Characterization of the Host Proinflammatory Response to Tumor Cells during the Initial Stages of Liver Metastasis (original) (raw)

Abstract

The influx of metastatic tumor cells into the liver triggers a rapid proinflammatory cytokine cascade. To further analyze this host response, we used intrasplenic/portal inoculation of green fluorescent protein-marked human and murine carcinoma cells and a combination of immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy. The metastatic murine lung carcinoma H-59 or human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 cells triggered tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production by Kupffer cells located in sinusoidal vessels around the invading tumor cells. H-59 cells rapidly elicited a fourfold increase in the number of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells relative to basal levels within 2 hours and this response declined gradually after 6 hours. Increased cytokine production in these mice was confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay performed on isolated Kupffer cells. CX-1 cells elicited a more gradual response that peaked at 10 to 16 hours, remained high up to 48 hours, and involved CX-1-Kupffer cell attachment. Furthermore, the rapidly induced production of TNF-α was followed by increased expression of the vascular adhesion receptors E-selectin P-selectin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on sinusoidal endothelial cells. This proinflammatory response was tumor-specific and was not observed with nonmetastatic murine M-27 or human MIP-101 carcinoma cells. These results identify Kupffer cell-mediated TNF-α production as an early, tumor-selective host inflammatory response to liver-invading tumor cells that may influence the course of metastasis.

The liver is a major site of metastases for some of the most common human malignancies, carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract in particular. Liver metastases are frequently inoperable and are associated with poor prognosis.1 The metastatic cascade involves a sequence of steps that can lead to tumor cell arrest in the vascular bed of an invaded organ such as the liver and subsequently to tumor extravasation into the extravascular space.2 These events are regulated by, and in turn, can induce host proinflammatory responses that involve tumor- and host-derived chemokines and cytokines. A key mediator of the inflammatory response is tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. This cytokine can play a dual role in tumor progression and metastasis. On one hand it can inhibit tumor growth through its cytocidal and proapoptotic activities but on the other, it can promote tumor progression through different mechanisms such as the induction of vascular endothelial adhesion receptors and the promotion of growth, invasion, and metastasis. The ultimate effect of TNF-α may depend on its concentrations, on tumor cell susceptibility, and on the stage of the disease.3,4 TNF-α-inducible cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) on the luminal surface of the microvascular endothelium are thought to mediate tumor-endothelial cell adhesion and thereby facilitate tumor cell arrest and transmigration into the extravascular space.2 Among the vascular endothelial cell receptors that have been implicated in cell-cell adhesion and transendothelial migration are P-, E-, and L-selectin5 and vascular adhesion receptors of the immunoglobulin superfamily such as intercellular adhesion molecules ICAM-1, -2, and -3, vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, and mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule (MadCAM)-1.5,6 In general, the selectins bind sialylated, glycosylated, or sulfated glycans on glycoproteins, glycolipids, or proteoglycans.5 The tetrasaccharides sialyl-Lewisx (sLewx) and sialyl-Lewisa (sLewa) are recognized by all three selectins and have been identified as markers of progression in carcinomas of the gastrointestinal tract that commonly metastasize to the liver.7 These molecules are thought to mediate tumor cell adhesion to the hepatic microvascular endothelial cells during liver metastasis.8–11 Under normal physiological conditions, vascular endothelial cells express low constitutive levels of E-selectin. The induction of E-selectin can be mediated by several cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-1α and TNF-α5,12 through activation of the Raf/MEK/MAPK pathway and nuclear factor-κB.12,13

We previously used live- metastasizing human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 and murine lung carcinoma subline H-59 cells to investigate the host inflammatory response elicited by tumor cells during the early stages of liver colonization. We found that the intrasplenic/portal inoculation of these, but not of the nonmetastatic human MIP-101 and murine M-27 cells, rapidly increased TNF-α and IL-1α production in the liver leading in turn, to rapid induction of vascular endothelial E-selectin and liver metastasis.12,14,15 Inhibition of E-selectin induction or function resulted in blockade of metastasis.12,14 The objectives of the present study were to further analyze the host proinflammatory response triggered by invading tumor cells and the role of the hepatic Kupffer cells in this response.

Materials and Methods

Cells

The tumor cells used in this study were the murine Lewis lung carcinoma sublines H-59 (highly metastatic to liver) and M-27 (poorly metastatic), the B16-F1 melanoma cells (a kind gift from Dr. A. Chambers, The London Regional Cancer Center, London, Ontario, Canada), the human colorectal carcinoma lines CX-1 (highly metastatic) and MIP-101 (nonmetastatic) (a kind gift from Dr. Peter Thomas, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA). The macrophage cell line ANA-1 was derived from the bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice and previously characterized in detail.16 All of the cells were maintained in RPMI medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 300 μg/ml glutamine. Routine testing confirmed that the cells were free of mycoplasma and viral contaminants during the study period. M-27GFP and MIP-101GFP cells were generated by transfection of the parental cells with 1 to 5 μg of the pLEGFP-N1 plasmid (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) using Lipofectamine Plus as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transfectants were selected using 100 μg/ml G-418 (Invitrogen) and maintained in complete RPMI medium containing the same concentration of G-418. They were used in this study without further cloning. The H-59 and CX-1 cells were transduced with the vLTR-GFP retrovirus at an multiplicity of infection of 15 and 10, respectively, as we previously described.17 H-59GFP cells were used without further selection. Highly fluorescent CX-1GFP cells were obtained by sorting the top 30% of fluorescent cells using a fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS-Vantage flow cytometer/cell sorter; Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA).18

Antibodies

The polyclonal rabbit antibodies to murine IL-1α and TNF-α were from Genzyme (Cambridge, MA) and from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), respectively. Rat monoclonal antibody to murine F4/80 was from Cedarlane Laboratories (Hornby, Ontario, Canada) and rat monoclonal antibodies to murine E-selectin and VCAM-1 were from Pharmingen (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-goat or goat anti-rat antibodies and Alexa Fluor 350 goat anti-rat antibodies were from Molecular Probes Inc. (Eugene, Oregon).

Intrasplenic/Portal Injections

C57BL/6 female mice (6 to 12 weeks old, obtained from Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were anesthetized by an intramuscular injection of 0.5 mg/kg acepromazine followed 10 to 25 minutes later by an intramuscular injection of ketamine/xylazine at final concentrations of 100 and 10 mg/kg, respectively. The spleens were exposed through a small abdominal incision, 106 tumor cells in 0.1 ml of saline, or saline alone, were inoculated, and the animals splenectomized 1 minute later. The livers were removed and either used immediately for Kupffer cell isolation or snap-frozen in liquid N2 and then stored at −80°C until they were analyzed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). In several control experiments, Swiss NIH Nu/Nu, female mice (6 to 8 weeks old; Taconic Laboratories, Germantown, NY) were also used to inject human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 or MIP-101 cells.12

Immunohistochemistry and Confocal Microscopy

After tumor cell injection, the livers were perfused with 50 ml of a 4% paraformaldehyde solution, fixed for 48 hours in the same fixative, transferred into a 30% sucrose solution for 4 days, and placed in OTC medium before freezing at −80°C. Immunohistochemistry was performed on 7-μm cryostat sections. For TNF-α and F4/80 co-labeling, the sections were incubated first in a blocking solution [1% donkey serum, 1% goat serum, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for 30 minutes and then overnight at 4°C with the primary antibodies (5 μg/ml goat anti-mouse TNF-α and a 1:100 dilution of rat anti-murine F4/80). After several washes with PBS, the sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-goat IgG antibody (1:200 dilution in blocking buffer) and then, after extensive washes in PBS, with Alexa Fluor 350 goat anti-rat IgG antibody (1/200 dilution in blocking buffer). All sections were mounted in Prolong Gold anti-fade reagent (Molecular Probes). To quantify TNF-α+ Kupffer cells, five digitized images in which tumor cells were clearly visible were acquired per liver section using a Zeiss microscope and a total of four representative sections derived from four different livers (a total of 20 images) were analyzed per time point (reproducibility of data among different sections from the same livers was confirmed in preliminary experiments). TNF-α+ Kupffer cells in each image were counted manually and a percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells per liver section was calculated. For E-selectin or VCAM-1 immunostaining, the same protocol was used, primary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:50 and the Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rat antibody was used at a dilution of 1:200.

Isolation and Culture of Murine Kupffer Cells

H-59 cells or saline were injected into syngeneic mice by the intrasplenic/portal route, the livers were removed at different time intervals thereafter and Kupffer cells isolated by collagenase perfusion and metrizamide gradient centrifugation as described previously.19 Kupffer cell viability was greater than 95% as determined by trypan blue exclusion dye and their purity exceeded 90% as determined by mAb F4/80 staining. The cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture dishes, cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 90% air and 10% CO2, and used within 3 to 4 hours as required.

Measurement of TNF-α and IL-1α Production by Kupffer Cells Using Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

Kupffer cells were isolated 2 hours after the intrasplenic/portal inoculation of H-59 cells, plated in 24-well plates, and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. They were then lysed in 50 mmol/L Tris buffer, pH 7.5, containing 0.15 mol/L NaCl, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 1 mmol/L EGTA, 2 mmol/L dithiothreitol, and 25 μg/ml leupeptin and aprotinin and analyzed for the presence of IL-1α and TNF-α using the cytokine ELISA kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Genzyme). Cytokine concentrations were calculated from a standard curve.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from snap-frozen livers or cultured cells using the TRIzol reagent (Gibco BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada). Two μg of total RNA were reverse-transcribed using a reaction mixture containing 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 30 mmol/L KCl, 8 mmol/L MgCl2, 10 mmol/L dithiothreitol, 100 ng oligo(dt)12-18, 40 U RNase inhibitor, 1 mmol/L deoxy-NTPs, and 8 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (all from Pharmacia Biotech, Baie D’Urfe, Quebec, Canada). The mixture was incubated for 10 minutes at 25°C, then for 45 minutes at 42°C and finally for 5 minutes at 95°C. The upstream and downstream primers used were as follows: for P-selectin: 5′-TTGACGTACCAGTCAGTCTG-3′ and 5′-GTCACTGCTGTCCATTGTC-3′; for VCAM-1: 5′-CTCTGTACATCCCTCCACA-3′ and 5′-GGGACTGTGCAGTTGACAG-3′; for ICAM-1: 5′-AGCTAGCGGACCAGATCC-3′ and 5′-ATACAGCACGTGCAGTTCC-3′ and for PECAM: 5′-AGCTAGCGGACCAGATCC-3′ and 5′-ATACAGCACGTGCAGTT-3′ and 5′-TATGAAAGCAAAGAG-TGA-3′ and 5′-CGCAATCCAGGAATCGGCTGCTCTTC-3′. The primers for TNF-α, IL-1α, and GAPDH were previously described.15 The cDNA amplification was performed using previously established conditions.12

Activation of Cultured Macrophages by Tumor Cell-Derived Factors

Serum-free conditioned media were harvested from 24-hour cultures of the tumor cells. The media were filtered to ensure that they were cell-free and sterile and added without further concentration to ANA-1 cells (a kind gift from Dr. Danuta Radzioch, Department of Medicine, McGill University Health Center) that were preseeded 24 hours earlier in six-well plates, at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. The cultures were then incubated for 8 hours at 37°C, the ANA-1 cell supernatants harvested, and TNF-α levels analyzed by ELISA using the protocol described in detail elsewhere.20 ANA-1 cells incubated for the same duration with 100 ng/ml of lipopolysaccharide were used as positive controls.

Results

Increased Kupffer Cell-Associated TNF-α Production in Response to Metastatic Tumor Cells

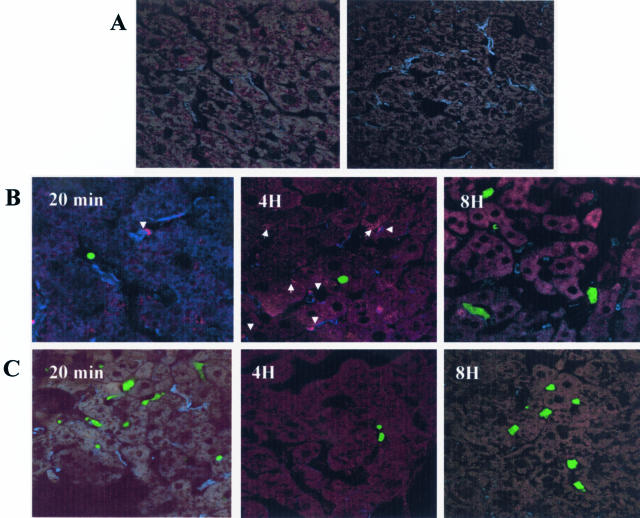

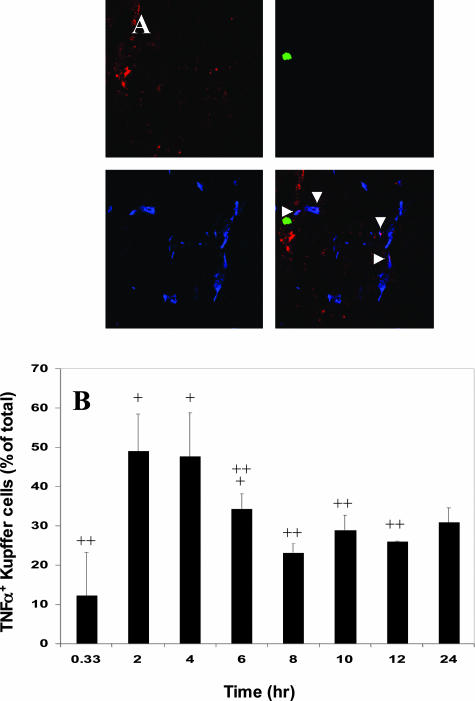

We have shown that tumor cell entry into the liver can trigger a proinflammatory response involving increased TNF-α production. To further investigate the course of the inflammatory response elicited by the tumor cells and determine the role of Kupffer cells in this response, immunohistochemistry and confocal microscopy were used. Liver cryostat sections were obtained from animals injected with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-expressing H-59 or M-27 cells at different time points after the intrasplenic/portal injection of 1 × 106 cells and the sections were immunostained with antibodies to TNF-α and to the macrophage-specific marker F4/80. The Kupffer cells were selected for detailed analysis because they are known to play a central role in the host hepatic response to various inflammatory triggers.21,22 Antibodies to F4/80 identified Kupffer cells within sinusoidal vessels in sections derived from tumor or saline-injected mice. Staining for TNF-α in control, saline-injected mice was either negative or low (Figure 1A). TNF-α levels increased gradually in response to the injection of H-59 cells but no increase in TNF-α signal was seen in response to nonmetastatic M-27 cells (Figure 1B). This increase in TNF-α production was Kupffer cell-associated and could not be detected in association with either neutrophils or platelets stained with antibodies to their respective cell surface markers (not shown). Kupffer cell-associated TNF-α staining in sinusoidal vessels surrounding the infiltrating tumor cells began to rise above baseline levels (12%) 2 hours after the injection of H-59 cells, reaching 50% of all of the Kupffer cells observed in proximity to the tumor cells. The response began to decline by 6 hours, and the levels were not significantly different from baseline TNF-α production levels by 8 hours after tumor injection (Figure 2). Interestingly, in mice with high levels of TNF-α-positive Kupffer cells, TNF-α signal was found in association with the hepatocytes (Figure 1B; 4H, arrow) suggesting that soluble TNF-α may bind to the hepatic parenchymal cells through their cell surface TNF receptors.23–25

Figure 1.

Rapid increase in TNF-α production in response to metastatic H-59 cells. Cryostat sections (7 μm) were prepared from livers removed at different time points after the inoculation of 106 H-59 (B) or M-27 (C) cells. Sections were double stained with a macrophage-specific mAb F4/80 and anti-TNF-α antibody. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 350 (blue) and Alexa Fluor 568 (red), respectively. The tumor cells express GFP and are shown in green. Arrowheads show co-localization of TNF-α and Kupffer cells and arrows show hepatocytes with positive TNF-α staining. A: A representative control section derived from mice injected with saline only and stained with anti TNF-α and anti F4/80 antibodies (left) and a section in which the anti-TNF-α antibody was omitted (right). Original magnifications, ×630.

Figure 2.

Increased Kupffer cell-mediated TNF-α production in response to H-59 cells is rapid and short lived. Cryostat sections (7 μm) were prepared from livers removed at the time intervals indicated after H-59 injection and stained with the macrophage-specific mAb F4/80 and an anti-TNF-α antibody. Secondary antibodies were Alexa Fluor 350 (blue) and Alexa Fluor 568 (red), respectively. A: Representative images showing Kupffer cells (blue), TNF-α (red), H-59 (green), and the merged confocal images. Arrowheads show co-localization of TNF-α and the Kupffer cell marker. B: The percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells in vessels surrounding the tumor cells at different time points after tumor inoculation was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. +P < 0.05 as compared to percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells at 20 minutes. ++P < 0.05 as compared to percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells at 2 hours. Original magnifications, ×630.

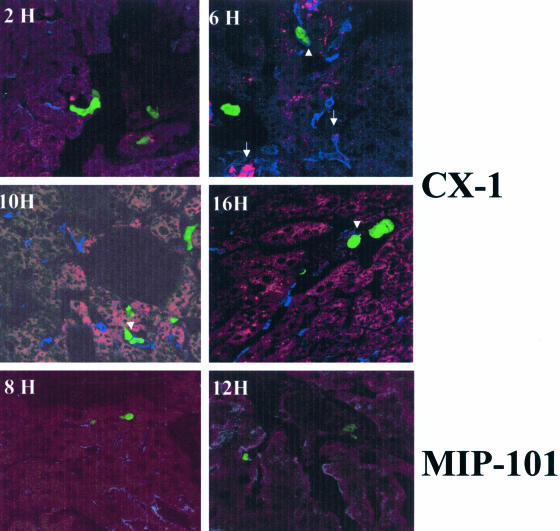

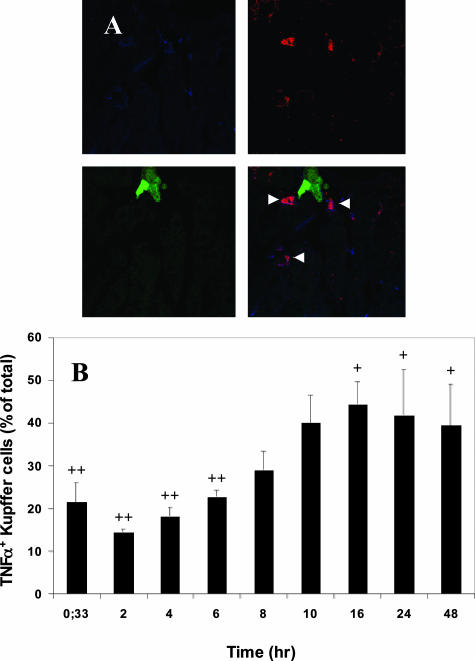

Activation of Kupffer cell-associated TNF-α production was also observed after the injection of highly metastatic human colorectal carcinoma CX-1, but not poorly metastatic MIP-101 cells (Figure 3). The response elicited by CX-1 cells was however, distinct from that generated by H-59 cells. Kupffer cell-associated TNF-α production rose gradually after CX-1 injection, reaching peak levels only at 10 to 16 hours, at a time when the H-59-induced response was already in decline. In addition, TNF-α production did not decline as rapidly, remaining high for up to 48 hours after tumor injection, in accordance with our previous observations based on RT and real-time PCR (Figure 4).12 Interestingly, in livers of animals inoculated with CX-1, but not with H-59 cells, tumor-Kupffer cell clusters were observed as early as 2 hours after tumor inoculation coinciding with the rise in TNF-α production by the Kupffer cells (Figure 3, arrowhead). MIP-101-Kupffer cell clusters were not observed at any of the time points analyzed. The tumor-selective induction of TNF-α expression was not due to differences in the number of tumor cells that could reach the liver after the intrasplenic/portal inoculation. This was revealed by quantifying GFP+ tumor cells in the liver 20 minutes after tumor cell injection. The numbers of tumor cells/field detectable after the injection of H-59 and M-27 cells were 45 ± 5.5 and 48 ± 10, respectively (n = 30, P = 0.63), whereas the numbers detectable after the injection of CX-1 and MIP-101 cells were 29 ± 4.8 and 23 ± 8, respectively (n = 30, P = 0.12), suggesting that the number of cells that reached the liver per se was not a major factor in determining the host reactivity.

Figure 3.

Increased TNF-α production in response to the metastatic human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 cells. Cryostat sections were prepared from livers removed at different time intervals after the inoculation of 106 CX-1 or MIP-101 cells. Immunostaining was as described in detail in the legend to Figure 2. Arrowheads show CX-1-Kupffer cell conjugates. Arrowsshow co-localization of TNF-α and Kupffer cells. Control sections labeled with the secondary antibody alone were negative. Original magnifications, ×630.

Figure 4.

Delayed onset and sustained Kupffer cell-mediated TNF-α production in response to CX-1 cells. Sections were prepared and labeled as described in the legend to Figure 2. A: Representative images showing Kupffer cells (blue), TNF-α (red), CX-1 cells (green), and the merged confocal image. Arrowheads show co-localization of TNF-α and Kupffer cells. B: The percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells at different time intervals after tumor injection was calculated as for Figure 2. +P < 0.05 as compared to 20 minutes. ++P < 0.05 as compared to percentage of TNF-α+ Kupffer cells at 16 hours. Original magnifications, ×630.

Increased Cytokine Levels in Kupffer Cells Isolated from Tumor-Inoculated Mice

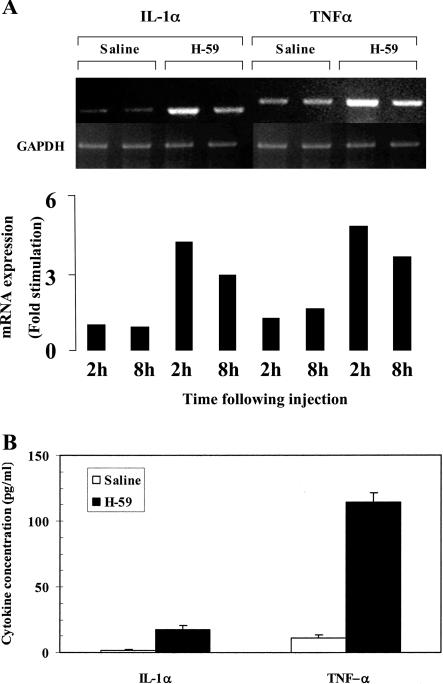

Increased cytokine production by Kupffer cells in response to tumor injection was confirmed in vitro by RT-PCR and ELISA performed on Kupffer cells that were isolated 2 and 8 hours after the injection of H-59 cells. Results in Figure 5A show that in cells obtained from saline-injected mice, low baseline levels of TNF-α and IL-1α mRNA were detectable. These levels were increased by 4.8-fold (TNF-α) and 4.5-fold (IL-1α) in Kupffer cells harvested 2 hours after H-59 injection and remained elevated (2.9- and 3.6-fold, respectively) in Kupffer cells isolated 8 hours after injection. The increases in cytokine mRNA levels were reflected in increased protein production as determined by ELISA. Results shown in Figure 5B indicate that the low basal levels of TNF-α and IL-1α detectable in control Kupffer cells derived from saline-injected mice were increased by 10- and 12-fold, respectively, in Kupffer cells isolated 2 hours after tumor injection. The level of TNF-α produced by isolated Kupffer cells after saline or tumor cells injection was fourfold higher than the level of IL-1α.

Figure 5.

Increased cytokine production by Kupffer cells isolated from tumor-inoculated mice. Animals were injected via the intrasplenic/portal route with 106 H-59 cells and their livers removed at 2 (A, B) and 8 (A) hours. A: For RNA extraction the cells were cultured for 4 hours and total RNA was analyzed by RT-PCR. A: Results of laser densitometry performed on the cDNA bands. They are expressed as cytokine/GAPDH density ratios. B: For protein analysis the cells were cultured in 24-well plates for 24 hours, lysed, and cytokine levels in the cell lysates measured by ELISA. Shown in B are cytokine concentrations in the cell lysates as calculated based on a standard curve.

Up-Regulated Expression of Vascular Adhesion Molecules in Response to Tumor Cells

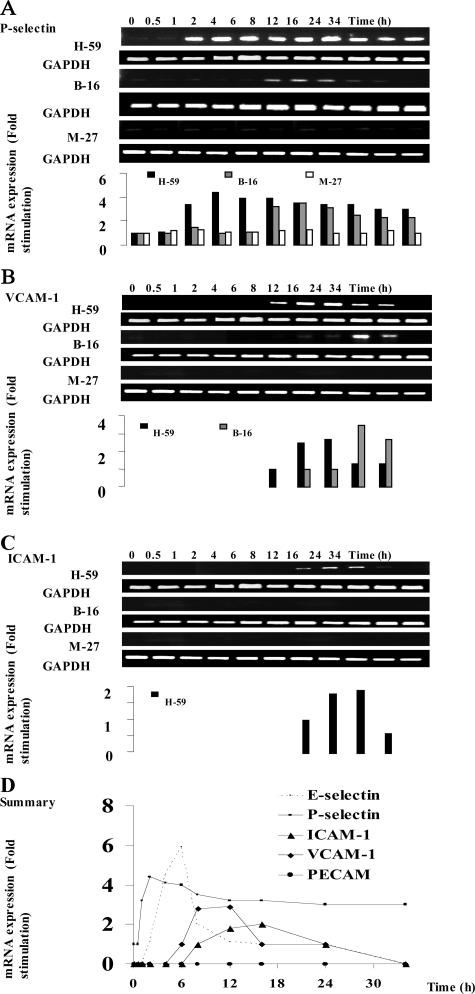

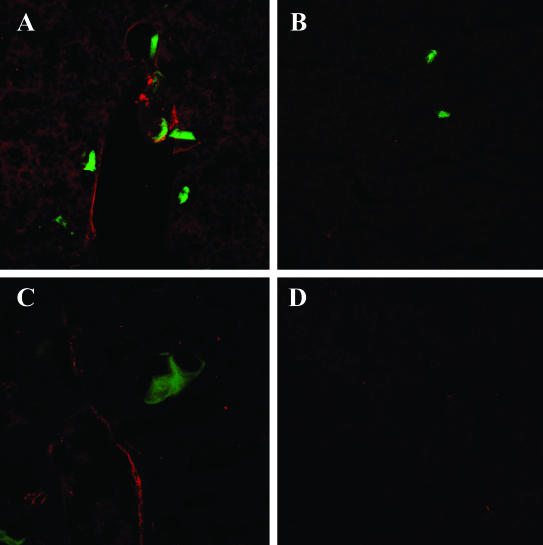

We previously reported that the increased expression of hepatic TNF-α in response to tumor cells was followed by an up-regulated expression of E-selectin on sinusoidal vessels (Figure 6D).15 To investigate whether the expression of other vascular adhesion receptors that have been implicated in transendothelial migration was also affected, the livers were removed at different time intervals after inoculation of H-59 cells, and P-selectin, VCAM-1, and ICAM-1 mRNA levels were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Low constitutive levels of P-selectin mRNA were detectable in livers obtained from control, noninjected, or saline-injected animals. H-59 inoculation caused a rapid (1 hour) and long-lasting induction of P-selectin mRNA (up to 34 hours) whereas the injection of M-27 cells did not alter basal P-selectin mRNA levels at any of the time intervals examined (Figure 6A). A third murine cell line used in these experiments, namely the weakly metastatic B16 F1 cells elicited a delayed and more transient P-selectin induction that was evident only at 4 to 6 hours after injection and declined after 16 to 24 hours. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA expression were analyzed in a similar manner. In livers derived from noninjected or saline-injected mice, mRNA expression was low. The injection of H-59 cells caused a slow but sustained increase in ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA levels. These levels began to rise within 6 to 8 hours, were maximal at 12 hours, and returned to basal levels by 24 hours after tumor injection (Figure 6, B and C). The injection of B16-F1 cells induced only a weak VCAM-1 signal that was detectable at 6 to 8 hours increasing for up to 16 hours and declining by 24 hours whereas the injection of M-27 cells failed to alter ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 mRNA levels at any of the time intervals investigated (Figure 6, B and C). None of the tumor cells injected were able to induce PECAM-1 mRNA expression (Figure 6D). The time course for CAM mRNA induction as observed after the inoculation of H-59 cells is summarized in Figure 6D. The selective induction of vascular adhesion molecules by H-59 and M-27 cells was also confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Intense positive staining for E-selectin on the hepatic vessels was seen at 6 to 8 hours after tumor cell injection while VCAM-1 staining was first detectable at 6 to 8 hours and persisted for up to 24 hours after H-59 injection. In livers of mice injected with M-27 cells, only weak E-selectin staining was occasionally seen and no VCAM-1 staining was observed between 6 and 24 hours after tumor injection. Representative immunohistochemistry results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

Induction of multiple hepatic vascular cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) after tumor cell inoculation. Syngeneic C57BL/6 mice were injected with 106 H-59, B-16, or M-27 cells by the intrasplenic/portal route, and their livers were removed at the time intervals indicated. Total RNA was extracted and analyzed by RT-PCR using specific primers for the murine CAMs indicated or for GAPDH. Results of laser densitometry are shown in the graph and are expressed as the ratio of CAM/GAPDH signal relative to the control (livers of noninjected mice), which was assigned a value of 1. Shown are results for P-selectin (A), VCAM-1 (B), and ICAM (C) and a summary of our findings based on the time course of CAM induction after inoculation of H-59 cells (D). Included in D are the present results (P-selectin, VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and PECAM) and previously published data (E-selectin).15

Figure 7.

Increased expression of E-selectin and VCAM-1 on hepatic vascular endothelial cells after tumor cell inoculation. Cryostat sections (7 μm) were prepared from livers removed at 8 (A, B) or 12 (C, D) hours after the inoculation of 106 H-59 (A, C) or M-27 (B, D) cells. The sections were stained with antibodies to E-selectin (A, B) or VCAM-1 (C, D) and with Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-rat antibodies. The tumor cells express GFP and are shown in green.

Metastatic Tumor Cells Produce Soluble Factors that Can Activate TNF-α Production in Cultured Macrophages

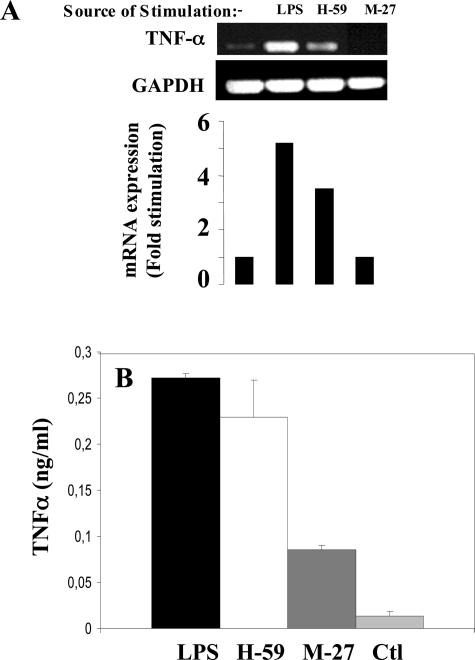

To further investigate the tumor-induced activation of cytokine production in macrophages, an in vitro model was used. Murine macrophage ANA-1 cells grown in serum-depleted medium were incubated for 2 hours with serum-free media conditioned by H-59 or M-27 cells. TNF-α production by the macrophages was then analyzed by RT-PCR. Results in Figure 8A show that in ANA-1 cells incubated with serum-free medium, low basal levels of TNF-α mRNA were detectable. These levels increased by 3.5-fold in response to treatment with H-59-conditioned media, but were unchanged in response to M-27-conditioned media. As a comparison, lipopolysaccharide (a positive control) increased TNF-α mRNA production in ANA-1 cells by 5.5-fold. The increased production of TNF-α was also confirmed by an ELISA performed on ANA-1 supernatants 8 hours after the addition of tumor-conditioned medium as shown in Figure 8B. Basal TNF-α levels detectable in H-59- and M-27-conditioned media were low (0.0205 ng/ml and 0.0214 ng/ml, respectively) and comparable to those detected in control, nonstimulated ANA-1 cells (0.0205 ng/ml).

Figure 8.

Metastatic tumor cells produce soluble factors that can activate TNF-α production in cultured macrophages. Murine macrophage ANA-1 cells grown in serum-depleted medium for 24 hours were incubated for 2 hours (A) or 8 hours (B) with serum-free media conditioned by the indicated tumor cells. Shown in A are results of a RT-PCR analysis performed on RNA extracted from the ANA-1 cells. Results of laser densitometry are shown in the bar graph and are expressed as the ratio of TNF-α:GAPDH signal, relative to the control. Shown in B are results of an ELISA performed on culture medium of ANA-1 cells incubated (or not) with tumor cell-conditioned media for 8 hours. Lipopolysaccharide-stimulated ANA-1 cells served as a positive control.

Discussion

The present study was prompted by our previous findings that the intrahepatic injection of metastatic tumor cells triggered a molecular cascade beginning with increased local production of cytokines TNF-α and IL-1α and culminating in up-regulated expression of E-selectin on the endothelium.12,15 The aims of this study were threefold: 1) to identify host cells involved in the proinflammatory response elicited by invading tumor cells; 2) to investigate spatial/temporal aspects of their activation relative to tumor entry into the liver; and 3) to identify other vascular adhesion molecules that may be up-regulated, in a selective manner, in response to metastatic tumor cells. Our results show that after the injection of the highly metastatic H-59 and CX-1 cells, hepatic Kupffer cells were rapidly activated to produce TNF-α and IL-1α. The intensity and duration of the response were variable, with the human colorectal carcinoma CX-1 cells eliciting a delayed but more intense and persistent response than murine H-59 cells12 and the poorly metastatic M-27 and MIP-101 cells failing to trigger a detectable response.

The factors that regulate these diverse host inflammatory responses to tumor cells are not presently known. However the proximity of the TNF-α-positive Kupffer cells to tumor-infiltrated vessels suggests that the tumor cells may produce soluble mediators that can activate resident hepatic macrophages. Indeed, our results have shown that medium conditioned by H-59, but not by M-27 cells could trigger TNF-α production by cultured, syngeneic murine macrophages, essentially mimicking the specificity observed in vivo and suggesting that the divergent ability of these tumors to induce a host inflammatory response is due, at least in part, to tumor-derived soluble factors. In the case of CX-1 cells, the tumor-Kupffer cell interaction also appeared to involve cell-cell contact. This is in agreement with previous reports based on in vitro studies that showed CX-1-Kupffer cell attachment.26 These studies also implicated tumor-derived carcinoembryonic antigen in the activation of cytokine expression in the Kupffer cells.27,28 It is conceivable that Kupffer cell activation by CX-1 cells is cell-cell contact-dependent and is therefore delayed relative to H-59 cells that do not appear to interact with the Kupffer cells directly. The ability of tumor cells to secrete macrophage-activating soluble factors or activate Kupffer cells through cell-cell contact could determine the nature of the hepatic host proinflammatory response and thereby regulate the arrest, localization, and fate of the metastasizing cells.29

Of interest is our observation that hepatocytes in livers of H-59-inoculated mice stained positively for TNF-α. The rapid uptake of TNF-α by these cells is consistent with other reports in which hepatocytes were identified as a target of Kupffer cell produced TNF-α in models of inflammation and liver regeneration.23–25,30 The long-term effect of TNF-α uptake on the hepatocytes and in turn, on the progression of metastasis in this model, are unknown. However hepatocytes have multiple cytoprotective mechanisms to counter TNF-α-induced cytotoxicity24 and major damage to hepatocytes has been shown to require a sustained exposure to TNF-α.25 Direct deleterious effects on the hepatocytes are therefore unlikely to occur as a consequence of the transient, short-term inflammatory response seen in this model.

Our results also show that tumor H-59 cells triggered a rapid increase in hepatic P-selectin mRNA levels. This was followed 6 to 8 hours later by increased expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. This response was tumor type-specific because it was either completely absent or delayed after the injection of nonmetastatic M-27 or B-16 F1 melanoma cells, respectively. This is in line with our previous observations that only the highly metastatic H-59 and CX-1, but not M-27 and MIP-101 cells could induce rapid expression of IL-1α, TNF-α, and E-selectin on entry into the hepatic microcirculation.12,15 P-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1 were also implicated in leukocyte adhesion to cytokine-activated endothelial cells during transendothelial migration5 with the selectins implicated in the characteristic rolling motion of leukocytes on the endothelial surface and ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 involved in high-affinity binding and leukocyte extravasation. It has been proposed that similar cell-cell interactions may also occur between circulating malignant cells expressing the appropriate ligands and the vascular endothelium during tumor dissemination.29,31,32

The role of the sinusoidal Kupffer cells during the early stages of hepatic metastasis has been the subject of conflicting results. The evidence suggests that these cells could play opposing roles and either inhibit or promote the growth of metastatic cells. In vitro studies provided compelling evidence that activated Kupffer cells play a role in tumor surveillance in the liver and can exert cytotoxic or cytostatic effects on various tumor cells including human colon adenocarcinoma cells.33 These tumoricidal effects could be induced by various mediators including cytokines.34,35 In one of these studies, the tumoricidal effect of Kupffer cells on colon adenocarcinoma MCA26 cells in vitro was in fact linked to their ability to produce IL-1α and TNF-α.34 On the other hand, our studies and others3,15 suggest that in vivo, cytokine production by activated Kupffer cells could actually accelerate liver metastases formation by inducing the expression of liver sinusoidal endothelial cell adhesion receptors, by promoting tumor cell migration and invasion, and by inducing an angiogenic response.36,37 Several factors may determine the ultimate outcome of Kupffer cell activation. In our own H-59 model, we have seen that preactivation of Kupffer cells by liposomal muramyl dipeptide before tumor injection could decrease liver metastases formation35 whereas the direct activation of the Kupffer cells by the tumor cells as seen in this and a previous study15 can lead to increased vascular endothelial cell CAM expression, which can ultimately increase metastasis. This suggests that the timing and level of activation relative to tumor cell entry into the liver microvasculature are crucial factors. Kupffer cells may exert tumoricidal effects if they are already highly activated at the time of first contact with the tumor cells but may promote extravasation and escape from host defenses if activation occurs only in response to, or in conjunction with, tumor cell infiltration. The ultimate effect of Kupffer cell activation on liver colonization by metastatic cells may also depend on the ability of the tumor cells to recognize cell adhesion receptors on the endothelium and rapidly exit the vascular lumen,9 on tumor cell ability to attach to the Kupffer cells,26–28 and on tumor cell susceptibility to Kupffer cell-derived cytotoxic factors such as TNF-α, interferon-γ, nitric oxide, and prostaglandin E2.38,39 In addition, carcinoembryonic antigen, an intercellular adhesion molecule was implicated in Kupffer cell activation that resulted in enhanced hepatic metastasis of colorectal carcinoma.40

The identification of Kupffer cell-derived TNF-α as a potential promoter of liver metastases raises questions regarding the utility of therapeutic strategies based on TNF-α treatment or the activation of a host inflammatory response. Our results and others3,4 suggest that a better understanding of the multiple factors that can determine the outcome of cytokine-based therapy is probably necessary before such treatments can be used successfully in the clinical prevention and management of hepatic and other metastases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Peter Thomas and Danuta Radzioch for gifts of cell lines and Mr. Thusanth Thuraisingam (Department of Medicine, McGill University) for his help with the TNF-α ELISA assay.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Pnina Brodt, Surgical Labs, Royal Victoria Hospital, Room H6.25, 687 Pine Ave., W. Montreal, Quebec, Canada H3A 1A1. E-mail: pnina.brodt@muhc.mcgill.ca.

Supported by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (grant MOP-13646 to P.B.).

A.-M.K., P.A., and L.F. contributed equally to this study.

Current address of A.-M.K.: Laboratoire de Pharmacologie Experimentale et Clinique, Institut National de la Sante et de la Recherche Médicale INSERM U716, Institut de Génétique Moleculaire, Paris, France.

References

- Cohen AM, Shank B, Friedman MA. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott,; 1989:pp 907–911. [Google Scholar]

- Pauli BU, Jonhson RC, Wildon J, Cheng CF. Endothelial cell adhesion molecules and their role in organ preference of metastasis. Trends Glycosci Glycotech. 1989;4:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson GM, Nakada MT, DeWitte M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the pathogenesis and treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo JL, Maeda S, Hsu LC, Yagita H, Karin M. Inhibition of NF-kappaB in cancer cells converts inflammation-induced tumor growth mediated by TNFalpha to TRAIL-mediated tumor regression. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlos TM, Harlan JM. Leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecules. Blood. 1994;84:2068–2101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Springer TA. Structural specializations of immunoglobulin superfamily members for adhesion to integrins and viruses. Immunol Rev. 1998;163:197–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamori S, Kameyama M, Imaoka S, Furukawa H, Ishikawa O, Sasaki Y, Kabuto T, Iwanaga T, Matsushita Y, Irimura T. Increased expression of sialyl Lewisx antigen correlates with poor survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma: clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3632–3637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexiou D, Karayiannakis AJ, Syrigos KN, Zbar A, Kremmyda A, Bramis I, Tsigris C. Serum levels of E-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 in colorectal cancer patients: correlations with clinicopathological features, patient survival and tumour surgery. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:2392–2397. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bresalier RS, Byrd JC, Brodt P, Ogata S, Itzkowitz SH, Yunker CK. Liver metastasis and adhesion to the sinusoidal endothelium by human colon cancer cells is related to mucin carbohydrate chain length. Int J Cancer. 1998;76:556–562. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980518)76:4<556::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laferriere J, Houle F, Huot J. Adhesion of HT-29 colon carcinoma cells to endothelial cells requires sequential events involving E-selectin and integrin beta4. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2004;21:257–264. doi: 10.1023/b:clin.0000037708.09420.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata K, Miyoshi E, Ihara S, Noura S, Kameyama M, Ishikawa O, Doki Y, Yamada T, Ohigashi H, Sasaki Y, Higashiyama M, Tarui T, Takada Y, Kannagi R, Taniguchi N, Imaoka S. Attachment of human colon cancer cells to vascular endothelium is enhanced by N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V. Oncology. 2004;66:492–501. doi: 10.1159/000079504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib AM, Fallavollita L, Wancewicz EV, Monia BP, Brodt P. Inhibition of hepatic endothelial E-selectin expression by C-raf antisense oligonucleotides blocks colorectal carcinoma liver metastasis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5393–5398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Moon SO, Kim SH, Kim HJ, Koh YS, Koh GY. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and E-selectin through nuclear factor-kappa B activation in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7614–7620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodt P, Fallavollita L, Bresalier RS, Meterissian S, Norton CR, Wolitzky BA. Liver endothelial E-selectin mediates carcinoma cell adhesion and promotes liver metastasis. Int J Cancer. 1997;71:612–619. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970516)71:4<612::aid-ijc17>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatib AM, Kontogiannea M, Fallavollita L, Jamison B, Meterissian S, Brodt P. Rapid induction of cytokine and E-selectin expression in the liver in response to metastatic tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1356–1361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox GW, Mathieson BJ, Gandino L, Blasi E, Radzioch D, Varesio L. Heterogeneity of hematopoietic cells immortalized by v-myc/v-raf recombinant retrovirus infection of bone marrow or fetal liver. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81:1492–1496. doi: 10.1093/jnci/81.19.1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani AA, Chevet E, Fallavollita L, Galipeau J, Brodt P. Loss of tumorigenicity and metastatic potential in carcinoma cells expressing the extracellular domain of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3380–3385. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani AA, Fallavollita L, Jaalouk DE, Galipeau J, Brodt P. Inhibition of carcinoma cell growth and metastasis by a vesicular stomatitis virus G-pseudotyped retrovector expressing type I insulin-like growth factor receptor antisense. Hum Gene Ther. 2001;12:1969–1977. doi: 10.1089/104303401753204544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meterissian S, Steele GD, Jr, Thomas P. Human and murine Kupffer cell function may be altered by both intrahepatic and intrasplenic tumor deposits. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1993;11:175–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00114975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin D, DeSanctis J, Boule M, Skamene E, Matouk C, Radzioch D. Role of tumor necrosis factor alpha in innate resistance to mouse pulmonary infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3272–3278. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3272-3278.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker K. The response of liver macrophages to inflammatory stimulation. Keio J Med. 1998;47:1–9. doi: 10.2302/kjm.47.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420:846–852. doi: 10.1038/nature01320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpes R, van den Oord JJ, De Vos R, Desmet VJ. Hepatic expression of type A and type B receptors for tumor necrosis factor. J Hepatol. 1992;14:361–369. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(92)90184-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sass G, Shembade ND, Tiegs G. Tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF)-TNF receptor 1 inducible cytoprotective proteins in the mouse liver: relevance of suppressors of cytokine signalling. Biochem J. 2005;385:537–544. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed FF, Smookler DS, Taylor SE, Fingleton B, Kassiri Z, Sanchez OH, English JL, Matrisian LM, Au B, Yeh WC, Khokha R. Abnormal TNF activity in Timp3−/− mice leads to chronic hepatic inflammation and failure of liver regeneration. Nat Genet. 2004;36:969–977. doi: 10.1038/ng1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meterissian SH, Toth CA, Steele G, Jr, Thomas P. Kupffer cell/tumor cell interactions and hepatic metastasis in colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 1994;81:5–12. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami S, Furui J, Kanematsu T. Role of carcinoembryonic antigen in the progression of colon cancer cells that express carbohydrate antigen. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2732–2735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P, Hayashi H, Zimmer R, Forse RA. Regulation of cytokine production in carcinoembryonic antigen stimulated Kupffer cells by beta-2 adrenergic receptors: implications for hepatic metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2004;209:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodt P. Adhesion receptors and proteolytic mechanisms in cancer invasion and metastasis. Heidelberg: Landes/Springer-Verlag,; 1996:pp 167–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura K, Nagaki M, Takai S, Satake S, Moriwaki H. Pivotal role of nuclear factor kappaB signaling in anti-CD40-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:1180–1189. doi: 10.1002/hep.20432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tozeren A, Kleinman HK, Grant DS, Morales D, Mercurio AM, Byers SW. E-selectin-mediated dynamic interactions of breast- and colon-cancer cells with endothelial-cell monolayers. Int J Cancer. 1995;60:426–431. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910600326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou MN, Menter DG, Konstantopoulos K, Nicolson GL, McIntire LV. Integrin alpha4beta1/VCAM-1 pathway mediates primary adhesion of RAW117 lymphoma cells to hepatic sinusoidal endothelial cells under flow. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1999;17:669–676. doi: 10.1023/a:1006747106885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roh MS, Wang L, Oyedeji C, LeRoux ME, Curley SA, Pollock RE, Klostergaard J. Human Kupffer cells are cytotoxic against human colon adenocarcinoma. Surgery. 1990;108:400–405. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800770937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curley SA, Roh MS, Feig B, Oyedeji C, Kleinerman ES, Klostergaard J. Mechanisms of Kupffer cell cytotoxicity in vitro against the syngeneic murine colon adenocarcinoma line MCA26. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:715–721. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asao T, Shibata HR, Batist G, Brodt P. Eradication of hepatic metastases of carcinoma H-59 by combination chemoimmunotherapy with liposomal muramyl tripeptide, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6254–6257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essani NA, McGuire GM, Manning AM, Jaeschke H. Differential induction of mRNA for ICAM-1 and selectins in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and endothelial cells during endotoxemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:74–82. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umansky V, Schirrmacher V, Rocha M. New insights into tumor-host interactions in lymphoma metastasis. J Mol Med. 1996;74:353–363. doi: 10.1007/BF00210630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard T, Mulsch A, Klein H, Decker K. Regulation by prostaglandin E2 of cytokine-elicited nitric oxide synthesis in rat liver macrophages. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1992;373:897–902. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1992.373.2.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiratori Y, Ohmura K, Hikiba Y, Matsumura M, Nagura T, Okano K, Kamii K, Omata M. Hepatocyte nitric oxide production is induced by Kupffer cells. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1737–1745. doi: 10.1023/a:1018879502520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay A, Bajenova O, Kelly TM, Thomas P. Carcinoembryonic antigen induces cytokine expression in Kupffer cells: implications for hepatic metastasis from colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1996;56:4805–4810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]