ShcA Mediates the Dominant Pathway to Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Activation during Early Thymic Development (original) (raw)

Abstract

During thymic development, the β selection checkpoint is regulated by pre-T-cell receptor-initiated signals. Progression through this checkpoint is influenced by phosphorylation and activation of the serine/threonine kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2, but the in vivo relevance of specific upstream players leading to ERK activation is not known. Here, using mice with a conditional loss of the shc1 gene or expressing mutants of ShcA, we demonstrate that the adapter protein ShcA is responsible for up to 70% of ERK activation in double-negative (DN) thymocytes in vivo and ex vivo. We also identify two specific tyrosines on ShcA that promote ERK phosphorylation in vivo, and mice expressing ShcA with mutations of these tyrosines show impaired DN thymocyte development. This work provides the first in vivo demonstration of the relative requirement of upstream adapters in controlling ERK activation during β selection and suggests a dominant role for ShcA.

T-cell development in the thymus is a complex and ordered process. Precursor cells that commit to the T-cell lineage fate develop into either the αβ or γδ lineage (12, 30, 35, 36, 38). Several steps in the maturation of αβ T cells in the thymus have been recognized. Immature thymocytes that do not express either CD4 or CD8 surface molecules (termed double negative [DN]) progress to express both CD4 and CD8 concurrently (double positive [DP]). DP thymocytes then differentiate into cells expressing either CD4 or CD8 (single positive [SP]).

The DN thymocytes can be further subdivided into at least four distinct developmental stages (DN1, DN2, DN3, and DN4) based on the differential surface expression of CD25 and CD44 molecules: CD25− CD44+ (DN1)→CD25+ CD44+ (DN2)→CD25+ CD44− (DN3)→CD25− CD44− (DN4) (12, 39). Recent studies suggest further subpopulations within the DN1 subset (26). Recombination at the T-cell receptor β (TCR-β) locus is initiated during the DN2 stage. Successful rearrangement at the TCR-β locus results in expression of TCR-β protein, which forms a heterodimer with the pre-Tα chain and appears on the surface as a pre-TCR. Signaling via the pre-TCR at the DN3 stage (termed “β selection”) provides cues for maturation to the DN4 and DP stages. It has not been established whether DN4 represents a transitional cell type on its way to becoming DP or a cell type that receives/responds to signals via the pre-TCR and additional cues.

Phosphorylation and activation of the serine/threonine kinases extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) and ERK2 (collectively referred to here as ERK) have been shown to be important for DN thymocyte maturation. Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation via drugs that affect upstream kinases (Mek1) or dominant negative forms of Mek1 blocks thymocyte maturation at the DN3 stage (5). Moreover, forced expression of activated Ras or activated Raf, which leads to ERK activation, promotes maturation of DN thymocytes to the DP stage in the pre-TCR deficient RAG−/− mice (9, 10). A recent study in which both _erk1_and erk2 genes were deleted within thymic subpopulations revealed a key role for ERK1/2 proteins at the β selection checkpoint (7). That study and other studies suggest a role for ERK at least through the DN4 stage of development.

Activation of the small GTPase Ras and initiation of a Ras-mediated kinase cascade lead to phosphorylation of ERK on specific threonine and tyrosine residues and its subsequent activation. In mature T cells, several adapter proteins have been implicated upstream of Ras/ERK activation (3, 11, 33, 37). These include the adapters LAT, SLP-76, GADS, Shc, and Grb2. Both LAT and Shc can recruit Grb2 and in turn Sos, a Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor, and thereby promote Ras/ERK activation. LAT and SLP-76, through their role in calcium flux via phospholipase C-γ1 (PLC-γ1) can also lead to protein kinase C activation and in turn to downstream activation of a second Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor, Ras-GRP1 (6, 11, 31). The importance of the contributions of these different adapters in regulating ERK activation during thymic development has not been defined. While ablation of LAT, ShcA, and SLP-76 expression in mice results in arrested thymocyte development at the DN3 stage, how they link to ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes is not known (1, 4, 19, 24, 34, 41-43). Ras-GRP1 expression is low in DN cells prior to pre-TCR signaling, and Ras-GRP1 null mice do not have a demonstrable defect in the DN→DP transition (6, 18). Thus, the relative contributions of the different adapters in regulating ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes constitute an important yet unanswered question.

ShcA (encoded by the shc1 gene) is a ubiquitously expressed adapter protein (16, 22, 29) that contains an N-terminal phosphotyrosine-binding (PTB) domain, a central proline-rich (CH1) domain, and a C-terminal Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (16). Both the SH2 and PTB domains of ShcA can bind phosphorylated tyrosine motifs. In T-cell lines, ShcA can be recruited to the TCR complex either via the Shc-SH2 domain binding to phosphorylated TCR-ζ chain (28) or via the Shc-PTB domain binding to tyrosine-phosphorylated ZAP-70 (20) or Lck (8). In DN thymocytes (and in mature T cells), ShcA becomes phosphorylated on three tyrosine residues, Y239, Y240, and Y317, within the CH1 domain. This in turn provides a binding motif for SH2-containing proteins, such as Grb2 (25, 40, 42). The recruitment of Grb2:Sos and the subsequent activation of the Ras/ERK pathway has been implicated as one mechanism of Shc-mediated downstream signaling (32). A ShcA protein carrying mutations of all three tyrosines (ShcFFF) is nonfunctional and has a potent dominant negative effect in T-cell activation (21, 25, 27).

Here we report that ShcA is required for up to 70% of ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes. Using mice lacking ShcA expression or mice expressing tyrosine mutants of ShcA, we demonstrated that ERK activation critically requires ShcA protein expression as well as two specific tyrosine residues on ShcA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

The inducible ShcFFF transgenic mouse line has been described previously (42). The three new inducible ShcA transgenic mouse lines (ShcWT, ShcF317, and ShcFF239/240) were generated by subcloning of the relevant cDNA into the inducible vector, followed by injection of pronuclei (42). Three independent transgenic founders were identified for each of the ShcWT, ShcF317, and ShcFF239/240 transgenes. After initial characterization, where all of the founders for a given transgene showed a comparable phenotype, the data from one of each of the ShcA transgenic lines are presented in this paper. Mice were bred and maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the University of Virginia animal facility according to approved protocols. For Southern blotting to track Cre-mediated excision of the STOP cassette, genomic DNA extracted from sorted thymocyte subsets was first digested with SstI enzyme, run on 1% agarose gel, transferred to a nylon membrane, and detected with the full-length transgenic cDNA as a probe.

Flow cytometry.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from 4- to 6-week-old mouse thymi, and 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells were stained with a saturating concentration of antibody at 4°C for 30 min in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin and 0.05% NaN3, followed by washing to remove the unbound antibody. Reagents used in the analysis included the following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated antibodies: anti-CD3ɛ, anti-CD8α, anti-CD44, anti-CD25, and anti-TCRβ (H57-597). Phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies included anti-CD4, anti-CD25, and anti-CD44. Allophycocyanin-conjugated antibodies included anti-CD44, anti-CD25, and anti-CD4. Biotinylated antibodies included anti-CD3ɛ, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, and anti-mouse lineage marker (anti-CD3ɛ, anti-TER-119, anti-GR-1, anti-CD11β, and anti-B220). Biotin-conjugated monoclonal antibodies were detected using streptavidin-FITC and streptavidin-CyChrome, streptavidin-Peridinin chlorophyll, and streptavidin-allophycocyanin (BD PharMingen). For intracellular staining of ShcA, cells were fixed and permeabilized using the Cytoperm/Cytofix kit (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions and then stained for PE-linked anti-Shc (Santa Cruz, clone PG-97). Gating on surface marker expression was used to assess ShcA expression levels within the different thymic subsets. Cells were analyzed on FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson), using the CELLQuest program and the FlowJo software.

p-ERK analysis by flow cytometry.

Freshly isolated thymocytes were immediately fixed for 10 min at room temperature in RPMI 1640 containing 2% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Services, PA). Cells were then permeabilized in 90% methanol at 4°C for 1 hour, washed twice in cold phospho-buffer (PBS, 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 0.05% NaN3 plus protease and phosphatase inhibitors) to remove the methanol, and then resuspended in phospho-buffer for rehydration. After centrifugation, 0.05 μg of antibody per well in 50 μl of antibody mix for ERK (Cell Signaling) or phospho-ERK (p-ERK) (anti phospho-p44/42 mitogen-activated protein kinase, Thr202/Tyr204; Cell Signaling) was added and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies were detected with Alexa-647-conjugated goat F(ab′)2 anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen, OR). Thymocytes were stained for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD44 expression and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Prior to stimulation of thymocytes by anti-CD3 cross-linking or phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), the cells were resuspended in cold RPMI 1640 with 1% fetal calf serum at 107 cells per ml and allowed to rest for 1 hour on ice. Cells were then pelleted, resuspended in the same buffer with or without 40 nM PMA, and stimulated for 10 min at 37°C. For anti-CD3 cross-linking, 2 μg/ml of anti-CD3ɛ with 20 μg/ml of F(ab′)2 goat anti-mouse antibody was used for 2 min at 37°C. The stimulations were stopped by addition of 1 ml ice-cold PBS containing phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Cells were then washed and treated for intracellular ERK staining as described above. The specificity of the p-ERK signal induced by PMA was confirmed using the MEK inhibitor UO-126.

To normalize and compare ERK phosphorylation in freshly isolated thymocytes from control versus different ShcA transgenic/shc null mice, we first calculated ERK or phospho-ERK geometric mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values from the total DN, DN3, or DN4 subsets and DP populations. The same geometric MFI values for the p-ERK signal were also estimated in parallel samples after PMA stimulation of the thymocytes. The PMA or total ERK protein MFI values were then used to normalize the p-ERK MFI signal in the freshly isolated thymocytes from different mice. Based on the normalized p-ERK value from two or three independent experiments for each mouse line, the mean and standard deviation were estimated. The statistical significance of the data was assessed by two measures. First, using the FlowJo software and the chi-square test, the histogram profiles of different samples were significantly different (e.g., control mice versus ShcFFF or _shc_fl/fl mice in Fig. 1 or control mice and ShcWT mice in Fig. 3). Second, the difference in the normalized p-ERK value in freshly isolated thymocytes among the different mouse lines was analyzed using the Student t test. The general methodology for p-ERK staining and the nature of the data obtained are consistent with the recent independently published methodologies for p-ERK staining (13, 14).

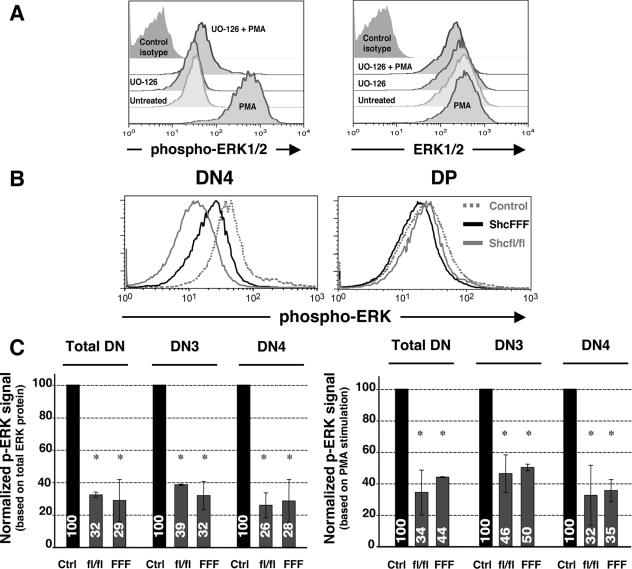

FIG. 1.

Ablation of ShcA expression or ShcFFF transgene expression results in decreased phosphorylation of ERK in DN thymocytes. (A) Detection of phospho-ERK in DN thymocytes. Freshly isolated or PMA-stimulated cells (see Materials and Methods), were analyzed for intracellular phospho-ERK or total ERK protein. Histograms show profiles of phospho-ERK and ERK expression within the DN3 subpopulation assessed by flow cytometry. (B) Histograms showing ERK phosphorylation profiles in DN4 and DP subsets within control, _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF, and _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice. (C) Normalized MFI values for the control, _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF, and _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice. Bar graphs represent mean ratios ± standard deviations derived from three independent experiments.

FIG. 3.

Specific ShcA tyrosine residues differentially influence thymocyte numbers. (A) The schematic depicts the four different Shc transgenic constructs used to generate the transgenic mice. The schematic at the bottom shows the inducible transgenic strategy as described previously (42). (B) Comparison of thymic cellularity between _lck_-Cre/Shc transgenic mice and age-matched controls from multiple independent litters. Control mice included single transgenic mice carrying only the ShcA transgenes or _lck_-Cre alone. Thymocyte numbers in _lck_-Cre/ShcFF239/240 mice were statistically significant compared to those in _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF (P < 0.01) or _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl (P < 0.05) mice. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

Thymocytes were subjected to lysis in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 10 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 10 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 10 mM each of pepstatin, leupeptin, aprotinin, and 4-(2-aminoethyl) benzene sulfonyl fluoride hydorchloride (AEBSF). Immunoprecipitations were performed using anti-Flag-coated agarose beads (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) or anti-Shc polyclonal antibody (Transduction Labs, Lexington, KY) plus protein A-Sepharose beads. Precipitates were washed four times with buffer containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4); 150 mM NaCl; 1 mM each of aprotinin, leupeptin, pepstatin, and AEBSF; 5 mM sodium fluoride; 1 mM sodium orthovanadate;10% glycerol; and 0.1% NP-40. Total cell lysates or immunoprecipitates were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and phosphorylated ShcA was detected by antiphosphotyrosine antibody RC20H (Transduction Lab, Lexington, KY). ShcA and β-actin proteins were detected by immunoblotting with the respective antibodies. Tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins in total lysates were detected by antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody 4G10. All immunoblots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Immunofluorescence staining.

Harvested thymi were embedded in OCT compound and snap frozen on liquid nitrogen. Four-micrometer-thick frozen sections were fixed in acetone for 15 min, air dried for 30 min, and rehydrated in PBS. Tissue sections were blocked with 2% normal mouse serum for 15 min at room temperature and then stained for 60 min at room temperature with appropriate fluorochrome-linked antibodies (CD25-PE [e-biosciences, San Diego, CA] and pan-cytokeratin-FITC [Sigma, St. Louis, MO]). After incubation, slides were washed three times in PBS and then mounted with GelMount, including a 1:10,000 DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) dilution, and viewed on a Zeiss Axioskop 2 MOT microscope (Zeiss, Frankfurt, Germany). Pictures were taken using a Hamamatsu Orca ER digital camera (Hamamatsu-City, Japan).

RESULTS

Requirement of ShcA in regulating ERK activation in DN thymocytes.

While multiple T-cell adapters have been thought to function upstream of ERK based on studies with mature T cell lines, their relative importance in vivo during thymic development has not yet been determined. To examine the potential role of ShcA in ERK activation in DN thymocytes, we examined the status of ERK phosphorylation in mice with a conditional loss of ShcA expression. The _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice were generated by crosses between mice carrying floxed shc1 loci (_shc_fl/fl) (42) and _lck_-Cre mice, where Cre is expressed under control of the _lck_-proximal promoter from the DN1/DN2 stages (15). When we assessed the loss of ShcA expression in the DN subsets after Cre mediated deletion of the shc1 locus by intracellular staining, the signal for ShcA was essentially lost in the DN3 and DN4 subsets of _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice compared to control mice (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). To assess the p-ERK status within the thymic subsets, freshly isolated thymocytes were immediately fixed and stained to detect their p-ERK status in vivo by flow cytometry, along with costaining for surface markers to gate on DN subsets. The specificity of the p-ERK signal detected under these conditions was confirmed using the drug UO-126, as well as a nonspecific isotype-matched control antibody (Fig. 1A). Remarkably, the loss of ShcA expression in the _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice reduced the p-ERK signal in DN thymocytes down to ∼30% of the signal in thymocytes from control _shc_fl/fl mice (Fig. 1B and C). The reduced p-ERK signal in _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl thymocytes was seen in both DN3 and DN4 subsets (Fig. 1C). This suggested that nearly 70% of ERK phosphorylation in the DN3 and DN4 subsets was dependent on ShcA.

It is noteworthy that in the above experiments, we estimated the geometric MFI values of the p-ERK signal in the entire population of DN thymocytes or the DN subsets, due to the difficulty in distinguishing only those thymocytes with loss of ShcA expression under these conditions. However, this may only have led to an underestimation of the potential effects of ShcA on p-ERK activation. As controls, PMA-stimulated maximal ERK phosphorylation and the total ERK protein in the different samples were measured and used in normalizing the samples (see Materials and Methods).

We have previously shown that ShcA can become tyrosine phosphorylated after pre-TCR cross-linking in vivo and in vitro (25). To determine whether the requirement for ShcA in ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes depends on tyrosine phosphorylation of ShcA, we examined _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice (42). These mice inducibly express the dominant negative ShcFFF transgene in which all three of the ShcA tyrosines were mutated, after Cre-mediated removal of the _loxP_-flanked STOP cassette (see schematic of the transgene construct in Fig. 3A). Thymocytes from _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice also showed a reduction in p-ERK in total DN, DN3, and DN4 thymocytes, similar to the case for the _shc_fl/fl mice, suggesting a requirement for the tyrosine phosphorylation sites on Shc. Importantly, the decrease in the p-ERK signal was not seen within the DP subset, which represents “normal” cells that have escaped Cre-mediated deletion of the STOP cassette and therefore develop normally (42) (Fig. 1B). Thus, ∼70% of ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes is dependent on ShcA tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1C).

While the loss of ShcA expression or dominant negative ShcFFF is manifest largely as an arrest at the DN3 stage (42), the phenotype with respect to diminished p-ERK as well as reduced proliferation (unpublished observations) is seen in both DN3 and DN4 thymocytes. This suggests that continued ShcA function through the DN4 stage is required for the DN→DP transition. This correlates with the recent observation that continued ERK protein expression at least through the DN4 stage is important for progression beyond the β selection checkpoint (7). Thus, two different approaches, either loss of ShcA protein expression in the shc fl/fl mice or expression of a dominant negative ShcA in the ShcFFF mice, both suggest a key role for ShcA in leading to ERK phosphorylation in DN3 and DN4 subsets. To our knowledge, this is the first direct demonstration of a role for any adapter molecule in ERK activation at the DN3 and DN4 stages of thymic development.

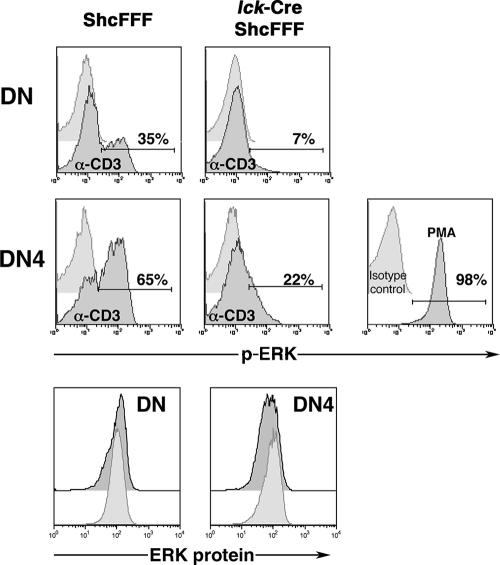

ShcA regulates pre-TCR-mediated ERK phosphorylation ex vivo.

To more directly address the requirement of ShcA tyrosines in CD3-mediated ERK activation in DN thymocytes, we measured ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes after CD3 cross-linking ex vivo (Fig. 2). While the inducible p-ERK signal was detected in 35% of total DN thymocytes in control mice, only 7% of the DN thymocytes from the _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice showed a CD3-induced p-ERK signal. Under these stimulation conditions, we could not detect a CD3-inducible p-ERK signal within the DN3 subpopulation, but the p-ERK signal was readily detectable within the DN4 subpopulation. While 65% of DN4 thymocytes from control mice showed a p-ERK signal, _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice had a severe decrease in the number of p-ERK-positive DN4 thymocytes (22%) (Fig. 2). It is noteworthy that thymocyte populations from the control and the _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice had comparable total intracellular ERK protein levels, and the p-ERK signal after PMA stimulation was readily detectable in thymocytes from _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice (Fig. 2). Taken together, these data further confirmed the requirement for tyrosine phosphorylation of ShcA in CD3-dependent ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes.

FIG. 2.

DN thymocytes from _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice exhibit a defect in CD3-induced ERK phosphorylation. Histogram profiles show the p-ERK signal from the unstimulated (light gray) or anti-CD3-stimulated (dark gray) conditions in total double-negative thymocytes and the DN4 subpopulation. The percentage of p-ERK-positive cells is indicated within the histograms. Comparable PMA-induced p-ERK signals among DN thymocytes from _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice are also shown. The comparable total intracellular ERK protein levels in the control and _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice are shown in the lower panels. The data presented for control and _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice represent pools of two and three mice, respectively, and are similar to data obtained from a separate pool of control and _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF mice.

Specific tyrosines on ShcA differentially influence ERK phosphorylation and thymic development.

To examine the relative significance of the individual ShcA tyrosines in regulating ERK activation and β selection, we produced additional lines of transgenic mice. These mice again were engineered to conditionally express a Flag-tagged ShcA with tyrosine-to-phenylalanine point mutations of Y317 alone (denoted ShcF317), double mutations of Y239 and Y240 residues (ShcFF239/240), or a control wild-type ShcA (ShcWT) (see schematic in Fig. 3A). The conditional transgenic strategy was similar to the one used to express the dominant negative ShcFFF protein used above (42). Upon _lck_-Cre-mediated excision of the STOP cassette, the mice begin to express the transgene-encoded wild-type or the putative dominant negative mutant ShcA proteins in DN thymocytes (Fig. 4C). While data from one founder line for each are presented, we analyzed litters from multiple founder lines, and the phenotypes of the distinct founder lines for the different ShcA transgenes were similar (data not shown). In the absence of Cre, the expression of the transgenic constructs was not detected, and the phenotypes of mice carrying ShcA transgenes alone were indistinguishable from those of control mice.

FIG. 4.

Y239/Y240 tyrosines of ShcA regulate DN thymocyte development. (A) Analysis of thymic subsets based on CD4 versus CD8 (upper panels) or CD44 versus CD25 (lower panels) in ShcWT, ShcF317, ShcFF239/240, and ShcFFF transgenic mice in the _lck_-Cre background. Total thymocyte numbers are indicated on top. (B) STOP cassette deletion in thymocyte subsets and splenocytes analyzed by Southern blotting. The transgenic construct is revealed as a 7.1-kb or a 7.4-kb band (lane 1), while deletion of the STOP cassette by _lck_-Cre/Shc shifts the mobility to a 5.8-kb (ShcWT or ShcF317) or a 6.1-kb (ShcFFF) band. Lanes 1 and 14 show the nondeleted transgenes derived from mice not carrying Cre. These controls were run on the same gel but are placed adjacently here. (C) Lysates of total thymocytes or splenocytes from different ShcA transgenic mice (in the _lck_-Cre background) or a control (ShcFFF mouse without _lck_-Cre) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag monoclonal antibody and immunoblotted with anti-Shc antibody. Membranes were immunoblotted for actin to compare protein loading in the different lanes.

The _lck_-Cre/ShcFF239/240 mice contained significantly fewer total thymocytes than did control mice (three- to fivefold; P < 0.01) (Fig. 3B and Table 1), with an increase in the percentage of DN thymocytes (Fig. 4A). When the DN subsets were further analyzed based on CD44/CD25 expression, there was a readily detectable increase in the fraction of DN3 cells in _lck_-Cre/ShcFF239/240 mice. This suggested a block in thymic development, analogous to the case for the triple tyrosine mutant ShcFFF mice. Notably, the phenotype of ShcFF239/240 mice was less severe than that of the ShcFFF mice or _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice (Fig. 3B and 4A and Table 1), and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). It is noteworthy that this less severe phenotype of the ShcFF239/240 mice was not due to lower expression of the ShcFF protein, as it was expressed comparably to ShcFFF (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). We infer from this result that the presence of an intact Y317 in the ShcFF239/240 mutant construct likely caused the less severe effect than the triple tyrosine mutant. However, when we analyzed mice carrying the single tyrosine mutation of Y317, the _lck_-Cre/ShcF317 mutant mice had no obvious phenotype (Fig. 3B and 4A and Table 1). Thus, under these dominant negative conditions, the presence of Y317 could partially substitute for Y239/Y240 in their absence, while Y239/Y240 appeared to play a greater role in ShcA function during DN thymocyte development. We did not detect a significant difference in the thymocyte numbers or in the distribution of DN or DP subsets in ShcWT mice compared to control mice (Fig. 3B and 4A).

TABLE 1.

Absolute numbers of thymocytes in different mouse linesa

| Genotype (n) | Mean no. of thymocytes ± SD (106) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Double negative (CD4− CD8−) | Double positive (CD4+ CD8+) | Single positive and ISP (CD4+ CD8−, CD4− CD8+) | |

| Littermate control (14) | 132 ± 33 | 6 ± 1.3 | 103 ± 29 | 15 ± 3.2 |

| _lck_-Cre/ShcWT (13) | 139 ± 27 | 8 ± 1.8 | 114 ± 24 | 15 ± 5 |

| _lck_-Cre/ShcF317 (5) | 140 ± 26 | 7 ± 1.9 | 115 ± 23 | 18 ± 2.6 |

| _lck_-Cre/ShcFF239/240 (9) | 61 ± 27 | 6 ± 1.1 | 48 ± 2 | 7 ± 2.7 |

| _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF (11) | 28 ± 7 | 6 ± 1.6 | 21 ± 4 | 4 ± 0.9 |

| _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl (3) | 34 ± 7 | 8 ± 2.5 | 21 ± 5 | 4 ± 1.1 |

When absolute cell numbers were compared, there was no detectable decrease in the number of cells within the DN population among the different mice (Table 1). However, we found a significant decrease in the number of DP and SP cells in ShcFF239/240, ShcFFF, and _shc_fl/fl mice, which correlated with a defect in progression from the DN to the DP compartment. Consistent with these results, we were able to detect deletion of the STOP cassette in DP and SP cells from ShcWT and ShcF317 mice but not ShcFFF mice (Fig. 4B). Thus, while the ShcFFF-expressing cells were selected against proceeding further in development beyond the DN stage, cells expressing ShcWT or ShcF317 were not selected against progression to DP and SP stages of development. Similarly, the transgene-derived protein expression for all of the constructs was detected within the thymocytes, but only the ShcF317 and ShcWT protein expression was detected in the splenocytes, and the expression of ShcFF239/240 and ShcFFF proteins was not detected in the splenocytes (Fig. 4C).

Histological analysis also revealed a defect in thymic development in the ShcFF239/240, ShcFFF, and _shc_fl/fl mice. While the thymi from control, ShcWT, and ShcF317 transgenic mice revealed a densely packed cortex and a large interconnected medullary compartment (less dense area) in the thymi (Fig. 5A), the ShcFF239/240 thymi exhibited scattered and smaller medullary regions, and the ShcFFF and _shc_fl/fl thymi appeared to have medullary regions that were severely decreased in size. CD25 immunofluorescence to focus on the DN2 and DN3 cells revealed their sparse distribution throughout the cortex in control, ShcWT, and ShcF317 mutant mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast, the CD25+ cells are much more densely represented in the ShcFF239/240, ShcFFF, and _shc_fl/fl cortexes, consistent with a block in development at the DN3 stage as suggested by flow cytometry (Fig. 5B). All of these mice displayed a dense cortical and less frequent medullary distribution of stromal cells, as detected by cytokeratin (Fig. 5B). However, consistent with the decreased number of total thymocytes, DAPI staining revealed a decrease in cell density in ShcFF239/240, ShcFFF, and _shc_fl/fl thymi. Taken together, these results suggest that the developmental block at the DN3 stage due to impaired ShcA-mediated signaling leads to aberrant formation of the thymic architecture.

FIG. 5.

Histological analysis of thymi from mice lacking ShcA expression or expressing transgene-encoded mutant ShcA proteins. (A) Defective thymic architecture in ShcFFF- and ShcA-deficient mice. Thymi from control, ShcWT, ShcF317, ShcFF239/240, ShcFFF, and _shc_fl/fl mice (in the _lck_-Cre background) were analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining of frozen sections. Cortex (C) and medulla (M) are indicated for the control thymus. Medullary structure is difficult to discern in the ShcFFF and _shc_fl/fl thymi and is not labeled. (B) Three-color immunofluorescence analysis of thymic sections for CD25 (red), cytokeratin (green), and DAPI (blue). The immunofluorescence data presented (magnification, ×20) are representative of those for at least three mice from the different ShcA transgenic backgrounds and conditional knockout mice in experiments carried out in parallel and are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We next assessed the status of ERK phosphorylation in the different transgenic mice. Thymocytes from ShcFF239/240 mice showed a strong decrease in the p-ERK signal, but this was less severe than in the ShcFFF mice and was statistically significant (P < 0.05; n = 3). In contrast, there was not a detectable effect of ShcF317 on ERK activation (Fig. 6A). While the data presented in Fig. 6A use the total ERK signal for normalization of the p-ERK signal, similar data were obtained when PMA-induced ERK normalization was used (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that mutation of the Y239 and Y240 phosphorylation sites impairs ShcA-dependent ERK activation in DN thymocytes. Moreover, we observed a consistent and statistically significant increase in the p-ERK signal in ShcWT transgenic mice compared to controls (∼40 to 65% increase in the total DN and the DN3 and DN4 subsets). Taken together, these data on ERK activation in vivo correlated nicely with the phenotype of thymocytes in mice expressing different tyrosine mutants of ShcA.

FIG. 6.

Y239/Y240 tyrosine residues of ShcA are critically required for ERK phosphorylation in DN thymocytes. Normalized p-ERK signals in DN thymocytes from _lck_-Cre/ShcWT, ShcF317, ShcFF239/240, and ShcFFF mice are shown. Bar graphs represent means ± standard deviations for three independent experiments. p-ERK signals in total DN, DN3, and DN4 thymic subsets were normalized based either on total ERK expression (A) or on PMA-induced p-ERK signal (B) from the same samples. *, P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

To date, at least three different mechanisms of Ras/ERK activation downstream of the TCR in mature T cells have been proposed: the LAT:Grb2:Sos and Shc:Grb2:Sos pathways (21) and Ras-GRP1 activation downstream of LAT-Gads-SLP-76-mediated PLC-γ1 activation (17). While knockout mice with loss of expression of LAT, SLP-76, and Gads show a clear arrest at the DN3 stage (17, 41, 43), the effects on ERK activation at the DN3 stage have not yet been reported. Examination of the LAT:Grb2:Sos complex in ERK activation is complicated by the additional role of LAT in PLC-γ1→protein kinase C→Ras-GRP1 activation and in regulating other Gads and SLP-76-mediated events (11). Since Ras-GRP1 expression has been reported to occur only after the β selection step (18) and since the phenotype of thymocytes in Ras-GRP null mice suggests a primary role for Ras-GRP1 at the DP stage rather than at the DN stage (6), the PLC-γ1/protein kinase C-dependent Ras-GRP1 activation appear not to affect ERK activation at the DN3 stage. Additionally, in Jurkat cells, Ras-GRP1 activation appears to occur in endomembranes (such as Golgi) (2, 23), and the significance of Ras activation at the plasma membrane versus other cellular subcompartments for thymic β selection is not known. Thus, which of the above modes of Ras/ERK activation is operational and their relative contributions during the β selection checkpoint had been unclear.

While loss of ShcA expression resulted in significant reduction in ERK activation in DN3 and DN4 thymocytes, expression of ShcWT enhanced ERK activation at the same developmental stages. Our data suggest that nearly 70% of ERK activation at the DN3/DN4 stages in vivo depends on ShcA protein and its tyrosine phosphorylation, identifying ShcA as a major player in ERK activation at this developmental stage. When we assessed the loss of ShcA expression in the thymic subsets, the signal for ShcA protein in the total DN, DN3, and DN4 populations in the _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice (either by geometric mean fluorescence intensity or by median channel values) was ∼10 to 18% of that the same population in the control mice. While it is formally possible that the small amount of residual Shc was responsible for the remaining 30% p-ERK signal, it is equally likely that the residual p-ERK signal could have arisen from parallel signals that can also promote ERK activation at the DN3 and DN4 stages. In this regard, the residual p-ERK signal (∼30%) might be mediated by the LAT:Grb2:Sos complex. The reasons for the possible multiple modes of Ras/ERK activation are not understood. It could be that they are additive and thereby enhance the magnitude of ERK activation, that they could work at different stages of thymic development (e.g., Ras-GRP during DP→SP maturation), or that the different modes of activation, perhaps at distinct sites (2), could provide unique signals that are important.

While the _lck_-Cre/ShcWT mice had somewhat higher p-ERK levels within the DN population than control mice, only occasional _lck_-Cre/ShcWT mice showed an increase in total thymocyte numbers compared to control mice. This difference was diluted when data from multiple ShcWT mice were compared and was not statistically significant. However, when we compared the forward scatter profile of the DN4 population in the ShcWT mice, there was a clear increase in the number of larger cells (presumably those that received the pre-TCR signal) in the ShcWT mice (70%, compared to 46% in control mice); in contrast, there was a substantial decrease in larger cells in the ShcFFF and _shc_fl/fl mice, with a concomitant increase in smaller cells (Fig. 7). When we assessed the cell cycle status of the DN subsets from mice with impaired Shc function, we observed a decrease in proliferation of DN3 and DN4 cells. How this might relate to specific transcription factors that have been placed downstream of ERK signaling is currently under investigation.

FIG. 7.

The frequency of larger DN4 cells is diminished in ShcFFF and _shc_fl/fl mice. Forward scatter profiles of gated DN4 thymocytes extracted from control, _lck_-Cre/ShcWT, _lck_-Cre/ShcFFF, and _lck_-Cre/_shc_fl/fl mice are shown. Markers on histogram plots have been set to represent E cells versus L cells.

The block in thymic development due to combined loss of both Erk1 and Erk2 expression was less severe than the phenotype seen with our _shc_fl/fl or ShcFFF mice. There could be at least two possible explanations. In the elegant approach used by Fischer et al. to avoid the embryonic lethality of the Erk2 deficiency, the authors noted the difficulty in fully eliminating Erk2 expression and the variability of the phenotype among the different Erk1/Erk2 doubly deficient mice (7). Alternatively, the difference in phenotype between the ShcA null mice and the Erk null mice could also be because ShcA provides additional signals besides Erk activation (due to divergent pathways activated downstream of Ras, of which Erk is one component). Nevertheless, the data presented here demonstrate that ShcA mediates the dominant pathway leading to ERK phosphorylation in vivo, inhibition of which correlates with the developmental block due to impaired ShcA-mediated signaling.

Supplementary Material

[Supplemental material]

Acknowledgments

We thank Tim Bender and Ulrike Lorenz for discussions and suggestions, Chris Wilson for the lck-Cre transgenic mouse line, and the FACS core facility at the University of Virginia for assistance. We also thank the members of the Ravichandran lab for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (GM55761 to K.S.R.).

Footnotes

▿

Published ahead of print on 18 September 2006.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguado, E., S. Richelme, S. Nunez-Cruz, A. Miazek, A. M. Mura, M. Richelme, X. J. Guo, D. Sainty, H. T. He, B. Malissen, and M. Malissen. 2002. Induction of T helper type 2 immunity by a point mutation in the LAT adaptor. Science 296**:**2036-2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bivona, T. G., I. Perez De Castro, I. M. Ahearn, T. M. Grana, V. K. Chiu, P. J. Lockyer, P. J. Cullen, A. Pellicer, A. D. Cox, and M. R. Philips. 2003. Phospholipase Cgamma activates Ras on the Golgi apparatus by means of RasGRP1. Nature 424**:**694-698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burack, W. R., A. M. Cheng, and A. S. Shaw. 2002. Scaffolds, adaptors and linkers of TCR signaling: theory and practice. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14**:**312-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clements, J. L., B. Yang, S. E. Ross-Barta, S. L. Eliason, R. F. Hrstka, R. A. Williamson, and G. A. Koretzky. 1998. Requirement for the leukocyte-specific adapter protein SLP-76 for normal T cell development. Science 281**:**416-419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crompton, T., K. C. Gilmour, and M. J. Owen. 1996. The MAP kinase pathway controls differentiation from double-negative to double-positive thymocyte. Cell 86**:**243-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dower, N. A., S. L. Stang, D. A. Bottorff, J. O. Ebinu, P. Dickie, H. L. Ostergaard, and J. C. Stone. 2000. RasGRP is essential for mouse thymocyte differentiation and TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol. 1**:**317-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fischer, A. M., C. D. Katayama, G. Pages, J. Pouyssegur, and S. M. Hedrick. 2005. The role of Erk1 and Erk2 in multiple stages of T cell development. Immunity 23**:**431-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima, A., Y. Hatanaka, J. W. Chang, M. Takamatsu, N. Singh, and M. Iwashima. 2005. Lck couples Shc to TCR signaling. Cell Signal. 18**:**1182-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gartner, F., F. W. Alt, R. Monroe, M. Chu, B. P. Sleckman, L. Davidson, and W. Swat. 1999. Immature thymocytes employ distinct signaling pathways for allelic exclusion versus differentiation and expansion. Immunity 10**:**537-546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iritani, B. M., J. Alberola-Ila, K. A. Forbush, and R. M. Perimutter. 1999. Distinct signals mediate maturation and allelic exclusion in lymphocyte progenitors. Immunity 10**:**713-722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordan, M. S., A. L. Singer, and G. A. Koretzky. 2003. Adaptors as central mediators of signal transduction in immune cells. Nat. Immunol. 4**:**110-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kruisbeek, A. M., M. C. Haks, M. Carleton, A. M. Michie, J. C. Zuniga-Pflucker, and D. L. Wiest. 2000. Branching out to gain control: how the pre-TCR is linked to multiple functions. Immunol. Today 21**:**637-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krutzik, P. O., M. R. Clutter, and G. P. Nolan. 2005. Coordinate analysis of murine immune cell surface markers and intracellular phosphoproteins by flow cytometry. J. Immunol. 175**:**2357-2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krutzik, P. O., M. B. Hale, and G. P. Nolan. 2005. Characterization of the murine immunological signaling network with phosphospecific flow cytometry. J. Immunol. 175**:**2366-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee, P. P., D. R. Fitzpatrick, C. Beard, H. K. Jessup, S. Lehar, K. W. Makar, M. Perez-Melgosa, M. T. Sweetser, M. S. Schlissel, S. Nguyen, S. R. Cherry, J. H. Tsai, S. M. Tucker, W. M. Weaver, A. Kelso, R. Jaenisch, and C. B. Wilson. 2001. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity 15**:**763-774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luzi, L., S. Confalonieri, P. P. Di Fiore, and P. G. Pelicci. 2000. Evolution of Shc functions from nematode to human. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10**:**668-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Myung, P. S., G. S. Derimanov, M. S. Jordan, J. A. Punt, Q. H. Liu, B. A. Judd, E. E. Meyers, C. D. Sigmund, B. D. Freedman, and G. A. Koretzky. 2001. Differential requirement for SLP-76 domains in T cell development and function. Immunity 15**:**1011-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norment, A. M., L. Y. Bogatzki, M. Klinger, E. W. Ojala, M. J. Bevan, and R. J. Kay. 2003. Transgenic expression of RasGRP1 induces the maturation of double-negative thymocytes and enhances the production of CD8 single-positive thymocytes. J. Immunol. 170**:**1141-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nunez-Cruz, S., E. Aguado, S. Richelme, B. Chetaille, A. M. Mura, M. Richelme, L. Pouyet, E. Jouvin-Marche, L. Xerri, B. Malissen, and M. Malissen. 2003. LAT regulates gammadelta T cell homeostasis and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 4**:**999-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacini, S., C. Ulivieri, M. M. Di Somma, A. Isacchi, L. Lanfrancone, P. G. Pelicci, J. L. Telford, and C. T. Baldari. 1998. Tyrosine 474 of ZAP-70 is required for association with the Shc adaptor and for T-cell antigen receptor-dependent gene activation. J. Biol. Chem. 273**:**20487-20493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patrussi, L., M. T. Savino, M. Pellegrini, S. R. Paccani, E. Migliaccio, S. Plyte, L. Lanfrancone, P. G. Pelicci, and C. T. Baldari. 2005. Cooperation and selectivity of the two Grb2 binding sites of p52Shc in T-cell antigen receptor signaling to Ras family GTPases and Myc-dependent survival. Oncogene 24**:**2218-2228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pelicci, G., L. Lanfrancone, F. Grignani, J. McGlade, F. Cavallo, G. Forni, I. Nicoletti, T. Pawson, and P. G. Pelicci. 1992. A novel transforming protein (SHC) with an SH2 domain is implicated in mitogenic signal transduction. Cell 70**:**93-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Philips, M. R. 2005. Compartmentalized signalling of Ras. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 33**:**657-661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pivniouk, V., E. Tsitsikov, P. Swinton, G. Rathbun, F. W. Alt, and R. S. Geha. 1998. Impaired viability and profound block in thymocyte development in mice lacking the adaptor protein SLP-76. Cell 94**:**229-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Plyte, S., M. B. Majolini, S. Pacini, F. Scarpini, C. Bianchini, L. Lanfrancone, P. Pelicci, and C. T. Baldari. 2000. Constitutive activation of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway and enhanced TCR signaling by targeting the Shc adaptor to membrane rafts. Oncogene 19**:**1529-1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porritt, H. E., L. L. Rumfelt, S. Tabrizifard, T. M. Schmitt, J. C. Zuniga-Pflucker, and H. T. Petrie. 2004. Heterogeneity among DN1 prothymocytes reveals multiple progenitors with different capacities to generate T cell and non-T cell lineages. Immunity 20**:**735-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt, J. C., M. R. van den Brink, V. E. Igras, S. F. Walk, K. S. Ravichandran, and S. J. Burakoff. 1999. Requirement for Shc in TCR-mediated activation of a T cell hybridoma. J. Immunol. 163**:**2586-2591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ravichandran, K. S., K. K. Lee, Z. Songyang, L. C. Cantley, P. Burn, and S. J. Burakoff. 1993. Interaction of Shc with the zeta chain of the T cell receptor upon T cell activation. Science 262**:**902-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ravichandran, K. S. 2001. Signaling via Shc family adapter proteins. Oncogene 20**:**6322-6330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robey, E. A., and J. A. Bluestone. 2004. Notch signaling in lymphocyte development and function. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 16**:**360-366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roose, J., and A. Weiss. 2000. T cells: getting a GRP on Ras. Nat. Immunol. 1**:**275-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rozakis-Adcock, M., R. Fernley, J. Wade, T. Pawson, and D. Bowtell. 1993. The SH2 and SH3 domains of mammalian Grb2 couple the EGF receptor to the Ras activator mSos1. Nature 363**:**83-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Samelson, L. E. 2002. Signal transduction mediated by the T cell antigen receptor: the role of adapter proteins. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 20**:**371-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommers, C. L., R. K. Menon, A. Grinberg, W. Zhang, L. E. Samelson, and P. E. Love. 2001. Knock-in mutation of the distal four tyrosines of linker for activation of T cells blocks murine T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 194**:**135-142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Starr, T. K., S. C. Jameson, and K. A. Hogquist. 2003. Positive and negative selection of T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 21**:**139-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taghon, T., M. A. Yui, R. Pant, R. A. Diamond, and E. V. Rothenberg. 2006. Developmental and molecular characterization of emerging beta- and gammadelta-selected pre-T cells in the adult mouse thymus. Immunity 24**:**53-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tomlinson, M. G., J. Lin, and A. Weiss. 2000. Lymphocytes with a complex: adapter proteins in antigen receptor signaling. Immunol. Today 21**:**584-591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Boehmer, H. 2005. Unique features of the pre-T-cell receptor alpha-chain: not just a surrogate. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 5**:**571-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Boehmer, H. 2000. T-cell lineage fate: instructed by receptor signals? Curr. Biol. 10**:**R642-R645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walk, S. F., M. E. March, and K. S. Ravichandran. 1998. Roles of Lck, Syk and ZAP-70 tyrosine kinases in TCR-mediated phosphorylation of the adapter protein Shc. Eur. J. Immunol. 28**:**2265-2275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoder, J., C. Pham, Y. M. Iizuka, O. Kanagawa, S. K. Liu, J. McGlade, and A. M. Cheng. 2001. Requirement for the SLP-76 adaptor GADS in T cell development. Science 291**:**1987-1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang, L., V. Camerini, T. P. Bender, and K. S. Ravichandran. 2002. A nonredundant role for the adapter protein Shc in thymic T cell development. Nat. Immunol. 3**:**749-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang, W., C. L. Sommers, D. N. Burshtyn, C. C. Stebbins, J. B. DeJarnette, R. P. Trible, A. Grinberg, H. C. Tsay, H. M. Jacobs, C. M. Kessler, E. O. Long, P. E. Love, and L. E. Samelson. 1999. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity 10**:**323-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[Supplemental material]