Understanding and Modeling the Super-spreading Events of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Outbreak in Korea (original) (raw)

Super-spreading events (SSE) have been reported for many infectious disease outbreaks such as measles [1], tuberculosis [2], Ebola [3], and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [4,5,6]. The SARS outbreaks in Singapore, Hong Kong, and China in 2003 particularly made the importance of SSE evident in understanding transmission dynamics, predicting models, and containing outbreaks. However, the criteria of SSE and their effects on outbreak control measures are still unclear. Though there is an arbitrary definition for SSE [5,6], there is no consistent and generally accepted definition yet [7].

Lloyd-Smith et al. introduced ν, the individual reproductive number, which is the expected number of secondary cases transmitted by a particular primary case, to explain a SSE with epidemiological modeling and successfully show that SSE are not exceptional events, but are "normal features of disease spread" as observed from the right-hand tail of a distribution of ν [7]. In a traditional epidemic model, the variation of ν is ignored and ν = R0 for all cases, yielding Z ~ Poisson (R0), where Z is the number of secondary infections caused by each case and R0 is the basic reproductive number. Lloyd-Smith et al. generated a general model, Z ~ negative binomial (R0, k), where ν is gamma distributed with the mean R0 and dispersion parameter, k. The lesser the value of k is, the greater is the heterogeneity of ν. After fitting these models to the SARS outbreaks in Singapore and Beijing, they found that the negative binomial model was unequivocally favored over other models. For example, k in the SARS outbreak in Singapore was estimated as 0.16 with the negative binomial model, which meant that ν was highly over-dispersed; results showed that a majority of SARS cases (73%) were barely infectious (ν < 1), but a small proportion (6%) were highly infectious (ν > 8) [7]. According to their findings, an infectious disease with a large individual variation of infectiousness (ν) shows "infrequent but explosive epidemics" after the introduction of a single case. They also defined a super-spreader as any infected individual who infects more than the 99th percentile of the Poisson (R) distribution, where R is the effective reproductive number of a disease.

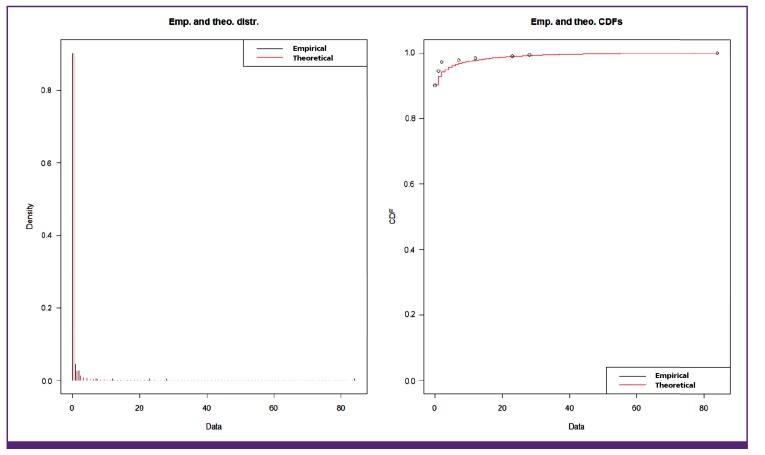

SSE also played a crucial role in the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) outbreak in Korea in 2015. The outbreak could be summarized as an explosive epidemic by infrequent super-spreaders. The number of secondary cases in the transmission tree was extremely skewed. Among 186 confirmed cases, 166 cases (89.2%) did not lead to any secondary cases, but 5 (2.7%) super-spreaders lead to 154 secondary cases. The imported index case was a super-spreader who transmitted the MERS virus to 28 people (referred to as secondary cases), and 3 of these secondary cases became super-spreaders who infected 84, 23, and 7 people, respectively. Eighty-four secondary cases resulting from a single case is one of the largest numbers observed in a SSE since the SARS outbreak in Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong Kong. None of the super-spreaders in the MERS outbreak in Korea was a healthcare worker. Fitting a negative binomial distribution to the Korean MERS data using the R statistical package provided maximum likelihood estimates of the mean basic reproductive number, R0 = 0.93 (95% CI; 0.13, 1.75), and the dispersion parameter, k = 0.03 (95% CI; 0.01, 0.04). The estimated value of k was much lesser than 1 suggesting that individual infectivity was highly over-dispersed [7]. The k value of the MERS outbreak was even lesser than that of the SARS (k = 0.16) [7] and Ebola (k = 0.18) [3] outbreaks. Fig. 1 shows the empirical and theoretical density distributions and the cumulative density function where R0 = 0.93 and k = 0.03.

Figure. 1. The empirical and theoretical density distributions and cumulative density function of the secondary cases of the Korean Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak of 2015.

Some remaining big questions include: What is the effect of SSE on predictive modeling and the public health measures used to control outbreaks? How we can identify super-spreaders and make practical models including SSE? [4,8,9]. What determines the heterogeneity of individual infectivity in a certain outbreak is unclear. Stein summarized the factors that may shape SSE as follows: host factors including physiological, behavioral, and immunological factors; pathogen factors including virulence and co-infection; and environmental factors including crowding, misdiagnosis, inter-hospital transfer, and airflow dynamics that influence the heterogeneity of infection [9]. These lists of factors may be incomplete, but they seem to explain the SSE in the Korean MERS outbreak of 2015.

The primary goal of control strategies was to reduce reproductive numbers, and the serial changes of time-dependent generational and case reproductive numbers during the MERS outbreak in Korea were estimated to evaluate the effect of counter-measures [10]. SSE added a further complication and suggested inadequacies in the traditional approach [7,8,11]. SSE played a major role in spreading infections like SARS and MERS, and the prevention and control measures for SSE should be central in controlling such outbreaks [4,7,11]. One missed super-spreader could cause a new outbreak. Lloyd-Smith et al. showed that individual-specific strategies (for example, isolation of the infected individuals) were more likely to exterminate an emerging disease than population-wide interventions such as advising an entire population to reduce the behaviors associated with transmission [7,11]. According to the model proposed by Lloyd-Smith et al., isolating infected individuals increased the heterogeneity of infectiousness and when the variation of infectiousness was large, extinction occurred rapidly [7,11]. By taking advantage of heterogeneity, control measures could be directed towards the smaller group of highly infectious cases or the high-risk groups.

Understanding of SSE is tremendously important to make prediction models and plan prevention and control strategies for outbreaks of emerging infectious diseases including MERS. We could gain a better understanding of heterogeneity parameters and their associated factors by analyzing and modeling the epidemic data of the MERS outbreak in Korea.

References

- 1.De Serres G, Markowski F, Toth E, Landry M, Auger D, Mercier M, Bélanger P, Turmel B, Arruda H, Boulianne N, Ward BJ, Skowronski DM. Largest measles epidemic in North America in a decade–Quebec, Canada, 2011: contribution of susceptibility, serendipity, and superspreading events. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:990–998. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kline SE, Hedemark LL, Davies SF. Outbreak of tuberculosis among regular patrons of a neighborhood bar. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:222–227. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Althaus CL. Ebola superspreading. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:507–508. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70135-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Yu IT, Xu P, Lee JH, Wong TW, Ooi PL, Sleigh AC. Predicting super spreading events during the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemics in Hong Kong and Singapore. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:719–728. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Severe acute respiratory syndrome-Singapore, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shen Z, Ning F, Zhou W, He X, Lin C, Chin DP, Zhu Z, Schuchat A. Superspreading SARS events, Beijing, 2003. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:256–260. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lloyd-Smith JO, Schreiber SJ, Kopp PE, Getz WM. Super-spreading and the effect of individual variation on disease emergence. Nature. 2005;438:355–359. doi: 10.1038/nature04153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.James A, Pitchford JW, Plank MJ. An event-based model of superspreading in epidemics. Proc Biol Sci. 2007;274:741–747. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stein RA. Superspreaders in infectious diseases. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15:e510–e513. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park SH, Kim WJ, Yoo JH, Choi JH. Epidemiologic parameters of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in Korea, 2015. Infect Chemother. 2016;48:108–117. doi: 10.3947/ic.2016.48.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galvani AP, May RM. Epidemiology: dimensions of superspreading. Nature. 2005;438:293–295. doi: 10.1038/438293a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]