Read - January 2016 — Loreli (original) (raw)

Showcasing new artists, writers, and musicians based in China.

Showcasing new writers in China. Posted February 2, 2016.

Introducing:

Thanh Le Dang

Thanh is pronounced Tan, like sun-tan. Her roots are Han Chinese from generations of migration from southern China to Vietnam and then to England London. Thanh is an artist writer and director born in London, she has been experimenting with her creative practice in Beijing now for just over a year and half, disguising herself ‘Laowai’ ways behind her Chinese face and learning 汉语 off her elderly neighbours in the hutongs. She set up ‘Scratching Beijing’ as a way for different artists to meet, collaborate and experiment with their and put on a show. Along the way she has found co-scratchers who believed in her creative cause, adopted a hutong cat and makes regular guilty visits to fried chicken man, a delicious hole in the wall fried chicken joint situated too conveniently close to her home.

Is China important in your life?

It always has been important wherein I'm Chinese by heritage. So I've always had to come here and learn the language. A year and a half ago it finally happened.

How about writing?

I realized I was dyslexic in university. I was really bad at writing essays. But in the last five years, I suddenly became relentless at writing. I was travelling, and got really drunk in a pub, and these voices just appeared in my head. I put the voices on paper, and started writing plays. Now I can’t live without a notebook ever.

How would you describe your voice?

When I think of characters, their voices often come to me first. Underlying their voice are the themes intrinsic in the story that I like to explore.

The last play I wrote, Chicken Shit, is about the relationship between a laowai [non-Chinese person] and a beautiful Chinese girl. And they are always swearing but don’t understand each other. She's trying to learn English and mimics him, and he being British he swears a lot. And this miscommunication is what moves the story along.

Tell us about your writing history and current projects.

I started playwriting in 2012, mostly short plays. They can be dark. I’m quite into monologues. The most notable character I do in Beijing is my character “Dong.” She is a brass, abrupt, Vietnamese woman. In England she was married to a rich English guy. But when she (i.e. me) came to Beijing, she adapted. Here, I noticed a lot of Vietnamese women marrying to Chinese men, especially down south. Because of the gender imbalance here, men have to look for marriage "solutions" abroad. On a train once I eavesdropped on a conversation about Vietnamese women running away with Chinese men’s money.

“It’s clear the Chinese media pigeon-holes these women. It’s in the newspaper and on the radio, telling women not to work so hard and to lower their standards. I can’t imagine really living in it. I feel the pressure around me because the first few questions you’re asked as a young woman here is, “What are you doing here?” “Do you have children?” and “Are you married?” Yes, sometimes the children question first. ”

So with Dong's first of two pieces in Beijing, Dong is married to a Chinese man, very very unhappily. The second one she leaves her husband and fucks a laowai in a toilet.

These pieces explore ideas of home. So I’m hoping to do a prequel to look at how she got to Beijing in the first place. I hope to travel to some border towns down south, and go through an NGO to see how and why the women have been through that.

Do you have a favorite word to use in your places?

I swear a lot. Chicken Shit was a whole script based on swearing. In London I had this promenade piece of this old granny swearing a lot. I enjoy the enunciation and the effects of swearing.

Describe the process of writing.

I most need relaxing in a pub and brewing over what to write, over a drink. The first step is hardest because you know the first draft you know is not going to be any good. You know that writing is mostly about rewriting. A good play would need about 6 or 7 drafts.

And about playwriting: writing the play versus working with actors and seeing it live are two different things. It’s difficult to see action just writing it.

How does writing and performing link up? Can you visualize it?

I do think visually; I was a concept artist for two years. I think a lot about stage direction and how things can be conveyed through action. An early piece on Dong shows her eating a mantou [Chinese bread roll] in a toilet. And it conveys a lot about her without any words. I think it helps the audience understand her a lot more and her fights with her husband.

How do you prepare a solo script for yourself?

I have to really get into the person. I filmed myself, which is odd for me because I’m animated, a more stage performer. But it’s important for me to see. I have this character Rita, who is 29-going-on-30 living with a cat. And that’s somthing I’m interested in here, as a woman who is 30 and also has a lot of Chinese associates who are 30. It's the kind of topic that always makes my audiences laugh uncomfortably – they don't know if they should laugh or not. And there's a fine line between comedy and tragedy, and I like to explore the line.

What do you think interests you about that?

Stand-up comedy is definitely one of the most daunting things I’ve done in Beijing. For me, I need a story, including my stand-up character. It’s not enough to just make the audience laugh; I want to interact with them.

I remember that after my grandpa’s funeral, me and my siblings got together in his room and shared a laugh. It was a wonderful thing.

Do you write for film or stage? What’s the difference?

The ideas will be the same. But with stage I can think more about how to use space, like in one play I wrote there was a theme of isolation and the use of space was important.

In film you can give more hints. On stage you need to be more dramatic to get those hints across.

You write a lot of interesting female characters.

So, my mom’s a massive influence in my work. She’s a refugee from Vietnam who moved to England in the late 70s. A very strong figure. Culturally she’s in between Vietnam and Britain, but she claims to be Chinese. In my house we speak a weird language of our own. Some speak Cantonese, some can’t. Mostly English, but with a lot of Vietnamese-isms that I didn’t realize were real English until I grew up. I am always interested in women immigrants and what they have in it for themselves – to throw their lives away and move to another country and marry a foreigner. And why? My pieces often look at these questions.

How do foreign languages play a role in your pieces?

The way you say something and how you say it means more than what you’re saying. Even in a foreign language. It makes audience pay attention.

What is the influence of China on your work?

On one hand I’m looking at leftover women. But as I look closer into the topic, I realize it’s all over the world. The other day I was on the phone to my mom and she was like, “Are you going to marry a nice Chinese boy and bring him home?” The idea of leftover women is happening in India too. Researching it now, it’s clear the Chinese media pigeon-holes these women. It’s in the newspaper and on the radio, telling women not to work so hard and to lower their standards. I can’t imagine really living in it. I feel the pressure around me because the first few questions you’re asked as a young woman here is, “What are you doing here?” “Do you have children?” and “Are you married?” Yes, sometimes the children question first. And they approach the topic so naturally.

I'm developing a piece on this topic right now called Introducing Rita (click to watch a preview).

How do you respond?

I just laugh. Like, “Who, me? No, no.”

Do you appear in most of your plays?

I don’t always intend to. I love writing and directing, and working with the actors. But there’s a bit of a problem here. One, I’m not Chinese enough to get Chinese actors and work with them in their language. Two, most expats here are white, so can’t play those Asian characters. I never got that into acting until I came to Beijing. In London I was a director.

Tell us about your ongoing art events – Scratching Beijing.

That's something I started last summer, derived from Scratch nights in London. Primarily it’s theatre. We are so limited from theatres to perform in, and people want to test their work. Coming from an artist background, I wanted to 1. Practice my art more; 2. Meet like-minded people here. So we’ve turned it into a multi-disciplinarian platform. We’ve had some really interesting collaborations, with dancing and acting and music – I think this is the essences of Scratches. It’s not about the finished product, it’s about experimenting with what can happen.

We don’t make any money from our shows; tickets are just to keep us alive. Keep the creative spirit.

“I hope to get more people involved. Beijing’s got very exciting energy. ”

Also, we are mostly teachers, and I’m a drama teacher. We’re doing some kids theatre, and its fascinating. For many of the Chinese kids, it’s their first time pantomiming, being on stage, saying things a certain way. I want to develop that a little more. I want to arrange a summer camp to take kids from Beijing to London. Got some connections there with an East Asian theatre, and we're aiming to bring over 20-30 kids.

I hope to get more people involved. Beijing’s got very exciting energy.

Whats your biggest dream for your writing?

I’m a traveller. I get itchy feet. Want to get travelling and writing and Scratching all over the place.

Any advice to young playwrights?

I don’t know, because I see myself as a young playwright. I’d say just go for it. Nothing to lose, right?

Introducing:

Matthew Byrne

"Poetry is Rock 'n Roll"

Posted January 22, 2016

Matthew Byrne graduated with an MA in Creative Writing from Manchester Metropolitan University in 2012 and has been writing, organising poetry nights and festivals, and taking part in workshops ever since. He co-edited the UNSUNG poetry magazine and organised UNSUNGfest in Manchester, both of which aim to shed light on poetry and provide poets with publicity.

Now he lives and works in Beijing and is the creator of SPITTOON, a monthly poetry night that seeks to bring Beijing's diverse group of poets together to share their work. SPITTOON also consists of a 'poetry-in-translation' segment, which explores poetry in other languages and its translations. So far the audience has enjoyed Chinese, Spanish, Arabic, Afrikaans and Mauritian Creole poetry, and Matthew invites anyone interested to get in touch and share poems in their mother tongues.

Matthew has also been published online and in anthologies in Britain. His poetry focuses on family, his experiences of holidaying in Ireland, and exploring our relationship with the small and seemingly mundane.

Shock

When a window is left open in the summer

because the air is thin honey

the admirer might forget to close it

and the room will take in night.

After a long evening the door will open

and the confection of past hours

will gush down the landing,

the slow smell of flowers and fading heat.

The breath of what’s left in the room

gets shocked into moths at a light switch,

their locations are a lottery,

they are randomly made out of night.

Shannon Trip

I

On the first day the air was thick cloth

and the waves were shedding themselves,

strange moths hung on boat like scales

or blinked in the river light.

I felt their presence around me,

older than the kings of Connaught.

When we passed through a half built town

that looked like an empty film set,

I saw the torn webs between the jetty rails

packed and twitching.

II

I woke to the sound of claws at around five

when the morning aches

and lay there trying to dream them away,

but they persisted. So I gathered my sleep up

and climbed the steps to the deck.

Through the translucent glass of the deck door

I saw our refuse bag speared by a gang of birds:

a mixture of rooks and seagulls.

One huge bird with a curved beak

scattered champagne corks, cake wrappers, hidden cigarette butts.

III

After an evening of laughing

we were restaurant fed and full of wine

so we retired back to our cabins.

Tired of irregular pleasantries

and eager to keep them fresh,

we had dined well. I even

dared to tell my father what I never tell him,

suitably hidden in a joke.

We had said enough to bring sadness

so we kept to ourselves and slept it off.

IV

Now that I have sadness in my thoughts

this memory defends itself;

the rough, plaster walls of Shannon View,

our family house.

As a child I drew my right hand across it

with my eyes closed

and I remember its rasping touch,

assuredly real.

It has become a brittle pewter memory

of action and light.

V

We moored a night near Lough Ree

and passed Shannon View the next day

having asked my grandmother

to meet us at the quay.

She waited smiling and wringing her hands

by the marina her father used to own.

For a moment she almost jumped aboard,

like she might have decades ago,

and we shouted no at that sketch of a girl.

I watched her through my binoculars watching us.

Mosquito

Once powerful infant in standing water

threshing meals in scum; blind wire of reflexes.

When you cracked through pupa and flew,

found your way in this pheromone gloom,

was it the walrus breath heaving

round the dark, drunken room

that lured you? Or from fog to fog

you found my drinking, smoking body?

When the light comes, you splatter red

like the others on the white wall.

Sharp calligraphy of a hit,

take my blood, make it insect.

Sometimes it strikes me

Sometimes it strikes me

that I might have missed love

when a small thought

of that straw haired girl

mimics my child heart,

I seek condolence in memories.

I watch lovers climb up the sunlight

dancing too hard and laughing too much

threshing gold out of their hair

onto sepia streets and shifting dust.

Does it ever strike you

that you might have missed love?

Like the leering groan of a missed train

as it creeps away slow then gone,

your lovers have bathed, tired of the living

with empires of feeling

they sleep on thrones

of whatever you've given them;

that first dance at the club

the sound she made when she forward rolled.

When did you realize that writing was an important part of your life?

When I was 17 or 18, I went to college, I was under-stimulated and ended up playing a lot of poker in my free time. I’d go home every night after a poker game and walk my dog, a beautiful black lab, and she’d go running high-speed into the hedges under the full moon ... and then it just hit me, that I just felt like writing. I didn’t like college, but I liked going home at night, walking my dog, and writing.

Do you have any recent projects?

I feel like I could have been more creative over the past three years in Beijing, but that being said, there’s a definite Beijing theme to my writings. There’s a lot of interesting things happening in the writing scene here. Some people have organized a workshop which brings together all the poets in Beijing and gives them a deadline to work with. I find it difficult to nail myself to the wall and work, so I work well with deadlines.

I’m looking to write a pamphlet about China. I think it’s interesting for people back home to read about your experiences here – to distill the experiences then bring them together in a pamphlet. It’s a New Year’s resolution to write more.

Favorite word to use in writing?

I like Ted Hughes – short, sharp. I don’t like writing poetry that uses words with too many syllables. I like to craft it and bring the music into the poem – bring out the music that’s already in the poem.

How do you describe the process of writing?

I have an analogy for this but it’s a bit rude. It’s like needing to go to the bathroom but not having the equipment for that. It feels like there’s a pressure inside, like a secret bladder you need to release. It seems very simple to sit down and write but it’s just not that simple. Whenever I am in the mood it’s not when I can sit down and write. So even though it sounds pretentious, I wish I could get a dictaphone.

“Mosquitoes consist of a magic. As if they could just land on a wall outside and through a process of osmosis go through the wall. They’re like pure evil. There’s something vampiric about them.”

You reference less-referenced insects like moths and mosquitoes.

Thanks for noticing that. When I was a kid, I was terrified of moths, the way they shuddered the light. I used to kill them as a kid, and then one time I got really upset about it. I actually woke up once in a moth in my throat, I breathed in a moth when I was sleeping, and in a way it’s quite an intimate relationship. There’s a certain mystery to them. I also had an intimate relationship with mosquitoes, as they pretty much infested my house in Beijing. Mosquitoes consist of a magic. As if they could just land on a wall outside and through a process of osmosis go through the wall. They’re like pure evil. There’s something vampiric about them.

I feel like your poetry references night and moon a lot.

I’ve always liked the ethereal quality of a moonlit night. It’s inspiring. Especially where I’m from in England, the countryside, it can be very beautiful. To answer very simply, I mentioned walking my dog during those college nights. It was a bit of a dark time. I starting smoking, listening to Mars Volta for the first time. I don’t know, but it was a time that lent itself to being a writer.

I find your poems to be descriptive and also reflective. Do you agree?

I’d agree, and … thinking about my poems featured on Loreli, there’s a poem with more hidden meaning, and that’s the one called "Shannon Trip." That poem was very interesting for me to write. It was written during this Celtic Tiger recession, you know there were all these ghost towns half-built, and you had this impression that the Irish, as soon as they got their hands on some money, they made these ridiculous towns. My point is, I grew up with an appreciation for the richness of Irish culture, having been raised by Irish people. So writing "Shannon Trip" was me trying to be reflective on Irish culture, in my recent trip to Shannon.

“The poems I write here are grittier, darker, and have more Beijing to them than when I was writing in England a few years ago.”

I think back now to when I was a younger man – which I can say now that I’m 27 – and how I’d just get up on stage and recite a poem I’d written and memorized. And they often weren’t very good, but I didn’t know that then. Since doing my MA, I’ve learned more about how to edit my own poems. I like to think of (poetry) as more of a science, something I can engineer. I like that – it allows me to be more reflective.

How has living in Beijing influenced your writing?

To be honest, the poetry I’ve written in China isn’t the most optimistic. And most of them aren’t particularly pleasant. I like to write about the canteen at work. What I mean by that is the regimented madness there, and the huge amounts of food that are processed through it. And I don’t know if I’m qualified to do this, but I want to write about being Chinese. Can I do that?

The poems I write here are grittier, darker, and have more Beijing to them than when I was writing in England a few years ago.

What do you hope for from your poetry?

I’ve always wanted to do poetry, since a young age, but I feel I’ve been too lazy. Recognition and fame would be nice, but really I just want to feel like I’ve done it. Carol Ann Duffy had dinner with someone once, who told her her poem “Prayer” was read at her aunt’s funeral. To know that this piece of work that you made is being read at someone you don’t knows funeral -- that would be my greatest dream.

Talk about your on-going poetry events at Spittoon.

You have to understand it in the context of UNSUNG. I used to run these UNSUNG events in Manchester, and it was raucous good fun. In Beijing now, at Spittoon, there is an incredibly international crowd, and you get a strong sense that there is a wealth of stories. Spittoon acts as a conduit to bring poets together but also to bring people from around the world, in Beijing. It's for them to contribute their own stories about their own countries. I just felt that all the energy was already there. There’s a great poetry night at The Bookworm, Word of Mouth, and I felt that there was enough energy for another poetry night. And it’s turning into a nice community of poets and people who love poetry.

What’s contributed to its success? Because at first there were only a few people, and now it’s like a packed house every time.

“I guess what I’m saying is get off your ass.”

A mixture of charm and intimidation. Apart from that, its informal nature. I think people have an impression that poetry is something done in a dusty lectern and you have to sit and listen to every word to understand it all. So when people come out to spittoon, they are surprised by the variety: slam poetry, page poetry, poetry-in-translation, people pouring their hearts out on stage. Like I said, it’s using the energy that’s already there, and shaping it. And people are having fun doing it.

So tell us about the poetry-in-translation.

Yes it’s a segment of the night, and it's a chance for people to hear the poem in its original language. First reading is its original, second reading is the English translation, and third reading is original again. This way, A. People become more aware of the country of origin. And B. people become more aware of the music of the poem. Because in translation, you lose a lot of the brilliant crafty of the original. So far we’ve had Afrikaans, Arabic, Maritian Creole, Chinese, and Spanish.

What do you think is the difference between listening to and reading a poem?

That’s an interesting question. In both situations you’re looking for something different. If you’re on your own, you may be looking for solace. You’re looking for something in a more introverted way. But in Spittoon, for instance, you’re drinking, with friends. There’s a chance the poet chose one of their more entertaining poems. And I really have faith in the crowd at Spittoon. The people who come take each poem for its merits, and don’t judge it, and don’t expect it to be entertaining. And that empowers the poets to write as they wish.

Advice to young writers?

Don’t be afraid to write. In a way I’m telling this to myself. If you write something you don’t’ feel is good, discard it and keep writing. Know that you’re good enough, and if you’re serious about it, you can really improve. Read a lot of poetry, go to poetry nights, go to workshops. Even if you think it’s a work of art, someone can always give you feedback. I guess what I’m saying is get off your ass.

And for people thinking of organizing a poetry event, just know that poetry is rock n’ roll. It really is. It’s so cool. I’ve run out of words now.

Introducing:

Simon Shieh

Posted January 14, 2016

Simon Shieh (1991) was born in Taiwan and raised in Hyde Park, New York until he turned 15, at which time he moved, with his family, to Beijing, China. Simon began writing poetry in middle school, but did not consider himself a serious writer until college, where he studied literature and creative writing at SUNY New Paltz and San Diego State University. Simon now works in Beijing as an Instructor at China Foreign Affairs University on a Princeton in Asia fellowship.

See Simon's work in Aztec Literary Review.

Fighting Words

These poems are part of a larger set that are inspired by my time living and training with the Sanda team at a sports academy in Yizhuang, China. When I was there in 2007, Yizhuang was a budding industrial suburb of Beijing — a city in the awkward throes of development, smelling all the time of coal. Sanda is a form of full-contact Chinese kickboxing that includes kicks, punches, take-downs and “sweeps.” Another boy and I were the youngest in the program at 16 years old. I was the only foreigner for miles, and much more privileged than my teammates, most of whom lived and trained there long-term. I have attributed to my teammates, in these poems, the names of Greek gods. In my young eyes, they very well could have been.

A Myth for Waking

Cellphones sing the sun

up — Apollo swats at his phone

and misses.

I hear darkness shatter

from my bed and feel sweat

tracing the narratives of my body.

What word do these drowsy beasts have

for daybreak? Say, a fingernail of sunlight

on a god’s sleeping face. Say

the wrong word and a stiff right-

cross will correct you. It’s 5:30 and I

forget how to be badly broken

forget to trade tired

for angry, a dream for the light

that fractures it. I dreamt fear

was a lick of palm salt and opened

to a fist under my cheek. It shakes

at the mention of lightning.

Coil nose, mustache bristle-whipped,

Zeus is at a loss for words this morning.

He rouses us like blood rouses the fur

coats in a crowd.

Six men wail

into flat pillows, bone

dry and dusty as the ginkgoes

guiding coal trucks through town.

Apollo curses the fiery mother

of daybreak and I see where the hoe

used to totter on his shoulder, hoping Zeus

wouldn’t lay hands on him for dreaming.

Ares cocks the phlegm

to his mouth and watches

it slap the floor.

We wait till we are as soft

as our black-blue thighs

before we struggle into our shorts.

I try to grunt but it comes out a whimper.

Nobody looks up from their shoe laces.

Morning Ritual

Every morning, I read my fate

in a milky way of salt clinging

to my shirt. I read rose

bushes by the door,

frayed bodies wilting

into sunlight, willing

the blood to our fingertips — I — first in fear

pluck thorns from the stalk and run

them under my fingernails.

There is nothing quite

like returning dirt to itself.

As my eye finds itself in a rusty

mirror, I see them almost

clothed, blurry as a backward

question: that is what?

Contact lenses, I reply, without them

you’re all color and no shape.

When we start running, even the track

needs waking up.

First footfalls on concrete echo

through my legs, the rosebushes looking

more like thorns with each lap.

Tell a rosebush its name

and it will weep over lost petals.

Ask why I’m here and I’ll show you

how I box my shadow out of a doubt.

We fool ourselves breathless — gasp

our heads out of water. Does breath

sound like a promise to you?

Origin says and unsays us blind:

six fighting men, thinking

with our bodies, howling

down the line until dawn is shaking

with surrender.

Zeus leads us in circles. A petal

for every breath that doesn’t ask

for blood.

Breakfast in the Hunchback’s Basement

Fire and oil make the white walls

heavy with morning light. Spice

stings the shadows out of a darkness

as daydreams catch sleep in their feathers.

Before long, I will be panting, slick

with spotlight. My fist, blood-beaten

as the evening cleaver, will be raised

to heaven or hanging from it.

The hunchback answers his angry

flame by flipping the onions

just beyond its reach.

Prometheus shakes

the empty table from his stool.

There is barely color

in his cheeks.

Yes, we have ducks in America and yes,

their love life is a mystery to us as well, I say.

Eggs were as rare as lovemaking

must have been for ducks

that July. Money can't buy

hunger, until you're huddled

in a hunchback's basement.

Fighters make money look like rain

in a drought. That summer, ducks snapped

a gold feather on their wings.

Does it outshine my busted right eye?

You’ll bite your tongue when

you see what kind

of woman will come running

to feed me.

II.

Steamed buns come in large

plastic bags from the boy who sells cigarettes

at the middle school. He’s quiet

until he’s swinging his fists at you — eyes

stale as a summer moon. Prometheus

says some shit about time and hunger then

burns the boy with five fingers.

Zeus rises from his seat.

His thighs tell me how easily

they woo a rib from its cage.

Imagine truth in a mouthful

of cold, hard teeth.

I shrink when Zeus returns

with his eyes on me, holding the first

fried duck egg this week. You

need it, he says, growing boy

like you, he says, home-

sick and always swinging

to please us, he says.

You kicked Prometheus so

hard the power went

out, and that’s why we like you.

You keep your words

to yourself.

A Dance with Weapons

All this toughening and

nobody’s taught me how to love

the fight. When Ares beckons me

to the ring I could vanish

into my name. Could be

a wisp of smoke sighing

from a frail pair of gloves. Can you

hear the doubt in my fists? Hook

to unhinge his whole fury. A snap

in the shoulder roll. Fugue

in dripping body light.

I drove my knee a cool centimeter into

the man’s skull before I touched

my wet cheek to his and

whispered thank you, man

in his ear.

We are thankful

for the damnedest things:

when the man facing me

can finish my

sentence about the way we hurt.

When he can strike me

tenderly because of the look

in my eye.

I’ve held a man’s courage

with two hands — it bled

through my fingers.

That is to say, I’ve loved something

untouchable.

“There was one point when I was struggling with the idea that maybe I’m a poet, maybe I’m not. But that’s bullshit. No one is a poet or isn’t a poet, you just make the decision to improve, or you don’t.”

1. What is the most memorable thing from your first year in China?

I'm from upstate New York, and moved to Beijing when I was 14 because my mom's a diplomat. That first summer in Beijing I enrolled in a sports academy in a dusty suburb of Beijing, called Yizhuang. You see it come up in my poetry. It was a kickboxing school, and it was thoroughly Chinese. No foreigners, no frills. It was a shocking introduction to China.

2. Moment you realized China was an important part of your life?

I guess I didn't realize that until after I left China. I left to go to college in the US. In the US, it's not so much that I didn't feel at home, it's more that there was a lot I suddenly couldn't do. Like go out to eat and drink, or use public transportation. My college was in a small town. It felt quite foreign. I realized then that China is where I wanted to be. So I applied for Princeton-in-Asia teaching program, and I got it. I was surprised when I came back to realize right away, that despite the pollution and the hard things about here, that I feel just right here. I feel at home in Beijing.

3. Moment you realized writing was an important part of your life?

Like many people do, I spent my teenage years writing angsty poems. After taking a course in college, I felt encouraged to take my poetry seriously. I had a shift in mindset from poetry being a therapeutic thing to an actual skill; something I could become good at.

4. Tell us more about your writing history and projects.

I'm mostly submitting to poetry and literature journals, and also applying for a workshop for Asian-Americans. Whether or not I get any of these, I'm still going to be writing. I wouldn't call it a hobby ... I also don't see myself getting an MFA right now. Poetry is something you can always do, and you don't need a higher education for that.

5. Do you have a favorite word to use in your writing?

You know, I do, and that's the bad thing. I like to keep using certain words. One accomplished poet said to me that he recognizes the words he uses a lot and then writes it down. It's not a bad thing to use the same words in a set of poems, but I try to stop myself from letting to words bleed over into other poems.

6. How would you describe the process of writing?

Something I have to set aside time for. For me there's a time for poetry and a time for essay-writing and research. I can't do both at once; I need to have a month in which I can focus on poetry, only read it, only write it. I need to be somewhere quiet, where I can read other people's poetry out loud and read my own out loud. It's solitary and vocal at the same time.

7. Could you give us some background to the poems?

Yeah, like I mentioned, I spent a month of my teenage years in this industrial city called Yizhuang, doing a kickboxing academy. And the routine was really weird to get used to. There were no TVs or computers or anything, so we'd get up, run, and then nap. We took three naps a day. I mean, they did -- I couldn't sleep. I didn't know what to do with myself. So the worst part of it was the boredom. I read four different books that month. It's hard to talk about the experience in a narrative way, because there's so much happening and it's so hard to put words to it. So I use poetry to talk about it.

I wasn't writing during that time though. I wrote one poem. A poem about the wind going through the window and freeing itself. Needless to say, it wasn't a good poem. I don't tend to write poetry when I'm unhappy. I was mostly just trying to survive.

8. Do you feel like the training itself influenced you in terms of being diligent with writing?

Yeah, I mean I've always been a serious, determined person. That discipline and routine that you need to be a professional athlete carried over into writing. It's helped me be a better writer.

9. In your poems you say you assign names of Greek Gods to your classmates at the kickboxing academy. How did you assign those names?

There was kind of a hierarchy to the group, and there were different personalities. Zeus was the head honcho, the one everyone looked up to, unofficially. Apollo was kind of this very lively and not-so-serious guy. Aires was this huge, hulking man, I'm pretty sure he was gay. I found that out in a strange way. I've got to figure out how to work that into the poems.

10. You talk a lot about emotional pain, in the poems. But not physical pain.

The thing about physical pain is it's only possible to write about it in retrospect. For a long time, I didn't know how to write poetry about fighting. For a while, those were my two passions: poetry and fighting. But I didn't know how to write about it.

There's a stress and trauma involved in fighting that's hard to conceptualize and put it into words. I had to distance myself and reflect on it to put it into the poems. I think the physical and emotional pain are working off one another. They're not mutually exclusive by any means. It opened up another way of writing about pain itself.

11. You wrote in 'Morning Ritual' about being the only foreigner in the school.

When I first got there, we were both foreign to each other. I was weird. But that being said, I think that was integral to the camaraderie. They were so hospitable. They were very, very kind to me. They took care of me, and if I were not an outsider, I wouldn't have been received in the same way. So yes, I was a foreigner, but because of that foreign-ness, I was treated a certain way, and our camaraderie was built around that dynamic.

12. In the poem, you talk about food. And there's a sense that food is almost idolized as this rare and precious gift.

Before I had this experience...I'll put it this way. The experience made me think of hunger and desire in a certain way. I had never been so conscious of wanting something. I was reading Angela's Ashes when I was there, about this family in terrible poverty. I read about them eating strawberry jam, and that really got to me. It sounds so trivial and stupid, but this experience made me aware of these visceral needs we have. And it really amplified my desire, and in a real sense, my hunger.

13. I get a sense that there is a competitiveness that extends beyond the ring. Was this the atmosphere for you?

Fighting is different from other sports wherein in other sports, there's this distance between the abstract concepts of winning and losing. But in fighting, you really feel the win or the loss in a very close way. You feel literally beat up. So because there was so little distance between the sport and what was happening in the sport, and what you were feeling, everything was very literal. Even outside of training, there was always this understanding that although it brought us together, there was always some competitive tension. We knew that the next day we would have to hurt each other in a very real sense. On a whole though, it really brings combat sports athletes together.

14. It sounds like you and your teammates really respected each other. What granted that respect?

This goes back to the last question. For fighters, the respect is always very mutual. Because I know best how he feels, and he knows best how I feel, and there needs to be some element of respect to keep the sport from becoming something much uglier, which it never really is. Respect is necessary in a sport like fighting, because if it's not, neither of the fighters can do their job. They would devolve into an animal's show of aggression and force.

15. Does this physical exertion and expression still inspire you to write?

I haven't figured out how, but it does. I've since "retired" from professional fighting, as a career. I teach English now, and focus on writing. Like I said, I didn't know how to write about fighting until recently. I'm still figuring it out.

16. So what are your inspirations now?

Hm, hard question. Other poets inspire me ... I don't know why this is so hard to answer. OK, this is going to sound cliche, but the ability to share my experience in a meaningful way is what really inspires me to write. I think there are a lot of experiences that I can only share through poetry.

17. What advice would you give to other young writers?

When I was a young writer, the few poets I know would always tell me to keep writing. I never knew what that meant, so I don't want to say that now. But it is important to not give up. They'd also tell me that, and I didn't know what it meant. Writing is not this magical thing that you're born with. No one is more pre-disposed to it. Just keep reading and writing. That's the only way to improve. To be conscious of the fact that you're always improving. There was one point when I was struggling with the idea that maybe I'm a poet, maybe I'm not. But that's bullshit. No one is a poet or isn't a poet, you just make the decision to improve, or you don't.

Introducing:

Kassy Lee

Posted Jan 6, 2016.

Kassy Lee helps twenty-somethings who struggle with finding real work to match their passion discover and create a vocation that serves their soul and sustains their financial independence. She's also a published poet and world traveler currently living in Beijing. She offers a free audio course on gaining confidence to go after your creative career.

***

THE SCREW, THE CLOUD

Honey is a chalk miner’s daughter.

She straps me to the cinder blocks

since I am her peach internal ear.

Since we drink root beer on Daddy’s

porch, Honey, come spring, polishes off

my temporary ghost like string

cheese. A soul peels the way that

cheese does, slow. Sand rats come and go

with the knowledge that I should also

remain anonymous. Fruit bats

swarm in the burnt out barn by our

sworn silence. Bumper cars jar me

to sleep in the Santa Ana winds.

Honey presses her bandana

against me like a road sign sandstormed

against the earth, warmed in a heat

impossible to get through unless

you know the Pacific brews blue

beyond the mountains. She scatters trash

beyond pissed-on grass we watch turn

yellow, slow, like brown kids in winter

who go to good schools in small towns

out east. It means nothing to me. Far

out in a coal tar noon, the cold sun

drudges past in its honeyed cast.

***

THESAURUS dot COM

Claret, maybe? A simple Kool-Aid rued hue. Inside, the body of someone

who hates me. Outside, a tree muscles out its raw fruits. The gentle arc of

the moon laps up the blood. A puddle of which is subject to the same forces

as the tidal ebb and flow. The bay window chafes my outer thigh as we make

love. The goldfish knows. He doesn’t grow jealous. I was charmed by sweet

kernels of corn between your gap-tooth, the boy with the Dead Sea cosmetics

booth, the ripples of a wound. Even if you believe that the horizon is a snake

with its tail on its own tongue, a kid on my Chrome browser will still be dead.

You’ll go on trying to overanalyze my texts. I’ll go on with my cellphone

camera, recording my nephew killing roaches with Raid in order to play it

back in reverse. Death happens only once, and then all is rewound. God can

make a rusty revolving chamber, like your heart. God can make a military

grade tank on a sunflower-hugged highway. That’s within his means. God

can make pies as wide as July, a silvered token for the misappreciation

of your body. He can do whatever he likes except prove that all of us are

made in his image. For some reason he can’t do the math on that one.

It’s just that, well, every cloud has a brutal body bag lining. When we are

abstract, we can be so beautiful. But, we are concrete. We are gray, draped

by the bodies of teenagers killed on their way to their grandma’s house.

Killed while thinking, Will there be any cute girls in technical college?

Just some city girls with their tight coils in the dead air of the dayroom.

***

TENDER GREENS

I meet the meat slicer. I meet the deli counter.

The butcher boy has his perfect speed. He might

be the half-soup, half-sandwich combo meal deal

of my dreams. I’ve been told there’re mountains

haloing the city in the distance, but where the fuck

are they when you need them? Since I’ve moved

here all I can see is the high spire poking out from

the convention center. After all, this seizing of my

heart around its blood bags is as plain as plain yogurt.

A monogrammed dish towel in an orchard of fruit

-bearing trees, now that’d be the stuff. I start to “talk”

with God to pass the time, but after a while I spend

the nights at His place. He will at least set an alarm

for me to wake up before Him so I can get my ass

to work on time. The angle of His pulpwood scar

makes me feel like a jukebox playing, “What’s Up

Pussycat” ad nauseam in a moonlit diner. Of course,

after another while God gets bored of my fake sex

noises. He leaves the TV room shouting things like,

“My Easy Bake Oven, my silent beauty, my jealous

pizza, guacamole costs extra but only ninety-nine

cents extra. Think of all I’ve done for you!” He comes

back in after checking the crevice behind His comfy

couch for the Roku remote. I need Him more than

He needs me. I know, I know, okay. I whisper. I wave

the celadon sweet laundry softener above my head.

I read a Cosmo.com article about emotionally

unavailable deities, and I ask God if He thinks

He’s emotionally unavailable. “C’mon, girl, I’m

watching Game of Thrones,” He says. The voice

of God saying, “C’mon girl, atta girl, good girl.”

That’s what ropes me in when I think of leaving

Him and changing my Facebook profile pic for

good. I blow Him and bang my skull against His

desk in a casual rhythm. He makes a joke about

knocking the sense into me. I joke that I’d rather

have some cents instead of sense. It’s not a very

funny joke, but I’m not a very funny person

either. It’s a universal test of personal will

and devotion to be God’s small lamb and fuck-

around-girl. It leaves me wondering, Am I the

type to be told I am beautiful against the gentle

to and fro of the whipsaw? Or am I the whipsaw?

***

1. What’s your most memorable moment from your first year in China?

One night I was out at Houhai with a friend. It was one of those "domino effect" evenings of small events. First we see these guys flashing laser lights, but we don't buy those, we buy bubble guns instead. Which leads us to buying a deck of cards, and playing card games. And then all the old men gathered around and watched us playing cards. It just typifies China as a "one thing leads to another" situation.

2. The moment you realized China was an important part of your life?

I never studied China or thought I would live here before a year and a half ago. I was very ignorant of China. In my first year here, one of the first things I noticed was how excited the city was for the iPhone 6. There were images all around town and you could sense a pervasive excitement. Around that same time in America we were having a lot of problems with police brutality. I felt oddly more connected to the iPhone fervor here than the protesting fervor in my country, like there was a disconnect. That’s when I realized I really live here.

3. Is that where your poem 'The Ghost of Steve Jobs' came from?

Yeah! I was going around town to different cafes reading and writing, and I kept overhearing people talking about him. I was at Tribe when heard some people say that when iPhone 5 came out, people stayed overtime in their offices just to keep playing with it. I didn't really think about Steve jobs when I was in America, but I can’t help but think about him here.

Before I came to China, US imperialism was a big focus of my writing. But in China it’s really different than in Africa or Latin America, US culture has a history of crumbling other cultures. In China it’s not as one-directional. There is more of an interplay.

4. What's the moment you realized writing was an important part of your life?

I was 7 years old. A woman who was a poetry workshop freelancer came to our school, held a few workshops. She got us tickets to a Maya Angelou reading. Maya Angelou was kidnapped and abused as a child for a few weeks. Her Mom heard from people talking in the streets where her daughter was, and she went and bust down the door. The abuser ran away and Maya was rescued. A few weeks later, they found the abuser, dead. Maya felt like she had killed him with her words -- by divulging what he did to other people. That's when she realized the power of her words -- that they can devastate or heal people.

Listening to Maya Angelou tell this story, I also realized it.

5. Your writing history and current notable projects?

I was in a kid's writing group called “Border Voices,” because grew up on US-Mexico border. My mom was a psychiatrist so I’d write a lot about drug abuse. Even though it wasn’t a problem in my family, my mom would drive me to school and I'd listen to her talking on the phone. So I picked up a lot of the talk early on.

I went to Columbia, and lived in a poetry house live with other poets and writers, which was super cool but got pretentious sometimes. It was like, "Hey I don't feel like talking about TS Elliot again, can we just have a beer and chill?" But I got to meet lots of awesome poets.

After I graduated I published Zombia, a chapbook, about zombie history. Zombies come from slavery times in Haiti. This idea that if you’re a slave and kill yourself, you become a person in between life and death. In the US, suicide is seen as a white person's thing, like people of color are supposed to suck it up and go to church or whatever. Which was a big struggle for me when facing hard times.

After college I went to Guatemala, so got Spanish influence in my work. Now I’m in China, working on a chapbook that’s kind of sci-fi. There's a lot of internal conflict in the US, so I'm writing it as if we're 70 years in the future looking back on the US as it sank into Civil War. As if the US became one of those "old countries" like Prussia -- a place you've heard about but know nothing about since its collapse.

6. Favorite word in writing?

Lattice. Words with “Bone.” And “oo” sounds like “swoon.”

7. One word/sentence/phrase to describe the process of writing?

“There.” Because when I’m writing it’s the only time in my life I feel completely present. And it’s cool when you get in that state, then come out of it, and realize, “Wow, I wasn’t thinking about anything else!”

8. Why is poetry your greatest passion and why does society fail to recognize its value?

Poetry says everything about life. If you look at every culture, you’ll see that every culture has an oral or written poetry tradition. Most people when they’re kids are writing poetry but don't realize it. That's how the soul expresses itself.

“Zombies come from slavery times in Haiti. This idea that if you’re a slave and kill yourself, you become a person in between life and death. In the US, suicide is seen as a white person’s thing, like people of color are supposed to suck it up and go to church or whatever. Which was a big struggle for me when facing hard times.”

Why undervalued? Because there’s a disconnect between how people learn about poetry and how they enjoy it. In the States we learn about old poems, and all their references, you feel stupid not getting those references. Nowadays when I show a poem to a friend outside the poetry world, they usually say “I don't understand it”, and I’m like “You don't need to understand it! We love songs, the lyrics of the song, but no one feels pressured to unlock some hidden mystery." I think universities want professors who understand poetry deeply, but poetry isn’t just meant to be understood like that.

You could say right now, that popular poetry is in song lyrics. That's the poetry of our age. Most conventional poets need to live in universities and become professors to survive, so they get more academic. But the internet is helping by taking away the gate-keepers. Making poetry cool.

9. I read a review of your works that said the disappointing political sphere in your teenager years was a big influence on your works. Do you agree?

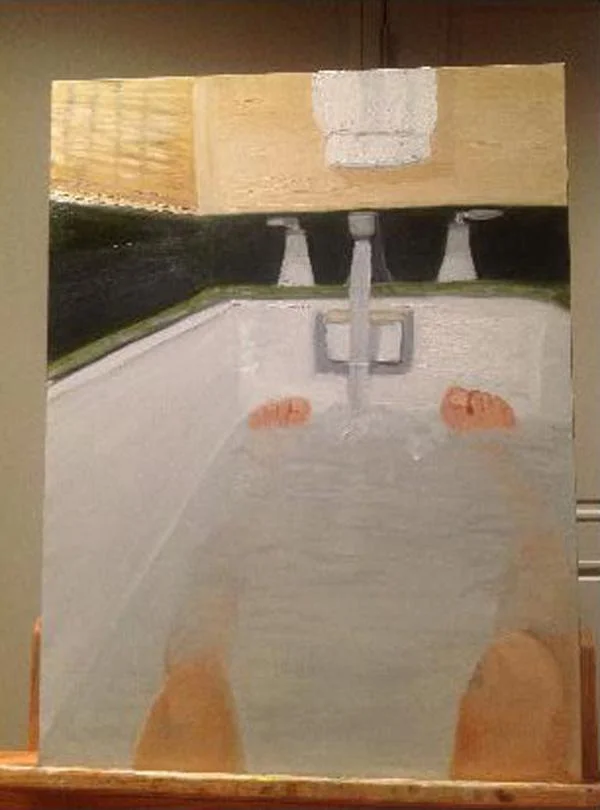

Big time. I wrote one poem in the chapbook called “George bush paints puppies.” He made news again 3-4 years ago because he was painting but would only paint puppies. There’s one of him in the bathtub that just shows his feet.

He was president from 10-18 for me. I grew up in San Diego, which is 1/3 White, 1/3 Hispanic, and 1/3 Asian, with some Black and Native American too. The playground would have lots of langauges. And the Bush years were very tough on immagrants. Lots of racism, and 9-11 added to that, calling immigrants terrorists. Now I realize that this is just what America is, it’s not just because of Bush.

It’s weird as an American feeling disappointed and helpless b/c you see your government doing terrible things, and you can only vote for one side of the same coin.

10. Your poetry combines raw images and dark topics with modern references and humor. I really like that. Is this a conscious decision?

There's an element of agency. Agency meaning someone having the ability to make choices in their life. Like in the US, you can’t choose to vote for someone who isn’t perpetuating our empire. And I feel I don’t have political agency in that way. In many ways we are always operating in a realm of choiceless-ness, and it’s funny how similar people are in how they deal with it. You have an existential process of the meaningless-ness of life, and at the same time you’re dieting on kale and Facebook-ing your ex boyfriend, and your day-to-day just looks like anyone else’s. Watching Youtube videos about pandas going down slides.

The consciousness levels of life are like, you can be trying to figure out meaning in your life, and meanwhile thinking “I got to lose weight’ or “I want to check out this guy’s OKCupid profile but he can see I’ve done it but I can’t help myself!”

11. How do you describe the voice that you’ve developed as a writer?

That’s something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. As a student, your voice molds to a university setting. Or mimics other poets. Now it seems like popular good poets just write about nature and flowers and horses. I don’t know the names of any birds, so I couldn’t do that. I wouldn't want to. Recently I heard a birdsong and I thought it was an alarm, so I was like, “Fuck that person’s alarm,” but then I realized it was a real bird. So my reality is that if I go into nature, I’m like, “Oh my God this looks like the Indiana Jones ride at the amusement park in San Diego.” My reality is more synthetic.

“My first reality is the synthetic reality.”

I want to elevate that reality. Like going into the grocery store and there's a million toothpastes and you have an existential crisis about it. It’s easier with scenic themes to play with language because language is made for those scenes. It’s harder to play with contemporary items,

Also, I’m a Black poet, but I don’t speak with the so-called Black vernacular. Neither do people in my Black community. So I’m conscious of what it means to be a Black writer versus White writer, and an American abroad -- it’s all unclear but I just try to be authentic to the way I listen and hear and see the world.

12. You refer to God in some poems. What role does god play or represent in your poems?

Yeah, right? I talk to God a lot in my poetry. But in real life I feel more like we're in the movie Interstellar, where you have a timeless self in a container who is always looking out for you. Sometimes I feel like I’m communicating with my timeless self.

This is an interesting part of being alive now. We’re not bound by the ethical code of any religion -- we’re free. But we’re also lonely. Like, God in my poems is this being who can listen to me in my darkest states and is trying to do the best for me but I keep messing up. And God is like, “Come on, man, what are you doing now?”

If you’re a contemporary city-dwelling person and well-educated and family is not religious, you might feel like, “What even is this God thing?” We can’t picture how he fits into our contemporary lives. What is he? Steve Jobs?

13. Your posts are largely multi-media, and I want to talk to you about the purpose of incorporating GIFs and video into your work.

I love the internet. It’s who I ask for advice. I Google specific things, like, “How to get my socks to stop falling down in my boots.” I think this goes back to what our reality is now, which is life through a screen. It’s how we relay emotions now. Sending out GIFs of partying to show we’re excited for a party.In short, multimedia helps me express everything I need to express.

I feel some of my deepest convos have been over G-Chat – how do I capture that? On a daily basis, friends will send videos to each other, same as talking. We share emotions through Youtube videos: "Haha this is so funny, watch this video."

Me and my friends are continual sharers, and it’s like a continual archive of what you have with them. It's kind of beautiful.

14. What advice would you give to young writers and artists?

This is the best advice but it always sounds stupid. “Just write, and keep writing.” Stop reading advice about how to write and start writing. You’ll come up with a million and ten reasons not to write, and looking for advice on how to write is one of those.

January Curator:

Charlotte Smith

Charlotte is a nomad multipotentialite whose various projects, creative pursuits and side hustles can be explored at https://clisviolet.journoportfolio.com/. She deeply values connection and the exchanging of ideas. Her greatest accomplishment has been finding people who are a continuous source of inspiration. (Photo credit: Phillip Baumgart)

Scan to follow us on WeChat! Newsletter goes out once a week.

We respect your privacy

Thank you!