Protein structure prediction servers at University College London (original) (raw)

Abstract

A number of state-of-the-art protein structure prediction servers have been developed by researchers working in the Bioinformatics Unit at University College London. The popular PSIPRED server allows users to perform secondary structure prediction, transmembrane topology prediction and protein fold recognition. More recent servers include DISOPRED for the prediction of protein dynamic disorder and DomPred for domain boundary prediction. These servers are available from our software home page at http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/software.html.

INTRODUCTION

The Bioinformatics Unit at University College London offers web servers for a number of cutting edge protein structure prediction methods. The methods allow users to predict a variety of protein structural features, including secondary structure and natively disordered regions, protein domain boundaries and 3D models of tertiary structure.

The web servers employ a number of features to help users become familiar with the software. An online tutorial provides a starting point, guiding them through the interfaces to the different methods. These interfaces have a common look and feel, allowing users to transfer from one server to another. Finally, each server has help pages that provide detailed information on the prediction process.

The following sections describe three of our key servers: PSIPRED for secondary structure prediction, DISOPRED for protein disorder prediction and DomPred for domain boundary prediction. These are available from our software page at http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/software.html, with instructions for citation on each server.

THE PSIPRED SERVER IN 2005

The PSIPRED server was originally developed in 2000 to provide a single unified interface to three structure prediction methods (1). It has gained popularity due to its accuracy, reliability and ease of use; it is now servicing over 15 000 requests each month. Updates in both hardware and software have taken place to maintain its high performance and reliability despite increasing demand.

The users paste the sequence into the submission form and then select one of the three methods: secondary structure prediction, membrane topology prediction or protein fold recognition.

Secondary structure prediction using the PSIPRED method

The PSIPRED secondary structure prediction method (2) is the first option available and gives its name to the server. The original PSIPRED method took the profile output of PSI-BLAST (3) and fed it through two consecutive feed-forward neural networks in order to predict secondary structure. The current version of the method further increases its accuracy by taking a consensus prediction from four independently trained sets of neural networks.

PSIPRED has maintained its position as one of the leading secondary structure prediction methods and currently averages a per residue accuracy (Q3) of ∼78% according to an independent continuous evaluation (4).

Results are emailed to the user and they provide the secondary structure prediction in plain text format with a hypertext link to generate a graphical version of the prediction.

Transmembrane topology prediction using the MEMSAT2 method

The MEMSAT2 method (5) for transmembrane helix topology prediction is the second option available on the PSIPRED server. This is an extension of the original MEMSAT method (6) with increased accuracy owing to the use of PSI-BLAST profiles rather than single sequences. The compatibility of these profiles with particular transmembrane topologies is judged using log-likelihood scores (dynamic programming).

Currently, the method has an estimated accuracy of ∼80% at predicting the topology of all-helical transmembrane proteins and the location of their constituent helical elements within a membrane, according to in-house testing.

The user receives an email providing a summary of the scores obtained when predicting different numbers of transmembrane helices for their sequence, starting at both intra- and extra-cellular locations. Full residue-level details are then given for the most optimal topology.

Protein fold recognition using the GenTHREADER and mGenTHREADER methods

The GenTHREADER method (7) was one of the earliest approaches for rapid fully automated protein fold recognition. One of the advantages of GenTHREADER was that it combined sequence alignment scores with threading potentials (8), via a simple feed-forward neural network classifier. This allowed for the detection of both close sequence relatives and also more distantly related homologs, in addition to providing good sequence to structure alignments.

In 2003, the GenTHREADER method was improved through the incorporation of additional structural information which resulted in the detection of more remote homologs and higher overall quality of the predicted models (9). Recently, the method has also been extended to use profile–profile alignments, further improving its accuracy. As a result, the current mGenTHREADER version has maintained its position as one of the leading independent methods in the recent CAFASP (10) and LiveBench (11) assessments.

GenTHREADER and mGenTHREADER return results in identical formats to the user by email. These contain the top 10 matching folds with their sequence to structure alignments. A hypertext link also provides results in graphical format. Each prediction is assigned a confidence level which relates to an _E_-value within a particular range: CERT (E < 0.001), HIGH (E < 0.01), MEDIUM (E < 0.1), LOW (E < 0.5) and GUESS (E ≥ 0.5). These _E_-values represent the number of expected errors per query.

We have recently been exploring methods for post-processing the output from mGenTHREADER using different model quality assessment algorithms. The resulting server, nFOLD, appears to be better at generating useful structural models for the hardest category of targets, as indicated by in-house testing and its results at the recent CASP6 experiment (http://predictioncenter.llnl.gov/casp6/).

PREDICTING PROTEIN DISORDER USING THE DISOPRED2 SERVER

The DISOPRED2 server (12) can be used to predict regions of native disorder in proteins, whereas PSIPRED can be used to predict secondary structure for static regions of a protein. Native disorder is characterized by regions of a protein that do not have a single static structure but are in a constant flux between different structures. Disorder is often functionally important, being commonly associated with molecular recognition and binding. A PSI-BLAST profile is processed using a support vector machine to predict the probability of each residue being disordered.

DISOPRED is one of the leading methods for predicting disordered regions in proteins. At the CASP6 experiment, the DISOPRED method was shown to be the best method at low false positive rates. The method has a per residue (Q2) accuracy of ∼93% when using the 5% false positive rate threshold (12).

Emailed results give the predicted disorder regions in plain text format and also a hypertext link to a graphical representation of the probability of disorder against sequence residue. This information complements and extends the PSIPRED secondary structure predictions.

PREDICTION OF PROTEIN DOMAINS USING THE DomPred SERVER

It is important to take into account the location of domain boundaries when predicting the overall fold of a protein.

The DomPred server predicts domain boundaries in target sequences using a combined homology and fold recognition-based approach. The sequence homology approach simply attempts to distinguish domain boundaries from overlapping edges in PSI-BLAST multiple sequence alignments. The fold recognition approach relies on secondary structure element alignments, using the DomSSEA method (13), in order to find domain boundaries in more distant homologs.

The DomSSEA method was ranked fourth in the domain prediction category at the recent CASP6 experiment. The method has an accuracy of ∼49% at predicting the domain boundary location within 20 residues using a representative set of two domain chains (13).

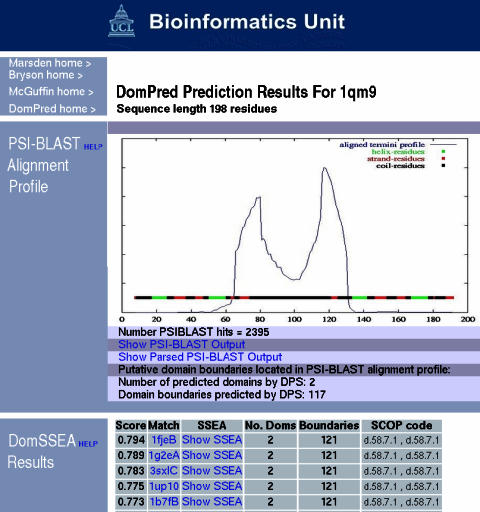

DomPred users are sent an email containing a link to a web page that shows their prediction results (Figure 1). The top of the results page contains the PSI-BLAST alignment plot, where strong peaks indicate putative domain boundaries. Lower down the page is the table of results from the DomSSEA method showing the number of domains, putative boundary locations and hits to folds with domains assigned according to SCOP (14).

Figure 1.

Domain prediction using the DomPred server for the human polypyrimidine tract-binding protein.

EXAMPLE USING DomPred, DISOPRED AND PSIPRED

The human polypyrimidine tract-binding protein (PDB ID 1qm9) provides an interesting example employing two of our new servers to discover a novel feature of this NMR structure.

The DomPred output for this protein is shown in Figure 1. Domains are usually delineated by sharp peaks in the plot. However, this is an unusual case where we have two peaks with a region between them, where the prediction stays relatively high; also only a single domain boundary is predicted. This would be interpreted as a domain boundary consisting of a very long linker region. The DomSSEA results confirm only two domains, both having a ferredoxin-like fold.

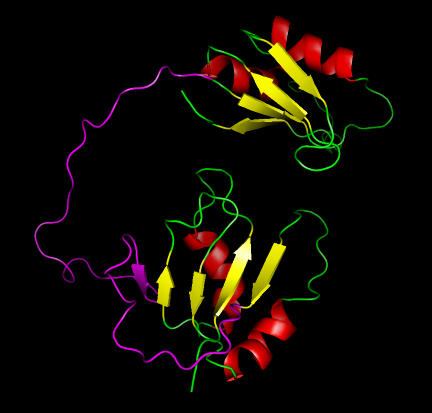

Examining the NMR structure (Figure 2) indicates two domains with a very long linker region as predicted by DomPred. One domain does indeed have a four-stranded ferredoxin-like fold, but the other domain has a five-stranded sheet. Tentatively, DomSSEA seems to have made a mistake. Further investigation, using DISOPRED, reveals a disordered region between these domains, shown in magenta on Figure 2. Examination reveals that this disordered region runs through the fifth strand in the sheet. The chain before this strand also appears to be disordered. It seems likely that this β-strand is either an artifact of the NMR refinement or a transient feature of the native structure. This conclusion is further supported by the PSIPRED prediction, which does not predict this strand but does predict all of the other helices and strands. Thus, we do have two ferredoxin-like folds with a disordered linker region between them, vindicating the DomSSEA prediction.

Figure 2.

Structure of the human polypyrimidine tract-binding protein showing two domains with the disorder regions (magenta) predicted by DISOPRED.

CONCLUSIONS

We have provided an overview of our protein structure prediction servers, together with a practical example of their use. The servers make available accurate protein structure prediction methods, as proven by a number of independent benchmarks.

Acknowledgments

The work described in this article was supported by the Wellcome Trust (K.B.), the BBSRC (L.J.M. and R.L.M.), the DTI (L.J.M.), the MRC (J.J.W. and J.S.S.) and the BioSapiens Network of Excellence funded by the European Commission FP6 Programme, contract number LHSG-CT-2003-503 265 (D.T.J.). Funding to pay the Open Access publication charges for this article was provided by JISC.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McGuffin L.J., Bryson K., Jones D.T. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:404–405. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones D.T. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;292:195–202. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschul S.F., Madden T.L., Schaffer A.A., Zhang J., Zhang Z., Miller W., Lipman D.J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rost B., Eyrich V.A. EVA: large-scale analysis of secondary structure prediction. Proteins. 2001;5:192–199. doi: 10.1002/prot.10051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones D.T. Do transmembrane protein superfolds exist? FEBS Lett. 1998;423:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00095-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. A model recognition approach to the prediction of all-helical membrane protein structure and topology. Biochemistry. 1994;33:3038–3049. doi: 10.1021/bi00176a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones D.T. GenTHREADER: an efficient and reliable protein fold recognition method for genomic sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;287:797–815. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones D.T., Taylor W.R., Thornton J.M. A new approach to protein fold recognition. Nature. 1992;358:86–89. doi: 10.1038/358086a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuffin L.J., Jones D.T. Improvement of the GenTHREADER method for genomic fold recognition. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:874–881. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer D., Rychlewski L., Dunbrack R.L., Jr, Ortiz A.R., Elofsson A. CAFASP3: the third critical assessment of fully automated structure prediction methods. Proteins. 2003;53(Suppl. 6):S503–S516. doi: 10.1002/prot.10538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rychlewski L., Fischer D., Elofsson A. LiveBench-6: large-scale automated evaluation of protein structure prediction servers. Proteins. 2003;53(Suppl. 6):542–547. doi: 10.1002/prot.10535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward J.J., McGuffin L.J., Bryson K., Buxton B.F., Jones D.T. The DISOPRED server for the prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:2138–2139. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsden R., McGuffin L.J., Jones D.T. Rapid protein domain assignment from amino acid sequence using predicted secondary structure. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2814–2824. doi: 10.1110/ps.0209902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murzin A.G., Brenner S.E., Hubbard T., Chothia C. SCOP: a structural classification of proteins database for the investigation of sequences and structures. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;247:536–540. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]