Intracellular Signaling Molecules Activated by Epstein-Barr Virus for Induction of Interferon Regulatory Factor 7 (original) (raw)

Abstract

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1) is the principal oncogenic protein in the EBV transformation process. LMP-1 induces the expression of interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7) and activates IRF-7 protein by phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. LMP-1 is an integral membrane protein with two regions in its C terminus that initiate signaling processes, the C-terminal activator regions 1 (CTAR-1) and CTAR-2. Here, genetic analysis of LMP-1 has determined that the PXQXT motif that governs the interaction between LMP-1 CTAR-1 and tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) is needed to induce the expression of IRF-7. Mutations in the PXQXT motif in CTAR-1 that disrupt the interaction between LMP-1 and TRAFs abolished the induction of IRF-7. Also, dominant-negative mutants of TRAFs inhibited the induction of IRF-7 by CTAR-1. The last three amino acids (YYD) of CTAR-2 are also important for the induction of IRF-7. When both PXQXT and YYD were mutated (LMP-DM), the LMP-1 mutant failed to induce IRF-7. Also, LMP-DM blocked the induction of IRF-7 by wild-type LMP-1. These data strongly suggest that both CTAR-1 and CTAR-2 of LMP-1 independently induce the expression of IRF-7. In addition, NF-κB is involved in the induction of IRF-7. A superrepressor of IκB (sr-IκB) could block the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1, and overexpression of NF-κB (p65 plus p50) could induce the expression of IRF-7. In addition, we have found that human IRF-7 is a stable protein, and sodium butyrate, a modifier of chromatin structure, induces IRF-7.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is a human herpesvirus of increasing medical importance. EBV infection is associated with the development of nasopharyngeal carcinoma and Burkitt's lymphoma (BL). In addition, EBV infection is an important cause of lymphomas in severely immunocompromised persons, especially patients with AIDS and organ transplant recipients (24, 36–38, 40). In vitro, EBV efficiently infects and immortalizes primary B-lymphocytes, and latent membrane protein 1 (LMP-1) expression is required for this immortalization process (22, 26). LMP-1 can induce a variety of cellular genes that enhance cell survival (13, 17, 32, 44) and adhesive (45), invasive, and angiogenic potential (35, 48).

LMP-1 is an integral membrane protein with six transmembrane-spanning domains and a long C-terminal domain, which is located in the cytoplasm (24, 28). LMP-1 acts as a constitutively active receptor-like molecule that does not need the binding of a ligand (16). The six transmembrane domains mediate oligomerization of LMP-1 molecules in the plasma membrane, a prerequisite for LMP-1 function (12, 16). Roughly, two regions in the C terminus of LMP-1 have been shown to initiate signaling processes, the C-terminal activator regions 1 (CTAR-1) (amino acids 194 to 231) and CTAR-2 (amino acids 332 to 386) (Fig. 1) (18, 34).

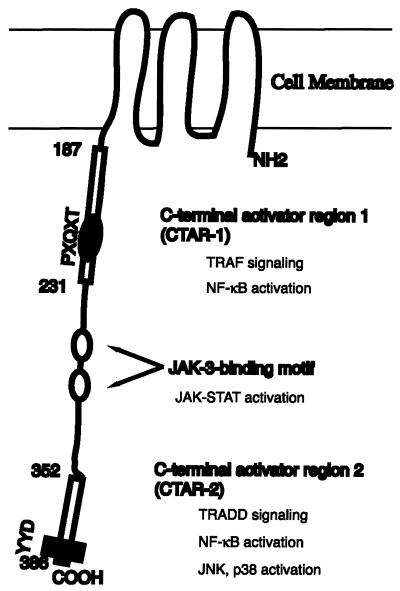

FIG. 1.

Molecular structure and locations of functional domains in LMP-1. LMP-1 contains a short cytoplasmic amino terminus, a transmembrane hydrophobic domain, and a long cytoplasmic carboxy terminus that contains three major signaling domains. CTAR-1 mediates interaction with the TRAFs and is the minor NF-κB-activating region. The location of the TRAF-interacting motif, PXQXT, is indicated. CTAR-2 is the major NF-κB-activating region. Also, CTAR-2 can activate JNK and p38 molecules. Two JAK-3-binding sites are indicated. The JAK-STAT pathway can be activated by the interaction between JAK-3 and LMP-1. The amino acid numbers are shown. The drawing is not to scale.

CTAR-1 is a minor contributor to the activation of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) by LMP-1 (about 25%). The PXQXT motif localized within CTAR-1 is involved in the interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs). TRAF1, -2, -3, and -5 associate with LMP-1 with different affinities and are responsible for NF-κB activation by CTAR-1 (6, 7, 33, 41). CTAR-1 is responsible for induction of epidermal growth factor receptor and TRAF1 (7, 33). CTAR-1 is required for the transformation of B cells by EBV, and the PXQXT motif is essential for this process (20, 23).

CTAR-2 is a major contributor to the activation of NF-κB by LMP-1 (about 75%). CTAR-2, through its interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain protein (TRADD), activates NF-κB (19, 21). Also, c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 are activated by CTAR-2 (9, 10, 25). The last three amino acids (YYD) of CTAR-2 have been shown to play an essential role in the activation of NF-κB.

Recently, two Janus kinase 3 (JAK-3) binding sites have been identified, which are located between CTAR-1 and CTAR-2 (Fig. 1). JAK-3 can bind to these sites and is responsible for the activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT-1) (15).

Interferon regulatory factor 7 (IRF-7) was first cloned by its binding activity to the EBV _Bam_HI Q promoter (Qp) used in latently infected EBV infection for transcription of EBNA-1, and it has subsequently been implicated as a negative regulator of the type I latency promoter, Qp (50, 51, 53). IRF-7 is also involved in the activation of cellular Tap-2 and interferon (IFN) genes (1, 30, 47, 52).

LMP-1 has a strong relation with IRF-7. LMP-1 regulates IRF-7 in three ways: (i) induction of the expression of IRF-7, (ii) initiation of the phosphorylation of IRF-7, and (iii) facilitation of the nuclear translocation of IRF-7 (51, 52). However, how LMP-1 induces IRF-7 is completely unknown. In this report, the experiments were designed to determine the contributions of various signaling molecules involved in the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1. The genetic analysis of LMP-1 has identified both CTAR-1 and CTAR-2 as independently inducing the expression of IRF-7. In addition, TRAFs and NF-κB are involved in the induction of IRF-7.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells, plasmids, and antibodies.

DG75 is an EBV-negative BL cell line (2). Jijoye is an EBV-positive BL line with type III latency (39). Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 plus 10% fetal bovine serum. pcDNA/CD4 is a human CD4 expression plasmid (gift of Jenny Ting). The LMP-1 expression plasmid, pcLMP1, was a gift from Tomakazu Yoshizaki. The mutant LMP-1 plasmid, LMP1–187, was a gift from Nancy Raab-Traub (33). Other LMP-1 serial mutants were made by PCR and cloning of the corresponding fragments into the pcDNA3 vector; all the clones were sequenced. mLMP1–231 was made with the corresponding mutations in a PCR fragment. pQ3-CAT (−33 to +5) was made by cloning the corresponding PCR fragment into pBS-CAT (14). The pQ3M-CAT plasmid was made in a way similar to the method for pQ2M-CAT by mutation in the interferon-stimulated response element (ISRE) region (51). The TRAF1 dominant-negative expression plasmid was a gift from Collin Duckette (8), and TRAF2 and TRAF3 dominant-negative plasmids were gifts from Nancy Raab-Traub. The JAK-3 dominant-negative mutant was a gift from John O'Shea (4). The TRAF5 dominant-negative mutant was made by cloning the C-terminal amino acids 233 to 557 of TRAF5 into the pcDNA3 vector. The expression of the TRAF5 fragment was confirmed by Western blot analysis and was confirmed functionally by inhibition of NF-κB activity (data not shown). NF-κB expression plasmids (p65 and p50) and the superrepressor IκB (sr-IκB) plasmid were gifts from Albert Baldwin. TRAF5 antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc (sc-6195). LMP-1 monoclonal antibody, CS1–4, was purchased from Dako. Anti-Flag monoclonal antibody, M2, was purchased from IBI. Tubulin antibody was purchased from Sigma. Human IRF-3 monoclonal antibody was a gift from Peter Howley (47).

Western blot analysis with enhanced chemiluminescence.

Separation of proteins by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis followed standard procedures. After the proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose or Immobilon membrane, the membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBST (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 200 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20) at room temperature for 10 min. It was then washed briefly with water and incubated with a primary antibody in 5% milk in TBST for 1 to 2 h at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After a wash with TBST for 10 min three times, the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. It was then washed three times with TBST as before, treated with ECL (Amersham) or SuperSignal (Pierce) detection reagents, and exposed to Kodak XAR-5 film.

Transient transfection, CAT assays, and isolation of transfected cells.

For DG75, 107 cells in 0.5 ml of medium were used for transfection with the use of a Bio-Rad Gene Pulser (320 V and 925 μF). Two days after transfection, cells were collected for a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assay or for isolation of transfected cells. The CAT and β-galactosidase assays were carried out essentially as described previously (50, 53). The CAT assay results were analyzed on a Molecular Dynamics PhosphorImager.

For isolation of transfected cells, cells were collected after transfection, and enrichment for CD4-positive cells was performed with the use of CD4 antibody conjugated to magnetic beads according to the manufacturer's recommendation (Dynal, Inc.). The isolated cells were used for the extraction of total RNA with the RNease Total RNA Isolation Kit (Qiagen).

RNA extraction and RPA.

RNase protection assays (RPA) were performed with total RNA with the RNase Protection Kit II (Ambion, Inc.). The hybridization temperature was 53°C or gradient temperatures (49). The human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) probe was supplied by U.S. Biochemicals, Inc. The IRF-7 probe was generated with the use of _Apa_LI-digested pBS-IRF7A as a template and T7 RNA polymerase. The protected region consists of nucleotides 1671 to 1890 of IRF-7A (53). This probe cannot distinguish various splicing forms of IRF-7.

Detection of stabilities of proteins.

DG75 and Jijoye cells were treated with cycloheximide (Sigma) at a concentration of 75 μg/ml; cell lysates were made at various time points. The protein concentration of the lysates was determined, and Western blot analysis was used to determine the half-lives of proteins with various specific antibodies.

RESULTS

LMP-1-activated TRAF molecules are involved in the induction of IRF-7.

To test which domain is responsible for the induction of IRF-7, LMP-1 mutants along with a CD4 expression plasmid were transiently transfected into DG75 cells, an EBV-negative cell line, and transfected cells were selected by the use of CD4 antibody conjugated to magnetic beads (see Materials and Methods for details). RPA was performed with total RNAs isolated from transfected cells. As shown in Fig. 2, results with deletion mutants suggest that CTAR-1 is able to induce IRF-7 (Fig. 2B, lanes 4 to 7). The efficiency of CTAR-1 for the induction is about 60 to 70% of that of wild-type LMP-1 (compare lanes 5 and 7). Furthermore, the fact that CTAR-1 contributes to induction of IRF-7 RNA suggests that the PXQXT domain might be important because the domain is the only one that is currently known in CTAR-1 (7, 31, 41). A series of LMP-1 mutants within CTAR-1 were generated, as shown in Fig. 2A. The deletion mutant LMP1–212, which preserves the TRAF interaction domain, was able to induce the expression of IRF-7; however, LMP1–200 lacks the PXQXT domain and was unable to induce IRF-7 (Fig. 2B, lanes 9 to 12).

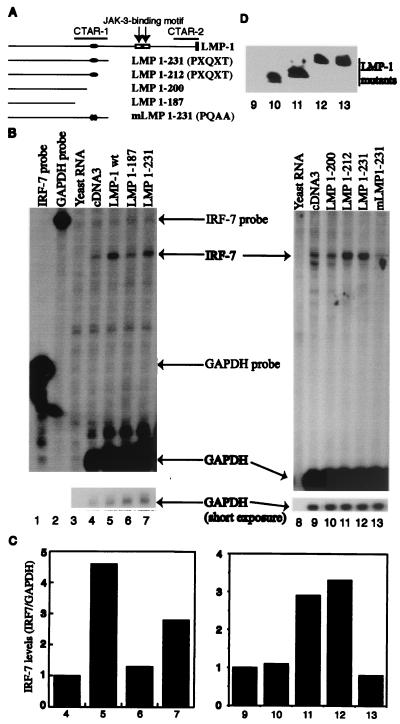

FIG. 2.

The LMP-1 TRAF interaction domain is important for IRF-7 induction. (A) Schematic diagram of LMP-1 mutants. CTAR-1, CTAR-2, and JAK-3-binding motifs and amino acid numbers are shown. Solid oval, PXQXT motif. (B) The TRAF interaction domain in CTAR-1 is responsible for the induction of IRF-7. RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes. Lane 1, yeast RNA; lanes 2 to 7, RNAs from transfected DG75 cells. Lane 2, pcDNA3 transfected; lane 3, LMP1–200; lane 4, LMP1–212; lane 5, LMP1–231; lane 6, mLMP1–231. Specific RNA protections are shown. Bottom panel, short-time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas. A representative result from three independent experiments is shown. (C) Relative IRF-7 levels from panel B. Data were obtained by normalizing IRF-7 RNA levels to GAPDH RNA levels with the use of a PhosphorImager. The column numbers match the lanes in panel B. (D) Western blot analysis of transfected cells. The Flag antibody, M2, was used for detection of these LMP-1 mutants. The identity of proteins is indicated. The lane numbers match the lanes in panel B.

To probe the role of the TRAF interaction domain further, mLMP1–231, which has point mutations that change the PXQXT motif into AXAXT, was generated. Genetically, the association with TRAFs can be destroyed by mutating the amino acid sequence to AXAXA (PQAA mutation) (7, 31). As shown in Fig. 2B, mLMP1–231 failed to induce IRF-7 (lane 13). Also, the expression levels of these LMP-1 mutant proteins were approximately the same (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the TRAF interaction domain is important for the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1.

Dominant-negative mutants of TRAFs block the induction of IRF-7.

To examine the involvement of endogenous TRAF molecules in the activation of IRF-7, dominant-negative mutants of TRAF (TRAF DNs) were transfected into DG75 cells along with LMP1–212, and the induction of IRF-7 was examined. As shown in Fig. 3, the TRAF dominant-negative mutants tested could partially block the induction of endogenous IRF-7 (lanes 3 to 6). Because the TRAF mutants did not obviously affect the expression of LMP-1 (Fig. 3C), these data suggest that the endogenous TRAFs are involved in the induction of IRF-7.

FIG. 3.

Dominant-negative mutants of TRAF molecules inhibit the induction of IRF-7. (A) RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes with RNAs from transfected DG75 cells. Lane 1, pcDNA3 transfected; lane 2, LMP1–212; lane 3 to 6, LMP1–212 plus TRAF1DN, TRAF2DN, TRAF3DN, and TRAF5DN, respectively. Specific protections and undigested probes are shown. Bottom panel, short-time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas. A representative result from three independent experiments is shown. (B) Relative IRF-7 levels from Fig. 3A. Data were obtained by normalizing IRF-7 RNA levels to GAPDH RNA levels with the use of a PhosphorImager. The column numbers match the lanes in panel A. (C) Western blot analysis of transfected cells with various antibodies. The identities of the proteins are indicated. The Flag antibody, M2, was used for detection of LMP1–212. The lane numbers match the lanes in panel A.

Two CTARs independently induce the expression of IRF-7.

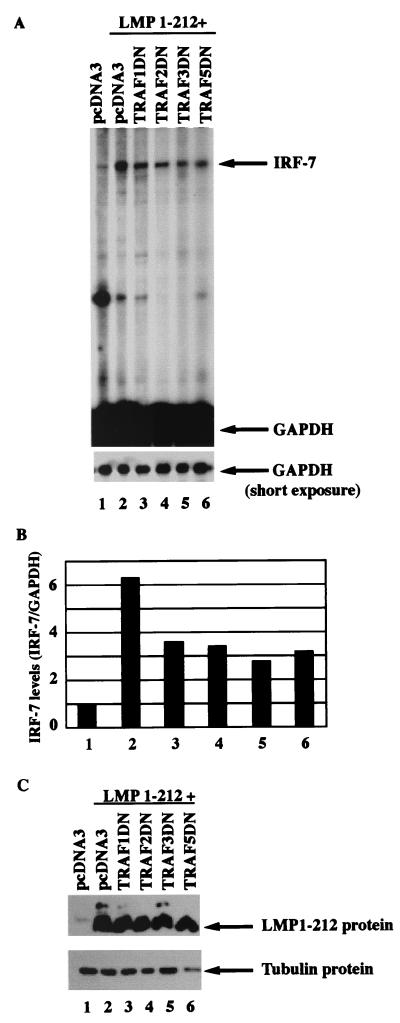

Although CTAR-1 and the TRAF interaction domain in particular are involved in the induction of IRF-7, we tested the role of TRAFs in the context of the whole LMP-1 molecule in the induction of IRF-7. As shown in Fig. 4B (lanes 3 to 5), PQAA mutation in intact LMP-1 does not affect the ability of LMP-1 to induce IRF-7. Also, TRAF dominant-negative mutants cannot block the induction of IRF-7 by the intact LMP-1 molecule (data not shown). These results suggest that the other region of LMP-1 also is able to induce the expression of IRF-7. To address the point further, the whole CTAR1 region was deleted, and the mutant LMP1ΔCTAR1 was transfected into the cells and tested for induction. As expected, LMP1ΔCATR1 was able to induce the expression of IRF-7 (Fig. 4B, lane 11). These data strongly indicate that an independent signaling pathway(s), other than that derived from CTAR1, is also able to induce the expression of IRF-7.

FIG. 4.

Two CTARs independently induce the expression of IRF-7. (A) Schematic diagram of LMP-1 mutants. CTAR-1, CTAR-2, and JAK-3-binding motifs are indicated. (B) Two CTARs independently induce the expression of IRF-7. RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes. Lanes 1, 8, and 12, yeast RNA. Lanes 6 and 7, undigested GAPDH and IRF-7 probes. In all other lanes, RNAs from transfected DG75 cells were used. Lanes 2, 9, and 13, pcDNA-3; lane 3, wild-type (wt) LMP-1; lanes 4, 5, 10, and 14, LMP-PQAA; lane 11, LMPΔCTAR1; lane 15, LMP-IID; and lane 16, LMP-DM. Specific RNA protections are shown. Bottom panel, short-time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas. A representative from three independent experiments is shown. (C) Relative IRF-7 levels from panel B. Data were obtained by normalizing IRF-7 RNA levels to GAPDH RNA levels with the use of a PhosphorImager. The column numbers match the lanes in panel B. (D) Western blot analysis of transfected cells with LMP-1 antibody. The lane numbers match the lanes in panel B.

To address the possible contribution from the other region of the LMP-1 molecule, mutations in CTAR2 were made as shown in Fig. 4A. The tyrosines (Y) in the last three amino acids of LMP-1 (YYD) have been shown to play an important role in the signaling pathway of CTAR2; the mutations of YYD abolish TRADD binding and the activation of NF-κB and AP-1 (11, 21, 25). When these amino acids were mutated from YYD to IID in the whole LMP-1 molecule, there was no effect on induction of IRF-7 (Fig. 4B, lane 15), presumably due to the intact CTAR-1. However, when both CTARs were mutated, the induction of IRF-7 was completely blocked (lane 16). These data indicate that CTAR1 and CTAR2 independently induce the expression of IRF-7.

Mutation in both CTARs of LMP-1 has a dominant-negative effect on induction of IRF-7.

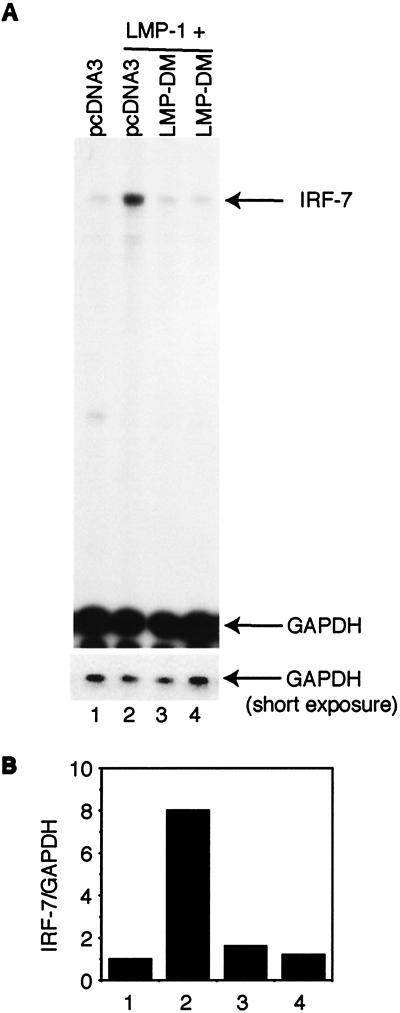

Recently there was a report that mutation in both CTARs resulted in a dominant-negative mutant of LMP-1 (3). Since our LMP-1 mutant in both CTARs (LMP-DM) is similar to the one described in that report, and because LMP-DM fails to induce IRF-7, we tested whether LMP-DM could block the induction of IRF-7. As shown in Fig. 5, LMP-1 itself causes the induction of IRF-7 (lane 2). However, LMP-DM could block the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1 (lanes 3 and 4), which strongly suggests that CTAR1 and CTAR2 independently induce the expression of IRF-7 and that LMP-DM may act as a dominant-negative mutant for LMP-1, at least in the induction of IRF-7.

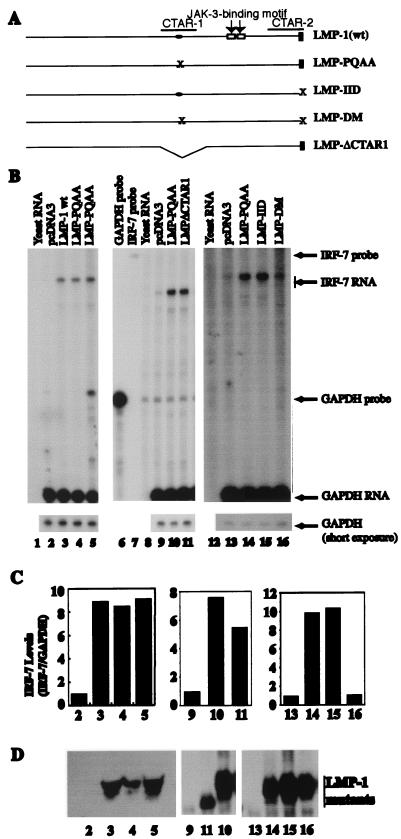

FIG. 5.

LMP-DM blocks the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1. (A) RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes with RNAs from transfected DG75 cells. Lane 1, pcDNA3 transfected; lane 2, LMP-1 plus pcDNA3; lanes 3 and 4, LMP-1 plus LMP-DM. The ratio between LMP-1 and LMP-DM plasmids was 1 to 4. Specific RNA protections are shown. Bottom panel, short time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas. A representative result from three independent experiments is shown. (B) Relative IRF-7 levels from Fig. 5A. Data were obtained by normalizing IRF-7 RNA levels to GAPDH RNA levels with the use of a PhosphorImager. The column numbers match the lanes in panel A.

NF-κB is essential for the induction of IRF-7.

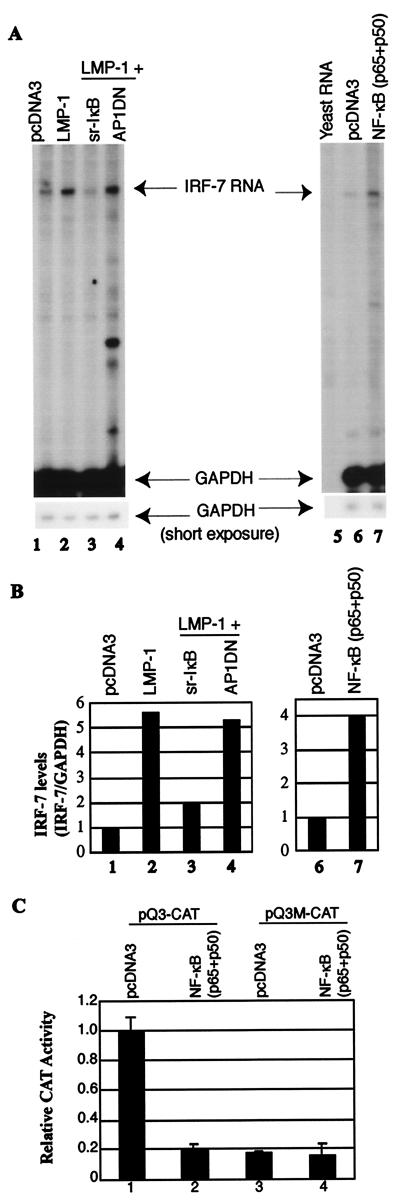

The fact that CTAR1 and CTAR2 independently induce IRF-7 suggests the existence of a common signaling pathway(s) or molecule(s) used for induction. LMP-1 CTARs can activate several frequently used signaling molecules with the activation of NF-κB in common. The role of NF-κB in the induction of IRF-7 was examined with the use of a superrepressor IκB (sr-IκB) plasmid. When transfected into the cells along with LMP-1, sr-IκB could significantly repress the endogenous and LMP-1-activated NF-κB activity (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 6, sr-IκB could also block the activation of IRF-7 by LMP-1 (lane 3). In contrast, a dominant-negative mutant for activator protein 1 (AP1DN) could not (lane 4). AP1DN could block the activation of an AP-1 reporter construct in transient transfection assays, indicating that AP1DN was functional (data not shown). In addition, sr-IκB did not obviously affect the expression levels of LMP-1 (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

NF-κB is involved in the induction of IRF-7. (A) RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes. RNAs from transfected DG75 cells were used. Lanes 1 and 5, pcDNA3 transfected; lane 2, LMP-1; lane 3, LMP-1 plus sr-IκB; lane 4, LMP-1 plus AP1DN. Lane 5, yeast RNA; lane 6, pcDNA3; and lane 7, p65 plus p50 expression plasmids. Specific RNA protections are shown. Bottom panel, short time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas. A representative result is shown. (B) Relative IRF-7 levels from Fig. 4A. Data were obtained by normalizing IRF-7 RNA levels to GAPDH RNA levels with the use of a PhosphorImager. The column numbers match the lanes in panel A. (C) Repression of Qp reporter by NF-κB. DG75 cells were transfected with the Qp reporter constructs, pQ3-CAT (columns 1 and 2), or pQ3M-CAT (columns 3 and 4), together with pcDNA-3 vector (columns 1 and 3), or with NF-κB expression plasmids (p65 plus p50) (columns 2 and 4). CAT assay results were normalized by β-galactosidase activity; Qp CAT activity is expressed relative to the vector control. Standard deviations are shown.

To test the role of NF-κB directly, p65 and p50 expression plasmids were transfected into DG75 cells to generate active NF-κB molecules, and endogenous IRF-7 was measured by RPA. As shown in Fig. 6, overexpression of NF-κB could induce IRF-7 in DG75 cells. To test whether the induced IRF-7 was functional, CAT assays were performed with a Qp reporter construct. IRF-7 represses Qp activity, and as expected, NF-κB could repress Qp (Fig. 6C, column 2). Whether the repression depended on an intact ISRE element in the Qp construct was examined. The pQ3M-CAT construct, which has low but distinct activity, has mutations in the Qp ISRE sequence that disrupt the IRF-7–Qp interaction (see Materials and Methods for details (50, 51). If NF-κB inhibits the reporter activity through IRF-7, then NF-κB should not inhibit the mutated construct. The results showed that NF-κB inhibited Qp through the induction of IRF-7 because the repression depended on the intact ISRE element in the Qp construct (column 4). These data indicated that the induced IRF-7 protein is functional and that NF-κB is needed for induction of IRF-7.

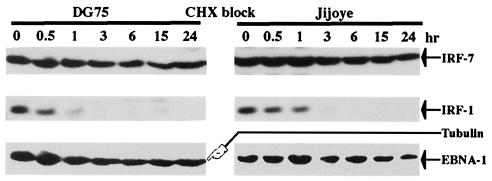

Human IRF-7 protein is a stable protein.

It has recently been reported that IRF-7 is an unstable protein with a half-life of less than 1 h (42). Because IRF-7 protein levels did not change obviously during the cell cycle (Zhang, Davenport, and Pagano, unpublished results), suggesting that IRF-7 is a relative stable protein, we were interested in examining its half-life. DG75 and Jijoye cells were treated with cycloheximide, and cell lysates were made at various time points. Western blot analysis was used to determine the half-lives of proteins with various specific antibodies. As shown in Fig. 7, tubulin and EBNA-1 had very long half-lives, while IRF-1 had a very short half-life, as expected (5, 43, 46). Because the half-lives of both EBNA-1 and tubulin are more than 24 h (5, 43), and because the expression pattern of IRF-7 protein after cycloheximide block is similar to that of EBNA-1 and tubulin (Fig. 7), the half-life of IRF-7 protein is probably more than 24 h. Finally, it should be noted that the IRF-7 protein in Jijoye cells is mainly active (i.e., phosphorylated and localized in the nucleus), whereas in DG75 cells, IRF-7 protein is mainly inactive (52). Apparently, the phosphorylation status of IRF-7 does not obviously affect its protein stability. Interestingly, the half-life of IRF-3 in these two cell lines was very long, similar to IRF-7, as reported previously (42; also data not shown).

FIG. 7.

Human IRF-7 is a stable protein. DG75 and Jijoye cells were treated with cycloheximide (75 μg/ml), and cell lysates were made at given times (hr) after treatment. Western blot analysis with various antibodies was carried out with different parts of the membrane or with the same membrane with a different antibody after striping of the previous one. More cell lysate from DG75 was used to obtain a level of IRF-7 similar to that obtained from Jijoye cells. The identities of the proteins are indicated.

These observations seem to contradict the recent report that IRF-7 has a very short half-life (0.5 to 1 h) (42). The conflicting results may be due to the following. (i) Human IRF-7 (hIRF-7) and mouse IRF-7 (mIRF-7) are different. (ii) The half-life of mIRF-7 was determined by the use of a hemagglutinin-tagged IRF-7 construct. The hemagglutinin sequence may affect mIRF-7 stability. (iii) The cells used to determine the half-life of mIRF-7 were fibroblasts (42). However, IRF-7 is predominantly a lymphoid-specific factor (1, 53), and overexpression of IRF-7 in a nonnative environment might affect its stability. Here, the half-life of hIRF-7 was determined by examining the native form in its native environment under physiological concentrations. It is possible that degradation of IRF-7s may differ in different cell types.

DISCUSSION

It is a common phenomenon for a virus to usurp cellular genes for its own functions. LMP-1 regulates IRF-7 in several ways, including stimulation of its expression and facilitation of its phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. By doing so, LMP-1 uses IRF-7 as a secondary mediator to regulate some target genes, both cellular and viral, such as those for Tap-2 and Qp-derived EBNA-1 (51–53). Here we have studied the first steps of this apparently important signal transduction pathway leading to the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1.

First, our results provide strong evidence that the two regions (CTARs) of LMP-1 can independently induce the expression of IRF-7. LMP-1 mutants with a single mutation in either CTAR that abolishes the function could still induce IRF-7. Only mutations in both CTARs of LMP-1 (LMP-DM) led to failure to induce the expression of IRF-7 in transfected cells (Fig. 4). In addition, LMP-DM, which functions as a dominant-negative mutant, blocks the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1 (Fig. 5). Considering that LMP-1 is an integral membrane protein and depends heavily, if not exclusively, on cellular signaling molecules for its function, the implication from these results is that IRF-7 might be an important factor for LMP-1 function and that two independent regions of LMP-1 might be needed, regardless of different cellular environments, to ensure the induction of IRF-7.

Second, activation of endogenous TRAFs is involved in the induction of IRF-7: (i) CTAR-1 deletion mutants of LMP-1, provided they contain the PXQXT motif, are capable of inducing the expression of IRF-7 (Fig. 2 and 3); (ii) mutations in the PXQXT motif in CTAR-1, which abolish the interaction with TRAFs, fail to induce IRF-7 (Fig. 3); and (iii) dominant-negative mutants of TRAFs are capable of blocking the induction of IRF-7 by CTAR-1 (Fig. 4). These data strongly suggest that TRAFs are involved in the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1.

Third, NF-κB is an essential factor for the induction of IRF-7. Coexpression of sr-IκB blocked the induction of IRF-7. Overexpression of NF-κB could induce IRF-7 in the same cells (Fig. 5). Also, the promoter sequence of human IRF-7 is available in the gene bank, and four consensus NF-κB-binding sites have been identified in a 3-kb fragment directly in front of the IRF-7 translational initiation codon (data not shown). These data clearly indicate that active NF-κB is necessary for the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1. However, activation of endogenous NF-κB alone apparently is not sufficient to induce IRF-7. In the Akata Burkitt's lymphoma cell line, LMP-1 activated NF-κB, but it could not induce IRF-7 under the same experimental conditions (51; also data not shown). In DG75 cells, LMP1–231 could induce the expression of IRF-7 (Fig. 2); however, LMP1–231 did not detectably activate NF-κB, presumably due to the high level of endogenous NF-κB activity in these cells (data not shown). NF-κB activation reagents, such as gamma IFN (IFN-γ) and tumor necrosis factor alpha, could not induce IRF-7 in DG75 cells (1, 51; also data not shown). All these data suggest that NF-κB is a necessary but not sufficient factor for the induction of IRF-7.

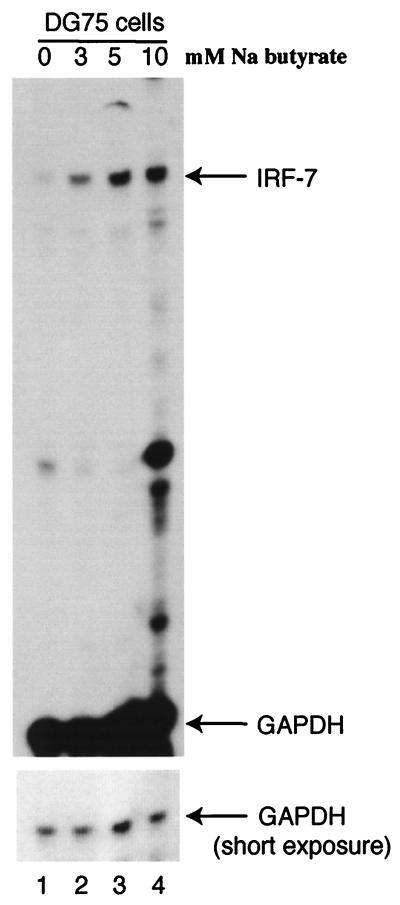

Interestingly, LMP-1 marginally activated the IRF-7 promoter reporter constructs that contain several NF-κB-binding sites (two- to threefold; data not shown). However, in the same cells and with the same conditions, LMP-1 strongly induced the endogenous IRF-7 RNA levels (6- to 10-fold; Fig. 4 to 6). Because LMP-1 did not obviously affect the stability of IRF-7 RNA (data not shown), one possibility is that the promoter reporter construct lacks some critical _cis_-acting element(s). Another possibility is the chromosomal structure. Because the major difference between transiently transfected DNA and endogenous genomic DNA is its structure, LMP-1 may affect the chromosomal structure that in turn plays an important role in the activation of IRF-7. To test such a notion, we examined whether sodium butyrate, a known chromosomal modifier acting through cellular histones (27), could affect the expression of IRF-7. As shown in Fig. 8, sodium butyrate induces the expression of IRF-7 in DG75 cells, suggesting that chromosomal structure might be involved in the regulation of endogenous IRF-7. Sodium butyrate also induced the expression of IRF-7 in EBV-positive Burkitt's lymphoma cell lines (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Sodium butyrate induces the expression of IRF-7. (A) RPA was performed with IRF-7 and GAPDH probes with RNAs from DG75 cells. Lane 1, untreated cells; lanes 2 to 4, treatments with 3, 5, and 10 mM sodium butyrate for 24 h, respectively. Specific RNA protections are shown. Bottom panel, short-time exposure for GAPDH-protected areas.

The induction of IRF-7 by IFN-α treatment (1, 30, 51) suggests that the JAK-STAT signaling pathway is important for the induction of IRF-7. Recently, LMP-1 has been reported to interact with JAK-3 molecules and activate STAT-1 (15). However, a JAK-3 dominant-negative mutant that blocks the activation of JAKs (4) could not block the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1 (data not shown). Also, LMP1–231, which lacks the JAK-3 interaction site, is capable of inducing IRF-7 (Fig. 2). LMP-DM that retains the intact JAK-3 interaction site is unable to induce IRF-7 (Fig. 4). It seems that JAK-3 may not play a critical role, but at best may play a cooperative role in the induction of IRF-7 by LMP-1. In sharp contrast, the JAK-STAT pathway plays a pivotal role in the induction of IRF-7 by IFN-α (29, 30, 42). It is clear that the different inducers use different signaling molecules for the induction of IRF-7.

In summary, our data provide evidence that two regions of LMP-1 independently induce IRF-7, which is a secondary mediator for the LMP-1 protein in modulating its cellular and viral functions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nancy Raab-Traub, Albert Baldwin, Collin Duckett, Charles Vinson, John O'Shea, Min Chen, Jenny Ting, and Peter Howley for providing valuable reagents for this work. We thank Shannon Kenney for critical reading of the manuscript and are grateful for technical help from Ho-Sun Park and the UNC sequencing facility.

The research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI 42372–01) and the National Cancer Institute (CA 19014).

REFERENCES

- 1.Au W C, Moore P A, LaFleur D W, Tombal B, Pitha P M. Characterization of the interferon regulatory factor-7 and its potential role in the transcription activation of interferon A genes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:29210–29217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.44.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Bassat H, Goldblum N, Mitrani S, Goldblum T, Yoffey J M, Cohen M M, Bentwith Z, Ramot B, Klein E, Klein G. Establishment in continuous culture of a new type of lymphocyte from a “Burkitt-like” malignant lymphoma (line D.G.-75) Int J Cancer. 1977;19:27–33. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan P, Floettmann J E, Mehl A, Jones M, Rowe M. Mechanism of action of a novel latent membrane protein-1 dominant negative. J Biol Chem. 2001;2001:1195–1203. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen M, Cheng A, Chen Y Q, Hymel A, Hanson E P, Kimmel L, Minami Y, Taniguchi T, Changelian P S, O'Shea J J. The amino terminus of JAK3 is necessary and sufficient for binding to the common gamma chain and confers the ability to transmit interleukin 2-mediated signals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6910–6915. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davenport M, Pagano J S. Expression of EBNA-1 mRNA is regulated by cell cycle during Epstein-Barr virus type I latency. J Virol. 1999;73:3154–3161. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.3154-3161.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devergne O, Hatzivassiliou E, Izumi K, Kaye K, Kleijnen M, Kieff E, Mosialos G. Association of TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3 with an Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 domain important for B lymphocyte transformation: role in NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7098–7108. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devergne O, McFarland E C, Mosialos G, Izumi K M, Ware C F, Kieff E. Role of the TRAF binding site and NF-κB activation in Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1-induced cell gene expression. J Virol. 1998;72:7900–7908. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.10.7900-7908.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duckett C S, Gedrich R W, Gilfillan M C, Thompson C B. Induction of nuclear factor κB by the CD30 receptor is mediated by TRAF1 and TRAF2. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1535–1542. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eliopoulos A G, Blake S M, Floettmann J E, Rowe M, Young L S. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 activates the JNK pathway through its extreme C terminus via a mechanism involving TRADD and TRAF2. J Virol. 1999;73:1023–1035. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1023-1035.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eliopoulos A G, Young L S. Activation of the cJun N-terminal kinase (JNK) pathway by the Epstein-Barr virus-encoded latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) Oncogene. 1998;16:1731–1742. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Floettmann J E, Rowe M. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) C-terminus activation region 2 (CTAR2) maps to the far C-terminus and requires oligomerization for NF-κB activation. Oncogene. 1997;15:1851–1858. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Floettmann J E, Ward K, Rickinson A B, Rowe M. Cytostatic effect of Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 analyzed using tetracycline-regulated expression in B cell lines. Virology. 1996;223:29–40. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fries K L, Miller W E, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 blocks p53-mediated apoptosis through the induction of the A20 gene. J Virol. 1996;70:8653–8659. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8653-8659.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furnari F B, Adams M D, Pagano J S. Regulation of the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase gene. J Virol. 1992;66:2837–2845. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.5.2837-2845.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gires O, Kohlhuber F, Kilger E, Baumann M, Kieser A, Kaiser C, Zeidler R, Scheffer B, Ueffing M, Hammerschmidt W. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus interacts with JAK3 and activates STAT proteins. EMBO J. 1999;18:3064–3073. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.11.3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gires O, Zimber-Strobl U, Gonnella R, Ueffing M, Marschall G, Zeidler R, Pich D, Hammerschmidt W. Latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus mimics a constitutively active receptor molecule. EMBO J. 1997;16:6131–6140. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson S, Rowe M, Gregory C, Croom-Carter D, Wang F, Longnecker R, Kieff E, Rickinson A. Induction of bcl-2 expression by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 protects infected B cells from programmed cell death. Cell. 1991;65:1107–1115. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90007-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huen D S, Henderson S A, Croom-Carter S, Rowe M. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 (LMP1) mediates activation of NF-κB and cell surface phenotype via two effector regions in its carboxy-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Oncogene. 1995;10:549–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Izumi K, Kieff E. The Epstein-Barr virus oncogene product latent membrane protein 1 engages the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated death domain protein to mediate B-lymphocyte growth transformation and activate NF-κB. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12592–12597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Izumi K M, Kaye K M, Kieff E D. The Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 amino acid sequence that engages tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factors is critical for primary B lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1447–1452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Izumi K M, McFarland E C, Ting A T, Riley E A, Seed B, Kieff E D. The Epstein-Barr virus oncoprotein latent membrane protein 1 engages the tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated proteins TRADD and receptor-interacting protein (RIP) but does not induce apoptosis or require RIP for NF-κB activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5759–5767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.8.5759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaye K M, Izumi K M, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is essential for B-lymphocyte growth transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9150–9154. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaye K M, Izumi K M, Li H, Johannsen E, Davidson D, Longnecker R, Kieff E. An Epstein-Barr virus that expresses only the first 231 LMP1 amino acids efficiently initiates primary B-lymphocyte growth transformation. J Virol. 1999;73:10525–10530. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10525-10530.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus and its replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippinscott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2343–2396. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kieser A, Kilger E, Gires O, Ueffing M, Kolch W, Hammerschmidt W. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein-1 triggers AP-1 activity via the c-Jun N-terminal kinase cascade. EMBO J. 1997;16:6478–6485. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kilger E, Kieser A, Baumann M, Hammerschmidt W. Epstein-Barr virus-mediated B-cell proliferation is dependent upon latent membrane protein 1, which simulates an activated CD40 receptor. EMBO J. 1998;17:1700–1709. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.6.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruh J. Effects of sodium butyrate, a new pharmacological agent, on cells in culture. Mol Cell Biochem. 1982;42:65–82. doi: 10.1007/BF00222695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liebowitz D, Wang D, Kieff E. Orientation and patching of the latent infection membrane protein encoded by Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1986;58:233–237. doi: 10.1128/jvi.58.1.233-237.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu R, Au W C, Yeow W S, Hageman N, Pitha P M. Regulation of the promoter activity of interferon regulatory factor-7 gene. Activation by interferon and silencing by hypermethylation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31805–31812. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005288200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marie I, Durbin J E, Levy D E. Differential viral induction of distinct interferon-alpha genes by positive feedback through interferon regulatory factor-7. EMBO J. 1998;17:6660–6669. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller W, Cheshire J, Raab-Traub N. Interaction of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor signaling proteins with the latent membrane protein 1 PXQXT motif is essential for induction of epidermal growth factor receptor expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2835–2844. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller W E, Earp H S, Raab-Traub N. The Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 induces expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Virol. 1995;69:4390–4398. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4390-4398.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller W E, Mosialos G, Kieff E, Raab-Traub N. Epstein-Barr virus LMP1 induction of the EGFR is mediated through a TRAF signaling pathway distinct from NF-κB activation. J Virol. 1997;71:586–594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.586-594.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitchell T, Sugden B. Stimulation of NF-κB-mediated transcription by mutant derivatives of the latent membrane protein of Epstein-Barr virus. J Virol. 1995;69:2968–2976. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.5.2968-2976.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murono S, Inoue H, Tanabe T, Joab I, Yoshizaki T, Furukawa M, Pagano J S. Induction of cycloxygenase-2 by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1 is involved in vascular endothelial growth factor production in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6905–6910. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121016998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pagano J S. Epstein-Barr virus. In: David Humes H, editor. Kelley's textbook of internal medicine. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott, Williamson and Wilkins; 2000. pp. 2181–2185. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pagano J S. Epstein-Barr virus: the first human tumor virus and its role in cancer. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1999;111:573–580. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1381.1999.t01-1-99220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raab-Traub N. Pathogenesis of Epstein-Barr virus and its associated malignancies. Semin Virol. 1996;7:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragona G, Ernberg I, Klein G. Induction and biological characterization of the Epstein-Barr virus carried by the Jijoye lymphoma cell line. Virology. 1980;101:553–557. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(80)90473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rickinson A B, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippinscott-Raven Publishers; 1996. pp. 2397–2446. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandberg M, Hammerschmidt W, Sugden B. Characterization of LMP1's association with TRAF1, TRAF2, and TRAF3. J Virol. 1997;71:4649–4656. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4649-4656.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sato M, Suemori H, Hata N, Asagiri M, Ogasawara K, Nakao K, Nakaya T, Katsuki M, Noguchi S, Tanaka N, Taniguchi T. Distinct and essential roles of transcription factors IRF-3 and IRF-7 in response to viruses for IFN-alpha/beta gene induction. Immunity. 2000;13:539–548. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson W C, Deanin G G, Gordon M W. Intact microtubules are required for rapid turnover of carboxyl-terminal tyrosine of alpha-tubulin in cell cultures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1318–1322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.3.1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, Leibowitz D, Kieff E. An EBV membrane protein expressed in immortalized lymphocytes transforms established rodent cells. Cell. 1985;43:831–840. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang F, Gregory C, Sample C, Rowe M, Liebowitz D, Murray R, Rickinson A, Kieff E. Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein (LMP1) and nuclear proteins 2 and 3C are effectors of phenotypic changes in B lymphocytes: EBNA-2 and LMP1 cooperatively induce CD23. J Virol. 1990;64:2309–2318. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2309-2318.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watanabe N, Sakakibara J, Hovanessian A G, Taniguchi T, Fujita T. Activation of IFN-beta element by IRF-1 requires a posttranslational event in addition to IRF-1 synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4421–4428. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wathelet M G, Lin C H, Parekh B S, Ronco L V, Howley P M, Maniatis T. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-beta enhancer in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshizaki T, Sato H, Furukawa M, Pagano J S. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 is enhanced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3621–3626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang L. Gradient temperature hybridization using a thermocycler for RNase protection assays. Mol Bio/Technol. 2000;14:73–75. doi: 10.1385/MB:14:1:73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang L, Pagano J S. Interferon regulatory factor 2 represses Epstein-Barr virus BamhI Q latency promoter in type III latency. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3216–3223. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.3216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Pagano J S. Interferon regulatory factor 7 is induced by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J Virol. 2000;74:5748–5757. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.3.1061-1068.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang L, Pagano J S. Interferon regulatory factor 7 mediates the activation of Tap-2 by Epstein-Barr virus latent membrane protein 1. J Virol. 2001;75:341–350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.341-350.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang L, Pagano J S. IRF-7, a new interferon regulatory factor associated with Epstein-Barr virus latency. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5748–5757. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.5748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]