A randomized controlled trial of a pharmacist consultation program for family physicians and their elderly patients (original) (raw)

. 2003 Jul 8;169(1):17–22.

Abstract

Background

Pharmacists can improve patient outcomes in institutional and pharmacy settings, but little is known about their effectiveness as consultants to primary care physicians. We examined whether an intervention by a specially trained pharmacist could reduce the number of daily medication units taken by elderly patients, as well as costs and health care use.

Methods

We conducted a randomized controlled trial in family practices in 24 sites in Ontario. We randomly allocated 48 randomly selected family physicians (69.6% participation rate) to the intervention or the control arm, along with 889 (69.5% participation rate) of their randomly selected community-dwelling, elderly patients who were taking 5 or more medications daily. In the intervention group, pharmacists conducted face-to-face medication reviews with the patients and then gave written recommendations to the physicians to resolve any drug-related problems. Process outcomes included the number of drug-related problems identified among the senior citizens in the intervention arm and the proportion of recommendations implemented by the physicians.

Results

After 5 months, seniors in the intervention and control groups were taking a mean of 12.4 and 12.2 medication units per day respectively (p = 0.50). There were no statistically significant differences in health care use or costs between groups. A mean of 2.5 drug-related problems per senior was identified in the intervention arm. Physicians implemented or attempted to implement 72.3% (790/1093) of the recommendations.

Interpretation

The intervention did not have a significant effect on patient outcomes. However, physicians were receptive to the recommendations to resolve drug-related problems, suggesting that collaboration between physicians and pharmacists is feasible.

The advent of effective pharmacologic management of many acute and chronic conditions and the aging population have contributed to increased medication use among elderly patients in particular.1 However, using multiple medications may lead to problems, including inappropriate dosing, drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, therapeutic failure and patient noncompliance.2,3 Studies of elderly patients have estimated that some 6%–28% of hospital admissions or readmissions are attributable to these unintended events.4,5,6,7 Inappropriate prescribing has been detected in the prescriptions of 4%–53% of community-dwelling seniors8,9,10,11,12,13 and is associated with increased risks of hospital admission and emergency department visits.6,7,8

Pharmacists represent a potential, currently underused resource for optimizing the use of medications. Several studies of hospital ambulatory care clinics have shown that a pharmacist consultant can reduce health service use and costs14,15,16 and can improve the appropriateness of drug prescribing for elderly patients.17,18,19 The effectiveness of pharmacist interventions has been demonstrated in 3 recent studies of pharmacists who consulted directly with elderly patients in the pharmacy setting.20,21,22 However, the effectiveness of pharmacist consultants in helping family physicians to manage the drug therapy of their elderly patients has not been reported.

We report the results of a paired cluster randomized controlled trial of specially trained community pharmacists who acted as consultants to primary care physicians after completing drug therapy assessments with senior citizens in the offices of their family physicians. The primary end point was daily units of medication taken, with the intent of reducing regimen complexity and improving patient outcomes.

Methods

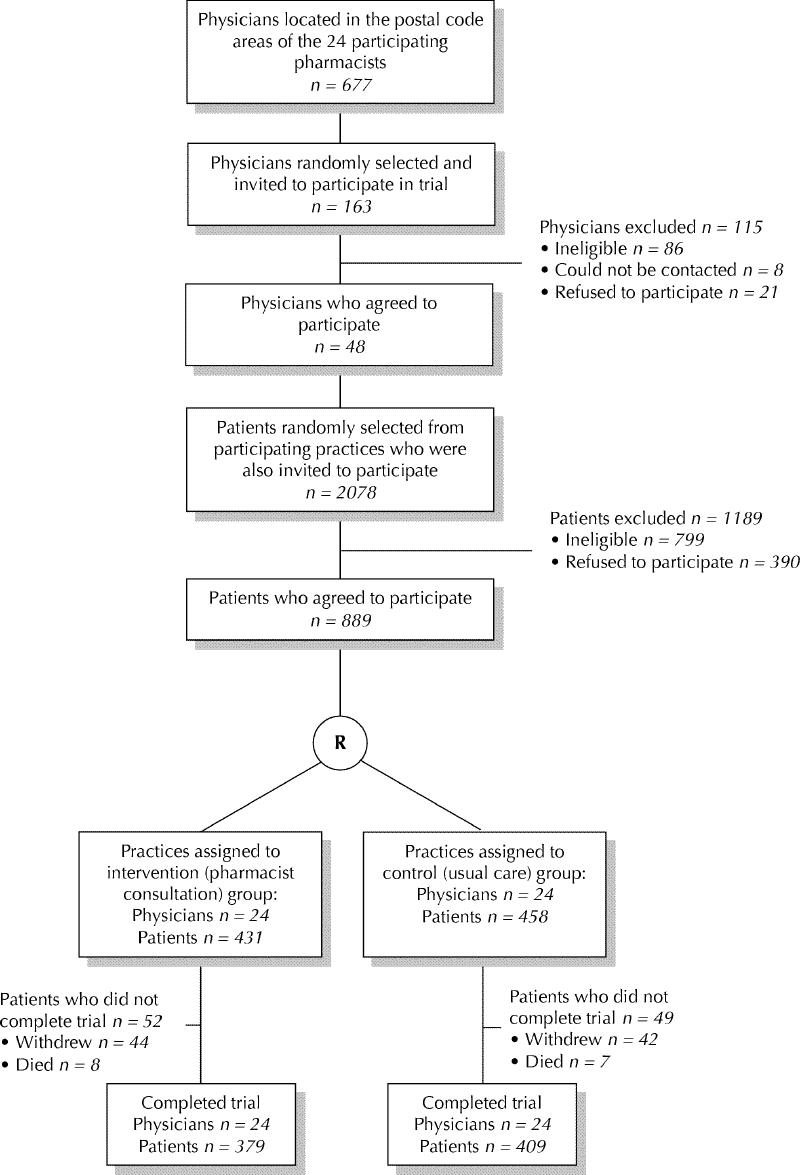

The methods used to recruit community pharmacists, family physicians and their elderly patients have been described elsewhere.23 Briefly, a convenience sample of 24 pharmacists who had received additional post-university training in the prevention, identification and resolution of drug-related problems24 was approached in 16 towns or cities in southern Ontario. All family physicians who practised in each pharmacist's postal code area made up the sampling frame. A random sample of physicians in each postal code area was generated, and physicians were approached by telephone until 2 (1 pair) had been recruited in each area (Fig. 1). About 20 randomly chosen eligible senior citizens per practice (cluster) were recruited (range 7–23 per practice) by the office staff of the practice from August to November 1999. Patients were eligible for inclusion in our study if they were aged 65 years or more, taking 5 or more medications, had been seen by their physician within the past 12 months, had no evidence of cognitive impairment and could understand English. Patients were excluded if they had planned surgery, were on a nursing home waiting list or were receiving palliative care. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Hamilton Health Sciences.

Fig. 1: Flow diagram showing the recruitment of family physicians and patients into the randomized controlled trial. R = randomization.

Before the physicians were randomly allocated, 1 of 8 specially trained research nurses assigned to each practice administered questionnaires designed to collect data on sociodemographic characteristics, medication use and quality of life from the study patients. A list of current and past medical conditions was compiled by the nurse for each patient and confirmed by his or her physician. An ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, ninth revision)25 code was assigned for each diagnosis and reviewed by a family physician (J.S.).

The pair of physicians in each postal code area were randomly allocated, in a concealed fashion, to the intervention or control group, using a central telephone randomization procedure based on computer-generated random numbers (Fig. 1). Randomization was conducted by a research team member (J.K.) who was blinded to the practices' identities. Study patients in practices allocated to the control group received usual care from their physicians. Neither family physicians nor their patients were blinded to their allocation group.

A study patient in a practice randomly allocated to the intervention group had a structured medication assessment by the pharmacist in the physician's office. After the interview, the pharmacist wrote a consultation letter to the physician that summarized the patient's medications, identified drug- related problems and recommended actions to resolve any such problems. The pharmacist subsequently met with the physician to discuss the consultation letter. After the meetings, physicians used a data collection form to indicate which recommendations they intended to implement and when. The pharmacist and physician met again 3 months later to discuss progress in implementing the recommendations. Five months after the initial visit, the pharmacist met with the physician to determine which recommendations had been put in place. One and 3 months after meeting with the physician, the pharmacist monitored each patient's drug therapy using a semistructured telephone interview with the patient.

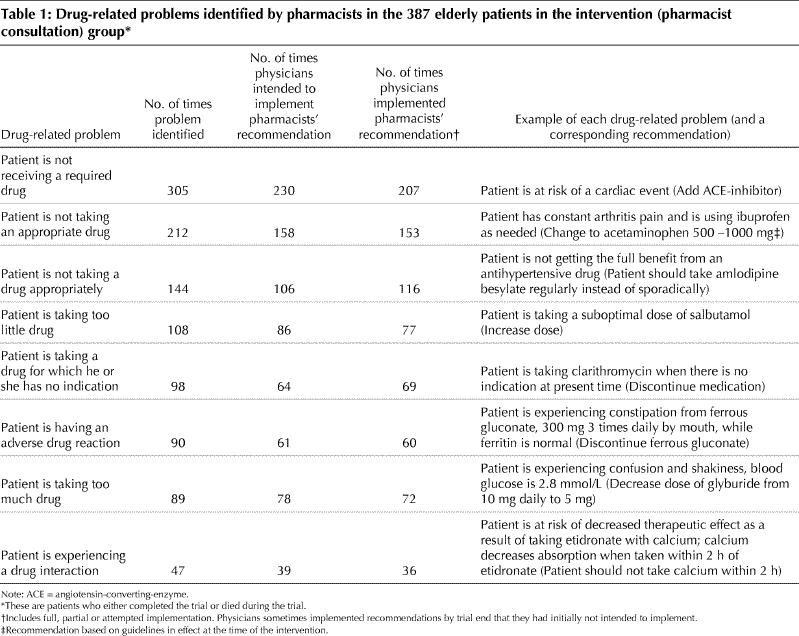

A drug-related problem is defined in pharmaceutical care as any undesirable event experienced by a patient that involved or was suspected of involving drug therapy and that actually or potentially interfered with a desired patient outcome.24 Eight categories of drug-related problems (Table 1) are widely used by pharmacists to administer patient-centred care.18,22,26 The intervention model to identify, resolve and prevent drug-related problems was deemed to be feasible and acceptable for implementation in primary care based on a pilot study with input from family physicians and pharmacists.27 Drug-related problems were determined by the pharmacist consultants using information from the patients' medical charts, the face-to-face interviews and the medication reviews, and they were recorded on a standardized data form.

Table 1

Research nurses interviewed the patients in both groups and recorded their current use of prescribed and over-the-counter medications. The nurses returned to the same practices and requested that the patients not mention whether they had met with a pharmacist. However, the extent to which the research group allocation became known to the nurses was not formally assessed.

The primary end-point measure was a reduction in the daily units of medication taken, as a surrogate for optimized drug therapy. A unit was defined as 1 tablet, 1 teaspoon, 1 drop (eye), 1 application of cream or ointment, or 1 dose of insulin. Other short-term outcome measures that were thought to reflect optimized drug therapy included the costs of medications, health services use, and health-related costs and quality of life.

The number of units and costs of daily prescription and over-the-counter medications were determined for each patient at the beginning and end of the study. Ontario Drug Benefit Program prices were used as the cost of the drugs covered under this plan. All other prices were obtained from a commercial drug wholesaler database or from local pharmacies, if absent from the database. Average daily costs were calculated for all medications.

Information was gathered on the use of health services during the study period from the patients' medical charts and from diaries completed by the patients for health services that would not normally be in the medical charts. Fees for physician services were obtained from the Ontario Schedule of Benefits for Insured Medical Services. The cost of hospital stays and other health services costs were obtained from an area hospital that was participating in the Ontario Case Costing Project (www.occp.com). A hospital stay was considered to be medication-related if it had “probably” or “definitely” resulted from the effects of a medication or medications on a patient's health. To separate hospital stays caused by medication problems from other hospital stays, 2 experts who were unaware of study subjects' allocation (L.D. and a physician) independently assessed each hospital stay as medication-related or not, using a list of the senior's medications and medical conditions at baseline, the reason for admission and the death certificate, if applicable. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion. The Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form (SF-36)28 quality-of-life survey was self-administered at the enrolment and exit interviews.

To evaluate the implementation process within the pharmacist–physician pairs, we also determined physician perception of the service and the extent to which physicians agreed with the recommendations made by the pharmacists for the patients in the intervention arm. In addition, each pharmacist–physician pair jointly assessed whether each recommendation had been implemented (fully or partially) or attempted.

The experimental unit (and the unit of analysis) was the family physician, and the patients were considered to be nested within each physician's practice.29 The desired sample size of 48 physicians with 15 patients per physician was estimated using an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.08 for daily units of medication, based on a pilot study27 and the desire to detect a 15% reduction in daily units of medications in the intervention arm, as compared with the control arm. The hypothesized effect size was based on the results of the pilot study27 and was felt to represent a clinically important reduction in the number of daily medication units. To account for the design, both sample size calculations and the analysis were based on a random effects meta-analysis across cluster pairs, proposed by Thompson and colleagues.30 In this method, the mean differences in the outcome variables between groups are weighted averages of the mean differences across clusters, or practices, and are compared using an asymptotic χ2 test. A one-tailed type I error (alpha) of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests, with a power of 80% to detect the difference.

Results

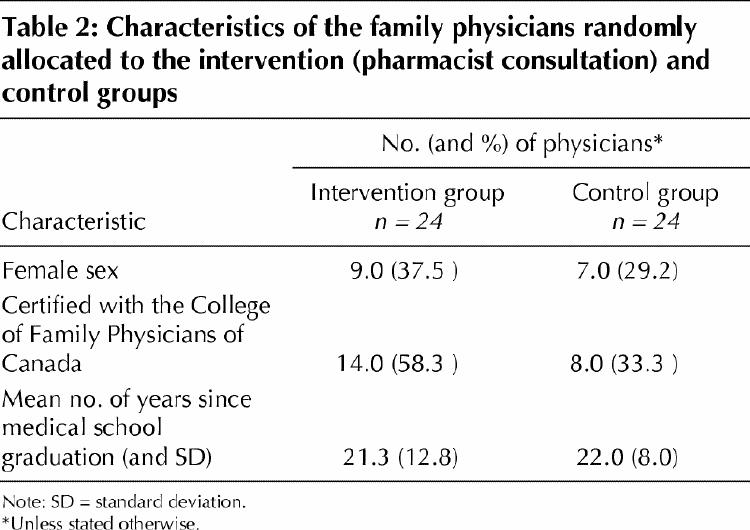

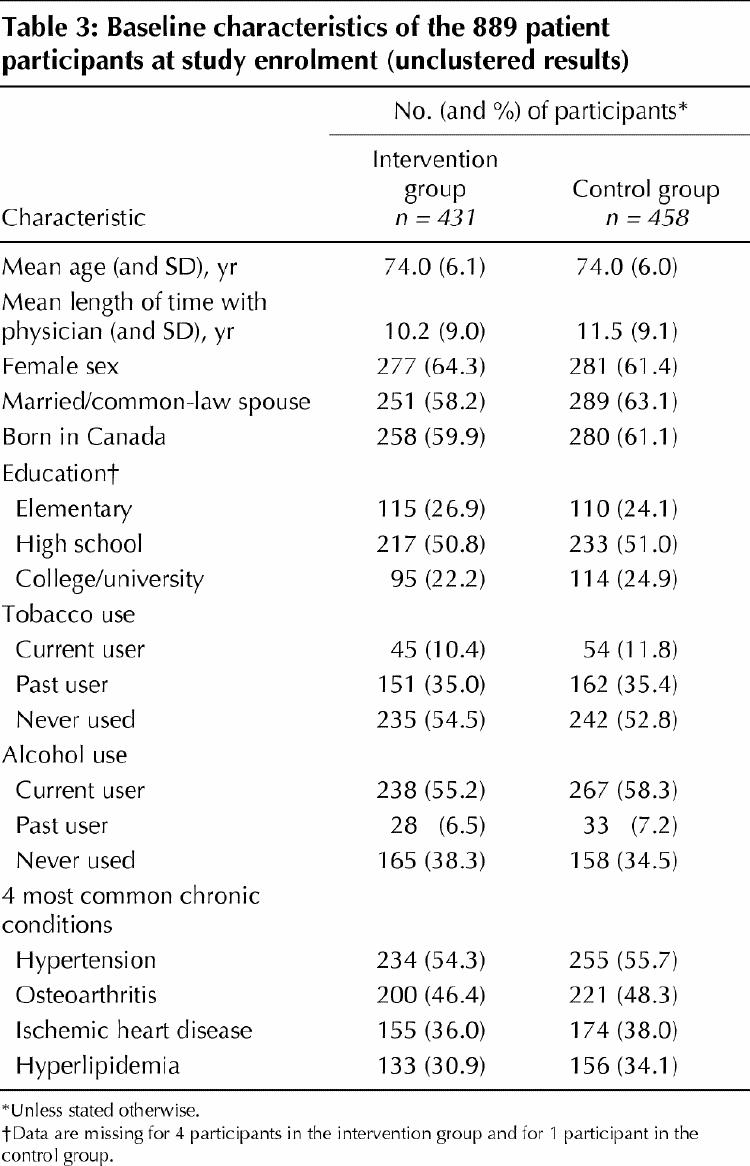

Of the 69 eligible, randomly selected physicians approached, 48 (69.6%) agreed to participate (Fig. 1). The characteristics of physicians in the intervention and control arms of the study are shown in Table 2. In the 48 participating family practices, 1279 eligible, randomly selected seniors were approached and 889 (69.5%) consented to participate (Fig. 1). After random allocation of the physicians, there were 458 seniors in the control group and 431 in the intervention group. The 2 patient groups had similar demographic and medical characteristics and daily medication use (Table 3).

Table 2

Table 3

After 5 months, the mean number of daily prescription and over-the-counter medication units was similar in the intervention and control groups (12.4 v. 12.2, p = 0.50), as was the number of medications taken per day (8.0 v. 7.9, p = 0.87). Daily medication costs were also similar in the 2 groups: 5.01versus5.01 versus 5.01versus4.82 (p = 0.72) for total costs and 3.57versus3.57 versus 3.57versus3.76 (p = 0.78) for costs to the Ontario Drug Benefit Program.

At least 1 drug-related problem was identified by the pharmacists in 79.8% (344/431) of the seniors in the intervention group, with a mean of 2.5 per senior (standard deviation [SD] 2.1, range 0–9). After meeting with the pharmacists, the physicians reported that they intended to implement 76.6% (837/1093) of the pharmacists' recommendations. After 5 months, the physicians had succeeded in fully implementing 46.3% (506/1093) of these recommendations and partially implementing 9.3% (102/1093). For 16.7% (182/1093) of the recommendations, implementation had been attempted but was not successful.

The frequency of the various drug-related problems and examples of recommendations are shown in Table 1. The most common drug-related problem identified was the presence of a condition or risk that was not being treated with a required drug. The average length of meeting with a physician, per patient, was 16.4 (SD 8.1) minutes. Physicians reported that they had learned something new as a result of 53.2% (176/331) of the pharmacist consultations. Perceived-impact forms were not completed by physicians for the consultations concerning the other 48 patients.

Reasons for not fully implementing the recommendations included patient reluctance, a previous attempt and failure of the same strategy recommended by the pharmacist, and the inability to deal with a recommendation within 5 months because other more urgent issues had arisen with the patient.

The mean health care use and associated costs over the study period for the 2 groups appear in Table 4 at www.cmaj.ca. Including the cost of the pharmacist intervention and only drug-related hospital stays, the mean cost of health care resources per senior was 1281.27intheinterventiongroupand1281.27 in the intervention group and 1281.27intheinterventiongroupand1299.37 in the control group (p = 0.45). A decline in the mean scores for health-related quality of life was observed for the seniors in both groups for all of the subscales of the SF-36 quality-of-life survey from baseline to study exit, except for physical functioning in the control group, with no significant differences between the groups (see Table 5 at www.cmaj.ca).

Interpretation

The concept that pharmacists can have a positive impact on patients' drug therapy is becoming widely accepted as a result of encouraging randomized trial evidence.31,32 Although we did not find statistically significant effects of the pharmacist interventions on the number and cost of medications, health care use and cost, or health-related quality of life, the physicians did act on the majority of recommendations made by the pharmacists. This demonstrates that the 2 professional disciplines were able to collaborate to improve the pharmacotherapy of elderly patients.

Several randomized trials have shown that pharmacists with specialized training can improve prescribing16,17,18,19,33 and reduce health care use14,16 and medication costs.16,19 Pharmacist interventions have also been shown to improve clinical measures in patients with hypertension,34,35 hyperlipidemia34,36,37,38 and diabetes.39 However, these findings were limited in their generalizability to pharmacists collaborating with family physicians in their offices. Widespread interventions in primary care with pharmacists with advanced training (PharmD degrees) would not be feasible at this time in Canada because of the small number of individuals trained. Our study examined a generalizable and implementable pharmacist consultation program using resources that already existed in the community.

The results of studies examining the effects of consultations with community pharmacists without specialized training have been inconclusive to date. Pharmacists who have directly interacted with patients in the pharmacy setting have been able to improve cholesterol levels,37 prescribing outcomes21 and compliance.20,21 However, pharmacist interventions were not found to improve clinical measures in patients with reactive airways disease40 or to improve quality of life,20,22 costs, compliance or symptoms in elderly patients.20,21,22,41 A recent Canadian study of a one-time intervention in primary care to decrease potentially inappropriate prescribing failed to show a significant effect using a team consisting of a physician, pharmacist and nurse.42 Pharmacists in our study also assessed seniors' medications once and made one set of recommendations to the physicians, with 2-time patient and 1 in-person physician follow-up. However, more continuous monitoring and intervention to resolve drug-related problems might have strengthened the effectiveness of the intervention. A recent review has noted that pharmacist interventions directed at physicians tend to be less intensive than those directed at patients.32 The mixed results found in the literature may be because it is difficult to show substantial changes over time in elderly patients, despite optimization of pharmacotherapy, or because the measurement instruments being used are not responsive enough to change.43

There were several limitations to our study. In attempting to make our study feasible and generalizable, we may have reduced our ability to detect significant benefits. The eligibility criteria were broad, resulting in a sample with highly variable health status. In addition, a common difficulty in evaluating new health interventions is defining an outcome that can be measured in a reasonable length of time with a manageable sample size, rather than rare events such as mortality. The outcome measure on which we based our sample size, units of medication, was a proxy for a simplified medication regimen that would hopefully have led to fewer interactions, improved compliance and hence improved patient outcomes. Given that the most common recommendation was to add a medication, it is possible that our follow-up time was too brief to capture the impacts of improved drug therapy.

A strength of this study was the high participation rate from both randomly selected physicians and their elderly patients.23 Participating community physicians worked in both rural and urban locations and were not part of academic practices. The local pharmacists did have additional training but were not so different from other community pharmacists that the intervention would not be replicable. In contrast to other models in which pharmacists have directly counselled and managed patients,37,40 the intent of our model was to provide family physicians with an on-site service for their patients. By removing the pharmacists from their pharmacies, we hoped that they would be perceived as health care professionals without a conflict of interest in providing patient care.

Although no improvements in patient outcomes were found, this study has demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of a collaborative relationship between family physicians and local, specially trained pharmacists.

β See related article page 30

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the family physicians, pharmacists and the senior citizens who participated in this study. We thank Lesley Lavack, Assistant Dean, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, for her assistance with recruiting and training the pharmacists. We also thank Dr. Stuart MacLeod for his expertise in assessing hospital admissions and for overall support of the project.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the North American Primary Care Research Group Conference, Amelia Island, Fla., 2000; the Canadian Association for Population Therapeutics, Montréal, Que., 2000; and the Canadian Association for Population Therapeutics, Banff, Alta., 2001.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Drs. J. Sellors, Kaczorowski, Dolovich, Woodward, Willan, Sebaldt and Poston and Ms. C. Sellors and Mr. Goeree contributed to the study design. Drs. J. Sellors, Kaczorowski, Dolovich, Woodward, Willan, Sebaldt and Poston and Ms. C. Sellors, Mr. Goeree, Ms. Cosby, Ms. Trim and Ms. Hardcastle contributed to the data acquisition. Dr. Willan conducted the data analysis and Ms. Howard contributed to it. Drs. J. Sellors and Kaczorowski wrote the manuscript. Drs. Kaczorowski, Woodward, Dolovich, Willan, Sebaldt and Poston and Ms. C. Sellors, Mr. Goeree, Ms. Cosby, Ms. Trim, Ms. Howard and Ms. Hardcastle critically revised the manuscript. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the results and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Funding was provided by the Health Transition Fund, Health Canada, and in-kind support from the Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University, and the Centre for Evaluation of Medicines, St. Joseph's Healthcare, Hamilton, Ont.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Janusz Kaczorowski, Department of Family Medicine, McMaster University, 1200 Main St. West, HSC-2V11, Hamilton ON L8N 3Z5; fax 905-521-5594; kaczorow@mcmaster.ca

References

- 1.Stewart RB. Polypharmacy in the elderly: a fait accompli? DICP: the annals of pharmacotherapy 1990;24:321-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Tamblyn RM, McLeod PJ, Abrahamowicz M, Monette J, Gayton DC, Berkson L, et al. Questionable prescribing for elderly patients in Quebec. CMAJ 1994;150:1801-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Avorn J. Medication use and the elderly: current status and opportunities. Health Aff 1995;14:276-86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Col N, Fanale JE, Konholm P. The role of medication noncompliance and adverse drug reactions in hospitalizations of the elderly. Arch Intern Med 1990; 150:841-5. [PubMed]

- 5.Bero LA, Lipton HL, Bird JA. Characterization of geriatric drug-related hospital readmissions. Med Care 1991;29:989-1003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Einarson TR. Drug-related hospital admissions. Ann Pharmacother 1993; 27: 832-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Lindley CM, Tully MP, Paramsothy V, Tallis RC. Inappropriate medication is a major cause of adverse drug reactions in elderly patients. Age Ageing 1992;21:294-300. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Schmader K, Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Landsman PB, Samsa GP, Lewis IK, et al. Appropriateness of medication prescribing in ambulatory elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42:1241-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Willcox SM, Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S. Inappropriate drug prescribing for the community-dwelling elderly. JAMA 1994;272:292-6. [PubMed]

- 10.Hogan DB, Ebly EM, Fung TS. Regional variations in use of potentially inappropriate medications by Canadian seniors participating in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Can J Clin Pharmacol 1995;2:167-74.

- 11.Tamblyn RM, McLeod PJ, Abrahamowicz M, Laprise R. Do too many cooks spoil the broth? Multiple physician involvement in medical management of elderly patients and potentially inappropriate drug combinations. CMAJ 1996; 154:1177-84. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Zhan C, Sangl J, Bierman AS, Miller MR, Friedman B, Wickizer SW, et al. Potentially inappropriate medication use in the community-dwelling elderly: findings from the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. JAMA 2001; 286: 2823-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Aparasu RR, Mort JR. Inappropriate prescribing for the elderly: Beers criteria-based review. Ann Pharmacother 2000;34:338-46. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Sidel VW, Beizer JL, Lisi-Fazio D, Kleinmann K, Wenston J, Thomas C, et al. Controlled study of the impact of educational home visits by pharmacists to high-risk older patients. J Community Health 1990;15:163-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Rupp MT, DeYoung M, Schondelmeyer SW. Prescribing problems and pharmacist interventions in community practice. Med Care 1992;30:926-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.McMullin ST, Hennenfent JA, Ritchie DJ, Huey WY, Lonergan TP, Schaiff RA, et al. A prospective, randomized trial to assess the cost impact of pharmacist-initiated interventions. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2306-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Lipton HL, Bero LA, Bird JA, McPhee S. The impact of clinical pharmacists' consultation on physician's geriatric drug prescribing. A randomized controlled trial. Med Care 1992;30:646-58. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, Schmader KE, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med 1996;100:428-37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Jameson J, VanNoord G, Vanderwoud K. The impact of a pharmacotherapy consultation on the cost and outcome of medical therapy. J Fam Pract 1995; 41: 469-72. [PubMed]

- 20.Bernsten C, Björkman I, Caramona M, Crealey G, Frøkjær B, Grundberger E, et al. Improving the well-being of elderly patients via community pharmacy-based provision of pharmaceutical care. A multicentre study in seven European countries. Drugs Aging 2001;18:63-77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Krska J, Cromarty JA, Arris F, Jamieson D, Hansford D, Duffus PR, et al. Pharmacist-led medication review in patients over 65: a randomized controlled trial in primary care. Age Ageing 2001;30:205-11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Volume CI, Farris KB, Kassam R, Cox CE, Cave A. Pharmaceutical care research and education project: patient outcomes. J Am Pharm Assoc 2001; 41: 411-20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sellors J, Cosby R, Trim K, Kaczorowski J, Howard M, Hardcastle L, et al. Recruiting family physicians and patients for a clinical trial: lessons learned. Fam Pract 2002;19:99-104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hepler CD, Strand LM. Opportunities and responsibilities in pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm 1990;47:533-43. [PubMed]

- 25.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Wonder. International classification of diseases. Available: http://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/cgi-bin/asp/ICDFinder.asp (accessed 1999 Nov to 2000 Mar).

- 26.Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, Ramsey R, Landsman GD. Drug-related problems: their structure and function. DICP: the annals of pharmacotherapy 1990;24:1093-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Sellors C, Dalby DM, Howard M, Kaczorowski J, Sellors J. A pharmacist consultation service in community-based family practices: a randomized controlled trial in seniors. J Pharm Technol 2001;17:264-9.

- 28.McHorney C, Ware JJ, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item Short-Form health survey (SF-36):II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs_. Med Care_ 1993;31:247-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Cosby RH, Howard M, Kaczorowski J, Willan A, Sellors JW. Randomizing patients by family practice: sample size estimation, intracluster correlation, and data analysis. Fam Pract 2003;20(1):77-82. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Thompson SG, Pyke SD, Hardy RJ. The design and analysis of paired cluster randomization trials: an application of meta-analysis techniques. Stat Med 1997;16:2063-79. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Canadian Medical Association–Canadian Pharmaceutical Association Joint Statement. Approaches to enhancing the quality of drug therapy. CMAJ 1996; 155(6):784A-F. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Beney J, Bero LA, Bond C. Expanding the roles of outpatient pharmacists: effects on health services utilization, costs, and patient outcomes. [Cochrane review]. In: The Cochrane Library; Issue 4, 2002. Oxford: Update Software. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Avorn J, Soumerai SB. Improving drug-therapy decisions through educational outreach. A randomized controlled trial of academically based “detailing”. N Engl J Med 1983;308:1457-63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Morse GD, Douglas JB, Upton JH, Rodgers S, Gal P. Effect of pharmacist intervention on control of resistant hypertension. Am J Hosp Pharm 1986; 43: 905-9. [PubMed]

- 35.Bogden PE, Abbott RD, Williamson P, Onopa JK, Koontz LM. Comparing standard care with a physician and pharmacist team approach for uncontrolled hypertension. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:740-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Bogden PE, Koontz LM, Williamson P, Abbott RD. The physician and pharmacist team: an effective approach to cholesterol reduction. J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:158-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Tsuyuki RT, Johnson JA, Toe KT, Simpson SH, Ackman ML, Biggs RS, et al. A randomized trial of the effect of community pharmacist intervention on cholesterol risk management. Arch Int Med 2002;162:1149-55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Ellis SL, Billups SJ, Malone DC, Carter BL, Covey D, Mason B, et al. Types of interventions made by clinical pharmacists in the IMPROVE study. Pharmacotherapy 2000;20:429-35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Jaber LA, Halapy H, Fernet M, Tummalapalli S, Diwakaran H. Evaluation of a pharmaceutical care model on diabetes management. Ann Pharmacother 1996; 30:294-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Weinberger M, Murray MD, Marrero DG, Brewer N, Lykens M, Harris LE, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacist care for patients with reactive airways disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288:1594-602. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Grymonpre RE, Williamson DA, Montgomery PR. Impact of a pharmaceutical care model for non-institutionalised elderly: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Int J Pharm Pract 2001;9:235-41.

- 42.Allard J, Hébert R, Rioux M, Asselin J, Voyer L. Efficacy of a clinical medication review on the number of potentially inappropriate prescriptions prescribed for community-dwelling elderly people. CMAJ 2001;164:1291-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Stadnyk K, Calder J, Rockwood K. Testing the measurement properties of the Short Form-36 health survey in a frail elderly population. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:827-35. [DOI] [PubMed]