Florence Foster Jenkins on maxbass.com (original) (raw)

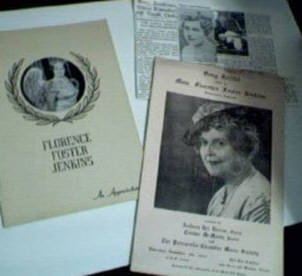

Articles about Florence Foster Jenkins

Click on CD for audio samples

Liner notes from the CD

The Glory (????) of the Human Voice

By Francis Robinson

Few artists ever gave such unalloyed pleasure as Florence Foster Jenkins, yet this extraordinary soprano had the wisdom not to overdo a good thing.

She emphatically declined to appear in New York oftener than once a year and rarely anywhere else except such favored centers as Washington and Newport. For years her annual recital at the Ritz-Carlton was a private ceremonial for the select few--her stubbornly loyal circle of clubwomen and the adventurous cognoscenti. If the latter at times displayed an unmannerly lack of restraint they were nonetheless faithful.

Music critics covered the event in precisely the same reverse English with which they frequently, though perhaps less intentionally, leave a baffled public speculating as to what actually did happen the night before. Then the word began to get around. Tickets became harder to come by than for a World Series. Finally, on the evening of October 25, 1944, Madame Jenkins took the big step. Forsaking the brocade atmosphere of a fashionable hotel ballroom, she braved Carnegie Hall.

There are those who claim that her death one month and a day later was the result of a broken heart--as unlikely as the story that her career was all a huge joke at the public's expense--a pretty expensive joke, incidentally, since Carnegie Hall was sold out weeks in advance and grossed something like $6,000. Moreover, the late Robert Bagar wrote in the New York World-Telegram: "She was exceedingly happy in her work. It is a pity so few artists are. And the happiness was communicated as if by magic to her hearers..."

No, Madame Jenkins died full of years--76 to be exact--and, it is safe to say, with a happy heart.

Neither her parents nor her husband gave any encouragement whatever to her musical ambitions, but with her divorce and the money inherited from her lather, a Wilkes-Barre banker and lawyer who had served in the Pennsylvania legislature, she was free to turn her sights on new York. She broke into print in 1912 as chairman of the Euterpe Club's tableaux vivants. She was also glad to foot the bill for the annual spree of her Verdi Club. The lavishness of this entertainment may be guessed from the name under which it went--"The Ball of the Silver Skylarks."

All this gave free rein to her hair for costume design, a faculty that was to prove almost as startling as her vocal flights. No Jenkins recital was accompanied by less than three changes. In "Angel of Inspiration" a very substantial and matronly apparition, all wings and tinsel and tulle, made its way through potted palms to the curve of the grand piano. Small wonder the late Helen Hokinson was an ardent Jenkins fan.

Her method of ticket distribution was also unique and a model of straightforward dealing. In the hands of the scalpers those coveted pasteboards would have brought ten times the price. It is doubtful, however, if this was the reason she insisted on personal application to the genteel midtown hotel where she had rooms. Toying with the tickets as Rosina might with her fan she would inquire:

"Mr. Gilkey, are you a--a newspaperman?"

"No. Madame Jenkins," the applicant replied quite soberly, "a music-lover."

"Very well," the diva beamed. "Two-fifty each, please. Now would you like some sherry?"

Would he? Who wouldn't sit down for a friendly glass with this phenomenon in the musical life of our time?

It is too bad she did not record her favorite encore, Clavelitos, a number she invariably had to repeat. A contemporary account describes Madame Jenkins as appearing in a Spanish shawl, with a jeweled comb and, like Carmen, a red bloom in her hair. She punctuated the rhythmic cadences of the song by tossing tiny red flowers from her pretty basket to her delighted hearers. On one occasion the basket in a moment of confusion followed the little blossoms into the audience. It too, was received with spirit.

Before she would do the repeat her already overworked accompanist had to pass among the jubilant groundlings and retrieve the prop buds and basket. The enthusiasm of the audience at this point reached a peak that beggars description.

After a taxicab crash in 1943 she found she could sing "a higher F than ever before." Instead of a lawsuit against the taxicab company, she sent the driver a box of expensive cigars.

Although high coloratura was Madame Jenkins' particular province, she also ventured into the quieter realm of lieder. She opened her 1934 program with Die Mainacht of Brahms. Under the title was this quote:

O singer, if thou canst not dream, Leave this song unsung.

Nobody will ever say Florence Foster Jenkins couldn't dream.

For some time there has been wide demand for a reissue of this Florence Foster Jenkins album, but it was felt that an attraction should be found to couple with the soprano's recordings.

If it is impossible to predict where the lightning of genius is going to strike, how much less predictable is the urge to artistic endeavor. One day with no advance warning whatever Jenny Williams and Thomas Burns walked into RCA Victor's Custom Record Department. The records they wanted to make were to be for their own use but eventually they agreed to the public issuance of the material on this disc. The English translations are their own and speak for themselves - also for the cause of opera in English.

As Madame Jenkins found her way to the recording studios from the concert hall, perhaps Miss Williams and Mr. Burns, with the start they may surely expect from this disc, will one day attempt to fill, in a measure, the gap left by Madame Jenkins' departure from the musical scene.

Francis Robinson

Assistant Manager of the Metropolitan Opera (1952-76)

and author of "Caruso: His Life in Pictures "

Florence Foster Jenkins The Diva of Din by Daniel Dixon

IN THE FALL of 1944, it was announced that Florence Foster Jenkins was to lift her voice in song

IN THE FALL of 1944, it was announced that Florence Foster Jenkins was to lift her voice in song

from the hallowed stage of Carnegie Hall in New York. Immediately the world of music was seized by a rare excitement. The concert was sold out for weeks in advance, with tickets scalped for as much as $20 apiece.

Madame Jenkins' recital was the incredible climax of a bizarre career. For Madame Jenkins' shortcomings as an artiste were nothing short of awesome. A dumpy coloratura soprano, her voice was not even mediocre - it was preposterous! She clucked and squawked, trumpeted and quavered. She couldn't carry a tune. Her sense of rhythm was uncertain. In the treacherous upper registers, her voice often vanished into thin air, leaving an audience with its ear cocked for notes with which she might just as well have never taxed her throat. One critic dolefully described her as "the first lady of the sliding scale." Peevishly remarked another: "She sounds like a cuckoo in its cups."

Such tart comments were heaped upon Madame Jenkins throughout the 30-odd years that she performed in public. Yet throughout them she was immensely popular among her colleagues. Many of the world's most distinguished musicians- Enrico Caruso for one-regarded her with affection and respect. Audiences laughed at her - laughed until the tears rolled down their cheeks, laughed until they stuffed handkerchiefs in their mouths to stifle the mirth - but she was never dismayed. Even when a song was punctured by rowdy applause (her listeners sometimes responded to a piercing clinker with whoops of "Bravo! Bravo!") the diva simply smiled and bowed. After all, she modestly murmured, didn't Frank Sinatra arouse the same sort of buoyant enthusiasm among his adoring bobby soxers?

However meagerly endowed she may have been in voice, Madame Jenkins was a truly remarkable woman. She was born Florence Foster, the daughter of a starchy Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, banker. As was customary for young girls of her station in those culture-conscious Victorian times, she was given music lessons. Her career was launched at the age of eight with a piano recital in Philadelphia. At 17, she announced her wish to go abroad and take up music as a profession. But Father Foster was one of those heavy handed gentlemen who believed that a woman belonged at home, surrounded by teacups and servants, embroideries and children. He declined to foot the bills.

Florence had an answer to that. She eloped to Philadelphia with Frank Thornton Jenkins, a young doctor. But it was an unhappy marriage and divorce came in 1902. Cut off by her unyielding father, Florence scratched out a precarious living as a teacher and pianist. In 1909, Father Foster passed away. He had relented, it turned out, and left Madame Jenkins a comfortable estate. With that, her career began in earnest. "Her singing instructor," said St. Clair Bayfield, who acted as her manager for over 36 years, "was a great opera star. But there is only one person in the world" he pointed to himself "who knows the name."

In 1912, at her own expense, Madame staged her maiden concert. At the start, she performed exclusively in such favored cities as Newport, Washington, Boston and Saratoga Springs. Soon she had gathered about her a devoutly loyal cluster of tone-deaf cluhwomen. Madame had stupendous energy. She founded, supported and presided over the Verdi Club. In addition she belonged to and frequently arranged musical benefits for many other women's organizations. In staging these affairs, Madame Jenkins proved herself a shrewd executive and a canny promoter. Most of her productions made money, perhaps because she herself was usually billed as the feature attraction. The proceeds of her private recitals were generally handed out to needy and deserving young artists, as were large chunks of her personal fortune. "She only thought," Hayfield insisted, "of making other people happy."

When Madame had attracted the notice of a few astonished critics, she decided that the time had come to set up headquarters in New York. It was here that, year by year and recital by recital, her single-minded zeal was rewarded. She became a celebrity, then a legend. Madame performed in New York at least two times a year at Sherry's on Park Avenue, and once a year she gave a private concert at the Ritz-Carleton Hotel - an event to which 0nly a select assortment of friends, admirers, colleagues and critics were invited. These appearances, one newspaper declared, were "awaited with more than the customary gusto." Upwards of 800 cheering people were crushed into the brocaded ballroom. Gatecrashers had to be herded away by the police. To Madame Jenkins, a song recital was more than a matter of music. Simply to produce what she called "pure and radiant tones" was not enough. So her audience "the lonely women and artistic men" to whom, said St. Clair Bayfield, "she afforded so much happiness" were given beauty of atmosphere as well.

The stage was invariably smothered in flowers and greenery, it being the diva's theory that their perfumes would mingle deliciously with the trills and arabesques of her voice. And, in order to call forth an even deeper response to her offerings, she made it a habit to appear in costume. One of her favorite selections, "Angel of Inspiration," brought her before the audience in tulle and tinsel, a rather pudgy apparition in sturdy golden wings, standing amid potted palms. In another of her most popular renditions, a Latin number called "Clavelitos," she rigged herself up in a vivid Spanish shawl and put a large red flower in her hair. Archly fluttering an enormous fan, she marked the rhythmic cadences of the song by strewing handful after handful of rosebuds among the audience. Once she got so worked up that she tossed not only blooms, but the basket in which they were carried, into the crowd. This caused a sensation. When her delighted listeners roared for an encore, she had an assistant hurry out front and gather up the blossoms. Then she repeated the whole routine.

No bravura was too difficult for Madame to challenge. Her programs regularly included some of the most strenuous and exacting vocal works in the musical library. In addition to Mozart and Verdi and Rachmaninoff, however, there were less demanding selections from the pen of her steadfast accompanist, Cosme McMoon, and occasionally even an air composed by herself. One of her most frequently repeated numbers was a song by Brahms, subtitled on her gilt programs: "0 singer, if thou canst not dream, leave this song unsung." At the conclusion of a concert, "flushed and happy, surrounded with flowers," she often delivered a little speech in which she invited members of the audience to write and tell her which songs they had enjoyed most. "It may not be important to you," she would say, "but it is very important to me."

As her reputation mounted, it was inevitable that Madame Jenkins should be asked to record. This she did, incomparably. And in her four immortal recordings, she adopted a highly individual approach. "Rehearsals, the niceties of pitch and volume, considerations of acoustics, all," wrote an official of the recording company, "were thrust aside by her with ease and authority. She simply sang and the disc recorded." More often than not, she would pronounce the first rough test of a song to be "excellent - virtually beyond improvement" and order all copies to be made from such primitive pressings. Only once did she betray any mis-givings. On that occasion she phoned on the day following a session to say that she felt a trifle worried about a note" at the end of an aria from "The Magic Flute," by Mozart. But The Melotone Recording Studio's director Mera M. Weinstock gracefully quieted her fears. "My dear Madame Jenkins," she said, "you need feel no anxiety about any single note."

She didn't. She had a superb faith in her destiny as a diva - a faith so staunch and unswerving that it plugged her ears to the sour notes of the truth. "When it came to singing,"accompanist McMoon once explained, "she forgot everything. Nothing could stop her. She thought that she was a great artist." Shyly, but firmly, she informed a Melotone executive that she had listened to a certain aria from "The Magic Flute" as recorded by famed prima donnas Hempel and Tetrazzini, and that her own rendition was "beyond doubt the most outstanding of the three."

To Madame Jenkins, criticism sounded like kudos, ridicule like acclaim. Praise was detected on the lips of the most unsympathetic reviewers. Those whose remarks were uncompromisingly harsh were either  shrugged off with queenly disdain or denounced as unlettered louts. "They are so ignorant, ignorant!" she once burst out. When, as sometimes happened, the laughter of her audience grew so raucous that it would no longer be all overlooked, she simply ascribed the boorish behavior to "professional jealousy" or to "those hoodlums." The hoodlums were, of course, her "spiteful enemies." It was self-deception carried to outlandish extremes - but it was harmless and gentle and, in its own weird way, magnificent. Only once was her confidence observed to falter. On that occasion she told a friend, "Some may say that I couldn't sing, but no one can say that I didn't sing."

shrugged off with queenly disdain or denounced as unlettered louts. "They are so ignorant, ignorant!" she once burst out. When, as sometimes happened, the laughter of her audience grew so raucous that it would no longer be all overlooked, she simply ascribed the boorish behavior to "professional jealousy" or to "those hoodlums." The hoodlums were, of course, her "spiteful enemies." It was self-deception carried to outlandish extremes - but it was harmless and gentle and, in its own weird way, magnificent. Only once was her confidence observed to falter. On that occasion she told a friend, "Some may say that I couldn't sing, but no one can say that I didn't sing."

Without question, Madame Jenkins was a star. That she was touched with a gentle madness made no difference. For she had the unfathomable glint and glitter about her that, wherever encountered, divides the unique from the ordinary. Whether by intention or by accident, she was an inspired show-man. Bayfield once said of her: "You know, on a stage a person will sometimes draw the attention of a whole audience. There's something about her personality that makes everyone look at her with relish. That's what Mrs. Jenkins had. You could feel it in the applause. That's why she drew such enormous audiences to her concerts with very little instrument in voice. People may have laughed at her singing, but the applause was real."

For years her admirers urged Madame Jenkins to make an appearance at Carnegie Hall. And for years she resisted such suggestions. Why? Nobody knows, exactly. But in 1944 she was 76 and there might not be many chances left. So the momentous arrangements were made. And on October 25th, the concert took place, with 2,000 bitterly disappointed customers turned away. It was, of course, a thundering commercial success. As always, Madame's singing was an irresistible burlesque. She cos-tumed herself as the "Angel of Inspiration" and, complete to the abandoned tossing of rosebuds, offered the stylish gathering her rendition of "Clavelitos." Unable to contain itself, the audience clutched at its sides in agonies of mirth. The critics simply winced.

The next morning's reviews were dutifully severe. They reported, for instance, that "she was undaunted by . . . the composer's intent," that "her singing was hopelessly lacking in semblance of pitch," and that "only Mrs. Jenkins has perfected the art of giving added zest by improvising quarter tones, either above or below the original notes." Yet, on the whole, the accounts were remarkably gentle. Most of the critics discreetly refrained from any elaboration of the diva's most grievous defects. "Everybody," one reviewer volunteered, "had a pleasant evening." Wrote another: "Her attitude was at all times that of a singer who performed her task to the best of her ability." Another discerned "a certain poignancy in her delivery." Robert Bager of the New York World-Telegram observed: "She was exceedingly happy in her work. It is a pity so few artists are. And her happiness was communicated as if by magic to her listeners . . . who were stimulated to the point of audible cheering, even joyous laughter and ecstasy by the inimitable singing."

It was a typical reaction. Though most people viewed Madame Jenkins as an amusing oddity, their mirth was very often mingled with respect. For there was a quaint nobility about this woman that quelled derision and softened ridicule. She was tireless. She was genuine. And she was indomitable. Neither she nor the vision to which she clung could be squelched. More than anything else, it was this that moved the sympathy and stirred the understanding of her listeners. She became the comic symbol of the longing for grace and beauty that is in some way shared by everyone who is clumsy and shy and ill-favored. In the end, after all the laughter, Madame Jenkins was more than a joke. She was also an eloquent lesson in fidelity and courage.

That concert was her last public appearance. The effort and excitement was too much and she fell ill. But she was content. Her mission was fulfilled. On November 26th, just one month after her final triumph at Carnegie Hall, the voice of Florence Foster Jenkins was stilled forever.

Thanks to John E. Smith for generously providing a copy of this article, which originally appeared in the December 1957 issue of Coronet.

**The Relative Disappearance of Florence Foster Jenkins, or "America's First Idol"

by Sarah Brinkley

Graduate Student--Music Department

University of Central Missouri - 2011

The Relative Disappearance of Florence Foster Jenkins, or "America's First Idol"

A mainstay of solo performance in American music is Carnegie Hall. In the annals of historical performance at Carnegie Hall there have been hundreds of notable solo concerts. From Rachmaninoff in 1909, Marian Anderson in 1928, The Beatles in 1964, to Gustavo Dudamel in 2007, Carnegie Hall has had a varied and exciting history. In the aforementioned website, however, there is one solo performance missing. This performer sold old the hall in 1945 and yet most scholarly journals and references about Carnegie Hall fail to mention this performer. Soprano Florence Foster Jenkins is this singer who audiences flocked to hear. Why then, if Jenkins gave a concert to a sold-out crowd, has she disappeared from all records? Perhaps this is because she is the singer Carnegie Hall wishes to forget.

Florence Foster Jenkins was born Narcissa Florence Foster July 19, 1868 to Charles Dorrance Foster and Mary Jane Hoagland.The prestigious Wilkes-Barre family instilled the love and importance of music in their daughter from a young age. She began piano lessons and was exceptional, some may say a child prodigy. At the age of seventeen, she longed to study music overseas and make a grand tour.Her father would have nothing to do with the European tour. In retaliation, she eloped with Frank Thornton Jenkins, a notable doctor, and they lived in Philadelphia in 1885. The marriage lasted nearly as long as their courtship, however, and the couple divorced in 1902.

After her divorce, Jenkins was left nearly destitute. She taught music lessons to get by, and often performed as a pianist at society luncheons. Jenkins earned her own living in this manner for six years. In 1909 Jenkins' father died and she inherited his entire fortune. Free of the restrictions of her father and her former husband, Jenkins was free to pursue her life's goals and on her own timeline. She met a man by the name of St. Clair Bayfield and they were smitten. The two moved in together and began a romantic and business relationship that would continue until Jenkins' death.

Under Bayfield's watchful eye, Jenkins began to study voice. Her primary instructor was a maestro with the Metropolitan Opera named Carlo Edwards. In 1912, Jenkins performed her first solo vocal concert at her own expense. She enjoyed the event so much that she continued to perform in other venues. Jenkins performed small concerts in Newport, Washington, Boston and Saratoga Springs. As her popularity grew, the need for a better accompanist did as well. In 1928 Jenkins hired pianist Edwin McArthur. They worked together in concert for six years until he was ultimately fired for laughing during one of her numbers. Eventually Jenkins hired Cosme McMoon, a talent pianist and composer. He played piano and composed music for her recitals until her death. McMoon had staying power not only from his talent, but because he could keep a straight face during Jenkins' outrageous performances. It can also be noted that during the time of McMoon's employment Jenkins worked with an accompanist named William J. Cowdrey for an event in Newport in 1939. It has been thought that McMoon was the exclusive accompanist for Jenkins, however this is not the case.

Jenkins' popularity grew as word about her uncommon talent spread across New York. She kept her concerts small, performing at the St. Regis, Sherry-Netherland and Ritz-Carlton hotels in Manhattan. She often performed with a chamber ensemble called the Pascarella Chamber Music Society, a group that would accompany her along with Cosme McMoon. Although the audiences were small in number her concerts always netted a profit. Jenkins still had the majority of her father's fortune to spend, so she gave the majority of her concert earnings to young artists as well as those in need. It was at this time that Jenkins' repertoire expanded to include the songs that she is most remembered for today.

Jenkins' set list included "Vissi d'arte," "Mein herr, Marquis," or "Adele's Laughing Song," and Lakmé's bell song. Her signature number, however, was Mozart's "Der Hölle Rache," or "The Queen of the Night" aria. When Jenkins would perform these arias audiences would find it nearly impossible to keep composure. Most would stuff handkerchiefs into their mouths or cough quietly during the number. When the song was over, the audience would let loose with a roar of applause, finally able to burst out laughing as they were unable to do before. More often than not they would implore her for an encore. Jenkins most favorite encore selection was "Clavelitos," which brought the audience more delight.

To add to the eccentricities of her voice, Jenkins performed in costume. She would don a shepherdess outfit, an 19th century hoopskirt, or her favorite costume, a long silvery gown complete with an oversized pair of wings. In this ensemble she usually sang the piece "Angel of Inspiration" and audiences went wild. For the encore "Clavelitos," Jenkins would change her dress entirely to meet the song's Spanish flair. She would emerge from backstage dressed as a Spanish señorita, shawl covering her shoulders and carnations in her hair. During the piece she would throw roses at the audience, and afterward her dutiful accompanist McMoon would scoop them up, ready to be tossed again at the next performance. Jenkins' "Angel of Inspiration" costume.

To add to the eccentricities of her voice, Jenkins performed in costume. She would don a shepherdess outfit, an 19th century hoopskirt, or her favorite costume, a long silvery gown complete with an oversized pair of wings. In this ensemble she usually sang the piece "Angel of Inspiration" and audiences went wild. For the encore "Clavelitos," Jenkins would change her dress entirely to meet the song's Spanish flair. She would emerge from backstage dressed as a Spanish señorita, shawl covering her shoulders and carnations in her hair. During the piece she would throw roses at the audience, and afterward her dutiful accompanist McMoon would scoop them up, ready to be tossed again at the next performance. Jenkins' "Angel of Inspiration" costume.

Jenkins continued to perform her hotel salon concerts and her audiences grew into the upper hundreds. Disappointed society patrons would be turned away because the room was at capacity. Critics were invited to her concerts and reviews were scathing.

"Mrs. Jenkins appeared in flame-colored velvet, with yellow ringlets piled high on her head. For a starter she piced Brahms' Die Mainacht, subtitled on her gilt program as 'O singer, if thou canst not dream, leave this song unsung.' With her hands clasped to her heart she passed on to Vergebliches Standchen, which she had labeled 'The Serenade in Vain.' "

The week of June 9, 1941 marked a new direction for Jenkins. She stepped into Melotone Recording Studio in Manhattan to record her voice. Jenkins chose to record her signature aria, "Der Hölle Rache," and sell it to her friends at the sum of $2.50 per copy. Where she sang in her concerts with the usual gusto and vim, this recording session proved different. She seemed to doubt herself and the manner in which she sung. Following her recording session, Jenkins called the recording studio because "she felt trifle worried about a note" at the end of her recording. The director of the studio quelled her fears and told her that she "need feel no anxiety about any single note."

Near the end of her career, Jenkins was persuaded to make an appearance singing at Carnegie Hall. At the age of 76, although she claimed to be much younger, preparations were made for her concert on October 25, 1944. She would sing her normal concert program, complete with costume changes and encores if necessary. Advertisements were put out in the New York Times, "Carnegie Hall has been completely sold out for the recital to be given there tomorrow night by Florence Foster Jenkins, soprano, assisted by the Pascarella Chamber Music Society." Upon arrival at the hall, the scene was chaos. Nearly 2,000 paying ticketholders were turned away in disappointment. Jenkins sang through her concert and the audience was not as kind as they were at her hotel performances. Instead of containing their laughter until the end of her pieces, they laughed openly.

The next day reviews were published in all the major papers and magazines of the area. In the Times, the concert barely received mention:

"Florence Foster Jenkins, soprano, gave a recital at Carnegie Hall last night, assisted by the Pascarella Chamber Music Society quartet; Comse McMoon, pianist, and Orest DeSevo, flutist." Other reviews were not so passive. Critics noted that the singer was "hopelessly lacking in semblance of pitch," and that she "improvised quarter notes." Robert Bager, a critic for the New York World-Telegram made more positive observations about Jenkins' performance. "She was exceedingly happy in her work...her happiness was communicated as if by magic to her listeners..."If Florence Foster Jenkins wanted nothing but to delight her audience, it seems that she may have done just that.

The Carnegie Hall event would turn out to be her last concert. A few weeks after the performance, Jenkins would suffer a heart attack from which she would never recover. Some maintain that it was the terrible reviews that weighed on her heart, but friends knew better. Close friend an assistant manager at the Met Francis Robinson claimed she died with a "happy heart." She died with her confidant St. Clair Bayfield by her side in her Manhattan apartment on November 26, 1944. Her services were held at Frank E. Campbell. "The Funeral Church," Inc. on Madison Ave.

In articles written later on Carnegie Hall, Jenkins is mentioned in passing. "Great Moments at Carnegie Hall" recalls that her "demolitions were innocent and unpremeditated," but that the "most slashing assault on music ever made in Carnegie Hall" was Vladimir Horowitz and Sir Thomas Beecham with the Philharmonic. When the hall turned 90 years old, Jenkins received another mention. "...the deliriously happy audience was privileged to hear the worst coloratura soprano in history. She laughed all the way to the bank." After these two articles, however, Jenkins has lost all recognition from Carnegie Hall. Even though she sold out the hall, despite the fact she rented the hall for her own performance, the recognition should still be met.

Possibly the greatest compliment to come to Florence Foster Jenkins is the two play written about her life. Souvenir, written by Stephen Temperley, opened in New York off-Broadway and won several awards, including a Tony for Best Actress Judy Kaye as Florence.The play is a running dialogue between Jenkins and McMoon as she prepares for her Carnegie Hall recital and ends with her death. The actress is charged with the unseemly task of singing like Jenkins for the run of the show, and then in the finale to sing a flawless "Ave Maria" as Jenkins would have heard in her head. The play's title is thought to come from the only "souvenir" from her first marriage, a case of syphilis. The show is still running off-Broadway and has made a successful American tour.

It is interesting to wonder what would have happened to Jenkins had she performed her concert in the current age. With the social media present, it is almost certain that she would have been present on YouTube, and she may have even been a contestant on "American Idol" or one of its sister programs. Americans have a strange level of Schadenfreude (satisfaction or pleasure felt at someone else's misfortune,) when it comes to singing competitions.

Something akin to Jenkins' Carnegie Hall event happened to a German contestant of the equivalent of "American Idol." Menderes Bagci performed Usher's "U Remind Me" and was laughed at by the judges. Despite the criticism, Bagci came back for every subsequent season of "Idol" and his cult status among viewers grew. This seems like what was happening in Jenkins' life with her performances. Even though her critics laughed in her face and called her talentless, she continued to perform and gained celebrity status.

One of Jenkins' most famous quotes is "Some may say that I couldn't sing, but no one can say that I didn't sing." Many people today sing in the shower, in the car, or refuse to sing because they fear what others will think of their voices. Florence Foster Jenkins defied convention and sang simply because she felt like it. She sang for her friends, she sang for famous composers, she sang for great patrons of society, and they all paid to hear her sing. Jenkins had the nerve to study the music that she desired, although it easy to study what one wants when one is wealthy. Even though she was not a good singer, her presence must still be acknowledged in the history of American music. Simply because one is "bad" does not mean that one can be shut out and forgotten. It is time to give Lady Florence, (as she liked to be called,) her great, (or not so great,) place among the singers in American music.

Bibliography

http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/schadenfreude

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Florence\_Foster\_Jenkins

http://www.carnegiehall.org/History/Timeline/

http://www.maxbass.com/Florence-Foster-Jenkins.htm

http://www.souvenironbroadway.com

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,847374,00.html

http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,765744,00.html

Hellmueller, Lea C. and Nina Aeschbacher. "Media and Celebrity: Production and Consumption of 'Well-Knownness'." Communication Research Trends 29, no. 4 (2010): 3-35.

"Florence F. Jenkins in Recital." New York Times, October 26, 1944.

Millstein, Gilbert. "Great Moments at Carnegie Hall." New York Times, May 22, 1960.

"Music Notes." New York Times, October 24, 1944.

"Music Notes." New York Times, October 25, 1944.

"Obituary 1." New York Times, November 28, 1944.

Peters, Brooks. "Florence Nightingale: Brooks Peters Tells the Story of the Legendary Florence Foster Jenkins, A Soprano Without Peer" Opera News 65, no. 12 (June 2001): 20-23.

"Programs of the Week." New York Times, November 4, 1934.

Bibliography (continued)

Schonberg, Harold C. "Carnegie Hall, at 90, Is Thinking Young." New York Times, June 29, 1980.

Stearns, David Patrick. "That (ugh) voice! Tale of Florence Foster Jenkins." The Philadelphia Inquirer, January 23, 2008.

"Social Activities in New York and Elsewhere." New York Times, September 8, 1939.