Using Linkage Genome Scans to Improve Power of Association in Genome Scans (original) (raw)

Abstract

Scanning the genome for association between markers and complex diseases typically requires testing hundreds of thousands of genetic polymorphisms. Testing such a large number of hypotheses exacerbates the trade-off between power to detect meaningful associations and the chance of making false discoveries. Even before the full genome is scanned, investigators often favor certain regions on the basis of the results of prior investigations, such as previous linkage scans. The remaining regions of the genome are investigated simultaneously because genotyping is relatively inexpensive compared with the cost of recruiting participants for a genetic study and because prior evidence is rarely sufficient to rule out these regions as harboring genes with variation of conferring liability (liability genes). However, the multiple testing inherent in broad genomic searches diminishes power to detect association, even for genes falling in regions of the genome favored a priori. Multiple testing problems of this nature are well suited for application of the false-discovery rate (FDR) principle, which can improve power. To enhance power further, a new FDR approach is proposed that involves weighting the hypotheses on the basis of prior data. We present a method for using linkage data to weight the association P values. Our investigations reveal that if the linkage study is informative, the procedure improves power considerably. Remarkably, the loss in power is small, even when the linkage study is uninformative. For a class of genetic models, we calculate the sample size required to obtain useful prior information from a linkage study. This inquiry reveals that, among genetic models that are seemingly equal in genetic information, some are much more promising than others for this mode of analysis.

Methods to detect liability alleles for complex disease are at a crossroads. Previously, tests of association between disease status and alleles at specific markers targeted several markers within a handful of candidate genes. With the advent of relatively inexpensive molecular methods for genotyping, the trend is moving toward whole-genome association studies (Thomas et al. 2005). Such investigations might involve hundreds of thousands of markers and hypothesis tests. Current analytical tools for such massive investigations are limited. The ultimate success of whole-genome association studies will depend largely on the development of innovative analytic strategies.

Although the whole genome might be tested for association with the disorder of interest, typically, some regions of the genome are favored because of prior investigations or knowledge of the biological function of particular genes. Other regions are investigated simultaneously because genotyping is relatively inexpensive compared with the cost of recruiting study participants and the cost of designing large-scale study-specific assays. Moreover, for complex phenotypes, few regions can be excluded as not harboring liability genes.

For any well-calibrated statistical procedure, simultaneously looking for association across the whole genome leads to a loss in power to detect signals in a specified list of genes. Some statistical approaches, however, are better suited to large-scale testing than others. For instance, if we aim to control the false-discovery rate (FDR), defined as “the expected fraction of false rejections,” the loss in power will be less than if we aim to control the type I error rate (Genovese and Wasserman 2002; Benjamini and Hochberg 1995). For this reason, FDR procedures are widely used in multiple-testing problems that arise in genetic studies (Efron and Tibshirani 2002; Devlin et al. 2003_a_, 2003_b_; Sabatti et al. 2003; Storey and Tibshirani 2003).

To enhance the power to detect association in favored regions while simultaneously testing the whole genome, we considered an FDR procedure that facilitates weighting hypotheses on the basis of prior information (Genovese et al. [in press]; see also Benjamini and Hochberg [1997]). Specifically, our goal was to increase the power to detect signals for association in preselected regions by judiciously “up-weighting” the relevant P values while “down-weighting” P values in all other regions. Linkage data offer a natural choice for weighting the P values for a whole-genome association study. In the present study, we investigated how linkage traces can be formulated as weights. If some of the loci under linkage peaks are indeed more likely to be associated with the phenotype than the others, then the weighted procedure offers a chance to maintain good power even in a whole-genome association study. Remarkably, we will show that if the linkage trace is informative, then power is enhanced; yet, with uninformative linkage traces, the procedure experiences a fairly small loss in power. We also provide guidance on the type of genetic models and required sample sizes likely to yield informative weights. Although we focused our investigation on weighted FDR procedures, these ideas can be easily applied to other multiple-testing procedures, such as Bonferroni and Holm’s procedure (Holm 1979).

Methods

The proposed multiple-testing situation consists of m hypotheses _H_1,…,H m, for which H _i_=1 if the i_th null hypothesis is false, and 0 otherwise. The evidence corresponding to the i_th test for association is summarized in the P value P i. The ordered P values are indicated as P(1)⩽_P(2)⩽⋅⋅⋅_P(n), with P(0) defined to be 0 for convenience.

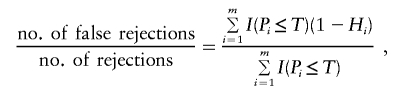

Many FDR-based procedures are based on the following pattern: reject each hypothesis for which P i is less than or equal to a threshold T that is selected on the basis of the observed P values so as to maintain FDR at level α. The FDR at threshold T is defined to be the expectation of

where the ratio is defined to be 0 when the denominator is 0. The most common procedure for choosing T is that of Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) and is given by

Let _w_1,…,w m be the chosen weights. Following the argument for the Benjamini and Hochberg (1995) FDR procedure, the “wBH” procedure of Genovese et al. (in press) finds the threshold for rejection (T) that controls the FDR at rate α when the weighted values {P i/w i} play the role of the P values. In practice, the weights adjust the threshold for rejection individually for each P value, in that we reject the _i_th hypothesis if P i_⩽_w i T.

To illustrate the effect of weights, we present a theoretical exploration of the power of weighted tests that would have had 50% power in the absence of weighting. Tests with considerably more power will not benefit substantially from weighting, and tests with less power are not likely to be powerful even with weights. We call these 50%-power alternatives “marginal” because they are on the margin of detectability. In this context, power is defined as the probability that P i/w i_⩽_T.

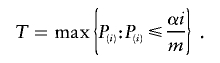

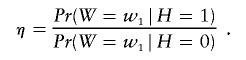

To maintain FDR at a fixed level, a set of prior weights {w i} must satisfy two criteria: w _i_⩾0 and

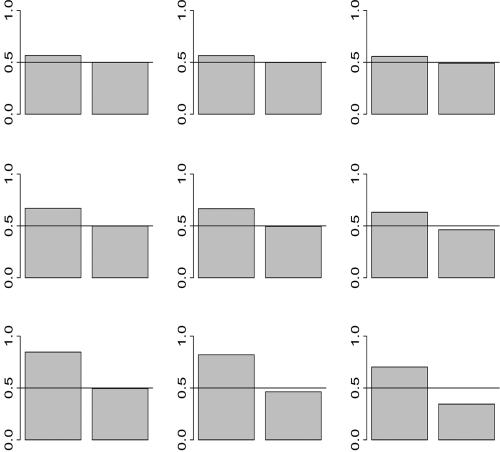

(Genovese et al., in press). Thus, candidates for linkage-based weights are numerous. For simplicity of exposition, we initially consider binary weights with a fraction ε of weights w_1≡_B/(_B_ε+1-ε)—that is, up-weighted—and the remainder _w_0≡1/(_B_ε+1-ε) down-weighted. In figure 1, we compare the achieved power over a grid of choices for the two free parameters, ε=(0.001,0.01,0.1) and _B_=(2,6,50). Within each bar plot, the left (right) bar reveals the power if the value is up-weighted (down-weighted). Thus, the bars show the deviation from the marginal unweighted power (0.5) and the contrast in power if a test is correctly up-weighted or incorrectly down-weighted. For a given ε, the power gain for the up-weighted tests increases as B increases. Meanwhile, the down-weighted tests lose increasingly more power as B increases; however, the loss is disproportionately smaller than the gain attained by the up-weighted tests. The potential gains are more striking if ε is small, whereas the potential losses are greater if ε is large. In effect, as ε increases, constraining the average weight to be 1 results in more-modest up-weights and more-severe down-weights. This reduces the power to detect a given signal, regardless of whether it is up- or down-weighted. This analysis reveals that sparse, dramatic weights can yield large increases in power with very little potential loss. There is a catch, though. This striking improvement in power is attainable only if the weights are correctly placed. With small ε, it is much more challenging to place the weights correctly. A causal variant is more likely to be up-weighted if ε is larger.

Figure 1.

Achieved power of a single test for a variety of binary weighting schemes. Within each bar plot, the left (right) bar reveals the power if the value is up-weighted (down-weighted). The plot displays the deviation in power of the weighted test from the marginal unweighted power (0.5). Rows, from top to bottom, are _B_=2, 6, and 50; columns. from left to right, are ε=0.001, 0.01, and 0.1.

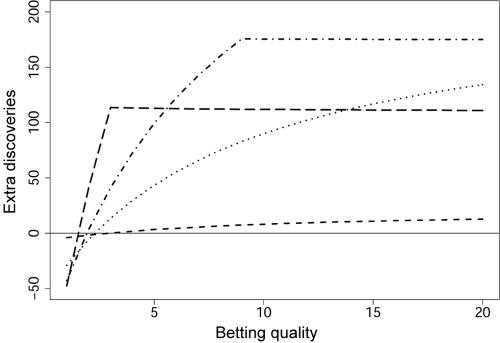

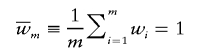

Next, we considered the effect of weights on the number of discoveries made. Consider a situation in which _H_=1 for a fraction 0<a<1 of the tests, and use the binary weights described above. It is convenient for this analysis to treat the weights as random variables. A measure of the informativeness of the betting is

When η=1, W and H are independent; for η>1, there is greater likelihood of betting correctly, and, for 0⩽η<1, incorrectly. With use of marginal alternatives, half of the tests with H_=1 are likely to be discovered. We measure our genomewide success rate by counting how many true discoveries are made in excess of expectation. Figure 2 considers a scenario in which _m_=10,000, _a_=0.1, and η varies between 0 and 20. We consider four choices of ε(0.01,0.1,0.2,0.4). (For ε>a, η is a bounded quantity). When ε<_a_, the gain in discoveries is modest regardless of η (short-dashed line). When ε=_a_, the number of excess discoveries increases smoothly with η (dotted line). For η close to 1, a choice of ε>a leads to more discoveries than obtained when η=a; however, this advantage is lost as η increases (dot-dashed line =0.2; long-dashed line =0.4). From this analysis, we conclude that an optimal choice of ε is slightly ⩾_a.

Figure 2.

Extra discoveries as a function of the quality of the bets. The scenario investigated has m_=10,000 tests, and a fraction (a_=0.1) of them are nonnull. The quality of the bets, measured in terms of η, varies between 0 and 20. We consider four choices of ε: 0.01 (short-dashed line), 0.1 (dotted line), 0.2 (dot-dashed line), and 0.4 (long-dashed line).

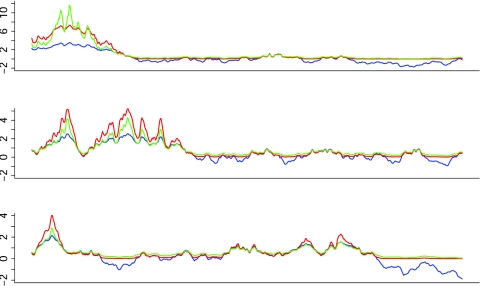

For our application, the value of the linkage test at the position of the _i_th association test z i is the basis for the proposed weighting system. For linkage data, the test statistics along a chromosome can be summarized as a Gaussian process that, at any point on the chromosome, is approximately normally distributed. Under the null hypothesis, the distribution has mean 0 and variance 1. Unlike the binary scenario investigated thus far, the test statistics are strongly correlated within a chromosome. Even under the alternative hypothesis, a linkage peak for a complex disease tends to be broad and ill defined (fig. 3; blue) because of the physical process of recombination. It is desirable to up-weight the entire region under a linkage peak to capture the causal variant (or variants). Because linkage results are quantitative, and because a linkage peak is not a well-defined region, we consider continuous weights.

Figure 3.

Plot of linkage traces for three chromosomes with weights. The green and red traces are weights with exponential (_B_=1) and cumulative (_B_=2) weights, respectively, that are based on the linkage trace (blue). The bottom panel has no signal.

We use the following heuristic to motivate our exponential weighting scheme. Assume the model-free linkage statistics are distributed normally (β,1), with mean β=0 when unlinked and β>0 when linked. A natural weighting candidate is the posterior odds that an observation is linked, which is proportional to v _i_=e_β_z i. Because the weights are constrained to have mean 1,  is a valid choice. Thus, choosing the weights is tantamount to choosing a constant _B_⩾0 to play the role of the unknown quantity β.

is a valid choice. Thus, choosing the weights is tantamount to choosing a constant _B_⩾0 to play the role of the unknown quantity β.

The exponential weighting scheme with _B_=1 is depicted in figure 3 (green). The implicit meaning of ε in the binary weighting scheme is determined automatically by the number and length of the linkage peaks. If there are many peaks, then the up-weighting will be constrained more strongly by the requirement that  . Increasing B decreases the length of the peak that is strongly up-weighted. Consequently, whereas a large value of B will yield greater power in some instances, it might fail to up-weight a causal variant located away from the crest of the corresponding linkage peak.

. Increasing B decreases the length of the peak that is strongly up-weighted. Consequently, whereas a large value of B will yield greater power in some instances, it might fail to up-weight a causal variant located away from the crest of the corresponding linkage peak.

Exponential weights have the disadvantage of being highly sensitive to large values, a feature that is particularly apparent in the top panel of figure 3. For this reason we considered cumulative weights, defined as φ(_z_-B), where φ(·) is the standard normal cumulative distribution function. This function has the desirable property of increasing approximately linearly for values of z near B, but quickly reaching an asymptote for large values of |_z_-B|. Consequently, it gives approximately equal up-weighting (down-weighting) to any z value 2 or more units above (below) B. See figure 3 (red) for a comparison between the exponential and cumulative weights; _B_=1 for the former and _B_=2 for the latter. Cumulative weighting has the advantage of providing smoother up-weights and broader peaks. Its disadvantage is that it strongly down-weights regions without linkage signals, perhaps making it an inferior choice when the linkage input is uninformative because of low power. This feature is most apparent in the bottom panel of figure 3.

Results

Simulations

To evaluate wBH, we simulate whole-genome linkage traces (22 autosomes and chromosome X) and corresponding association tests. We simulate linkage traces that approximate the information obtainable from an independent 10,000-SNP linkage study. Because of practical constraints on computation time, we simulate the linkage traces indirectly. As described by Bacanu (2005), we approximate linkage traces on chromosomes as independent realizations of an underlying time series process. The linkage trace is constructed by adding random noise to a deterministic model of the linkage signal. The random noise of a linkage trace is distributed as a Gaussian process from an autoregressive moving average (ARMA 2,1) model with parameters _ar_1=1.51, ar_2=-0.51, and ma_1=0.22 (Venables and Ripley 2002). This model was selected on the basis of features expected in actual linkage traces (see appendix A for details). To introduce L linkage signals, the position of the disease variant is randomly placed on L chromosomes, one signal per chromosome. Each expected signal is centered at the designated location, with peak height μ_l , which decays smoothly to zero as the distance t from the disease variant increases. If the autocorrelation pattern determined by the ARMA model is ρ(t), then a marker t units from the disease variant has signal equal to ρ(t)μ_l. Chromosomes with no disease variants have signal equal to zero at all points. The resulting traces resemble the outcome of a linkage study that relies on sib pairs, analyzed using a model-free linkage analysis, for a complex genetic disease.

Superimposed on the linkage traces are m_=500,000 (250,000) simulated association statistics, equally spaced in genetic distance. To realistically simulate a dense set of association data, detailed information about the linkage disequilibrium (LD) structure between SNPs would be required. Such a detailed simulation, however, would be impractical for this investigation. Consequently, we simulated independent association tests. The P values for the noncausal association statistics are uniformly distributed. Each of the P values obtained from one of the L disease variants is derived from a normal N(μ_a,1) test statistic.

Our simulations explore various levels of signals that might be encountered in practice under a wide variety of genetic models. The intensity of the signal is a statistical parameter, not immediately interpretable via the genetic model. The quantities μ_l_ and μ_a_ represent the shift in the mean of the linkage and association test statistics, respectively, between the unlinked and linked hypotheses. The shift is determined by the informativeness of the genetic model for the designated type of study and the size of the sample. Theoretically, any desired combination of linkage and association shifts could be attained with appropriate sample sizes in each type of study. However, for some genetic models, the sample size required might be immense for a linkage and/or association study. Below, we discuss further the connection between the statistical parameters and the genetic models.

For each of >50 simulation conditions, which correspond to specific levels of μ_l_ and μ_a_ , we generated 100 linkage traces and 10 replicate association studies per linkage trace. Consequently, at each level, the performance of the inference procedures were estimated from 1,000 simulations. In addition, of _m_=500,000 association tests, _L_=10 disease variants were present. We also tried _L_=5 and 15 of _m_=250,000 and 500,000 tests, but the results for those conditions were qualitatively similar to those for _L_=10 and _m_=500,000, so those results are not shown.

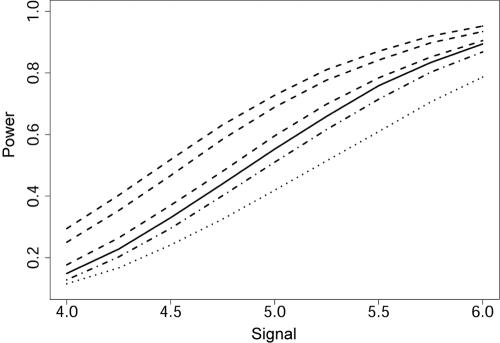

Simulations displayed in figure 4 show that solid gains in power are possible with wBH (dashed lines) as compared with BH (solid line) and especially compared with the traditional Bonferroni correction for multiple testing (dotted line). For signals arising from weak, moderate, and strong linkage signals (μ_l_=1.0, 2.5 and 3.5—dashed lines, from lowest to highest, respectively), the increase in power is steady across the range of association signals (μ_a_=4.0–6.0). The increase when μ_l_=1 is encouraging. With such a weak signal, the linkage trace is likely to appear to have no meaningful signals. It is also noteworthy that moving from good (μ_l_=2.5) to excellent (μ_l_=3.5) information does not result in a dramatic improvement in power. There appears to be a limit to how much power can be obtained from linkage-based weights.

Figure 4.

Power as a function of μ_a_ . Power is defined as the number of true discoveries of _L_=10 causal variants. Distinct lines correspond to different methods and/or linkage signals, coded as follows (from lowest to highest power): dotted is the Bonferroni method; dot-dashed is wBH through use of linkage data with no signal (μ_l_=0); solid is the BH method (Storey’s 2002 version); dashed are wBH through use of linkage data with a weak (μ_l_=1), moderate (μ_l_=2.5), and strong (μ_l_=3.5) signal.

The linkage shift of μ_l_=0 is intended to approximate a linkage study that has essentially no power because of insufficient sample size. As noted by Risch and Merikangas (1996), this scenario is certainly plausible. The simulations reveal that a fairly small amount of power is lost because of weights that are based on an uninformative linkage study (μ_l_=0) (fig. 4; dot-dashed line). Even with uninformative weights, the power of wBH is greater than that obtained using a Bonferroni correction. In the best-case scenario, increases in power over Bonferroni-corrected tests can be >35%. The wBH results were obtained using exponential weights with _B_=1. Very similar results were obtained when cumulative weights with _B_=2 were used. Exponential weights slightly outperformed cumulative weights when μ_l_=0.

We also investigated other choices of constants for the weighting schemes. In practice, we found that good choices for the arbitrary parameters are _B_=1 for exponential weighting and _B_=2 for cumulative weighting, because they provide a substantial gain in power when the linkage trace is informative and a small loss in power when the linkage trace is uninformative.

Another interesting feature of the simulations is the behavior of the linkage signals for individual genome scans. Although there were _L_=10 loci that could produce linkage signals, for any particular simulation, only a few of those loci were likely to produce a notable linkage signal, even when μ_l_=3.5. In fact, for a commonly accepted bound for significant linkage—a LOD of 3.6 (Lander and Kruglyak 1995) and μ_l_=1.0, 2.5, and 3.5—the expected numbers of loci exceeding the threshold are 0.01, 0.6, and 2.8 of 10; for suggestive linkage—requirement of a LOD of 2.2 and μ_l_=1.0, 2.5, and 3.5—the expected numbers of loci exceeding the threshold are 0.1, 2.5, and 6.2 of 10. Naturally, when μ_l_=0.0, the expected number of loci exceeding either bound is essentially 0 of 10.

The size of the weights varies as a function of many factors, including characteristics of the linkage trace (the number, width, and height of the peaks), the choice of weight function, and related parameter B. To provide insight into to the size of weights in our simulations, we summarized the mean and variance of the weights derived from the various types of linkage traces evaluated at the 10 causal variants (table 1). When there was no notable signal in the linkage data, the weights were approximately equal to unity, on average, which is a desirable feature. As the linkage signal increased, so did the weights (table 1). The increase was more dramatic for exponential weights than for cumulative weights. Notably, the exponential weights were more variable than the cumulative weights, which suggests the cumulative weights could be a better choice.

Table 1.

Distribution of Weights at the Causal Variants

| Exponential | Cumulative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μl | Mean | Variance | Mean | Variance |

| 0 | 1.01 | 1.73 | 1.00 | 2.68 |

| 1 | 2.28 | 7.65 | 2.48 | 5.99 |

| 2.5 | 6.69 | 64.1 | 4.71 | 4.22 |

| 3.5 | 11.8 | 179 | 5.07 | 1.35 |

Relating Genetic Models to Statistical Models

The intensity of the signals from linkage and association studies are determined by the underlying genetic model and the sample size. With some statistical manipulation, the expected signal resulting from the genetic model can be parameterized by the statistical shift parameters μ_l_ and μ_a_ used in our simulations. In this section, we develop a mapping between the statistical parameters and the genetic models. This mapping should be useful for evaluating the results of our simulations and for the design of whole-genome association studies, especially realistic evaluation of their power.

For a given sample size and genetic model, we can compute the resulting shift of the linkage and/or association test statistic by making use of two statistical relationships. For simplicity of exposition, we assume that an observation in a linkage study is a fully informative affected sib pair (ASP). In an association study, an observation is a single case and a single control. For a particular genetic model and study design, a certain amount of information is expected per observation, and the sum of this information over observations is called the “noncentrality parameter.” This quantity determines the shift parameter. Next, a regression model can summarize the functional relationship between a genetic model and the sample size required to achieve a particular size of shift for a particular study design.

We investigate a variety of genetic models that assume a prevalence of κ (0.01–0.03), a disease variant that occurs in the population with frequency ρ (0.05–0.5), and an additive penetrance model. Models vary in the levels of genetic effect assumed. To obtain small-to-moderate genetic effects, we consider models with an odds ratio (φ) of 1.5–3.0. This quantity indexes the genetic effect of the disease variant independent of the prevalence κ; however, as with all measures of genetic impact, the strength of a given value can be interpreted only within the context of the other parameters in the genetic model. Some measures of genetic effect are more useful for linkage analysis, whereas others are more useful for association analysis. For this reason, we also report the risk to relatives (λ) (Risch 1990) and the attributable fraction (Δ) (Pfeiffer and Gail 2003). The latter, which is equivalent to Levin’s population-attributable risk, is defined to be one minus the ratio of the probability of affection, given that an individual has no copies of the detrimental allele, over the prevalence.

To see how the apparent genetic effect varies with the measure, consider two models, each with κ=0.01 and φ=2. If the causal variant is uncommon (ρ=.05), Δ=9% and λ=1.04, whereas, if the causal variant is common (ρ=.5), the apparent genetic effect is much stronger: Δ=66% and λ=1.11. From Δ and λ, we see that, when ρ is small, it will be difficult to detect the signal if φ⩽2, because most of the risk will not be attributable to the locus.

The number of ASPs (n l) necessary to achieve a signal of size μ_l_=2.0 in a linkage analysis with fully informative markers is given for a variety of genetic models (table 2). For each model, the corresponding number of cases (n a) necessary to achieve a signal of size μ_a_=4.5 in a case-control association study with equal numbers of cases and controls is given, with the assumption that the disease variant is measured. Notice that some genetic models are favorable to association studies, whereas others are favorable to linkage studies. For instance, when κ=0.01, φ=2, and ρ=0.05, the required sample size for a linkage study is large (n _l_=5,664), yet, for an association study, it is tenfold smaller (n _a_=648).

Table 2.

Linkage and Association Sample Sizes Required to Obtain Shifts of μ_l_=2.0 and μ_l_=4.5, Respectively, for Various Genetic Models

| Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | κ | φ | Δ | λ | n l | n a |

| .05 | .01 | 1.5 | .05 | 1.01 | 67,219 | 2,278 |

| .05 | .01 | 2 | .09 | 1.04 | 5,664 | 641 |

| .05 | .01 | 3 | .18 | 1.15 | 544 | 225 |

| .05 | .2 | 1.5 | .04 | 1.01 | 207,635 | 2,448 |

| .05 | .2 | 2 | .07 | 1.03 | 21,596 | 750 |

| .05 | .2 | 3 | .11 | 1.07 | 2,617 | 304 |

| .2 | .01 | 1.5 | .18 | 1.03 | 8,067 | 659 |

| .2 | .01 | 2 | .33 | 1.11 | 612 | 167 |

| .2 | .01 | 3 | .56 | 1.32 | 97 | 63 |

| .2 | .2 | 1.5 | .14 | 1.02 | 22,385 | 700 |

| .2 | .2 | 2 | .25 | 1.08 | 2,096 | 193 |

| .2 | .2 | 3 | .41 | 1.21 | 418 | 84 |

| .5 | .01 | 1.5 | .4 | 1.04 | 5,046 | 491 |

| .5 | .01 | 2 | .66 | 1.11 | 474 | 150 |

| .5 | .01 | 3 | .99 | 1.25 | 145 | 67 |

| .5 | .2 | 1.5 | .32 | 1.03 | 12,486 | 509 |

| .5 | .2 | 2 | .54 | 1.09 | 1,447 | 169 |

| .5 | .2 | 3 | .83 | 1.22 | 559 | 87 |

Table 2 shows the range of the genetic model space we explored, but only a fraction of the specific settings. To obtain estimates of the sample sizes required for linkage and association studies for other genetic models, we provide a regression model that is a function of (ρ,κ,φ). See appendix B for details. For both regression models, the fit was excellent (_R_2>99%).

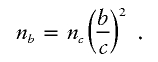

For a given genetic model defined by (ρ,κ,φ), let N l and N a denote the sample size required to obtain shift parameters of μ_l_=2.0 and μ_a_=4.5, respectively. We chose these shift parameters for illustrative purposes only. It is straightforward to extend to other desired shift parameters. If n c is the sample size necessary to obtain a linkage shift of size c, then to obtain a shift of size b, we require a sample size of

From the regression model and for _c_=2.0, n c is well approximated by N l . Substituting this in the formula yields the desired sample-size estimate for the given genetic model.

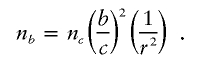

For an association study, it is quite likely that the causal SNP is unmeasured. Let _r_2 denote the Pearson squared correlation between the allele count at the causal SNP and the most highly correlated SNP that is measured. As in the linkage scenario, it follows that if n c is the sample size necessary to obtain an association shift of size c when the causal SNP is measured, then to obtain a shift of size b with an unmeasured causal SNP, we require a sample size of

These formulas may be used in reverse as well. Suppose sample sizes are predetermined. Then, for a plausible genetic model, one can compute the expected shift, b, in the formula above. See appendix B for detailed numerical examples of these calculations.

Discussion

When planning a whole-genome study to discover genes associated with a complex phenotype, a host of issues arise, many of which were discussed in a recent review by Thomas et al. (2005). To detect association via LD in a typical population requires a marker density on the order of 1 every 6 kb, which results in ∼500,000 SNP markers. Many investigators have recommended a two-stage association analysis to circumvent the challenges of multiple testing (e.g., Sobell et al. [1993] and Satagopan and Elston [2003]). The concept of this study design is to perform an analysis on an initial sample of subjects for a dense grid of markers and then to follow up with an independent sample, tested for only the markers yielding “promising” results in the first stage. Although this approach is helpful, testing such a large number of hypotheses makes it difficult to detect meaningful associations. In the present study, we propose a novel approach for improving the power of a whole-genome association study that is applicable to one- or two-stage designs.

Investigators typically favor certain regions of the genome on the basis of the results of prior investigations, such as linkage analysis. We propose using this information in the form of weights for the P values. Specifically, we divide P values by weights and then apply the traditional FDR procedure to the weighted P values. We investigate how weights might sensibly be chosen on the basis of a prior linkage study. Our investigations reveal that if the prior weights are informative, the procedure improves power considerably. Remarkably, even if the weights were uninformative, the loss in power is small.

Theory imposes few constraints on the weights beyond a basic conservation principle: the weights must average to 1. There remain many open questions about how to best incorporate information from multiple prior linkage studies. Presumably, the basic principles of meta-analyses can be applied to combine information into a single, so-called meta-linkage trace. Another obvious candidate for weights is “gene-based” and involves up-weighting regions—including coding, splice-site, and regulatory regions—and conserved intronic regions (see Thomas et al. 2005). Nevertheless, although many different weighting schemes are permissible in principle, searching to find the weights that give the desired significant results is not acceptable. For this reason, we give some suggested weighting schemes and presume that any other choice of weights would require scientific motivation before it would be considered valid.

From simulations, it is clear that a few dramatic weights are ideal if the prior data are highly informative. Otherwise, modest weights provide a more robust choice. For linkage-based weights, such as the exponential weights, it might be ideal to have a way of choosing the constant B to maximize the power of the analysis. A data-driven option to achieve this goal is to select the B that maximizes the number of discoveries for a particular genome scan; call it D(B). Simulations reveal that D(B) is a well-behaved step function. In most simulations, it starts low, steps up quickly to a maximum value, stabilizes for a broad range of choices, and then declines as B gets larger. The exception is when the linkage trace is uninformative. In this case, the B that maximizes D(B) typically occurs for a value near zero. Although this empirical approach is appealing, it does have one notable drawback. Because the rate of false discoveries is controlled in expectation at level α for each B, maximizing the number of discoveries over B leads to an excess of false discoveries. Our simulations suggest, however, that this approach results in a minor increase in FDR of ∼0.04 over α=0.05. This increased error rate was often accompanied by a more-than-compensatory increase in power (results not shown). This promising idea requires further study. Already, it can provide a useful tool for selecting genes meriting further investigation.

In consideration of the use of prior information to improve testing, a Bayesian approach comes to mind. Indeed, the Bayesian FDR method given by Genovese and Wasserman (2003) can easily be extended to incorporate distinct priors for each hypothesis. Storey (2002) and Efron et al. (2001) have given Bayesian interpretations of FDR. Here, we have proposed using P value weighting as a frequentist method for including prior information about the hypothesis, while leaving the false discovery rate unchanged. The relationship between weighted FDR and a fully Bayesian procedure for evaluating linkage and association is not obvious to us but could be an interesting area of inquiry.

Risch and Merikangas (1996) compared the power of case-control association designs to linkage studies that used ASPs. For realistic sample sizes, they showed that some genetic models were much more likely to produce substantial association statistics than they were to produce substantial linkage statistics. We revisited this topic and calculated the sample size required to obtain useful prior information from a linkage study for the space of genetic models likely to underlie complex phenotypes (table 2). This inquiry reveals that, among genetic models that are seemingly equal in genetic information, as measured in terms of roughly equal sample sizes required to detect an association signal, some are much more informative for linkage than others. This observation reinforces the fact that loci “detectable” by linkage designs are not always the same as those detectable by association, and vice versa. Nonetheless, by exploring the power of the weighted procedures for a wide range of scenarios, we show that weighted FDR can improve power for scenarios quite likely to be relevant for some complex diseases/phenotypes. A caveat is also worth noting: our simulations assume the loci important for generating liability in multiplex families and those generating liability in population-based samples overlap. It is theoretically possible that there is little overlap for these two sets of loci; in that case, using linkage information to weight association statistics will not improve power as substantially as our results suggest.

Even when a dense set of markers has been genotyped, the choice of tag SNPs is critical to ensure that signals are detectable indirectly via LD (Rinaldo et al. 2005). The best tag SNPs to pick depends somewhat on the nature of the statistical analysis planned (Roeder et al. 2005). In our simulations, we ignored the LD structure in the genome and assumed that the association test statistics were independent. In practice, tests will be correlated, but, for well-selected tag SNPs, the correlation will be modest. Fortunately, for the type of correlation anticipated, FDR procedures maintain their validity (Devlin et al. 2003_a_; Storey et al. 2004).

For ease of exposition, we assumed that the P values were derived from normally distributed association tests. Because of a well-known relationship between the square of a normal statistic and the χ2 test, the conclusions we draw are directly applicable to 1-df χ2 test of association between SNP and phenotype. Moreover, because the FDR methods are P value based, any tests, including those based on haplotypes, are directly applicable to our weighted procedures. Using P values has the advantage of placing all tests, no matter the degree of freedom, on a common scale.

In closing, we note that technology has a tremendous effect on scientific inquiry, not all of it positive. In the workshop on genomewide association scans, Alice Whittemore asked “Is the technology driving the science?” (Thomas et al. 2005, p. 342). In the case of genomewide association studies, it is important to recall that just because we can afford to measure hundreds of thousands of SNPs does not mean we should let this additional data diminish our chances of detecting association signals in a targeted set of genes. The methods we propose allow scientific intuition to coexist more comfortably with emerging technology. Yes, we can measure more, but we can also use our scientific prior insights to target promising regions through the use of weights.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health grant MH057881. Free software for performaing weighted FDR analysis can be obtained at the Web site of the Computational Genetics Lab (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center).

Appendix A

A linkage scan with 10,000 SNPs takes considerable computer time to simulate; on a 1.4-GHz Opteron processor, simulation of a single linkage scan required 25 min. To estimate power, thousands of simulations are needed for each experimental condition investigated. Thus, direct simulation and analysis of 10,000 SNP linkage scans are infeasible, even on a cluster of processors.

In our simulations, we required an accurate approximation of the underlying time-series process. Consequently, we researched the appropriateness of an ARMA process to model the autocorrelation structure of linkage traces for 10,000 scans. For this purpose, we simulated and analyzed two data sets under the null hypothesis of no linkage between disease and markers. The two data sets comprised 400 ASPs. Each family has genotyped parents and missing genotypes at 7% of the loci overall. The data sets were simulated using SIMULATE (Terwilliger et al. 1993), and the linkage statistics were output every 1/3 cM, by use of Allegro (Gudbjartsson et al. 2000), with an exponential model option. We used the ARMA function in the R software (Venables and Ripley 2002) to fit two data sets to each of 16 models in the family of ARMA models, with AR and MA orders between 0 and 3. By using Akaike’s information criterion (AIC), the best fits were obtained using ARMA(2,1) and ARMA(3,1) models. Time-series diagnoses showed that these models provided a good fit to the autocorrelation function for statistics from map locations separated by <50–60 cM. Whereas the fit was not as good for statistics separated by >60 cM, both the empirical and fitted autocorrelations were close to zero at that distance and thus had little practical impact.

Appendix B

After computing n l (n a) for a broad range of values of κ,ρ,φ, we fit a generalized linear model with the log link to predict n l (n a) from κ,ρ,φ, the square root of each of these terms, and all pairwise interactions. The best models among this class were chosen using the stepwise AIC option. The resulting models, which had _R_2=99.9% for linkage and 99.4% for association, are presented in table B1. These are the models to obtain μ_l_=2 (μ_a_=4.5) for a linkage (association) study.

Table B1.

Coefficients for Log Linear Models to PredictRequired Sample Size to Obtain a Given Signal for Linkage and Association[Note]

For instance, if the genetic model is specified by ρ=0.25, κ=0.05, and φ=3, we can use table B1 to compute the number of sib pairs necessary to obtain an expected shift of μ_l_=2 in a linkage study. Simply calculate n l_=exp{x_′γ_l}, where x is the vector (1,κ,ρ,φ,…, and γ_l is the vector of linkage coefficients from table B1. Performing this calculation for the designated model, we find that ∼125 sib pairs will be required. The numbers reported in table 2 were obtained for a subset of genetic models with use of this formula, but with greater numerical precision in the coefficients. We can also compute the number of sib pairs necessary to obtain a shift of size _b_≠2 with use of the adjustment formula presented in the “Results” section. For example, if _b_=3, we calculate

and γ_l is the vector of linkage coefficients from table B1. Performing this calculation for the designated model, we find that ∼125 sib pairs will be required. The numbers reported in table 2 were obtained for a subset of genetic models with use of this formula, but with greater numerical precision in the coefficients. We can also compute the number of sib pairs necessary to obtain a shift of size _b_≠2 with use of the adjustment formula presented in the “Results” section. For example, if _b_=3, we calculate  .

.

To determine the sample size necessary to obtain a shift of size μ_a_=4.5 in an association study, we calculate n a_=exp{x_′γ_a}, where γ_a is the vector of association coefficients from table B1. For this example, if the causal SNP is measured, then ∼62 cases and controls will be required to obtain the desired results. On the other hand, if the causal SNP had not been measured but has maximum correlation _r_=0.8 with a measured SNP, then an additional 35 cases and controls would be required to obtain the same expected shift. Finally, if we have 200 cases and controls available, we expect a shift of  . As indicated in table 2, these values are highly dependent on the assumed genetic model.

. As indicated in table 2, these values are highly dependent on the assumed genetic model.

Web Resource

The URL for software presented herein is as follows:

- University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, http://wpicr.wpic.pitt.edu/wpiccompgen/

References

- Bacanu S-A (2005) Robust estimation of critical values for genome scans to detect linkage. Genet Epidemiol 28:24–32 10.1002/gepi.20030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57:289–300 [Google Scholar]

- ——— (1997) Multiple hypothesis testing with weights. Scand J Stat 24:407–418 10.1111/1467-9469.00072 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin B, Roeder K, Wasserman L (2003_a_) Analysis of multilocus models of association. Genet Epidemiol 25:36–47 10.1002/gepi.10237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ——— (2003_b_) False discovery or missed discovery? Heredity 91:537–538 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Storey J, Tusher VG, Tibshirani R (2001) Empirical Bayes analysis of a microarray experiment. J Am Stat Assoc 96:1151–1160 10.1198/016214501753382129 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani R (2002) Empirical Bayes methods and false discovery rates for microarrays. Genet Epidemiol 23:70–86 10.1002/gepi.1124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Roeder K, Wasserman L. False discovery control with p-value weighting. Biometrika (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Genovese CR, Wasserman L (2002) Operating characteristics and extensions of the false discovery rate procedure. J R Stat Soc B 64:499–518 10.1111/1467-9868.00347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ——— (2003) Bayesian and frequentist multiple testing. In: Bernard JM, Bayarri MJ, Berger JO, Dawid AP, Heckerman D, Smith AFM, West M (eds) Bayesian Statistics. Vol 7. Oxford University Press, Oxford, United Kingdom, pp 145–161 [Google Scholar]

- Gudbjartsson DF, Jonasson K, Frigge ML, Kong A (2000) Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analysis. Nat Genet 25:12–13 10.1038/75514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm S (1979) A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat 6:65–70 [Google Scholar]

- Lander E, Kruglyak L (1995) Genetic dissection of complex traits: guidelines for interpreting and reporting linkage results. Nat Genet 11:241–247 10.1038/ng1195-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeiffer RM, Gail MH (2003) Sample size calculations for population- and family-based case-control association studies on marker genotypes. Genet Epidemiol 25:136–148 10.1002/gepi.10245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldo A, Bacanu SA, Devlin B, Sonpar V, Wasserman L, Roeder K (2005) Characterization of multilocus linkage disequilibrium. Genet Epidemiol 28:193–206 10.1002/gepi.20056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N (1990) Linkage strategies for genetically complex traits. I. Multilocus models. Am J Hum Genet 46:222–228 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risch N, Merikangas K (1996) The future of genetic studies of complex human diseases. Science 273:1516–1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder K, Bacanu SA, Sonpar V, Zhang X, Devlin B (2005) Analysis of single-locus tests to detect gene/disease associations. Genet Epidemiol 28:207–219 10.1002/gepi.20050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatti C, Service S, Freimer N (2003) False discovery rate in linkage and association genome screens for complex disorders. Genetics 164:829–833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satagopan JM, Elston RC (2003) Optimal two-stage genotyping in population-based association studies. Genet Epidemiol 25:149–157 10.1002/gepi.10260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell JL, Heston LL, Sommer SS (1993) Novel association approach for determining the genetic predisposition to schizophrenia: case-control resource and testing of a candidate gene. Am J Med Genet 48:28–35 10.1002/ajmg.1320480108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD (2002) A direct approach to false discovery rates. J R Stat Soc B 64:479–498 10.1111/1467-9868.00346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Taylor JE, Siegmund D (2004) Strong control, conservative point estimation, and simultaneous conservative consistency of false discovery rates: a unified approach. J R Stat Soc B 66:187–205 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2004.00439.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R (2003) Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:9440–9445 10.1073/pnas.1530509100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terwilliger JD, Speer M, Ott J (1993) Chromosome-based method for rapid computer simulation in human genetic linkage analysis. Genet Epidemiol 10:217–224 10.1002/gepi.1370100402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DC, Haile RW, Duggan D (2005) Recent developments in genomewide association scans: a workshop summary and review. Am J Hum Genet 77:337–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD (2002) Modern applied statistics with S, 4th ed. Springer Verlag, New York [Google Scholar]