Testing for differential abundance in mass cytometry data (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2018 Sep 25.

Published in final edited form as: Nat Methods. 2017 May 15;14(7):707–709. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4295

Abstract

When comparing biological conditions using mass cytometry data, one key challenge is to identify cellular populations that change in abundance. Here, we present a novel computational strategy for detecting these “differentially abundant” populations, by assigning cells to hyperspheres, testing for significant differences between conditions and controlling the spatial false discovery rate. The method’s performance is established using simulations and real data where it finds novel patterns of differential abundance.

Mass cytometry allows researchers to simultaneously characterise the expression of many (> 30) protein markers in each of millions of cells1. Antibodies specific to markers of interest are conjugated to heavy metal isotopes and used to stain a population of cells. Single-cell droplets are formed and vaporized to ionize the metals, and the quantity of each isotope bound to each cell is measured by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. The resolution of mass spectrometry avoids problems with spectral overlap that are frequently encountered in conventional flow cytometry with fluorescent markers. This means that more markers can be quantified for each cell, improving resolution of distinct subpopulations and enabling deep phenotyping of cellular profiles in fields such as immunology, haematopoietic development and cancer2, 3, 4, 5, 6. The ability of mass cytometry to assay more markers leads to a concomitant increase in the dimensionality of the data. This complicates the data analysis as manual gating and visual examination of biaxial plots (as commonly used in flow cytometry) are no longer feasible when multiple marker combinations have to be considered. To address this, bespoke computational tools such as SPADE7 and X-shift8 have been developed, focusing on clustering cells into biologically relevant subpopulations based on the “intensity” of each marker (i.e., the signal of the corresponding isotope in the mass spectrum) and quantifying the abundance of each subpopulation in the total cell pool. However, these approaches fail to directly address an important question of multiparameter multi-group experiments – namely, what differs between groups?

To this end, an alternative analytical strategy is to identify subpopulations that change in abundance between biological conditions9, 10. For example, certain immune compartments are enriched or depleted upon drug treatment, and the composition of cell types changes during development. Detection of these differentially abundant (DA) subpopulations is useful as it can provide insights into the cause or effect of the biological differences between conditions. Existing methods for DA analysis cluster cells from all samples into empirical subpopulations, before checking each cluster for characteristics (e.g., marker intensities or cell abundance) that differ between conditions11, 12. While intuitive, this approach is sensitive to the parametrization of the initial clustering step. Uncertainty will be introduced into the cluster definitions when the data are noisy or the cells are not clearly separated13. This is particularly relevant for markers that are expressed across a range of intensities without clear changes in cellular density at subpopulation boundaries, such as CD38 and HLA-DR to mark activated T cells or CD24 and CD38 to define plasmablasts among B cells14. Ambiguity in clustering can affect the performance of the subsequent DA analysis, e.g., if DA and non-DA subpopulations are erroneously clustered together.

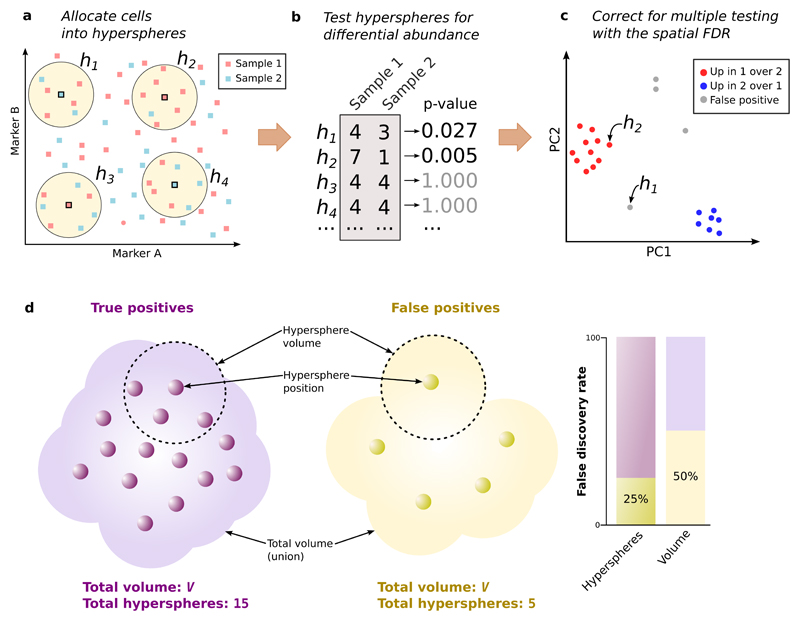

Here, we present a novel computational strategy to perform DA analyses of mass cytometry data (Figure 1) that does not rely on an initial clustering step. Firstly, we assign cells from all samples to hyperspheres in the multi-dimensional marker space. Consider a mass cytometry data set with S samples and M markers. Each cell in each sample defines a point in the _M_-dimensional space, with coordinates defined by its intensities. We consider M_-dimensional hyperspheres where each hypersphere is centred on an existing cell and has radius r=0.5√_M to offset the increasing sparsity of the data as the number of dimensions increases. All cells lying within a hypersphere are then assigned to that hypersphere. (Each cell can be counted multiple times if it is assigned to overlapping hyperspheres.) We count the number of cells from each sample assigned to each hypersphere, yielding S counts per hypersphere. For each marker, we also compute its median intensity for all cells in each hypersphere. This provides a median-based position for the hypersphere, representing a central point in _M_-dimensional space around which most of the cells in the hypersphere are located. See Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figures 1-4 and Supplementary Table 1 for more details. We also assume that marker intensities are comparable across samples – some strategies for handling sample-specific intensity shifts are described in Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Figures 5-6.

Figure 1. Schematic of the differential abundance pipeline.

(a) Cells from samples 1 or 2 are distributed across the multi-dimensional marker space (two markers shown here for simplicity). Hyperspheres (yellow, _h1_-h4) centred on selected cells are constructed, and the number of cells from each sample inside each hypersphere is counted. (b) Counts for each hypersphere are tested for significant differences between samples. This yields a _p_-value representing the evidence against the null hypothesis of no differences. (c) Multiple testing correction of hypersphere _p_-values is performed by controlling the spatial FDR. Positions of significant hyperspheres at a given spatial FDR threshold are visualized by dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA). (d) The spatial FDR is roughly equivalent to the proportion of the volume occupied by false positive hyperspheres. Each hypersphere has a median-based position (small circles) and occupies a volume of the high-dimensional space (shown as the dotted ring for two hyperspheres). The total occupied volume is the union of individual hypersphere volumes. Two groups of hyperspheres are shown – one containing true positives with genuine differences in abundance, the other containing false positives – that occupy a similar total volume V with different densities.

Next, we use the count data for each hypersphere to test for significant differences in cell abundance between conditions. The null hypothesis is that there is no change in the average counts between conditions within each hypersphere. Testing is performed with negative binomial generalized linear models (NB GLMs), which explicitly account for the discrete nature of counts; model overdispersion due to biological variability between replicate samples; and can accommodate complex experimental designs involving multiple factors and covariates. We use the NB GLM implementation in the edgeR package15, which was originally designed for analyzing read count data from RNA sequencing experiments. However, the same mathematical framework can be applied here to cell counts. In particular, edgeR uses empirical Bayes shrinkage to share information across hyperspheres. This improves estimation of the dispersion parameter in the presence of limited replicates, increasing the reliability and power of downstream inferences. (See Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Figures 7-8 for more details.) Indeed, edgeR is more powerful than the commonly used Mann-Whitney test for detecting differences in hypersphere counts in simulated data, while still controlling the type I error rate (Supplementary Figure 9).

Finally, we use the hypersphere _p_-values to control the false discovery rate (FDR) across the multi-dimensional space, i.e., the spatial FDR. To illustrate, consider the total volume occupied by the set of DA hyperspheres. (This is a union rather than a sum of the hypersphere volumes, due to overlaps between hyperspheres.) Roughly speaking, the spatial FDR can be interpreted as the proportion of this volume that is occupied by false positive hyperspheres. This is not equivalent to the FDR across the individual hyperspheres, due to the differences in the density of hyperspheres across the space. For example, the FDR across hyperspheres in Figure 1d is 25% while the spatial FDR across volume is 50%. To control the spatial FDR, each hypersphere is weighted by the reciprocal of its density (calculated in terms of the neighbouring hyperspheres). A weighted version of the Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method16 is then applied to the _p_-values and weights for all hyperspheres. If one were to split the high-dimensional space into non-overlapping partitions of equal volume, the total weight of hyperspheres within each non-empty partition would be similar, i.e., each partition of the space makes a similar contribution to the BH correction, regardless of how many hyperspheres it contains. Thus, weighting allows the FDR to be controlled across volume, rather than across hyperspheres. (See Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Figure 10 for a more precise description of the spatial FDR.) We demonstrate that our weighting scheme successfully controls the spatial FDR in simulated data, whereas a naïve approach without weighting does not (Supplementary Figure 11).

Several options are available for examining DA hyperspheres after the statistical analysis. We can identify significant hyperspheres that are not redundant to – i.e., do not lie within a certain distance of – hyperspheres with smaller _p_-values (Supplementary Note 5). The resulting subset of hyperspheres is small enough for detailed inspection of the marker intensities with a graphical interface (Supplementary Figure 12) to characterise each hypersphere. A complementary approach is to perform dimensionality reduction on the positions of the putative DA hyperspheres, yielding a low-dimensional representation of the differential subspaces for plotting. The plot is annotated based on examination of the marker intensities, incorporating biological expertise on the relationships between specific markers and cell types. This allows identification of biologically relevant subpopulations from the DA hyperspheres.

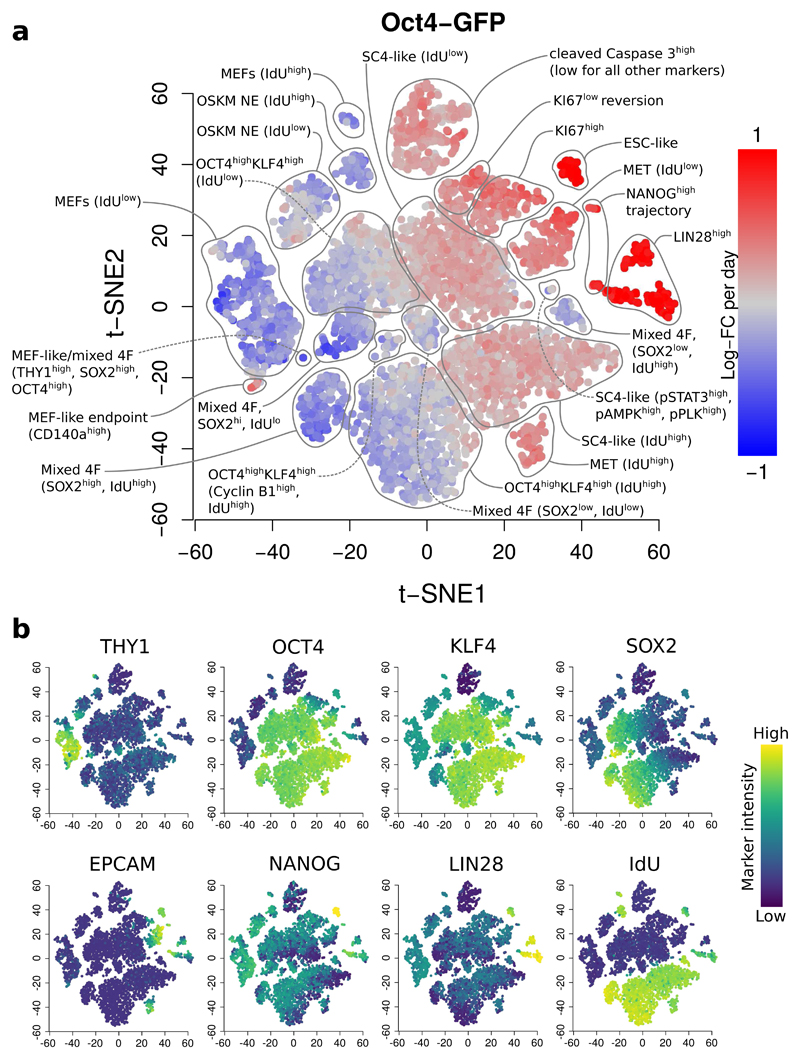

We demonstrate our approach using data from a study of mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) reprogramming17. In this study, three transgenic MEF reporter systems (_Oct4_-GFP, _Nanog_-GFP or _Nanog_-Neo) were reprogrammed to induced pluripotent stem cells. Samples were collected across various points of the reprogramming time course for each MEF reprogramming system. We applied our method to each time course to detect changes in abundance over time, defining putative DA hyperspheres as those detected at a spatial FDR of 5%. In this manner, we detected 7416, 5947 and 21532 DA hyperspheres in the _Oct4_-GFP, _Nanog_-GFP and _Nanog_-Neo time courses, respectively. We applied _t_-SNE18 to the positions of detected hyperspheres to visualize them in a spatial context (Figure 2, Supplementary Figures 13-18). In the _Oct4_-GFP analysis, we recovered previously identified DA subpopulations, including the three reprogramming end points; as well as distinct DA subpopulations that were not clearly characterised in the original analysis, such as a subpopulation of SC4-like cells with phosphorylated STAT3, AMPK and PLK1 that exhibited a non-linear change in abundance over time (Supplementary Figure 19) – see Supplementary Note 6 for details.

Figure 2. Differentially abundant subpopulations in the _Oct4_-GFP time course, detected at a spatial FDR of 5%.

(a) A _t_-SNE plot of the median positions of DA hyperspheres. Each point represents a hypersphere and is coloured according to its average log-fold change in abundance over time. Grey points represent hyperspheres with significant but non-linear changes in abundance. Subpopulations were annotated based on results in Zunder et al.17, with additional distinguishing features for each subpopulation noted in parentheses. OSKM: reprogramming factors (OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, c-MYC), NE: non-expressing, MET: mesenchymal-epithelial transition, SC4: partially reprogrammed cell line, ESC: embryonic stem cells, mixed 4F: mixed stoichiometry of the OSKM factors. (b) The same plots coloured by the median intensity of selected markers in each hypersphere. The colour range for each marker was bounded at the 1st and 99th percentiles of the intensities across all cells.

We also applied our method on another data set examining the effect of interleukin 10 (IL-10) treatment on bone marrow mononuclear cells (BMMCs) across five healthy donors6. Importantly, this data set contained matched stimulated and unstimulated samples from each donor. This experimental design is easily accommodated by the GLM machinery in edgeR, highlighting the flexibility of our framework. We observed changes in abundance associated with phosphorylated STAT3 expression, consistent with the expected biology of IL-10, as well as several interesting DA subpopulations that were not identified by the original study (see Supplementary Note 7, Supplementary Figures 20-21 for details). More generally, shifts in marker intensity for signalling molecules or activation markers will cause changes in abundance that can be detected by the DA analysis (Supplementary Note 8, Supplementary Figure 22).

Finally, we compared our approach to CITRUS12, an existing method that uses an initial clustering step for comparative analysis of mass cytometry data. We simulated a simple scenario involving two adjacent subpopulations with opposite changes in abundance between conditions (Supplementary Note 9, Supplementary Figure 23). These subpopulations were consistently detected as being differentially abundant by our hypersphere-based method but not by CITRUS. We also tested the performance of CITRUS for detecting differentially abundant subpopulations across time in the MEF reprogramming data set. CITRUS did not detect a number of subpopulations that were found by our method (Supplementary Figure 24), nor did it detect any new subpopulations. This suggests that the use of hyperspheres, in combination with edgeR and the spatial FDR, can improve detection of subtle changes in abundance within complex subpopulations that are difficult to cluster.

As mass cytometry becomes more accessible, large-scale experiments containing many conditions and replicates are likely to become increasingly routine. Indeed, a growing number of studies are using mass cytometry in fields such as immunology, haematopoietic development and cancer. We anticipate that our differential abundance analysis pipeline will be useful to researchers planning to perform comparative studies with such data sets.

Online Methods

Data preparation

In this section, we describe the processing of data from the MEF reprogramming study17. For processing of data from the BMMC study6, see Supplementary Note 7 for details.

We obtained de-barcoded flow cytometry standard (FCS) files for each time course from Cytobank (accession number 43324). We applied the logicle transformation19 to the marker intensities in each sample. The transformation parameters were estimated with the estimateLogicle function from the flowCore package20, using pooled cells from all samples in each time course. (This avoids spurious differences from sample-specific transformation.) We gated out cell events with low intensities for the two DNA markers (Iridium-191 and 193), where the threshold was defined as three median absolute deviations below the median intensity for the pooled cells. We saved the transformed and gated intensities into new FCS files for processing with our pipeline. Only the intensities for relevant markers (i.e., no DNA, barcodes) were used for further analysis. Note that normalization of marker intensities between samples is not required for this data set because the samples in each time course were barcoded and pooled for antibody staining and mass cytometry.

Statistical methods for testing differences

To compute _p_-values, hypersphere counts were analyzed using the quasi-likelihood (QL) method in edgeR. First, we filtered out hyperspheres with an average count below 5. This improves efficiency by removing tests without enough information to reject the null hypothesis. For the remaining hyperspheres, we fitted a mean-dependent trend to the NB dispersion estimates. We fitted a NB GLM to the counts for each hypersphere, using the trended dispersion for each hypersphere and the log-transformed total number of cells as the offset for each sample. We estimated the QL dispersion from the GLM deviance and stabilized the estimates by empirical Bayes shrinkage towards a second mean-dependent trend. Finally, we used the QL F-test with a specified contrast to compute a _p_-value for each hypersphere. Details of the statistical framework are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

For the time course analyses, we used a design matrix constructed from a B-spline basis matrix with a time covariate and 3 degrees of freedom. This provided 9, 11 and 10 residual degrees of freedom for dispersion estimation in the _Oct4_-GFP, _Nanog_-GFP and _Nanog_-Neo data sets, respectively. Contrasts were constructed to test whether all spline coefficients were equal to zero. This represents a null hypothesis that time has no effect on abundance. The use of splines accommodates both linear and non-linear trends in abundance with respect to time.

Visualizing the differential hyperspheres

For each hypersphere detected at a spatial FDR of 5%, we defined the median-based position as a set of intensity values across all markers. These values were used to perform _t_-SNE via the Rtsne package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/Rtsne), using a perplexity value of 10. To colour the plot based on differential abundance, a GLM was fitted to the counts for each hypersphere using a design matrix with time as a covariate. This yields a log2-fold change in abundance per day for each hypersphere, corresponding to a blue-to-red gradient for negative-to-positive values respectively. (We assume a linear change in abundance over time for simplicity. This does not affect the significance statistics, which are computed with a spline to account for non-linear trends.) To colour the plot based on marker intensity, the 1st and 99th percentiles of the intensities for all cells were computed for each marker. A linear gradient between these two percentiles was constructed using the viridis colour scheme (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/viridis). Each hypersphere was then assigned a colour based on the location of its median marker intensity on the gradient.

Using CITRUS to analyze the MEF data

To run CITRUS (v0.08), the citrus.full command was used with the featureType argument set to “abundances” and the modelType argument set to “sam”. The family argument was set to “continuous” to identify changes in abundance over time. Downsampling was performed to 1000 cells per sample and the minimum cluster size was set to 5%, based on the default settings. Detected clusters were defined as those reported at a FDR of 5%, as reported by the SAM method. For each detected cluster, the median-based centre was determined and the hypersphere with the closest position to the cluster centre in _M_-dimensional space was identified. Each cluster centre was mapped onto the t_-SNE plot of DA hyperspheres using the coordinates of its closest hypersphere. Note that a cluster centre was not mapped if the distance to the closest hypersphere was greater than 0.5√_M. If an unmapped DA cluster was present, it was treated as being undetected by the hypersphere-based approach.

Implementation of cell counting software

All simulation and analysis code were written in R. Methods in the cydar package were written in a combination of R and C++. Cell counting, nearest-neighbour detection and density estimation were performed using an approach similar to that in X-shift8. Briefly, k_-means clustering was performed on all cells, setting k = √_N where N is the total number of cells. Let |j – t| denote the Euclidean distance between cell j and the centre of cluster t in the _M_-dimensional marker space. Similarly, let |h − t| denote the distance between the centres of t and hypersphere h. Both of these distances only need to be computed once per cell – in the latter case, this is because each hypersphere is centred on a cell. By applying the triangle inequality, a cell j in cluster t was only considered for assignment to a hypersphere h if r + |j − t| ≥ |h − t|. For cells not satisfying this requirement, the distance between j and h was not computed to avoid unnecessary work. Similarly, j was only considered as a possible neighbour of a cell j' if dn + |j − t| ≥ |j' - t| where dn is the distance to the current _n_th nearest neighbour (where the value of dn is continually updated once a closer _n_th nearest neighbour is identified). This speeds up the pipeline while yielding the same results as a naïve approach that computes distances between every pair of cells. On a desktop machine, the analysis takes 10-20 minutes to run for each of the MEF reprogramming time courses.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Materials is a single PDF file that consists of Sections 1-9 and contains Supplementary Figures 1-24 and Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (core funding to J.C.M., award no. A17197), the University of Cambridge and Hutchison Whampoa Limited. J.C.M. was also supported by core funding from EMBL.

Footnotes

Code availability

Simulation and analysis code are accessible at http://github.com/MarioniLab/DAMethods2016. Methods in the DA analysis pipeline are publicly available in the cydar package (mass CYtometry for Differential Abundance analyses in R) from the open-source Bioconductor project at http://bioconductor.org/packages/cydar, or by downloading the Supplementary Software associated with this paper.

Data availability

All data sets used here are publicly available from Cytobank (https://community.cytobank.org), using the accession number 43324 for the MEF study and 44185 for the BMMC study.

Author Contributions

A.T.L.L. developed the analysis pipeline, tested it with simulations and applied it to the real data. A.C.R. interpreted the results to identify the DA subpopulations. J.C.M. provided direction and advice on method development and biological interpretation. All authors wrote and approved the final manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ornatsky OI, et al. Anal Chem. 2008;80:2539–2547. doi: 10.1021/ac702128m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leipold MD, Newell EW, Maecker HT. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1343:81–95. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2963-4_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leelatian N, Diggins KE, Irish JM. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1346:99–113. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2987-0_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansmann L, et al. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:650–660. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0236-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bendall SC, et al. Science. 2011;332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine JH, et al. Cell. 2015;162:184–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qiu P, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:886–891. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Samusik N, Good Z, Spitzer MH, Davis KL, Nolan GP. Nat Methods. 2016;13:493–496. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaudillière B, et al. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:255ra131. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaudillière B, et al. Cytometry A. 2015;87:817–829. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.22720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anchang B, et al. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:1264–1279. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruggner RV, Bodenmiller B, Dill DL, Tibshirani RJ, Nolan GP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:E2770–2777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408792111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronan T, Qi Z, Naegle KM. Sci Signal. 2016;9:re6. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aad1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finak G, et al. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20686. doi: 10.1038/srep20686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCarthy DJ, Chen Y, Smyth GK. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:4288–4297. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Scand J Stat. 1997;24:407–418. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zunder ER, Lujan E, Goltsev Y, Wernig M, Nolan GP. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van der Maaten L, Hinton G. J Mach Learn Res. 2008;9:2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks DR, Roederer M, Moore WA. Cytometry A. 2006;69:541–551. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahne F, et al. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:106. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Materials