i propri gusti. Ella era portata all�insegnamento. Le sue relazioni molteplici e la sua parentela molto importante le offrivano un campo di azione del tutto naturale, che Marcella sfrutt�. Tuttavia le nuove leve faticavano ad arrivare. Solo dopo molti anni dalla sua decisione di dedicarsi alla ascesi e allo studio Sofronia e altre accettarono di unirsi a lei. Paola rest� sposata almeno fino al 379. Nel 382, quando Girolamo arriv� a Roma, la comunit� dell'Aventino era gi� prospera. Egli conobbe Marcella "circondata da vergini, da vedove e da donne conquistate alla vita austera ". La stessa Albina ora seguiva l'apostolato intellettuale della figlia con una simpatia molto intensa. Girolamo la circondava di molte attenzioni; ne elogiava le finezza di spirito e la considerava un po' come sua seconda madre.

To these rare qualities, Marcella added that of leadership. Her tenacious will prompted her to speak of her interests to all she knew. She had a talent for teaching. Her many friends and important relatives offered her a natural field of action, that she never hesitated to take advantage of. But new pupils came very slowly. It was only after many years of study and asceticism that Sophronia and others agreed to join her. Paula was married at least until 379. In 382, when Jerome arrived in Rome the Aventine community was already numerous. He met Marcella " surrounded by maidens, widows and women devoted to the life of austerity ". Even Albina now accepted the intellectual apostolate of her daughter with serenity. Jerome became very fond of her and praised her fineness of spirit, considering her as sort of a second mother.

Non sembra che Marcella abbia avuto al suo fianco fin da allora Principia. Ben presto per� non potr� fame a meno e diventer� la sua copia, dopo esserle stata allieva. Il maestro conobbe solo attraverso la corrispondenza questo " fiore di Cristo". Non potendola introdurre di persona "nei prati verdeggianti delle Scritture ", si compiacer� tuttavia di considerarla come sua figlia molto santa e seria.

It does not appear that Principia was part of Marcella�s little community at that time. Soon she could not help herself and became a copy of her, after being her student. The master knew her only through his correspondence with this " flower of Christ". Though he could not introduce her personally "to the green pastures of the Scriptures", he always liked to consider her one of his most saintly and serious daughters.

Marcellina, probabilmente sorella di Ambrogio di Milano, Felicita la santa, la vergine Feliciana e la vedova Lea, che presiedeva un monastero, facevano parte di questo gruppo che Marcella riuniva attorno a s� sull'Aventino. Rimpiangiamo la discrezione di Girolamo a loro riguardo. Si limita a nominarle semplicemente, alla fine di una lettera. Lea mor� quando egli era a Roma: and� tra le prime a controllare nella citt� di Dio, scrive Girolamo con il suo linguaggio mistico, ci� che l'insegnamento del maestro le aveva permesso di intravvedere quaggi� circa le realt� del mondo futuro. Questa circostanza ci ha consentito di conoscere il suo elogio.

Marcellina, who was probably one of the sisters of Ambrose of Milan, Felicita the saint, the virgin Feliciana and the widow Lea, who presided over a monastery, were part of this group that Marcella gathered around her on the Aventino. We can only regret Jerome�s discretion with regard to them. He simply names them, at the end of one letter. Lea died while he was still in Rome: she was one of the first to go and see in the city of God, writes Jerome with his mystical language, what the teachings of the master had enabled her to glimpse here on earth about the reality of the future world. This circumstance has permitted us to have his eulogy of her.

Asella, sua confidente, � stata ancora pi� favorita; Girolamo ne ha tessuto l'elogio quando era ancora in vita. Ma molte altre hanno seguito le sue lezioni, secondo quanto egli stesso ammette.

Asella, Marcella�s dearest friend and confidant, was even more privileged: Jerome sang her praises while she was still alive. But many other women attended his lessons, as he himself admits.

In realt� Girolamo ci ha parlato solo delle sue alunne preferite. La sua simpatia andava di preferenza, com'� naturale, a quelle che rispondevano meglio al suo insegnamento. Maestro estremamente sagace, aveva il dono di penetrare le anime. Tra il suo folto uditorio, sulla base dei quesiti posti e della stessa fisionomia, era abilissimo a discernere le qualit� dell'intelligenza. Uno studioso di storia della chiesa antica, non senza una punta di malizia, scrive che quando Girolamo si sentiva capito, "provava la gioia pi� pura, propria delle persone come lui: la gioia di vedere che la scienza serviva a qualche cosa ". A queste persone eccezionali, capaci di rendere di pi�, egli riservava una particolarissima attenzione. Facilmente e giustamente si entusiasmava per loro.

Actually, Jerome only speaks to us of his favorites. As is natural, his preference went to those who responded best to his teachings. He was an extremely sagacious master and had the gift of being able to penetrate the soul. In a crowd of listeners, on the basis of the questions asked and even the expression, he was highly skilled at picking out the most intelligent ones. A scholar of ancient church history writes, not without a hint of malice, that when Jerome felt his listeners understood him, "he experienced the purest of joy, a property of men like him: the joy of seeing that knowledge served a purpose". He reserved for these exceptional people, the ones who gave the most for what they got, a very special sort of attention. He became enthusiastic about them easily and rightly.

Fu cos� che la vedova Paola ebbe il dono di interessarlo in modo speciale: desider� conoscerla. Certamente Marcella si offr� ad introdurlo presso di lei. Infatti, Paola fu una delle sue pi� nobili conquiste di Girolamo. Marcella aveva portato nella casa di Paola la scintilla che ivi doveva irradiare un cos� santo ardore per la vita perfetta e le aveva comunicato il suo fervore per le pratiche ascetiche. D'altra parte, Paola non aveva avuto molto da fare. La morte del marito, lungi dall'esserle stata indifferente come molti pensano, l�aveva invece gettata in una profonda tristezza, in una noia mortale. Ormai pi� nulla le interessava. La vita rumorosa la stancava. Non pensava che a liberarsene "per dedicarsi alla preghiera senza importune distrazioni, per digiunare, per leggere ogni giorno la Scrittura con la mente sgombra". Quest'ultimo interesse l'attirava pi� di ogni altro. E fu proprio coinvolgendola nel suo gusto per le sante Scritture che Marcella, a poco a poco, l'aveva conquistata.

This was how the widow Paula came to interest him in a special way: he wished to meet her. Undoubtedly Marcella offered to introduce them. As it turned out, Paula was one of his most noble conquests. Marcella had taken to Paula�s house the spark that would light the saintliest of ardors for the perfect life and had transmitted to Paula her own fervor for ascetic practices. At that time, Paula did not have much to do. The death of her husband, far from leaving her indifferent as many think, had indeed cast her into a state of deep despair and inertia. Nothing interested her any more. She found an active life tiring. Her only desire was to free herself of it "to devote her life to prayer without worldly distractions, to fast, to read the scriptures every day with an open mind". This last desire was the one that attracted her the most. And it was just by catering to her taste for the sacred scriptures that Marcella, little by little, succeeded in winning her over.

Paola aveva molti figli, e ben disposti a seguirla nella sua vita di studio e di penitenza. La figlia primogenita, Blesilla, vedova a soli vent'anni, era quasi un prodigio. Possedeva un insieme di qualit� che ben raramente si riscontrano insieme a quell'et�. Girolamo ne rilev� subito "il gusto per la preghiera, il parlare elegante, la sicurezza della memoria, la finezza dello spirito ". Tutte queste doti incantarono e conquistarono, Girolamo, il maestro. Purtroppo egli tard� molto tempo a conoscerla, sufficiente comunque per rimpiangere poi la sua prematura scomparsa, piangendola nel profondo del cuore insieme alla sua madre. Infatti Blesilla mor� presto. Apparteneva a quelle nature precocemente dotate, mature prima dell'et�, nelle quali spesso si produce uno squilibrio tra la vita fisica e quella spirituale; l'anima cresce, in un certo senso, a spese del corpo, finendo con l'avere la meglio in poco tempo sul suo fragile involucro.

Paula had several children, all happily willing to follow her in her life of study and penitence. Her eldest daughter, Blesilla, a widow at just twenty years of age, was indeed something of a prodigy. She possessed a number of qualities that very rarely are found all in one person and at such an early age. Jerome immediately remarked " her taste for prayer, her elegant way of speaking, the sureness of her memory, the fineness of her spirit". All these gifts enchanted and conquered Jerome, the master. Unfortunately he met her late, but in time to greatly regret her untimely death, weeping for her from the bottom of his heart with her mother. Blesilla died young, one of those precocious natures that ripen before their time, in whom often there is an imbalance between the physical and spiritual life. The soul grows, in a sense, at the expense of the body and all too soon burns the life out of its fragile shell.

La seconda figlia di Paola, Paolina, aveva sposato un vecchio compagno di studi dello stesso Girolamo, il senatore Pammachio. Essi abitavano ai piedi del Celio, vicino al tempio di Claudio. Era una coppia straordinaria. Entrambi avevano un'altissima considerazione del matrimonio. In verit�, Pammachio era, per sua moglie, " un fratello pieno di affetto", pi� che uno sposo nel senso corrente della parola. Non � che vivessero continenti. Paolina non aveva esclusivamente una vocazione ascetica. Non ignorando alcuna delle sottigliezze della Scrittura, le ritornavano sempre alla mente, e ne era colpita, i consigli dell'apostolo Paolo sulla verginit� (1 Cor 7). Insomma, poco incline al matrimonio, ne aveva accettato gli obblighi nella speranza di poter aver figli da consacrare poi al Signore. Raggiunto questo scopo, si proponeva di vivere con il marito in una totale continenza, come allo stesso modo fecero altri personaggi famosi del tempo, come Melania e Piniano a Roma. Questo progetto, purtroppo, non si sarebbe mai potuto realizzare, almeno sotto questa forma. Paolina ebbe molti aborti, in seguito ai quali mor�. Essa non ebbe il figlio che aspettava; non appena Paolina mor�, Pammachio indoss� l'abito nero dei monaci. Nell'attesa, tutte queste delusioni venivano in qualche modo compensate grazie alla consolazione offerta dalle Scritture. Pammachio e Paolina le leggevano con avidit�. La prova li affinava; la loro conversazione era elevata; i loro rapporti personali erano vivificati da una intensa vita di fede. Girolamo che, secondo quanto egli stesso confessa, riusciva a giustificare il matrimonio solo nella prospettiva di generare dei vergini destinati a costituire l'onore della chiesa, non aveva tardato a capire che cosa si poteva aspettare da questa coppia straordinaria.

Paula�s second daughter, Pauline, had married an old schoolmate of Jerome�s, senator Pammachius. They lived at the feet of mount Celio, near the temple of Claudius. They were an amazing couple. Both had a very high consideration of marriage. In truth, Pammachius was, for his wife, "a loving brother ", more than a spouse in the current sense of the word. Not that they lived celibately. Pauline did not have an exclusively ascetic vocation. She was not ignorant of some of the subtleties of the scriptures, and was especially struck by the recommendations of St. Paul on virginity, which ran through her mind constantly (1 Cor 7). In short, though little inclined toward marriage, she had accepted it in the hope of having children to consecrate to the Lord. Having achieved that aim, she proposed to live with her husband in total celibacy, as many other famous personalities did at the time, like Melania and Piniano in Roma. Her dream, unfortunately, could not come true, at least in that form. Pauline had many miscarriages, and eventually died of one. She never had the child she wished for, but as soon as she died, Pammachius became a monk. During their marriage, however, all these disappointments were compensated for to some extent by the consolation offered by the scriptures. Pammachius and Pauline read them avidly. Their trials purified them, their conversation was elevated, their personal relations vivified by an intense spiritual life. Jerome who, as he himself confessed, could only conceive of marriage as a way to beget virgins destined to honor the church, was quick to understand what could be expected from such an extraordinary couple.

Egli mostrava grande interesse soprattutto a una delle figlie pi� giovani di Paola, Eustochio. Paola l'aveva incaricato di educarla. Girolamo aveva accettato con grande gioia, perch� sognava di abituare presto i figli alle pratiche ascetiche e alla lettura sacra. Marcella aveva curato personalmente i primi anni di Eustochio, la quale, avendo vissuto fino ad allora nella sua intimit�, era anche sua figlia spirituale. Il passaggio di Eustochio alle cure di Girolamo dovette sembrare piuttosto duro alla giovane fanciulla. Difatti il nuovo precettore non sempre controllava le proprie espressioni e a volte presentava i suoi consigli in forma rude e poco pudica. Tuttavia, egli trover� in Eustochio un'ottima alunna, che lo ascoltava volentieri e gli perdonava le scorrettezze di linguaggio, poich� lo ammirava. Quanto meno, Girolamo pot� formarla secondo il suo gusto e, a poco a poco, vide destarsi, nella sua anima verginale, la passione per le Scritture.

He took great interest above all in one of Paula�s younger daughters, Eustochium. Paula had asked him to educate her. Jerome accepted with joy, because his dream was to train the children at an early age in ascetic practices and the reading of the sacred scriptures. Marcella had personally attended to Eustochium�s early years, taking the girl to live with her as her spiritual child. The transfer of Eustochium to Jerome�s tutorship must have seemed a bit harsh to the young girl. Certainly her new teacher did not always control his expressions and sometimes couched his advice in rather gruff or even vulgar terms. However, he found Eustochium to be an excellent student, who listened to him willingly and forgave his rough language because she admired him. At last, Jerome could train a young mind according to his taste and have the pleasure of seeing her virginal soul awaken, infused with passion for the scriptures.

Toxozio era l'unico figlio maschio di Paola, ancora troppo giovane perch� Girolamo potesse occuparsi di lui. Pi� tardi comporr� un programma di educazione per sua figlia, la piccola Paola.

Toxozio was Paula�s only male child, still too young for Jerome to take an interest in but he later composed a plan of education for his daughter, little Paula.

Quanto a Rufina, l'ultima figlia di Paola, sappiamo ben poco delle sue disposizioni di spirito; mor� ancora giovane, quando aveva a mala pena l'et� per sposarsi.

Rufina was Paula�s youngest child. We know very little about her spiritual disposition because she died when she was barely of marriageable age.

Tra i giorni felici della sua vita, Girolamo poteva certamente contare quello in cui era entrato nella casa di Paola. Vi aveva trovato risorse inattese, una perfetta consonanza di gusti. Cos�, con la sua ricca immaginazione, che riusciva a trasfigurare tutte le cose, si compiaceva di paragonare i quattro componenti di questa famiglia ideale, una vera perla tra le famiglie romane, ai quattro destrieri del carro di cui si parla nella visione di Ezechiele.

Among the happiest days of his life, Jerome could surely count the one on which he entered the home of Paula. There he found unexpected resources, a perfect meeting of tastes. Thus, with his rich imagination that was able to pierce to the heart of all things, he liked to compare the four elements of this ideal family, a real pearl among Roman families, to the four steeds harnessed to the chariot of which Ezechiel speaks in his vision.

Li vedeva attaccati a questo " carro misterioso della santit�, correndo in modo ineguale, � vero, verso la corona celeste, ma con lo stesso ardore. Diversi anche nel colore, ma unanimi nel portare il giogo del Signore, senza bisogno di pungolo, docili solo alla voce di colui che li guidava ". Chiamava Pammachio il "vero cherubino di Ezechiele". Che avesse per lui una vera predilezione, lo si comprende facilmente. Non si dimenticano cos� presto i vecchi compagni, che hanno condiviso con noi i primi anni della vita, ancora senza preoccupazioni, "quel tempo pi� dolce della luce del giorno ", come scriveva con emozione lo stesso Girolamo. Ma Pammachio aveva altri titoli, non meno preziosi, per ottenere l'affetto dell�amico. Dopo una lunga separazione, si erano ritrovati, entrambi conquistati dallo stesso ideale ascetico: avevano rinunciato alla retorica per dedicarsi totalmente allo studio della Scrittura. Girolamo, pi� anziano nella scienza sacra, sorvegliava l'evoluzione intellettuale dell'amico. Con gli occhi sempre aperti sui suoi progressi, gli riusciva facile giudicare la profonda trasformazione della sua anima dallo stile delle sue lettere. Con sua grande gioia, Pammachio non scriveva pi� come una volta. Infiorava le lettere con citazioni bibliche, felicemente scelte. "Si nutriva ogni giorno dell'essenza dei profeti; si iniziava alla religione di Cristo, ai misteri della vita dei patriarchi ". Per Girolamo, insomma, egli era "l'amico carissimo ", "l'uomo di Dio ", che non doveva mai perdere di vista commentando le Scritture, l'uomo estremamente avido di scienza, e di apprendimento.

He saw them harnessed to this " mysterious chariot of sanctity, each pulling in its own way, it is true, toward the celestial crown, but with the same ardor. Of different colors too, but all willing to bear the yoke of the Lord, without the need of the whip, obeying the mere voice of their driver ". He called Pammachius the "true cherub of Ezechiel". It is clear that he had a special feeling for this man. Old schoolmates are not soon forgotten, when they have shared with us the first years of a life without toil or worry, "the sweetest time of daylight", wrote Jerome, movingly. But Pammachius deserved the love of his friend for other reasons, no less precious. After a long separation, they had met again, each devoured by the same ascetic ideal: they had renounced rhetoric to devote themselves entirely to the study of the scriptures. Jerome, with longer experience of sacred science, supervised the intellectual development of his friend. With his eyes always open to every progress, it was easy for him to judge the profound transformation of this soul by the style of Pammacchius�s letters. To his great joy, Pammachius no longer wrote as he once had. He embellished his letters with appropriate biblical citations. " He was nourished every day by the essence of the prophets, initiated into the religion of Christ, the mysteries of the life of the patriarchs ". For Jerome, in short, he was "my dearest friend", "the man of God", whom he must never lose sight of, commenting the scriptures, a man extremely avid for knowledge and learning.

Non abbiamo dubbi che questo primo gruppo di amici ha occupato sempre, anche in seguito, un posto particolare nel cuore di Girolamo. E ci� si spiega facilmente. L'insegnamento orale stabilisce tra maestro e alunni relazioni profonde, e imprime all'amicizia un cammino ben pi� intenso di quello che possono fare i semplici consigli dati per lettera. Per quanto personale possa essere, la lettera resta sempre un modo di comunicazione molto imperfetto. Anche se sincera, ha qualcosa di sbiadito, di convenzionale, di cui difficilmente si spoglia. La lettera non pu� mai sostituire completamente la vista e la parola. Girolamo se ne rendeva conto meglio di ogni altro. La sua sensibilit� esigente gli faceva preferire la presenza della persona; pi� volte si lamentava di dover scrivere astrattamente, senza conoscere il volto dei suoi corrispondenti. Durante il suo soggiorno a Roma, Girolamo conobbe questa gioia pura. L'immagine di Marcella, Paola, Blesilla, Eustochio e delle loro compagne, nel suo orizzonte intellettuale ormai aveva preso un rilievo incomparabile. Cos� scrive, quando commenta la Scrittura: " tu comes itineris. et excantator venenatorum morsuum, spiritualem nobis <g- _psullea_ > exhibe" (Comm. in Joel proph., Prol. PL, XXV, 948, B).

We have no doubt that this first group of friends always occupied an important place, even later, in the heart of Jerome. This is easy to understand. Oral teaching establishes a profound relationship between the teacher and his pupils, and gives friendship a much more intense aspect than mere advice given by letter. However personal it may be, a letter remains a very imperfect mode of communication. Even when it is sincere, there is something faded about it, something conventional that is hard to shake off. A letter can never completely take the place of sight and sound. Jerome knew this better than anyone else. His demanding sensitivity made him prefer the presence of the person; often he complained of having to write abstractly, without knowing the faces of his readers. During his stay in Rome, Jerome had the pure joy of seeing Marcella, Paula, Blesilla, Eustochio and their companions every day, and this had come to have an incomparable importance on his intellectual horizon. Thus he writes, commenting on the scriptures: "tu comes itineris. et excantator venenatorum morsuum, spiritualem nobis exhibe " (Comm. in Joel proph., Prol. PL, XXV, 948, B).

Girolamo aveva avuto il vantaggio che, dopo di lui, nessuno forse avrebbe potuto dire - almeno allo stesso livello, "d'essere il confidente delle persone pi� aristocratiche del suo tempo e di lavorare su una materia morale di alta qualit� ". Inoltre, queste donne colte, delicate e anche affezionate come le donne che seguivano Ges�, avevano pi� di una volta applicato sul suo cuore, addolorato per le critiche acerbe dei suoi avversari, il balsamo delle loro consolazioni. Avevano riportato il sole nella sua vita in momenti molto nuvolosi, in una citt� nella quale molti non l'avevano capito. Invece di negargli la loro fiducia quando molti se ne andavano da lui o lo detestavano, esse erano impegnate in tutti i modi a difenderlo. Da parte sua, Girolamo era rimasto attaccato a loro nonostante le chiacchiere moleste che si facevano circolare sul suo conto. Per la verit�, tutte queste circostanze esaltarono per sempre una tale amicizia.

Jerome had had the benefit that, after him, perhaps no one else would be able to claim � at least at the same level, "to have been the confidant of the most aristocratic people of his time and to work on a moral material of the highest quality". In addition, these cultured women, delicate and even affectionate as the women who followed Jesus, had more than once applied the balm of their consolation to his heart, wounded by the criticism of his adversaries. They had brought the sun into his life in very stormy times, in a city where many failed to understand him. Instead of withholding their trust when many turned their backs on him and despised him, they were committed in every way to defending him. On his part, Jerome remained attached to them in spite of the malicious gossip that circulated about his circle. Indeed, all these circumstances only exalted those friendships forever.

Fabiola, l'erede della famiglia Fabia, non volle essere da meno delle sue pie amiche. Si era messa ai margini della societ� cristiana, convolando a seconde nozze mentre era ancora vivo il suo indegno sposo. Ma, dopo aver terminato la sua eroica penitenza alla porta della basilica lateranense, rimpiangendo di non aver ricevuto l'insegnamento diretto di un maestro che aveva lasciato a Roma simili ricordi, si imbarc� poi per Gerusalemme, con il marito Oceano, per vedere Girolamo. Il suo soggiorno a Betlemme fu una lunga lezione di esegesi, troppo presto interrotta dall'arrivo degli Unni, che l'obbligarono a ritornare in fretta a Roma. Girolamo aveva forse davanti a se un'altra Marcella, cos� ardente per lo studio sacro, cos� difficile da accontentare. Era arrivata con una interminabile lista di quesiti, raccolti un po' ovunque nella Bibbia, che conosceva a meraviglia. Girolamo doveva rispondere a tutto; questo esigeva da lui una rara duttilit�, perch� quella donna straordinaria passava dai Profeti ai Vangeli, dai Vangeli ai Salmi con una rapidit� sconcertante. Anche il miglior professore avrebbe potuto farsi cogliere alla sprovvista. Girolamo stesso, a volte, era costretto a confessare la sua ignoranza o, quanto meno, a darle risposte provvisorie, di cui avvertiva l'inadeguatezza. Fabiola era portata a considerare di preferenza l'aspetto pi� complesso delle cose, come certuni che hanno della verit� una visione piena di sfumature, per cui permangono in uno stato di continua perplessit�. Non � certo questione di orgoglio una simile posizione intellettuale; anzi spesso � accompagnata da grande umilt� e da una specie di timidezza e di perenne esitazione, componente di fondo della loro natura. Comunque Fabiola, tanto difficile da accontentare, non esitava a riconoscersi indegna di penetrare il mistero delle Scritture. Ma era ansiosa, e l'inquietudine del suo spirito resisteva a tutto. Pi� sapeva e pi� desiderava sapere. E le risposte di Girolamo, lungi dall'appagarla completamente, la invogliavano invece a chiedere ancora di pi�. Ogni sua risposta era, per la sua intelligenza, come l'olio per il fuoco: un modo di attizzarlo, di aumentarne l'ardore. Fabiola era incapace di gustare a lungo la pace dello spirito. "Buon Ges� -doveva un giorno esclamare Girolamo ricordando questa visitatrice insigne dal desiderio intellettuale insaziabile - che ardore metteva nello studio dei Libri santi! ".

Fabiola, heiress of the Fabia family, did not want to do less than her pious friends. She stood on the outskirts of Christian society, taking a second husband while her first unworthy spouse was still alive. But after terminating her heroic penance at the gates of the Lateran basilica, regretting that she had never benefited from the direct teachings of a master who had left such powerful memories in Rome, she embarked for Jerusalem, with her husband Oceanus, to see Jerome. Her stay in Bethlehem was a long lesson of exegesis, interrupted too soon by the arrival of the Huns, that forced her to return in haste to Rome. Jerome had perhaps found another Marcella, so ardent for sacred studies, so difficult to please. She had arrived with an interminable list of questions, drawn from almost every part of the Bible, which she knew amazingly well. Jerome had to answer them all, which demanded a rare docility on his part, since this amazing woman skipped from the Prophets to the Gospels, from the Gospels to the Psalms with disconcerting speed. Even the greatest professor might have revealed gaps in his knowledge, and Jerome was occasionally forced to confess that he did not have the answer or that, at best he would have to give a provisional answer which he realized was inadequate. Fabiola was one of those people who tend to prefer the most complex aspect of things, like those whose vision of truth is full of shadings so that they remain in a permanent state of perplexity. It is certainly not a question of pride to hold this type of intellectual position, quite the opposite if we consider that it is often accompanied by great humility and a sort of timidity and perennial hesitation, which seem to be a fundamental part of the nature of such people. In any case Fabiola, so hard to please, was also quick to admit that she was unworthy to penetrate the mysteries of the Scriptures. But she wanted to, all the same, and the restlessness of her spirit forced her to continue, resisting all obstacles. The more she knew the more she wanted to know. And Jerome�s responses, far from satisfying her completely only stimulated her to ask more. His every answer was, for her intelligence, like oil on a fire, a way of stirring it up and increasing its heat. Fabiola was not capable of enjoying spiritual peace for any length of time. "Good Lord � exclaimed Jerome one day, remembering this illustrious visitor with her insatiable intellectual desire � what ardor she had in her studies of the sacred Scriptures! "

La vedova Furia e la vergine Demetriade, uscite entrambe dall'ambiente aristocratico, entrarono in relazione con Girolamo, la prima nel 394 e l'altra pi� tardi, nel 414. Esse completano la galleria delle persone illustri di cui Girolamo fu sia il direttore di coscienza che il dotto professore.

The widow Furia and the virgin Demetriade, both from aristocratic circles, became disciples of Jerome, the first in 394, and the other later, in 414. These completed the gallery of illustrious women for whom Jerome was as much spiritual director as he was learned professor.

Si sar� gi� potuto notare che l'uditorio di Girolamo era praticamente tutto femminile. Attorno a lui non sono mancati coloro che se ne meravigliavano. Chi aveva la voglia di malignare, prese l'occasione da questo fatto per accusare il giovane professore di preferire troppo ostentatamente il sesso debole al proprio. A costoro egli rispondeva che la curiosit� � minore negli uomini che nelle donne: " Se gli uomini mi ponessero dei quesiti sulle Scritture, diceva, io non mi dedicherei pi� alle donne ".

It will by now be obvious that most of Jerome�s disciples where women. There were those around him who could not help but be surprised by this. The more malicious commented that the young professor seemed to prefer to teach the weaker sex rather than his own. To them he replied that men have less curiosity than women: " If men asked me the kind of questions about the scriptures that women do, he said, I would not devote so much of my time to women ".

Girolamo constatava questo stato di cose. Lo giustificava anche, mostrando il ruolo importante svolto dalle donne nell'Antico e nel Nuovo Testamento, al punto da dare, a volte, lezione agli uomini. Infine, quando i critici gli facevano perdere la pazienza, dichiarava che "La virt� non ha sesso e che Cristo, accettando le cure delle sante donne, lasciando le tre Marie ai piedi della croce e facendo di Maria Maddalena il primo testimone della sua risurrezione, aveva aperto la sua religione alle donne".

Jerome himself was aware of this and justified it too, pointing to the important role of women in the old and new Testament, to the extent that sometimes the women were capable of teaching the men a lesson. At last, when his critics drove him to lose his temper, he pointed out that "Virtue is sexless and Christ, by accepting the ministrations of the holy women, leaving the three Marys at the foot of the cross and letting Mary Magdalene be the first witness of his resurrection, had clearly opened his religion to women ".

Trans. Katherine Fay

A site which discusses the Codex Argenteus: http://www.ub.uu.se/arv/codexeng.cfm

IL CODEX ARGENTEUS: UN SAGGIO Di CODICOLOGIA

THE CODEX ARGENTEUS: AN ESSAY IN CODICOLOGY

PROF. JAMES MARCHAND, UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS, CHAMPAGNE-URBANA

The most important of the Germanic languages from the standpoint of comparative linguistics is Gothic, and the most important of the manuscripts of Gothic is the CODEX ARGENTEUS ("Silver Codex", because written in silver andagoldaink onapurple parchment), presumably produced in Italy (Ravenna) in the early 6th century (Marchand 1969; Handout I). It is the result of a translation of the Greek New Testament into Gothic, made by Bishop Wulfila (ca. 311-ca. 383) in the 4th Century. Wulfila was a lector before he became a bishop, and it is quite likely that he made use of the lectionary devices available in the 4th century, though we cannot, of course, be sure (Marchand 1956; Handout II). He devised, for example, an alphabet in which to write the Gothic language, though we may be fairly sure that the alphabet used in the CODEX ARGENTEUS differs somewhat from his (Fairbanks and Magoun; Handout III). For example, the form of the and the fact that we have a suspension mark for both and reveal Latin influence. The fact that the manuscript is written on purple parchment with gold and silver ink, perhaps on uterine parchment, along with the form of the arches at the bottom of each page, which resemble those of Theodoric's castle in Ravenna, has led scholars to believe that it was produced at the court of Theodoric.

La pi� importante delle lingue germaniche dal punto di vista della linguistica comparata � il gotico, e il pi� importante dei manoscritti della lingua gotica � il CODEX ARGENTEUS ("Codice argenteo", perch� scritto con inchiostro argento e oro su pergamena porpora) presumibilmente prodotto in Italia (a Ravenna) agli inizi del VI secolo ( Marchand 1969; Foglio I). E' il risultato di una traduzione del Nuovo Testamento greco in gotico, fatta dal vescovo Wulfila (circa 311- circa 383) nel IV secolo. Wulfila fu lettore prima di divenire vescovo, ed � molto probabile che si serv� delle indicazioni dei lezionari disponibili nel quarto secolo, sebbene non possiamo, naturalmente esserne certi (Marchand 1956; Foglio II). Egli ide�, ad esempio, un alfabeto con il quale scrivere la lingua gotica, sebbene possiamo essere abbastanza certi che l'alfabeto usato nel CODEX ARGENTEUS differisce alquanto dal suo (Fairbanks e Magoun; Foglio III). Ad esempio, la forma della e il fatto che abbiamo un segno di sospensione sia per sia per rivela un'influenza latina. Il fatto che il manoscritto sia scritto su pergamena porpora con inchiostro oro e argento, forse su velino, unitamente al motivo degli archi sul fondo di ciascuna pagina, che ricordano gli archi del castello di Teodorico a Ravenna, ha indotto gli esperti a credere che fu allestito alla corte di Teodorico.

Unfortunately, the manuscript has undergone harsh treatment at the hands of time and of its various possessors. We cannot be sure as to its original size (see below), but at present only 187(8) leaves are extant. The original color has faded, some of the ink has flaked off, and it has suffered from the binder's knife. It shows underlinings and marginal and interlinear remarks by various users, mainly Junius, and once even suffered from attempts to falsify it by manufacturing silver ink and overwriting some of its letters (Handout IV).

Purtroppo, il manoscritto ha subito un duro trattamento per l'azione del tempo e ad opera dei suoi diversi possessori. Non possiamo essere certi per quanto concerne la sua dimensione originaria (si veda sotto), ma attualmente soltanto 187(8) fogli si sono conservati. Il colore originario � sbiadito, parte dell'inchiostro si � sfaldato ed ha subito danni a causa del coltello del rilegatore. Esso rivela sottolineature e annotazioni ai margini e tra riga e riga per mano di diversi fruitori, soprattutto Junius, ed in una occasione ha subito danni a causa di tentativi fatti per contraffarlo preparando inchiostro argento e riscrivendo sopra alcune delle sue lettere (foglio IV).

Editing. For almost a century, the standard edition has been that of Wilhelm Streitberg (Handout V). The fact that it has lasted so long and still has no competitor witnesses to its excellences, but it has grievous faults. It is accompanied by a reconstructed Greek text, leaning heavily on the theories of von Soden, and it had detractors from the beginning, e. g. Lietzmann and J�licher (Handout VI), to mention only two of the most prominent. From a codicological standpoint:

Revisione. Per quasi un secolo, l'edizione standard � stata quella di Wilhelm Streitberg (Foglio V). Il fatto che abbia continuato ad essere valida per cos� lungo tempo e ancora non abbia alcun eguale ne attesta i pregi, nondimeno presenta dei gravi difetti. Essa � accompagnata da un testo greco ricomposto, che si appoggia pesantemente sulle ipotesi di von Soden, ed ebbe detrattori fin dall'inizio, ad esempio Lietzmann e Julicher (foglio VI), per menzionare solo due dei pi� autorevoli. Da un punto di vista codicologico:

1. It is not careful with the conversion of the Gothic alphabet to Latin, for example making no distinction between and <�>, where Gothic makes a careful distinction. Naturally Streitberg inserts spaces between what he considers to be words (Gothic is written scriptura continua). He often inserts <-> between morphemes, e.g. ga-u-hva-sehvi (Mk 8:23). He offers no indication of the Eusebian Canons and discards the punctuation of the original in favor of his own, inserting the modern notation as to chapter and verse. This means, of course, that the user of his edition has no way of finding out what the original looked like.

1. Non � accurata nella traslitterazione dall'alfabeto gotico al latino, ad esempio, non facendo alcuna distinzione tra ed <�>, laddove il gotico segnala una netta distinzione. Naturalmente Streitberg inserisce spazi tra quelle che lui considera parole (il gotico � definito scriptura continua)_._Sovente inserisce <-> tra i morfemi, ad esempio ga-u-hva-sehvi (Marc. 8:23). Non d� alcuna indicazione dei canoni di Eusebio e abbandona la punteggiatura dell'originale a favore della sua propria, inserendo la notazione moderna per quanto concerne capitoli e versi. Questo significa, naturalmente, che il fruitore della sua edizione non ha alcun modo di scoprire che aspetto avesse l'originale.

A somewhat better edition from a codicological standpoint is that of Uppstr�m (Handout VII). He preserves the punctuation of the original, for which he was roundly excoriated by von der Gabelentz and Loebe. He also gives in the margin the Eusebian Canon number for each passage. He uses for <�> (Wulfila's sign for our [hw] sound, sometimes replaced by the so-called Collitz letter), which is perfectly all right, since his transliteration is one for one, including distinguishing between Wulfila's and <�>.

Una edizione alquanto migliore da un punto di vista codicologico � quella di Uppstr''m (FoglioVII). Egli preserva la punteggiatura dell'originale, motivo per cui fu molto aspramente criticato da von der Gabelentz e Loebe. D� anche in margine il numero del canone di Eusebio per ciascun passo. Usa per <�> (il segno di Wulfila per il nostro suono [hw], talora sostituito dalla cos� detta lettera Collitz), cosa perfettamente corretta dal momento che la sua traslitterazione � da uno a uno, includendo la distinzione tra e <�> di Wulfila.

In his frequently quoted article, "`Epistul� Venerunt Parum Duces'" Father Boyle makes a plea for more codicological information in the edition (Handout VII):

...to me codicology in its full colours is an examination of the codex as a carrier of a text. If, as is the general tendency, one simply extracts a text from a codex, then the text is bereft of its setting, and the codex is ignored. If, on the contrary, one concentrates on the physical make-up of a codex, then the danger is that the codex will be treated in isolation from the text, as though it were any codex, and not just this specific codex carrying this specific text. Codicology, then, must include the text - not of course the text as text, but as physically carried by the codex whether this be the size of the columns, the spirals of the initials, the annotations, or indeed, the smudges of the readers.

Padre Boyle nel suo articolo frequentemente citato Epistulae Venerunt Parum Duces fa una appassionata richiesta perch� vi siano pi� dati codicologici nella edizione (Foglio VII):

... per me la codicologia nella sua reale essenza � uno studio del codice come vettore che veicola un testo. Se, secondo la tendenza generale, si estrae dal codice soltanto il testo allora il testo � privo della sua cornice, ed il codice � ignorato. Se, al contrario, ci si concentra sull'allestimento fisico di un codice, allora il rischio � che il codice sia trattato separatamente dal testo, come se si tratasse di un codice qualsiasi, e non proprio di questo specifico codice che veicola questo specifico testo. La Codicologia, dunque, deve includere il testo - non ovviamente il testo come testo in se stesso, ma come testo trasportato fisicamente dal codice, sia che questo consista nell'insieme delle dimensioni delle colonne, nelle spirali delle iniziali, nelle chiose, o invero negli scarabbocchi dei lettori.

I disagree only in one point with this statement, in that I think that, where possible, a reconstitution of the original, removing later (especially modern) interventions, such as "annotations of the readers." Of course, it is important to follow Junius as he tries to come to grips with the text, but his marginal notes and underlinings can be treated in another, more appropriate, place. The CODEX ARGENTEUS is a splendid example of its age and the Gothic civilization which produced it. It should be allowed to stand forth in its original splendor, and the computer has given us the means whereby we can do this. Let me first tell you something about the manuscript and show you two reconstituted leaves. Of course, my codicological remarks cannot equal those of the splendid facsimile edition put out by Uppsala University in 1928, nor the remarks of von Friesen and Grape, to which I refer you for more information (Handout VIII).

Dissento solo su un punto con questa affermazione per il fatto che, dove questo sia possibile, ho in mente, una ricostruzione dell'originale, eliminando interventi pi� tardi (soprattutto moderni), come le "annotazioni dei lettori". Naturalmente, � importante seguire Junius mentre cerca di affrontare il testo, ma le sue glosse poste a margine e le sottolineature possono essere trattate in altro e pi� appropriato luogo. Il CODEX ARGENTEUS � uno splendido esempio del suo tempo e della civilt� gotica che l'ha prodotto. Dovrebbe essere data l'opportunit� di farlo risaltare nel suo originario splendore, ed il computer ci ha dato gli strumenti tramite i quali poterlo fare. Inizio col dire qualcosa del manoscritto e col mostrare due fogli ricomposti.. Ovviamente, le mie osservazioni codicologiche non possono eguagliare quelle della splendida edizione facsimile pubblicata dall'Universit� di Uppsala nel 1928, n� le osservazioni di von Friesen e Grape, alle quali rimando per ulteriori informazioni.

Preparation of Parchment . Professsor Erik Agduhr's investigations into the parchment are reported on by von Friesen and Grape (p. 1), and they report that it is his opinion that it is uterine vellum, of the skin of newly-born or unborn calves. The skin was dyed purple, probably according to the method recommended by Pliny (Steigerwald). It has faded greatly, and von Friesen and Grape's attempt to register the early twentieth-century color by the use of the plates of Klincksieck and Valette is not very reliable. The Code des couleurs not only is hard to come by, its colors seem also to have changed at times. A new registration of the present-day colors using spectrographic analysis is needed. The pages given here have the color of royal purple according to my own investigations, using modern-day murices. Von Friesen and Grape are of the opinion that the original color varied between quite dark red and red-violet. Of course, the computer color can be changed at will. For a partial list of the colors available by computer, see Rogondino (Handout IX).

Preparazione della pergamena. Le indagini del professor Erik Agduhr sulla pergamena sono riportate da von Friesen e Grape (p.1), ci riferiscono della sua convinzione che si tratti di velino, vale a dire di una pergamena fabbricata con pelli di vitelli appena nati o abortiti. La pelle fu tinta color porpora, presumibilmente secondo il metodo suggerito da Plinio (Steigerwald). E' notevolmente sbiadita e il tentativo di von Friesen e Grape di inviduarne il colore attraverso l'utilizzo delle tavole di Klincksieck e Valette degli inizi del XX secolo non � molto attendibile. Il Code des couleurs non solo � difficile da trovare, i suoi colori pare siano anche talvolta alterati. E' necessaria una nuova registrazione dei colori correnti valendosi dell'analisi spettrografica. Dalle ricerche da me compiute risulta che le pagine qui presentate hanno il colore del porpora regale, attraverso l'utilizzo di murici del tempo presente.Von Friesen e Grape ritengono che il colore originario variasse fra il rosso cupo e il violetto. Naturalmente, il colore ottenuto al computer pu� essere modificato a piacere. Per una parziale lista dei colori disponibili al computer si veda Rogondino (Foglio IX).

The parchment thus obtained was cut, pricked and lined according to the usual methods. The fortunate find of the Speier leaf in October, 1970, a loose leaf taken early enough from the CODEX ARGENTEUS to have escaped the later ravages of the binder's knife, has given us the probable measurements of the original CODEX ARGENTEUS (Tj�der, 77 f.; Handout XI): 21.70 x 26.60 cm. as compared to the CA's 19.75-20.00 x 24.25-24.50. We are able thus to see how much the binding has taken away. As one can see from the reconstitution included here (Handout X) shows a mockup of a typical gathering of eight leaves (a quaternion):

La pergamena cos� ottenuta fu tagliata, punteggiata con un punteruolo e tracciata delle righe secondo il consueto metodo. La fortunata scoperta del foglio Speier nell'ottobre 1970, un foglio sciolto portato via dal CODEX ARGENTEUS, in tempo sufficientemente utile da aver evitato i pi� tardi danni causati dal coltello del rilegatore, ci ha fornito le probabili dimensioni del CODEX ARGENTEUS (Tjader, 77 f.; Foglio XI): 21.70 x 26.60 cm. in confronto a 19.75-20.00 x 24.25-24.50 del CA. Siamo cos� in grado di vedere quanto la rilegatura ha portato via. Come si pu� vedere dalla ricomposizione qui inclusa (foglio X) che mostra un modello d'impaginazione di un tipico fascicolo di otto fogli (un quaternione):

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

� � � � � � � �

F�H H�F F�H H�F F�H H�F F�H H�F

r�v r�v r�v r�v r�v r�v r�v r�v

� � � ������������������������ � � �

� � �������������������������������� � �

� ���������������������������������������� �

������������������������������������������������

{F = flesh, H = hair, r = recto, v = verso}

{F = carne, H = capelli, r = recto, v = verso}

The gatherings are marked on the right lower margin of the last page with the number of the gathering in the binding. Unfortunately, we cannot read the custos of the end of Mark on the Speyer leaf, but it seems fairly sure to have been 41. If von Friesen and Grape are right, the Canon table will have begun the volume, and the original count will have been 42, which gibes well with the Goths' well-known penchant for numerical significance, 42 being a symbolic number (Sauer, 83). Von Friesen and Grape (p. 12) point out the resemblance to the practice of the CODEX ROSSANENSIS, also a purple manuscript.

I fascicoli sono contrassegnati sul margine destro inferiore dell'ultima pagina con il numero del fascicolo nella legatura. Purtroppo, non possiamo leggere il custos della fine di Marco sul foglio di Speier, ma pare abbastanza certo che si tratti del numero 41. Se von Friesen e Grape fossero nel giusto, la tavola del Canone avrebbe aperto il volume, e l'originaria numerazione sarebbe stata 42, questo si prende ben gioco della nota inclinazione dei goti a dare significato ai numeri, essendo il 42 un numero simbolico (Sauer,83). Von Friesen e Grape (p.12) mettono in evidenza l'equivalenza con la consuetudine del CODEX ROSSANENSIS, anch'esso un manoscritto porpora.

Layout. The layout of the manuscript follows a carefully conceived aesthetic scheme. There are two vertical lines, set up to hold the indications of the Eusebian sections (see Figure 2). Between these lines there are two horizontal systems: an upper system to hold the text, and a lower system to contain the indications of parallel passages. The writing surface (Schriftspiegel) is prepared so that it follows the Golden Mean (von Friesen & Grape, p. 11), that is 21 cm. in height by 13 cm. in width. There are 20 lines to the page. Von Friesen and Grape also point out that the arches at the bottom of the page are also constructed according to the Golden Mean. As you can see from Figure 1, the result is breathtaking.

Impaginazione. L'impaginazione del manoscritto segue uno schema estetico accuratamente concepito. Vi sono due righe verticali realizzate per sostenere le indicazioni delle sezioni di Eusebio (si veda Figura 2). Tra queste linee vi sono due intrecci orizzontali: un intreccio superiore per sostenere il testo, e una orditura inferiore per contenere le indicazioni di passi paralleli. La superficie destinata alla scrittura (Schriftspiegel) � approntata cos� da seguire il principio dell'Aurea Mediocritas (von Friesen & Grape (p. 11), vale a dire 21 cm. di altezza per 13 cm. di base. Vi sono venti righe nella pagina. Von Friesen e Grape fannno anche notare che gli archi in fondo alla pagina sono composti in armonia con l'Aurea Mediocritas. Come si pu� vedere dalla Figura 1, l'effetto � mozzafiato.

Binding. We can tell little about the original binding, though some purple threads are left. We do know from the canons and other information that the gospels were bound in the 'Western order', that is, MtJnLkMk, and we can tell that it has been rebound, perhaps a number of times. When the manuscript came to Junius, it had been rebound in the 'normal' order, and badly, as he complained a number of times, both in his dedication to de la Gardie and in the very margins of the CODEX ARGENTEUS (Handout XII). This means, of course, that Matthew, which was always on the outside, has suffered the most, whereas Luke, which was always on the inside, has suffered the least.

Rilegatura. Possiamo dir poco per quanto concerne la rilegatura originaria, sebbene siano rimasti alcuni fili porpora. Sappiamo dai canoni e da altri dati che i vangeli furono rilegati secondo l'"ordine occidentale", vale a dire, Mt.Gv.Lc.Mc., e possiamo dire che � stato rilegato forse molte volte. Quando il manoscritto giunse a Junius era stato rilegato molte volte secondo l'ordine "conforme alla consuetudine", e male, come egli ebbe a lamentarsi, sia nella sua dedica a de la Gardie sia negli stessi margini del CODEX ARGENTEUS (Foglio XII). Questo significa, naturalmente, che Matteo, che era collocato sempre nella parte esterna, ha subito danni maggiori, laddove Luca, collocato sempre all'interno, risulta meno danneggiato .

Divisions of the Text . The text is, as you can see from both figures, divided into the Eusebian canons. The canon number is noted in the left margin, and, following Eusebius's advice, the beginning of the particular section is in gold to the end of the line. The sections agree fairly well with the usual Eusebian canons. The text is punctuated per cola et commata , with the raised dot used for the comma, and the double dot (:) for the colon. Since Wulfila was a lector before he became bishop (chorepiscopus), it seems quite likely that he is the one who devised the system of punctuation and who adopted the Eusebian canons (Marchand, 1956). The parallel sections in the other gospels are indicated in arches at the bottom of the page, one of the things which gives the CODEX ARGENTEUS its stately appearance. There are various enlarged letters found throughout, often without our being able to fathom their use.

Divisioni del testo. Il testo, come si pu� vedere da entrambe le figure, � diviso nei canoni di Eusebio. Il numero di canone � annotato sul margine sinistro, e, seguendo l'indicazione di Eusebio, l'inizio della sezione specifica � in oro sino alla fine del rigo. Le sezioni si accordano abbastanza bene con i consueti canoni di Eusebio. Il testo � punteggiato per cola e commata, con il puntino in rilievo impiegato per la virgola, e il doppio puntino per i due punti. Dal momento che Wulfila fu lettore prima di divenire vescovo (chorepiscopus ), pare abbastanza probabile che fu proprio lui ad ideare il sistema della punteggiatura e ad adottare i canoni di Eusebio. Le sezioni parallele negli altri vangeli sono indicate con archi sul fondo della pagina, una delle cose che conferisce al CODEX ARGENTEUS il suo aspetto imponenete. Vi sono varie lettere ingrandite dall'inizio alla fine, spesso senza che noi siamo in grado di comprendere a fondo il loro utilizzo.

Script. The CODEX ARGENTEUS is written in an alphabet devised by Wulfila, though it seems quite likely that some changes have been made in the intervening century and a half. The Gothic alphabet has two styles, one (I will call it style I) using a sigma-like -sign and a nasal suspension for n only, and the other (I will call it style II) uses the Latin and suspension marks for both n and m (Fairbanks and Magoun). The CA is written in Style II, and it seems quite likely that this is a later development, probably in Ostrogothic Italy. Various ligatures arise out of need for space, etc., and larger and smaller letters are used. There are two hands used in writing the CODEX ARGENTEUS, called Hand I and Hand II, but this is of little consequence. One notices the usual results of sharpening the quill and changing ink (see section on Ink).

Scrittura. Il CODEX ARGENTEUS � scritto utilizzando un alfabeto ideato da Wulfila, anche se pare abbastanza probabile che alcune variazioni siano state fatte nel secolo e mezzo che intercorse. L'alfabeto gotico ha due stili, uno (lo chiamer� stile I) usa un segno simile al sigma e una sospensione nasale soltanto per n, e l'altro (lo chiamer� stile II) usa il latino e segni di sospensione sia per n sia per m (Fairbanks e Magoun). Il CA � scritto nello stile II e pare abbastanza verosimile che si tratti di uno sviluppo pi� tardo, probabilmente nell'Italia ostrogotica.Varie legature originano dalla necessit� di spazio, ecc., e vengono usate lettere pi� grandi e pi� piccole. Per scrivere il CODEX ARGENTEUS vengono impiegate due grafie, una detta grafia I e l'altra grafia II, ma questo ha poca importanza. Si notano i consueti esiti determinati dall'atto di appuntire la penna e dal cambiare inchiostro (si veda la sezione sull'inchiostro).

The CODEX ARGENTEUS is written in straight-pen style, that is, with the nib of the pen either held or cut so that it is always parallel with the top edge of the page (Fairbanks and Magoun). It is to be expected that this will have changed the original shapes of the letters somewhat; e. g. there is usually no closure at the top of the . The handwriting is so regular that Ihre thought they might have used type or stencils. As an aside, it is interesting to note that the Anonymous Valesianus reports that Theodoric could not write and had to make use of a stencil.

Il CODEX ARGENTEUS � scritto in uno stile che utilizza una penna dritta, vale a dire, con la punta della penna tenuta o tagliata in modo tale che sia sempre parallela con il margine superiore della pagina (Fairbanks e Magoun). Questo deve aver alquanto modificato la forma originaria delle lettere; ad esempio solitamente non vi � chiusura al vertice della < o>. La scrittura � cos� regolare che Ihre ha supposto che potessero essere stati utilizzati caratteri o stampini. Facendo una digressione, � interessante notare che l'Anonimo Valesiano riporta che Teodorico non era in grado di scrivere e doveva utilizzare uno stampino.

Ink. There is little to say about the ink, other than that it is silver and gold . Gold is used for the first three lines of the beginning of each gospel, to judge from Luke and Mark (Figure 1). The beginning of each Eusebian section is written in gold to the end of the line. The monograms of the evangelists in the Eusebian arches are written in gold. What is interesting about the ink, however, is that there are two types of silver ink. Although Matthew-John, Luke-Mark are related in textual matters, Matthew- Luke, John-Mark are related as to ink. The only assumption is that they were written in the same scriptorium, and that there were two scribes at work, one copying Matthew, the other Luke. The same two scribes did John and Mark, but had to change ink, for whatever reason (Friedrichsen). A small codicological point, but important for the history of the text.

Inchiostro. C'� poco da dire per quanto concerne l'inchiostro, se non che si tratta di inchiostro argento ed oro. L'oro � usato per le prime tre righe dell'inizio di ogni vangelo, a giudicare da Luca e Marco (Figura 1). L'inizio di ogni sezione di Eusebio � scritto in oro sino alla fine del rigo. I monogrammi degli evangelisti negli archi di Eusebio sono scritti in oro. Quello che � interessante in riferimento all'inchiostro, tuttavia, � che vi sono due tipi di inchiostro argento. Quantunque Matteo-Giovanni, Luca-Marco siano strettamente congiunti per motivi testuali, Matteo-Luca, Giovanni-Marco sono strettamente connessi per quanto concerne l'inchiostro. L'unica probabile ipotesi � che essi furono scritti nello stesso scriptorium e ci furono due scrivani al lavoro, uno copiava Matteo, l'altro Luca. Gli stessi due scrivani realizzarono Giovanni e Marco, ma dovettero cambiare inchiostro, qualunque ne fosse stato il motivo. (Friedrichsen). Un dettaglio codicologico minimo, tuttavia importante per la storia del testo.

In a short talk such as this, I can only touch on a few of the codicological themes the CODEX ARGENTEUS calls up. I should like to end, however, with some suggestions, not only as to this manuscript, but as to all others. Now that we have 4 megapixel electronic cameras, all manuscripts ought to be photographed using these. We have arrived at the time when electronic photographs rival those done by film cameras, which was not true back in 1990 when I did the samples given here. This would have several advantages realizable immediately. The manuscripts would be registered and preserved in a better form than most facsimiles. One could use filtration in real time and eliminate the tiresome and time-consuming trips to the darkroom. Indeed, we could avoid putting all our eggs in the ultra-violet basket as it were and could see immediately which filter (monochromatic, of course) worked best. Given our storage capacity, one could preserve several photographs of each page. The resulting photographs could be stored in several places and be subjected to image enhancement techniques as they are developed, and could be made public, if the archive wished, by some sort of OPAC system. Since the originals would be preserved, use of non-algorithmic techniques, some of which I used here, would be immediately detectable, so that one could not falsify the record. I would hope that this would result in part in an attempt to recover the past glory of such Prachthandschriften as the CODEX ARGENTEUS by applying algorithms to achieve a reconstitution based on codicological research. Se non � ben trovato, � vero.