Thameside Molesey - Hurst Park (original) (raw)

After the closure of the old race-course the district was rife with speculation as to the future use of the site. The land was on lease to Mr John Taylor, of Manor Farm, West Molesey, but was owned by absentee lords of the manor; and it was the generally held opinion that they would immediately sell the estate for housing development.

However, a group of wealthy investors, who saw potential for the formation of one of the new 'park' type race-courses, banded together to form a syndicate to acquire the land and so to lay it out.

The interests of this company were more speculative than sportive. They had invested money with the object of making a profit and, if capital had to he spent on bringing the ground up to racing standards, patrons would have to pay to attend the meetings. No longer would the course be open to all and sundry. This meant, of course, enclosing the whole site within a fence, a requirement which was partially obstructed by virtue of an old road, originally running directly from the village of West Molesey to Hampton Ferry, the lower end of which had been diverted many years before the 'New Road' had been substituted; the upper end still traversed diagonally across the Hurst.

Application was made to West Molesey Parish Vestry — which was at that time the authority for local government in the area — for permission to divert the road to a different alignment. The request was backed up with the threat that, if such sanction was not forthcoming, there would be no race-course, and if there was no race-course the land would be sold for housing. Faced with such intimidation the parish had little choice but to allow the change to take place. At a vestry meeting held on 14 February 1889, with the Vicar, Rev T.G. Nicholas, in the chair, authority was granted to 'divert, stop-up, and turn' the old road, and to substitute a new carriageway of the width of forty feet and a length of about two thousand six hundred feet. This is, of course, the present Ferry Road, although it has since been truncated by posts erected across the road by the towpath.

There were some protests against the stopping-up of the old road, mainly from certain gentlemen living in East Molesey who had lost their short cut across the Hurst to the ferry; but the action was defended on the ground that the estate would be 'utilised in a manner that will at any rate preserve it from spoliation at the hands of the jerry builder'.

During the next few months gangs of workmen arrived on the Hurst, laying down the new road, levelling the site, constructing the stands, stables, and rings, raising the fence, and supplying 'every convenience for sporting purposes

It was this huge, all encompassing fence, seven feet high of close-boarded timber tarred over, which caused the most consternation. The residents of Hampton were particularly outraged that the view from Bell Hill, which previously had a pleasant prospect over the open Hurst, was now blighted by this obnoxious palisade and the vast new stands and other buildings.

The course, which was to be called Hurst Park, was intended to be run as a club, similar to the other park-type courses first started at Sandown in 1875. With a Members' Enclosure, access to which was restricted to members of the club and their properly vetted friends only, others would be restricted to the public stands and park.

However, the enterprise was not to be limited to horse racing only, but was intended to be a grand, general recreative venture, a sort of country club, to which end they also purchased the old mansion known as Hurst House, which stood in about sixteen acres of its own grounds, adjacent to the Hurst, on the corner of Hurst and New Roads, and which had been unoccupied for some seventeen years. As can well be imagined the house was then in a much run-down and dilapidated condition, and considerable capital had to be expended on bringing the building up to the state required for service as a private club-house. Stables were erected in the grounds for the accommodation of those members who preferred to drive down in their own carriages, and a dock, or marina as it would now be called, was cut from the Thames for the benefit of those who favoured the more leisurely journey by river.

It was intended, in fact, to be somewhat similar to Tagg's Club, with the added attraction of racing thrown in. The races were to be not only with the horses but with ponies, galloways, and trotting as well. Other sports were to be catered for by the laying down of polo grounds, tennis courts, and a cricket pitch, and the club-house was to be kept open for the delectation of members at all times. By January 1890 it was reported that the club had upwards of one thousand six hundred members, and that the club-house would be opened in a week or two.

As the race-course itself was rather short, being only a little over half-a-mile in length (the original Hurst, it must be remembered, lay only in West Molesey parish, and finished opposite the end of Hurst Lane), all the races had to be run over a round course; in default of a long, straight, sprinting run the Jockey Club would not issue a licence for flat racing. It was intended, therefore, to provide only hurdling and steeplechases for horses, and pony and galloway races outside the jumping season.

The course was opened for the first national hunt meeting on 19 March 1890, amid hails of great excitement. The Times newspaper declaimed: 'At present few even of its most constant habitues would recognise in Hurst Park the old Hampton racecourse and meadow, so completely have the aspects and surroundings been changed and beautified under the supervision of the Hurst Park club'.

The Surrey Comet told a similar story: 'On Wednesday morning, East Molesey and Hampton Court awoke to a scene of bustle and excitement, which recalled the long-faded glories of 'Appy 'Ampton, where the London coster and his friends abandoned themselves to the pleasures of the turf and periodical race meetings on the old Hurst. The occasion of this unwonted activity was the inaugural fixture of the Hurst Park Club. Amongst the earliest arrivals were race horses and a strong body of police. Seven special trains brought their freights of sporting men from Waterloo to Hampton Court Station, and two specials were reserved for members of the club. It is computed that over 2,000 people arrived by these trains. Large numbers of the patrons of the turf, however, preferred to travel by road. City omnibuses well laden arrived at intervals, and the familiar hansom, together with a continual stream of private conveyances and carriages of all descriptions, poured in their contribution from all parts'.

The first in what was anticipated to be a long run of pony meetings was held a month later, but the hopes of the promoters came nowhere towards fulfilment. Pony racing did not draw the crowds — they just stayed away.

In the event the whole enterprise turned rapidly into one vast belly-flop. There were losses on all later meetings except one — and that made a net profit of but £28 6s 11d. The total cost of setting up the club and laying out the course had amounted to nearly thirty-nine thousand pounds, the lease costing nine hundred pounds a year, and the deficiency on the first twelve months' trading reached almost two thousand three hundred pounds.

The cricket ground, it is true, had been opened in September 1890 with a much heralded match between the club, fortified by the addition of some well-known cricketing names, and the visiting Australian Test Team. It was complained that the pitch was not quite ready, and not up to the standard expected for first-class play. 'A fair company witnessed the day's play', but it was far too late in the season for this to have any effect on the overall financial fortunes of the club.

It was decided, therefore, to give up the pony and galloway racing as a dismal failure, and the social club had no hope of success without the racing, as it was seldom used except during meetings.

The only hope of retrieving the diminishing situation lay in procuring extra land, over and above the ninety-three acres of the old Hurst already held, to lengthen the course, in the expectancy of receiving a licence to hold flat-race meetings, and to present a good programme, with prizes sufficient to attract high-class fields, and trust thereby to break into the existing calendar.

Negotiations were concluded with Mr Kent to acquire a number of meadows at the eastern end, between the Hurst and Molesey Lock, on a twenty-one year lease at a rent of four hundred pounds per annum. These were levelled and laid out as a straight 'mile' course (although in fact, it was only seven furlongs), and new turnstiles were added.

The necessary licence was successfully obtained and flat racing commenced on 25 March in 1891, after which, for the next seventy-two years — except for the hiatuses of two world wars — success came and fortune flourished, so much so that in three years the syndicate were able to purchase the freehold at a cost of some seventy-five thousand pounds. The capital for that was raised by the issue of four per cent debenture stock, in one pound shares.

Hurst Park burst fitfully into international prominence in June 1913, as the scene of one of the more outrageous exploits of the women's suffrage movement. The 'Votes for Women' campaign, which had gained an ever increasing tempo, had by this time reached a crescendo of open warfare, culminating in an eruption of window-smashing, incendiarism, and destruction of public and private property of all kinds.

During the running of that year's Derby, Mrs Emily Davidson had tried to unseat the jockey from the King's horse, an attempt which had caused her to be badly trampled beneath the beast's hooves, and to receive such gruesome injuries that she died the following Sunday, 8 June.

The fatal news soon spread, and the authorities expected some sort of holy war of attrition to take place, but probably never anticipated a reaction either so swift or so violent.

Shortly after midnight a passing constable on cycle patrol along Hurst Road observed a glow emanating from near the grandstand, which almost immediately burst into a mass of flames. The Molesey Fire Brigade was summoned, and arrived with its steam pump within a few minutes, by which time the buildings, being constructed mainly of timber, were well engulfed in the blaze. Before long, neighbouring brigades also arrived — Kingston, Surbiton, Hampton, Hampton Hill and the Metropolitan Water Board. At one time the flames reached such a height that they could be seen as far away as Carshalton, and it lit the sky there so brilliantly that the local fire brigade turned out thinking the blaze was in their own district.

The firemen played the flames for some three hectic hours, pumping water from the Thames, before the conflagration was finally subdued. Came the daylight and the damage could be fully assessed. The main stand ended as 'a fantastic medley of charred wood, twisted iron, broken and melted glass, and gaunt fire-scorched pillars of brick'. The other buildings gutted included the member's and Tattershall's stands, the kitchens and dining rooms.

The Royal box and grandstand, after the suffragette arson attack, June 1913.

The initial cause of the blaze was soon established when a placard proclaiming 'Give the Women the franchise', and a quantity of suffragette literature were discovered.

Shortly afterwards two ladies were arrested at Richmond, and were charged before the magistrates at Kingston with being concerned together in feloniously and maliciously setting fire to the buildings and causing damage to the extent of £7,000. They were Clara Giveen (aged 26), a woman of independent means, and Kitty Marion (35), a music hall artiste. Both had seen the inside of prison before.

Of these two ladies, undoubtedly Kitty Marion is the better known. The younger girl, although an organiser for the Womens Political and Social Union, seems to have been shielded from some of the rigours of prison convictions by the efforts of influential friends.

Miss Marion, however, came from a much different background, and was much differently treated by the authorities. She had been born in Germany, but came to Britain to escape a tyrannous father, and joined the theatrical profession, treading usually on the boards of provincial music halls and variety theatre. She appears to have been as passionate and impulsive as her mop of violent red hair would betoken. Having been imprisoned as early as 1909 for breaking windows in Newcastle when Lloyd George went to visit Tyneside, she went on hunger strike, and resisted forcible feeding with intense vigour. Barricading her cell door with furniture, she kept the staff at bay until the next day when they managed to chisel the hinges away. On another occasion, when all metal objects had been removed from her reach, she broke open the pillow with her teeth, scattered the contents around, tore up the prison bible, and in the middle of the night, by breaking the glass of the gaslight, managed to set fire to the accumulation. By the time the smouldering combustion was detected and dowsed, the inmate was already in an insensible condition, and in her already weak state, was stimulated only after the employment of much effort.

At the opening of the Welsh National Eisteddfod in 1911, with some colleagues, she again tried to interrupt Lloyd George, but was roughly thrown out by the stewards, and set upon by the crowds, who fell on them, tore off their clothes, and snatched out lumps of hair. 'Being thrown to wild beasts', she afterwards declared, 'is nothing to being thrown to an infuriated mob. The former may tear you to pieces, but would draw the line at indecent assault'.

The two were committed to appear at the Surrey Assizes at Guildford, found guilty, and each sentenced to three years' penal servitude.

Of Clara Giveen little seems to have been heard of since, but Kitty Marion still kept her name and her cause in the public eye. She immediately went on hunger strike and, because of her weak condition, was released under the terms of the so-called 'Cat and Mouse Act'. She went straight round to the Home Office and threw a stone through a window, in protest at her release, for which she was again arrested, again sent to prison, again refused to eat, again released, and in an emaciated state taken to a nursing home. After serving four and a half months of her sentence she was finally discharged.

By this time rumblings of war with Germany were being heard and, because of her teutonic origins, Miss Marion decided to emigrate and went to live in the United States, where she eventually took American citizenship.

Such a fiery personality could not, of course, exist without giving her support to some under-dog and well-deserved undertaking so, still in the forefront of women's liberation, she threw herself into the birth control movement. Once again she was in the van of a crusading protest. For thirteen years she stood every day on the streets of midtown New York selling birth control literature, facing countless jeers with typical defiance and equanimity, and again being arrested many times. When the work came to an end in 1930 the American Birth Control League presented her with a cheque for five hundred dollars, and gave a grand luncheon in the Town Hall in her honour. She finally died in 1944.

The self-same war clouds which sent Kitty Marion scurrying off to America also brought changes to Hurst Park. The fire-ravaged stands were hastily rebuilt, but hostilities meant the cessation of racing for the duration. The park, however, fulfilled its duty in the service of the nation, as a training airfield for the Royal Flying Corps and the nascent RAF. It was again to house troops, both British and American, during the second struggle some twenty-five years later.

During the inter-war years and afterwards many improvements were made to the course and its facilities. The old Tattershall's stand was demolished, and replaced by a magnificent new one at a cost of £35,000; totalisators were added (among the first in the country), and photo-finish equipment installed, making Hurst Park not only one of the most up-to-date but one of the most intimate and friendly courses in the kingdom. As many as 50,000 individuals swarmed down (principally by the special trains — four shillings return including entrance to the course) on Whit-Monday, the most popular meeting in the calendar.

By 1960 rumours began to circulate that the end of Hurst Park was in sight. It was still a popular venue, meetings were well attended, and it was making a profit. But for the proprietors it was a business venture, and more money was to be obtained from property development than from horse racing, so the blow was struck. Application was made to build houses on the site and, in spite of a spirited opposition put up by Molesey people, planning permission was granted.

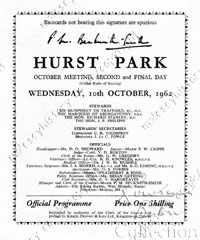

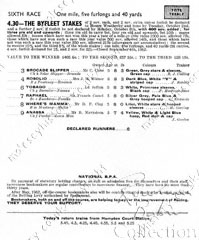

On Wednesday 10 October 1962, at 4.30 pm, a chesnut named Anassa, the favourite at 11-8, won the Byfleet Stakes, the last race ever to be run on this once classic course. One London bookmaker (and bookies are not normally noted for sentimentality), hung a funeral wreath of chrysanthemums around the winning post, bearing a card with the simple message: 'With sincere memories of a friendly racecourse from all racegoers'. The donor bemoaned: 'This is a sad day for me. Mind you I've never won much money — here as elsewhere — but it was such a happy course'.

Happy course or not, in the sacred fulfilment of producing the most profit for its shareholders, it had to go. Soon the auctioneer started to bang his gavel; acres of the verdant turf — noted for its springiness over a hundred and fifty years before - was knocked down to Royal Ascot; the largest stand — over 95 yards long — went to Mansfield Town Football Club, and the railings to a dog track. Everything from starting gates to park benches, number boards to paving stones, the fire engine to ladies' loos; altogether some six hundred and sixty-five lots were sold to the highest bidder, bringing in about ten thousand pounds. Thus ended the centuries' long sportive associations of Molesey Hurst.

Horses leave the paddock at Hurst Park.

Kitty Marion of the women's movement.

Sir Winston Churchill joins the members in their enclosure at Hurst Park.

The 1949 Act to close part of Ferry Road.

The last day's racing at Hurst Park — 10 October 1962 (and below, the last race).

The last day's racing at Hurst Park — 10 October 1962 (and below, the last race).

The sale of Hurst Park Racecourse equipment, 6/7 November 1962.

The sale of Hurst Park Racecourse equipment, 6/7 November 1962.

The Royal Flying Corps at Hurst Park in 1915.

All books copyright © R G M Baker, all rights reserved.

Images © 2006 M J Baker and S A Baker, all rights reserved.

Web page design © 2006 M J Baker and S A Baker, all rights reserved.