Waiting for the Rain in the House of Hunger (original) (raw)

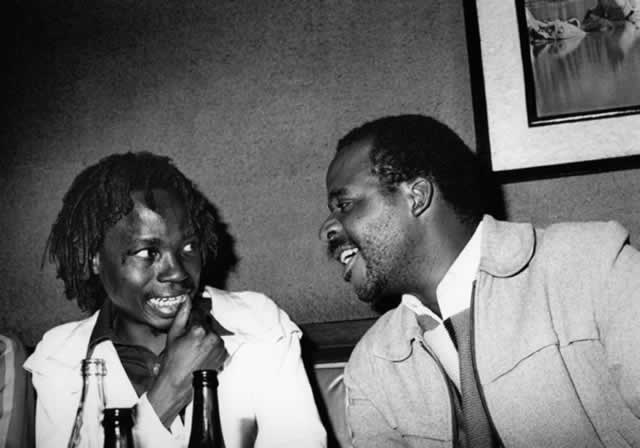

Meeting of Minds . . . Dambudzo Marechera and Charles Mungoshi

Elliot Ziwira The Book Store

BOOKS should not be judged by their covers and titles. However, the use of titles drawn from metaphors heightens critique.

The metaphors of drought and hunger, used effectively by Charles Mungoshi in “Waiting for the Rain” (1975) and “Coming of the Dry Season” (1972); and by Dambudzo Marechera in “House of Hunger”(1978), capture the spiritual, cultural, intellectual and creative crisis at the centre of the national psyche.

The spiritual malaise at the core of the Mandengu family in “Waiting for the Rain” is laid bare through a combination of imagery and symbolism.

Drought in all its forms — psychological, moral and intellectual — depicts the general neurosis which is the bane of the Zimbabwean society today.

Thus, drought and hunger, metaphors whose essence is captured by Musaemura Zimunya in “Those Years of Drought and Hunger” (1982), permeate Zimbabwean literature which makes the analysis of titles not only interesting but inevitable.

“Waiting for the Rain”, “House of Hunger”, Memory Chirere’s “Somewhere in this Country” (2006) and Shimmer Chinodya’s “Harvest of Thorns”(1989) conform to what Frantz Fanon called “literature of combat”.

The books seek the metonymic triumph of the collective voice fighting for liberation, both from internal and external forces.

Marechera’s “House of Hunger” explores the combat from within; of a family or a nation in battle against itself; a nation torn apart by violence that alienates itself, is its own foe, and presses the self-destruction button.

What this seems to suggest is that combat from within usually calls for inner strength, determination and resilience so that a lasting solution is found for the consolidation of the family, community and nation.

Hence, the individual biography is merged with the national one. As a master of understatement and irony, the rhetoric of Mungoshi’s fiction is a cut above the rest in the African tradition.

In “Waiting for the Rain”, it is imperative to distinguish the locutionary from the illocutionary, as nothing is explicit in the writer’s art.

It is the metaphorical meaning in the exploration of Mungoshi’s works which enhances the understanding of thematic concerns raised. Waiting, as pointed out by Muchemwa (2001), implies existence in limbo where everything is in abeyance. But it also suggests expectation and anxiety; that kind of feeling explored in “Waiting for Godot” and the “Enigma of Arrival”.

Waiting is predominant in the metaphorical representation of the individual and his location in the national psyche in “Waiting for the Rain”.

Rain, another metaphor in the novel, is symbolic of life giving energies that are absent in colonial Rhodesia; of political and cultural freedom and intellectual regeneration.

Rain is therefore, significant of abundance. In the novel, characters, themes and plot gain meaning when read against the metaphors waiting and rain.

The chronological plot and realistic details find their metonymic dimension transformed by the metaphorical titling of the novel.

The chronological plot is superimposed into the gathering of the Mandengu family at the rural home, to solve family problems; recharge cultural batteries and seek bearings into the future.

The Mandengu family waits anxiously for the arrival of Lucifer to bring “glad tidings” from the city. Lucifer, because of his Western education is supposed to deliver his family from the limitations of colonialism, and its oppressive and violent inclinations.

However, this waiting, which is juxtaposed with the waiting for the rain by the entire community and the nation, seem to be in vain.

Lucifer, who is supposed to be the voice of his people, fails to grasp his roots and identity. Deplorably, he is unable to locate himself either in the colonial discourse as epitomised by the transistor radio or the national discourse as embodied in the “drum”.

Therefore, the malaise and paralysis of the Mandengu family and their failure to find a lasting solution is a culmination of Lucifer’s struggles to identify himself.

The family unit is thus used as metonymic to the general problems of colonialism which affect the nation.

Kuruku aptly captures this futility when he says: “A few more years of waiting won’t make the slightest difference from what we have seen of them”.

Mungoshi’s use of names also brings to the fore the futility of waiting.

Names like Tongoona, Matandangoma, Mandisa, Japi and Kuruku, carry meanings that transform characters into symbols of different aspects of the national psyche waiting for regeneration. The general air of expectation in the novel is captured by Tongoona’s wait-and-see attitude, as his name suggests. As both an individual and father, he has been incapacitated by the belief that some external force will bring change in the family fortunes.

It is this passivity that tragically alienates Lucifer, who feels that a society incapable of change is one that has irredeemably destroyed itself.

This rationale obtains, also, in the way people in the bus look through the window at the barren, sandy and overworked land to which they feel a spiritual connectedness as is illuminated in the following: “This is our country, the people say with sad familiarity, the way an undertaker would talk of death, Lucifer thinks”.

Matandangoma skeptically stands for charlatanism; and as she presides over the family ceremony, the efficacy of her classical discourse and spiritualism become doubtful.

As aptly posited by Muchemwa (2001), charlatanism is presented at the political and intellectual levels that promises false solutions to the malaise at the heart of the fictional experience in the novel.

Kuruku, an urbane demagogue, is as untrustworthy as his name suggests. Driven by self-interest, therefore, it will be folly for a family or nation to pin its hopes on such an individual.

Lucifer, the fallen angel, distances himself from the family and nation as he always wishes “he had a different father”.

His rejection of home and its environs, norm less-ness and ideological conflict capture the universal neurosis and alienation evident in the novel and metaphorically apt in the title.

Dambudzo Marechera’s denial of the coherence of the family structure, its link with the community and nation at large, and his subsequent alienation from the concept of home in “House of Hunger” can be examined through his use of metaphors and images.

Thus, the thematic issues in the novella are captured through its metaphorical titling. The metaphor of the house represents the decadence of the family unit, which may cause the overall dearth of national ethos.

The use of symbolic elements which is a unique trait of modernism is a result of frustration, hopelessness, disillusionment and dissonance.

The family in “House of Hunger”, however, is devoid of such metonymic attributes of the Mandengu family in “Waiting for the Rain”, as it is fractured into several relics and traumatised by so many explosions of violence which inhibits the artist-narrator from locating himself in its boundaries.

He rejects this claustrophobic nature of the urban family which is intensely deprived of any opportunities of note.

As his identity and well-being is problematic because of deprivation, disease and scorn, the narrator dwells at the fringes of the sites of the house.

In his quest to escape from the four sites of the house, which ironically is supposed to be his home, the narrator is unsuccessful.

The escape motif fails physically and the only vent left is psychological.

Because of frustration and want of personal grandiose, the artist-hero who could be Marechera himself, fractures the chronological sequence of time and its limitations.

The hero finds his elixir in reverie, stream of consciousness and whimsicality which permits him to find order in the disorder of the house of hunger.

Because the metaphor of the house is inseparable from genre and form, he deliberately fractures it for dramatic effect and escape.

Images of disease, dirt and poverty are also used to reveal the abnormalities not only found in the literal house but the metaphorical one as well, which Rhodesia is, as is illustrated thus: “In The House of Hunger diseases were the strange irruptions of a disturbed universe. Measles or mumps were the symptoms of a malign order. Even a common cold could become a causus belli between neighbours”.