Gustav Klimt Biography - Gustav Klimt (original) (raw)

No one can doubt that the Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt was a crucial figure in art history. Paintings, murals, drawings, and other works of art by Klimt are well-known worldwide. His creations are still the reason for amazement and are awe-inspiring sensations for both art admirers and regular people.

Klimt’s works describe the female body; this is the primary, central topic. He created landscapes in addition to his figurative pieces, which included allegories and portraits. Klimt was the most affected by Japanese art and methods among the Vienna Secessionists.

He was an accomplished traditional painter of building embellishments and decorations used in architecture early in his career. However, his unique art quickly became a subject of controversy. Interest and criticism regarding his writing peaked when he created the piece for the University of Vienna. These paintings were branded as pornography back then. After that, he stopped taking on new public contracts, but his “golden phase” paintings, many of which use gold leaf, saw fresh success. Klimt’s art significantly impacted his younger friend, Egon Schiele.

No more general talks. Let’s get to the point and discuss Gustav Klimt’s biography, starting with his early years and ending with his successes and failures.

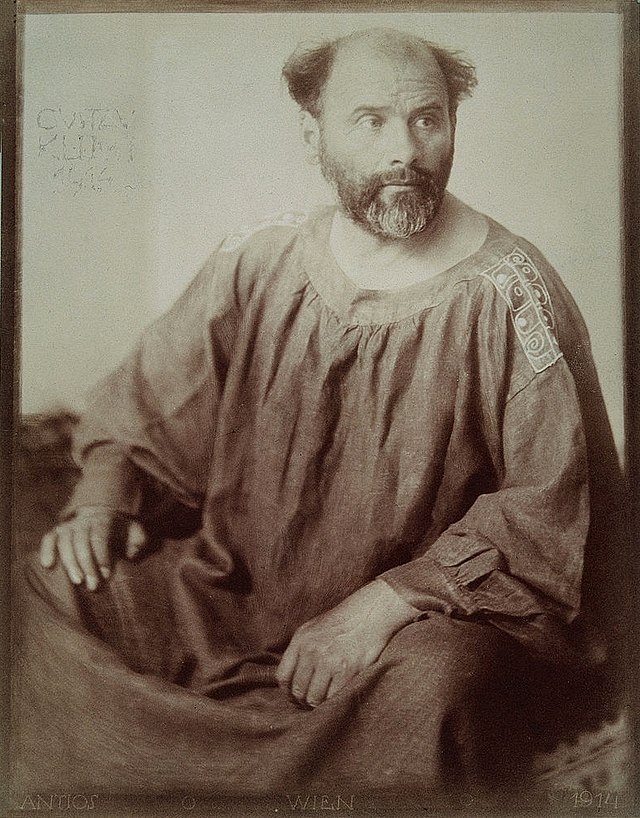

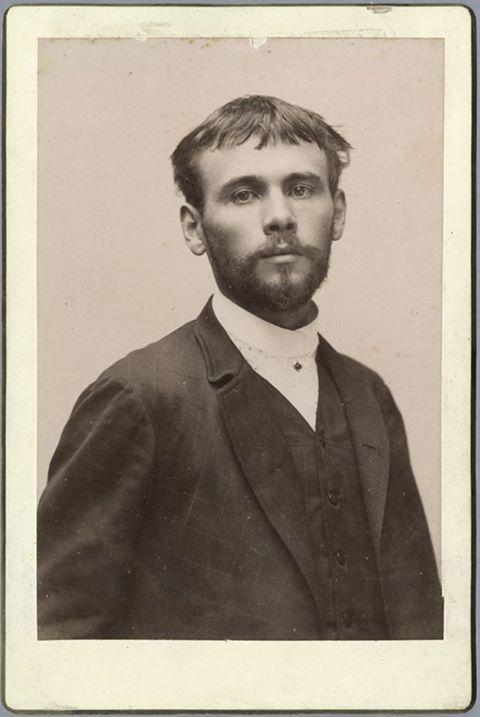

GUSTAV KLIMT

Early Life & Childhood of Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt’s biography starts with the early years of his life. He was born on July 14th, 1862, in the small district (village) of Baumgarten, located near Vienna. His parents had 7 children, and Klimt was the second oldest. There were three boys and four girls. Early on, all three sons showed ability in the arts.

Gustav Klimt’s Bohemian-born father, Ernst Klimt, was a gold engraver. The unfulfilled dream of Anna Klimt, whom Ernst married, was to perform music. Due to the challenging economic climate for immigrants, Klimt spent most of his youth in poverty. The family struggled since there were few jobs in the early Habsburg Empire, especially for ethnic minorities. The market collapse mainly caused this in the 1970s.

The Klimts lived in no less than five different places between 1862 and 1884, constantly looking for more affordable lodgings. The family had not only financial difficulties but also great sadness at home. Anna, Klimt’s younger sister, passed away in 1874 at the age of five after a protracted illness. Shortly after, his sister Klara, who had given in to religious zeal, experienced a mental breakdown.

Alongside his two brothers, Georg and Ernst, Gustav Klimt began to exhibit creative talent at a young age. But when Gustav was in secondary school, his teachers marked him as a superior draftsman. Family members persuaded him to sit for the admission test for the Kunstgewerbeschule, the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts, in October 1876, and he did so successfully. He subsequently revealed that his original plans were to become a drawing master and seek a post as a teacher at a Burgerschule, considered the equivalent of a whole public secondary school.

GUSTAV KLIMT IN 1887

How Did Klimt Begin His Artistic Career? – Education & School Years

Gustav Klimt did not oppose the rather conventional teaching methods and curriculum at the Kunstgewerbeschule. He had extensive training in drawing. However, additionally, he was also tasked with accurately reproducing the ornamentation, patterns, and plaster casts of vintage sculptures.

Only when he had established his knowledge and gathered quite an experience was he given permission to sketch figures from life. From the outset, Klimt pleased his teachers. He quickly enrolled in a special painting class where he showed great skill at painting live models and using various instruments.

As part of the young artist’s education, the school also tasked Gustav Klimt to explore and examine works and pieces by Titian and Peter Paul Rubens. Additionally, Klimt had access to the extensive collection of paintings by Spanish artist Diego Velázquez housed in the Vienna Museum of Fine Arts. Klimt was enamored by Velázquez’s work and adored it. An interesting fact is that Klimt only considered two people to be great painters, Velázquez and himself.

Hans Makart, the most well-known historical painter in Vienna then, also gained much admiration from Klimt. Klimt’s positive attitude towards the artist was especially a result of his approach, which made use of dramatic lighting effects and a clear passion for theatricality and pomp. Klimt reportedly paid one of Makart’s attendants to let him inside the painter’s studio. Back then, he was still a student. This allowed him to examine Hans Makart’s most recent works in progress.

Before he left the Kunstgewerbeschule, Ernst, Klimt’s younger brother, and Franz Matsch, a talented young painter from Vienna who specialized in large-scale ornamental works, joined Klimt’s painting class. After finishing their studies in 1883, Klimt and Matsch rented a sizable studio in Vienna.

First Steps In Professional Development

Gustav Klimt continued to live with his parents and surviving sisters despite this relocation and his early success. Klimt and Matsch quickly rose to the top of the city’s cultural elite, including eminent architects, society members, and government officials. Gustav Klimt and Matsch were suggested by Ferdinand Laufberger, their painting tutor, to embark on a four-piece assignment for a Vienna architectural business specializing in theatrical design as early as 1880.

Despite the demand, the works of Klimt and Matsch were not well paid. Klimt, Ernst, and Matsch discovered that their contract would not cover the price of recruiting models. So they engaged friends and family in their little business. The trio was tasked with decorating the new Burgtheater’s great stairs.

Sudden Turn Of The Event

At the end of 1892, tragic things happened in Gustav Klimt’s life. His father, Ernst Klimt Sr., and his younger brother Ernst had both passed away, the latter fairly unexpectedly from pericarditis. These tragedies deeply saddened Gustav. Additionally, he also became a provider for his sister and mother. Additionally, he had to take care of the widow and his dead brother’s daughter.

Klimt became a regular visitor to the residence of Helene Flöge. There, the widow of his brother lived. They had only been married for 15 months at her death. Emilie Flöge, the sister of Helene, and Klimt soon developed a close bond that would last the rest of his life and serve as the inspiration for his well-known portraits.

After the passing of his father and sibling, Gustav Klimt’s output halted. By that time, Klimt had started questioning and criticizing the painting methods of academic paintings. This resulted in a quarrel between Klimt and Matsch. A Ministry of Education advisory committee approached Matsch in 1893 to request help in designing the ceiling for the University of Vienna’s freshly constructed Great Hall. Whether at Matsch’s or the Ministry’s request, Klimt finally joined the project, although this would be their final working relationship.

For the university’s Great Hall, Gustav Klimt was commissioned to create three substantial ceiling paintings, including Philosophy (1897–98), Medicine (1900–01), and Jurisprudence (1899-1907). To the astonishment of his patrons, Klimt opted for these works to use a highly ornamental symbolism that is hard to interpret. All these new paintings and creations signaled a dramatic shift in his perspective on painting and art.

The nudity of some of the characters in Gustav Klimt’s paintings of universities and claims that they were ambiguous caused significant debate. After the uproar, Klimt vowed never again to accept a public commission. An interesting fact is that those paintings did not get installed at all.

GUSTAV KLIMT AND EMILIE FLÖGE

Vienna Secession

Gustav Klimt’s paintings for the University of Vienna took place simultaneously as a more significant division within the Vienna art scene and community. He decided to give up membership in Vienna’s premier society of artists, the Kunstlerhaus. He has been a member of this society since 1891. This event happened in 1891, and several prominent contemporary painters and designers also left this community.

Klimt and his fellow modernists stated they were denied the same rights to exhibit work there. This was because Kunstlerhaus preferred the better-selling conservative works. The Kunstlerhaus acted as the primary venue for exhibiting contemporary art in the city.

In order to create the Vienna Secession, which is also known as the Union of Austrian Artists, a group of modernist painters came together. This happened in 1897. The group also featured Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, Joseph Maria Olbrich, and Gustav Klimt.

Klimt was chosen to serve as the Secession’s first president. Its founding principles were to expose Vienna to foreign artists’ great works and give young and unconventional artists a venue to exhibit their work. Additionally, the Vienna Secession published a periodical, eventually named Ver Sacrum (“**Sacred Spring**“), which took its name from the Roman custom of cities sending younger generations of their citizens out on their own to found new settlements.

Through a number of shows, the Secession swiftly became a recognized force in the city’s creative community, with Gustav Klimt playing a significant organizing role. Numerous of them included pieces created by modern international artists who were accepted as corresponding group members.

Back then, the Viennese had little to no exposure to modern art; the shows drew widespread popular acclaim and minimal controversy. The Secessionists hosted their 14th exhibition in 1902 to celebrate the musician Ludwig Van Beethoven. Gustav Klimt created his renowned Beethoven frieze for this event, a large and intricate piece that curiously did not directly allude to any of Beethoven’s works. In its place, it was seen as a sophisticated, poetic, and extremely intricate metaphor of the creator as God.

The Secession was committed to the concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk. This is pretty much having a harmonious environment and attempting to be above the realm of commercial concerns. However, all those things seemed to be problematic for the members.

Two of its notable members, Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, established a new group called the Wiener Werkstätte in 1903, intending to promote and create ornamental arts and architecture for such uses. Hoffmann and Moser were close friends, and Klimt would later work with them on a number of Werkstatte projects, including the largest Gesamtkunstwerk created by the Werkstatte. This project was a “tree of life” created for Palais Stoclet in Brussels and was a multi-paneled piece.

Due to a disagreement about the group’s use of regional galleries, which were not particularly strong in Vienna, to sell their artwork, Gustav Klimt and a number of his companions left the Vienna Secession in 1905. The Secessionists had their own display space, but they were still plagued by the absence of an organized place to finalize the sale of their artwork.

The Klimtgruppe’s resignation stripped the Secession of its most well-known international contributors, but in the years since, it has undergone numerous self-reinventions, frequently accompanied by changes in leadership. As a result, it continues to be the only artist-run organization in Austria devoted to the promotion of contemporary art.

Final Years & Death Of Gustav Klimt

Klimt’s unique style, which intricately incorporated aspects from both the pre-modern and modern eras, fully developed between 1898 and 1908 while he served on commissions for the University and as a member of the Secession.

These works of art include The Kiss, Field of Poppies, Pallas Athene, Judith, and Adele Bloch–Bauer I. Despite the attention they now get, their response at the time was not always favorable: one critic joked that Bloch-Bauer I was “_more blech than Bloch_” when they first saw it.

Many of Klimt’s spectacular (but sometimes underrated) en plein air landscape paintings, including The Park, were created during these summer months. He was frequently seen being in the vintage points of beautiful, open fields or rowboats. Klimt’s two great passions were painting and women, and he seemed to have an endless desire for both.

Gustav Klimt made a point of keeping his personal affairs private. As a result, his personal life has been a well-known source of much discussion among critics and historians, particularly in light of Klimt’s women portraits. Numerous publications swear by Klimt’s personal liaisons. On the other hand, some publications question whether there was any romantic link between Klimt and the women shown in his art.

Even though Klimt didn’t change his subjects during his later years, his painting style underwent a lot of development. The artist started using delicate color mixtures, such as lilac, coral, salmon, and yellow, and largely abandoned the use of gold and silver leaf and ornamentation in general.

During this period, Gustav Klimt also created an astounding quantity of sketches and studies, the bulk of which featured naked women, some of which were so pornographic that they are still rarely seen today. However, several of Klimt’s paintings have received accolades for the artist’s increased focus on character and purportedly renewed attention to resemblance.

These characteristics may be seen in the works Adele Bloch-Bauer II, Mada Primavesi, and the oddly erotic The Friends, which shows what looks to be a lesbian couple, one naked and the other dressed against a stylized background of birds and flowers.

Most Famous Pieces of Art by Gustav Klimt

“The Kiss”

The Kiss is likely Gustav Klimt’s most well-known and overtly celebratory piece of romantic intercourse and his most frequently copied piece of art. It is often regarded as an outstanding example of Art Nouveau painting. Despite the composition’s general simplicity, the piece is a synthesis and a source of unique techniques.

Klimt’s topic is straightforward. He shows a couple cuddling close on the edge of a meadow, as suggested by the beautiful, yellow flower-like pattern underneath. The way the piece was put together demonstrates a thorough understanding of the Arts and Crafts movement. For instance, the people’s clothes and the flattened patterning of the field are reminiscent of late-19th-century William Morris textiles. Klimt’s use of fine materials, especially gold and silver leaf, highlights the work’s value and indicates a high level of specialized craftsmanship for its application to canvas.

The source material for Klimt, however, is far more intricate. Gustav Klimt utilizes golden and silver colors to emphasize the sacredness of human connections and the tie between sensuous lovers. As the crucial idea underpinning much of Art Nouveau, Morris and medieval sources employed such priceless materials to glorify literary subject matter.

Klimt broadens the idea of The Kiss’s appeal by allowing it to reflect a universal, eternal picture of passionate love. This leaves the characters unclear and therefore leaves behind their situational and personal importance.

THE KISS

“Adele Bloch–Bauer I”

This piece, which many people believe to be Gustav Klimt’s best creations, also happens to be one of the most well-known due to its pivotal involvement in one of the most infamous instances of Nazi art theft. Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of an Austrian banker and sugar tycoon, was one of the numerous ladies Klimt painted from life. She sat for two portraits and served as the subject for several other works, including his well-known Judith I.

Klimt was said to have been romantically engaged with several of the ladies he painted. Due to his extraordinary caution, academics still disagree over the precise nature of his connection with Adele Bloch-Bauer.

Even though Klimt shows Bloch-Bauer seated, it is quite difficult to make out the shape of the chair or distinguish her attire from the background. At this point, Klimt was primarily bothered with capturing the personality of his sitter, much less so with describing the setting and context.

Gustav Klimt employed several gold designs and tones in his paintings to produce these brilliant effects. Unsurprisingly, the picture was renamed The Lady in Gold when the Osterreichische Galerie Belvedere acquired it.

Klimt’s art draws on a number of earlier origins, despite his transition to contemporary abstraction. The Byzantine mosaics at Ravenna, Italy’s Basilica of San Vitale, which Klimt saw in December 1903, are the most notable. Klimt based Adele Bloch-portrayal Bauer’s portraits of her necklace on these mosaics. The whorls, coils, and other ornamental elements based on Bloch-initials Bauer’s may recall patterns from ancient Mycenae and classical Greece.

ADELE BLOCH-BAUER

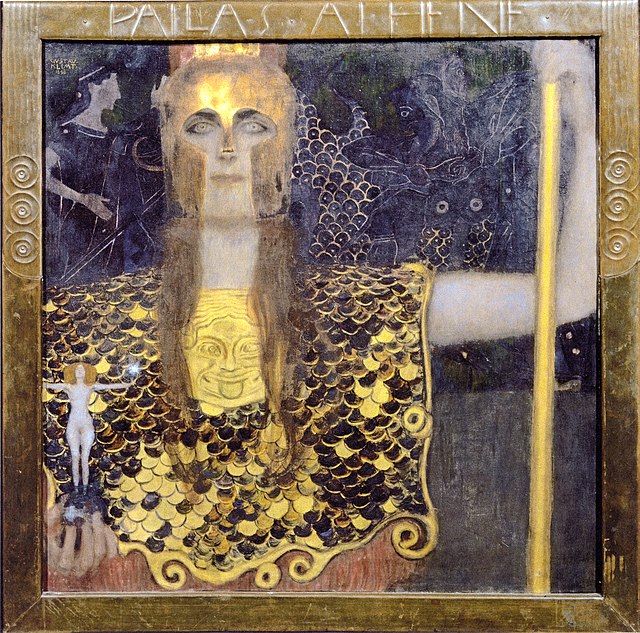

“Pallas Athene”

Klimt had a profound awareness of the symbolic aspects of legendary and allegorical characters and storylines from Greece, Rome, and other ancient civilizations, much like many of his contemporaries who painted and created graphics. Gustav Klimt starts the collapse of the figural in the direction of abstraction with his soft hues and hazy boundaries between elements.

Thus, rather than providing a clear, concise visual summary of the character of the Greco-Roman goddess of knowledge,this picture conveys a sensory idea of her imperial, overpowering presence. It all brings forward humans’ incapacity to fully comprehend that.

Importantly, Gustav Klimt is able to underline the goddess’ androgynous nature and muddled gender identity. This is made possible by the image’s fuzzy aspect. She is clad in military attire that signifies her status as a warrior and the defender of her hometown of Athens, traits that are often associated with men. Her femininity is only hinted at by the wispy hair strands that delicately hang down. She is holding the naked figure of Nike, who stands for triumph and is barely visible.

The haziness reminds one of Sigmund Freud’s contemporaneous study of dreams. It is tempting to interpret Klimt’s picture in light of Freud’s theory that dreams are the realization of desires. This may imply that the strong, imperious lady is the target of masculine desire but also that the conventional feminine identity must be dressed in order to achieve such status.

PALLAS ATHENE

Bottom Line

Gustav Klimt had a stroke on January 11, 1918, leaving his right side paralyzed. He developed depression when confined to a bed and could not paint or even draw, leading to his illness.

Gustav Klimt passed away on February 6th, becoming one of the pandemic’s victims. He was just one of four notable Vienna painters to pass away that year, the others being Otto Wagner, Koloman Moser, and Egon Schiele, the latter of whom also fell prey to influenza.

By his death, several modern art movements had attracted the interest of creative Europeans, including Dada, Dadaism, Cubism, and Constructivism. By that time, Gustav Klimt’s work was seen as representative of a bygone period in painting, which continued to emphasize human and natural aspects.