Images: One-of-a-Kind Places on Earth (original) (raw)

Unique Places

(Image credit: Matt Ragen, Shutterstock)

From the hottest deserts to the iciest mountains (like the slopes of Mount Rainier, above), the world is a many-splendored place. But some spots are one-of-a-kind, with sights that can't be seen anywhere else on the planet. Here, we list some of these amazing places. Let's go exploring.

Where the Clouds Roll By

(Image credit: Mick Petroff, distributed via a Creative Commons license.)

A rare tubular cloud formation occurs with regularity only one place on Earth: Northern Australia’s Gulf of Carpentaria. Here, ultra-long "roll clouds" form regularly in fall months. The phenomenon even has its own, geographically specific name, the Morning Glory cloud. Elsewhere in the world, roll clouds pop up only very occasionally, usually associated with sea winds or sometimes thunderstorm downdrafts. [See more images of curious clouds]

Where the Snow Is Like Knives

(Image credit: European Southern Observatory, distributed under a Creative Commons license.)

These sharp snow formations make the white stuff look uninviting. They’re called penitentes, and although they can form at high altitudes anywhere, there’s no place better to see them than in the Dry Andes of Chile and Argentina, way up past 13,000 feet (about 4,000 meters).

Penitentes, named after pointy hats worn by people doing penance for their sins in Christian traditions, form in very cold, dry air, where the water in snow sublimates, or turns directly into vapor without melting first. Sublimation randomly occurs faster in some areas than in others; once uneven pock-marks form in the snow, they focus the sunlight, causing those areas to sublimate ever faster. Spiky penitentes get left behind, unmelted. The tallest penitentes can reach 12 feet (4 meters) high.

Where the Lakes Explode

(Image credit: Jack Lockwood, 1986 (U.S. Geological Survey))

To see a lake that can kill you without you even dipping in a toe, visit Africa. In Cameroon and on the border of Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are three deadly lakes: Nyos, Monoun and Kivu. All three are crater lakes that sit above volcanic earth. Magma below the surface releases carbon dioxide into the lakes, resulting in a deep, carbon dioxide-rich layer right above the lakebed.

In 1984, Lake Monoun abruptly exploded, releasing waves of water and a cloud of carbon dioxide. Thirty-seven people who lived near the lake asphyxiated in the CO2 cloud, though the cause of their deaths remained a mystery until two years later, when Lake Nyos let out its own burst of carbon dioxide. This time, 1,700 people died when the carbon dioxide, which is heavier than oxygen, displaced the breathable air in their villages.

Venting pipes have been installed in Lake Nyos and Lake Monoun in an attempt to release the carbon dioxide gas slowly and prevent future disasters. Kivu, which has never erupted, is not being vented, although local companies do extract dissolved methane from the lake to use for power generation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Where Tsunamis Sweep Mountains

(Image credit: Hung Chung Chih, Shutterstock)

In landlocked Bhutan, tsunamis are becoming a danger. Climate change is melting Himalayan glaciers, increasing the risk that glacial melt will break through ice dams and wipe out villages. Scientists call these flash floods, one of which killed dozens in 1994, "glacial-lake-outburst floods," but in layman's terms, they're mountain tsunamis.

Bhutan is working to ease the danger by draining some high glacial lakes and shoring up their natural dams. Glacial lake outbursts can happen anywhere where glaciers are melting, but according to Bhutan's government and the United Nations, 24 of the country's 2,674 glacial lakes are at risk, making Bhutan the epicenter of this phenomenon. [Ice World: Gallery of Awe-Inspiring Glaciers]

Where the Rocks Walk

(Image credit: Lukich, Shutterstock)

At Racetrack Playa in Death Valley, it’s not horses or stock cars that make the rounds — it’s rocks. This pancake-flat dry lakebed is marked by tracks of large rocks that seem to have wandered from here to there under their own power.

In fact, the rocks (some of which weigh tens or hundreds of pounds) may require a perfect storm to get moving. According to lunar and planetary sciences researchers at NASA Goddard, wind pushes the rocks around. But for the wind to move huge boulders, there has to be little friction between the rock and the ground. Most likely, ice-encrusted rocks get inundated by meltwater from the hills above the playa, according to NASA researchers. When everything’s nice and slick, a stiff breeze kicks up, and whoosh, the rock is off.

Where Crystals Dwarf Humans

(Image credit: Screenshot from "El Misterio De Los Cristales Gigantes," by Javier Trueba, produced by Madrid Scientific Films.)

Imagine an underground world where shimmering crystals crisscross caverns like a giant’s Tinkertoys. Mexico's Cave of Crystals, buried below the Chihuahuan desert, is just that. Here, enormous crystals of selenite grow more than 30 feet (10 meters) long.

But this fantasy world is tough to withstand. The cave is nearly 1,000 feet (300 meters) below the surface, and a magma chamber below keeps the caverns heated to about 136 degrees Fahrenheit (58 degrees Celsius), with 99 percent humidity. Explorers must wear protective gear if they hope to survive in this crystal cave for more than a few minutes. [Amazing Caves: Pictures of the Earth's Innards]

Where Lightning Strikes Way More Than Twice

(Image credit: Thechemicalengineer, via a Creative Commons license.)

Clear skies rarely prevail at the mouth of the Catatumbo River in Venezuela. Here, it storms on average every other night, as moist, warm winds meet the nearby ridges of the Andes and explode into electrifying tempests. The lightning is so consistent that sailors have been known to navigate by its glow, which even reportedly saved the city of Maracaibo from attack by the English pirate Sir Francis Drake in 1595. According to a 1597 poem, the lightning illuminated Drake’s fleet, alerting the city to the pirate's presence.

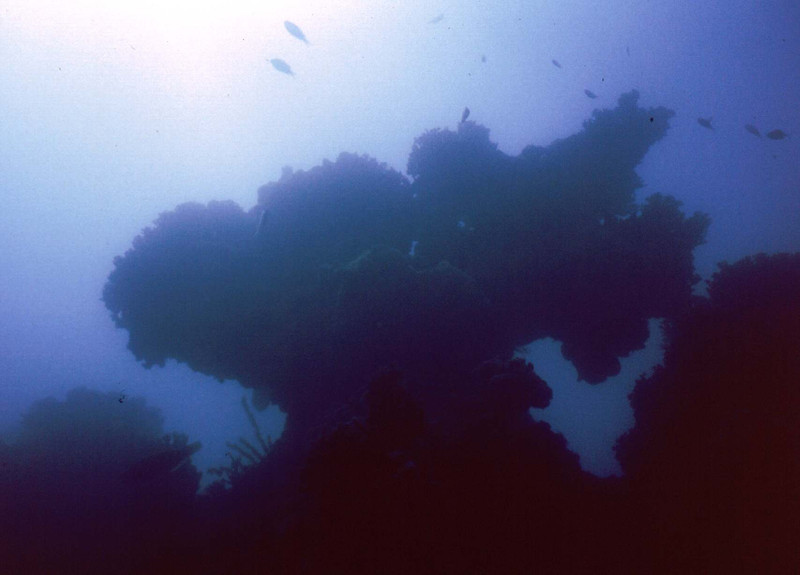

Where the Coral Grows Like Mushrooms

(Image credit: © Conservation International/photo by Tim Werner)

The only place to find this strange structure is along the northeastern coast of Brazil, in and around Abrolhos Marine National Park. This is the only spot on Earth to see chapeiroes, isolated coral columns that grow on the seafloor and have a mushroomlike structure. Chapeiroes come in different shapes and sizes, but the giant and mature chapeiroes of the Abrolhos Bank can reach more than 65 feet (20 meters) tall and 165 feet (50 meters) in diameter at their tops. According to Conservation International, an environmental group that works in the region, climate change threatens these unique reefs, so researchers are working to understand how the coral responds to changing conditions.

Where Tectonic Plates Meet

(Image credit: Andrew Frassetto)

Deep in the ocean, underwater mountains form as tectonic plates spread apart, with the boundary between these spreading plates forming a mid-ocean ridge as molten rock from below rises up to fill in the gap. To see a mid-ocean ridge with your own eyes, though, travel to Iceland, the only place where the mid-Atlantic ridge runs on land. This geologically active spot, also known as the Reykjanes Ridge, marks a rather fuzzy boundary between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. Because of unusually active volcanism at the ridge below Iceland, the area is like a blister on the top of this gash, oozing (and sometimes erupting) lava to the surface, which hardens into new crust.

Where the Life Is Very Old

(Image credit: Monica Johansen, Shutterstock)

To get a sense of how life on Earth used to be, visit Shark Bay, Australia, one of the very few places on the planet where you can see living stromatolites. These structures are rounded towers of sediment built over thousands of years by cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae. The stromatolites at Shark Bay are a few thousand years old, but they’re nearly identical to the life that thrived on Earth 3.5 billion years ago, when oxygen made up just 1 percent of the atmosphere. Though they’re found in a few extra-salty bodies of water around the world, stromatolites are at their most diverse and most abundant at Shark Bay.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.