Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: Cell cycle arrest by transforming growth factor-β and its disruption in cancer (original) (raw)

Abstract

Altered responsiveness to extracellular signals and cell cycle dysregulation are hallmarks of cancer. The cell cycle is governed by cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) that integrate mitogenic and growth inhibitory signals. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β mediates G1 cell cycle arrest by inducing or activating cdk inhibitors, and by inhibiting factors required for cdk activation. Mechanisms that lead to cell cycle arrest by TGF-β are reviewed. Loss of growth inhibition by TGF-β occurs early in breast cell transformation, and may contribute to breast cancer progression. Dysregulation of cell cycle effectors at many different levels may contribute to loss of G1 arrest by TGF-β. Elucidation of these pathways in breast cancer may ultimately lead to novel and more effective treatments for this disease.

Keywords: breast cancer, cell cycle, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor, human mammary epithelial cells, transforming growth factor-β

Introduction

TGF-β is a potent inhibitor of mammary epithelial cell proliferation [1,2] and regulates mammary development in vivo [3,4,5]. Mammary-specific overexpression of TGF-β in transgenic mice can induce mammary hypoplasia and inhibit tumourigenesis [6,7,8]. Although normal human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) are exquisitely sensitive to TGF-β [9], human breast cancer lines require 10-fold to 100-fold more TGF-β to produce an antimitogenic response, and some show complete loss of this effect [10].

Although loss of growth inhibition by TGF-β in human cancers can arise through loss of TGF-β production or through mutational inactivation of the TGF-β receptors and Smad signalling molecules [11,12], these defects are not observed in most arrest-resistant cancer lines. This observation, and the frequent appearance of resistance to more than one inhibitory cytokine in human tumours [13] emphasize the importance of the cell cycle effectors of growth arrest induced by TGF-β as targets for inactivation in cancer.

TGF-β can either lengthen G1 transit time or cause arrest in late G1 phase [14]. This cell cycle arrest is usually reversible [15,16], but in some cases is associated with terminal differentiation [17,18,19]. Because TGF-β arrests susceptible cells in the G1 phase, a brief review of cell cycle regulation is presented. This is followed by a review of the multiple and often, complementary mechanisms that contributing to G1 phase arrest by TGF-β and of how they are disrupted in breast and other cancers.

Cell cycle

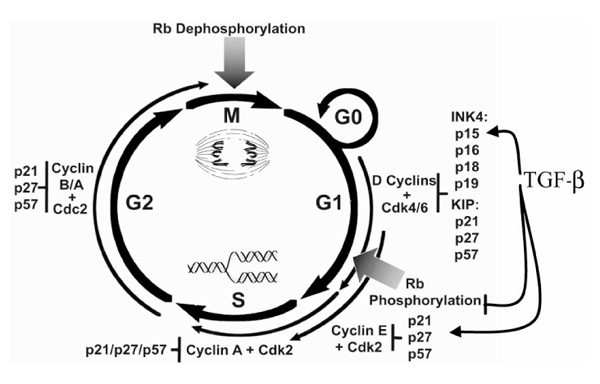

Cell cycle progression is governed by cdks, which are activated by cyclin binding [20,21] and inhibited by the cdk inhibitors [22,23]. The cdks integrate mitogenic and growth inhibitory signals and coordinate cell cycle transitions [24,25]. G1 to S phase progression is regulated by D-type cyclin-, E-type cyclin- and cyclin A-associated cdks (Fig. 1). B-type cyclin-associated kinases govern G2 and M phases. Both E-type and D-type cyclin-cdks contribute to phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein (pRb). Hypophosphorylated pRb binds members of the E2F and DP1 families of transcription factors, inhibiting these transcriptional activators and actively repressing certain genes. Phosphorylation of pRb in late G1 phase liberates free E2F/DP1, allowing activation of genes required for S phase (for review [26]).

Figure 1.

The cell cycle. Cell cycle progression is governed by cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks), the activities of which are regulated by binding of cyclins, by phosphorylation and by the cdk inhibitors [the inhibitor of cdk4 (INK4) family: p15, p16, p18 and p19; and the kinase inhibitor protein (KIP) family: p21, p27 and p57].

Cyclin-dependent kinase regulation by phosphorylation

Cdk activation requires phosphorylation of a critical threonine (Thr160 in cdk2 and Thr187 in cdk4). There are two mammalian kinases with in vitro cdk activating kinase (CAK) activity: cyclin H/cdk7 and the protein encoded by the human homolog of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CAK1, called Cak1p (for review [27]). The specific roles of these two kinases are somewhat controversial. CAK is active throughout the cell cycle [20,28], but its access to cyclin-bound cdks is inhibited by p27 [29]. Cdks are also negatively regulated by phosphorylation of specific inhibitory sites [27]. Cdc25 phosphatase family members must dephosphorylate these inhibitory sites for full cdk activation. Cdc25A acts on cyclin E-bound cdk2 and is required for G1 to S phase progression [30].

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

Two cdk inhibitor families regulate the cell cycle [22,23]. The inhibitor of cdk4 (INK4) family members (p15INK4B, p16INK4A, p18INK4C and p19INK4D) inhibit specifically cdk4 and cdk6. The p16 gene, or MTS1 (Multi-Tumor Suppressor 1), was discovered as a tumour suppressor that is deleted in many cancers [31]. Loss of p15, located near p16 on chromosome 9p, may contribute to loss of G1 arrest by TGF-β (see below).

The kinase inhibitor protein (KIP) family presently consists of three members, p21WAF1/Cip1, p27Kip1 and p57Kip2. The KIPs bind and inhibit a broader spectrum of cdks than do the INK4s. p21 is low in serum-deprived quiescence, but p21 levels and p21 binding to D-type cyclin-cdk complexes increase in early G1 phase. In addition to regulating G1 phase progression, p21 acts to coordinate cell cycle responses to DNA damage [23]. p27Kip1 was first identified as a heat stable protein whose binding to cyclin E-cdk2 complexes that was increased by TGF-β, lovostatin, or contact inhibition [32,33,34,35,36]. p27 is high in G0 and early G1 phase and decreases during G1 to S phase progression. p27 degradation by ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis [37] is activated by many different growth factors and may involve ras pathways [38,39,40,41,42]. Although cyclin E-cdk2 phosphorylates p27 on Thr187 leading to its degradation in late G1 phase [43,44], other kinases may also influence p27 function and/or degradation. The possibility that mitogenic signalling pathways that modulate p27 phosphorylation also oppose Smad activation by TGF-β is the subject of intensive investigation.

Although p21 and p27 inhibit cyclin E-cdk2, they also function in the assembly and activation of cyclin D-cdk4 and cyclin D-cdk6 complexes. KIP-mediated assembly of D-type cyclin-cdks in early G1 phase may facilitate activation of E-type cyclin-cdks through sequestration of KIPs away from cyclin E complexes [45,46].

Mechanisms of cell cycle arrest by TGF-beta

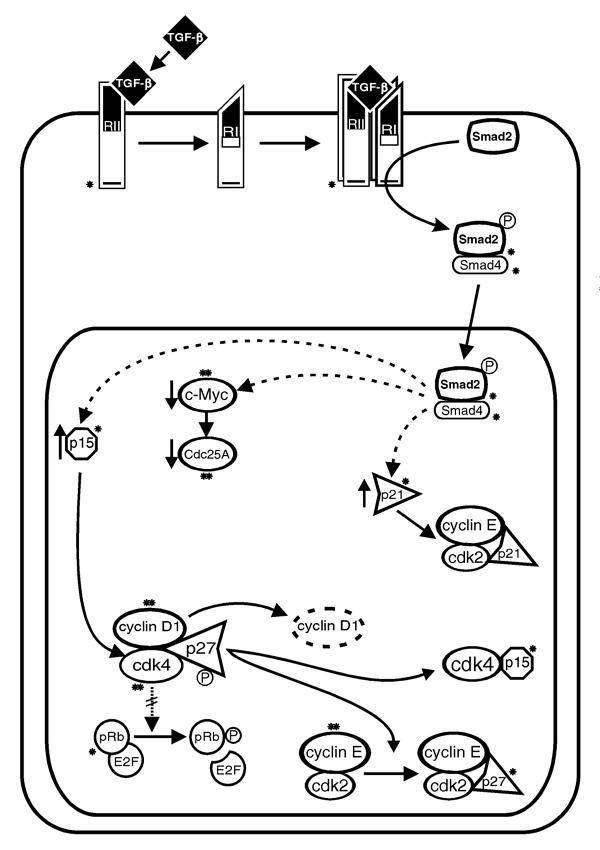

TGF-β inhibits phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma protein

Cells are sensitive to TGF-β during a discrete period in early G1 phase, until they reach a 'restriction point' 6-10 h after G0 release [47,48]. When TGF-β is added after this critical time point, cells complete the cell cycle but arrest during the subsequent G1 phase. Laiho et al [47] observed that TGF-β inhibits pRb phosphorylation when it is added in early G1 phase. This key observation suggested that TGF-β was acting before the G1 to S phase transition to inhibit a pRb kinase, and led to the investigation of TGF-β effects on cell cycle regulators. These studies have shown that TGF-β prevents or inhibits G1 cyclin-cdk activation through multiple mechanisms, leading to pRb dephosphorylation (Fig. 2). E2F activity is also impaired by TGF-β through a decline in E2F mRNA levels [49]. The observation that E2F overexpression can prevent TGF-β-mediated arrest [49] emphasizes the importance of the effects of TGF-β on pRb and E2F.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of cell cycle arrest by transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and their deregulation in cancer. TGF-β receptor activation leads to Smad2 phosphorylation. Phosphorylated Smad2 then binds Smad4 and the Smad2-Smad4 complex translocates to the nucleus to modulate transcription. Although p15 and p21 genes are induced and c-myc and Cdc25A repressed by TGF-β, these may not be direct effects of Smad2-Smad4 action (dotted lines). TGF-β inhibits G1 cyclin-cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks) by increasing p15 binding to cdk4 and cdk6 and by increasing p27 (+/-p21) binding to cyclin E-cdk2, thereby inhibiting retinoblastoma protein (pRb) phosphorylation. *Components of the TGF-β effector pathway that are mutated and/or functionally inactivated in human cancers; **molecules whose activation or overexpression may contribute to TGF-β arrest resistance.

TGF-β downregulates c-myc

In many cell types, TGF-β causes a rapid inhibition of c-myc transcription [2,16,50]. Transcriptional regulation by the c-Myc protein is required for G1 to S phase progression. Downregulation of c-myc by TGF-β is believed to be important for arrest, because c-myc overexpression causes TGF-β resistance [2,51]. Repression of the c-myc gene by TGF-β may directly or indirectly contribute to the loss of G1 cyclins [52,53], to downregulation of Cdc25A [54] and to the induction of the cdk inhibitor p15 [55] (see below).

Effects on G1/S cyclins

TGF-β causes loss of G1 cyclins in a cell-type-dependent manner. Cyclin A expression is downregulated by TGF-β in most cell types [32,56] and a TGF-β-regulated region of the cyclin A promoter has been identified [57]. Effects of TGF-β on cyclin E differ among different cell lines. For example, in HaCat keratinocytes TGF-β decreases both mRNA and protein levels of cyclin A and cyclin E, whereas in HMECs cyclin E mRNA is reduced but protein levels are not [32,56]. Although cyclin D1 levels are decreased by TGF-β in some cell types, this usually occurs late as a consequence of arrest [58,59].

Cooperation between p15 and p27

In epithelial cells, including HMECs, the INK4 and the KIP proteins collaborate to inhibit D-type cyclin-cdks and E-type cyclin-cdks to bring about G1 arrest by TGF-β [60,61]. p_15_INK_4_B was first cloned as a gene upregulated by TGF-β [62] and its induction involves an Sp1 site in the promoter [63]. TGF-β induces p_15_INK_4_B and stabilizes the p15 protein, leading to p15 binding and inhibition of cdk4 and cdk6. Cyclin D1 and KIP molecules dissociate from cdk4 and cdk6, and p27 accumulates in cyclin E-cdk2 complexes, inhibiting the latter [60,61]. A late downregulation of cyclin D1 and cdk4 follows G1 arrest. TGF-β appears to actively regulate p27's affinity for its targets, independent of p15 function, favouring p27 accumulation in cyclin E complexes [61].

Upregulation of p21 expression

In normal HMECs, TGF-β affects neither p21 levels, nor the binding of p21 to target cdks [61]. In other cell types, TGF-β induction of p21 plays a role in cdk inhibition [59,64,65] and its upregulation is independent of p53 [64,66]. The p21 gene may be a downstream target of Smad4, because transient overexpression of Smad4 induces p21 mRNA [67]. Like p15, the _p_21_WAF_1/_Cip_1 gene promoter contains Sp1 sites that are regulated by TGF-β in reporter gene assays [63,68]. Other cdk inhibitors, p16, p18, p19 and p57, have not to date been implicated in TGF-β-mediated arrest.

Effects on cdk2 phosphorylation

TGF-β also regulates cdk2 phosphorylation. In Mv1Lu cells, TGF-β inhibits cdk2 in part by inhibiting phosphorylation on Thr160 [32,34]. p27 can inhibit CAK access to cyclin-bound cdks in vitro [29]. Thus, TGF-β may prevent CAK action by increasing the binding of p27 to cyclin E-cdk2. In HepG2 cells, however, TGF-β inhibits the enzymatic activity of Cak1p [69], indicating an alternative mechanism for the inhibition by TGF-β of Thr160 phosphorylation of cdk2.

Dephosphorylation of inhibitory sites on cyclin E-bound cdk2 is required for G1 progression and is required for G1 to S phase progression [30]. In a human breast epithelial line, TGF-β reduced Cdc25A expression in association with an increase in inhibitory cdk phosphorylation [54]. The effect on Cdc25A expression may be secondary to the repression by TGF-β of c-myc, because in some cell types Cdc25A is induced by c-myc [70].

Loss of TGF-beta mediated G1 arrest in cancer

In nontransformed epithelial cells, TGF-β causes G1 arrest through downregulation of c-myc, inhibition of the G1 cdks and hypophosphorylation of pRb. Overlapping or redundant cell cycle controls assure growth arrest. In malignantly transformed cells, however, this redundancy is often lost and carcinoma-derived cells are usually refractory to growth inhibition by TGF-β [10]. Indeed, in advanced cancers, TGF-β may promote tumour growth and metastatic progression [71]. In this part of the discussion, we review how dysregulation of many different cell cycle mechanisms abrogate TGF-β arrest in cancer (Fig. 2).

Altered cdk inhibitor expression and function

Dysregulation of the INK4 family may contribute to TGF-β resistance in cancer. In human tumours, deletion of p15 often accompanies p16 deletion due to their proximity on chromosome 9p [72,73,74]. Silencing of p15 through promoter hypermethylation, which is observed in leukaemias, is associated with loss of TGF-β sensitivity [75,76]. In other TGF-β-resistant cells, however, p15 protein levels may increase normally, indicating that, at least in these lines, a functional p15 is not sufficient to mediate arrest by TGF-β [65].

Although p15 and p27 cooperate to inhibit the G1 cyclin-cdks in normal cells, neither of these cdk inhibitors are essential for G1 arrest by TGF-β. p15 is clearly not essential for TGF-β-mediated G1 arrest, because cells bearing p15 deletions can respond through upregulation of p21 and p27 [59,65], or downregulation of Cdc25A [54]. Lymphocytes from p27-null mice can still arrest in response to TGF-β [77]. Nonetheless, the requirement for p27 in arrest by TGF-β may differ in normal and transformed cells. Although inhibition of p27 expression through antisense p27 oligonucleotide transfection did not abrogate TGF-β-mediated arrest in finite lifespan HMECs, it did do so in breast cancer-derived lines (Donovan J, Slingerland J, unpublished data). In normal cells, multiple redundant pathways cooperate to mediate arrest, but in cancer cells the progressive loss of other checkpoints may make p27 indispensable for TGF-β-mediated arrest.

The antiproliferative role of p27 is frequently disrupted in human cancers. Although mutations in p27 are rare [78,79], accelerated proteolysis causes reduced p27 protein in many cancers, including breast, and may contribute to TGF-β resistance [37,80,81,82]. Less often, primary tumours may exhibit strong cytoplasmic p27 expression associated with poor prognosis. Cytoplasmic p27 has been observed in some advanced cancer-derived lines [83]. Thus, some cancers may express a stable but inactivated p27. In a TGF-β-resistant HMEC line, we have observed stable cytoplasmic p27 localization, altered p27 phosphorylation and impaired binding of p27 to cyclin E-cdk2 (Ciarallo S, Slingerland J, unpublished data). The elucidation of how of mitogenic signalling pathways alter p27 inhibitor function may prove important insights into mechanisms of TGF-β resistance (see below).

Altered KIP function has also been observed in TGF-β-resistant prostate cancer cells. Although TGF-β caused an upregulation in p21-cdk2 binding, this kinase was not inhibited, suggesting that p21 may not function normally in these cells [84]. Loss of p21 has also been observed in advanced breast cancers in association with a poor patient prognosis [85,86]. As for p27, functional inactivation of p21 could contribute to TGF-β resistance during breast cancer progression.

Cyclin overexpression and TGF-β resistance

Overexpression and/or amplification of the cyclin D1 gene is seen in up to 40% of breast cancers [87,88] and could contribute to TGF-β resistance. Indeed, cyclin D1 transfection of an oesophageal epithelial line conferred resistance to TGF-β [89]. Increased cyclin E protein has also been observed in breast cancers [80,90]. Constitutive overexpression of cyclin E does not confer TGF-β resistance in Mv1Lu cells, however (Slingerland J, Reed S, unpublished data). Pathways that link impaired cyclin degradation with loss of cell cycle responses to TGF-β have yet to be elucidated.

Cdk4 gene amplification and activating mutation

Although loss of cdk4 does not contribute significantly to arrest by TGF-β because it occurs after most cells have entered G1 phase [60], ectopic cdk4 expression can abrogate TGF-β-mediated arrest [91]. The increased cdk4 level may exceed titration by p15 and, in addition, sequestration of KIPs away from cyclin E-cdk2 into newly formed cyclin D-cdk4 complexes may lead to loss of cdk2 inhibition. Overexpression of cdk4 may contribute to TGF-β resistance in human cancers. Amplification of the cdk4 gene occurs in primary breast cancers [92] and dominant active cdk4 mutations have been observed in human malignant melanoma [31].

Activation of c-myc, and TGF-β resistance

TGF-β arrest-resistant cells often fail to downregulate c-myc [65]. Moreover, oncogenic activation of c-myc, which is seen in a number of human malignancies, including breast cancer, may impair TGF-β responsiveness through a number of mechanisms.

Overexpression of c-Myc may increase G1 cyclin levels. c-Myc may regulate indirectly the expression of cyclins D1, E and A [52,53]. c-Myc induction of cyclin D1 or cyclin D2 may lead to the sequestration of p27 and p21 away from cyclin E-cdk2, and thus contribute to cyclin E-cdk2 activation [93,94]. These effects, however, which are best demonstrated in fibroblast lines, may not be relevant to TGF-β resistance in epithelial cells. In Mv1Lu cells, c-myc overexpression prevents arrest by TGF-β in part by inhibiting p15 induction [55]. c-Myc effects on D-type cyclin expression and cyclin D-cdk4 complex formation were not sufficient to account for loss of the TGF-β response. Thus, repression of p15 by c-Myc may be important in the arrest-resistant phenotype.

Additional mechanisms link c-Myc with cyclin E-cdk2 activation. Overexpression of c-myc can induce a heat labile factor that binds p27 and inhibits its association with cyclin E-cdk2 [95]. This effect is independent of p27 degradation. Although in some cell types cyclins D1 and D2 may be the c-_myc_-induced inhibitors of p27 [93,94], in other models the c-_myc_-induced inhibitor of p27 appears to be independent of D-type cyclins [95].

Oncogenic activation of c-myc may lead to Cdc25A overexpression and loss of TGF-β-mediated repression of Cdc25A [54]. Overexpression of Cdc25A is observed in primary breast cancers and is associated with a poor patient prognosis (Loda M, personal communication). The increased Cdc25A may represent one of the checkpoints whose disruption makes subsequent disruption of p27 function more critical during breast cancer progression.

Activation of Ras and its effector pathways and TGF-β resistance

Overexpression of activated Ras has been shown to abrogate the antimitogenic effects of TGF-β [96]. Mutational activation of ras is common in many human cancers and may be linked to TGF-β resistance through a number of mechanisms. Activated Ras can interfere with TGF-β signalling by altering Smad2 phosphorylation and signal transduction [97]. Moreover, Ras activation can increase cyclin D1 levels through both transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms [38,98,99]. Ras activation also accelerates p27 degradation [40,41], in some models requiring coexpression of Myc [39]. Although ras mutations are not commonly observed in breast cancer, epidermal growth factor (EGF) and ErbB2 overexpression are, and both activate the Ras effector phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase [100]. Oncogenic activation of different ras effector pathways may abrogate p27 function [41,101], contributing importantly to TGF-β resistance.

Regulation of other G1 events by TGF-β

p53 may play a role in the TGF-β response in some cells. In murine keratinocytes, introduction of mutated p53 led to TGF-β resistance, and a correlation between p53 mutation and loss of responsiveness to TGF-β-mediated arrest has been observed in several cancers [102,103,104].

Constitutive expression of mdm2 can give rise to TGF-β resistance. Although the Mdm2 protein binds to p53 to mediate p53 proteolysis, the effects of Mdm2 on TGF-β sensitivity appear to be independent of p53 function, because expression of an Mdm2 mutant that failed to bind p53 also conferred resistance [105]. Because overexpression of Mdm2 occurs in about 73% of breast cancers, this too may play a role in TGF-β resistance in vivo [85,106,107].

Conclusion

During the past decade the anatomy of cell cycle regulation has been 'worked out'. TGF-β-induced G1 arrest occurs through induction of p15 and p21 genes, repression of the c-myc, Cdc25A, cyclin E and cyclin A genes, and an increase in the association of p15, p21 and p27 with target cdks. Inactivation of G1 cyclin-cdks leads to pRb dephosphorylation and E2F inhibition. The discovery of the Smads as both transducers of TGF-β signalling and transcriptional regulators has been a major advance in this field. Mitogenic signalling via ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase has been shown to interfere with Smad activation [11]. It will be of interest to ascertain whether cross-talk with Smads can also negatively regulate components of mitogenic signal transduction pathways. How growth factors and mitogenic pathways influence the transcriptional activation, intracellular localization and degradation of cyclins and cdk inhibitors is only beginning to be mapped. As these mechanisms are elucidated, we will be able to move from the myopic view of cyclin-cdk regulation in the nucleus, to a broader three-dimensional view of cell cycle regulation that encompasses extracellular and cytoplasmic signalling pathways. The next frontiers lie in the cytoplasm and at the gateway of the nuclear pore as we begin to elucidate how TGF-β/Smad signalling interfaces with transducers of mitogenic signals to regulate cyclin-cdk activities.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Slingerland laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript and Ms Sophie Ku for excellent secretarial assistance.

References

- Massague J, Cheifetz S, Laiho M, et al. Transforming growth factor-β. Cancer Surv. 1992;12:81–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrow MG, Moses H. Transforming growth factor β and cell cycle regulation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1452–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel CW, Silberstein GB, van Horn K, Strickland P, Robinson S. TGF-β1-induced inhibition of mouse mammary ductal growth: developmental specificity and characterization. Dev Biol. 1989;135:20–30. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90154-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberstein GB, Daniel CW. Reversible inhibition of mammary gland growth by transforming growth factor-β. Science. 1987;237:291–293. doi: 10.1126/science.3474783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barcellos-Hoff MH, Ewan KB. Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: mammary gland development. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:92–99. doi: 10.1186/bcr40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce DFJ, Johnson MD, Matzui Y, et al. Inhibition of mammary duct development but not alveolar outgrowth during pregnancy in transgenic mice expressing active TGF-β1. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2308–2317. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12a.2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce DF, Gorska AE, Chytil A, et al. Mammary tumor suppression by transforming growth factor β1 transgene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4254–4258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield LM. Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: lessons learned from genetically altered mouse models. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:100–106. doi: 10.1186/bcr41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosobuchi M, Stampfer M. Effects of the transforming growth factor β on growth of human mammary epithelial cells in culture. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1989;25:705–713. doi: 10.1007/BF02623723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fynan TM, Reiss M. Resistance to inhibition of cell growth by transforming growth factor-beta and its role in oncogenesis. Crit Rev Oncogenesis. 1993;4:493–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. TGF-β signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:753–791. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar M. Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: transforming growth factor-β/SMAD signaling defects and cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:107–115. doi: 10.1186/bcr42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerbel RS. Expression of multi-cytokine resistance and multigrowth factor independence in advanced stage metatstatic cancer: malignant melanoma as a paradigm. Am J Pathol. 1992;141:519–524. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. The transforming growth factor-β family. Ann Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.6.1.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipley GD, Pittelkow MR, Wille JJ, Scott RE, Moses HL. Reversible inhibition of normal human prokeratinocyte proliferation by type β transforming growth factor-growth inhibitor in serum-free medium. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2068–2071. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey RJ, Bascom CC, Sipes NJ, et al. Selective inhibition of growth-related gene expression in murine keratinocytes by transforming growth factor beta. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3088–3093. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.8.3088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zentella A, Massague J. Transforming growth factor beta induces myoblast differentiation in the presence of mitogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5176–5180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.11.5176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui T, Wakefield LM, Lechner JF, et al. Type β transforming growth factor is the primary differentiation inducing serum factor for normal human bronchial epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:2438–2442. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jetten AM, Shirley JE, Stoner G. Regulation of proliferation and differentiation of respiratory tract epithelial cells by TGF-β. Exp Cell Res. 1986;167:539–549. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(86)90193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan DO. Principles of Cdk regulation. Nature. 1995;374:131–134. doi: 10.1038/374131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. Inhibitors of mammalian G1 cyclin-dependent kinases. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1149–1163. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.10.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherr CJ, Roberts JM. CDK inhibitors: positive and negative regulators of G1-phase progression. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1501–1512. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray AW. Creative blocks: cell cycle checkpoints and feedback controls. Nature. 1992;359:599–604. doi: 10.1038/359599a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell L. Defects in a cell cycle checkpoint may be responsible for the genomic instability of cancer cells. Cell. 1992;71:543–546. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Kaelin WG. Transcriptional control by E2F. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:99–108. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon MJ, Kaldis P. Regulation of CDKs by phosphorylation. Results Probl Cell Diff. 1998;22:79–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-69686-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon MJ. Activation of the various cyclin/cdc2 proteins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:180–186. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato JY, Matsuoka M, Polyak K, Massague J, Sherr CJ. Cyclic AMP-induced G1 phase arrest mediated by an inhibitor (p27Kip1) of cyclin-dependent kinase 4 activation. Cell. 1994;79:487–496. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draetta G, Eckstein J. Cdc25 protein phosphatases in cell proliferation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1332:M53–M63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(96)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates S, Peters G. Cyclin D1 as a cellular proto-oncogene. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6:73–82. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1995.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland JM, Hengst L, Pan C-H, et al. A novel inhibitor of cyclin-Cdk activity detected in transforming growth factor β-arrested epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3683–3694. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengst L, Dulic V, Slingerland J, Lees E, Reed SI. A cell cycle regulated inhibitor of cyclin dependant kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5291–5294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koff A, Ohtsuki M, Polyak K, Roberts JM, Massague J. Negative regulation of G1 in mammalian cells: inhibition of cyclin E-dependent kinase by TGF-β. Science. 1993;260:536–539. doi: 10.1126/science.8475385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak K, Kato JY, Solomon MJ, et al. p27Kip1, a cyclin-Cdk inhibitor, links transforming growth factor-β and contact inhibition to cell cycle arrest. Genes Dev. 1994;8:9–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyak C, Lee M-H, Erdjument-Romage H, et al. Cloning of p27KIP1, a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and a potential mediator of extracellular antimitogenic signals. Cell. 1994;78:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90572-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingerland J, Pagano M. Regulation of the Cdk inhibitor p27 and its deregulation in cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2000;183:10–17. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200004)183:1<10::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aktas H, Cai H, Cooper GM. Ras links growth factor signalling to the cell cycle machinery via regulation of cyclin D1 and the cdk inhibitor p27Kip1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:3850–3857. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.3850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone G, DeGregori J, Sears R, Jakoi L, Nevins JR. Myc and Ras collaborate in inducing accumulation of active cyclin E/Cdk2 and E2F [published erratum appears in Nature 1997, 387:932]. Nature. 1997;387:422–426. doi: 10.1038/43230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawada M, Yamagoe S, Murakami Y, et al. Induction of p27Kip1 degradation and anchorage independence by Ras through the MAP kinase signaling pathway. Oncogene. 1997;15:629–637. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takuwa N, Takuwa Y. Ras activity late in G1 phase required for p27kip1 downregulation, passage through the restriction point, and entry into S phase in growth factor-stimulated NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5348–5358. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Bellone CJ, Baldassare JJ. RhoA stimulates p27 Kip degradation through its regulation of cyclin E/Cdk2 activity. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3396–3401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.6.3396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlach J, Hennecke S, Amati B. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1. EMBO J. 1997;16:5334–5344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheaff RJ, Groudine M, Gordon M, Roberts JM, Clurman BE. Cyclin E-CDK2 is a regulator of p27Kip1. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1464–1478. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBaer J, Garret M, Steenson M, et al. New functional activities for the p21 family of cdk inhibitors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:847–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Olivier P, Diehl JA, et al. The p21(Cip1) and p27(Kip1) CDK 'inhibitors' are essential activators of cyclin D-dependent kinases in murine fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1999;18:1571–1583. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laiho M, DeCaprio JA, Ludlow JW, Livingston DM, Massague J. Growth inhibition by TGF-β1 linked to suppression of retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Cell. 1990;62:175–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe PH, Draetta G, Leof EB. Transforming growth factor β1 inhibition of p34cdc2 phosphorylation and histone H1 kinase activity is associated with G1/S-phase growth arrest. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1185–1194. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JK, Bassing CH, Kovesdi I, et al. Expression of the E2F1 transcription factor overcomes type beta transforming growth factor-mediated growth suppression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:483–487. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol JA, Stein RW, Moran E, et al. TGF-β1 inhibition of c-myc transcription and growth in keratinocytes is abrogated by viral transforming proteins with pRB binding domains. Cell. 1990;61:777–785. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90188-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrow MG, Kawabata M, Aakre M, Moses H. Overexpression of the c-Myc oncoprotein blocks the growth-inhibitory response but is required for the mitogenic effects of transforming growth factor beta-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3239–3243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen-Durr P, Meichle A, Steiner P, et al. Differential modulation of cyclin gene expression by MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3685–3690. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya HJ, Yoneyama M, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Taniguchi T. IL-2 and EGF receptors stimulate the hematopoietic cell cycle via different signaling pathways: demonstration of a novel role for c-myc. Cell. 1992;70:57–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90533-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iavarone A, Massague J. Repression of the CDK activator Cdc25A and cell-cycle arrest by cytokine TGF-beta in cells lacking the CDK inhibitor p15. Nature. 1997;387:417–422. doi: 10.1038/387417a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner BJ, Blain SW, Seoane J, Massague J. Myc downregulation by transforming growth factor beta required for activation of the p15(Ink4b) G(1) arrest pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5913–5922. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.5913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng Y, Weinberg RA. Transforming growth factor β effects on expression of G1 cyclins and cyclin-dependant protein kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10315–10319. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X-H, Filvaroff EH, Derynck R. Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-induced down-regulation of cyclin A expression requires a functional TGF-beta receptor complex. J Cell Biol Chem. 1995;270:24237–24245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko TC, Sheng HM, Reisman D, Thompson EA, Beauchamp RD. Transforming growth factor-β1 inhibits cyclin D1 expression in intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene. 1995;10:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florenes VA, Bhattacharya N, Bani MR, et al. TGF-β mediated G1 arrest in a human melanoma cell line lacking p15INK4B: evidence for cooperation between p21Cip1 and p27Kip1. Oncogene. 1996;13:2447–2547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynisdottir I, Polyak K, Iavarone A, Massague J. Kip/Cip and Ink4 Cdk inhibitors cooperate to induce cell cycle arrest in response to TGF-β. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1831–1845. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.15.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu C, Garbe J, Daksis J, et al. Transforming growth factor β stabilizes p15INK4B protein, increases p15INK4B-cdk4 complexes and inhibits cyclin D1/cdk4 association in human mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2458–2467. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon GJ, Beach D. p15INK4B is a potential effector of TGF-β induced cell cycle arrest. Nature. 1994;371:257–261. doi: 10.1038/371257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Nichols MA, Chandrasekharan S, Xiong Y, Wang XF. Transforming growth factor beta activates the promoter of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p15INK4B through an Sp1 consensus site. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:26750–26753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto MB, Li Y, Panus JF, et al. Transforming growth factor β induces the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 through a p53 independent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5545–5549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malliri A, Yeudall WA, Nikolic M, et al. Sensitivity to transforming growth factor β1-induced growth arrest is common in human squamous cell carcinoma cell lines: c-MYC down-regulation and p21waf1 induction are important early events. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1291–1304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbendary A, Berchuck A, Davis P, et al. Transforming growth factor β1 can induce CIP1/WAF1 expression independent of the p53 pathway in ovarian cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;12:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KK, Fleming JB, Abramian A, et al. Overexpression of the tumor suppressor gene Smad4/DPC4 induces p21 waf1 expression and growth inhibition in human carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5656–5661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datto MB, Hu PP, Kowalik TF, Yingling J, Wang XF. The viral oncoprotein E1A blocks transforming growth factor beta-mediated induction of p21/WAF1/Cip1 and p15/INK4B. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2030–2037. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagahara H, Ezhevsky SA, Vocero-Akbani AM, et al. Transforming growth factor beta targeted inactivation of cyclin E:cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2) complexes by inhibition of Cdk2 activating kinase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14961–14966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galaktionov K, Chen X, Beach D. Cdc25 cell-cycle phosphatase as a target of c-myc. Nature. 1996;382:511–517. doi: 10.1038/382511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont N, Arteaga CL. Transforming growth factor-β and breast cancer: tumor promoting effects of transforming growth factor-β. Breast Cancer Res. 2000;2:125–132. doi: 10.1186/bcr44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns P, Mao L, Merlo A, et al. Rates of p16 (MTS1) mutations in primary tumors with 9p loss. Science. 1994;265:415–417. doi: 10.1126/science.8023167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cairns P, Polascik TJ, Eby Y, et al. Frequency of homozygous deletion at p16/CDKN2 in primary human tumours. Nature Genet. 1995;11:210–212. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamb A, Shattuch-Eidens D, Eetes R, et al. Analysis of the p16 gene(CDKN2) as a candidate for the chromosome 9p melanoma susceptibility locus. Nature Genet. 1994;8:23–26. doi: 10.1038/ng0994-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batova A, Diccianni MB, Yu JC, et al. Frequent and selective methylation of p15 and deletion of both p15 and p16 in T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res. 1997;57:832–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel B, Guillerm G, Vereecque R, et al. Methylation of the p15(INK4b) gene in myelodysplastic syndromes is frequent and acquired druing disease progression. Blood. 1998;91:2985–2990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K, Ishida N, Shirane M, et al. Mice lacking p27Kip1 display increased body size, multiple organ hyperplasia, retinal dysplasia, and pituitary tumors. Cell. 1996;85:707–720. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata N, Morosetti R, Miller CW, et al. Molecular analysis of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor gene p27Kip1 in human malignancies. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2266–2269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietenpol JA, Bohlander SK, Sato Y, et al. Assignment of human p27Kip1 gene to 12p13 and its analysis in leukemias. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1206–1210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter PL, Malone KE, Heagerty PJ, et al. Expression of cell cycle regulators p27kip1 and cyclin E, alone and in combination, correlate with survival in young breast cancer patients. Nature Med. 1997;3:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan P, Cady B, Wanner M, et al. The cell cycle inhibitor p27 is an independent prognostic marker in small (T1a,b) invasive breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1259–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catzavelos C, Bhattacharya N, Ung YC, et al. Decreased levels of the cell cycle inhibitor p27Kip1 protein: prognostic implications in primary breast cancer. Nature Medicine. 1997;3:227–230. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orend G, Hunter T, Ruoslahti E. Cytoplasmic displacement of cyclin E-cdk2 inhibitors p21Cip1 and p27Kip1 in anchorage-independent cells. Oncogene. 1998;16:2575–2583. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano SC, Chen YQ. Insensitivity to growth inhibition by TGF-beta1 correlates with a lack of inhibition of the CDK2 activity in prostate carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 1998;17:1949–1556. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M, Shao Z-M, Wu J, et al. p21/waf1/cip1 and mdm-2 expression in breast carcinoma patients as related to prognosis. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:529–534. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971021)74:5<529::AID-IJC9>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsihlias J, Kapusta LR, DeBoer G, et al. Loss of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 is a novel prognostic factor in localized human prostate adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1998;58:542–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammie GA, Fantl V, Smith R, et al. D11S287, a putative oncogene on chromosome 11q13, is amplified and expressed in squamous cell and mammary carcinomas and linked to BCL-1. Oncogene. 1991;6:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MF, Sweeney KJE, Hamilton JA, et al. Expression and amplification of cyclin genes in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 1993;8:2127–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto A, Jiang W, Kim SJ, et al. Overexpression of human cyclin D1 reduces the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) type II receptor and growth inhibition by TGF-beta 1 in an immortalized human esophageal epithelial cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:11576–11580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.24.11576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen N, Arnerlov C, Emdin S, Landberg G. Cyclin E overexpression, a negative prognostic factor in breast cancer with strong correlation to estrogen receptor status. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:874–880. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1996.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewen ME, Sluss HK, Whitehouse LL, Livingston DM. TGF-β inhibition of cdk4 synthesis is linked to cell cycle arrest. Cell. 1993;74:1009–1020. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An H-X, Beckmann MW, Reifenberger G, Bender HG, Niederacher D. Gene amplification and overexpression of Cdk4 in sporadic breast carcinomas is associated with high tumor cell proliferation. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:113–118. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65257-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Roger I, Kim SH, Griffiths B, Sweing A, Land H. Cyclins D1 and D2 mediate Myc-induced proliferation via sequestration of p27Kip1 and p21 Cip1. EMBO J. 1999;18:5310–5320. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard C, Thisted K, Maier A, et al. Direct induction of cyclin D2 by Myc contributes to cell cycle induction and sequestration of p27. EMBO J. 1999;18:5321–5333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlach J, Hennecke S, Alevizopoulos K, Conti D, Amati B. Growth arrest by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 is abrogated by c-Myc. EMBO J. 1996;15:6595–6604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filmus J, Zhao J, Buick RN. Overexpression of H-ras oncogene induces resistance to the growth- inhibitory action of transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGF-beta 1) and alters the number and type of TGF-beta 1 receptors in rat intestinal epithelial cell clones. Oncogene. 1992;7:521–526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar M, Doody J, Timokhina I, Massague J. A mechanism of repression of TGFbeta/Smad signaling by oncogenic Ras. Genes Dev. 1999;13:804–816. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng M, Sexl V, Sherr CJ, Roussel MF. Assembly of cyclin D-dependent kinase and titration of p27Kip1 regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK1). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1091–1096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl JA, Cheng M, Roussel MF, Sherr CJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta regulates cyclin D1 proteolysis and subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3499–3511. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.22.3499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ram TG, Ethier SP. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase recruitment by p185erbB-2 and erbB-3 is potently induced by neu differentiation factor/heregulin during mitogenesis and is constitutively elevated in growth factor-independent breast carcinoma cells with c-erbB-2 gene amplification. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:551–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan P, Babbage JW, Burgering BMT, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase couples the interleukin-2 receptor to the cell cycle regulator E2F. Immunity. 1997;7:679–689. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80388-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwin BI, Spillare E, Forrester K, et al. Mutant p53 can induce tumorigenic conversion of human bronchial epithelial cells and reduce responsiveness to a negative growth factor, transforming growth factor β1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:2759–2763. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss M, Vellucci VF, Zhou ZL. Mutant p53 tumor suppressor gene causes resistance to transforming growth factor beta 1 in murine keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 1993;53:899–904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyllie FS, Dawson T, Bond JA, et al. Correlated abnormalities of transforming growth factor-β1 response and p53 expression in thyroid epithelial cell transformation. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;76:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90255-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun P, Dong P, Dai K, Hannon GJ, Beach D. p53-independent role of MDM2 in TGF-beta 1 resistance. Science. 1998;282:2270–2272. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueso-Ramos CE, Manshouri T, Haidar MA, et al. Abnormal expression of MDM-2 in breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;37:179–188. doi: 10.1007/BF01806499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther T, Schneider-Stock R, Rys J, Niezabitowski A, Roessner A. p53 gene mutations and expression of p53 and mdm2 proteins in invasive breast carcinoma. A comparative analysis with clinicopathological factors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1997;123:388–394. doi: 10.1007/s004320050076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]