Emerson Buckley Interview with Bruce Duffie . . . . . (original) (raw)

[NOTE: This interview was recorded in 1986 and published in The Opera Journal in 1991.]

Conversation Piece:

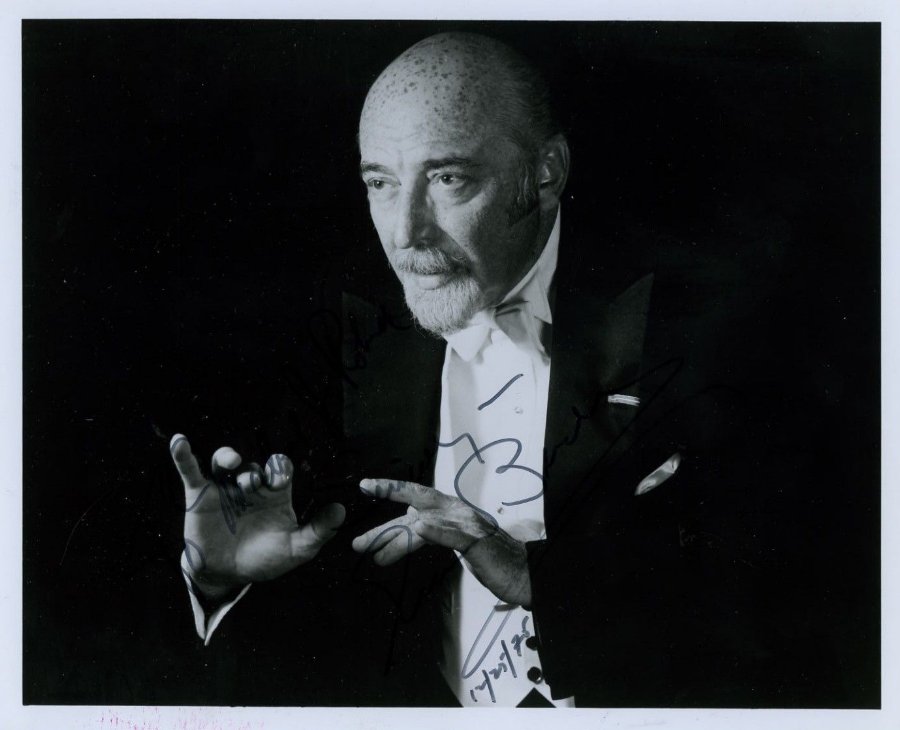

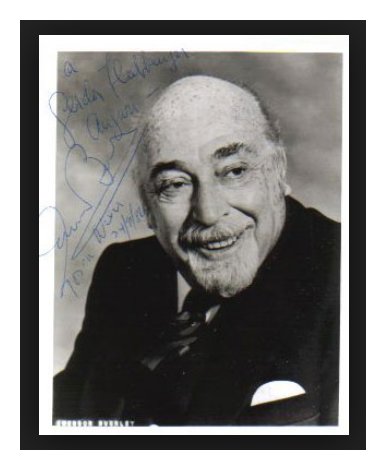

Conductor Emerson Buckley

By Bruce Duffie

This past April marked the 75th birthday-anniversary of the American conductor Emerson Buckley. Born in New York, he graduated from Columbia at the age of 20 and made his conducting debut that same year. During his remarkable career, he oversaw productions both large and small in America and abroad, and worked right up until his death in November of 1989.

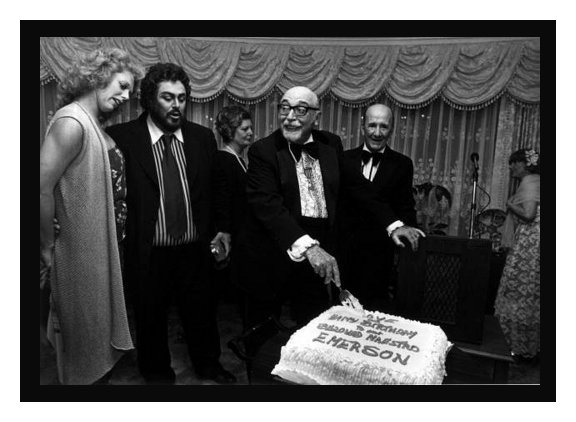

After 1950, his base was in Florida, where he ran the Opera Guild from 1950 to 1982, and the Ft. Lauderdale (later called the Philharmonic Orchestra of Florida) from 1963-86. He also was in charge of the musical side of the Central City Opera from 1956 to 1969, and the Seattle Opera from 1964-75. He made guest appearances in productions with the New York City Opera, and Lyric Opera of Chicago, plus countless others in both North and South America, Europe, and Asia including Beijing, China. He was also a favorite of Pavarotti and brought the assembled instrumentalists into shape quickly for many of the tenor’s crowd-pleasing concerts.

Just a few days after his 70th birthday, I caught up with Maestro Buckley while he was in Philadelphia. Business-like throughout the conversation, he pulled no punches when speaking about various operatic trends both good and bad, and had no illusions about himself.

Here is that conversation…..

Emerson Buckley

: I’m 50 years in the business.

Bruce Duffie: Let’s start right there… How has music changed in 50 years?

EB: It’s gotten so technological that I’m wondering if 10 years from now people will recognize a natural sound! People hear things in a room with speakers all around them, and then when they go to any of the great concert halls, they say, “Oh the sound comes from down there!”

BD: So is all the amplification equipment a mistake?

EB: No, it’s natural progress, but it should be used a bit more carefully than it is sometimes. I do these huge concerts with Luciano Pavarotti

– which are amplified – and I am glad that it’s bringing this type of music to more people than will fit in a smaller hall. We have special systems which make it as nearly-natural as possible in a hockey arena! We’ve been in Madison Square Garden, Maple Leaf Garden, the Forum, as well as various outdoor facilities.

BD: How do we get the public to understand that the live concert is not the same as what they get from a round-flat-plastic disc?

EB: That is very difficult to do if they hear the recording first. Concerts like Elisabeth Schumann gave in Town Hall aren’t being done anymore. Everything has to be bigger and better, so it’s mostly bigger and not always better. But there is a revival of chamber music these days.

BD: You’ve been working with voices for 50 years, how have they changed in that time?

EB: Their musicianship has come a long way. When I started out, even some very well-known singers did not read music at all, so any musical corrections had to be sung by me to them so they could learn it by rote. Nowadays, most of the kids are at least fairly decent musicians and have studied music.

EB: Their musicianship has come a long way. When I started out, even some very well-known singers did not read music at all, so any musical corrections had to be sung by me to them so they could learn it by rote. Nowadays, most of the kids are at least fairly decent musicians and have studied music.

BD: They’re better technicians, but are they better artists?

EB: [Pondering a moment] I don’t know because we are surfeited in mediocrity. This refers to vocalists, not instrumentalists. You have a very few greats, then a few pretty-goods, but to do opera all around the world you need a lot more to fill the roles.

BD: Are there perhaps too many singers trying to break into the business?

EB: In one way, that is true. They don’t wait for the complete training. Years ago they’d learn voice, then coaching and interpretation and language. They’d not have to go right out and sing when they weren’t ready. But who’s got the time today in a presto, presto world? They all have to make a living and the costs are so high. Marketing and publicity can do strange things, but that’s even more true in the pop field.

BD: Should we keep the pop and concert worlds separate?

EB: They’re bound to lap over into the one another back and forth, and some have been quite successful. Opera was the first multi-media art form, but now it’s so multi-media it isn’t funny. With all these things going on today, it’s difficult to say in what direction we’re heading. But it’s the same in science and even economics. I think it’s a phase we’re living in right now. It’s a period of turmoil and affects everything.

BD: Do the economic and scientific happenings affect your own musicianship?

EB: It affects your living. It affects your traveling tremendously. Last summer, I was in Bari doing a concert, and two days later I was rehearsing in San Diego. Last year I got a call in Florida on a Wednesday, and by putting another scheduled conductor in the performance, I did a Tosca on Friday in Vienna with no rehearsal. I’d worked with three of the singers, but to this day I don’t know who the rest of the cast was! I didn’t get a program. The principles were Pavarotti, Ingvar Wixell, and Ghena Dimitrova. They knew Tosca and I knew Tosca, but it’s not the ideal way to do an opera by any means. I had only enough time to meet with the stage director to check out when certain things happened onstage – Puccini writes so well for the stage

– then the chorus master for the backstage chorus, the assistant conductor who directed the offstage trio in Act II, and the prompter. That was it. We went on and it was quite a good show, too. Then I flew right back to Florida to finish what I was involved in there.

BD: Is it easier working with big, established stars than with young talent?

EB: I’ve found that the bigger they are, the easier they are. Nilsson was no trouble. Corelli no trouble. Tebaldi, Peters, Tucker, Bastianini, Vinay, the whole bunch. The greatest conductor’s singer I worked with was Margaret Matzenauer. You didn’t have to wait half a bar or a full bar for the new tempo – she was there. Martinelli, too. You could depend on these people. Giuseppe Taddei, who made his Metropolitan debut recently at age 69, was in an Otello with me in Puerto Rico. In the last act, we weren’t quite together for a moment, and I forgot to tell him about it after the performance. When I saw him the next night, before I said anything, he said, “Yes, Maestro, it was off last time, but it will be right tonight!”

BD: You’ve been involved in both old established operas as well as brand new ones. Where is opera going today?

EB: People say it’s a museum, but I don’t think that. It’s going to exist, but the old works don’t always have to be different. When you look at the same picture, you see the beauty of it. In opera, stage directors seem to think they always have to do something different, even if it doesn’t mean what they want to say, or what the music tells them. A lot of them just disregard the music.

BD: How much collaboration should there be between the director and the conductor?

EB: It should be director, conductor and designer. I had a wonderful experience in Central City, Colorado when Nat Merrill, Bob O’Hearn and I would get together on a new production. Each would discuss his point of view, and maybe the set would shift a bit so the chorus could be able to see. You work out the production that way with big ideas and small details. It is very difficult, though, just getting the people together. Another example is how many acts to play the work. Musically, you might want to go from one dramatic scene to the next for continuity, but the set needs to be constructed to facilitate that shift quickly.

BD: Are there some new operas being written that can stand alongside the old masterpieces?

EB: There are some very good ones coming along. Floyd’s works are good. Bob Ward’s are also good. [Note: To read my interview with Robert Ward, click here.] I’ve done two that I think will stand up: The Ballad of Baby Doe (by Douglas Moore), and The Crucible (by Robert Ward). I’ve done other premiers including Minutes till Midnight, He who gets Slapped (both also by Ward), and others.

BD: Did you know when you were doing the first performances of Baby Doe and Crucible that they would be substantial works?

BD: Did you know when you were doing the first performances of Baby Doe and Crucible that they would be substantial works?

EB: I felt they would be, yes. We put in a lot of work with the composer, conductor, stage director and scenic designer.

BD: How much alteration did the composer permit for you or the singers, or for simple expediency?

EB: He was sometimes easier than the librettist! It was funny, but I found that to be true. We tossed ideas back and forth. Cuts, also. In the original Baby Doe, there were three children’s games in the scene before Bryan comes on, and it was difficult to watch. Douglas Moore was willing to cut it, and Latouche was arguing about it. There was also a scene added after that first production.

BD: Did the public react to those performances immediately?

EB: Yes, they did. The Crucible won the Pulitzer Prize, and its four acts are like the four movements of a symphony. The music in the fourth act is all from the previous acts, developed and re-developed.

BD: What advice do you have for a young composer who wants to write an opera?

EB: To start with, watch your libretto. There must be conflict. A love interest helps, naturally. When you get people on and off stage, be sure you have enough music to do it. Eighty choristers cannot enter in four bars. In Beatrice and Benedict, Berlioz didn’t give enough music to get the chorus on.

BD: Are you optimistic about the future of opera?

EB: I think so, yes. Look at what’s happened with the regional companies in the last 20 years – there are many very good companies around now besides the big ones in New York, Chicago and San Francisco.

BD: What about choice of repertoire

– do the companies rely too heavily on the standard few?

EB: Well, the “standard few” has increased tremendously. When I was young, it was only a dozen or so. Now we have many more, and they’re from many different styles and languages.

BD: How do we get the public to be more accepting of brand new works?

EB: That is a tough job, and it depends on encouragement. Everyone wants to read the latest book and see the latest picture, so open your ears as well as your eyes. There has to be a general campaign on that, and it must include the critics. Instead of going out to “criticize” all the time, they could run an educational campaign by saying, “Go listen to this,” instead of writing comparisons all the time. Music wasn’t written for the critics. The composers had an inspiration of some kind and wanted to use their own forms of expression. That should be accepted by everybody, not just one person trying to make a rule.

BD: What do you expect of the public that comes to your performances?

EB: You can feel the reaction behind you. I feel it all the time. There is an excitement which is there if the performance is going well. Younger ones react more than the older ones do.

BD: Is that good?

EB: Yes, definitely. A sixth-grade student will accept newer music faster than a general-public audience. One of the greatest things for in-school performance would be The Nose by Shostakovich. They love things like that.

BD: Do you think opera works on television?

EB: Well, there are two different kinds of productions – those taken from stage performances, and those filmed in studios and on locations. Each presents different kinds of problems. When you do it like a regular film, you must combine the sound with the picture because you can’t get orchestra and singers recorded well in an open field, for instance. But television has done much to popularize opera.

BD: What about opera in translation?

EB: I’m fundamentally for opera in the original because the composer wrote it for that, but there are certain operas which work fine in the vernacular. Comic operas, if done well, usually work; they’re lost, otherwise. A conductor shouldn’t do an opera unless he knows the language well enough to know what’s going on all the time. I haven’t seen this new idea of supertitles, yet. If you know the opera very well, it can get in your way. For the general public, I imagine it’s a very good thing.

BD: I was wondering if the televised operas have paved the way for the translation in the theater?

EB: I think so.

BD: Are you pleased with the recordings you’ve made?

EB: Yes, definitely. They were made on budgeted time, too. Some of the hardest work I ever did was on those recordings of Baby Doe and Crucible. We had just so much time and that was it. We also had two tracks. Today you have 24 or more. But as long as you get a clear aural picture, you’re all right.

BD: At what point does the cut-and-paste become a fraud?

BD: At what point does the cut-and-paste become a fraud?

EB: That’s the whole trouble. As you know and I know, certain people never had certain notes consistently, so if they had them once in a while, you get them and piece them together to make one good one. Recordings must be monitored very well by good musicians, not just the technical staff. That’s part of what I meant at the beginning of our chat when I said things are becoming too technological. [Note: both times, the actual word Buckley used was “technicalogical.”]

BD: You won an award for French music…

EB: French opera was not being done at all, and John Brownlee, though Australian, was sort of brought up on French opera. So, as the President of the Manhattan School of Music, he and I decided to do a whole series of French works. We did Wertherbefore the Met or anyone else was doing it, we did Lakmé, Beatrice and Benedict, Mireille. The first big grant to the Manhattan school, which permitted them to move from the East Side to over by the Juilliard School, was on account of doing those French operas.

BD: Why is there the perception that French opera is so much more difficult to do?

EB: You have to get used to the style. Italian opera demands mainly on the voice; German operas are a combination of voice and dramatic ability, while the French has a style. The voice must be good, but to do that style you must master the language which has difficult vowels. Nowadays, we’re finally getting to hear them again so you can practically understand some of it.

BD: Practically???

EB: [Laughing] Practically. The women are the worst offenders. And it’s not just French. In Baby Doe, the

“Willow Song” always comes out “Oh wee-low.” It’s a singer thinking of a vocal sound.

BD: Is there any way to get the singers to work harder at their diction? [Note: Boris Goldovsky speaks at length on this subject in our interview which can be found here.]

EB: If they don’t have to do 45 performances and run back and forth between rehearsals, yes. So we’re back to the fundamentals of complete training. But some of the kids just don’t have the guts to go out there and do it. Lots of things get lost in the studio where they have the spoon feeding. At a certain time, that spoon feeding has to stop. On a piano, you punch down a key and sound comes out. Other instruments may be more difficult to produce sound, but in singing the body is the instrument. Singers must keep their bodies

– their instruments – in tune like athletes.

BD: A number of famous singers have told me that singing is like an athletic contest. Is that also true for conducting?

EB: [Laughing] Sometimes you might think so with some of the things we have to do. It’s a tough combination of moving and concentrating. Just try waving your arms for three hours without thinking about anything. Then you add the fundamental knowledge, plus the emotion. Your head has to be cold as ice even if your heart’s on fire.

BD: Same for a singer?

EB: Should be. You must approach notes carefully to keep the registers even and the scales precise.

BD: When you’re conducting, are you conscious of what the voice can and cannot do?

EB: I am, and each time I must make little adjustments for the particular person singing. You have to breathe with them. You breathe with instruments, too, but more with singers. You have to adjust all the time. Sometimes you get a live pit, sometimes a dead pit. Sometimes the orchestra is so crammed that it’s difficult to play. At Covent Garden, the large orchestras often spill into the side stage boxes because the pit isn’t big enough.

BD: Is all your work done in rehearsal, or do you leave a little bit for the night of performance?

EB: You do most at rehearsal – if you have a rehearsal! Youngsters often try things at rehearsal, and that’s fine, but I often tell them not to do that certain thing in performance yet. They need to wait until it’s secure and it will work. They’re playing with dynamite. They must be careful, but not overly careful so that they ruin phrases and break words. Sometimes they’re not conscious of their own capabilities. You ask for a certain phrase, and they reply that they haven’t got the breath for it. But they do have enough breath, and it works. Unfortunately, the old habit kicks back in later.

BD: So you need to form good habits in rehearsal.

EB: That’s right. Stage directors, also, must be careful about physical things that a singer can do. A smart director will work with the capabilities and limitations of the singers on hand.

Conversation Piece has been a regular feature in this magazine since 1985, and Bruce Duffie is looking forward to greeting those who have enjoyed these interviews at the convention this fall in Chicago. Next time in these pages, a chat with Verdi/Rossini scholar Phillip Gossett on his 50th birthday, and the following issue will present designer/director Robert Wilson as he reaches the same milestone.

Emerson Buckley, 73, An Opera Conductor

Published: November 20, 1989, in the New York Times [text only - photo added from another source]

Published: November 20, 1989, in the New York Times [text only - photo added from another source]

Emerson Buckley, a former artistic director of the Greater Miami Opera and the tenor Luciano Pavarotti's conductor, died of emphysema at his home in Miami on Saturday. He was 73 years old.

Mr. Buckley was the musical director of the Miami opera from 1950 to 1973 and later became its artistic director and resident conductor.

After retiring in 1986 from the Miami opera and as music director of the Fort Lauderdale Symphony, Mr. Buckley remained active. He was a guest conductor with various opera companies in the United States, China and throughout Europe. He spent much time during his last years touring as Mr. Pavarotti's conductor.

Mr. Buckley, a striking figure with silver hair and goatee, appeared in the 1982 feature film ''Yes, Giorgio,'' which starred Mr. Pavarotti as a pampered opera star. Mr. Buckley also appeared in ''A Distant Harmony,'' a documentary about Mr. Pavarotti.

A native of New York City, Mr. Buckley graduated from Columbia University in 1936. In the same year he obtained his first post, as conductor of the Columbia Grand Opera. For the next 10 years he held numerous positions in opera, ballet, symphony and broadcasting.

He is survived by his wife, Mary Henderson Buckley, a voice teacher; two sons, Robert, a theatrical producer and general manager in New York City, and Richard, of Ontario, Canada, a musical director.

© 1986 Bruce Duffie

This interview was recorded on the telephone on Arpil 16, 1986. This transcription was made in 1991 and published in The Opera Journal that June. It was slightly re-edited and posted on this website in January, 2009.

To see a full list (with links) of interviews which have been transcribed and posted on this website, click here.

Award- winning broadcaster Bruce Duffie was with WNIB, Classical 97 in Chicago from 1975 until its final moment as a classical station in February of 2001. His interviews have also appeared in various magazines and journals since 1980, and he now continues his broadcast series on WNUR-FM, as well as on Contemporary Classical Internet Radio.

You are invited to visit his websitefor more information about his work, including selected transcripts of other interviews, plus a full list of his guests. He would also like to call your attention to the photos and information about his grandfather, who was a pioneer in the automotive field more than a century ago. You may also send him E-Mailwith comments, questions and suggestions.