Directional guidance of neuronal migration in the olfactory system by the protein Slit (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2007 Oct 24.

Published in final edited form as: Nature. 1999 Jul 22;400(6742):331–336. doi: 10.1038/22477

Abstract

Although cell migration is crucial for neural development, molecular mechanisms guiding neuronal migration have remained unclear. Here we report that the secreted protein Slit repels neuronal precursors migrating from the anterior subventricular zone in the telencephalon to the olfactory bulb. Our results provide a direct demonstration of a molecular cue whose concentration gradient guides the direction of migrating neurons. They also support a common guidance mechanism for axon projection and neuronal migration and suggest that Slit may provide a molecular tool with potential therapeutic applications in controlling and directing cell migration.

Most neurons in the developing nervous system have to migrate from their birthplaces to reach their final positions. Studies of neuronal migration are important for revealing the mechanisms underlying the formation of a normal nervous system, for understanding the aetiology of human diseases caused by abnormal migration and for designing therapeutic approaches to neurological diseases.

Neuronal migration in the developing central nervous system (CNS) was initially inferred from histological observations by classical neuroembryologists including Vignal (1888), Ramon y Cajal (1891, 1911), Kolliker (1896), His (1904) and Hardesty (1904)1 (reviewed in refs 2-5). The possibility that cells truly migrate, rather than that cells formed earlier are simply displaced by cells formed later6, was supported initially by cells moving in a direction opposite to that expected from cell displacement through histological examinations in the spinal cord of chick embryos7 and later by autoradiographic tracing in the cerebrum of rodent embryos8. The fact that only nuclei were traced in autoradiographic studies raised the possibility that nuclei, but not entire cells, moved in the highly structured nervous system. Electron microscopy and reconstruction provided strong evidence for the migration of neuronal cell bodies3-5, and observations of primary neurons and glia cultured in vitro demonstrate directly that neurons do migrate9-10. Using histological, autoradiographic, retroviral tracing, dye labelling and modern imaging techniques, it has now been established that the majority of neurons migrate throughout the developing nervous system11-12.

Proper migration of neurons is essential for the formation and normal functioning of the nervous system. In humans, defects in neuronal migration can cause several diseases including epilepsy13,14. Migration is also important for metastasis and invasion of neuroblastoma and glioma. Although it has been known for some time that cell migration is essential for postnatal behaviour changes in birds, we now know that neurogenesis and neuronal migration also continue in the brains of postnatal mammals, including humans. These findings indicate that, for successful application of cell-based therapies for neurodegenerative diseases, it is essential to direct the correct migration of neurons or cells expressing therapeutic products to the target region.

Our understanding of the molecular mechanisms guiding neuronal migration is still limited. Genetic studies in humans and mice have identified many molecules, deficiencies of which cause defects in neuronal migration15. Because most of these are intracellular molecules, it is unlikely that they act as guidance cues for migrating neurons. One molecule identified from the genetic studies is the secreted protein Reelin16-18. Loss-of-function mutations in the reeler gene cause defects in CNS lamination, and Reelin has been thought to control cell–cell interactions critical for cell positioning. It is not clear, however, whether Reelin acts as a stop signal or an adhesive molecule for migrating neurons15-18,21. Because molecules can regulate neuronal migration indirectly22, it is not established whether Reelin acts directly or indirectly15,21. Similarly, the precise roles of the other genetically identified molecules involved in neuronal migration remain to be determined15,21.

The olfactory system is a useful model for studying neuronal migration. The olfactory bulb relays olfactory information from the olfactory epithelium to the primary olfactory cortex23. The major types of interneuron in the olfactory bulb, including the granule cells and the periglomerular cells, are produced postnatally from the anterior subventricular zone (SVZa) of the telencephalon in rodents24-26. Neuronal progenitors thus have to migrate in the rostral migratory stream (RMS) from the SVZa to the olfactory bulb19,20,27-32. Co-culture of explants in collagen gel matrices indicated that the septum, at the midline of the telencephalon and caudal to the SVZa, secretes a repulsive factor(s) guiding the migration of SVZa neurons31. However, experiments involving a different culture method using matrigel found no repellent activity in the septum for migrating SVZa cells32. Because the matrigel allowed neurons to migrate on top of each other, a behaviour termed chain migration and thought to occur in vivo27,28,32, the significance of the repulsive cue in the septum for guiding SVZa neurons was doubted by Wichterle et al.32. Furthermore, the molecular identity of the putative repellent(s) in the septum is not known.

We show here that the septum is repulsive to SVZa neurons in matrigel. We found the expression of two slit genes in the postnatal septum, encoding proteins that are repulsive cues capable of guiding the migration of SVZa cells. This guidance depends on a concentration gradient, rather than the absolute amount, of the Slit proteins. Moreover, Slit repels neurons migrating from the SVZa into its natural pathway, the RMS. These results indicate that Slit can act as a diffusible molecule guiding the direction of cell migration in the nervous system.

Repulsive activity in the septum

The existence of a repulsive activity in the septum for SVZa neurons was indicated by co-cultures of the SVZa and septum in collagen gel matrices31. Another assay for studying migration of SVZa neurons involves matrigel, a three-dimensional extracellular matrix gel of collagen IV, laminin, heparan sulfate proteoglycans and entactin–nidogen33. The morphology and behaviour of SVZa cells cultured in the matrigel are thought to resemble those in vivo27,28,32.

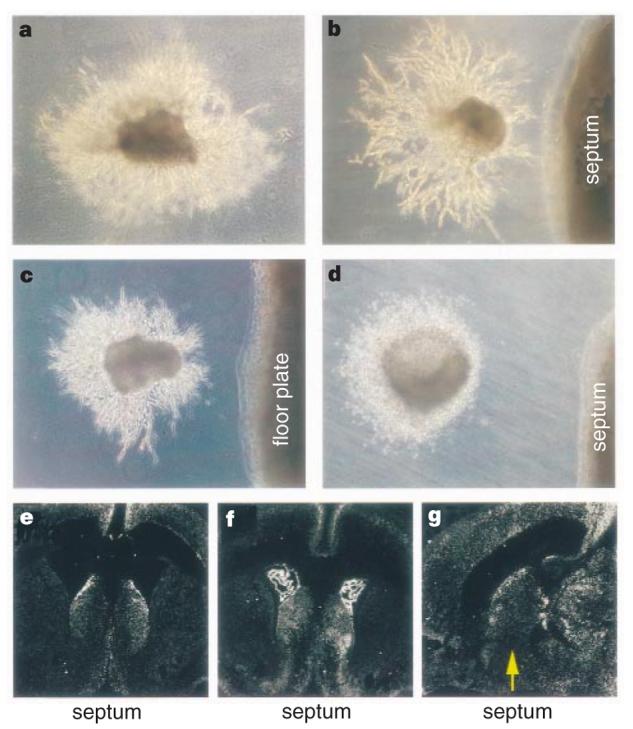

To test whether the septum is repulsive to SVZa neurons, we isolated postnatal SVZa and septal explants and co-cultured them in matrigel and collagen gel matrices. The distribution of neurons migrating out of the SVZa explants can reveal repulsive or attractive activities. When SVZa explants were placed in matrigel, the distribution of migrating cells was symmetric around the circumference of each explant (Fig. 1a). In the presence of the septum, more cells were found in the quadrant distal to the septum than those in the quadrant proximal to the septum (Fig. 1b) (36/36 explants). Thus, as in collagen gel matrices31 (Fig. 1d), the septum is repulsive to SVZa neurons. The ventral midline structure in the spinal cord, the floorplate, was also repulsive to the SVZa in matrigel (Fig. 1c) (12/12 explants). These results indicate that, although cells migrate on top of each other in matrigel27,28,32, chains of migrating cells do respond to guidance cues in the ventral midline of the neural tube, including the septum and the floorplate.

Figure 1.

Repulsion of SVZa neurons by the septum and the floorplate and expression of slit genes in the postnatal septum. a, Chains of cells migrate out of SVZa explants symmetrically when cultured alone in matrigel. In the presence of the septum (b) or floorplate (c), there are more migrating cells in the quadrant of the SVZa explant distal to the septum than in the proximal quadrant. d, As reported31, the septum is repulsive to SVZa cells in collagen gel. e, A coronal section showing expression of Slit-1 in the septum and the neocortex of postnatal day 3 (P3) rats. f, A coronal section showing expression of Slit-2 in the septum, the choroid plexus and the neocortex of P3 rats. g, A sagittal section showing expression of Slit-1 in the septum and the neocortex of P3 rats. Rostral is to the left and dorsal is up.

Repulsion of migrating neurons by Slit

Genes encoding the secreted Slit proteins, which are chemorepellents for axons34-38, are expressed in the embryonic septum34,35. We have now found that slit genes are expressed in the postnatal murine septum. Of the three slit genes, slit-1 (Slit-1) and slit-2 (Slit-2) are expressed in the postnatal septum and the neocortex (Fig. 1e-g), raising the possibility that Slit may be a guidance cue for SVZa neurons.

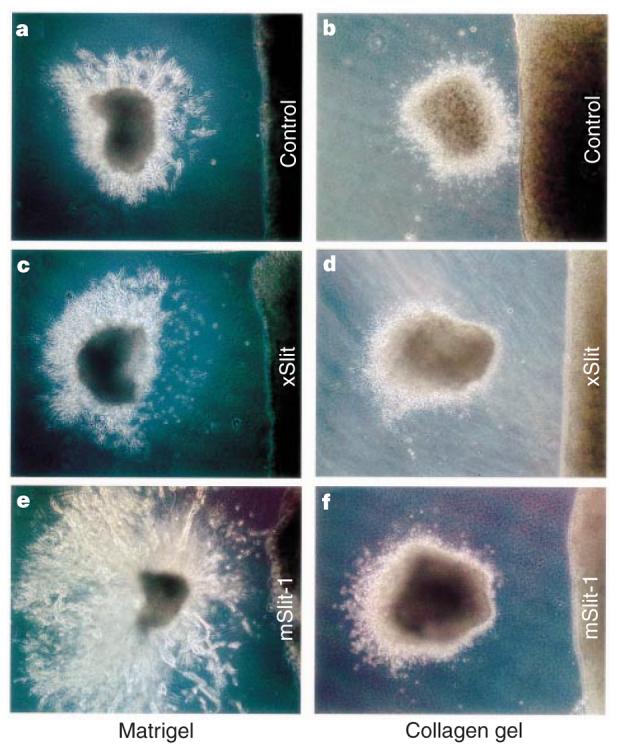

To investigate whether Slit proteins affected migration of neurons from the SVZa, we first co-cultured SVZa explants and Slit-expressing cells in matrigel. When SVZ explants from postnatal day 5 (P5) mice were co-cultured with human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells stably transfected with a control plasmid34, chains of migrating neurons were symmetrically distributed (Fig. 2a) (32/32 explants). When SVZ explants were co-cultured with HEK cells stably expressing the Xenopus Slit protein (xSlit), an orthologue of mSlit-2, chain migration was highly asymmetric (Fig. 2c) (42/42); there were more chains in the quadrant distal to the Slit cells than in the quadrant proximal to the Slit cells. The same effect occurred when SVZa explants were co-cultured with mSlit-1-expressing cells (Fig. 2e) (16/16). These results indicate that Slit is repulsive for SVZ cells migrating in chains.

Figure 2.

Effect of Slit on neurons migrating from SVZa explants. a, c, e, Distribution of chains of cells from the SVZa explants, co-cultured with an aggregate of control HEK cells (a), with cells expressing xSlit (c) or mSlit-1 (e) in matrigel for one (a, c) or two days (e). d–f, Distribution of cells migrating out of the SVZa explants after being co-cultured with control HEK cells (b), with cells expressing xSlit (d) or mSlit-1 (f) in collagen gel.

We have also assayed SVZa migration using collagen gel matrices31. Although the distribution of migrating SVZa cells was symmetric when explants were co-cultured with control cells (Fig. 2b) (104/122 explants), with xSlit cells there were more SVZa cells in the distal quadrant (Fig. 2d) (235/254 explants). Cells transiently expressing mSlit-1 have similar effects (Fig. 2f) (31/31). The effect of xSlit on SVZa cells was quantified, showing that cells in the distal quadrant were not only more numerous, but also farther away from the explants (Fig. 3d). Because single cells, rather than chains of cells, migrate in collagen gel matrices, the repulsive activity of Slit in the collagen gel assay indicates that Slit can act on single cells.

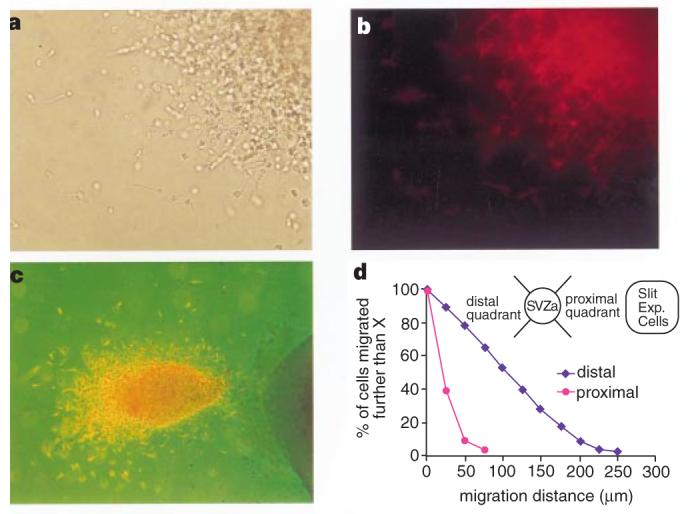

Figure 3.

Neuronal nature and distribution of SVZa neurons. a, Cells migrating out of the SVZa explant. b, The same cells as in a, stained with the TuJ1 antibody. Under different focal planes, essentially all cells are TuJ1 positive. c, Super-imposition of bright light and fluorescent views of another explant co-cultured with Slit-expressing cells. Note the asymmetric distribution of neurons within the SVZa explant. d, Quantification of the effect of Slit on migrating SVZa neurons after TuJ1 staining. X axis, distance of neurons from the edge of SVZa explants; Y axis, percentage of neurons that have migrated further than the distance indicated on the X axis. Similar results have been obtained from five experiments.

To find out whether the migrating cells were neurons, we carried out immunocytochemistry with the TuJ1 antibody, which recognizes the neuron-specific β-tubulin (Fig. 3). The migrating cells stained positive for TuJ1, confirming that they are neurons (Fig. 3a-c). The uneven distribution of TuJ1 staining within the SVZa explants indicates that neurons migrated within each explant away from the Slit cells (Fig. 3c).

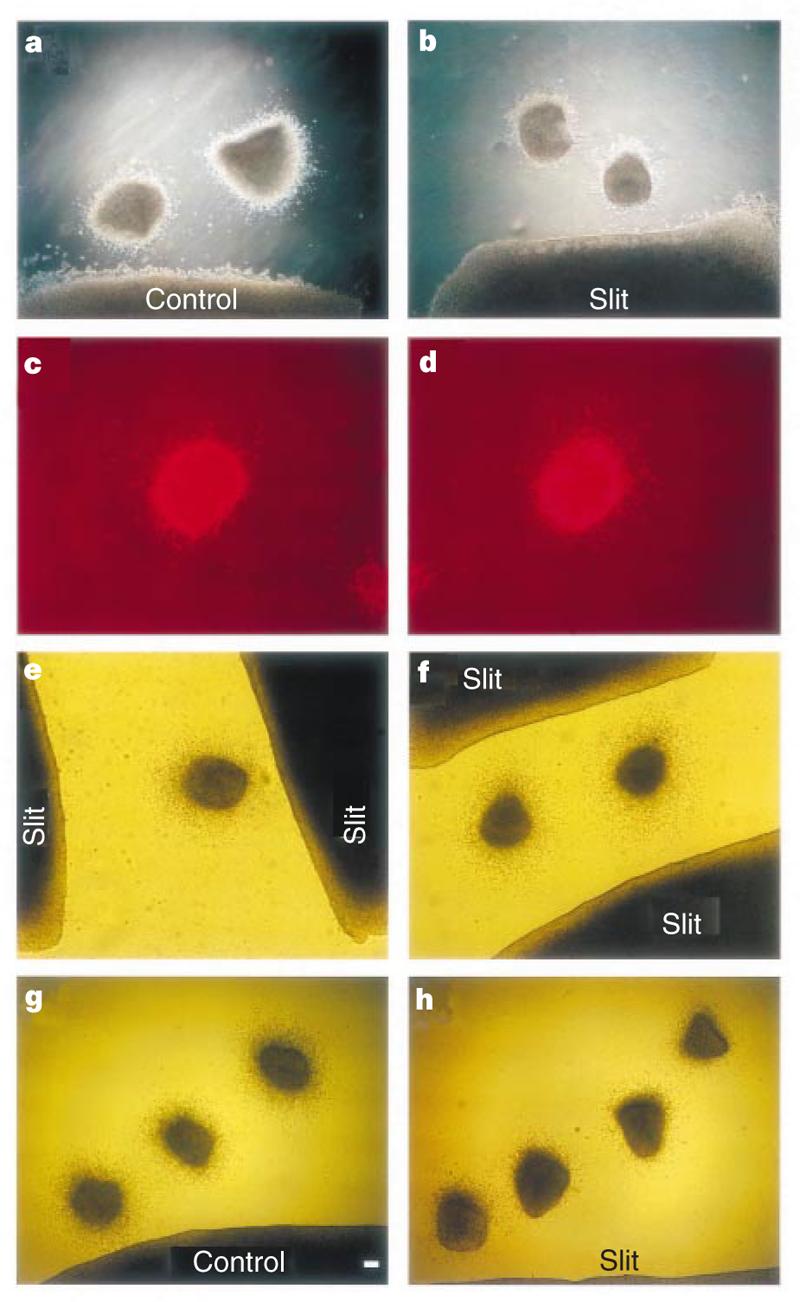

These findings could be explained in two ways: either Slit repels neurons, or Slit inhibits migration. To distinguish between them, we placed two SVZa explants at different distances from a single aggregate of Slit cells. The distance from the Slit cells to the proximal side of the more distant explant was equal to, or slightly farther than, the distance from the Slit cells to the distal side of the closer explant (Fig. 4b). In both explants there were more cells in the distal quadrants. These results are best explained by a repulsive activity of Slit, rather than inhibition of migration by Slit. Next we placed an SVZa explant on top, rather than to the side, of Slit-expressing cells. Neurons still migrated out of the SVZa (Fig. 4d) (16 explants), arguing against inhibition of neuronal migration by Slit. These results indicate that Slit is repulsive to, rather than inhibitory of, migrating neurons.

Figure 4.

Spatial relationship between SVZa explants and Slit-expressing cells. Results of co-cultures in collagen gels are shown. a, b, SVZa explants placed next to HEK cells. c, d, SVZa explants placed on top of HEK cells and migrating neurons revealed by staining with the TuJ1 antibody. e, When a single SVZa explant was placed between two aggregates of Slit cells, the asymmetric distribution of cells shows that neurons migrated according to guidance from the closer aggregate. f, When two SVZa explants were placed at an equal distance from two aggregates of Slit cells, the distribution of SVZa neurons is symmetric. g, h, Placement of multiple SVZa explants allows determination of the effective distance of Slit, with the most distal explant at ∼1 mm.

To test whether SVZa cells respond to the absolute concentration Slit or to a concentration gradient of the protein, we placed SVZa explants between two aggregates of Slit cells. When an SVZa explant was placed at unequal distances from two Slit aggregates, neurons migrated away from the closer Slit aggregate (Fig. 4e). When SVZa explants were placed at an equal distance from two Slit aggregates, the cells migrated out symmetrically (Fig. 4f). The simplest explanation for these observations is that SVZa cells respond to a concentration gradient of the Slit protein.

To determine the effective distance of Slit, multiple SVZa explants were placed at different distances from control or Slit cells. When the explants were within 1 mm of the Slit cells, neurons migrated asymmetrically (Fig. 4h).

Slit and neuronal migration in the RMS

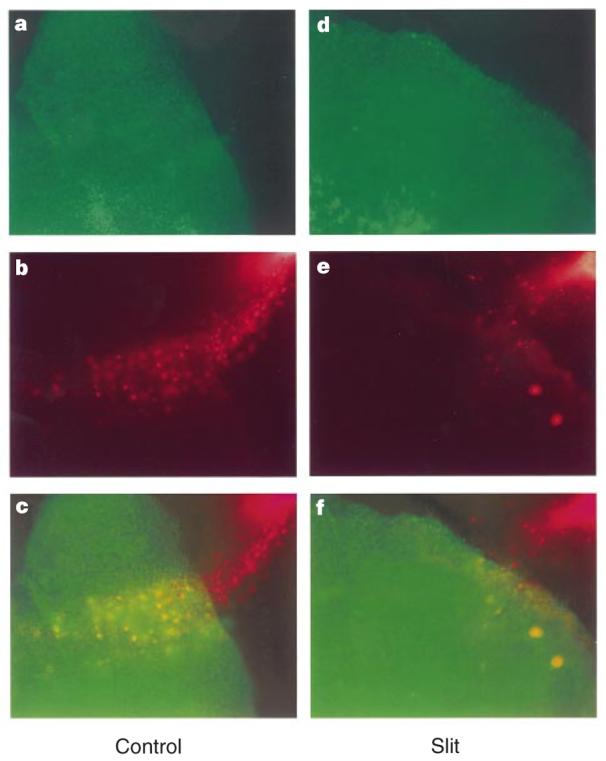

Although Slit can repel neurons migrating out of SVZa explants in collagen gels and in matrigel, the question of whether Slit can guide neurons migrating in their natural pathway was not addressed. We developed an assay to investigate the effect of Slit on neurons migrating from the SVZa into their natural pathway, the RMS, towards the olfactory bulb. Sagittal sections of postnatal brains containing the SVZa, the RMS and the olfactory bulb were isolated and cultured. Crystals of the lipophilic dye 1,1′-dioctadecyl-3,3,3′,3′-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) were placed into the SVZa to label neuronal precursors. After 24 h in culture, migrating neurons were found in the RMS (Fig. 5b). To test the effect of Slit, control HEK cells or HEK cells stably expressing Slit were pre-labelled with another lipophilic dye 3,3′-dioctadecyloxacarbocyanine (DiO), and placed on top of the RMS. With control HEK cells, SVZa neurons migrated into the RMS (Fig. 5a-c) (14/14 explants). In contrast, when Slit cells were placed on the RMS, few SVZa neurons migrated into the RMS (Fig. 5d-f) (16/16). These results provide strong evidence indicating that Slit can regulate neuronal migration in natural pathways.

Figure 5.

Migration of neurons in the RMS. DiI crystals were placed into SVZa in sagittal sections of postnatal rat brains to label cells (red in b, c, e, f) migrating into the RMS. Control or Slit HEK cells were labelled with DiO (green in a, c, d, f). a–c, different views of the same slice in which an aggregate of control HEK cells were placed on top of the RMS. d–f, Different views of the same slice in which an aggregate of Slit cells were placed on top of the RMS. In all panels, the upper right corner is towards the SVZa, the origin of the RMS, whereas the lower left corner is towards to the olfactory bulb, the end of the RMS.

Role of endogenous Slit in the septum

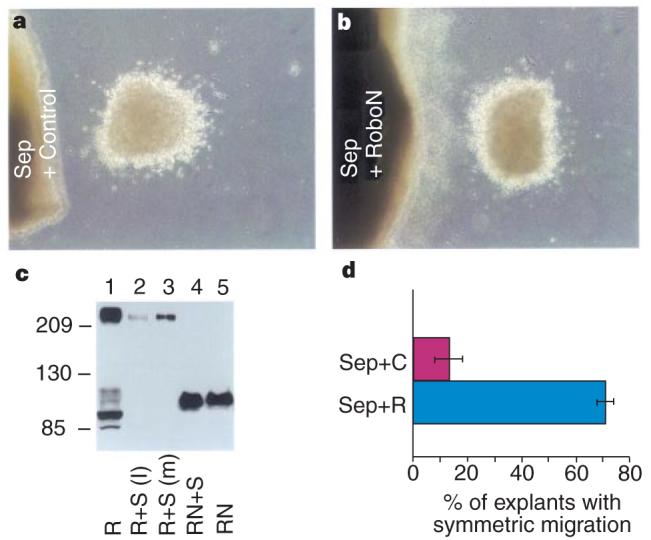

The septum contains a repulsive activity for SVZa neurons31. We have also found that slit genes are expressed in the septum and that Slit proteins are repulsive to SVZa neurons. Together, these results indicate that endogenous Slit may be involved in repelling SVZa neurons. To test directly whether endogenous Slit contributes to the repulsive activity in the septum, we constructed a plasmid that expressed RoboN, the extracellular domain of Roundabout (Robo), a receptor for Slit34,36-38. After complementary DNA transfection into HEK 293T cells, RoboN protein was secreted into the medium and could bind to the Slit protein (Fig. 6c). Because RoboN lacks the transmembrane and intracellular domains, it could be a competitive inhibitor of Slit–Robo signalling.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of the repulsive activity in the septum by RoboN. a, b, Distribution of SVZa neurons after co-culturing with septal explants on top of either control HEK cells (a) or HEK cells expressing RoboN (b). c, Binding of RoboN to Slit. Numbers on the left indicate relative molecular mass. HA-tagged full-length Robo (lane 1) and RoboN (lane 5) were detected by an anti-HA antibody; Robo was co-incubated either with Myc-tagged xSlit lysate (lane 2) or with Myc-tagged xSlit in the medium (lane 3) and Robo was detected by the anti-HA antibody after immunoprecipitation with the anti-Myc antibody. Lane 4: RoboN was co-incubated with Myc-tagged xSlit in medium and detected by the anti-HA antibody after immunoprecipitation with the anti-Myc antibody. d, Percentage of SVZa explants with symmetric migration. Sep + C, results with the septal explants cultured on top of control cells (n = 36), Sep + R, results with the septal explants cultured on top of RoboN cells (n = 73). The difference between these two groups was statistically significant (P < 0:05 in Student's _t_-test).

To investigate whether RoboN could inhibit the activity in the septum, we placed explants of the septum on top of either control HEK cells or cells expressing RoboN, and then co-cultured them with explants of the SVZa, and examined the distribution of migrating SVZa neurons. When cultured on top of the control cells, the septum was effective in repelling SVZa neurons (Fig. 6a). RoboN cells significantly reduced the number of explants with asymmetric distribution of migrating neurons (Fig. 6b, d). Although these results did not distinguish which endogenous Slit was involved, they indicate that endogenous Slit contributes to the repulsion of SVZa neurons by the septum.

Discussion

We have shown that Slit is a chemorepellent for neurons migrating from the SVZa and that Slit acts as a diffusible molecule, the concentration gradient of which guides the direction of migrating neurons. Slit is, to our knowledge, the first molecule directly shown to be sufficient for the directional sensing of migrating neurons. With previous findings that Slit is an axon repellent34-38, these results also support the idea that there are at least some molecular guidance mechanisms in common between axon projection and neuronal migration.

Slit is a secreted protein34-38. Our data indicate that Slit can guide neuronal migration without contact between the cells responding to Slit and those producing Slit. It is unlikely that Slit acts indirectly by regulating the differentiation of HEK cells or cells in the SVZa explants. The repulsion of individual neurons by Slit in collagen gels further supports the idea that Slit acts directly on migrating neurons. Our studies have shown that Slit is a repulsive cue, rather than an inhibitory factor, for migrating neurons. The behaviour of SVZa explants at different distances from two Slit sources indicates that the concentration gradient of Slit is likely to be responsible for directional sensing. The ephrins can prevent neural crest cells from migrating on caudal somites39-41. Although the fact that ephrins are membrane-anchored proteins makes it unlikely that they act as diffusible guidance cues, it remains to be seen whether Slit and ephrins share any molecular mechanisms.

In the olfactory system, interneuron precursors migrate several millimetres in the RMS from the SVZa to the olfactory bulb. The activities of the septum and Slit indicate that Slit should be able to guide at least the initial migration of cells from the SVZa. It is not clear whether a gradient of Slit is responsible for guiding neuronal migration in the entire RMS. In our experiments with SVZa explants, the Slit cells could not act at distances greater than 1 mm. However, it cannot be ruled out that an endogenous Slit gradient could be laid down by the septum over a longer time over the entire RMS. It is also possible that other cues, acting in or around the RMS, may affect the migration of SVZa cells. Because significant influence over the direction of SVZa cell migration was only exerted by the septum, but not by the target tissue (the olfactory bulb or by tissues surrounding the RMS31, it seems reasonable to suppose that, if other molecules help to guide SVZa migration, they may act not just by themselves, but in coordination with Slit. Molecules such as the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), which is expressed in the RMS and is necessary for SVZa migration30,42,43, may act locally in the migration pathway to allow adhesion of SVZ neurons. It will be interesting to test whether there is any functional relationship between Slit and NCAM. The embryonic septum can repel embryonic olfactory bulb axons and neonatal SVZa neurons, whereas the neonatal septum can repel only migrating neonatal SVZa neurons but not embryonic olfactory bulb axons31. The expression and activity of slit in both embryonic and neonatal septum indicate that either different forms of Slit proteins may be responsible for axon guidance and neuronal migration, or there may be other molecules modulating the activity of the same Slit proteins. Although only the caudal, not the rostral, septum has been shown to repel SVZa neurons31, our in situ hybridization has not revealed obvious differences in the expression of slit genes in the rostral and caudal septum, again raising the possibility of other modulating activities.

Functional studies of Slit make it interesting to consider the relationship between neuronal migration and axon guidance. Both processes involve cell motility, but the entire cell body moves in one case, whereas only axons move in the other case. Defects in both axon pathways and neuronal position can be caused by mutations in the same genes. Loss-of-function mutations in netrin, its Caenorhabditis elegans homologue unc-6 or their receptors result in abnormal axon projection and cell position in the mouse44-46 and C. elegans47. Genetic and phenotypic analyses in C. elegans indicate that unc-6 is required for the migration of mesodermal cells47. Experiments with commissural and other explants have demonstrated that Netrin-1 can directly guide axon projections44, and recent evidence from explant studies indicates that defects in pontine neuronal migration in mouse mutants similarly reflect a direct attractive action of Netrin-1 on these neurons (K. Lee, H. Simon, M. Tessier-Lavigne and D. O'Leary, personal communication). It will be interesting to see if the same is true of other cell migration defects reported in mice mutant for Netrin or Netrin receptors, or whether some of them are due to indirect effects on the projection of axons or glial fibres along which neurons may migrate (see ref. 48 for review of neurophilic and gliophilic migration).

Genetic and explant experiments indicate that Slit acts directly as a chemorepellent for axons34,35,37,38. Mutations in robo and slit in C. elegans and Drosophila result in defective cell positioning, suggesting that Slit–Robo signalling is required for cell migration37,49. Genetic and phenotypic analysis in Drosophila suggests that slit is required for the migration of muscle precursor cells37; certain muscle precursor cells, which normally migrate away from the embryonic midline, do not migrate in slit mutants (T. Kidd and C. S. Goodman, personal communication). Our present results have shown directly that Slit is sufficient to act as a repellent for migrating neurons. Slit has therefore been directly demonstrated to guide both neuronal migration and axon projection34-38. It seems that whether Slit guides the movement of cell bodies or axons depends on the type of responding cell. It is unclear, however, whether intracellular machinery or extracellular mechanisms determine the type of response. Is the same form of Slit protein involved? Are there more intracellular components to enable a neuron to move its cell body? Or does the absence of critical components cause a neuron to move its cell body rather than its axon? The availability of a guidance cue acting in vitro on both migrating neurons and projecting axons offers the prospect of addressing these questions experimentally.

Cell migration is crucial in other developmental and non-developmental processes, including migration of cortical neurons radially along glial fibres, migration of neural-crest precursor cells, gastrulation, heart formation, muscle development, angiogenesis, leukocyte chemotaxis and tumour metastasis. We have obtained evidence for Slit function in other populations of neurons50, indicating that guidance cues may be crucial in many processes involving neuronal migration. It will therefore be interesting to test whether the Slit family or other guidance cues can guide migrating cells in multiple systems in normal and abnormal situations. For migrating cells that do not respond to Slit, it will be interesting to investigate whether the introduction of Robo or other potential receptor components can confer responsiveness to Slit. This may broaden potential therapeutic applications of Slit proteins in controlling unwanted cell migration and in delivering cells to the intended target region.

Methods

In situ hybridization

Brains were removed from P3 rats, and 16-μm coronal sections were cut with a cryostat, collected on superfrost plus slides and air dried. 35S-labelled slit probes were made and 2 × 106 counts per minute (c.p.m.) of riboprobes was applied to each slide with brain slices. The slides were overlaid with coverslips and incubated in humidified chambers at 55 °C overnight before being washed with a washing buffer (50% formamide, 2 × SSC and 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol) at 65 °C for 30 min, rinsed for 10 min in RNase buffer (0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 5 mM EDTA) and treated for 30 min at 37 °C with 20 μg ml−1 RNase A. The slides were then placed at 65 °C in the washing buffer for 5 min at 37 °C in 2 × SSC for 15 min and at 37 °C in 0:1 × SCC for 15 min before being dehydrated. The slides were coated with Kodak NTB2 emulsion and stored at 4 °C for 3 weeks before being developed in Kodak D19 and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Co-culture of explants

Brains from newborn Sprague-Dawley rats (postnatal days 3–7) were embedded in 7% low melting-point agarose prepared in phosphate-buffered saline. Coronal and sagittal sections of 400 mm were cut with a vibratome. Tissue within the borders of the SVZ in coronal sections was dissected out to make SVZa explants of 200–400 mm in diameter. We isolated septal explants from sagittal sections and placed them into the collagen gel or matrigel as described31,32,34. They were cultured for 16–24 h under 5% CO2 in F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, and penicillin and streptomycin.

Co-culture of SVZa explants with cell aggregates

We have two stable HEK cell lines34. One was transfected with a plasmid expressing xSlit, and the other with the vector plasmid. Both lines went through similar selection and subcloning. The Slit line was confirmed by western blotting to express the full-length xSlit protein tagged with the Myc epitope. We also transiently transfected HEK 293 cells with either a vector or a plasmid expressing full-length Myc-tagged mSlit-1. The expression of mSlit-1 was also confirmed by western analysis. Because xSlit and mSlit-1 behaved similarly in all tests, we usually used the xSlit stable line.

We made aggregates of the control or Slit-expressing cells by the hanging-drop method. They were placed into collagen gels or matrigel with SVZa explants, and cultured as described above.

For immunohistochemistry, samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and pre-incubated with 10% goat serum in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 1 h. Incubation with the primary antibody (TuJ1, 1:200 dilution) was carried out overnight at 4 °C. They were washed and then incubated with a goat anti-mouse secondary antibody conjugated to Cy3 for 1 h at room temperature, and washed before being mounted with glycerol.

For quantification, we obtained immunofluorescence images of samples stained with TuJ1, using a Zeiss microscope. We quantified cell distribution by analysing the distance between the cell body and the nearest edge of the explant, using the IPLab program.

To test whether the extracellular domain of Robo (RoboN) could inhibit the septal activity, aggregates were made from HEK cells transiently transfected with a plasmid expressing RoboN. These cells were embedded in a thin layer of collagen gel. Explants of the caudal septum were placed on top of the RoboN cells and co-cultured with SVZa explants in collagen gel matrices.

Slice assay with the RMS

Sagittal sections of postnatal rats were cut with a vibratome and those containing the SVZa, the RMS and the olfactory bulb were used. Crystals of DiI were inserted into the SVZa. The slices were cultured in a similar way to the SVZa explants.

Control or Slit-expressing HEK cells were labelled with DiO. Aggregates of these cells were placed on top of the RMS. We visualized DiI and DiO signals with different filters under the microscope. Images were taken with a Spot camera and stored on the computer.

Binding of RoboN to Slit

Full-length Robo has 1,660 residues; RoboN was made by tagging a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope to amino-acid residue 718. Lysates of cells expressing HA-tagged full-length Robo or RoboN were incubated with lysates or media of cells expressing xSlit. Immunoprecipitation was done as described34.

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Yuan and D. Ornitz for mouse slit cDNAs; J. Xu, Q. Wang and L. Zhou for help with in situ hybridization; W. Gan and J. Lichtman for help with confocal imaging and analysis; J. Brunstrom and A. Pearlman for discussions; C. S. Goodman and M. Tessier-Lavigne for comments; NIH, NSFC and SCST for support; and the John Merck Fund, NSFC and the Leukemia Society of America for scholar awards (to Y.R. and J.Y.W.).

References

- 1.Hardesty I. On the development and nature of the neuroglia. Am. J. Anat. 1904;3:229–268. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cajal SR. In: Histology of the Nervous System. Swanson N, Swanson LW, editors. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic P. Neuron–glia relationship during granule cell migration in developing cerebellar cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1971;141:283–312. doi: 10.1002/cne.901410303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakic P. Guidance of neurons migrating to the fetal monkey neocortex. Brain Res. 1971;33:471–476. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(71)90119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakic P. Mode of cell migration to the superficial layers of fetal monkey neocortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 1972;145:61–84. doi: 10.1002/cne.901450105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilney F. Behavior in its relation to the development of the brain. Part II. Correlation between the development of the brain and behavior in the albino rat from embryonic states to maturity. Bull. Neurol. Inst. NY. 1933;3:252–358. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levi-Montalcini R. The origin and development of the visceral system in the spinal cord of the chick embryo. J. Morphol. 1950;86:253–278. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angevine JB, Jr, Sidman RL. Autoradiographic study of cell migration during histogenesis of cerebral cortex in the mouse. Nature. 1961;192:766–768. doi: 10.1038/192766b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hatten ME, Liem RHK. Astroglia provide a template for the positioning of developing cerebellar neurons in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 1981;90:622–630. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatten ME, Liem RHK, Mason CA. Two forms of glial cells interact differently with neurons in vitro. J. Cell Biol. 1984;98:193–204. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.1.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray GE, Leber SM, Sanes JR. Migratory patterns of clonally related cells in the developing central nervous system. Experientia. 1990;46:929–940. doi: 10.1007/BF01939386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh C, Cepko C. Cell lineage and cell migration in the developing cerebral cortex. Experientia. 1990;46:940–947. doi: 10.1007/BF01939387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman MG, McGillivray BC, Kalousek DK, Hill A, Poskitt KJ. In: Congenital Malformations of the Brain: Pathologic, Embryological, Clinical, Radiological and Genetic Aspects. Norman MG, editor. Oxford Univ. Press; New York: 1995. pp. 223–277. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon N. Epilepsy and disorders of neuronal migration. II: Epilepsy as a symptom of neuronal migration defects. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1996;38:1131–1134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1996.tb15077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pearlman AL, Faust PL, Hatten ME, Brunstrom JE. New directions for neuronal migration. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998;8:45–54. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falconer DS. Two new mutants ‘trembler’ and ‘reeler’, with neurological actions in the house mouse. J. Genet. 1951;50:192–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02996215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D'Arcangelo G, et al. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature. 1995;374:719–723. doi: 10.1038/374719a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hirotsune S, et al. The reeler gene encodes a protein with an EGF-like motif expressed by pioneer neurons. Nature Genet. 1995;10:77–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0595-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luskin MB. Restricted proliferation and migration of postnatally generated neurons derived from the forebrain subventricular zone. Neuron. 1993;11:173–189. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90281-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frotscher M. Cajal-Retzius cells, Reelin, and the formation of layers. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1998;8:570–575. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(98)80082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rio C, Rieff HI, Qi P, Corfas G. Neuregulin and erbB receptors play a critical role in neuronal migration. Neuron. 1997;19:39–50. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80346-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farbman AI. In: Smell and Taste in Health and Disease. Getchell TV, et al., editors. Raven; New York: 1991. pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis I: a longitudinal investigation of the kinetics, migration and transformation of cells incorporating tritiated thymidine in neonate rats, with special reference to postnatal neurogenesis in some brain regions. J. Comp. Neurol. 1966;127:337–390. doi: 10.1002/cne.901260302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hinds JW. Autoradiographic study of histogenesis in the mouse olfactory bulb. II cell proliferation and migration. J. Comp. Neurol. 1968;134:305–322. doi: 10.1002/cne.901340305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman J. Autoradiographic and histological studies of postnatal neurogenesis IV: cell proliferation and migration in the anterior forebrain, with special reference to persisting neurogenesis in the olfactory bulb. J. Comp. Neurol. 1969;137:433–458. doi: 10.1002/cne.901370404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Long-distance neuronal migration n the adult mammalian brain. Science. 1994;264:1145–1148. doi: 10.1126/science.8178174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lois C, Garcia-Verdugo J-M, Alvarez-Buylla A. Chain migration of neuronal precursors. Science. 1996;271:978–981. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zigova T, et al. A comparison of the patterns of migration and the destinations of homotopically transplanted neonatal subventricular zone cells and heterotopically transplanted telencephalic ventricular zone cells. Dev. Biol. 1996;173:459–474. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hu H, Tomasiewics H, Magnuson T, Rutishauser U. The role of polysialic acid in migration of olfactory bulb interneurons precursors in the subventricular zone. Neuron. 1996;16:735–743. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hu H, Rutishauser U. A septum-derived chemorepulsive factor for migrating olfactory interneuron precursors. Neuron. 1996;16:933–940. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wichterle H, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Direct evidence for homotypic, glia-independent neuronal migration. Neuron. 1997;18:779–791. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80317-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kleinman HK, McGravey ML, Liotta LA, Robey PG, Tryggvason K, Martin GR. Isolation and characterization of type IV procollagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate proteoglycan from the EHS sarcoma. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6188–6193. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li HS, et al. Vertebrate Slit, a secreted ligand for the transmembrane protein roundabout, is a repellent for olfactory bulb axons. Cell. 1999;96:807–818. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen Ba-Charvet KT, et al. Slit2-mediated chemorepulsion and collapse of developing forebrain axons. Neuron. 1999;22:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80702-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang KH, et al. Purificaton of an axon elongation- and branch-promoting activity from brain identifies a mammalian Slit protein as a positive regulator of sensory axon growth. Cell. 1999;96:771–784. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kidd T, Bland KS, Goodman CS. Slit is the midline repellent for the Robo receptor in Drosophila. Cell. 1999;96:785–794. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brose K, et al. Evolutionary conservation of the repulsive axon guidance function of Slit proteins and of their interactions with Robo receptors. Cell. 1999;96:795–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krull CE, et al. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith A, Robinson V, Patel K, Wilkinson DG. The EphA4 and EphB1 receptor tyrosine kinases and ephrin-B2 ligand regulate targeted migration of branchial neural crest cells. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:561–570. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang HU, Anderson DJ. Eph family transmembrane ligands can mediate repulsive guidance of trunk neural crest migration and motor axon outgrowth. Neuron. 1997;18:383–396. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81240-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ono K, Tomasiewicz H, Magnuson T, Rutishauser U. N-CAM mutation inhibits tangential neuronal migration and is phenocopied by enzymatic removal of polysialic acid. Neuron. 1994;13:595–609. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rousselot P, Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Embryonic (PSA) N-CAM reveals chains of migrating neuroblasts between the lateral ventricle and the olfactory bulb of adult mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 1995;351:51–61. doi: 10.1002/cne.903510106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Serafini T, et al. Netrin-1 is required for commissural axon guidance in the developing vertebrate nervous system. Cell. 1996;87:1001–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fazeli A, et al. Phenotype of mice lacking functional Deleted in colorectal cancer (Dcc) gene. Nature. 1997;386:796–804. doi: 10.1038/386796a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ackerman SL, et al. The mouse rostral cerebellar malformation gene encodes an UNC-5-like protein. Nature. 1997;386:838–842. doi: 10.1038/386838a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedgecock EM, Culotti JG, Hall DH. The unc-5, unc-6, and unc-40 genes guide circumferential migrations of pioneer axons and mesodermal cells on the epidermis in C. elegans. Neuron. 1990;4:61–85. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90444-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rakic P. Principles of neural migration. Experientia. 1990;46:882–891. doi: 10.1007/BF01939380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zallen JA, Yi BA, Bargmann CI. The conserved immunoglobulin superfamily member SAX-3/Robo directs multiple aspects of axon guidance in C. elegans. Cell. 1998;92:217–227. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80916-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu Y, Li HS, Zhou L, Wu JY, Rao Y. Cellular and molecular guidance of GABAergic neuronal migration from an extracortical origin to the neocortex. Neuron. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80801-6. in the press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]