Polypyrimidine Track-binding Protein Binding Downstream of Caspase-2 Alternative Exon 9 Represses Its Inclusion* (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2007 Dec 17.

Published in final edited form as: J Biol Chem. 2000 Dec 14;276(11):8535–8543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008924200

Abstract

We have been using the caspase-2 pre-mRNA as a model system to study the importance of alternative splicing in the regulation of programmed cell death. Inclusion or skipping of a cassette-type exon in the 3′ portion of this pre-mRNA leads to the production of isoforms with antagonistic activity in apoptosis. We previously identified a negative regulatory element (In100) located in the intron downstream of alternative exon 9. The upstream portion of this element harbors a decoy 3′ acceptor site that engages in nonproductive commitment complex interactions with the 5′ splice site of exon 9. This in turn confers a competitive advantage to the exon-skipping splicing pattern. Further characterization of the In100 element reveals a second, functionally distinct, domain located downstream from the decoy 3′ acceptor site. This downstream domain harbors several polypyrimidine track-binding protein (PTB)-binding sites. We show that PTB binding to these sites correlates with the negative effect on exon 9 inclusion. Finally, we show that both domains of the In100 element can function independently to repress exon 9 inclusion, although PTB binding in the vicinity of the decoy 3′ splice site can modulate its activity. Our results thus reveal a complex composite element that regulates caspase-2 exon 9 alternative splicing through a novel mechanism.

Pre-mRNA alternative splicing is an important mechanism for higher eucaryotes to regulate cell type- and developmental stage-specific gene expression. It provides a potential for an extraordinarily high level of diversity in generating multiple, often functionally distinct, protein isoforms from a single gene. In addition to the basic splicing signals (5′ splice site, branch point sequence and pyrimidine tract-AG), numerous sequence elements have been identified in exons or introns that can influence in various ways the function of the splicing machinery (reviewed in Refs. 1-3). These regulatory elements can, in some cases, mediate their effects in cis, for example, through the formation of stem-loop structures (e.g. Ref. 4), although they will usually interact with trans-acting factors. Such factors often form multicomponent complexes that can contain combinations of known constitutive splicing factors, including hnRNPs,1 snRNPs, and serine-arginine (SR) proteins as well as novel specific alternative splicing factors (e.g. Refs. 5-7). However, little is known about the precise mechanisms by which these specific complexes interact with and influence the function of the splicing machinery. Similarly, the process of splice site selection in complex pre-mRNAs is still a poorly understood phenomenon (8-10).

One mechanism for intronic elements to function in repressing splicing was first described in Drosophila. The sex-specific splicing factor Sex-lethal (SXL) regulates the splicing of transformer (tra) pre-mRNA by competing with U2AF65 for binding to the polypyrimidine tract of the regulated 3′ splice site. This permits the use of an alternative 3′ splice site that is normally not selected, thus resulting in the production of a functional TRA protein only in female flies (11-16). Direct competition with constitutive splicing factors has been shown to be a conserved strategy for vertebrate alternative 3′ splice site choice and often involves the polypyrimidine tract binding protein (PTB/hnRNP I) (15, 17-19). PTB was first identified ∼10 years ago (20, 21) and then found to have features of an hnRNP protein (22). It was only recently that PTB was recognized as an important player in alternative splicing regulation (reviewed in Ref. 23). Nevertheless, the precise mechanism by which PTB influences splicing is still unclear, even though it has been implicated in the alternative splicing of a number of genes.

We have been using the caspase-2 (also known as Ich-1 (interleukin-1_β_ converting enzyme homologue 1) or Nedd2) pre-mRNA as a model system to study the importance of alternative splicing regulation in the process of programmed cell death (24). Inclusion or skipping of 61-base pair exon 9 in the 3′ end of this pre-mRNA leads to the formation of two mRNAs encoding protein isoforms with antagonistic activities in apoptosis (25). CASP-2L is derived from the skipping of alternative exon 9 and can induce cell death in a variety of cells (25-29). CASP-2S is a truncated version of the protein produced because of a premature termination codon created by the inclusion of exon 9. Overexpression of CASP-2S has been shown to prevent apoptotic death (25, 30). Recently, the generation of caspase-2-deficient mice has provided evidence that suggests an important role for caspase-2 as both a positive and negative cell death effector (31). We have previously implicated SF2/ASF and hnRNP A1 as modulators of caspase-2 exon 9 alternative splicing (24). Using a systematic mutagenesis approach, we have identified an intronic regulatory element (In100) located 140 nucleotides downstream of exon 9, that can repress inclusion of the alternative exon. The upstream portion of that element harbors sequences highly resembling a typical 3′ acceptor site. We have shown that this upstream region can behave as a normal 3′ splice site in certain conditions and can promote the assembly of stable U1 snRNP-dependent complexes on the 5′ splice site of nearby exon 9. Based on our results, we proposed a model in which this region would act as a “decoy” 3′ acceptor site, engaging in nonproductive splicing complexes with the 5′ splice site of the alternative exons, thus competitively favoring the pairing of exons 8 and 10 (32). We now show that PTB interacts with a region downstream of the decoy 3′ acceptor site in In100 and represses inclusion of the alternative exon. Furthermore, we find that each domain of the In100 element can function independently to repress exon 9 inclusion using distinct mechanisms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Constructions and Splicing Substrates

C2 and C3 have been described previously (24). Various portions of the In100 element were amplified using PCR with specific oligonucleotides. Each fragment was either inserted in pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) in front of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter or at a _Bgl_II site in intron 9 of C3 to generate the respective C3 derivative (e.g. C3In50up, C3In50dn). In50upΔ and In50dnΔ were generated using overlapping mutagenic oligos. Oligos were hybridized, blunt-ended using Klenow fragment polymerase and inserted either in pcDNA3 or at a _Bgl_II site in intron 9 of C3 to generate C3In50upΔ and C3In50dnΔ. Specific mutations were introduced in the upstream (In100upΔ) or downstream (In100dnΔ) portion of the In100 fragment using “PCR overlap-extension mutagenesis” (33). Mutagenic fragments were digested and substituted back into the C2 plasmid DNA. PCR was again used to mutate exon 9 3′ splice site AG to a CU. This fragment was then substituted into C3In50up, C3In50upΔ, C3In50dn, or C3In50dnΔ) at _Hin_dIII and _Bam_HI sites to generate the respective 553 derivative. C3i9 consists of the Ex9−10 splicing unit with the In100 sequences deleted. i9 and i9In100 were generated by linearizing the corresponding C3i9 or C2i9 (containing In100) plasmid at the _Bgl_II site described above. i9In50up and i9In50dn were generated in a similar manner from the corresponding C3 constructs. Plasmids containing small fragments of the element were linearized at a _Bam_HI site (present in 3′ oligos), and all C2 and C3 derivatives were linearized at an _Xho_I site in exon 10.

Transfections and RT-PCR

HeLa cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and were seeded at ≈2 × 105 cells/well in a six-well dish, 24 h prior to transfection. Transfection was done using a standard calcium phosphate precipitation procedure with 3 _μ_g of DNA. Transfection efficiency was routinely ≈60%, as evaluated by cotransfection with a green fluorescent protein marker. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and the RNA extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, Inc.). Spliced products derived from the expressed minigenes were detected using RT-PCR as described previously (24) and resolved on 6% polyacrylamide 1× TBE gels.

In Vitro Splicing Assays

Splicing substrates were synthesized using T7 RNA polymerase (Promega) except for i9 derivatives, which was with T3 RNA polymerase. Final concentrations of reagents were as follows in a 10-_μ_l reaction: 500 ng of linearized DNA template, 0.4 mm ATP and CTP, 0.1 mm GTP and UTP, 0.84 mm GpppG cap analogue (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), 10 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 unit/_μ_l RNasin (Promega), 1× Transcription Buffer (Promega), 20 _μ_Ci of [_α_-32P]UTP, and 1 unit/_μ_l RNA polymerase. Samples were then treated with 0.1 unit/_μ_l DNase I (Promega) for 15 min and ethanol-precipitated, and the full-length transcripts were gel-purified as described (34). Synthesis of cold competitor RNAs was in a scaled-up 100-_μ_l reaction with the following modifications: 0.5 mm UTP and 0.42 mm cap analogue were used, and [_α_-32P]UTP was omitted. HeLa cell nuclear extracts were prepared according to previously established protocols and contained ≈20 mg/ml total proteins (35). Splicing reactions were set up and processed as previously described (36) except that some batches of nuclear extracts were supplemented with 1 unit of creatine kinase (Sigma). 2 fmol of RNA substrates was added and the samples incubated at 30 °C for 2 h unless otherwise mentioned. For trans-competition experiments, 0.5−1 pmol of cold RNAs were pre-incubated with nuclear extracts at 30 °C for 10 min prior to addition of the substrate and incubation under splicing conditions. Splicing products were resolved on 8% polyacrylamide, 8 m urea gels. The identity of lariat molecules was determined by performing a debranching reaction in a S100 extract (37) followed by gel migration alongside molecular weight markers. The other products were identified according to size and comigration with pertinent partial splicing substrates.

UV Cross-linking Assays

Splicing reactions were set up as above except that higher specific activity radiolabeled substrates were used. Trans-competition assays were carried out as above, except that 350−500 fmol of cold RNA competitors were used and the pre-incubation was for 10 min on ice. 6-_μ_l aliquots were transferred onto a 96-well microtiter plate previously cooled at −20 °C and irradiated with ≈1 Joule in a UV Stratalinker 1800 (Stratagene). Samples were then treated for 30 min. at 37 °C with one volume of RNase A (5 mg/ml). Radiolabeled cross-linked proteins were boiled for 5 min in 1× SDS loading buffer and separated on 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Histidine-tagged PTB expression vector was a gift from Dr. J. G. Patton and was expressed and purified from Escherichia coli as described (38). Purified U2AF65 was a generous gift from Dr. Rui-Ming Xu. Histidine-tagged hnRNP A1 was expressed and purified from E. coli using standard procedure.

Immunoprecipitation Assays

Cross-linking was carried out as described above except that, following the RNase treatment, samples were incubated with 20% fetal calf serum (as a normal serum control) or with various antibodies. Pre-blocked Protein A/G-agarose beads were then added with further incubation and gentle rocking. The RNA-labeled proteins retained on the beads after several washings were eluted and resolved on SDS-PAGE.

Electrophoretic Separation of Splicing Complexes

This procedure was adapted from Refs. 39 and 40. 4-_μ_l aliquots were removed from standard splicing reactions at indicated time points and mixed with 1 _μ_l of heparin at 1 mg/ml. 0.5 _μ_l of loading buffer (1× TBE, 20% glycerol, 1% bromephenol blue, and 1% xylene cyanol) was then added and the samples loaded on nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels (acrylamide: bisacrylamide = 80:1), which had been pre-electrophoresed at 200 V for 30 min in 50 mm Tris-glycine. Electrophoresis was then continued under the same conditions for 4−5 h at room temperature. ATP depletion of the nuclear extracts was achieved as in Ref. 41 by pre-incubating the extracts at room temperature for 20−30 min. without addition of hexokinase and glucose. ATP, MgCl2, and creatine phosphate were omitted from these splicing reaction mixtures.

RESULTS

The In100 Element Can Be Separated into Two Functionally Distinct Regions

Deletion mutagenesis experiments revealed a negative regulatory element (In100) located in the intron downstream of alternative exon 9 (Ref. 32 and Fig. 1_B_, compare lanes 1 and 2). To assess the potential involvement of transacting factors and dissect the functional domains of the In100 element, a series of small RNAs corresponding to various regions of the element (Fig. 1_A_) were produced in vitro and used in splicing trans-competition assays. Specifically, cold RNA competitors (0.5−1 pmol) were mixed with HeLa splicing reactions and pre-incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. 32P-Labeled pre-mRNA substrates were then added and the incubation continued for 2 h. When added in trans to a splicing reaction containing C2 substrates, the In100 RNA promoted a complete shift toward the production of the casp-2S exon 9-inclusion mRNA (Fig. 1_B_, lane 3). This was detected by monitoring the relative ratio of casp-2S to casp-2L mRNAs and corresponding lariat molecules (see Fig. 1_B_;a black arrow represents casp-2L, and a white arrow marks casp-2S products/intermediate). This observation suggested that In100 mediated its negative effect on exon 9 inclusion at least in part through the involvement of trans-acting factors. These factors are titrated away by the excess amount of In100 competitor RNA and the inhibition is relieved. The same de-repression could also be observed with RNA competitors spanning the entire 3′ portion of the element (In75dn and In50dn; Fig. 1_B_ (lanes 7 and 8) and see Fig. 3). In contrast, competitor RNAs spanning the upstream (In50up, In75up, In30up, and In20up) portion of the element were unable to induce any shift in the splicing profile when added in trans (Fig. 1, B (lanes 4−6) and A, respectively). This is consistent with the presence of a sequence resembling a 3′ acceptor site in this region, which may act as a decoy 3′ splice site for interacting with the 5′ splice site of exon 9 (32). According to this model, the exon-skipping splicing pattern would be competitively favored over the exon inclusion through a cis-mediated mechanism and this fragment would not be expected to have any effect when added in trans. Finally, a centrally located fragment as well as a minimal RNA transcript spanning the last 25 nucleotides of the In100 element were also unable to release the inhibition of exon 9 inclusion (Fig. 1_B_, lanes 9 and 10 and lanes 11 and 12, respectively). These results thus define a minimal region (In50dn; denoted in black in Fig. 1_A_) downstream of the decoy 3′ splice site in In100 that requires interaction with nuclear factors for its activity.

Fig.1. The In100 element can be dissected into two functionally distinct regions.

A, structure of the C2 substrate and RNA competitors used. C3 is identical to C2 except that In100 is deleted. B, in vitro splicing assays in the presence of cold competitor RNAs. HeLa nuclear extracts were pre-incubated for 10 min at 30 °C in the presence of 0.5−1 pmol of cold competitor RNAs (as indicated above each lane). 32P-Labeled C2 substrate was then added with the incubation continued under splicing conditions for 2 h. The positions of casp-2S and casp-2L mRNAs and splicing intermediates are indicated by open and black triangles, respectively. Addition of cold In100 or In75dn RNAs led to a shift toward more inclusion of exon 9, whereas In50up, In25dn, or In40 did not have the effect.

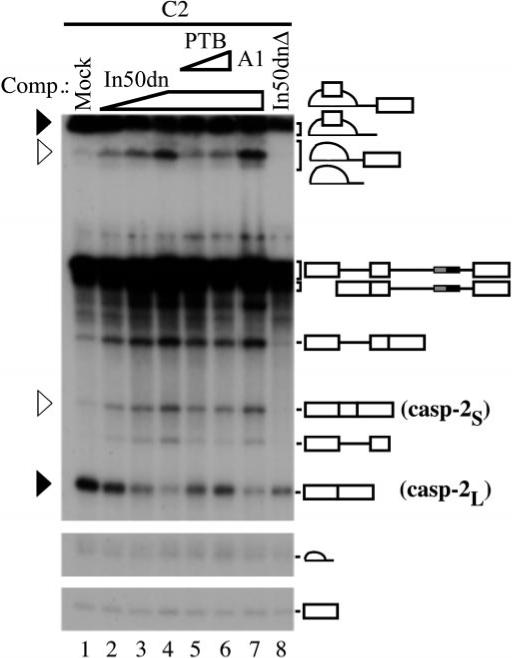

Fig.3. PTB can repress exon 9 inclusion.

Splicing reactions were carried out as before with In50dn added in trans to de-repress exon 9 inclusion (lanes 2−4). Following pre-incubation with cold In50dn RNA, purified His-tagged PTB (lanes 5 and 6) or hnRNP A1 (lane 7) was added to the reaction and the incubation continued for 2 h. De-repression was reversed by addition of purified PTB (lanes 5 and 6) but not by hnRNP A1 (lane 7). No de-repression was detected when In50dnΔ RNA was used as a competitor in trans (lane 8). The positions of casp-2S and casp-2L mRNAs, and splicing intermediates are marked by open and black triangles, respectively.

PTB Specifically Interacts with the In100 Regulatory Element

We used a UV cross-linking assay as a first step toward the identification of nuclear factors interacting with In100. HeLa nuclear extracts were first pre-incubated under splicing conditions with the respective RNA competitors before C2 substrates were added and the samples UV-irradiated for 10 min. Following RNase treatment, the covalently cross-linked, RNA-labeled proteins were resolved on SDS-PAGE. Using this method, we identified two bands with apparent molecular masses of 60 and 35 kDa, respectively, that were specifically competed away by the addition of cold In100 RNA in trans (Fig. 2_B_, compare lanes 2 and 3 with lane 1). The 60-kDa protein could be titrated away specifically by the In50dn fragment, whereas the 35-kDa protein was competed away by the In50up fragment (Fig. 2_B_, lanes 6 and 7 and lanes 4 and 5, respectively). These results show that functionally distinct domains of the In100 regulatory element are recognized by different protein factors. Several observations led us to consider PTB as a likely candidate for the 60-kDa band observed on SDS-PAGE in our cross-linking experiments. First, putative PTB-binding sites are present in the In50dn portion of the element (see Fig. 2_A_): specifically, two copies of the “core” PTB consensus motif UCUU(C) within a pyrimidine-rich context (38) and two copies of the UUCUCU(CU), which was identified previously as a candidate PTB splicing repressor motif (19, 42). Second, PTB was one of the known splicing factors in this range of molecular weight. Third, longer gel migrations resolved the 60-kDa species as a doublet, typical of PTB. To test whether the 60-kDa cross-linking band was PTB, we used a cross-linking assay followed by immunoprecipitation with specific antibodies. Specifically, a labeled RNA substrate consisting of the complete In100 element was used in UV cross-linking as before (Fig. 2_C_, lane 1) except that aliquots were taken, incubated with antibodies, and the immunoselected proteins recuperated using Protein A/G-agarose beads. Using this strategy, we show that a monoclonal antibody directed against PTB was able to immunoprecipitate specifically the 60-kDa doublet cross-linked on In100 (Fig. 2_C_, lane 3). In contrast, no proteins were selected if a control serum or an unrelated antibody was used (Fig. 2_C_ (lane 2) and data not shown, respectively). These results clearly identify the 60-kDa band as PTB.

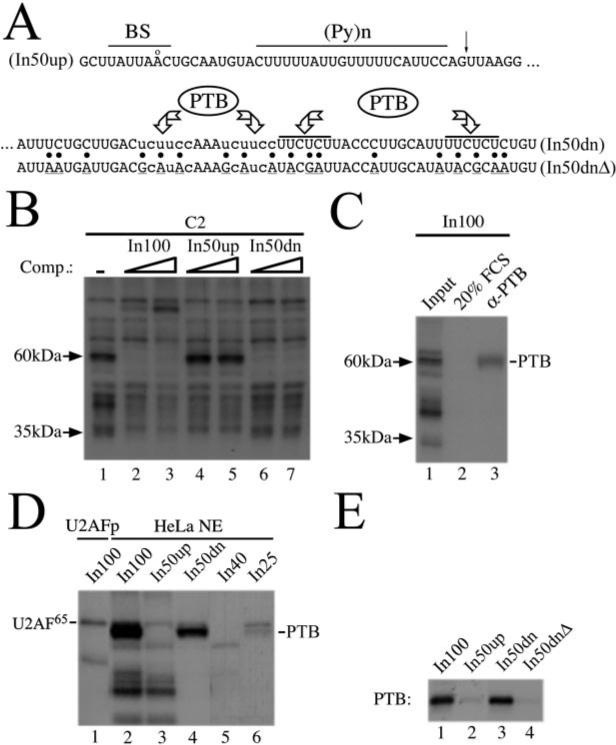

Fig.2. PTB specifically interacts with the In100 regulatory element.

A, putative PTB binding sites are indicated above the sequence. The core PTB consensus motifs UCUU(C) are in lowercase, and the UUCUCU(CU) motifs identified previously as candidate PTB splicing repressor sites (Refs. 19 and 42) are indicated by a line. Also marked are the splicing signals in the decoy 3′ acceptor site (BS; consensus: YNYYRÅY, where Y represents pyrimidines; R, purine, and N, any nucleotide) followed by a long stretch of pyrimidines ((pY)n) and (NY)AG (putative 3′ cleavage site is indicated by an arrow). B, two specific bands are revealed by UV cross-linking/competition experiments. Splicing reactions were set up as before using the C2 substrate with In100, In50up, or In50dn as cold RNA competitor (0.25−0.5 pmol). Aliquots were UV-irradiated and treated with RNase A, and the RNA-labeled proteins resolved on 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Arrows indicate positions and sizes of cross-linked proteins specifically interacting with distinct portion of the In100 element. C, UV cross-linking/immunoprecipitation experiment. Samples were processed as before for cross-linking except that antibodies were added following the RNase A treatment. After incubation on ice, protein A/G-agarose beads were mixed in and the incubation continued at 4 °C. The beads were then thoroughly washed, and the retained proteins were resolved on 12.5% SDS-PAGE. FCS, fetal calf serum. D, a UV cross-linking experiment was carried out as before with various portions of In100 as labeled RNA transcripts in the presence of HeLa nuclear extracts or purified U2AF65. Position of the PTB doublet is indicated on the right. E, UV cross-linking experiment was carried out using purified His-tagged PTB with different labeled RNA transcripts as shown above the autoradiograph.

We next wanted to map precisely where PTB was binding on the In100 element. To do this, 32P-labeled short RNA substrates (see Fig. 1_A_) were used to carry out the UV cross-linking assay as described above. As expected, PTB in the nuclear extract cross-linked exclusively on the In50dn region of the element (Fig. 2_D_, compare lane 4 to lane 3). Furthermore, consistent with the distribution of the PTB-binding sites, the entire In50dn fragment was required for strong binding of PTB, and an RNA containing only two (In25) or one (In40) out of four sites (see Figs. 1_A_ and 2_A_) permitted only a weak interaction or no detectable interaction (Fig. 2_D_, lanes 6 and 5, respectively). This suggested that PTB may bind cooperatively on the PTB-binding site array, although we have not yet studied in detail the precise stoichiometry of this interaction. The other protein species cross-linked to In100 (including the 35-kDa species) all seem to interact specifically with the In50up fragment, with the exception of U2AF65, which cross-linked with equivalent efficiency to both In50up and In50dn substrates (Fig. 2_D_, compare lanes 3 and 4). The identity of U2AF65 was assessed on the basis of its comigration with purified U2AF65 cross-linked on In100 as well as by immunoprecipitation with a specific antibody (Fig. 2_D_, compare lanes 2−4 with lane 1 and Ref. 32).

Finally, we used site-specific mutagenesis to confirm that the consensus PTB-binding sites were indeed required to maintain strong PTB cross-linking to In50dn. Multiple purine insertions were made in each of the four sites present in In50dn, and the mutated fragment was used in a UV cross-linking assay using purified histidine-tagged PTB (In50dnΔ; Fig. 2_A_). As was observed in the nuclear extract, His-PTB cross-linked specifically with the In50dn RNA substrate, and the signal of this cross-linking is as strong as that detected with the total In100 element (Fig. 2_E_, lanes 1−3). As expected, no detectable cross-linking was observed when the In50dnΔ was used (Fig. 2_E_, lane 4). Taken together, these results revealed a specific interaction of PTB with consensus CU-rich sequences located in the downstream portion of In100.

PTB Can Repress Exon 9 Inclusion

To address the functional significance of PTB binding to the In100 element, we used the in vitro splicing competition assay. Splicing reactions were carried out using the C2 substrate (which contains In100) with increasing amounts of cold In50dn RNA added in trans as described (see Fig. 1). This promoted a concentration-dependent derepression of exon 9 inclusion (Fig. 3, lanes 2−4). Addition of purified His-PTB protein to this de-repressed reaction shifted the splicing profile back toward the exon 9 skipping splicing profile (Fig. 3, lanes 5 and 6). In contrast, addition of similar amounts of purified histidine-tagged hnRNP A1 or other RNA-binding proteins to the de-repressed reaction had no effect on the splicing profile (Fig. 3, lane 7 and data not shown). Finally, In50dnΔ, in which PTB binding sites were mutated (see Fig. 2_E_), was unable to promote derepression of exon 9 inclusion when used as a trans-competitor (Fig. 3, lane 8). These results strongly suggest a role for PTB binding to In50dn in the repression of alternative exon 9 inclusion.

Both Domains of the In100 Element Can Function Independently to Repress Exon 9 Inclusion

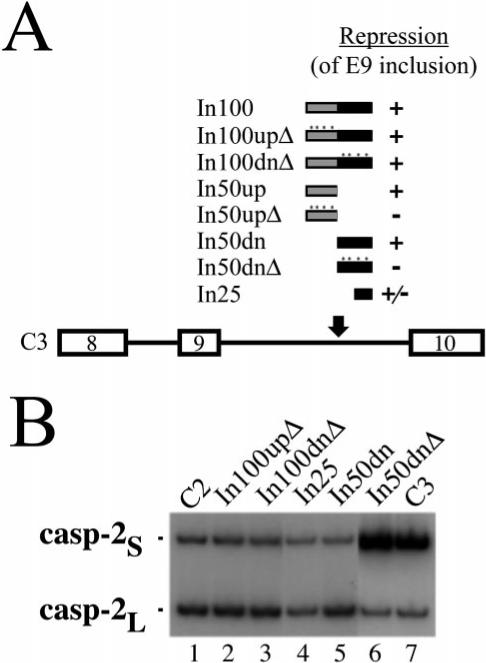

The upstream portion of the In100 element, which acts as a decoy 3′ acceptor site can facilitate the skipping of exon 9 on its own, i.e. when the downstream PTB-binding region is deleted from the substrate (32). In this isolated context, mutating all of the 3′ splice site signals (branch point, Py-tract, and AG dinucleotide) abolished completely the effect of In50up (see In50upΔ in Fig. 4_A_). In contrast, when tested in the context of the C2 substrate, i.e. in the presence of both portions of the element, these mutations had no effect on the splicing profile (Fig. 4, A (_In100up_Δ) and B (lane 2)). One possible explanation for these observations is that in this particular situation, PTB binding to the downstream portion of In100 was responsible for the repression observed. To test this hypothesis, we mutated the PTB-binding sites either in the context of the complete In100 element or in the isolated In50dn (see Fig. 4_A_, _In100dn_Δ and _In50dn_Δ, respectively). The mutant DNA constructs were transfected in HeLa cells and the resulting splicing products were analyzed using RT-PCR with oligonucleotides located in the flanking exons 8 and 10. First, mutating PTB-binding sites downstream of the “functional” decoy acceptor site while keeping In50up intact had no effect on the level of exon 9 inclusion (Fig. 4_B_, lane 3). Similarly, complete removal of the upstream portion of the In100 element (In50up) while retaining In50dn did not promote any change in the splicing profile (Fig. 4_B_, lane 5), suggesting In50dn could indeed function on its own to inhibit exon 9 inclusion. Supporting this idea, mutating the CU-rich PTB-binding sequences in this context, in the absence of In50up, promoted a strong derepression of exon 9 inclusion, indicating the involvement of PTB binding in the negative effect (Fig. 4_B_, lane 6). Interestingly, retaining only two out of four PTB-binding sites in In50dn yielded an intermediate effect on the splicing profile (Fig. 4_B_, lane 4), suggesting again the requirement of multiple PTB molecules interacting with the element to maintain sufficient repression. These results demonstrate that each domain of the In100 element, the upstream “decoy 3′ splice site” sequence and the downstream PTB binding region, can function independently of each other to repress alternative exon 9 inclusion.

Fig.4. Both domains of In100 can function independently.

A, structure of C3 substrates with the various fragments reinserted in the downstream intron 9. The level of repression of exon 9 inclusion mediated by each fragment is indicated by + or – signs. B, C3 derivatives were transfected into HeLa cells. Cells were harvested 48 h after transfection, and RNA splicing products were detected using RT-PCR. The positions of products derived from casp-2S and casp-2L mRNAs are as indicated.

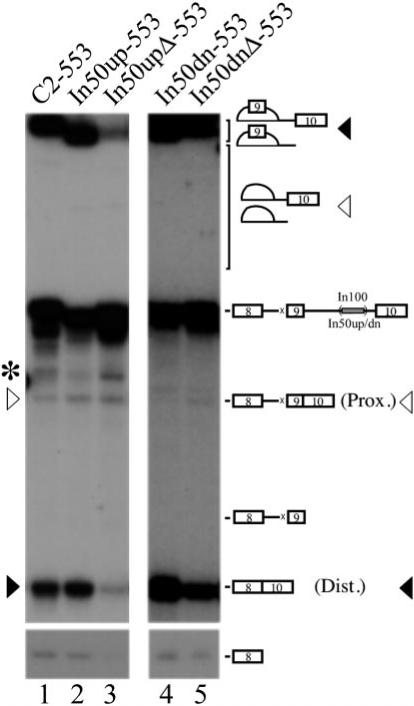

PTB Can Affect 5′ Splice Site Selection

The complete In100 element was shown to be able to negatively affect 5′ splice site selection of exon 9 in the context of a substrate where the 3′ splice site of the alternative exon 9 is mutated (32). According to the decoy 3′ acceptor site model we proposed for In50up, it is expected that this domain should be functionally active in the context of such a 553 substrate. On the other hand, we were interested in testing if PTB binding to In50dn could also affect 5′ splice site selection. To address these questions, the In50up and In50dn fragments (wild-type and mutated) were individually inserted in C3−553 to replace the In100 sequence. The splicing profile of these substrates was assessed in vitro following incubation in HeLa nuclear extracts under splicing conditions. As expected, in the presence of the In50up fragment, splicing proceeded principally to the distal 5′ splice site of exon 8 (Fig. 5, compare lane 2 to lane 1). Mutating the branch site, Py-tract, and the AG dinucleotide in In50up abolished this inhibitory effect on the proximal 5′ splice site and shifted the relative splicing profile from 90% distal 5′ splice site usage to ∼50% usage of both splice sites (Fig. 5, lane 3). We observed that these mutations also reduced overall splicing efficiency. Interestingly, the In50dn fragment also affected 5′ splice site selection and led to predominant usage of the distal 5′ splice site (Fig. 5, In50dn-553, lane 4). Mutating the CU-rich sequences in In50dn promoted a small, but reproducible, shift in the relative splicing ratio, from 90% distal/10% proximal to ∼70% distal/30% proximal (Fig. 5, _In50dn_Δ-553, lane 5). This result suggests that, in this In50dn-containing substrate, PTB binding may be required for its effect on 5′ splice site selection. Since in this context, the splicing machinery has to choose between two competing 5′ splice sites for pairing with a common downstream 3′ splice site, one attractive hypothesis is that PTB might act at the level of U1 snRNP binding. We have performed a specific RNase H protection assay to monitor U1 snRNP occupancy on each respective 5′ splice site (32, 43-45). No significant difference in the profile of U1 snRNP-dependent protection was observed using this assay whether the In50dn element was present in the transcript or not (data not shown). This suggests that the repression effect of PTB on the alternative exon 9 inclusion is likely mediated by influencing events other than U1 snRNP binding (see “Discussion”).

Fig.5. In50dn can affect 5′ splice site selection.

Substrates were incubated in HeLa nuclear extracts for 2 h under splicing conditions. Position of the splicing products generated from the use of the proximal (Prox.) or distal (Dist.) splice site is indicated by a white or black rectangle, respectively. The asterisk on the left denotes aberrant splicing products not reproducibly observed in our splicing reactions.

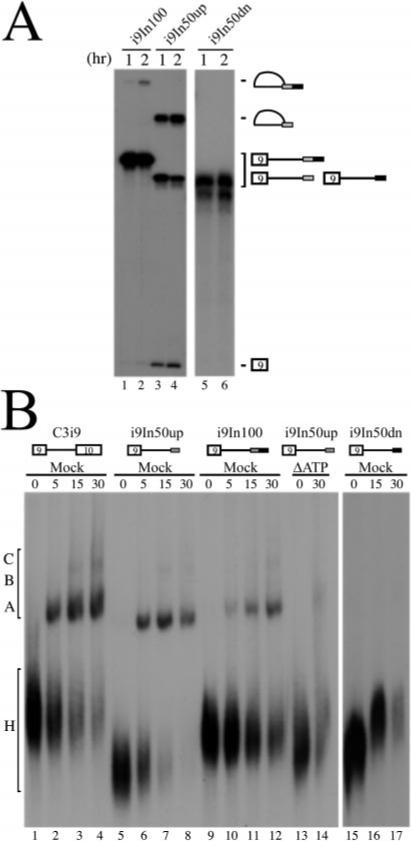

PTB Binding Sites Downstream of the Decoy 3′ Acceptor Site Can Modulate Its Recognition

Although we had observed that each of the two domains of In100 element could function independently, we were intrigued by their juxtaposed arrangement in the pre-mRNA and asked if they could influence each other in any way. If placed in a substrate containing only exon 9 with its 5′ splice site and no downstream 3′ splice site, In100 could be used as a bona fide 3′ acceptor site in this i9In100 substrate, although with greatly reduced efficiency (Fig. 6_A_ (lanes 1 and 2) and Ref. 32). In contrast, In50dn could not be used as a 3′ acceptor site when placed downstream of exon 9 in an isolated i9In50dn substrate (Fig. 6_A_, lanes 5 and 6). However, utilization of the decoy 3′ acceptor site increased 5-fold if the In50dn domain was deleted from i9In100 to yield i9In50up (Fig. 6_A_, lanes 3 and 4). This suggested that PTB binding to In50dn may affect the recognition of the decoy 3′ splice site and the formation of spliceosome complexes on this site. We then compared splicesome assembly on minimal substrates containing or lacking PTB binding sites. When incubated in Hela nuclear extracts under splicing conditions, the i9In100 substrate, which contains the intact In100 element, supported the formation of apparently normal spliceosomal complexes A, B, and C. However, the splicing complex formation was much less efficient (or less stable) with i9In100 than with C3i9, a substrate containing the natural 3′ splice site of exon 10 (see Ref. 32 and Fig. 6_B_, compare lanes 9−12 with lanes 1−4, respectively). When tested in this assay, i9In50up, which does not contain the PTB-binding sites, promoted the formation of a slightly faster migrating complex (Fig. 6_B_, lanes 5−8). In addition, this complex formed very efficiently on i9In50up, as can be assessed by the level of substrate already converted into the retarded species at the 15-min time point (Fig. 6_B_, compare lane 8 with lane 12). Interestingly, in contrast to normal U2-dependent splicesomal complexes that are ATP-dependent, this complex was partially resistant to ATP depletion (Fig. 6_B_, lanes 13 and 14). Finally, consistent with the results obtain in splicing assays, the presence of In50dn by itself did not promote formation of any complexes detectable by native gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6_B_, lanes 15 and 16). Taken together, these results show that, under certain conditions, PTB is capable of modulating the activity of the adjacent In50up element, possibly by promoting the formation of a distinct, aberrant complex on the decoy 3′ acceptor site.

Fig.6. PTB binding sites downstream of the decoy 3′ acceptor site can modulate its recognition.

A, standard splicing reactions (2 h) were set up using substrates containing exon 9 and its 5′ donor site with downstream intron sequences containing In100, In50up, or In50dn. Position of lariat intermediates and 5′-exon generated by the first step of the splicing reaction is indicated. B, gel electrophoresis analysis of splicing complexes formed on In100 or other labeled RNAs as depicted above the autoradiograph. Aliquots from standard splicing reactions were taken at times indicated above each lane, and splicing complexes were resolved on a native Tris-glycine gel. The small gray rectangle depicts In50up. The small black rectangle represents In50dn. Heterogeneous (H) and spliceosomal complexes (A, B, and C) are indicated on the left.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized a repressor element (In100) located in the intron downstream of caspase-2 alternative exon 9. We have showed previously that the upstream portion of this element consists of a decoy 3′ acceptor site that interacts nonproductively with the 5′ splice site of the alternative exon, which in turn competitively favors skipping of exon 9. We now uncover in this element a second functionally distinct domain (In50dn) juxtaposed downstream of the decoy 3′ acceptor site. PTB binding to CU-rich motifs in In50dn correlated well with the repressor activity of this domain. Interestingly, this negative effect of PTB binding site-containing In50dn can also be observed in the context of competing 5′ splice sites. Finally, we provide evidence supporting that PTB can modulate recognition of the adjacent decoy 3′ acceptor site and discuss the possible implications for regulation.

In100 Contains Two Domains

The In100 element is composed of two juxtaposed subdomains that can repress exon 9 inclusion using distinct mechanisms. This bipartite architecture is also found in other exonic or intronic elements, although in those cases it usually involves the overlapping of positive and negative elements (19, 42, 46-50). In a few instances, two different types of splicing enhancers (e.g. Pu-rich and CA-rich) were found in the same exon (51-54). Another example of an intronic repressor that can be separated into two mechanistically distinct subelements was identified in the hnRNP A1 pre-mRNA downstream of the alternative exon 7B; however, the mechanism of action is different (55). The upstream portion of hnRNP A1 intronic element can specifically repress the 3′ splice site of the alternative exon, and the downstream portion binds hnRNP A1 and may interact with a second hnRNP A1 molecule bound in the upstream intron, thus favoring exon skipping through a looping-out of the alternative exon (55). We have observed that the complete In100 element can also negatively affect the 3′ splice site selection of exon 9 although we have not yet characterized which domain of the element was responsible for this effect (Côté and Wu, unpublished results). A recent study suggests that intrinsically defective splice sites and negative elements play important roles in distinguishing the authentic constitutive splice sites from the vast number of pseudo-splicing signals (56). Interestingly, the In100 element in the casp-2 pre-mRNA presents just this architecture: a pseudo-splice site juxtaposed with a repressor element. Our results suggest that the adjacent repressor element may help in preventing the decoy 3′ splice site from being used in splicing. A data base search suggests that In100 sequence motif, a decoy 3′ splice site juxtaposed to a pyrimidine-rich element, may be present in other genes undergoing alternative splicing and may represent a general intronic splicing regulatory element (data not shown). The involvement of such a pseudo-splice site in alternative splicing regulation might explain the phylogenic conservation of pseudo-splicing signals in mammalian introns. Further investigation is necessary to prove the generality of such splicing regulatory motifs.

PTB Can Repress Exon 9 Inclusion

PTB has been implicated in the alternative splicing of several pre-mRNAs (15, 17, 19, 38, 42, 57-62). Nevertheless, how PTB mediates its negative effect on splicing is still unclear. In one scenario, PTB was found to bind in the 3′ splice site region of some alternative exons, preventing constitutive splicing factors to recognize these sites. This is the case in the GABAA receptor _γ_-2 pre-mRNA, where multiple PTB binding sites are clustered around the branch site of a neurospecific exon and prevent efficient binding of U2 snRNP (19). Direct competition for binding with U2AF65 was also reported in the repression of mutually exclusive exons in the _α_- and _β_-tropomyosin pre-mRNAs (15, 17). In other cases, there may be complex mechanisms involved. In the GABAA receptor _γ_-2 pre-mRNA, the PTB binding sites upstream cooperate with another PTB site in the alternative exon itself to down-regulate splicing of the downstream intron, thus suggesting an effect of PTB on the use of the downstream 5′ splice site (19). Interestingly, similar to what we observed with In100, this effect was highly dependent on the presence of a competing splicing event (19, 32). A somewhat similar mechanism was also described for the regulation of the Src N1 alternative exon, where PTB binding to the upstream polypyrimidine tract represses splicing of the downstream intron (42). In this case, however, the inhibition was not dependent on the presence of a competing splice site (63). It was recently shown that PTB also assembled onto a repressor element downstream of the N1 exon (64). A model was proposed in which cooperative assembly of PTB on each side of the alternative exon could promote bridging of the N1 exon, similar to what was suggested for the hnRNP A1 pre-mRNA (55, 64). This model could also be envisioned for the _α_-tropomyosin pre-mRNA since PTB interacts with specific elements in the introns flanking mutually exclusive exon 3 and plays a role in repressing both its 3′ splice site as well as its 5′ splice site (38, 59). In contrast, several observations argue against such a model for the role of PTB in regulating alternative splicing of the caspase-2 pre-mRNA. First, the In100 element requires the context of competing splicing events to mediate its effect. Second, we could not detect any PTB binding to the upstream intron and this intron could be substituted for a different intronic sequence (from the human _β_-globin gene) without affecting In100 activity (32). Finally, PTB-binding sites in the casp-2 In100 regulatory element are adjacent to a decoy 3′ splice site, and our results suggest that the binding of PTB downstream of this decoy splice site prevents effective usage of that site by the splicing machinery. Therefore, the regulatory role of PTB in casp-2 alternative splicing and its mechanism of action appear to be distinct from previously described systems.

To gain some more insights into the mechanism by which PTB acts, we have used 553 splicing substrates harboring the wild type (binds PTB) or mutated (no PTB binding) In50dn fragment (see Fig. 5, In50dn-553 and _In50dn_Δ-553, respectively). We observed that abolishing PTB binding to In50dn increased the ratio of proximal to distal 5′ splice site utilization, which suggested that PTB was mediating its negative effect by somehow modulating recognition of the alternative exon 5′ splice site. Interestingly, this effect on 5′ splice site selection did not appear to be mediated through a direct reduction of U1 snRNP-dependent complexes, although we cannot exclude the possibility that a transient interaction with the U1 particle might not be detectable in the RNase H protection assay used. Alternatively, later steps in 5′ splice site scanning could be affected (e.g. U6 snRNA interaction with the 5′ splice site). Finally, the effect observed upon mutation of the In50dn element in the context of these 553 substrates is partial as compared with the respective substrates containing intact acceptor sites. This could suggest that an intact 3′ splice site is required upstream of the alternative exon, possibly because of favorable exon-bridging interactions that would permit its optimal inclusion. However, upon complete deletion of the intronic element, even in the context of 553 substrates, a full switch to proximal 5′ splice site utilization is observed (32). Therefore, we think that either residual binding of PTB and/or binding of other factors to the mutated element is responsible for the partial switch.

Involvement of Other Trans-acting Factors

We have focused our discussion exclusively on PTB in the preceding section, but it is clear that additional sequence elements and trans-acting factors are also involved in the alternative splicing of these various pre-mRNAs. Similarly, in the caspase-2 pre-mRNA, PTB binding to In50dn is most likely part of a coordinated mechanism (including the decoy 3′ acceptor site) for maintaining the low level of inclusion of exon 9 in most cell types. There may be additional trans-acting factors involved in this event. In this sense, we have previously reported that certain SR proteins as well as hnRNP A1 were able to modulate exon 9 alternative splicing (24), although this effect could be observe independently of the presence of In100 in the pre-mRNA.2 Nevertheless, this does not necessarily rule out the possibility of a cross-talk between two distinct regulatory pathways in specific cellular contexts. We have not yet been able to identify the 35-kDa protein that specifically interacts with the In50up portion of the element (see Fig. 2_B_). In addition, we have noticed the appearance of a new cross-linked species upon addition of increasing amount of cold In100 RNA competitor in trans (see Fig. 2_B_, lanes 2 and 3). It is possible that sequestering of PTB or the 35-kDa protein with large amounts of In100 RNA permits the binding of a regulatory protein to the casp-2 pre-mRNA. This could reflect certain physiological situations in which the repression of exon 9 inclusion needs to be relieved, for instance, in neuronal cells where significantly more exon 9 inclusion has been observed. Finally, a unique 50-kDa band was also detected when the minimal In40 RNA was used in UV cross-linking experiments (see Fig. 2_D_, lane 5). One potential candidate for this 50-kDa protein is CUG-BP/hNab50, a conserved 50-kDa hnRNP protein that has been associated with certain splicing phenotype in myotonic dystrophy (66, 67). Interestingly, it was recently proposed that CUG-BP could compete for PTB binding on a repressor element upstream of a neurospecific exon in the clathrin light chain B pre-mRNA (68). Further experiments will be required to determine the identity of these proteins as well as their role in caspase-2 alternative splicing regulation.

Caspase-2 Alternative Splicing Regulation

The results presented in Figs. 4 and 6 might seem somewhat difficult to reconcile, namely each domain of the element is able to work independently of the other in inhibiting exon 9 inclusion, suggesting they are functionally redundant, although they mediate their effect via distinct mechanisms. On the other hand, the presence of PTB-binding sites immediately downstream of the 3′ acceptor site in In50up can suppress the usage of this 3′ splice site. This effect of PTB-binding sites was also examined by monitoring the formation of spliceosomal complexes. When PTB-binding sites are present, seemingly normal complexes are formed, but with greatly reduced efficiency (see Fig. 6_B_, lanes 9−12). In contrast, the decoy 3′ acceptor site by itself without the downstream PTB-binding sites promoted the more efficient formation of a faster migrating complex that is now partially resistant to ATP depletion. One possibility consistent with the results shown in Fig. 6 is that PTB binding in the vicinity of the decoy 3′ acceptor site may contribute to the suppression of the usage of the decoy splice site as a normal 3′ splice site. It is conceivable that the weaker PTB binding at other sites in the pre-mRNA may be sufficient to silence the decoy 3′ acceptor site in In50up when the In50dn domain is not present. In support of this hypothesis, two additional UCUU motifs can be found just upstream of In100 and cross-linking experiments are indicative of a residual binding of PTB in the absence of In100 (32). Alternatively, this bipartite arrangement might be required only in tissues where inclusion of exon 9 needs to be de-repressed and where additional factors may be involved (e.g. neurons). Interestingly, identification of a brain-enriched form of PTB (nPTB) has been reported (19, 42, 69). Recently, it was reported that this nPTB and the previously known PTB show significant differences in their properties (65). Specifically, nPTB binds more strongly than PTB to the downstream conserved sequence regulatory element in the c-src pre-mRNA, while being a weaker repressor of splicing in vitro (65). It is an attractive possibility that this new PTB protein might also interact with In50dn in neuronal tissues.

It is our hope that further investigation in these avenues will reveal new information on the communication among different components of the splicing machinery as well as between spliceosome and signal transduction pathways.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Smitha Rajasekhar and Michael Nolan for their excellent technical assistance as well as Dr. Zhi-Hong Jiang, who has initiated this project. We thank Drs. Marc T. McNally and Woan-Yuh Tarn for their generous gifts of 2′-_O_-methyl oligos, and Dr. Rui-Ming Xu for providing purified U2AF65. Drs. Gideon Dreyfuss, Maria Carmo-Fonseca and Adrian Krainer have generously provided antibodies against hnRNP C and A1, U2AF65, and SF2/ASF, respectively. We are grateful to Drs. Benoit Chabot, Douglas Black, James G. Patton, and Marco Blanchette for providing various reagents, helpful discussions, and critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants (to J. Y. W.).

Footnotes

1

The abbreviations used are: hnRNP, heteronuclear ribonucleoprotein; PTB, polypyrimidine track-binding protein; snRNP, small nuclear ribonucleoprotein; oligo, oligonucleotide; RT, reverse transcription; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PAGE, polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; nPTB, brain-enriched form of polypyrimidine track-binding protein.

2

Z. Jiang and J. Y. Wu, unpublished results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams MD, Rudner DZ, Rio DC. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1996;8:331–339. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang J, Manley JL. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997;7:205–211. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80130-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AJ. Annu. Rev. Genet. 1998;32:279–305. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.32.1.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanchette M, Chabot B. RNA. 1997;3:405–419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siebel CW, Fresco LD, Rio DC. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1386–1401. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.8.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou MY, Rooke N, Turck CW, Black DL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:69–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNally LM, McNally MT. J. Virol. 1999;73:2385–2393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2385-2393.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Black DL. RNA. 1995;1:763–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reed R. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2000;12:340–5. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chabot B. Trends Genet. 1996;12:472–478. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(96)10037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sosnowski BA, Belote JM, McKeown M. Cell. 1989;58:449–459. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue K, Hoshijima K, Sakamoto H, Shimura Y. Nature. 1990;344:461–463. doi: 10.1038/344461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valcárcel J, Singh R, Zamore PD, Green MR. Nature. 1993;362:171–175. doi: 10.1038/362171a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Samuels ME, Bopp D, Colvin RA, Roscigno RF, Garcia-Blanco MA, Schedl P. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994;14:4975–4990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh R, Valcarcel J, Green MR. Science. 1995;268:1173–6. doi: 10.1126/science.7761834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Granadino B, Penalva LOF, Green MR, Valcárcel J, Sanchez L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997;94:7343–7348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin CH, Patton JG. RNA. 1995;1:234–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Norton PA, Hynes RO. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;195:215–21. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashiya M, Grabowski PJ. RNA. 1997;3:996–1015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Blanco MA, Jamison SF, Sharp PA. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1874–1886. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12a.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patton JG, Mayer SA, Tempst P, Nadal-Ginard B. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1237–1251. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghetti A, Piñol-Roma S, Michael WM, Morandi C, Dreyfuss G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:3671–3678. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.14.3671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valcárcel J, Gebauer F. Curr. Biol. 1997;7:R705–R708. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00361-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang Z, Zhang W, Rao Y, Wu JY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:9155–9160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L, Miura M, Bergeron L, Zhu H, Yuan J. Cell. 1994;78:739–750. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Noda M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1613–1626. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.14.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:69–72. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00602-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Troy CM, Stefanis L, Greene LA, Shelanski ML. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:1911–1918. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-06-01911.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haviv R, Lindenboim L, Yuan J, Stein R. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998;52:491–7. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980601)52:5<491::AID-JNR1>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar S, Kinoshita M, Dorstyn L, Noda M. Cell Death Differ. 1997;4:378–387. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bergeron L, Perez GI, Macdonald G, Shi L, Sun Y, Jurisicova A, Varmuza S, Latham KE, Flaws JA, Salter JC, Hara H, Moskowitz MA, Li E, Greenberg A, Tilly JL, Yuan J. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1304–1314. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.9.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Côté J, Dupuis S, Jiang ZH, Wu JY. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:938–943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031564098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Gene (Amst.) 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chabot B. In: RNA Processing. Hames D, Higgins S, editors. I. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1994. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dignam JD, Lebovitz RM, Roeder RG. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krainer AR, Maniatis T. Cell. 1985;42:725–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruskin B, Green MR. Science. 1985;229:135–140. doi: 10.1126/science.2990042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez I, Lin CH, McAfee JG, Patton JG. RNA. 1997;3:764–778. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Konarska MM, Sharp PA. Cell. 1986;46:845–855. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chabot B, Frappier D, La Branche H. Nucleic Acids Res. 1992;20:5197–5204. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.19.5197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Michaud S, Reed R. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2534–2546. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan RC, Black DL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:4667–4676. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eperon IC, Ireland DC, Smith RA, Mayeda A, Krainer AR. EMBO J. 1993;12:3607–3617. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06034.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chabot B, Blanchette M, Lapierre I, La Branche H. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997;17:1776–1786. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang Z, Cote J, Kwon JM, Goate AM, Wu JY. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:4036–4048. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4036-4048.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Caputi M, Casari G, Guenzi S, Tagliabue R, Sidoli A, Melo CA, Baralle FE. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.6.1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amendt BA, Si ZH, Stoltzfus CM. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:4606–4615. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Staffa A, Cochrane A. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:4597–4605. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carstens RP, McKeehan WL, Garcia-Blanco MA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:2205–2217. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kan JL, Green MR. Genes Dev. 1999;13:462–471. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Côté J, Simard MJ, Chabot B. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:2529–2537. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.12.2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gersappe A, Pintel DJ. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:364–375. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bourgeois CF, Popielarz M, Hildwein G, Stevenin J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:7347–7356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elrick LL, Humphrey MB, Cooper TA, Berget SM. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998;18:343–352. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blanchette M, Chabot B. EMBO J. 1999;18:1939–1952. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun H, Chasin LA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:6414–6425. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.17.6414-6425.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mulligan GJ, Guo W, Wormsley S, Helfman DM. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:25480–25487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norton PA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3854–3860. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.19.3854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gooding C, Roberts GC, Smith CW. RNA. 1998;4:85–100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grossman JS, Meyer MI, Wang YC, Mulligan GJ, Kobayashi R, Helfman DM. RNA. 1998;4:613–625. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298971448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Southby J, Gooding C, Smith CW. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999;19:2699–2711. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Carstens RP, Wagner EJ, Garcia-Blanco MA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:7388–7400. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7388-7400.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chan RC, Black DL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1995;15:6377–6385. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chou MY, Underwood JG, Nikolic J, Luu MH, Black DL. Mol. Cell. 2000;5:949–957. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Markovtsov V, Nikolic JM, Goldman JA, Turck CW, Chou MY, Black DL. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:7463–7479. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7463-7479.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Timchenko LT, Miller JW, Timchenko NA, DeVore DR, Datar KV, Lin L, Roberts R, Caskey CT, Swanson MS. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Philips AV, Timchenko LT, Cooper TA. Science. 1998;280:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang L, Liu W, Grabowski PJ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;254:522–528. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Polydorides AD, Okano HJ, Yang YY, Stefani G, Darnell RB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2000;97:6350–6355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110128397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]