Springfield, Missouri – Queen City of the Ozarks – Legends of America (original) (raw)

Springfield, Missouri, located in the southwest part of the state, is the county seat of Greene County and the third-largest city in Missouri. Known as the “Queen City of the Ozarks” and the “Birthplace of Route 66,” it is rich in history, including Native Americans, Civil War Battles, and the development of the Mother Road.

Osage Indians by George Catlin.

Though the Delaware, Kickapoo, and Osage Indians had rights to the area, settlers began to filter into Greene County long before Missouri became a state in 1821. In 1830, the U.S. Government forced the removal of the Indians to a reservation in Kansas, and Greene County was opened for settlement, bringing in more pioneers to the new state of Missouri.

The county was officially established on January 2, 1833, and named for Revolutionary War hero Nathaniel Greene. Small settlements began to pop up all over the county in no time, such as Springfield, Brookline, Ash Grove, Republic, and Willard. Springfield, founded by John Polk Campbell, was the largest. Arriving from Tennessee in 1829, Campbell found a natural water well flowing into a small stream at the foot of a wooded hill. Wasting no time, he carved his initials into a tree, establishing his claim. Returning to Tennessee for his family, he returned in March 1830. The business district started with Junius Cambell’s store at Olive Street and Jefferson Avenue in 1831. Before long, other settlers arrived, and the area became a sizable log cabin settlement with several stores, mills, a school, a post office, and other businesses.

In 1835, the townsite was platted when John Campbell deeded 50 acres for the county seat. Two years later, a two-story brick structure was completed in the middle of the public square, serving as Springfield’s courthouse. In 1838, the town was officially incorporated.

In 1858, Springfield became a stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail stagecoach line, which ran from Tipton, Missouri, to San Francisco, California. This brought even more people to the area. By this time, the town supported some 1,200 residents and boasted three hotels, two newspapers, three churches, five schools, a bank, and several retail businesses.

Battle of Wilson Creek, Missouri.

However, a few years later, the Civil War would tear the prosperous city apart. Missouri was a bitterly divided state between Northern and Southern sympathizers, and the first battle of the area, The Battle of Wilson’s Creek, occurred some 12 miles southwest of Springfield on August 10, 1861. This battle was the first major Civil War engagement west of the Mississippi River, involving about 5,400 Union troops and 12,000 Confederate soldiers. The skirmish was also one of the bloodiest of the war, with over 1317 Union and 1230 Confederate casualties. Although a Confederate victory, the Southerners failed to capitalize on their success.

Two years later, on January 7-8, 1863, the city would become the scene of a Civil War conflict in what would become known as The Battle of Springfield. In an attack by Confederate General John Marmaduke, the Confederates attempted to capture the city of Springfield and its military stores. Though more than 100 men lost their lives, the attack was repulsed, and Springfield was spared from capture by the Confederate forces. Though many people left Springfield during this turbulence, many returned after the war and began rebuilding the city.

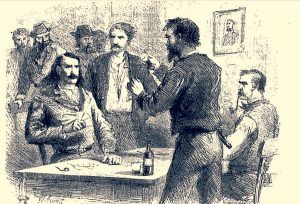

Bill Hickok and Tutt illustration from Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1867.

Though Springfield has never been considered one of the many notorious Wild West towns, it has one gunfighter legend. On July 21, 1865, famous gunfighter James “Wild Bill” Hickok killed an Arkansas man by Dave Tutt. Dueling in the streets, the dispute was prompted the night before when Tutt had won Hickok’s pocket watch in a poker game. Though Wild Bill was arrested, he was later acquitted of the murder.

The arrival of the St. Louis and San Francisco Railroad in 1870 further boosted the city’s economy. By 1878, over 150 business houses were operating in Springfield, which had become so popular that it became known as the Queen City of the Ozarks.

In 1880, a woolen mill produced 1500 yards of cloth daily, cotton mills converted 1,000 bales of cotton into fabrics annually, and mills ground 200 barrels of flour per day.

In 1887, Springfield was one of the first cities in the nation to get an electric trolley. The system quickly spread with lines going to many different parts of town, and riding the streetcar soon became not only a convenience but a form of entertainment. The last streetcar ran in 1937.

By the turn of the century, Springfield had about 23,000 residents.

John T. Woodruff.

By 1923, the city had 148 miles of streets, 60 of which were paved. So, when John T. Woodruff of Springfield and Cyrus Avery of Tulsa, Oklahoma, began to suggest a transcontinental highway, Springfield was a logical choice along the path of what would soon become Route 66. Woodruff and Avery worked tirelessly for a highway that would carry America’s new “Mobility Nobility” from Chicago, Illinois, to Los Angeles, California. Persistence prevailed, and Route 66 finally became a reality in 1926. Springfield became an important transportation hub, further aiding its population and economic growth.

John Thomas Woodruff was the Missouri partner promoting Route 66, an infallible businessman, and a promoter of all types of transportation throughout Missouri.

As an attorney for the Frisco Railroad in Springfield, he was largely responsible for developing other businesses in the burgeoning city, including the hospital, fairgrounds, and golf course. He also influenced the developments of Powersite, Norfork, and Bagnell Dams.

The Kentwood Hotel was built in 1926 by John T. Woodruff and is now a dormitory for MSU.

He also constructed the Woodruff business building, which still stands today, and the Sansone, Colonial, and Kentwood Arms hotels. Only the Kentwood Arms, built in 1926, remains. Today, Southwest Missouri State University owns the building, which is used as a dormitory called Kentwood Hall.

When Route 66 came through, motor courts, gas stations, diners, and cafes were built to service the many travelers. Billboards and neon once dotted the landscape.

A street in downtown Springfield, Missouri, by Kathy Alexander.

By 1940, the population of the city had reached over 60,000. Spurred by rapid industrial growth over the next 20 years, Springfield’s population increased dramatically, resulting in 100,000 by 1960.

Though Springfield is a modern city today, Route 66 once passed through its very heart. Like many cities that have seen immense growth since the advent of the Mother Road, you sometimes have to keep a sharp eye out to find evidence of the old highway.

There are two paths you can travel the route through Springfield, exit I-44 at Kearney Street and head west. Continue on Kearney St, and you will be on primary Route 66. However, City 66 begins at Glenstone, where you will turn south to St. Louis Street/College St. Continuing your journey, you will soon reach the town square, where you will veer to the right to get on College Street to the Chestnut Expressway, winding up on Missouri Highway 266.

Rest Haven Court Sign, Springfield, Missouri, by Kathy Alexander.

Your journey through Springfield will first take you past the site of the long-abandoned Sunset Drive-in Theater. Though the drive-in is long gone, the sign still stands. A bit further down the highway, you will see the remains of an old motor court on the north side, and a few miles beyond, the Rest Haven Court, at 2000 E. Kearney Street, one of the few original Route 66 motels left in Springfield today.

After a tour down Glenstone on City 66 and turning onto St. Louis St, you’re in for a treat. At 1158 E. St. Louis is one of the older Steak “n” Shakes from 1962, complete with shiny chrome and vintage sign. Steak ‘n’ Shake began on Route 66 in Normal, Illinois, back in 1934. However, this Springfield, Missouri, location is unique because it hasn’t changed much from its original design. From the building to the curb service window, they have kept the retro look throughout, and it’s said to be one of two surviving Steak ‘n’ Shake’s with the 50’s/60’s era design. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on August 1, 2012 (Read more on Route 66 News).

Downtown, are many old buildings, including the Woodruff Building and the historic Lander’s Theater, which is reportedly haunted. The Gillioz Theatre at 325 Park Central East opened on October 12, 1926, just one day after Route 66 was named. It was completely renovated in 2006.

As you travel west of the square on the old road, you will see the pristine Melinda Court, which continues to serve travelers of the Mother Road today. Another vintage motel – The Wishing Well Motor Inn is a bit further along the line.

Shamrock Motor Court, Springfield, Missouri, by Carol Highsmith.

Very few more vintage icons are left in a city that grew quickly after Route 66 was born and even faster when decommissioned. But still, Springfield was the home of Route 66 co-founder John T. Woodruff, making it a special place along the Mother Road.

Groundbreaking for a new Route 66 Roadside park was held in 2014. The park is on West College Street, between Fort and Broadway. It’s a tribute to Springfield’s designation as the Birthplace of Route 66.

Springfield’s population is about 168,000 today. Set in the pristine rolling hills of southwest Missouri, the city has many amenities to offer the visitor, including museums, nightlife, culture, history, and more.

Landers Theater in Springfield, Missouri by Kathy Alexander.

If you’re heading west on the Mother Road, continue on a ghost town stretch through Halltown, Paris Springs Junction, and Spencer for more peeks of the vintage road.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated October 2024.

Also See: