How soy sauce is made (original) (raw)

Background

Soy sauce is one of the world's oldest condiments and has been used in China for more than 2,500 years. It is made from fermenting a mixture of mashed soybeans, salt, and enzymes. It is also made artificially through a chemical process known as acid hydrolysis.

History

The prehistoric people of Asia preserved meat and fish by packing them in salt. The liquid byproducts that leeched from meat preserved in this way were commonly used as liquid seasonings for other foods. In the sixth century, as Buddhism became more widely practiced, new vegetarian dietary restrictions came into fashion. These restrictions lead to the replacement of meat seasonings with vegetarian alternatives. One such substitute was a salty paste of fermented grains, an early precursor of modern soy sauce. A Japanese Zen priest came across this seasoning while studying in China and brought the idea back to Japan, where he made his own improvements on the recipe. One major change the priest made was to make the paste from a blend of grains, specifically wheat and soy in equal parts. This change provided a more mellow flavor which enhanced the taste of other foods without overpowering them.

By the seventeenth century this recipe had evolved into something very similar to the soy sauce we know today. This evolution occurred primarily as a result of efforts by the wife of a warrior of one of Japan's premier warlords, Toyotomi Hideyori. In 1615 Hideyori's castle was overrun by rival troops. One of the warrior's wives, Maki Shige, survived the siege by fleeing the castle to the village of Noda. There she learned the soy brewing process and eventually opened the world's first commercial soy sauce brewery. News of the tasty sauce soon spread throughout the world, and it has since been used as a flavoring agent to give foods a rich, meaty flavor.

Today soy sauce is made by two methods: the traditional brewing method, or fermentation, and the non-brewed method, or chemical-hydrolyzation. The fermentation method takes up to six months to complete and results in a transparent, delicately colored broth with balanced flavor and aroma. The non-brewed sauces take only two days to make and are often opaque with a harsh flavor and chemical aroma. Soy sauce has been used to enhance the flavor profiles of many types of food, including chicken and beef entrees, soups, pasta, and vegetable entrees. Its sweet, sour, salty, and bitter tastes add interest to flat-tasting processed foods. The flavor enhancing properties, or umami, of the soy extract are recognized to help blend and balance taste. The condiment also has functional preservative aspects in that its acid, alcohol, and salt content help prevent the spoilage of foods.

Raw Materials

Soybeans

Soybeans (Glycine max) are also called soya beans, soja beans, Chinese peas, soy peas, and Manchurian beans. They have been referred to as the "King of Legumes" because of their valuable nutritive properties. Of all beans, soybeans are lowest in starch and have the most complete and best protein mix. They are also high in minerals, particularly calcium and magnesium, and in Vitamin B. They have been cultivated since the dawn of civilization in China and Japan and were introduced into the United States in the nineteenth century. In the 1920s and 1930s, soybeans gained popularity in the U.S. as a food crop.

Soybeans are short, hairy pods containing two or three seeds which may be small and round or larger and more elongated. Their color varies from yellow to brown, green, and black. The variety designated yellow #2 are most commonly used for food products. These soybeans get their name from the yellow hilum or seed scar which runs down the side of the pod. The grades of grain allowed for trading are established by the United States Grain Standards which are administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Soybeans are unusual in that, unlike other grains, most are used in processing or exporting, and not much as direct animal feed. This is because soybeans contain "anti-nutritional" factors that must be removed from the beans before they can be of nutritional value to animals. The soybeans used in soy sauce are mashed prior to mixing them with other ingredients.

Wheat

In many traditional brewed recipes, wheat is blended in equal parts with the soybeans. Pulverized wheat is made part of the mash along with crushed soy beans. The nonbrewed variety does not generally use wheat.

Salt

Salt, or sodium chloride, is added at the beginning of fermentation at approximately 12-18% of the finished product weight. The salt is not just added for flavor; it also helps establish the proper chemical environment for the lactic acid bacteria and yeast to ferment properly. The high salt concentration is also necessary to help protect the finished product from spoilage.

Henry Ford demonstrates the durability of automobile components made from saybeans by striking the trunk of a car with an axe.

(From the collections of Henry Ford Museum & Greenfield village.)

American farmers produced surpluses of many agricultural commodities in 1930, but soybeans were not one of them. During the early years of the Great Depression, few farmers raised soybeans, but this changed in just 10 years. In 1929, American farmers produced less than 10 million bushels (352 million L) of soybeans. By 1939 production approached 100 million bushels (3.5 billion L), and in 1995, American farmers raised more than 2.1 billion (74 billion L) bushels of soybeans. No one surpassed Henry Ford as a promoter of soybean production in the 1930s.

In 1929, Henry Ford constructed a research laboratory in Greenfield Village and hired Robert Boyer to oversee experimentation related to farm crops. Ford hired additional scientists to investigate the industrial uses of many agricultural commodities, including vegetables such as carrots. The greatest success was in soybean experimentation. The researchers developed soy-based plastics and made parts for automobiles out of the products. The scientists manufactured ink made from soy oil, and produced soy-based whipped topping. Many of these processes and products remain in use.

Ford believed that farmers should have one foot on the soil and the other in industry. Ford promoted agricultural production of soybeans through an exhibit in a barn at the Chicago "Century of Progress" World Exposition in 1933. He hosted a meal which included a variety of soybean items and supported the publication of recipe booklets full of soybean-based recipes.

Henry Ford wished to see farmers to produce soybeans on their farms and process them for industrial purposes. Though his vision was not realized, the importance of soybeans in American agriculture came to fruition. Soybeans are one of most important crops raised in America, and provide American farmers millions of dollars in income.

Leo Landis

Fermenting agents

The wheat-soy mixture is exposed to specific strains of mold called Aspergillus oryzae or Aspergillus soyae, which break down the proteins in the mash. Further fermentation occurs through addition of specific

bacteria (lactobaccillus) and yeasts which enzymatically react with the protein residues to produce a number of amino acids and peptides, including glutamic and aspartic acid, lysine, alanine, glycine, and tryptophane. These protein derivatives all contribute flavor to the end product.

Preservatives and other additives

Sodium benzoate or benzoic acid is added to help inhibit microbial growth in finished soy sauce. The non-brewed process requires addition of extra color and flavor agents.

The Manufacturing

Process

Traditional brewed method

Brewing, the traditional method of making soy sauce, consists of three steps: koji -making, brine fermentation, and refinement.

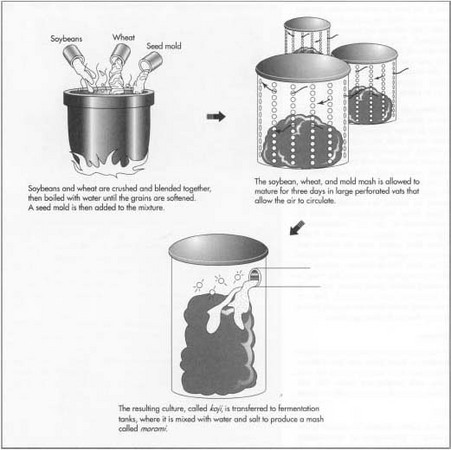

Koji-making

- 1 Carefully selected soybeans and wheat are crushed and blended together under controlled conditions. Water is added to the mixture, which is boiled until the grains are thoroughly cooked and softened. The mash, as it is known, is allowed to cool to about 80°F (27°C) before a proprietary seed mold (Aspergillus) is added. The mixture is allowed to mature for three days in large perforated vats through which air is circulated. This resulting culture of soy, wheat, and mold is known as koji.

Brine fermentation

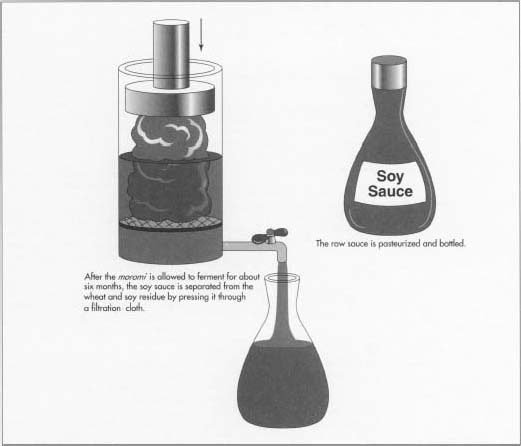

- 2 The koji is transferred to fermentation tanks, where it is mixed with water and salt to produce a mash called moromi. Lactic acid bacteria and yeasts are then added to promote further fermentation. The moromi must ferment for several months, during which time the soy and wheat paste turns into a semi-liquid, reddish-brown "mature mash." This fermentation process creates over 200 different flavor compounds.

Refinement

- 3 After approximately six months of moromi fermentation, the raw soy sauce is separated from the cake of wheat and soy residue by pressing it through layers of filtration cloth. The liquid that emerges is then pasteurized. The pasteurization process serves two purposes. It helps prolong the shelf life of the finished product, and it forms additional aromatic and flavor compounds. Finally, the liquid is bottled as soy sauce.

Non-brewed method (chemical hydrolysis)

Instead of fermenting, many modern manufactures artificially break down the soy proteins by a chemical process known as hydrolysis because it is much faster. (Hydrolysis takes a few days as compared to several months for brewing.)

- In this method, soybeans are boiled in hydrochloric acid for 15-20 hours to remove the amino acids. When the maximum amount has been removed, the mixture is cooled to stop the hydrolytic reaction.

- The amino acid liquid is neutralized with sodium carbonate, pressed through a filter, mixed with active carbon, and purified through filtration. This solution is known as hydrolyzed vegetable protein.

- Caramel color, corn syrup, and salt are added to this protein mixture to obtain the appropriate color and flavor. The mixture is then refined and packaged.

Sauces produced by the chemical method are harsher and do not have as desirable a taste profile as those produced in the traditional brewed manner. The difference in taste occurs because the acid hydrolysis used in the non-brewed method tends to be more complete than its fermentation counterpart. This means that almost all the proteins in the non-brewed soy sauce are converted into amino acids, while in the brewed product more of the amino acids stay together as peptides, providing a different flavor. The brewed product also has alcohols, esters, and other compounds which contribute a different aroma and feel in the mouth.

In addition to the brewed method and the non-brewed method, there is also a semi-brewed method, in which hydrolyzed soy proteins are partially fermented with a wheat mixture. This method is said to produce higher quality sauces than can be produced from straight hydrolysis.

Quality Control

Numerous analytical tests are conducted to ensure the finished sauce meets minimum quality requirements. For example, in brewed sauces, there are several recommended specifications. Total salt should be 13-16% of the final product; the pH level should be 4.6-5.2; and the total sugar content should be 6%. For the non-brewed type, there is 42% minimum of hydrolyzed protein; corn syrup should be less than 10%; and carmel color 1-3%.

In the United States, the quality of the finished sauce is protected under federal specification EE-S-610G (established in 1978) which requires that fermented sauce must be made from fermented mash, salt brine, and preservatives (either sodium benzoate or benzoic acid). This specification also states that the final product should be a clear, reddish brown liquid which is essentially free from sediment. The non-fermented sauce is defined as a formulated product consisting of hydrolyzed vegetable protein, corn syrup, salt, caramel color, water, and a preservative. It should be a dark brown, clear liquid.

The Japanese, on the other hand, are more specific in grading the quality of their soy sauces. They have five types of soy sauce: koikuchi-shoyu (regular soy sauce), usukuchi-shoyu (light colored soy sauce), tamari-shoyu, saishikomi-shoyu, and shiro-shoyu. These types are classified into three grades, Special, Upper, and Standard, depending upon sensory characteristics such as taste, odor, and feel in the mouth, as well as analytical values for nitrogen content, alcohol level, and soluble solids.

Byproducts/Waste

The fermentation process produces many "byproducts" that are actually useful flavor compounds. For example, the various sugars are derived from the vegetable starches by action of the moromi enzymes. These help subdue the saltiness of the finished product. Also, alcohols are formed by yeast acting on sugars. Ethanol is the most common of these alcohols, and it imparts both flavor and odor. Acids are generated from the alcohols and sugars, which round out the flavor and provide tartness. Finally, aromatic esters (chemicals that contribute flavor and aroma) are formed when ethanol combines with organic acids.

Chemical hydrolyzation also leads to byproducts, but these are generally considered undesirable. The byproducts are a result of secondary reactions that create objectionable flavoring components such as furfural, dimethyl sulfide, hydrogen sulfide, levulinic acid, and formic acid. Some of these chemicals contribute off odors and flavors to the finished product.

The Future

The future of soy sauce is constantly evolving as advances are made in food technology. Improved processing techniques have already allowed development of specialized types of soy sauces, such as low-sodium and preservative-free varieties. In addition, dehydrated soy flavors have been prepared by spray drying liquid sauces. These powdered materials are used in coating mixes, soup bases, seasoning rubs, and other dry flavorant applications. In the future, it is conceivable that advances in biotechnology will lead to improved understanding of enzymatic reactions and lead to better fermentation methods. Technology may someday allow true brewed flavor to be reproduced through synthetic chemical processes.

Where to Learn More

Books

Farrel, Kenneth T. Spices, Condiments and Seasonings. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company Inc., 1985.

Periodicals

"A Tale of Two Soy Sauces." Prepared Foods, October 1996, p. 57.

The Soy Sauce Handbook, A Reference Manual for the Food Manufacturer. Kikkoman Corporation., 1996.

— Randy Schueller