NF-κB Family of Transcription Factors: Central Regulators of Innate and Adaptive Immune Functions (original) (raw)

Abstract

Transcription factors of the Rel/NF-κB family are activated in response to signals that lead to cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis, and these proteins are critical elements involved in the regulation of immune responses. The conservation of this family of transcription factors in many phyla and their association with antimicrobial responses indicate their central role in the regulation of innate immunity. This is illustrated by the association of homologues of NF-κB, and their regulatory proteins, with resistance to infection in insects and plants (M. S. Dushay, B. Asling, and D. Hultmark, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA **93:**10343-10347, 1996; D. Hultmark, Trends Genet. **9:**178-183, 1993; J. Ryals et al., Plant Cell **9:**425-439, 1997). The aim of this review is to provide a background on the biology of NF-κB and to highlight areas of the innate and adaptive immune response in which these transcription factors have a key regulatory function and to review what is currently known about their roles in resistance to infection, the host-pathogen interaction, and development of human disease.

INTRODUCTION

In mammals the NF-κB family of transcription factors contains five members: NF-κB1 (p105/p50), NF-κB2 (p100/p52), RelA (p65), RelB, and c-Rel (Fig. 1). NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 are synthesized as large polypeptides that are posttranslationally cleaved to generate the DNA binding subunits p50 and p52, respectively. Members of the NF-κB family are characterized by the presence of a Rel homology domain (Fig. 1) which contains a nuclear localization sequence and is involved in sequence-specific DNA binding, dimerization, and interaction with the inhibitory IκB proteins (67). The NF-κB members dimerize to form homo- or heterodimers, which are associated with specific responses to different stimuli and differential effects on transcription. NF-κB1 (p50) and NF-κB2 (p52) lack transcriptional activation domains, and their homodimers are thought to act as repressors. In contrast, Rel-A, Rel-B, and c-Rel carry transcriptional activation domains, and with the exception of Rel-B, they are able to form homo- and heterodimers with the other members of this family of proteins. The balance between different NF-κB homo- and heterodimers will determine which dimers are bound to specific κB sites and thereby regulate the level of transcriptional activity. In addition, these proteins are expressed in a cell- and tissue-specific pattern that provides an additional level of regulation. For example, NF-κB1 (p50) and RelA are ubiquitously expressed, and the p50/RelA heterodimers constitute the most common inducible NF-κB binding activity. In contrast, NF-κB2, Rel-B, and c-Rel are expressed specifically in lymphoid cells and tissues.

FIG. 1.

Members of the Rel/NF-κB and IκB families of proteins. The arrows indicate the endoproteolytic cleavage sites of p105 and p100 which give rise to p50 and p52, respectively. Black boxes indicate the PEST domains, shaded boxes on Bcl-3 indicate transactivation domains, and gray boxes on RelB indicate leucine zipper domains. Abbreviations: RHD, Rel homology domain; ANK, ankyrin repeat; SS, signal-induced phosphorylation sites.

In unstimulated cells, NF-κB dimers are retained in the cytoplasm in an inactive form as a consequence of their association with members of another family of proteins called IκB (inhibitors of κB). The IκB family of proteins includes IκBα, IκBβ, IκBɛ, Bcl-3, and the carboxyl-terminal regions of NF-κB1 (p105) and NF-κB2 (p100) (Fig. 1). Recent studies have also identified a novel family member, IκBζ, that is thought to act in the nucleus (219). The IκB proteins bind with different affinities and specificities to NF-κB dimers. Thus, not only are there different NF-κB dimers in a specific cell type, but the large number of combinations between IκB and NF-κB dimers illustrates the sophistication of the system.

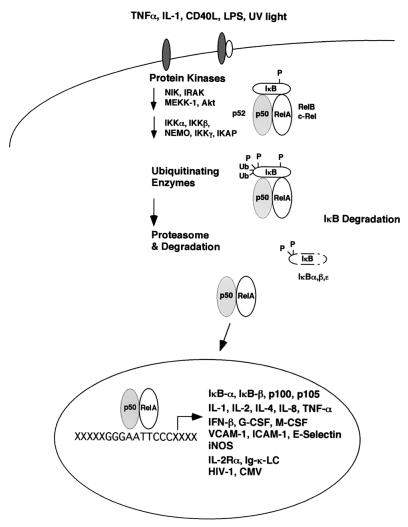

Although several non-receptor-mediated pathways (such as oxidative stress or UV irradiation) lead to activation of NF-κB, it is the receptor-mediated events which result in activation of these transcription factors that have been best characterized (Fig. 2). The binding of a ligand (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α], interleukin 1 [IL-1], CD40L, lipopolysaccharide [LPS]) to its receptor triggers a series of events involving protein kinases that result in the recruitment and activation of the IκB kinases (IKKs) that phosphorylate IκB. There are at least three components of this signalsome complex—IKKα, IKKβ, and NEMO/IKKγ—which together provide an additional level of regulation that controls gene transcription. Thus, several studies indicate that IKKβ is the target of proinflammatory stimuli, whereas IKKα may be more important in morphogenic signals (40, 90, 123, 193), although there is evidence that IKKα is involved in lymphotoxin-mediated signaling (131).

FIG. 2.

In unstimulated cells, the Rel/NF-κB homo- and heterodimers associate with members of the family of inhibitor proteins called IκB and remain as an inactive pool in the cytoplasm. Upon stimulation by different agents like IL-1, TNF-α, CD40L, LPS, or UV light, IκB molecules are rapidly phosphorylated, ubiquitinated, and degraded, allowing the NF-κB dimers to translocate to the nucleus and regulate transcription through binding to κB sites.

The phosphorylation of two serine residues at the NH2 terminus of IκB molecules, for example, Ser32 and Ser36 in IκBα, leads to the polyubiquitination on Lys21 and Lys22 of IκBα and subsequent degradation of the tagged molecule by the 26S proteasome (for a review see reference 108 and the work of D. M. Rothwarf and M. Karin [www.stke.org/cgi/content/full/OC_sigtrans;1999/5/re1]). The degradation of IκB exposes the nuclear localization sequence and allows NF-κB dimers to translocate to the nucleus, bind to κB motifs present in the promoters of many genes, and regulate transcription. As part of an autocrine loop, the binding of NF-κB will induce transcription of IκB genes and so provide a mechanism for limiting the activation of NF-κB activity (21, 189). In this system, the activation of NF-κB is independent of de novo protein synthesis and so allows a rapid response to appropriate stimuli. Recent studies have also shown that while IKKβ is required for inducible phosphorylation-dependent degradation of IκB, IKKα is not. Instead, it appears that IKKα preferentially phosphorylates NF-κB2, and this is required for the processing of the p100 NF-κB2 precursor (178).

Given the functional and structural similarities of the different family members (Fig. 1), a major question about these transcription factors is the extent to which different NF-κB members are interchangeable and can functionally compensate for each other. For example, NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 are highly conserved, but mice deficient in either of these genes develop normally. In contrast, mutant mice which lack both of these genes have a blockage in osteoclast differentiation, leading to defects in bone remodeling and osteopetrosis (60, 98). These findings suggest that complexes which contain NF-κB1 or NF-κB2 can compensate for each other. Similarly, complexes which contain NF-κB1 can partially compensate for the loss of RelB (209), and a similar conclusion has been reached for RelA and c-Rel (discussed below). However, in many of these types of studies it is difficult to distinguish between the effects of redundancy, complementary pathways, and simply cumulative effects of gene deletions.

NF-κB AND REGULATION OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM

Pro- and Antiapoptotic Functions of NF-κB

Apoptosis is an important process which regulates the development and selection of T and B lymphocytes and is critical for the maintenance of immunological homeostasis in the periphery. The activation of NF-κB is strongly linked to the inhibition of apoptosis (13, 133, 200, 203), likely due to the ability of NF-κB to regulate expression of antiapoptotic genes such as TRAF1, TRAF2, c-IAP1, cIAP2, IEX-1L, Bcl-xL, and Bfl-1/A1 (75, 111, 202, 214, 230). Perhaps the best example of the role of NF-κB in resistance to apoptosis is provided by in vitro studies which showed that loss of RelA renders embryonic fibroblasts more susceptible to TNF-induced apoptosis and in vivo studies in which RelA−/− mice die as embryos as a consequence of the TNF-mediated apoptosis in the livers of these animals (3, 12, 43). Although most studies link NF-κB with prevention of apoptosis, NF-κB has also been associated with proapoptotic functions such as the apoptosis of double-positive thymocytes (82) and with increased expression of the proapoptotic proteins Fas and FasL (109, 152, 195). Moreover, in other experimental systems increased levels of NF-κB activation during development of avian embryos and in focal cerebral ischemia have been correlated with apoptosis (1, 172), but it is difficult to determine whether the increased NF-κB activity observed is a cause or consequence of apoptosis.

Development

The availability of NF-κB−/− cells and NF-κB−/− mice has helped to define the role of specific NF-κB proteins in development and function of immune cells. As mentioned above, RelA is essential to prevent TNF-mediated apoptosis in the liver of the developing fetus, but RelA is not required for the development of T and B cells, as the transfer of fetal liver cells from RelA−/− mice to irradiated SCID mice leads to normal lymphocyte development (44). It appears that signaling through IKKβ is essential to protect T cells from TNF-α-induced apoptosis during development (178). The comparison of RelA−/− mice with mice deficient in both RelA and c-Rel indicates that c-Rel can partially compensate for the absence of RelA in the liver. For instance, the transfer of fetal liver cells from RelA−/− c-Rel−/− mice to irradiated recipients results in the development of all hematopoietic lineages, but the number of differentiated cells is lower than expected, and these mice have impaired erythropoiesis and dysregulated granulopoiesis which results in their death (71).

The role of NF-κB in the development of dendritic cells is illustrated by the lack of CD8α− and thymic dendritic cells in RelB−/− mice (20, 211) and the lack of follicular dendritic cells in the absence of NF-κB2 (25, 157). Although the lack of thymic dendritic cells in RelB−/− mice is an indirect consequence of a defect in thymic epithelia (212), the lack of other dendritic cell populations in the RelB−/− and NF−κB2−/− mice could be due to specific blocks in the development or the maturation processes that give rise to these subsets (144). Indeed, previous studies have shown that inhibitors of NF-κB activation block maturation of dendritic cells (160).

The role of NF-κB in T-cell development and selection is illustrated by the transgenic expression of a degradation-deficient form of IκBα (ΔIκB) in T cells. Because this mutant protein is not normally degraded in response to signals that activate NF-κB, it acts as a global inhibitor of this signaling pathway. Several groups have generated similar transgenic mice, and while there are some differences between these mice, their phenotypes have included decreased thymic cellularity, reduced numbers of peripheral CD8+ T cells, and increased levels of apoptosis (19, 53, 54). Although individual NF-κB proteins are not essential for the development of conventional mature B cells, IKKα is essential for B-cell development and function (106). The finding that IKKα is required for the processing of NF-κB2 (178) may partially explain this defect since NF-κB2−/− mice have approximately 10% of normal B-cell numbers (27, 58). In mice which lack both NF-κB1 and NF-κB2, B-cell maturation is blocked at the immature stage, although it is not known if this is due to a cell autonomous defect (60) or whether factors like the TNF superfamily member BlyS, which activate NF-κB (107) and are important in the control of B-cell homeostasis, are dysregulated in these mice. Marginal zone B cells represent a subset of B cells localized in the marginal sinuses of the spleen and are thought to be the one of the first immune cells that interact with blood-borne pathogens and so may represent a link between innate and adaptive immunity. In several of the NF-κB−/− mice, the numbers of marginal zone B cells are reduced, and in RelB−/− and NF-κB1−/− mice, this subset is completely absent (30, 207).

Homeostasis and Lymphoid Architecture

The analysis of mice deficient in various NF-κB family members has revealed an important role for these transcription factors in the maintenance of immune homeostasis and control of lymphoid architecture. Examples of this are provided by RelB−/− mice which have enlarged spleens, extramedullary hematopoesis, and defects in germinal center formation (207, 208). In addition, these mice develop a T-cell-mediated inflammatory disease which results in the death of these mice by 8 to 12 weeks after birth (22, 208). One possible explanation for this phenotype is that in the absence of RelB there is overproduction of chemokines (215), although other studies suggest that these mice have a defect in their ability to produce homing chemokines associated with normal development of splenic architecture (207). Similarly, mice deficient in NF-κB2 or Bcl-3 have major defects in splenic microarchitecture (27, 58, 59), and RelA has recently been shown to be important in the development of Peyer's patches and lymph nodes (2). A deletion of the carboxy-terminal ankyrin repeats of NF-κB1 results in increased κB binding activity of p50 complexes and an inflammatory phenotype composed of lymphocytic infiltration of the lungs and liver (100). A similar deletion of the NF-κB2 protein generates mice with high levels of active p52 complexes, and these mice develop gastric hyperplasia and lymphoproliferation and overproduce IL-2, IL-4, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (99). Mice deficient in c-Rel do not develop obvious pathology (115, 125), but mice with a mutation in the c-Rel transcriptional activation domain develop lymphoid hyperplasia and extramedullary hematopoiesis (31). A major challenge to understanding the basis for the inflammation in these mutant mice is to distinguish whether the phenotypes observed are a consequence of altered cell survival or due to other roles for NF-κB in the maintenance of immunological homeostasis and whether there is a level of compensation between different NF-κB members. Similar questions exist in trying to distinguish distinct roles for the IκB proteins, and studies using transgenic and gene knockout mice have helped to address some of these issues. Thus, IκBα-deficient mice have a high constitutive κB binding activity in several tissues and develop severe defects that result in death at postnatal day 8 (14). In contrast, experiments in which IκBβ was expressed under the control of the IκBα promoter allowed Iκβα-deficient mice to develop normally (36). While these results demonstrate the importance of the IκB system for the regulation of NF-κB, they suggest that rather than each IκB member having a unique set of physical properties that underlies its function, the divergent expression and regulation of the IκB molecules are what account for their distinct roles in the regulation of NF-κB activity.

Innate Immunity

The activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB have been associated with increased transcription of a number of different genes, including those coding for chemokines (IL-8), adhesion molecules (endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule, vascular cell adhesion molecule, and intercellular adhesion molecule), and cytokines (IL-1, IL-2, TNF-α, and IL-12). These immune mediators are important components of the innate immune response to invading microorganisms and are required for the ability of inflammatory cells to migrate into areas where NF-κB is being activated. The types of signals most commonly associated with activation of NF-κB are those which are a consequence of inflammation and infection. There is an extensive list of bacteria—including Mycobacterium tuberculosis (196), Borrelia burgdorferi (51), and Neisseria gonorrhea I (141)—and bacterial products, such as LPS (63) and Shiga toxin (128), which can activate NF-κB in macrophages as well as other cell types. In addition, many studies link the ability to activate NF-κB with the regulation of genes involved in immunity. Thus, enteroinvasive bacteria have been shown to activate NF-κB in intestinal epithelial cells, a process which leads to increased production of inflammatory mediators such as chemokines (MCP-1 and IL-8) as well as TNF-α, intercellular adhesion molecule, and cyclooxygenase 2 (52). Similarly, other bacterial infections, including scrub typhus, Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Helicobacter pylori, have been shown to lead to the NF-κB-dependent induction of chemokines (37, 134, 136). These types of NF-κB-dependent responses are not restricted to bacteria; invasion of endothelial cells by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma cruzi also activates NF-κB, and this is associated with increased expression of several adhesion molecules (91). There are also indirect pathways that lead to NF-κB activation, and this is illustrated by studies in which infection of pulmonary epithelial cells with M. tuberculosis results in the release of IL-1, which in turn can activate the NF-κB pathway required for the production of the chemokine IL-8 (211).

While it has been recognized that many bacterial products can activate NF-κB, the identification of the Toll-like receptors (TLRs) as specific pattern recognition molecules (132) and the recognition that stimulation of these receptors led to activation of NF-κβ were important steps in understanding how many different pathogens could stimulate cells to activate NF-κB. A role for Toll receptors in innate immunity to infection was first described in _Drosophila melanogaster_AQJ:Drosophila melanogaster correct? (120, 164), and the identification of multiple TLRs in humans (163) suggests that, as in invertebrates (213), these evolutionarily conserved pattern recognition receptors are an important element of innate immunity. TLRs are distributed widely, and while most studies focus on their role in the activation of accessory cell (macrophage, dendritic cell, B-cell) functions, there is evidence that some TLRs are also present on T and NK cells (139). The identification of multiple members of the TLR family and the presence of additional homologues (34) have resulted in many studies to define the specificity of these pattern recognition molecules. Initial studies quickly defined TLR4 as the ligand for the LPS component of gram-negative bacteria (87, 112, 137, 222), and additional studies have linked the recognition of respiratory syncytial virus (117) and heat shock proteins to TLR4 (148). Although TLR2 activates similar pathways to TLR4 (205), TLR2 appears to recognize a larger variety of microbial products, including peptidoglycans and lipoproteins (84, 194). In addition TLR5 has been linked to the recognition of bacterial flagellin (66, 80), TLR9 has been linked to the recognition of bacterial DNA (81), and TLR3 has been linked to the recognition of double-stranded RNA (4). The consequences of signaling through the TLR have been linked to increased expression of a number of genes known to be regulated by NF-κB, including cytokines, costimulatory molecules, nitric oxide, and susceptibility to apoptosis as well as an autocrine increase in Toll expression (5, 20, 126, 132, 146).

Since cells of the monocyte lineage express TLR and represent the major populations involved in cellular innate immunity, their expression of high levels of all NF-κB members (32, 55, 68, 72, 144) indicates their likely role in the function of these cells. Analysis of macrophage populations from c-Rel−/− or RelB−/− mice has identified defects in their functions. Specifically, macrophages from RelB−/− mice are deficient in their ability to produce TNF-α (210) and can produce normal levels of IL-6, IL-10, and IL-12 but overproduce IL-1β (25). Macrophages from c-Rel−/− mice overproduce GM-CSF and IL-6 but have a reduced ability to produce TNF-α (71). The activation of macrophages to produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates is important in the control of many bacterial and parasitic infections. This is a complex process in which gamma interferon (IFN-γ) is important for the activation of macrophages but alone is not normally sufficient to activate macrophages to kill intracellular organisms. Additional cofactors, such as TNF-α, LPS, or signaling through CD40, are required to provide a second signal for macrophage activation. These second signals activate NF-κB, and it has been shown that the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase is regulated by NF-κB and that c-Rel is involved in this process (71, 216).

IL-12 is one of the most-important cytokines involved in the activation of innate and adaptive responses to intracellular infections. Its production in response to numerous intracellular organisms leads to the innate activation of NK cells and enhances their cytolytic activity and production of IFN-γ (175). These innate events are important in resistance to many different viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections and provide a nonspecific mechanism of resistance prior to the development of an adaptive immune response (17).

The link of IL-12 to the NF-κB family of transcription factors was shown by studies in which the IL-12 p40 promoter was demonstrated to have NF-κB binding sites that are involved in production of IL-12 (69, 138, 224). Using macrophages from NF-κB−/− mice, Sanjabi et al. showed that c-Rel and Rel-A are both important in the LPS-induced production of IL-12 by macrophages (169), although NF-κB1 and NF-κB2 or RelB appear to have no major role in the ability of macrophages to respond to LPS (25, 26, 169). These studies have been expanded by Grumont et al. to show that c-Rel also plays a role in the ability of CD8α+ dendritic cells to make p35 but not p40 (73). Whether different stimuli that induce IL-12 have different requirements for specific NF-κB members is unknown, but recent studies indicate that there are c-Rel-independent pathways that lead to the production of IL-12 (130).

Although monocytes and macrophages constitute a major arm of the innate immune system, there are other cell types which play an important role in the initial recognition of many pathogens and which may also provide effector activities. Nonimmune cells such as fibroblasts endothelial and epithelial cells are also capable of responding to pathogens by activating NF-κB, which has been implicated in the induction of chemokine production. Recently it has been shown that fibroblasts can respond to necrotic cells in a TLR2-dependent fashion to activate NF-κB and the production of chemokines (122). The latter studies provide a mechanism that allows the immune system to recognize the presence of pathogens that cause cellular necrosis. The ability of neutrophils, mast cells, and eosinophils to recognize a diverse array of pathogens is thought to represent an important first line of defense against infection. However, much less is known about the role of NF-κB in the regulation of these innate responses, although there is increased interest in defining how this pathway may be involved in the functions of these cells. This is illustrated by recent studies in which it was shown that TNF-α-mediated activation of NF-κB delays neutrophil apoptosis (206) and so may provide a survival signal to neutrophils at a local site of infection which allows them to mediate their antimicrobial activities. Additional studies have shown that NF-κB is involved in the ability of mast cells to make the T-cell and mast-cell growth factor IL-9 (187) and that their expression of TLR4 plays a critical role in the recruitment of neutrophils and protection from enterobacterial infection (191).

Although many pathogens can stimulate activation of NF-κB, there are other immune molecules associated with innate immunity which activate NF-κB. Stimuli such as IL-1, IL-18, TNF-α, and signaling through CD28 lead to activation of NF-κB, and these signals can augment the innate ability of NK cells to produce IFN-γ (61, 96, 97, 140, 182, 197, 226). Since all of these cofactors are associated with activation of NF-κB and there are NF-κB sites in the promoter for IFN-γ (183), it is likely that maximal activation of NK cells to produce IFN-γ would be dependent on NF-κB, and this argument is supported by studies in which NK cells from mice which lack RelB have a defect in their ability to produce IFN-γ (25). Thus, activation of NF-κB not only is associated with the recognition of an invading microorganism but also is associated with regulation of the subsequent immune response. Together, these studies associate activation of NF-κB with initial recognition of multiple pathogens, microbicidal mechanisms of macrophages, production of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, and activation of NK cells to produce IFN-γ. As a consequence, NF-κB is implicated in many aspects of innate resistance to infection, and studies are now needed to delineate its role in different types of infection.

T-Cell Activation and Effector Function

Many of the events that are important in triggering innate resistance to infection are also important for the development of protective T-cell responses. Thus, the abilities of accessory cells to present antigen, provide costimulation, and produce cytokines in response to infection are critical to the subsequent adaptive immune response. The previous section highlighted the role of NF-κB in the innate production of IL-12, which is critical to direct the development of T-cell responses dominated by the production of IFN-γ. Additional studies have shown a role for NF-κB in other accessory cell functions that are specifically involved in adaptive immunity. For example, RelA is required for the ability of embryonic fibroblasts to express optimal levels of major histocompatibility complex class I and CD40, molecules required for the development of CD8+ T-cell responses (152). Chemical inhibitors of NF-κB activation have been shown to block maturation of dendritic cells, and their ability to upregulate expression of major histocompatibility complex class II and B7 costimulatory molecules, which are also required for efficient CD4+ T-cell responses (160). NF-κB is also involved in regulation of the costimulatory molecule B7h (192), the ligand for the T-cell costimulatory molecule ICOS. Collectively, these studies indicate the importance of NF-κB in the regulation of accessory cell functions which affect adaptive responses.

The expression of most of the NF-κB family members in T cells indicates that they are likely to be involved in T-cell functions. The development of an adaptive T-cell response is balanced by the proliferation and expansion of antigen-specific T cells during the initiation of the response and the loss of excess T cells as a response resolves. In addition, the maintenance of long-term memory cells is the hallmark of adaptive immunity, and NF-κB has recently been implicated in the signals that allow memory to develop. There are many studies which link NF-κB to T-cell proliferation, and there are clear links between the activation of NF-κB and the expression of cyclin D1, which is important in the commitment to DNA synthesis (for a review, see reference 103). Direct evidence for a role of NF-κB in T-cell proliferation from murine models is provided by studies in which transgenic mice were generated which express the degradation-deficient ΔIκB transgene, which acts as a global inhibitor of NF-κB activity, under the control of a T-cell-specific promoter. T cells from these mice have severely impaired proliferative responses (19, 54, 135). Moreover, mice lacking the polypeptide p105 precursor of NF-κB1, but which express p50 (100), as well as c-Rel−/− mice (31, 125) have impaired T-cell proliferative responses. The basis for these proliferative defects is frequently unclear, although there are many potential explanations. Interestingly, recent studies have shown that T cells which express the ΔIκB transgene have a defect in their ability to activate STAT5a, a transcription factor required for T-cell proliferation mediated through IL-2 and IL-4 (135). Another possibility is provided by studies which showed that in mature T cells, signaling through the T-cell receptor (TCR) leads to the activation of protein kinase Cθ and subsequent NF-κB activity (190) which may be important in TCR-mediated proliferative signals. An alternative is that the costimulatory signals which are required for optimal expansion and differentiation of antigen-specific T cells are reduced. Thus, CD28 is a critical costimulatory molecule expressed by T cells which targets IκB kinases (78), leads to activation of c-Rel and NF-κB2 (65, 105), and is important in the expression of the T-cell growth factor IL-2 and the antiapoptotic molecule Bcl-xL (18, 124). The absence or reduction of TCR and costimulatory signals provides a likely explanation for the defects in the ability of T cells which lack NF-κB activity to proliferate.

Trying to understand the role of NF-κB in protection against T-cell apoptosis is complicated by the apparently contradictory data reported in many studies. This variation may be a reflection of the multiple stimuli (TNF-α, Fas, and TCR stimulation) as well as growth factor withdrawal that integrate to remove excess T cells during thymic development as well as at the end of an immune response. Many studies have linked NF-κB and the signaling pathway upstream of NF-κB activation with these events. Thus, IKKα has been shown to be essential for the protection of T cells from TNF-α-mediated apoptosis (179), whereas RelA is essential for TNF-α-induced Fas expression but RelA, c-Rel, and NF-κB1 do not appear to provide significant protection against TCR-mediated activation-induced cell death (228). In contrast, transfection of NF-κB1 and RelA into Jurkat cells (a T-cell leukemic cell line) can protect against Fas-mediated death and in the absence of NF-κB activity T cells are more susceptible to activation-induced cell death (48). To understand the factors that promote T-cell survival during an immune response, Mitchell et al. used a microarray approach to compare gene expressions of T cells activated in vivo with or without the presence of adjuvants (133). These studies revealed that the NF-κB genes Bcl-3 and RelB were upregulated when an adjuvant was used and that retroviral expression of Bcl-3 enhanced survival of activated T cells, thus linking Bcl-3 to the maintenance of T-cell responses. Similarly, in the absence of NF-κB2, mice infected with Toxoplasma gondii fail to maintain their T-cell responses associated with increased levels of apoptosis, but the mechanism that underlies this effect is unknown (26).

The recognition that T-cell responses could be broadly divided into functional subsets of Th1 (dominated by the production of IFN-γ and associated with cell-mediated immunity) or Th2 (characterized by production of IL-4 and IL-5 and associated with humoral immunity) was important because it provided a basis for understanding how T cells contribute to resistance or susceptibility to different types of pathogens. While NF-κB is involved in the production of IL-12 (224) required for the generation of Th1 responses (89), these transcription factors may also play a direct role in the development of polarized T-cell responses. Early studies suggested that although Th1 and Th2 cells expressed similar levels of RelA and c-Rel, Th1 cells could activate RelA in response to TCR stimulation, whereas Th2 cells could not (119). Evidence of a role for NF-κB in the production of IFN-γ by T cells is provided by the description of a functional NF-κB site in the IFN-γ promoter (183) and by studies which linked the ability of IL-18 to activate NF-κB with T-cell production of IFN-γ (114, 162). Moreover, the transgenic expression of the degradation-deficient ΔIκBα mutant in T cells resulted in reduced production of IFN-γ following TCR stimulation (7, 9, 54). That mice deficient in c-Rel or RelB have defects in their ability to produce IFN-γ (25, 65) implicates these two members in the regulation of Th1-cell responses. An alternative model for the regulation of IFN-γ production by NF-κB is provided by studies which have shown that IL-18-induced expression of GADD45β is NF-κB dependent and that GADD45β activates p35 mitogen-activate protein kinase, which is important for the cytokine-induced production of IFN-γ by T cells (220). Regardless of whether NF-κB has a direct or indirect role in the regulation of IFN-γ production there are several in vivo systems which demonstrate a role for NF-κB in disease states in which IFN-γ plays an important role. Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis is an autoimmune condition mediated by a Th1-type T-cell response, and NF-κB1−/− mice are more resistant to the development of this condition (83). Similarly, collagen-induced arthritis is also mediated by Th1 cells, and the inhibition of NF-κB in this experimental system ameliorates this inflammatory disease (64, 176).

While there are many studies that link NF-κB to the development of Th1-type responses, less is known about the role of NF-κB in the regulation of Th2-type responses. In vitro studies have revealed that Th2 cells do activate NF-κB (47, 119) and that the binding of RelA to sites in the IL-4 promoter has been linked to inhibition of NF-AT binding required for IL-4 production (33). Initial studies using transgenic mice which express the ΔIκB mutant in T cells indicated that it did not alter the ability of these mice to develop Th2-type responses in vivo (7), although there was some decrease in their capacity to produce IL-4 upon primary TCR stimulation in vitro (7, 9, 54). Subsequent studies have provided evidence that NF-κB1 is required for development of Th2 responses in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (83) and pulmonary inflammation (221). A potential mechanism that explains the requirement for NF-κB1 inTh2 responses is provided by studies in which it was shown that in the absence of NF-κB1, there is reduced expression of the transcription factor GATA3 (39), which has an important role in differentiation of Th2 cells and their production of IL-4 and IL-5 (153, 227).

The IL-1 family of proteins (IL-1α/β and IL-18) all activate NF-κB and have been associated with development of Th1 responses (see above) as well as Th2 responses (88, 92, 218). Related to those findings are studies which identified the ST2/T1 protein as a homologue of the IL-1 receptor which is able to activate NF-κB (156) and indicated that this protein is a marker of Th2 cells and is required for the development of Th2-mediated responses in models of infection and inflammation (38, 116, 217). However, the generation of mice deficient in ST2/T1 has revealed that this protein is not essential for Th2 responses (86). Evidence that other NF-κB family members are involved in Th2 responses is provided by studies which showed that c-Rel is required for optimal production of IL-4 (127) as well as in the development of Th2-type responses associated with allergic pulmonary inflammation (46). The interpretation of many of the studies which examine the role of NF-κB in Th1 and Th2 development is frequently complicated by the linkage between NF-κB and its role in proliferation and cell survival, which can have a profound influence on the development of Th1 and Th2 responses (159).

B-Cell Activation and Effector Function

The original identification of NF-κB as a nuclear factor able to bind to the κB site in the immunoglobulin kappa light chain enhancer and the presence of constitutive NF-κB activity observed in B cells indicate the importance of NF-κB in the control of B-cell functions (177). This was confirmed by multiple studies in which mice deficient in NF-κB1, NF-κB2, RelA, RelB, c-Rel, or Bcl-3 or in which the ΔIκB mutant was expressed in B cells were shown to have compromised humoral immune responses (15, 27, 44, 58, 59, 79, 115, 174, 180, 210). During B-cell maturation the composition of the κB binding activity changes, with the p50/c-Rel heterodimer being the dominant complex present in mature B cells, consistent with a requirement for NF-κB1 in immunoglobulin class switching (186). The basis for the defects in humoral immunity in the NF-κB-deficient mice is not well understood and may be intrinsic to the B-cell compartment or due to compromised accessory cell or T-cell functions. For example, NF-κB2 has functions in cells of the hemopoietic and nonhemopoietic lineages that regulate splenic microarchitecture (27, 58, 59), and as a consequence of the disrupted splenic architecture and lack of germinal centers, B-cell responses in NF-κB2−/− mice are compromised. There is also a role for RelB in the development of radiation-resistant stromal cells, but not in bone marrow-derived hemopoietic cells, which are required for proper formation of germinal centers (207). c-Rel may also have an indirect role in the regulation of B-cell functions due to its ability to regulate the production of Jagged1, a ligand for Notch receptors, which have a critical role in B-cell proliferation and differentiation (11). Similarly, c-Rel is thought to regulate interferon regulatory factor 4, which is required for the ability of interferons to inhibit B-cell proliferation (74). Nevertheless, there is a direct role for NF-κB in B-cell function, and an understanding of the role of individual family members in B-cell function is provided by studies which showed that NF-κB1 is required for survival of quiescent B cells and, in combination with c-Rel, prevents apoptosis of mitogen-activated B cells. Similarly, c-Rel, RelA, and RelB are necessary for normal proliferative responses upon stimulation through the B-cell receptor, CD40, and LPS (44, 76, 185, 199). Together, these findings indicate that the NF-κB proteins are important regulatory factors that control the ability of B cells to survive, progress through the cell cycle, and mediate their effector functions.

NF-κB AND INFECTION

The studies reviewed in the previous sections identify the NF-κB proteins as being important components of signaling pathways that regulate the development of immune responses and associated effector functions. However, the main function of the immune system is to recognize and deal with pathogens, and although many different pathogens activate NF-κB through receptors such as the those in the TLR family, there is little understanding of the actual role of NF-κB in resistance to infection.

Resistance and Susceptibility to Pathogens

What is clear is that NF-κB is required for resistance to a variety of viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections, and this is clearly illustrated by gene deletion studies. Thus, mice deficient in NF-κB1 are more susceptible to infection with Listeria monocytogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae but have normal responses to Escherichia coli and Haemophilus influenzae (180). Interestingly, mice which lack the carboxy-terminal ankyrin domain of NF-κB1 appear to have a more severe immune defect than mice which lack the whole NF-κB1 gene and are highly susceptible to opportunistic pathogens (100). NF-κB2−/− mice are more susceptible to L. monocytogenes, and although they are resistant to the acute phase of toxoplasmosis, they do have an increased susceptibility to the chronic phase of this infection (58). This is likely the consequence of increased levels of apoptosis in the mice and a loss of T-cell responses necessary for the maintenance of long-term resistance to T. gondii (26). Mice deficient in Bcl-3, a protein involved in the regulation of NF-κB2 activity, are also more susceptible to challenge with L. monocytogenes, S. pneumoniae, and T. gondii (59, 174). Since these are all pathogens for which resistance is dependent on the production of IFN-γ, these findings suggest a critical role for Bcl-3 in the regulation of cell-mediated immunity.

The importance of c-Rel in resistance to infection is shown by studies in which c-Rel−/− mice infected with Leishmania major develop progressive lesions (normally associated with a Th2-type response), whereas wild-type controls were able to resolve their infection (normally associated with a Th1-type response). In these particular studies the basis for this increased susceptibility to L. major was correlated with defects in macrophage function (71). In addition, while infection of c-Rel−/− mice with influenza virus leads to the development of protective cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses, these mice fail to develop the high titers of virus-neutralizing antibodies seen in wild-type mice (79). Thus, although able to control this infection, these mice displayed a slightly slower clearance of virus and were susceptible to rechallenge, which was likely a consequence of the reduced antibody response. Although RelB−/− mice develop a lethal inflammatory disease, limited studies on their response to infection have shown that RelB is required for resistance to lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) as well as L. monocytogenes (210). Subsequent studies demonstrated that RelB−/− mice are also susceptible to toxoplasmosis, and this is associated with an inability of T and NK cells to produce IFN-γ (25). The basis for this defect in the production of IFN-γ is unclear but would provide a likely mechanism for the increased susceptibility to LCMV and L. monocytogenes.

Taken together, these in vivo studies are important because they illustrate the critical role of NF-κB in resistance to many pathogens. However, many of these studies have not been able to determine whether the susceptibility of different NF-κB knockouts is a direct effect of defects in accessory cell, lymphocyte, or effector cell functions. To address these types of questions, recent studies have assessed how the effects of NF-κB inhibition in hepatocytes would affect immunity to L. monocytogenes. In those studies, the expression of the degradation-deficient ΔIκB mutant in hepatocytes results in impaired resistance to L. monocytogenes in the liver, associated with a reduced capacity to recruit inflammatory cells to this local site (118). An elegant study has also used transgenic mice and genetically modified bacteria to show that the ability of L. monocytogenes to activate NF-κB in endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo is dependent on the virulence gene product listeriolysin O (110). These types of in vivo approach will help to identify the factors that lead to NF-κB activation during an immune response and to define the function of NF-κB in the response of particular cell types to different infections and pathological stimuli.

NF-κB and the Host-Pathogen Relationship

While activation of NF-κB occurs in response to many viral and bacterial pathogens (56, 188, 225) and this is frequently associated with the development of protective immunity, some pathogens have developed strategies to interfere with host NF-κB responses. The African swine fever virus, which replicates in macrophages, encodes an IκB-like protein which can bind to RelA and interferes with NF-κB activation (161). Many of the orthopoxviruses also interfere with the regulation of NF-κB, and cowpox virus is capable of inhibiting the degradation of phosphorylated IκB, which may contribute to the pathogenesis of this virus (149). Other examples link the virulence of different bacteria with the ability to inhibit activation of NF-κB. Mycobacterium ulcerans causes a progressive necrotizing lesion associated with a lack of an immune response and, lipoprotein preparations from this pathogen can inhibit TNF-α-induced activation of NF-κB (154). It has been suggested that the ability of this pathogen to subvert TNF-α-induced signaling may contribute to the persistence of this infection and the chronic inflammation it causes. Virulent strains of Yersinia enterocolitica suppress cellular activation of NF-κB, and as a consequence, the expression of TNF-α by infected macrophages is blocked, resulting in cells undergoing apoptosis (167). The mechanism that underlies this inhibitory effect is due to the ability of these organisms to inhibit mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase activity and subsequent activation of IκB kinase (150, 170), likely through the proteolytic activity of YopJ (151). In contrast, invasive shigella activates NF-κB in epithelial cells, whereas noninvasive strains do not (158). It appears that nonpathogenic strains of salmonella inhibit the ubiquitination of IκB and thereby prevent its degradation and so inhibit activation of NF-κB. As a result, commensal bacteria in the gut do not stimulate an inflammatory response and are able to survive in this environment (142).

While the activation of NF-κB is generally associated with the development of protective immunity against infection, there are cases where pathogens use these events to their advantage. The activation of NF-κB is required for the ability of several viruses to express genes and replicate. The identification of two NF-κB binding sites in the enhancer region of the promoter of the long terminal repeat (LTR) gene of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) led to studies which investigated the role of these elements in the pathogenesis of AIDS. Stimuli such as IL-1, TNF-α, and LPS enhanced transcription of the HIV-1 LTR through the induction of NF-κB DNA binding activities (166). Thus, the activation of factors that control the expression of immune response genes enhances the replication of HIV. In addition, in vitro studies indicate that HIV-infected cells have a constitutively activated IKK complex and that the presence of IκBβ in the nucleus helps to maintain NF-κB-DNA complexes and so enhance NF-κB activity (41). Thus, it appears that multiple mechanisms underlie the NF-κB-mediated transcription of HIV. Several other viruses have also devised strategies that take advantage of NF-κB to regulate their replication (for a general review, see reference 85), and hepadnaviruses express a protein which activates NF-κB by interacting with IκBα as well as p105, the NF-κB1 precursor (188).

In vivo correlates of situations in which NF-κB activation is required for viral survival are rare, but studies which used HIV transgenic mice showed that removal of the NF-κB sites in the LTR resulted in decreased rates of proviral gene expression during an inflammatory stimulus (62). Another example is provided by studies with murine encephalomyocarditis virus (EMCV) in which NF-κB1−/− mice infected with this virus are more resistant than wild-type littermates to infection, and this resistance was initially attributed to enhanced production of the type I interferons (180). Subsequent studies confirmed a role for the type I IFN in resistance against EMCV and revealed that NF-κB1−/− cells undergo rapid apoptosis when infected with EMCV, so compromising the ability of EMCV to replicate (173). Thus, in normal mice, NF-κB1 protects infected cells from apoptosis and allows the virus to replicate. In bacterial systems, there is also evidence that activation of NF-κB may represent a bacterial strategy that protects host cells from apoptosis and allows bacterial replication within host cells. Thus, normal macrophages infected with E. coli will support the growth of this organism. However, macrophages deficient in NF-κB activation undergo rapid apoptosis, likely due to TNF-α or reactive oxygen intermediates produced in these cultures (113).

While there is a well-developed literature on the interaction of viral and bacterial pathogens with the NF-κB system, much less is known about whether these types of interactions are important in host-parasite systems. Nevertheless, it has recently been reported that the innate resistance of many cell types to infection with the protozoan parasite T. cruzi correlates with the activation of NF-κB in these cells and that overexpression of an IκBα superinhibitor in epithelial cells enhances parasite replication (77). However, myocytes are one of the main cell types in which this parasite persists for the life of the host, and these cells have a reduced capacity to activate NF-κB in response to infection with T. cruzi. These results associate the ability of T. cruzi to avoid activation of NF-κB with the ability to establish infection and raise the question of whether the activation of NF-κB results in innate resistance to T. cruzi. The actual stimulus for activation of NF-κB in infected cells remains unclear, but recent studies have shown that glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from T. cruzi activate NF-κB through TLR2 (29). In addition, infection with T. cruzi does result in an increase in intracellular calcium levels (23), an event associated with activation of NF-κB.

In contrast to T. cruzi, the parasite Theileria parva, which infects bovine T cells and causes the growth and division of infected cells, has been shown to cause continual degradation of IκBα and IκBβ in these cells (101, 155). This results in continued NF-κB activation associated with enhanced lymphocyte survival and proliferation, which allows T. parva to multiply and survive and provides an insight into the pathogenesis of this oncogenic infection. Following infection of mice with T. gondii there is a large increase in NF-κB activity (25, 181), but in vitro studies have shown that invasion of cells by T. gondii fails to activate NF-κB and that this parasite can actually inhibit nuclear translocation of NF-κB in infected cells (24, 181). The mechanism for this effect is unclear, although it has been shown that in vitro infection with T. gondii does lead to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB (24). It remains unclear at what level NF-κB activity is blocked in infected cells, but the functional consequences of this inhibition are decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines, which presumably represents a strategy for enhanced parasite survival. While most studies that have examined the interaction of parasites with the NF-κB system have focused on intracellular protozoans, there is evidence that the larval stage of the helminth parasite Schistosoma mansoni inhibits the ability of endothelial cells to upregulate adhesion molecule expression by interfering with NF-κB activation in these cells. This may represent a mechanism to inhibit the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lungs as this developmental stage migrates through this site (198).

HUMAN DISEASE AND NF-κB

The previous sections have discussed studies that have focused on experimentally manipulated systems but natural mutations in the pathways that lead to the transcriptional activity of NF-κB have illustrated how defects in the pathways that regulate NF-κB activity can contribute to the development and progression of a diverse range of human diseases. During tumor development, the ability of oncogenic proteins, such as mutant forms of Ras, to transform cells is dependent on NF-κB activity, likely due to its ability to induce proliferation and suppress apoptosis (for a general review, see reference 10). There are also other instances in which increased NF-κB transcriptional activity has been associated with tumor development. For example, genomic rearrangements which lead to the truncation of the NF-κB2 p100 protein and transform it into a constitutive transcriptional activator have been described in a series of B- and T-cell lymphomas (35, 143). There are also reports of Hodgkin lymphomas which present with mutations of the ikbα gene that result in IκBα proteins that are unable to interact with the Rel homology domain of NF-κB family members. As a consequence, the mutant IκBα is unable to hold NF-κB inactive in the cytoplasm, resulting in increased levels of constitutive NF-κB transcriptional activity (104). High levels of NF-κB activity are also found in human squamous cell carcinomas, associated with increased expression of NF-κB-regulated genes, including those coding for the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1α, IL-6, and IL-8, which may contribute to metastatic tumor progression (45). Interestingly, transfection of a degradation-resistant IκBα into cell lines from these tumors inhibited NF-κB activity, reduced tumor cell survival, and decreased their expression of proinflammatory cytokines (49), suggesting that NF-κB may represent a useful target for the management of this cancer.

As stated earlier, IKKγ/NEMO is central to cytokine-induced activation of NF-κB, and its absence completely abolishes activation of NF-κB in response to multiple stimuli. It has recently been discovered that mutations affecting the ikkγ/nemo gene are responsible for a series of genodermatosis syndromes, such as incontinentia pigmenti (IP), ectodermal dysplasia (ED) and related syndromes. Patients present with abnormalities of the skin, hair, nails, teeth, eyes, and central nervous system. The skin lesions evolve through several stages that appear directly after birth as a vesicular rash with massive eosinophilic infiltration. Subsequently, verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions evolve and disappear over time. leaving areas of hyperpigmentation. The gene encoding IKKγ is located on the X chromosome, and full deletion of _IKK_γ results in prenatal lethality in males (184). A large number of IP cases are due to a deletion in the IKKγ/NEMO gene that removes exons 4 to 10. In contrast, milder hypomorphic mutations are present in surviving male patients, mostly affecting exon 10 and markedly reducing NF-κB activation (6). The generation of mice deficient in IKK-γ/NEMO has shown that these mice develop similar phenotypes to those developed by IP patients, including perinatal mortality of males (129, 171). Interestingly, mice which overexpress the glucocorticoid receptor in epithelial tissues developed signs of ED, which correlates with the known inhibitory effect of glucocorticoid signaling on NF-κB activity (157).

Other more subtle defects in IKKγ such as deletions of the zinc finger domain of IKKγ result in hypohidrotic ED immunodeficiency, which has been observed in two families, and additional families have also been described which carry nonconserved missense mutations. Patients from these families are susceptible to bacterial infections, present with low levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and IgA and elevated levels of IgM in serum, and have conical teeth and lack sweat glands (229). A mutation in the stop codon of IKKγ, which generates a protein with an extra 27 amino acids, is responsible for a related syndrome called osteopetrosis lymphoedema ED immunodeficiency. This mutation makes the protein unstable, and these patients have impaired activation of NF-κB following stimulation with TNF-α. In addition, accessory cell responses to stimulation through CD40 or LPS are diminished, and defects in T-cell production of IFN-γ are observed (42).

Genetic defects in members of the TNF receptor superfamily—RANK, downless, and CD40, which signal through NF-κB—have been associated with the development of various bone and immune deficiencies. Activating mutations of RANK which lead to increased NF-κB activity are thought to account for the high levels of bone remodeling associated with familial expansile osteolysis or Paget disease of the bone (93). Mutations affecting the downless gene (DL), or its ligand, ectodysplasin (ED1), result in patients with hypohydrotic ED, who present with hypoplasia or absence of teeth, hair, and sweat glands but do not have primary immunodeficiencies. In contrast, defects in the CD40/CD40L interaction result in a hyper-IgM syndrome associated with a reduced ability of these patients to undergo class switching and are also associated with defects in cell-mediated immunity and susceptibility to intracellular infections (70, 121). XHM-ED is a rare form of X-linked hyper-IgM with hypohidrotic ED syndrome in which expression of CD40, CD40L, DL, and ED1 are normal, and these patients have normal bone density and are not more susceptible to intracellular infections. However, these patients carry mutations in the zinc finger domain of IKKγ, and CD40-mediated signaling in these patients is impaired. Thus, B cells from these individuals failed to undergo immunoglobulin class switching upon CD40L-induced activation in vitro and failed to express CD27, a marker of B-cell memory. Similarly CD40 stimulation of APC leads to an impaired production of TNF-α, while LPS signaling is unaffected (102). Collectively, these data indicate that CD40 and LPS, which both activate NF-κB, use different proteins that interact with subdomains of the carboxy terminus of IKKγ/NEMO. The identification of proteins which interact with IKKγ and the resolution of its structure will help us to understand the role of IKKγ in integrating signals that lead to differential regulation of downstream genes.

Recent studies indicate that mutations affecting the leucine-rich repeat (LRR) region in the carboxy terminus of the NOD2 gene are associated with the development of Crohn's disease, a form of inflammatory bowel disease (94, 147). NOD2 belongs to the Apaf-1/Ced-4 family of apoptosis regulators, and it has been proposed that the LRR region of NOD2 is involved in the recognition of pathogen components and acts as an intracellular TLR which leads to the induction of NF-κB. A mutation in the LRR from Crohn's disease patients that generates a truncated protein is impaired in activating NF-κB following stimulation with LPS. There are several possible explanations that may link this defect with the development of Crohn's disease, including defects in the ability of monocytes to sense intracellular bacteria or produce anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10, which result in an enhanced inflammatory response mediated by the adaptive immune system (147). However, it has been questioned whether NOD2 is an intracellular microbial receptor, and other explanations have been proposed that link NOD2 with the regulation of apoptosis (for a review, see reference 16). Nevertheless, these studies have raised new questions about how the LRR of NOD2 regulates NF-κB and whether other genes associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease also encode proteins involved in innate immune responses and activation of NF-κB.

CONCLUSIONS

The generation of mice deficient in different NF-κB family members has illustrated the important role of these proteins in the maintenance of immune homeostasis as well as T- and B-cell functions and the critical role of different family members in the development of protective immunity to infections. In addition, due to the central role of NF-κB in regulating the expression of a diverse range of proinflammatory cytokines and antiapoptotic proteins, this family of factors has been implicated in the development of inflammatory and allergic diseases as well as in tumor development, and its members represent viable targets for the design of novel strategies to manage these conditions. Indeed, there is evidence that inhibition of NF-κB activity during rheumatoid arthritis (28, 57) or inflammatory bowel disease (145) represents a viable strategy to manage these conditions. It should also be noted that many inhibitors of inflammation, such as IL-10, glucocorticoids, aspirin, and FK506, have profound inhibitory effects on NF-κB activity (201, 204, 223). Nevertheless, the underlying role of specific NF-κB family members in these pathological conditions and immunity to infection is frequently unclear. For example, the lack of NF-κB could directly affect the functions of NK, T, or B cells necessary for protection against infection. Alternatively, since the abilities of accessory cells to present antigen, provide costimulation, and produce cytokines are involved in directing the development of the adaptive response, alterations in NF-κB activity in these cells could lead to inappropriate lymphocyte responses and increased susceptibility to infection or development of immune-mediated pathology. In addition, the structural and functional similarity between the different NF-κB family members has led to the idea that for many functions, these factors are essentially interchangeable. Nevertheless, it is clear from the phenotypes of NF-κB-deficient mice that, in many cases, the absence of one of these proteins cannot be fully compensated for by the remaining members of the family, illustrating that individual NF-κB proteins do have unique functions (Table 1). One of the real challenges to understanding the role of NF-κB in regulation of immunity is to be able to dissect the roles of specific NF-κB members in the different regulatory and effector functions essential to coordinate the development of protective immunity to invading microorganisms. In addition, there is a need to understand how (or if) different signals that initiate immunity are integrated to provide pathogen-specific responses or whether the activation of NF-κB leads to a limited number of responses that are normally sufficient to cope with infection. Alternatively, the diverse biology of different pathogens may be critical in influencing the patterns and kinetics of NF-κB activity and thereby play a more important role in directing development of subsequent immune responses.

TABLE 1.

Major phenotypes associated with deletion of NF-κB family membersa

| Phenotype | Description |

|---|---|

| NF-κB1−/− | Defects in production of Ab and T-cell proliferative responses. Absence of marginal zone B cells. Defect in Th2 responses. Increased susceptibility to S. pneumoniae and L. monocytogenes. Normal response to E. coli infection and H. influenzae but enhanced resistance to EMCV. |

| NF-κB2−/− | Disorganized B- and T-cell areas in spleen and lymph nodes associated with absence of marginal zone macrophages and follicular DC. Reduced numbers of B cells and decreased production of antigen-specific Ab. Increased susceptibility to T. gondii, L. monocytogenes, and L. major but normal response to LCMV. |

| NF-κB1−/− NFκB2−/− | Increased mortality after birth and developmental defects including osteopetrosis, thymic and lymph node atrophy, and disorganized splenic structure. |

| Re1A−/− | Embryonic lethality at day 15 to 16 of gestation due to widespread apoptosis of liver parenchymal cells mediated by TNF. Required for formation of secondary lymphoid organs. |

| RelB−/− | Development of lethal T-cell-mediated inflammatory disease. Impaired production of antigen-specific Ab associated with defects in germinal center formation. Lack of marginal zone B cells and thymic and CD8α− DC. Susceptible to L. monocytogenes, LCMV, and T. gondii. Reduced capacity to produce IFN-γ and impaired DTH responses. |

| c-Rel−/− | Impaired T- and B-cell proliferation and reduced Ab responses. Increased susceptibility to L. major and T. gondii. Memory response to influenza virus is impaired. Decreased production of IL-2, IL-3, IL-12, IFN-γ, and GM-CSF. |

| IκBα−/− | Postnatal lethality 7 to 10 days after birth associated with widespread psoriasis-like dermatitis, increased granulopoiesis, and histological alterations in liver and spleen. |

| Bcl-3−/− | Disorganized B- and T-cell areas in spleen. Impaired formation of germinal centers and production of antigen-specific Ab. Defective antigen-dependent priming of T cells. Increased susceptibility to L. monocytogenes, S. pneumoniae, and T. gondii but normal response to E. coli infection. |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants 41158 and 46288 and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund New Initiatives in Malaria Research.

We thank the members of the NF-κB Discussion Group for critical comments during the preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbadie, C., N. Kabrun, F. Bouali, J. Smardova, D. Stehelin, B. Vandenbunder, and P. J. Enrietto. 1993. High levels of c-rel expression are associated with programmed cell death in the developing avian embryo and in bone marrow cells in vitro. Cell 75**:**899-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcamo, E., N. Hacohen, L. C. Schulte, P. D. Rennert, R. O. Hynes, and D. Baltimore. 2002. Requirement for the NF-κB family member RelA in the development of secondary lymphoid organs. J. Exp. Med. 195**:**233-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcamo, E., J. P. Mizgerd, B. H. Horwitz, R. Bronson, A. A. Beg, M. Scott, C. M. Doerschuk, R. O. Hynes, and D. Baltimore. 2001. Targeted mutation of TNF receptor I rescues the RelA-deficient mouse and reveals a critical role for NF-kB in leukocyte recruitment. J. Immunol. 167**:**1592-1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexopoulou, L., A. C. Holt, R. Medzhitov, and R. A. Flavell. 2001. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-κB by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature 413**:**732-738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aliprantis, A. O., R. B. Yang, M. R. Mark, S. Suggett, B. Devaux, J. D. Radolf, G. R. Klimpel, P. Godowski, and A. Zychlinsky. 1999. Cell activation and apoptosis by bacterial lipoproteins through toll-like receptor-2. Science 285**:**736-739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aradhya, S., G. Courtois, A. Rajkovic, R. Lewis, M. Levy, A. Israel, and D. Nelson. 2001. Atypical forms of incontinentia pigmenti in male individuals result from mutations of a cytosine tract in exon 10 of NEMO (IKK-γ). Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68**:**765-771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aronica, M. A., A. L. Mora, D. B. Mitchell, P. W. Finn, J. E. Johnson, J. R. Sheller, and M. R. Boothby. 1999. Preferential role for NF-κB/Rel signaling in the type 1 but not type 2 T cell-dependent immune response in vivo. J. Immunol. 163**:**5116-5124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Attar, R. M., J. Caamano, D. Carrasco, V. Iotsova, H. Ishikawa, R. P. Ryseck, F. Weih, and R. Bravo. 1997. Genetic approaches to study Rel/NF-κB/IκB function in mice. Semin. Cancer Biol. 8**:**93-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aune, T. M., A. L. Mora, S. Kim, M. Boothby, and A. H. Lichtman. 1999. Costimulation reverses the defect in IL-2 but not effector cytokine production by T cells with impaired IκBα degradation. J. Immunol. 162**:**5805-5812. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldwin, A. S., Jr. 2001. The transcription factor NF-kappaB and human disease. J. Clin. Investig. 107**:**3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bash, J., W. X. Zong, S. Banga, A. Rivera, D. W. Ballard, Y. Ron, and C. Gelinas. 1999. Rel/NF-κB can trigger the Notch signaling pathway by inducing the expression of Jagged1, a ligand for Notch receptors. EMBO J. 18**:**2803-2811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beg, A., W. Sha, R. Bronson, S. Ghosh, and D. Baltimore. 1995. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-κB. Nature 376**:**167-170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beg, A. A., and D. Baltimore. 1996. An essential role for NF-κB in preventing TNF-α-induced cell death. Science 274**:**782-784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beg, A. A., W. C. Sha, R. T. Bronson, and D. Baltimore. 1995. Constitutive NF-κB activation, enhanced granulopoiesis, and neonatal lethality in IκBα-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 9**:**2736-2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bendall, H. H., M. L. Sikes, D. W. Ballard, and E. M. Oltz. 1999. An intact NF-κB signaling pathway is required for maintenance of mature B cell subsets. Mol. Immunol. 36**:**187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beutler, B. 2001. Autoimmunity and apoptosis: the Crohn's connection. Immunity 15**:**5-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biron, C. A., and R. T. Gazzinelli. 1995. Effects of IL-12 on immune responses to microbial infections: a key mediator in regulating disease outcome. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 7**:**485-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boise, L. H., A. J. Minn, P. J. Noel, C. H. June, M. A. Accavitti, T. Lindsten, and C. B. Thompson. 1995. CD28 costimulation can promote T cell survival by enhancing the expression of Bcl-xL. Immunity 3**:**87-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boothby, M. R., A. L. Mora, D. C. Scherer, J. A. Brockman, and D. W. Ballard. 1997. Perturbation of the T lymphocyte lineage in transgenic mice expressing a constitutive repressor of nuclear factor (NF-κB). J. Exp. Med. 185**:**1897-1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brightbill, H. D., D. H. Libraty, S. R. Krutzik, R. B. Yang, J. T. Belisle, J. R. Bleharski, M. Maitland, M. V. Norgard, S. E. Plevy, S. T. Smale, P. J. Brennan, B. R. Bloom, P. J. Godowski, and R. L. Modlin. 1999. Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipoproteins through toll-like receptors. Science 285**:**732-736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown, K., S. Park, T. Kanno, G. Franzoso, and U. Siebenlist. 1993. Mutual regulation of the transcriptional activator NF-κB and its inhibitor, IκB-α. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 90**:**2532-2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burkly, L., C. Hesslon, L. Ogata, C. Reilly, L. A. Marconi, D. Olson, R. Tizard, R. Cate, and D. Lo. 1995. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature 373**:**531-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burleigh, B. A., E. V. Caler, P. Webster, and N. W. Andrews. 1997. A cytosolic serine endopeptidase from Trypanosoma cruzi is required for the generation of Ca2+ signaling in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 136**:**609-620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Butcher, B. A., L. Kim, P. F. Johnson, and E. Y. Denkers. 2001. Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites inhibit proinflammatory cytokine induction in infected macrophages by preventing nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB. J. Immunol. 167**:**2193-2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caamaño, J., J. Alexander, L. Craig, R. Bravo, and C. A. Hunter. 1999. The NF-κB family member RelB is required for innate and adaptive immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 163**:**4453-4461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caamaño, J., C. Tato, G. Cai, E. Villegas, K. Speirs, L. Craig, J. Alexander, and C. A. Hunter. 2000. Identification of a role for NF-κB2 in the regulation of apoptosis and in maintenance of T cell-mediated immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. J. Immunol. 165**:**5720-5728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caamano, J. H., C. A. Rizzo, S. K. Durham, D. S. Barton, C. Raventos-Suarez, C. M. Snapper, and R. Bravo. 1998. NF-κB2 (p100/p52) is required for normal splenic microarchitecture and B cell mediated immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 187**:**185-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell, I. K., S. Gerondakis, K. O'Donnell, and I. P. Wicks. 2000. Distinct roles for the NF-κB1 (p50) and c-Rel transcription factors in inflammatory arthritis. J. Clin. Investig. 105**:**1799-1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos, M. A., I. C. Almeida, O. Takeuchi, S. Akira, E. P. Valente, D. O. Procopio, L. R. Travassos, J. A. Smith, D. T. Golenbock, and R. T. Gazzinelli. 2001. Activation of toll-like receptor-2 by glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors from a protozoan parasite. J. Immunol. 167**:**416-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cariappa, A., H. C. Liou, B. H. Horwitz, and S. Pillai. 2000. Nuclear factor κB is required for the development of marginal zone B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 192**:**1175-1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carrasco, D., J. Cheng, A. Lewin, G. Warr, H. Yang, C. Rizzo, F. Rosas, C. Snapper, and R. Bravo. 1998. Multiple hemopoietic defects and lymphoid hyperplasia in mice lacking the transcriptional activation domain of the c-Rel protein. J. Exp. Med. 187**:**973-984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carrasco, D., R. P. Ryseck, and R. Bravo. 1993. Expression of relB transcripts during lymphoid organ development: specific expression in dendritic antigen-presenting cells. Development 118**:**1221-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casolaro, V., S. N. Georas, Z. Song, I. D. Zubkoff, S. A. Abdulkadir, D. Thanos, and S. J. Ono. 1995. Inhibition of NF-AT-dependent transcription by NF-κB: implications for differential gene expression in T helper cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92**:**11623-11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan, V. W., I. Mecklenbrauker, I. Su, G. Texido, M. Leitges, R. Carsetti, C. A. Lowell, K. Rajewsky, K. Miyake, and A. Tarakhovsky. 1998. The molecular mechanism of B cell activation by toll-like receptor protein RP-105. J. Exp. Med. 188**:**93-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang, C. C., J. Zhang, L. Lombardi, A. Neri, and R. Dalla-Favera. 1995. Rearranged NFκB-2 genes in lymphoid neoplasms code for constitutively active nuclear transactivators. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15**:**5180-5187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng, J. D., R. P. Ryseck, R. M. Attar, D. Dambach, and R. Bravo. 1998. Functional redundancy of the nuclear factor κB inhibitors IκBα and IκBβ. J. Exp. Med. 188**:**1055-1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho, N. H., S. Y. Seong, M. S. Huh, T. H. Han, Y. S. Koh, M. S. Choi, and I. S. Kim. 2000. Expression of chemokine genes in murine macrophages infected with Orientia tsutsugamushi. Infect. Immun. 68**:**594-602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coyle, A. J., C. Lloyd, J. Tian, T. Nguyen, C. Erikkson, L. Wang, P. Ottoson, P. Persson, T. Delaney, S. Lehar, S. Lin, L. Poisson, C. Meisel, T. Kamradt, T. Bjerke, D. Levinson, and J. C. Gutierrez-Ramos. 1999. Crucial role of the interleukin 1 receptor family member T1/ST2 in T helper cell type 2-mediated lung mucosal immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 190**:**895-902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das, J., C. H. Chen, L. Yang, L. Cohn, P. Ray, and A. Ray. 2001. A critical role for NF-κB in Gata3 expression and TH2 differentiation in allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2**:**45-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Delhase, M., M. Hayakawa, Y. Chen, and M. Karin. 1999. Positive and negative regulation of IκB kinase activity through IKKβ subunit phosphorylation. Science 284**:**309-313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeLuca, C., L. Petropoulos, D. Zmeureanu, and J. Hiscott. 1999. Nuclear IκBβ maintains persistent NF-κB activation in HIV-1-infected myeloid cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274**:**13010-13016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doffinger, R., A. Smahi, C. Bessia, F. Geissmann, J. Feinberg, A. Durandy, C. Bodemer, S. Kenwrick, S. Dupuis-Girod, S. Blanche, P. Wood, S. H. Rabia, D. J. Headon, P. A. Overbeek, F. Le Deist, S. M. Holland, K. Belani, D. S. Kumararatne, A. Fischer, R. Shapiro, M. E. Conley, E. Reimund, H. Kalhoff, M. Abinun, A. Munnich, A. Israel, G. Courtois, and J. L. Casanova. 2001. X-linked anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency is caused by impaired NF-κB signaling. Nat. Genet. 27**:**277-285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doi, T. S., M. W. Marino, T. Takahashi, T. Yoshida, T. Sakakura, L. J. Old, and Y. Obata. 1999. Absence of tumor necrosis factor rescues RelA-deficient mice from embryonic lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96**:**2994-2999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doi, T. S., T. Takahashi, O. Taguchi, T. Azuma, and Y. Obata. 1997. NF-κB RelA-deficient lymphocytes: normal development of T cells and B cells, impaired production of IgA and IgG1 and reduced proliferative responses. J. Exp. Med. 185**:**953-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dong, G., E. Loukinova, Z. Chen, L. Gangi, T. I. Chanturita, E. T. Liu, and C. Van Waes. 2001. Molecular profiling of transformed and metastatic murine squamous carcinoma cells by differential display and cDNA microarray reveals altered expression of multiple genes related to growth, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and the NF-κB signal pathway. Cancer Res. 61**:**4797-4808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Donovan, C. E., D. A. Mark, H. Z. He, H. C. Liou, L. Kobzik, Y. Wang, G. T. De Sanctis, D. L. Perkins, and P. W. Finn. 1999. NF-κB/Rel transcription factors: c-Rel promotes airway hyperresponsiveness and allergic pulmonary inflammation. J. Immunol. 163**:**6827-6833. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dorado, B., P. Portoles, and S. Ballester. 1998. NF-κB in Th2 cells: delayed and long lasting induction through the TCR complex. Eur. J. Immunol. 28**:**2234-2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dudley, E., F. Hornung, L. Zheng, D. Scherer, D. Ballard, and M. Lenardo. 1999. NF-κB regulates Fas/APO-1/CD95- and TCR-mediated apoptosis of T lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 29**:**878-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duffey, D. C., Z. Chen, G. Dong, F. G. Ondrey, J. S. Wolf, K. Brown, U. Siebenlist, and C. Van Waes. 1999. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant inhibitor-κBα of nuclear factor-κB in human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma inhibits survival, proinflammatory cytokine expression, and tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Res. 59**:**3468-3474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reference deleted.

- 51.Ebnet, K., K. D. Brown, U. K. Siebenlist, M. M. Simon, and S. Shaw. 1997. Borrelia burgdorferi activates NF-κB and is a potent inducer of chemokine and adhesion molecule gene expression in endothelial cells and fibroblasts. J. Immunol. 158**:**3285-3292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elewaut, D., J. A. DiDonato, J. M. Kim, F. Truong, L. Eckmann, and M. F. Kagnoff. 1999. NF-κB is a central regulator of the intestinal epithelial cell innate immune response induced by infection with enteroinvasive bacteria. J. Immunol. 163**:**1457-1466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Esslinger, C. W., A. Wilson, B. Sordat, F. Beermann, and C. V. Jongeneel. 1997. Abnormal T lymphocyte development induced by targeted overexpression of IκBα. J. Immunol. 158**:**5075-5078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferreira, V., N. Sidenius, N. Tarantino, P. Hubert, L. Chatenoud, F. Blasi, and M. Korner. 1999. In vivo inhibition of NF-κB in T-lineage cells leads to a dramatic decrease in cell proliferation and cytokine production and to increased cell apoptosis in response to mitogenic stimuli, but not to abnormal thymopoiesis. J. Immunol. 162**:**6442-6450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feuillard, J., M. Korner, A. Israel, J. Vassy, and M. Raphael. 1996. Differential nuclear localization of p50, p52, and RelB proteins in human accessory cells of the immune response in situ. Eur. J. Immunol. 26**:**2547-2551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]