The Drop City Newsletter Archive | John Curl (original) (raw)

1966-1967

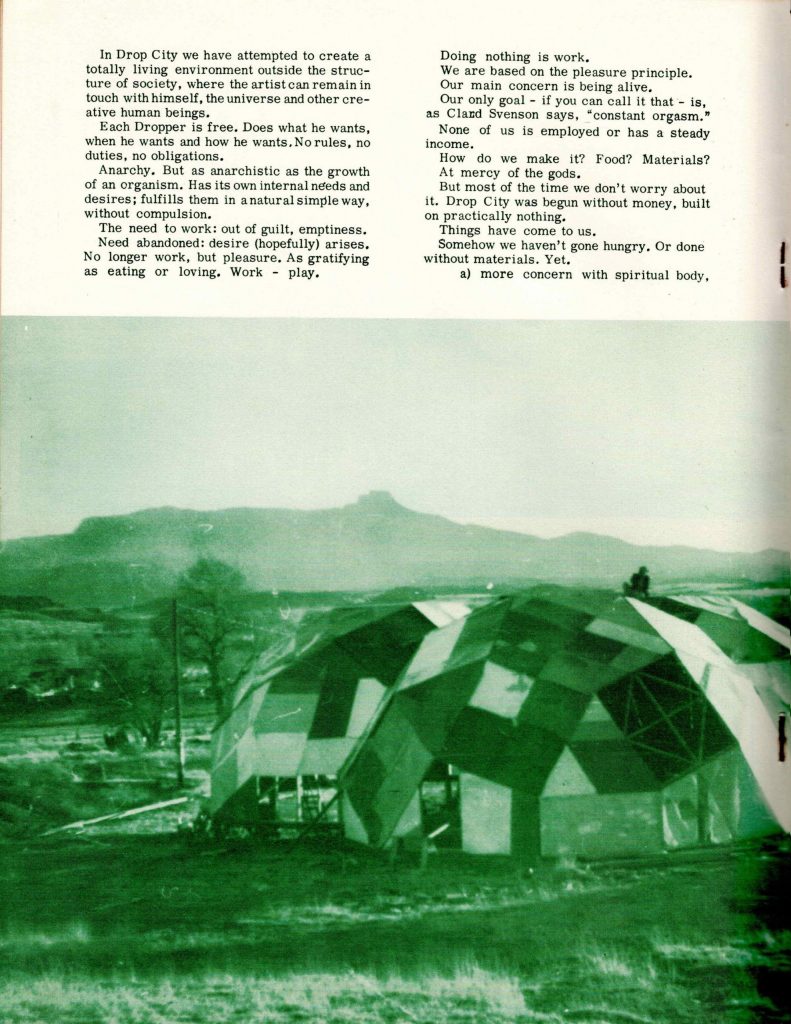

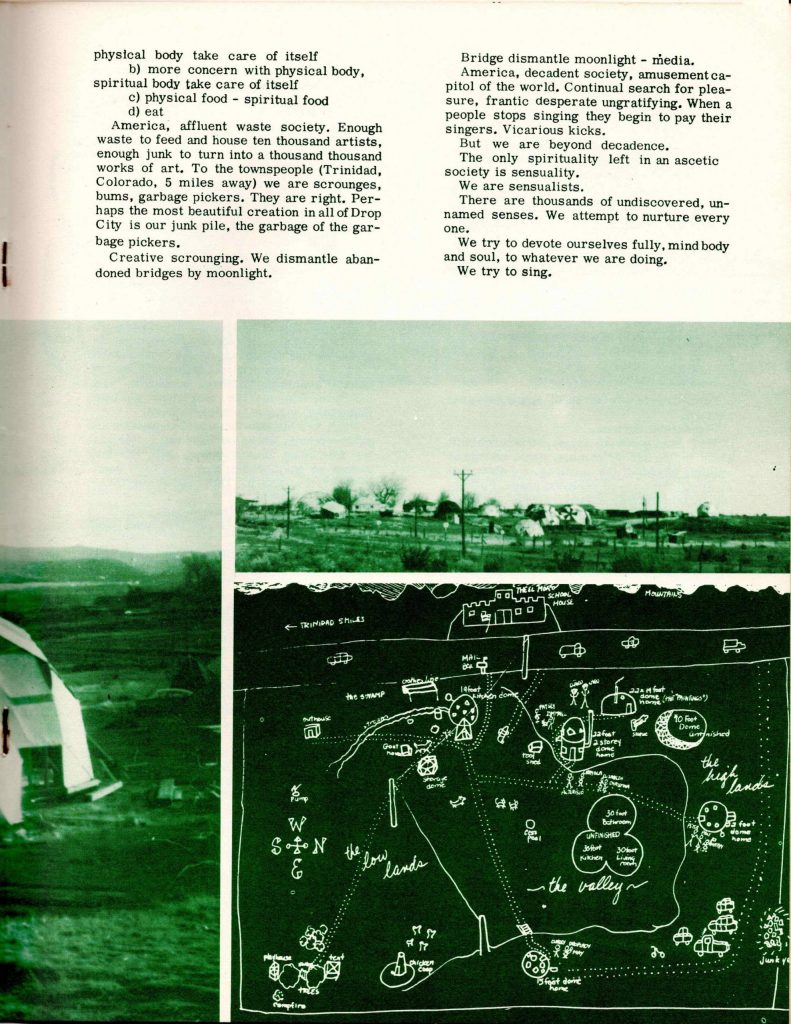

Drop City started out as an artist colony in 1965 near Trinidad, Colorado, and at the same time as a social experiment in living the Revolution, then quickly became the first hippie commune of the 1960s, the original countercultural community to use domes as housing, the prototype for the social movement that it helped touch off.

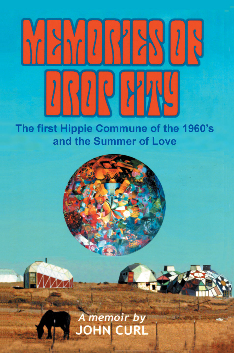

I arrived at Drop City in the spring of 1966, when the population totaled six adults and two kids, and I lived there for over two and a half years. I tell much of the story of the community’s rise and fall in my memoir, Memories of Drop City. Most of what I relate there is just as it happened, but those were legendary years in American history, with the social fabric in a great upheaval, and it almost felt like we were living there on a cusp between fact and fiction, so it felt fitting to use some fiction techniques to convey facts.

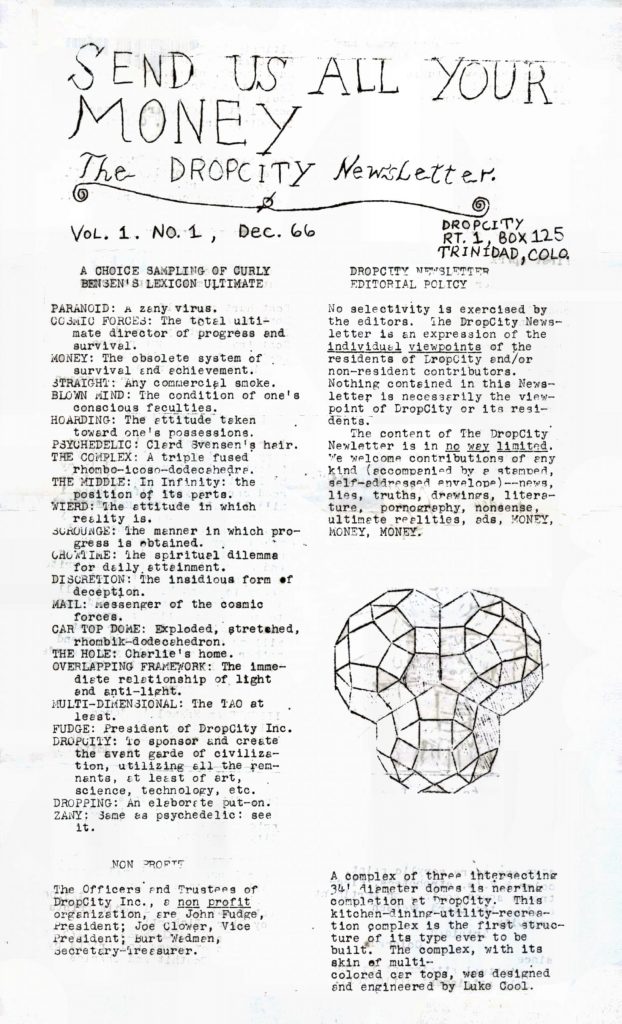

In our first Newsletter (1967), Curly Benson (aka Gene Bernofsky), one of the founders, defines the community as a verb: “DropCity: To sponsor and create the avant garde of civilization, utilizing all the remnants, at least of art, science, technology, etc.”

Drop City was always more than an artist colony: Gene, Joann, Clark, and Rich started Drop City on the premise that it was also an experiment in living, based on the idea that anybody could live there. The earth belongs to everyone, so everyone has the natural right to live on the land. All people are creative, but that is stifled by the constraints of this society based on individualism and exclusion, so when those constraints are loosened, everyone can be an artist.

Drop City as an experiment tried to provide the space in which the natural creativity of people could blossom, and tested whether people are even capable of creating a society based on sharing and cooperation, or whether greed, hording, and domination are too hardwired into our species. We had no formal leaders, and the main power was force of personality.

How could a herd of communistic hippie artists survive in rural Colorado, surrounded by heartland middle America? We installed art works all around the land, and they protected us. We made friends with the locals, who were mostly great people.

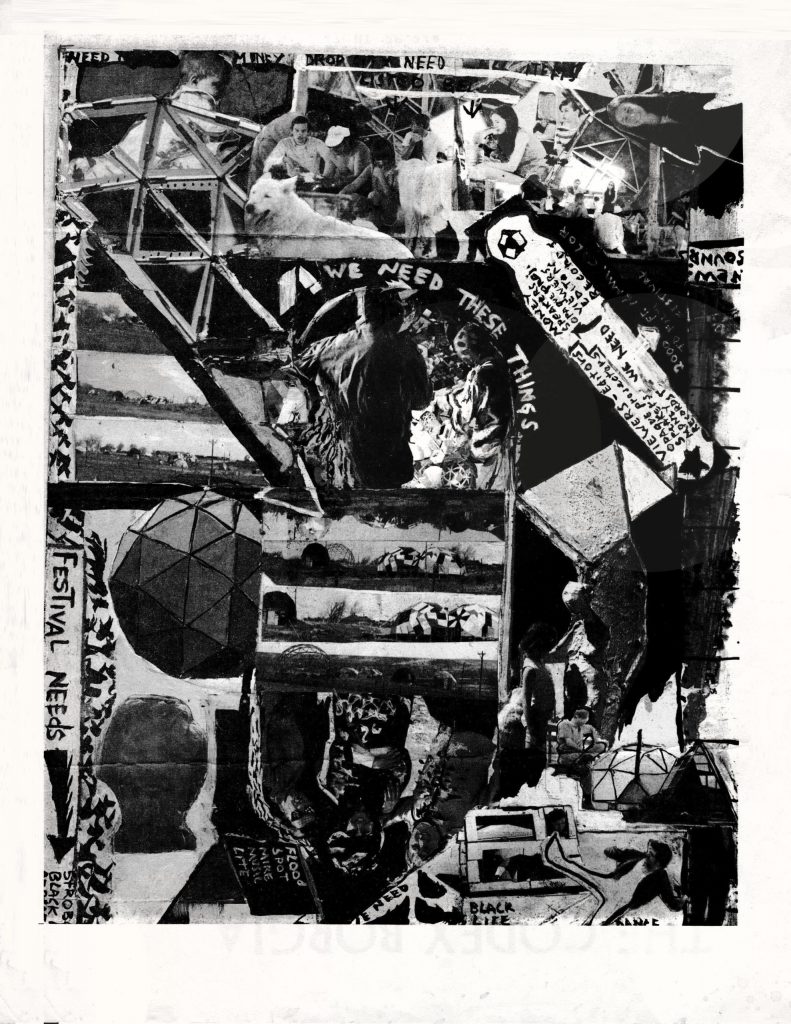

When someone gave us an old mimeo machine in the fall of 1966, we started publishing the Newsletter. Its purpose was to get the word out and to raise funds, the 1960s version of crowdsourcing. Our editorial policy was no selectivity, so the newsletter reveals the different unfiltered voices that were there. The headline of the first issue, Send Us All Your Money, was meant as a satire on ourselves. Drop City’s style was always humorous, because we wanted the Revolution to be fun.

This is the entire series of the Drop City Newsletters, which we published in 1966-1967. Over a half century later, the Newsletters offer a direct intimate glimpse into the lost world of the Droppers.

Drop City received the 1966 Dymaxion Award from R. Buckminster Fuller. The Ultimate Painting, a group work conceived by Clark Richert and Richard Kallweit, a spinning disk illuminated by strobe, in which I painted a small section, was exhibited in the Brooklyn Museum, then disappeared from somebody’s garage. We were also involved in early solar power when Steve Baer (inventor of the zome) and I built a solar heater that he designed for my dome in 1968. It stored the heat in rocks we scrounged from the nearby Purgatory river and worked pretty well. Steve published our communications about it in a broadside called Sol Shot, which I am including in this archive.

The post office refused to deliver the first issue of our newsletter, claiming that the cartoon on page 2 was obscene. After a few days they backed off and delivered them, but warned us to clean up or they would seize them next time. In the following issue you can read how a federal agent harassed us and spread rumors that we were dealing drugs, which was not true. The “drop” in Drop City was usually assumed to mean drop acid and drop out, but it also referred to a “dropping”, which meant a kind of interactive art prank. However, Timothy Leary did drop in for a visit.

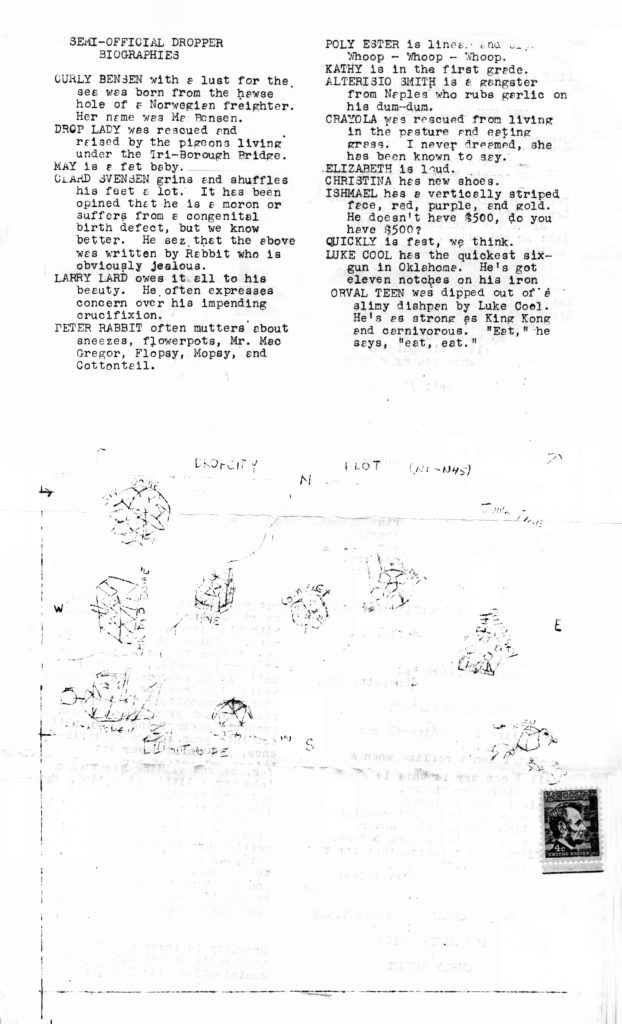

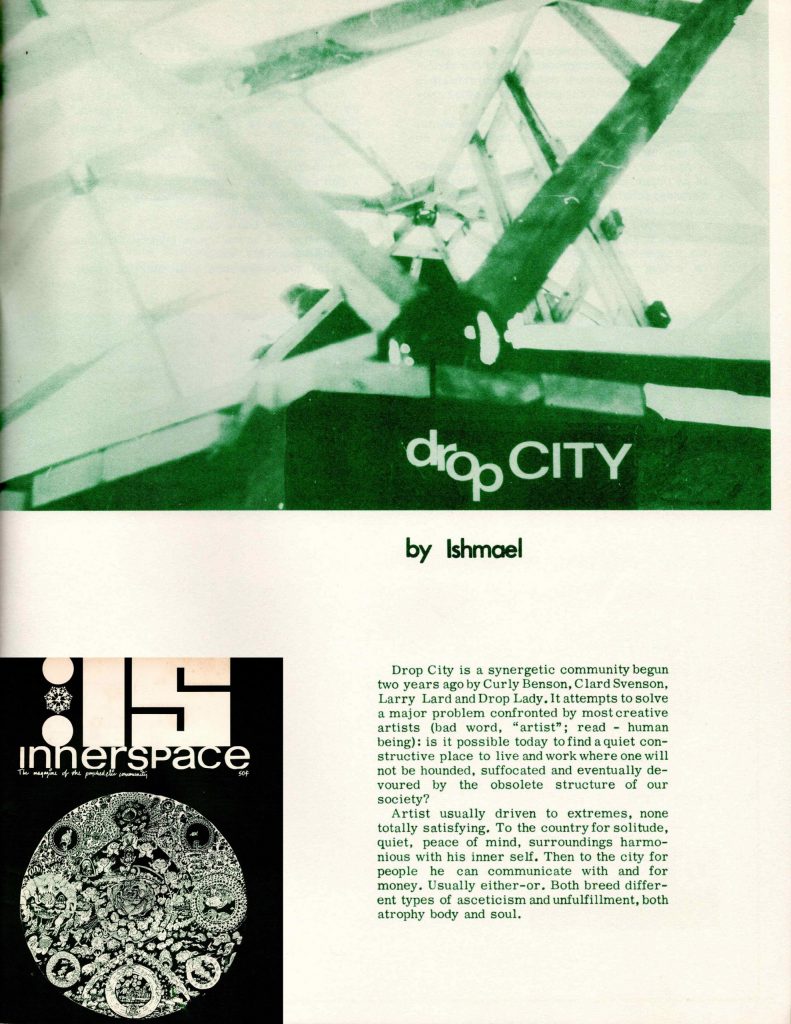

In the Newsletters, we all used our Dropper names. Gene was Curly, Joann Bernofsky was Drop Lady, Clark Richert was Clard Svenson, Richard Kallweit was Larry Lard, Charlie DiJulio was Alterseio Smith, Peter Douthit was Peter Rabbet, Jill Speed was Quickly, Steve Baer (who actually never lived there) was Luke Cool. My Dropper name was Ishmael. That was my first nom de plume or nom de guerre, and while I was at Drop City, I published a number of articles and short stories under that moniker, including an article I wrote about Drop City in 1967 for Inner Space magazine, which I am including here. I also published my first poetry chapbook, Change/Tears, in 1967 at Drop City under that name and on that same mimeo. You can download a copy of that poetry chapbook here. A few years later, in California, I started using a different alias, and called myself NJ when I was tagging poems on walls.

my first chapbook

We did light shows and poetry readings with local garage bands, and in galleries and bookstores in Taos and Santa Fe. I read with poets Max Finstein, Jack Collom, Larry Goddell, and of course Peter Rabbet. A number of other Droppers were excellent artists, including Jalal Quinn and Michele Kelley. Artists Dean and Linda Fleming were regular visitors.

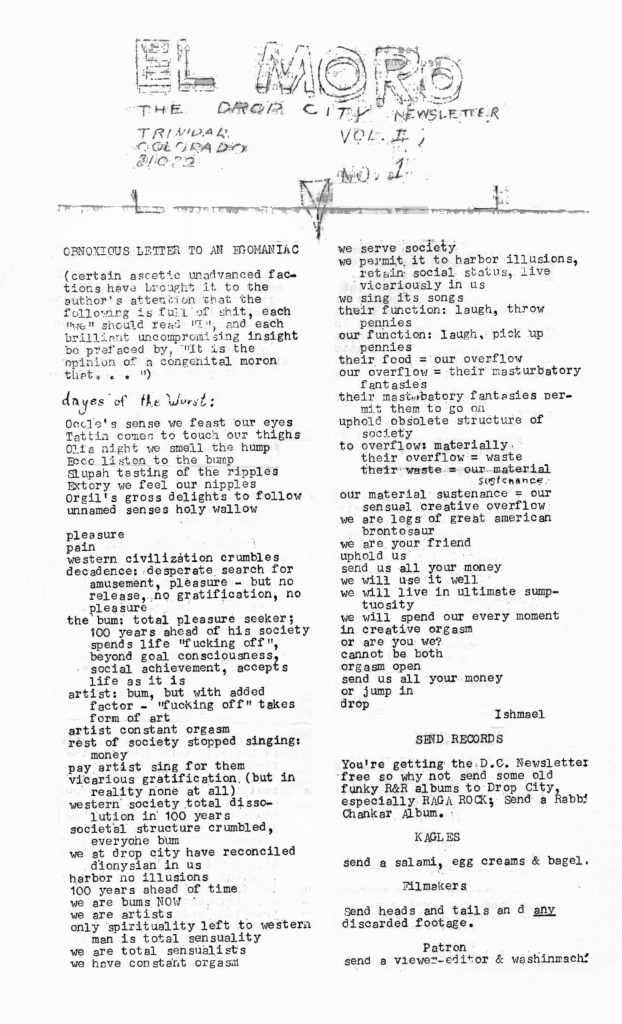

We were inconsistent with the numbering of the Newsletters, due to the vicissitudes of the collective process, artistic license, and maybe somebody was stoned. The masthead of the second Newsletter, El Moro, refers to the 19th century name given that land, because somebody thought that Fisher’s Peak looks like the old Spanish fort with that nickname in the harbor in Havana, Cuba.

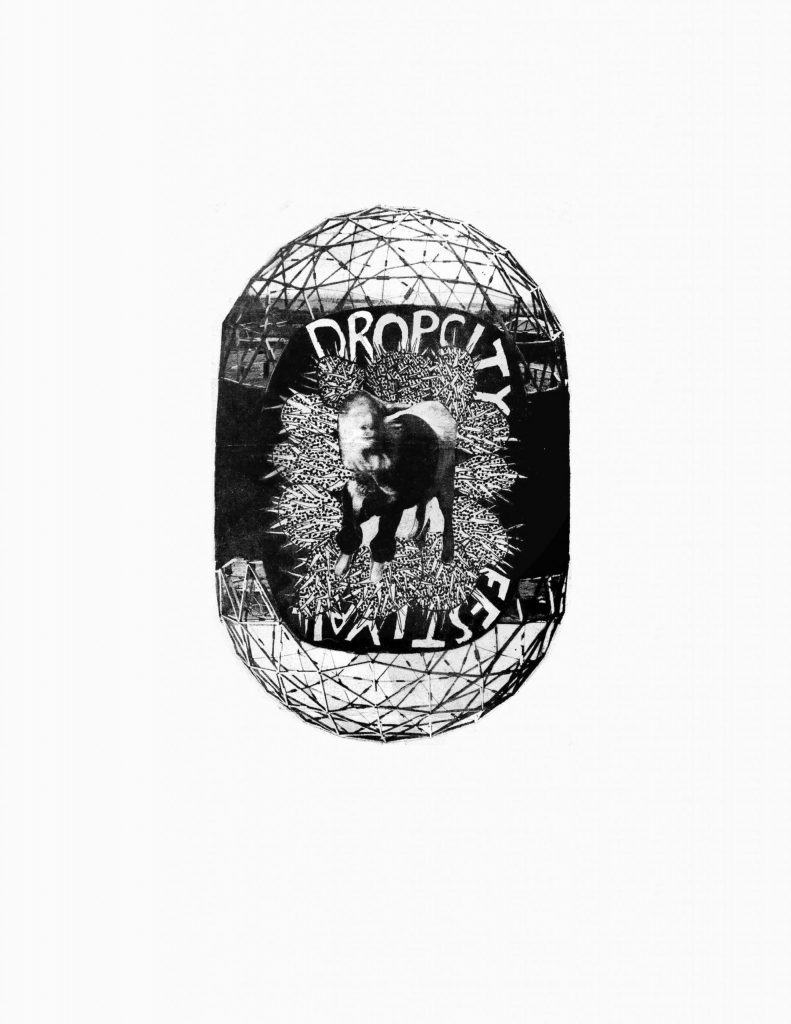

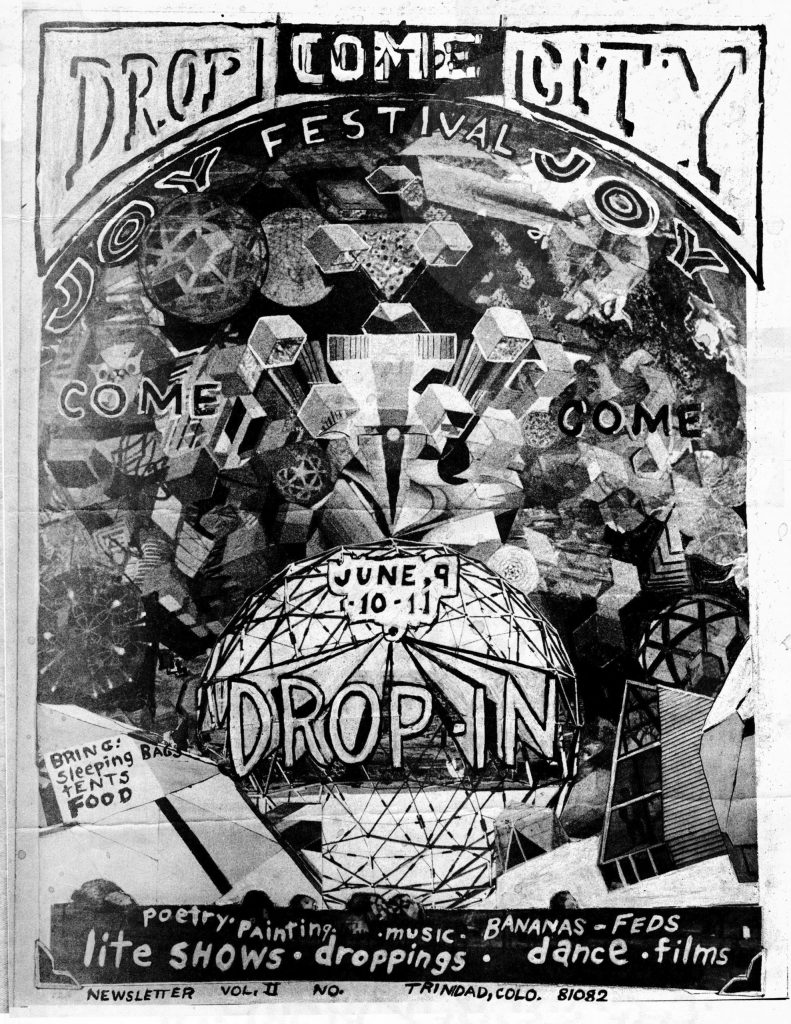

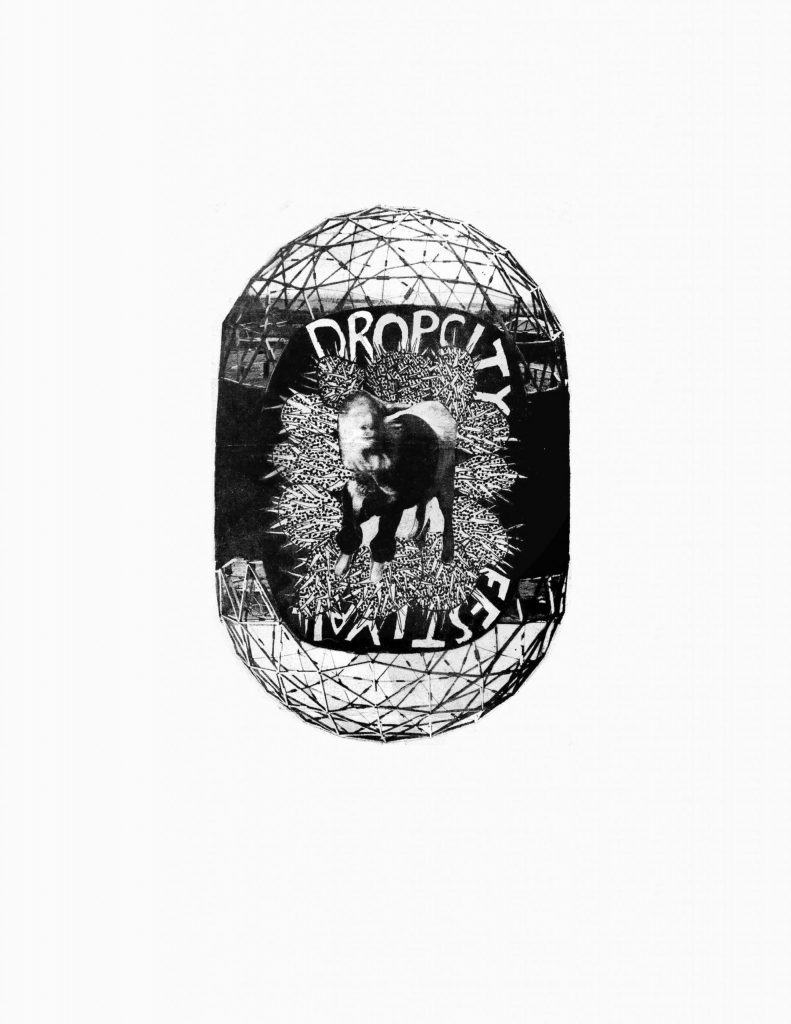

Our success brought attention in the national media, and our notoriety overwhelmed us. After the fourth issue, our Joy Festival brought an unending flood of people, which changed Drop City forever.

Obviously seven acres in the desert can hold just so many people without blowing all the fuses, so when things started to get out of hand, we set a population limit of fifty. However, no one can limit love, and the exception was that you could stay at Drop City if you hooked up with someone, so in effect there were no limits. With the hippie and communal movement exploding around us, with the Vietnam war and Western civilization destroying us, with a generation of young people set in motion, our population ballooned and ballooned again, and in the chaos things went south.

We never published another Newsletter. We only put out these four issues.

Drop City was a great experiment where I learned how to relate to others in an egalitarian group. I discovered a lot there about direct democracy, how people act in a liberated environment, and what happens to all the baggage we bring into it. I thought Drop City would be my permanent home, but that was not to be. Yet I would continue to work in collective and cooperative groups for the rest of my life.

My Memoir

My novelistic memoir of the 1960s and the hippie movement, Memories of Drop City, is available from the usual book sources. You can also DOWNLOAD FREE PDF COPY HERE

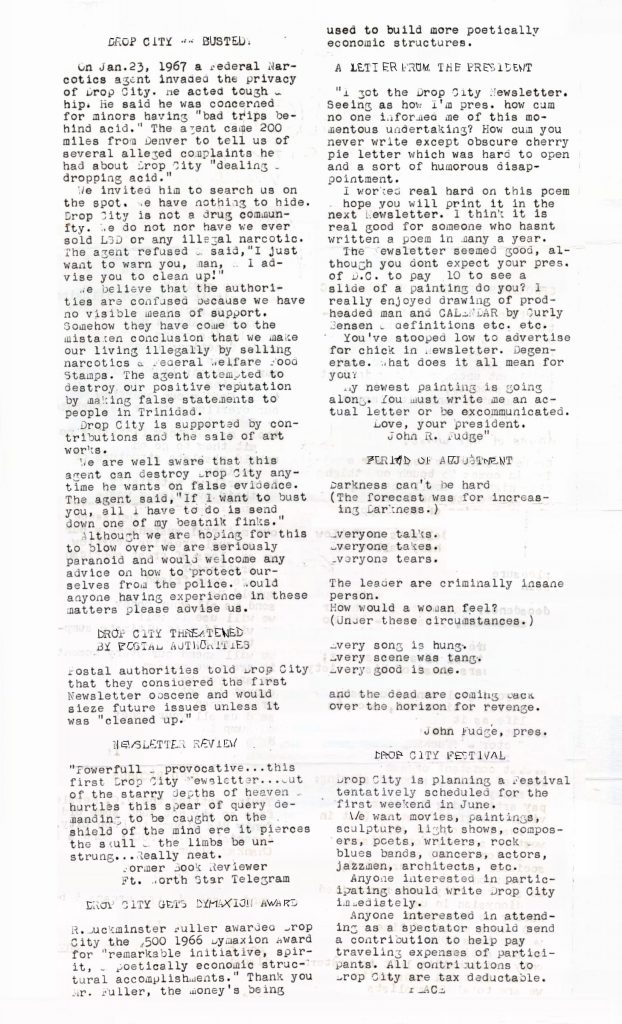

DC Newsletter 1- P.1

DC Newsletter 1- P.2

DC Newsletter 1- P.3

DC Newsletter 1- P.4

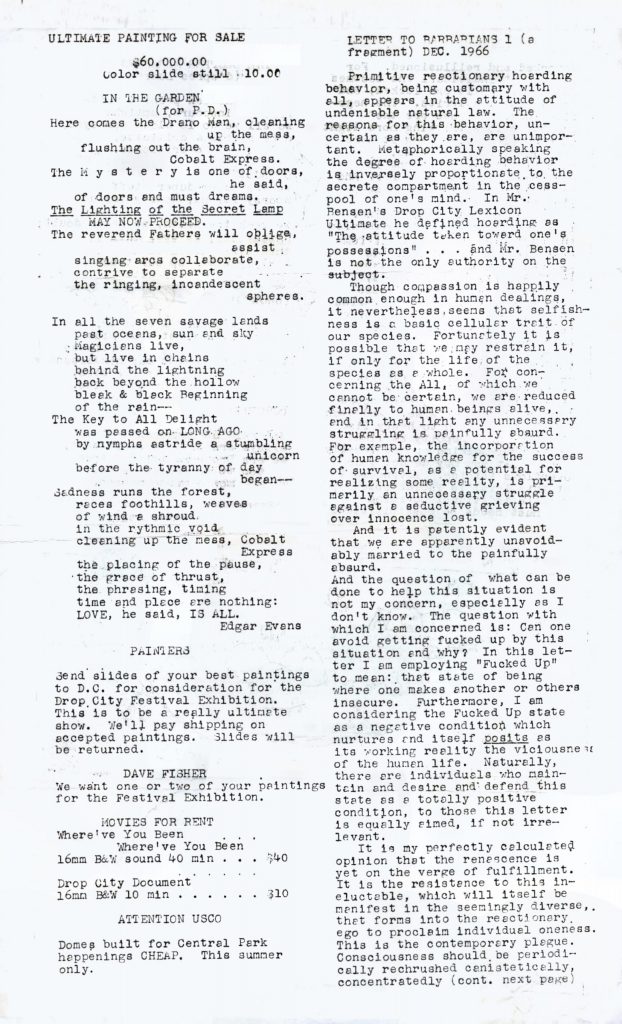

DC Newsletter 2- P.1

DC Newsletter 2- P.2

DC Newsletter 2- P.3

DC Newsletter 2- P.4

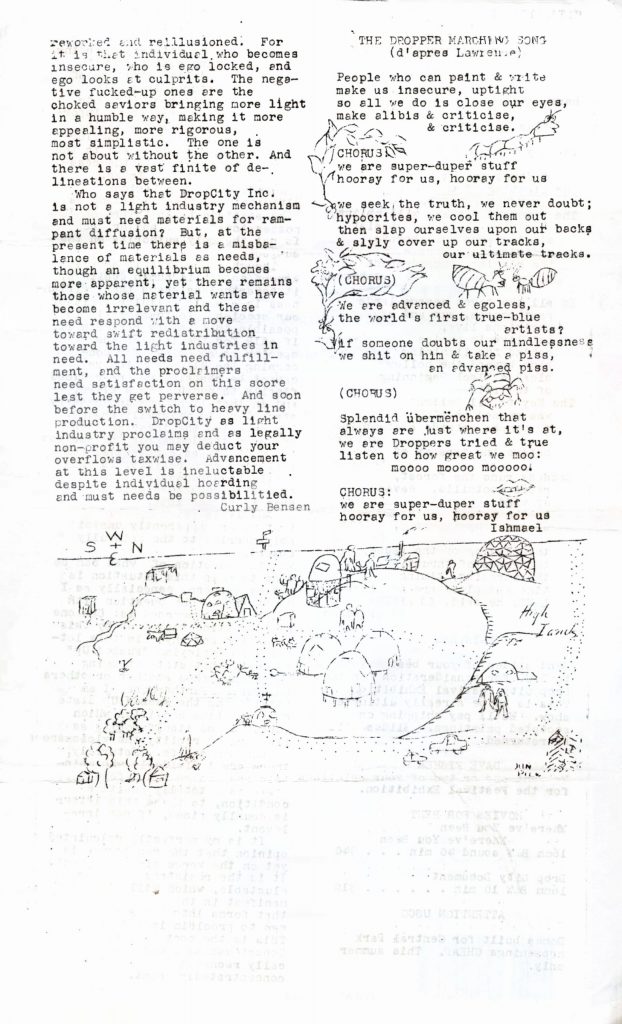

DC Newsletter 3- P.1

DC Newsletter 3- P.2

DC Newsletter 3- P.3

DC Newsletter 3- P.4

DC Newsletter 3- P.5

DC Newsletter 3- P.6

DC Newsletter 3- P.7

DC Newsletter 3- P.8

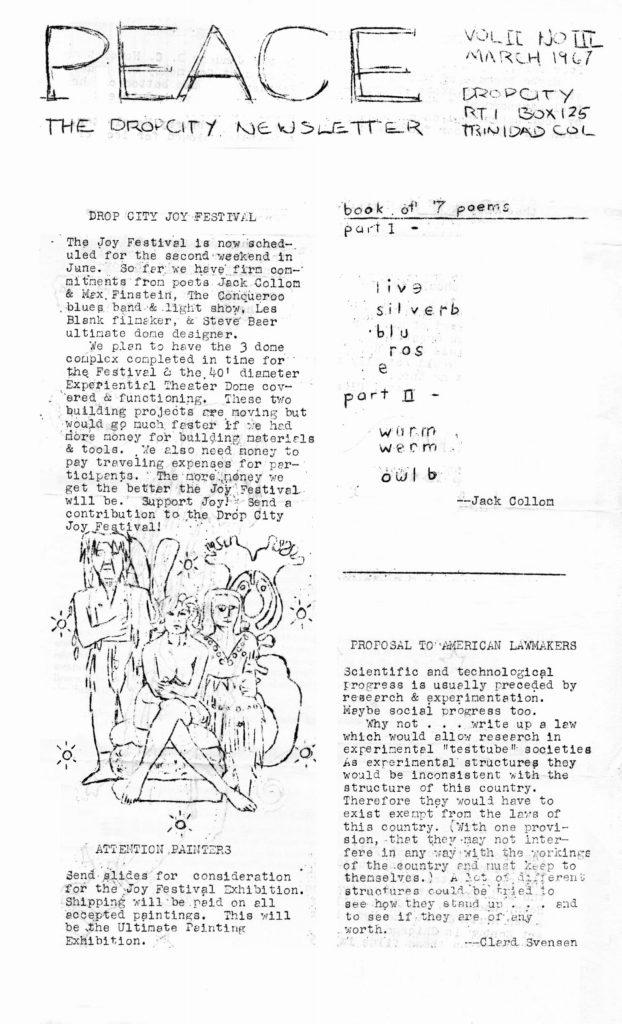

DC Newsletter 4- P.1

DC Newsletter 4- P.2

DC Newsletter 4- P.3

DC Newsletter 4- P.4

Inner Space Magazine, New York, 1967

Inner Space, P.2

Inner Space, P.3

Inner Space, P.4

Sol Shot Communications between Steve Baer and John Curl

The Solar Heater we built for my dome.

At my desk at Drop City, 1967

The Theater Dome