Integrins control motile strategy through a Rho–cofilin pathway (original) (raw)

Abstract

During wound healing, angiogenesis, and tumor invasion, cells often change their expression profiles of fibronectin-binding integrins. Here, we show that β1 integrins promote random migration, whereas β3 integrins promote persistent migration in the same epithelial cell background. Adhesion to fibronectin by αvβ3 supports extensive actin cytoskeletal reorganization through the actin-severing protein cofilin, resulting in a single broad lamellipod with static cell–matrix adhesions at the leading edge. Adhesion by α5β1 instead leads to the phosphorylation/inactivation of cofilin, and these cells fail to polarize their cytoskeleton but extend thin protrusions containing highly dynamic cell–matrix adhesions in multiple directions. The activity of the small GTPase RhoA is particularly high in cells adhering by α5β1, and inhibition of Rho signaling causes a switch from a β1- to a β3-associated mode of migration, whereas increased Rho activity has the opposite effect. Thus, alterations in integrin expression profiles allow cells to modulate several critical aspects of the motile machinery through Rho GTPases.

Introduction

Fibronectin (FN) is an abundant component of the ECM expressed during embryonic development, angiogenesis, wound healing, and tumor invasion. Cell migration is critical for all these conditions and the motile cells often display altered expression of FN-binding integrins such as α5β1, αvβ3, and others (Mizejewski, 1999; Stupack and Cheresh, 2002; Watt, 2002). All these integrins bind the RGD motif in the central cell-binding domain of FN (Pankov and Yamada, 2002), but it is still unclear if and how they mediate specific cellular responses to FN. Here, we explored the possibility that they promote different aspects of cell migration and that switching integrins allows cells to modulate their motile response to FN.

The dynamic regulation of the F-actin network is crucial to cell migration and is mediated by multiple actin-polymerizing, -capping, -severing, and -cross-linking proteins (Pollard and Borisy, 2003; Ridley et al., 2003). The Arp2/3 complex and cofilin are involved in the generation of propulsive force at the leading edge: the severing activity of cofilin and the branching activity of Arp2/3 act in synergy to stimulate protrusion (DesMarais et al., 2004; Ghosh et al., 2004). Cofilin does not appear to be required for lamellipodia formation, per se, but it is required for directional migration with a single, broad lamellipod at the leading edge (Dawe et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2004; Mouneimne et al., 2004). Stabilization of lamellipodia occurs through integrin-mediated adhesion to the ECM. Integrins cluster in cell–matrix adhesions where they connect the ECM to the F-actin network via scaffolding proteins such as talin, vinculin, and paxillin. At the front of a migrating cell, the adhesions are static and act as traction sites, whereas they become more dynamic toward the rear (Ballestrem et al., 2001). Cell–matrix adhesions also recruit signaling intermediates such as FAK, Src, and ERK, which may regulate local dynamics during cell migration (Geiger et al., 2001).

The organization of the F-actin (as well as the microtubule) network and the formation of cell–matrix adhesions in response to extracellular cues are controlled by small GTPases of the Rho family (Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002). In their GTP-bound state Rho GTPases can activate multiple downstream effector pathways. Both Rac1 and RhoA have been reported to activate a pathway that results in the inhibition of cofilin through phosphorylation at Ser3 (Edwards et al., 1999; Maekawa et al., 1999), but Rac1 supports lamellipodia extension and formation of nascent adhesions, whereas RhoA stimulates stress fiber formation and maturation of cell–matrix adhesions (Rottner et al., 1999). In a migrating cell the activities of the different Rho GTPases and/or their effector pathways must be controlled in a temporal and spatial manner, but it is incompletely understood how this is brought about (Ridley et al., 2003).

Integrin expression profiles might affect the migratory response to FN through integrin-specific effects on the activities of Rho family GTPases. Integrin-mediated adhesion to FN stimulates Rac1 activation and membrane extension (Price et al., 1998; del Pozo et al., 2000), whereas it triggers an abrupt reduction in the levels of GTP-bound RhoA (Ren et al., 1999; Arthur et al., 2002). At later stages of cell spreading on FN, RhoA GTP levels increase through an unknown mechanism that supports further actin cytoskeletal rearrangement. In leukocytes and CHO cells, overexpression of αvβ3 has been linked to increased RhoA GTP levels (Miao et al., 2002; Butler et al., 2003), but using epithelial and fibroblastic cells derived from β1 knockout mice we have shown that β1 integrins are required to support RhoA activation (Danen et al., 2002).

We and others have also shown that cell migration is strongly inhibited when β1 integrins are absent (Gimond et al., 1999; Sakai et al., 1999; Raghavan et al., 2003). Here, we show that an increased expression of αvβ3 effectively stimulates migration of β1 null cells, arguing against a specific requirement for β1 integrins, by themselves, for migration. However, β1 and β3 integrins promote dramatically different modes of migration on FN. Lamellipodia formation, cell–matrix adhesion dynamics, and cofilin-mediated actin cytoskeletal polarization all are differently affected by β1 and β3 integrins. This involves the differential activation of Rho GTPases and ultimately affects the persistence of migration. Our findings demonstrate that the alterations in the expression of FN-binding integrins, as observed in vivo, can profoundly affect multiple parameters of cell migration through changes in the activity of Rho GTPases.

Results

Integrins control persistence of migration

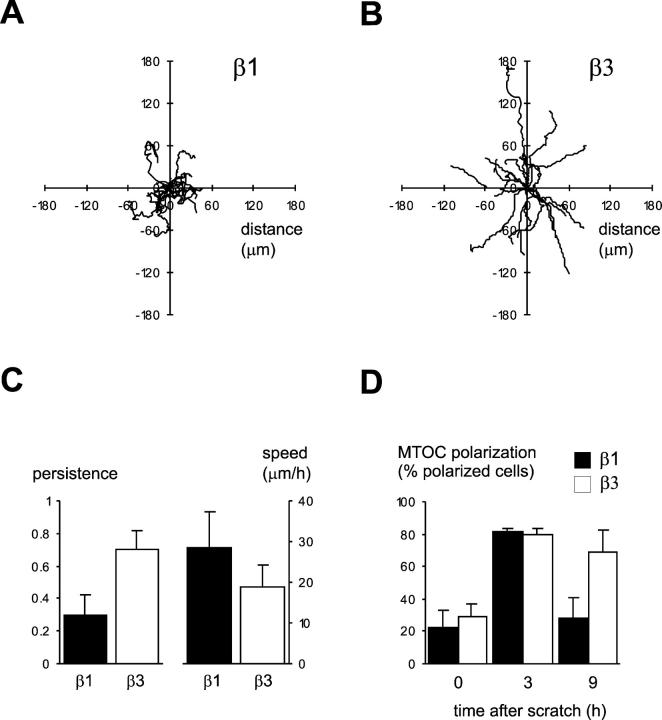

We have previously observed that β1 integrin–deficient epithelial GE11 cells hardly migrate (Gimond et al., 1999; Sakai et al., 1999; Raghavan et al., 2003). To test if increased levels of other FN-binding integrins could induce migration on FN, or whether specific functions of β1 integrins are essential, we compared the migratory properties of GE11 cells transduced with either β1 (GEβ1; these cells do not express αvβ3) or β3 cDNA (GEβ3; these cells lack β1 but express αvβ3 at high levels). GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells adhere with similar efficiency to the RGD region in the central cell binding domain of FN by α5β1 or αvβ3, respectively (Danen et al., 2002). In wounding assays GE11 cells hardly migrated while expression of β1 integrins induced migration on FN as expected. However, GEβ3 cells also migrated efficiently on FN, which argues against a unique requirement for β1 integrins in cell migration (Video 1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

Notably, the motile behavior in wounding assays differed dramatically for cells adhering by α5β1 or αvβ3: GEβ1 cells moved randomly as single cells extending protrusions in multiple directions, whereas GEβ3 cells moved as a sheet of cells that maintained directionality (Video 1). To rule out effects due to differences in cell–cell adhesion, the migration of sparsely seeded cells was analyzed. The velocity under these conditions was ∼25 μm/h for both cell types. However, similar to the results obtained in wounding assays, GEβ1 cells moved randomly whereas GEβ3 cells moved in a much more persistent fashion (Fig. 1 A–C; Video 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). To examine if the lack of directionality of GEβ1 cells in wounding assays was due to a defect in polarization, we analyzed if these cells responded to wounding by polarizing their microtubule-organizing center (MTOC) (Gotlieb et al., 1981). GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells at the wound edge polarized their MTOC with similar efficiency within 3 h after wounding (Fig. 1 D; Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1), indicating that GEβ1 cells could “sense” the wound and orient their MTOC accordingly. However, although GEβ3 cells maintained their polarized phenotype as they migrated into the wound area, MTOC polarity in the direction of the wound was lost in GEβ1 cells during this process (Fig. 1 D, 9 h).

Figure 1.

β1 and β3 integrins differentially affect motile behavior. (A and B) Migration tracks of GEβ1 (A) or GEβ3 cells (B) seeded sparsely on FN-coated coverslips and followed for 16 h. Shown are 20 cells obtained from three independent experiments. (C) Analysis of persistence (ratio of the direct distance from start point to end point divided by the total track distance) and speed of migrating GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells in sparse cultures. (D) Analysis of MTOC polarization in wounding assays with GEβ1 (filled bars) and GEβ3 cells (open bars) at the indicated time points after wounding of confluent monolayers on FN-coated coverslips. Mean ± SD of ∼100 cells analyzed in three independent assays is shown. See supplemental data for the accompanying videos and immunofluorescence images (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

For the above experiments, FN was used at 10 μg/ml. We tested if the migratory behavior of GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells was affected by the concentration of FN. Even though migration velocity decreased when lower concentrations of FN were coated, the pattern of migration (random vs. persistent) was not affected, indicating that differences in the FN binding affinity cannot explain the distinct modes of migration (unpublished data). This is in line with our previous observation that GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells adhere with similar kinetics to substrates coated with FN in concentrations ranging from 1–32 μg/ml (Danen et al., 2002).

Together, these findings demonstrate that in the same cellular context, β1 and β3 integrins promote distinct migratory strategies. Integrin αvβ3 supports a persistent lamellipodial mode of migration, whereas cells adhering by α5β1 do not maintain polarity and migrate randomly.

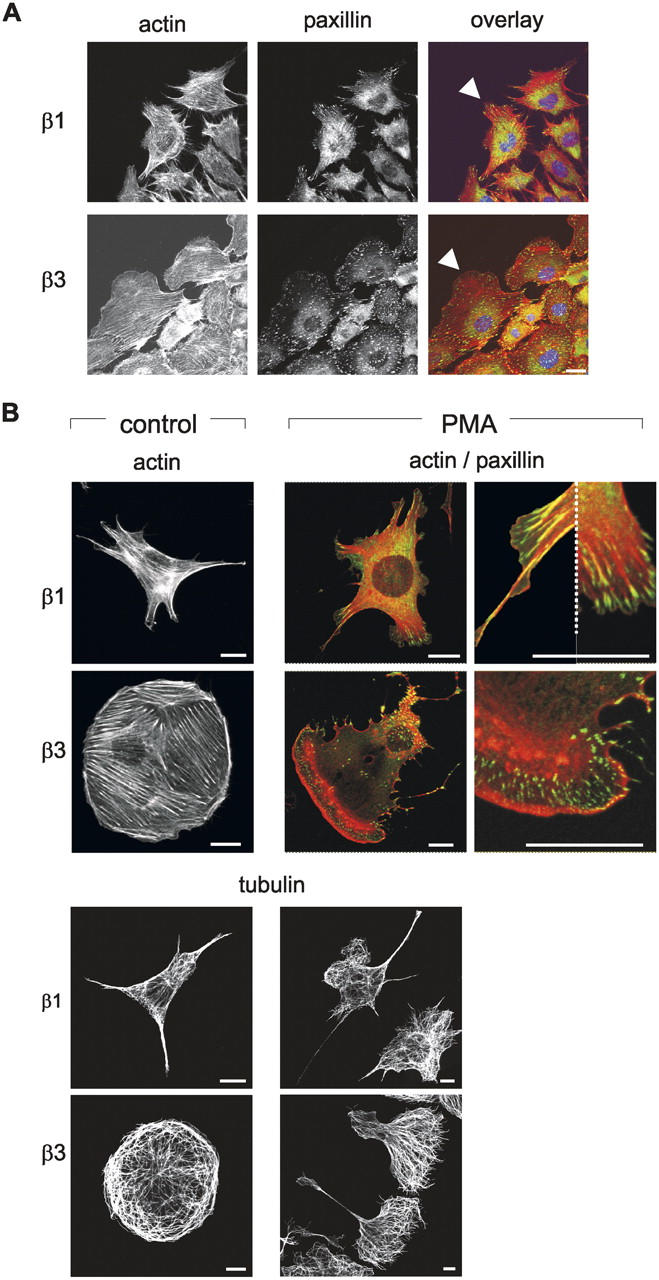

Integrin-specific regulation of cytoskeletal polarization and cofilin activity

We next tested if differences in actin cytoskeletal polarization could explain the maintenance of directionality in GEβ3 versus its loss in GEβ1 cells. Indeed, GEβ3 cells formed broad lamellipodia at the leading edge that were devoid of stress fibers and contained numerous small cell–matrix adhesions, whereas no such remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton was observed in GEβ1 cells: these cells extended long, thin membrane protrusions with actin stress fibers ending at elongated cell–matrix adhesions (Fig. 2 A). To analyze whether GEβ1 cells intrinsically lacked the ability to undergo extensive actin cytoskeletal remodeling, we treated the GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells with EGF, HGF, and the phorbol ester PMA, which is known to cause a reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (Schliwa et al., 1984). Although EGF did not noticeably affect the morphology of either cell type, HGF induced ruffling in GEβ3 cells but not in GEβ1 cells (unpublished data). Moreover, although GEβ3 cells responded to PMA treatment with a dramatic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and formation of a large lamellipod that was devoid of actin stress fibers, PMA hardly affected the actin cytoskeleton in GEβ1 cells (Fig. 2 B). It has been reported that the distribution of microtubules is changed to conform to the altered cellular shape upon PMA stimulation, but that the microtubule cytoskeleton is not functionally implicated in the morphological response to PMA (Schliwa et al., 1984). Indeed, GEβ3 (but not GEβ1) cells also underwent a dramatic reorganization of their microtubule cytoskeleton in response to PMA (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

β1 and β3 integrins differentially regulate actin cytoskeletal reorganization. (A) GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells, stably expressing GFP-paxillin, were plated overnight on FN-coated coverslips, confluent monolayers were wounded with a micropipette tip, and preparations were fixed and permeabilized after 5 h. Organization of the actin cytoskeleton and localization of paxillin is shown as indicated. Arrowheads indicate protrusions of cells moving into the wounded area. Bar, 10 μm. (B) GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells were plated on FN-coated coverslips for 4 h and fixed and permeabilized either immediately (control) or after stimulation with PMA for 1 h as indicated. Single staining for F-actin, double staining for F-actin (red) and paxillin (green), or single staining for α-tubulin are shown as indicated with details of membrane protrusions shown at higher magnification at the far right. Dotted line separates two different protrusions. Bars, 5 μm.

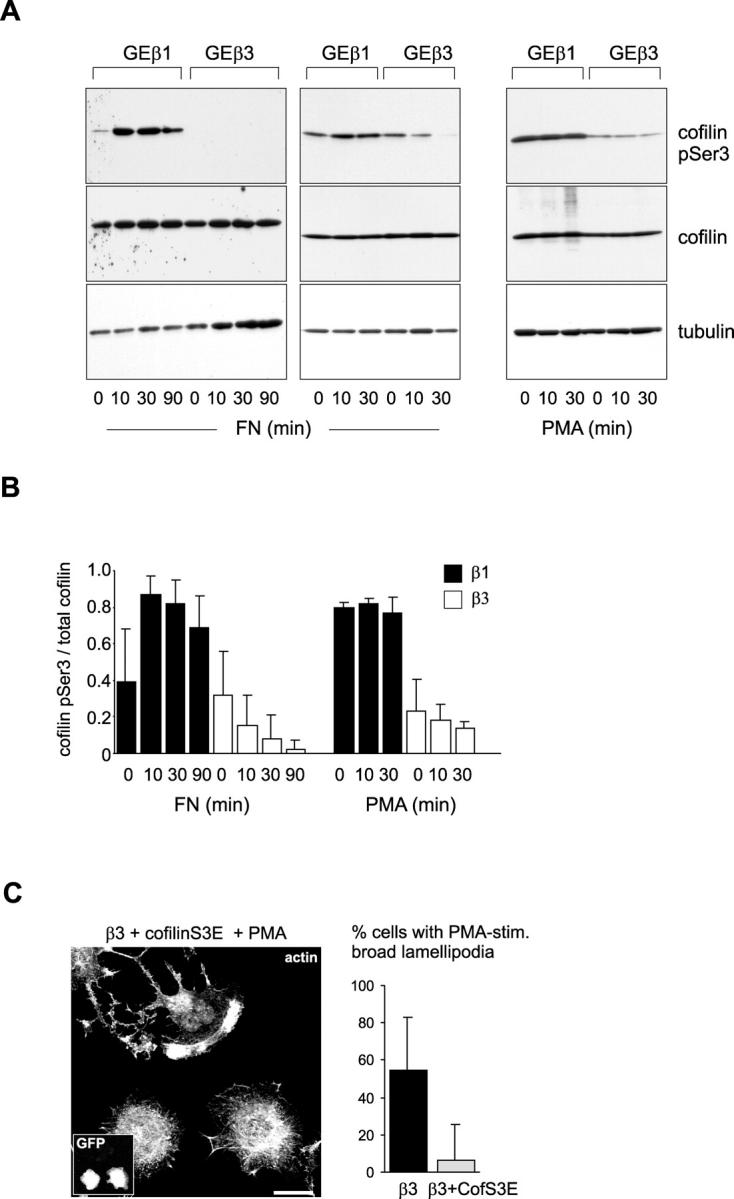

Cofilin has been implicated in cytoskeletal polarization and directional migration (Dawe et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2004; Mouneimne et al., 2004). We tested whether the observed differences in actin cytoskeletal reorganization in wounded or PMA-treated GEβ1 and GEβ3 cultures were related to differences in cofilin activity. Phospho-cofilin levels in serum-starved, suspended cells varied between experiments (Fig. 3 A; compare time “0” in left and middle). Nevertheless, irrespective of the phosphorylation status before plating, the relative amount of cofilin phosphorylated on Ser3 in cells attached to FN was much higher in GEβ1 than in GEβ3 cells, indicating that FN-adhered GEβ3 cells contained a larger pool of nonphosphorylated, active cofilin (Fig. 3 A, left and middle; Fig. 3 B, left). Notably, in line with the observation that PMA hardly affected the morphology of GEβ1 cells, PMA treatment did not affect the cofilin phosphorylation status (i.e., no decrease in cofilin Ser3 phosphorylation was observed in GEβ1 cells treated with PMA; Fig. 3, A and B, right). Finally, to analyze if the difference in cofilin activity could explain the differences in actin reorganization, we expressed dominant-active and -inactive cofilin mutants in GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells, respectively. Expression of a GFP-tagged active, nonphosphorylatable cofilinS3A mutant in GEβ1 cells or expression of an inactive, phospho-mimetic cofilinS3E mutant in GEβ3 cells had no apparent effect on cell–matrix adhesion distribution or actin cytoskeletal organization in cells plated for 2–4 h on FN (unpublished data). GEβ1 cells transfected with cofilinS3A also remained unable to reorganize their actin cytoskeleton in response to PMA (unpublished data). However, expression of the cofilinS3E mutant in GEβ3 significantly interfered with the formation of broad lamellipodia in response to PMA, indicating that cofilin activity is required for the actin cytoskeletal reorganization (Fig. 3 C).

Figure 3.

β1 and β3 integrins differentially regulate cofilin pSer3 levels. (A) GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells were serum starved overnight, trypsinized, incubated in suspension for 30–60 min, and plated on FN for the indicated times (left and middle) or followed by plating on FN for 90 min and subsequent treatment with PMA for the indicated times (right). Western blot analysis of total lysates with the indicated antibodies is shown. (B) Quantification based on four (left) or two (right) experiments such as shown in A. Mean ± SD of relative cofilin Ser3 phosphorylation in GEβ1 (filled bars) and GEβ3 cells (open bars) is shown. (C) GEβ3 cells transiently transfected with a cDNA encoding GFP-cofilinS3E were plated on FN-coated coverslips for 4 h and fixed and permeabilized after stimulation with PMA for 1 h. Organization of the actin cytoskeleton is shown. Inset shows GFP signal. Note that the upper, nontransfected cell generates a typical broad lamellipod whereas transfected cells do not. Bar, 10 μm. Quantification of the percentage of cells responding to PMA treatment by formation of broad lamellipodia is depicted in the graph at the right. Mean ± SD of ∼100 cells analyzed in two independent assays is shown.

Together, these results show (1) that adhesion by β3 but not β1 integrins supports extensive actin cytoskeletal reorganization and polarization in response to wounding, HGF, or phorbol ester; and (2) that cofilin activity is regulated in an integrin-specific fashion by adhesion to FN and is a prerequisite for such actin reorganization to occur.

Integrin-specific regulation of cell–matrix adhesion dynamics

In addition to actin cytoskeletal polarization, persistent migration also requires cell–matrix adhesions at the leading edge to be sufficiently static to stabilize the lamellipod and generate traction forces. Therefore, we analyzed if differences in the dynamics of cell–matrix adhesions in GEβ1 and GEβ3 could explain the distinct migratory behavior of these cells. Time lapse confocal imaging of GFP-paxillin in migrating GEβ1 cells showed cell–matrix adhesions sliding away from the main cell body in membrane protrusions that extended in multiple directions (Video 3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). These extensions were often short-lived, and their collapse was accompanied by a rapid retraction of the adhesions. By contrast, cell–matrix adhesions at the leading edge of GEβ3 cells were relatively inert, whereas large adhesions were observed to slide inwards at the rear. The same phenomenon could be observed during cell spreading on FN: adhesions in GEβ1 cells were seen sliding outwards, whereas adhesions in GEβ3 did not obviously move. Rather, new adhesions accumulated in GEβ3 cells while existing adhesions remained intact (Fig. 4 A; Video 4). The apparent sliding of adhesions in GEβ1 cells was correlated with a relatively fast turnover rate (within 3–4 min) as compared with that of adhesions in GEβ3 cells (stable for at least 10 min) (Fig. 4 A and unpublished data).

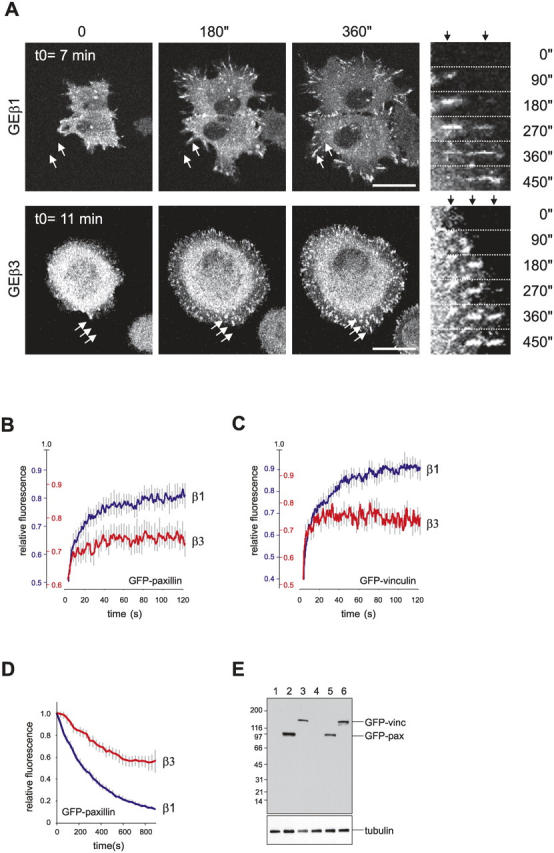

Figure 4.

β1 and β3 integrins differentially regulate distribution and dynamics of cell–matrix adhesions. (A) Images of GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells stably expressing GFP-paxillin were taken at the cell–substrate contact area every 15 s after plating on FN-coated coverslips. The time after plating of the first image is indicated (t0). Bars, 10 μm. The right-most panel shows detailed images of the region indicated by arrows at the indicated time points. See supplemental data for the accompanying videos. (B and C) FRAP analysis of GFP-paxillin (B) and GFP-vinculin (C) in cell–matrix adhesions of GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells. Mean ± SEM of three independent experiments, in which at least six cells per experiment were analyzed, is shown. (D) FLIP analysis of GFP-paxillin in cell–matrix adhesions of GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells. Mean ± SEM of four independent experiments, in which 10 adhesions per cell in at least 3 cells per experiment were analyzed, is shown. (E) Western blot using GFP antibody and α-tubulin–loading control antibody on GEβ1 (lanes 1–3) and GEβ3 cells (lanes 4–6) stably expressing GFP-paxillin (lanes 2 and 5), GFP-vinculin (lanes 3 and 6), or controls (lanes 1 and 4). Molecular weights are indicated at the left. See supplemental data for example pictures of FLIP experiments (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

These findings indicate that the type of integrin involved in the adhesion to FN strongly affects cell–matrix adhesion dynamics. To further test this, we analyzed the dynamics of two different cell–matrix adhesion components—paxillin and vinculin—in more detail by performing fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) and fluorescence loss in photobleaching (FLIP) experiments. Strikingly, even in stationary, fully spread cells, the dynamics of GFP-paxillin and GFP-vinculin in adhesions of GEβ1 cells as measured by FRAP were significantly higher than those in adhesions formed by GEβ3 cells (P = 0.0003 and P < 0.0001, respectively; Fig. 4, B and C). These findings were confirmed using FLIP as an alternative method of analysis: loss of fluorescence from cell–matrix adhesions in GEβ1 cells expressing GFP-paxillin was significantly faster (P < 0.0001) than that in GEβ3 cells (time required for a 50% reduction in fluorescence, τ = 5.6 min in GEβ1 vs. τ = 21.3 min in GEβ3) (Fig. 4 D, Fig. 5 C; Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). The results were not affected by differences in expression levels or degradation of the GFP fusion constructs as shown by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4 E).

Figure 5.

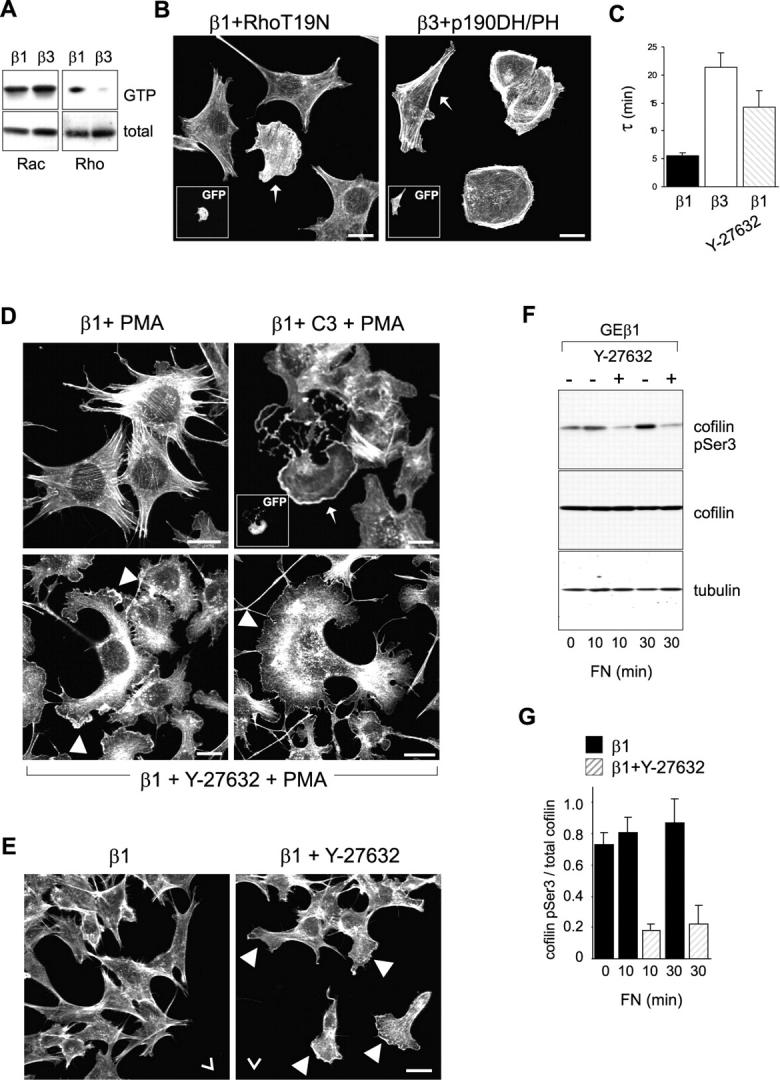

Inhibition of Rho signaling in GEβ1 cells. (A) Rac and Rho activity assay in GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells. (B) GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells transiently transfected with the indicated expression plasmids in combination with GFP cDNA as a transfection marker (insets) were seeded on FN-coated coverslips 24 h after transfection for 12 h and were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin. Arrows indicate transfected cells. Bars, 10 μm. (C) Analysis of GFP-paxillin dynamics in cell–matrix adhesions of GEβ1, GEβ3, and Y27632-treated GEβ1 cells. Shown is the halftime of loss of fluorescence (τ) ± SEM calculated from FLIP experiments such as depicted in Fig. 4 D. (D) Control or C3-transfected GEβ1 cells (indicated by GFP; inset and arrow) were plated overnight on FN-coated coverslips and stimulated with PMA for 1 h in the absence or presence of Y27632 as indicated. Preparations were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin. Filled arrowheads indicate Y27632-induced membrane ruffles/lamellipodia. Bars, 5 μm. (E) GEβ1 cells were plated overnight on FN-coated coverslips, confluent monolayers were wounded with a micropipette tip, and preparations were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin after 5 h incubation in the absence or presence of Y27632. Open arrowheads indicate the direction of the wound; filled arrowheads indicate Y27632-induced protrusions of cells moving into the wounded area. Bar, 10 μm. (F) GEβ1 cells were plated on FN-coated coverslips for the indicated times in the absence or presence of Y27632 as indicated. Western blot analysis of total lysates with the indicated antibodies is shown. (G) Mean ± SD of relative cofilin Ser3 phosphorylation determined from two individual experiments such as depicted in F.

Finally, we investigated the possibility that the different dynamics of cell–matrix adhesions were due to the different effects on cofilin activity of these two integrins. Therefore, we transiently expressed a dsRed vector alone, or in combination with HA-tagged active cofilinS3A or inactive cofilinS3D in GFP-paxillin–transduced GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells, respectively, and measured cell–matrix adhesion dynamics by FLIP analysis. However, in line with the fact that expression of these cofilin mutants did not significantly alter cell–matrix adhesion distribution in cells plated for 2–4 h on FN, they did not alter their dynamics in this assay (Fig. S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

Together, these findings show that cell–matrix adhesions formed on FN in stationary as well as in spreading or migrating cells adhering by α5β1 are highly dynamic, whereas those formed by cells adhering by αvβ3 are relatively static.

Inhibition of Rho signaling induces a switch from β1- to β3-associated behavior

We previously showed that RhoA activity is supported by β1 but not by β3 integrins, whereas Rac-GTP levels are similar (Fig. 5 A; Danen et al., 2002), and we examined whether this difference might explain the distinct modes of cell migration supported by these integrins. Expression of a dominant-inhibitory RhoA mutant (RhoT19N) or expression of the Rho inhibitor C3 toxin in GEβ1 cells induced a conversion to more circularly spread cells, reminiscent of a GEβ3-like phenotype (Fig. 5 B; Fig. S4, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). Vice versa, expression of an activated mutant of RhoA (RhoAQ63L) or the catalytic DH/PH domain of p190RhoGEF in GEβ3 cells caused a switch toward a GEβ1-like phenotype, though cells expressing these constructs at too high levels were unable to spread on FN at all (Fig. 5 B; Fig. S4). Inhibition of signaling downstream from Rho using the Y27632 Rho kinase inhibitor caused extension of extremely long protrusions in line with an important function for Rho kinase in tail retraction. However, Y27632-treated GEβ1 cells were also observed to switch to a GEβ3-like morphology and a β3-like migration pattern when seeded sparsely, a phenomenon that was never observed in nontreated GEβ1 cells (Video 5, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). In such cells the mobility of GFP-paxillin in cell–matrix adhesions was also significantly decreased, with a τ-value that became almost as high as that observed in GEβ3 cells (Fig. 5 C). Inhibition of RhoA or of its downstream effector Rho kinase also restored the ability of GEβ1 cells to reorganize their actin cytoskeleton in response to PMA treatment or wounding: expression of C3 toxin or treatment with Y27632 supported the generation of broad lamellipodia in GEβ1 cells, similar to those seen in GEβ3 cells (Fig. 5, D and E).

Because cofilin activity was regulated in an integrin-specific fashion and was required for the formation of broad lamellipodia in GEβ3 cells (Fig. 3), we investigated if the high level of phosphorylation of cofilin on Ser3 in GEβ1 cells was also due to the relatively high activity of the Rho/Rho kinase pathway in GEβ1. Indeed, inhibition of Rho kinase caused a strong and significant decrease in cofilin pSer3 levels to a level normally seen in GEβ3 (Fig. 5, F and G).

Together, these findings show that the differences in lamellipodia formation, cell–matrix adhesion dynamics, and cofilin-mediated actin cytoskeletal polarization observed between cells adhering to FN by β1 or β3 integrins are due to the difference in Rho signaling.

Rac1 activation causes a partial conversion from β1- to β3-associated behavior

Extensive cross talk takes place between effector pathways downstream of Rho and Rac. In GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells, the balance between Rho and Rac activities differs due to the higher amounts of Rho-GTP in GEβ1 cells (Fig. 5 A). To test if this balance, rather than RhoA activity by itself, was responsible for the different modes of migration of GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells, we transiently expressed an activated mutant of Rac1 in GEβ1 cells. Expression of RacQ61L caused a conversion from a β1- to a β3-associated morphology (Fig. 6 A). Moreover, the conversion to a GEβ3-like morphology observed in GEβ1 cells transiently expressing RacQ61L was accompanied by a decrease in the dynamics of GFP-paxillin in their cell–matrix adhesions to a level that became indistinguishable from that observed in GEβ3 (Fig. 6 B).

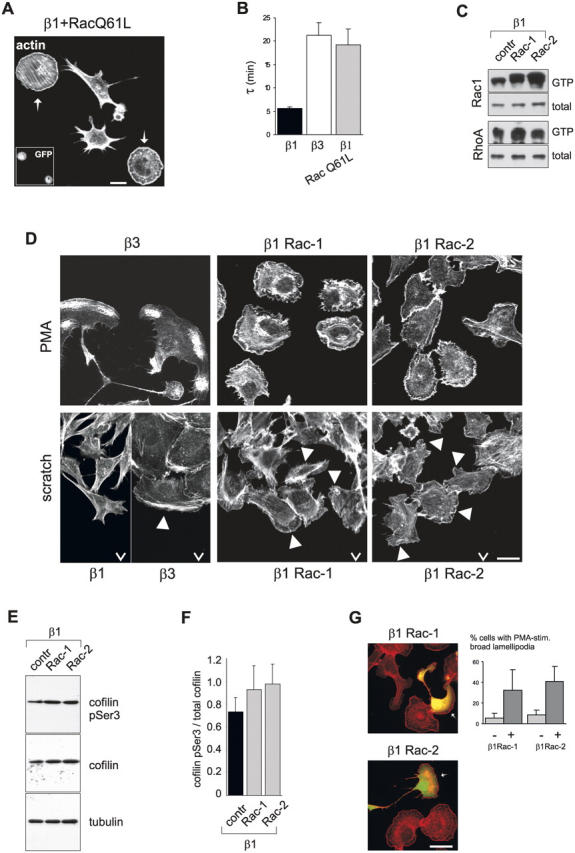

Figure 6.

Expression of activated Rac in GEβ1 cells. (A) GEβ1 cells transiently transfected with RacQ61L in combination with GFP cDNA as a transfection marker (inset) were seeded on FN-coated coverslips 24 h after transfection for 12 h, and were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin. Arrows indicate transfected cells. Bar, 10 μm. (B) Analysis of GFP-paxillin dynamics in cell–matrix adhesions of GEβ1, GEβ3, and GEβ1 cells transiently transfected with RacQ61L in combination with dsRed cDNA as a transfection marker. Shown is the halftime of loss of fluorescence (τ) ± SEM calculated from FLIP experiments such as depicted in Fig. 4 D. (C) Rac1 and RhoA activity assay in control GEβ1 cells and two stable GEβ1RacQ61L clones. (D) GEβ1, GEβ3, and two GEβ1RacQ61L clones were plated on FN-coated coverslips either sparsely for 2 h followed by treatment with PMA for 1 h (top) or confluently overnight followed by wounding and incubation for an additional 5 h (bottom). Preparations were fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin. Open arrowheads indicate the direction of the wound; filled arrowheads indicate lamellipodia. Bar, 10 μm. Note that GEβ1RacQ61L cells do not show extensive actin cytoskeletal remodeling such as seen in GEβ3 besides increased ruffling in response to PMA or wounding. (E) Control GEβ1 cells and two GEβ1RacQ61L clones were plated on FN-coated coverslips for 1 h. Western blot analysis of total lysates with the indicated antibodies is shown. (F) Mean ± SD of relative cofilin Ser3 phosphorylation determined from two individual experiments such as depicted in E. (G) GEβ1RacQ61L clones were transiently transfected with a plasmid encoding GFP-tagged dominant-active cofilinS3A 24 h before plating on FN-coated dishes. After 2 h of adhesion, cells were stimulated with PMA for 1 h, fixed, permeabilized, and stained for F-actin. Arrows indicate transfected cells. Note ruffling in nontransfected cells versus extensive cytoskeletal reorganization in transfected cells. Bar, 10 μm. Quantification of the percentage of cells responding to PMA treatment by formation of broad lamellipodia is depicted in the graph. Mean ± SD of ∼100 cells analyzed in two independent assays is shown.

Next, multiple stable GEβ1RacQ61L clones were generated to test if increased Rac1 activity also caused a conversion to a β3-associated pattern of migration. These clones had a similar, round morphology as GEβ1 cells transiently expressing RacQ61L (unpublished data) and Rac activity was strongly increased without a concomitant decrease in Rho GTP levels (Fig. 6 C). However, despite extensive membrane ruffling in response to PMA treatment or wounding, the actin cytoskeleton in GEβ1RacQ61L cells was not grossly reorganized as in GEβ3 cells and they failed to polarize (Fig. 6 D). Instead, in wounding assays GEβ1RacQ61L cells moved inefficiently and in a random fashion (unpublished data), whereas in sparse cultures they hardly moved at all (Video 6, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

In agreement with the notion that cofilin activity is implicated in actin cytoskeletal polarization (Fig. 3), phosphorylation of cofilin on Ser3 was not reduced in GEβ1 cells expressing RacQ61L (Fig. 6, E and F). This suggested that these cells lacked sufficient cofilin activity to polarize their actin cytoskeleton. Therefore, we tested if expression of the activated cofilinS3A mutant could induce polarization in GEβ1RacQ61L cells. Indeed, GEβ1 cells expressing both RacQ61L and cofilinS3A underwent a dramatic reorganization of their actin cytoskeleton in response to PMA. In some cells this resulted in a distorted shape, but many others showed a phenotype that was indistinguishable from GEβ3 (Fig. 6 G). Moreover, sparsely seeded GEβ1RacQ61L cells transfected with cofilinS3A were considerably more dynamic and initiated membrane extensions at the leading edge that were highly reminiscent of GEβ3 cells. However, this did not result in efficient lamellipodial migration but caused cellular disruption, most likely due to unusually high levels of Rac and cofilin activity throughout the entire cell (Video 7, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

These findings demonstrate that increased Rac activity, although causing enhanced membrane ruffling and cell–matrix adhesion stability, is unable to support polarization and directional migration in cells adhering to FN by α5β1. This appears to be at least partly due to the fact that it does not stimulate an increase in active cofilin levels.

Discussion

Migrating cells establish a polarized morphology with a single, broad lamellipod at the front that contains an actin cytoskeletal meshwork associated with many static cell–matrix adhesions, whereas at the rear F-actin stress fibers connect with large, sliding adhesions (Ballestrem et al., 2001; Ridley et al., 2003). Here, we demonstrate that integrin-specific regulation of Rho GTPases controls the cellular machinery that is required for cells to adopt such a polarized directional migration pattern.

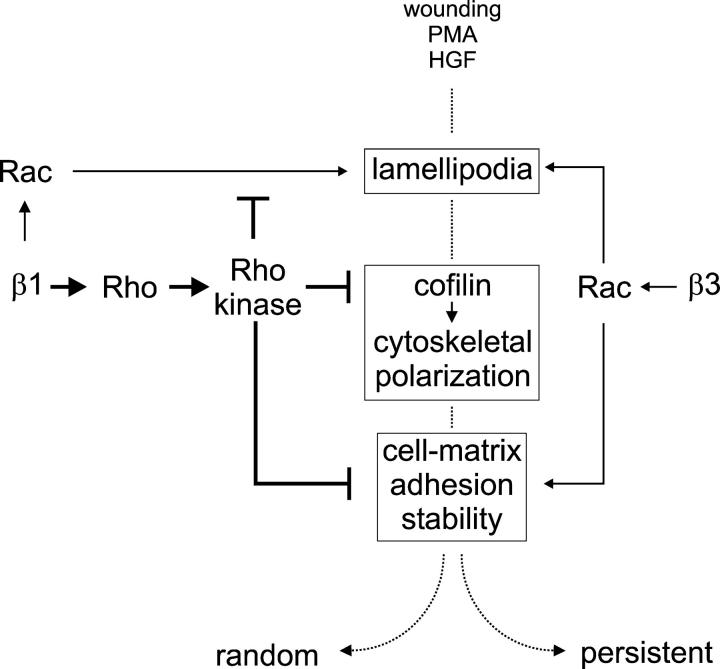

We show that αvβ3-mediated adhesion to FN supports high cofilin activity, which plays a permissive role in the F-actin cytoskeletal reorganization induced by wounding or by other stimuli such as PMA treatment. This allows for the cytoskeletal polarization observed in persistently migrating cells, with a single broad lamellipod at the leading edge under which cell–matrix adhesions are relatively static. By contrast, cofilin activity is low, polarization does not occur, and cell–matrix adhesions are highly dynamic in cells adhering by α5β1, leading to a random mode of migration. We show that integrin-specific regulation of Rho GTPases underlies the distinct modes of migration: inhibition of Rho signaling promotes membrane ruffling, cofilin-mediated actin cytoskeletal polarization, and cell–matrix adhesion stability and hence, can cause a conversion from β1- to β3-associated migratory behavior. Increased Rac activity promotes membrane ruffling but does not increase cofilin activity, and therefore causes only a partial conversion from β1- to β3-like migration (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

Model for the control of cell migration by integrin-specific regulation of Rho GTPases. Adhesion by β1 integrins promotes strong Rho/Rho kinase signaling. This counteracts three important parameters of persistent cell migration: (1) Rac-mediated lamellipodia formation; (2) development of static cell–matrix adhesions; and (3) cofilin-mediated actin cytoskeletal reorganization. As a result, β1 integrins promote a random mode of migration. Inhibition of Rho/Rho kinase signaling relieves the suppression of all three aspects and causes a switch from β1- to β3-associated behavior. Conversely, increased Rho signaling in cells adhering by αvβ3 triggers a conversion to β1-associated behavior. Increased Rac signaling can also stimulate a partial conversion from β1- to β3-associated behavior with increased lamellipodia formation and stabilization of cell–matrix adhesions. However, this does not lead to increased cofilin activity and hence, does not stimulate persistence.

β1 versus β3 integrins in cell migration

We find that β1 and β3 integrins promote different modes of migration, but neither of them is essential. It has been shown that β1 integrin–deficient keratinocytes, which express αvβ6 at high levels, are extremely static due to an inability to efficiently remodel their integrin–actin cytoskeletal network (Raghavan et al., 2003). The β1-deficient epithelial cells used in our study also hardly migrate, but this defect is rescued by an increased expression of αvβ3, arguing against a requirement of β1 integrins by themselves for cell migration. Besides other differences that may exist between the two cell types used in these studies, αvβ3 and αvβ6 might differently regulate actin dynamics and migration in the absence of β1.

Rather than β1 integrins being required for migration in general, our findings suggest that β1 integrins contribute to specific aspects of cell migration, which may be important under certain conditions in vivo. In three-dimensional substrata, cells can adopt a persistent mode of migration with a pseudopod (the three-dimensional variant of a lamellipod) at the leading edge attaching to the ECM, but, alternatively, they can move randomly, undergoing amoeboid shape changes (Sahai and Marshall, 2003; Wolf et al., 2003). We find that high levels of RhoA activity are associated with random migration in two dimensions, and the work by Sahai and Marshall (2003) demonstrates that RhoA activity is associated with the random amoeboid migration in three dimensions. Thus, in both situations RhoA activity stimulates a pattern of migration in which cells often change direction. Our present findings connect β1 integrins to such a RhoA-mediated random mode of migration. In agreement with this, silencing of the gene encoding the Fos family member Fra-1 in colon carcinoma cells leads to increased β1 integrin–mediated RhoA activation and suppression of Rac-mediated polarized lamellipodia extension (Vial et al., 2003). Clearly, for optimal migration, the balance between Rho and Rac activities must be tightly regulated. For instance, we show that expression of constitutively activated Rac does not necessarily support persistence of migration, due to the excessive formation of lamellipodia in multiple directions. Based on our work and the above-mentioned studies, we propose that β1 integrins support RhoA activity, which is associated with a random mode of migration. Binding to FN by αvβ3 instead is associated with low levels of RhoA activity, shifting the balance to Rac-mediated, highly polarized, persistent migration. In vivo, modulation of the expression profiles of these integrins may thus allow cells to optimize their mode of migration.

Regulation of cofilin activity

The severing activity of cofilin and the branching activity of Arp2/3 act in synergy to drive the extension of lamellipodia (Bamburg, 1999; Pollard and Borisy, 2003; Ghosh et al., 2004). Recently, cofilin activity has been reported to be particularly important for the maintenance of a polarized cytoskeleton and thus for directional cell migration (Dawe et al., 2003; Ghosh et al., 2004; Mouneimne et al., 2004). In accord with this, we show that the persistent mode of migration of cells bound to FN by αvβ3 is associated with relatively high levels of cofilin activity. Adhesion by α5β1 instead stimulates an increase in cofilin Ser3 phosphorylation and supports random migration.

Rho, Rac, and Cdc42, via their effectors (Rho kinase or PAK), can each stimulate the activity of LIM kinase that inactivates cofilin by phosphorylation at Ser3 (Agnew et al., 1995; Arber et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998; Maekawa et al., 1999). In the cells used for our study, the Rho/Rho kinase pathway is responsible for cofilin phosphorylation. Adhesion to FN by α5β1 causes high levels of Rho/Rho kinase–mediated cofilin phosphorylation, whereas adhesion by αvβ3 supports low levels of RhoA activity, leaving a relatively large proportion of cofilin in the nonphosphorylated, active form. The level of Rac activity in GEβ3 or in Y27632-treated GEβ1 cells is apparently too low to cause high levels of cofilin phosphorylation. One explanation for our findings would be increased Rho kinase–mediated activation of LIM kinase in GEβ1 cells. However, we were unable to detect an increase in LIM kinase phosphorylation in GEβ1 cells versus GEβ3 cells (unpublished data). An alternative explanation would be that the levels or activity of Slingshot, the cofilin phosphatase (Niwa et al., 2002), are differentially affected, but this remains to be examined.

Regulation of cell–matrix adhesion dynamics

We find that the dynamic behavior of cell–matrix adhesions is strongly affected by their integrin composition. Adhesion to FN by either α5β1 or αvβ3 occurs with similar efficiency and kinetics. Nevertheless, adhesions containing α5β1 appear to be much more dynamic than those containing αvβ3, as indicated by the differences in the mobile fraction of paxillin and vinculin, both in motile and fully spread, nonmotile cells. Others have shown that adhesions at the leading edge of migrating cells (most likely containing a mix of various integrins) are relatively static, whereas those at the trailing edge have a high turnover rate and slide inwards (Ballestrem et al., 2001). It has also been reported that the active form of αvβ3 localizes preferentially at the edges of lamellipodia through a Rac-dependent mechanism (Kiosses et al., 2001). Moreover, local concentrations of Rac and coupling of GTP-Rac to downstream effectors were found to be increased in pseudopodia and lamellipodia (Cho and Klemke, 2002). Based on these reports and our current finding that expression of Rac1Q61L or treatment with Y27632 causes a decrease in the dynamics of cell–matrix adhesions in GEβ1 cells to levels similar to those in GEβ3 cells, we propose that the activated αvβ3 integrins found in lamellipodia may locally promote Rac activity and increased stability of cell–matrix adhesions, which would contribute to persistence of migration.

Little is known about the molecular mechanism involved in the assembly and disassembly of cell–matrix adhesions. The tyrosine kinases Src and FAK and the adaptor protein p130Cas are present in cell–matrix adhesions and have been implicated in their turnover (Ilic et al., 1995; Fincham and Frame, 1998; Webb et al., 2004). We have not observed any striking differences in the localization or phosphorylation of these proteins except for a delayed phosphorylation of FAK at the auto-phosphorylation site, Y397, in GEβ3 cells, which may contribute to the decreased adhesion turnover rates observed in these cells (Danen et al., 2002 and unpublished data). Alternative mechanisms may involve different localization and/or activation of PTP-PEST or SHP-2 because mouse embryonic fibroblasts deficient in these phosphatases develop abnormally high numbers of cell–matrix adhesions and their migration is impaired (Yu et al., 1998; Angers-Loustau et al., 1999). Finally, local ERK-mediated activation of myosin light-chain kinase as well as cleavage of the cell–matrix adhesion constituent, talin, by the calcium-dependent protease calpain have been proposed to contribute to cell–matrix adhesion dynamics (Franco et al., 2004; Webb et al., 2004). Future studies should clarify how all these events are affected by integrin-regulated Rho GTPase activities.

In conclusion, our study provides evidence that the differential modulation of Rho GTPases by α5β1 and αvβ3 affects three important parameters of cell migration: lamellipodia formation, cell–matrix adhesion dynamics, and cofilin-mediated actin cytoskeletal polarization. As a result, these integrins promote distinct modes of migration, with β1 integrins supporting random and β3 integrins promoting persistent migration. Based on these findings, we propose that the alterations in the expression profiles of FN-binding integrins as observed during wound healing, angiogenesis, and cancer metastasis allow cells to adopt a mode of migration that fits the local conditions.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, retroviral transductions, and cDNA transfections

GE11 β1-deficient epithelial cells were provided by Dr. Cord Brakebusch and Dr. Reinhard Fässler (Max Planck Institute, Martinsried, Germany) and have been described previously (Gimond et al., 1999). GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells were generated by retroviral expression of the β1 or the β3 integrin subunit, respectively, in GE11 cells, followed by FACS sorting (Danen et al., 2002). Expression levels of β1 and β3 integrins in these lines are shown in Fig. S5 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1). Cells were cultured in DME supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics.

The cDNAs encoding GFP paxillin and GFP vinculin (provided by Dr. Kenneth Yamada; National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) were cloned into the LZRS-neo bicistronic retroviral vector, and transfected to ecotrophic packaging cells to generate virus-containing culture supernatants. Subsequently, GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells were transduced and selected for stable expression of the GFP fusion proteins in cell–matrix adhesions.

Expression plasmids encoding C3 toxin, RhoAT19N, Rac1Q61L, and RhoAQ63L were provided by Dr. Sylvio Gutkind (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD), GFP-tagged cofilin expression constructs were provided by Dr. James Bamburg (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO; Agnew et al., 1995), HA-tagged cofilin expression constructs were from Dr. Kenji Moriyama (Moriyama et al., 1996; Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo, Japan) and the p190RhoGEFDH/PH expression plasmid was a gift from Dr. Wouter Moolenaar (Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands). For transient expression of these cDNAs, transfections were performed using the Effectene kit from QIAGEN according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Random migration analysis

GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells were plated sparsely (3 × 104 cells) on 24-mm glass coverslips coated with FN. Human plasma FN was purified as described previously (Danen et al., 2000) and used at 10 μg/ml in PBS, a concentration at which GEβ1 and GEβ3 cells adhere with identical efficiency (Danen et al., 2002). 3 h later, coverslips were incubated for 2 h with 10 mg/ml mitomycin-C (Sigma-Aldrich) to inhibit cell division, washed, and incubated overnight in culture medium covered with mineral oil at 37°C and 5% CO2. A 10× dry lens objective was used and phase-contrast images were taken every 15 min on a Widefield CCD system (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.); tracks of individual cells were analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The migration speed was calculated as [total path length (μm)/time (hour)] and the persistence of migration was calculated as [net displacement (μm)/total path length (μm)].

Analysis of migration and polarization in wounding assays

GE11, GEβ1, or GEβ3 cells were plated overnight at high density (2 × 105 cells) on 24-mm glass coverslips coated with FN. Confluent cultures were wounded using a blue pipette tip, washed, and incubated with fresh culture medium. A 10× dry lens was used and phase contrast images were taken every 15 min on a Widefield CCD system; videos were generated using ImageJ software.

For the analysis of MTOC polarization, wounded cultures were generated as above, maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2 for different times, and fixed in ice-cold methanol. Coverslips were incubated with an anti-pericentrin antibody (Covance Research Products) for MTOC staining and counterstained with DAPI to visualize nuclei. In three independent experiments, ∼100 cells at the wound edge were analyzed and the percentage of cells with the MTOC positioned in the quadrant facing the wound relative to the position of the nucleus was calculated (see Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

Time-lapse confocal microscopy

GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells stably expressing GFP-paxillin were plated on FN-coated glass coverslips and imaged using a DM-IRE2 inverted microscope fitted with TCS-SP2 scan head (Leica). After identification of a cell that had started to adhere, confocal images of GFP at the cell–substrate adhesion level were taken with a 63× oil objective every 15 s for 45 min. Videos were generated using ImageJ software.

FRAP and FLIP experiments

GEβ1 or GEβ3 cells stably expressing GFP-paxillin or GFP-vinculin were plated on FN-coated glass coverslips in complete medium for 2–4 h and subsequently imaged through a 63× oil objective using a DM-IRE2 inverted microscope fitted with a TCS-SP2 scan head in bicarbonate-buffered saline (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, 1 mM CaCl2, 23 mM NaHCO3, and 10 mM Hepes, pH 7.2) at 37°C and 5% CO2.

For FRAP analysis, a spot of ∼1.3 μm (full width half-maximum) in a GFP-containing cell–matrix adhesion was bleached using an external 488-nm argon laser line for 0.5 s. Subsequently, fluorescence intensity in that spot was measured every 250 ms for 2 min at low laser power (<5% background bleaching). Recovery of fluorescence was analyzed while correcting for background bleaching and stage drifting by analysis of control (nonbleached) cell–matrix adhesions.

For FLIP analysis, a spot in the cytoplasm was bleached using an internal 488-nm laser at high power for 4 s. Subsequently, fluorescence in 10 selected cell–matrix adhesions and control regions was measured at low laser power. This cycle was repeated every 25 s. Loss of fluorescence from cell–matrix adhesions was analyzed while correcting for background bleaching and stage drifting by analysis of background fluorescence and fluorescence in control (nonbleached) cells (see Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1).

Immunofluorescence and Western blotting

For immunofluorescence, cells were fixed in 4% PFA, permeabilized in 0.2% Triton X-100, blocked with 2% BSA, and incubated with AlexaFluor 568–conjugated Phalloidin (Molecular Probes, Inc.), mAbs against paxillin (Transduction Laboratories), or α-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by FITC- or Texas red–labeled secondary antibodies. Preparations were mounted in MOWIOL 4–88 solution supplemented with DABCO (Calbiochem) and analyzed using a DM-IRE2 inverted microscope fitted with a TCS-SP2 confocal scan head. Images were obtained using a 63× oil objective and were imported in Adobe Photoshop.

For Western blotting, total cell lysates were prepared in SDS sample buffer, resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore), and analyzed by Western blotting using mAbs against GFP (Covance Research Products) or α-tubulin, or with polyclonal antisera against cofilin (provided by Dr. James Bamburg) or pSer3 cofilin (Cell Signaling) followed by HRPO-labeled secondary antibodies (Amersham Biosciences) and ECL using the SuperSignal system (Pierce Chemical Co.).

Biochemical assays for activity of Rho GTPases

The activities of Rac1 and RhoA were determined in GTP pull-down assays as described previously (Danen et al., 2002).

Online supplemental material

Examples of MTOC polarization and FLIP experiments, as well as quantification of the results obtained in transient transfection experiments are provided as supplementary figures. In addition, supplementary videos of migration experiments are provided. Online supplemental material available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200412081/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. James Bamburg, Cord Brakebusch, Reinhard Fässler, Sylvio Gutkind, Wouter Moolenaar, Kenji Moriyama, and Kenneth Yamada for reagents and advice. We also thank Drs. John Collard, Karine Raymond, Ed Roos, Peter Stroeken, and Marc Vooijs for critical reading of the manuscript. Drs. Lauran Oomen and Lenny Brocks are acknowledged for assistance with microscopy.

This work was funded by the Dutch Cancer Society (grant NKI 2003-2858).

Abbreviations used in this paper: FLIP, fluorescence loss in photobleaching; FN, fibronectin; MTOC, microtubule-organizing center.

References

- Agnew, B.J., L.S. Minamide, and J.R. Bamburg. 1995. Reactivation of phosphorylated actin depolymerizing factor and identification of the regulatory site. J. Biol. Chem. 270:17582–17587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers-Loustau, A., J.F. Cote, A. Charest, D. Dowbenko, S. Spencer, L.A. Lasky, and M.L. Tremblay. 1999. Protein tyrosine phosphatase-PEST regulates focal adhesion disassembly, migration, and cytokinesis in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 144:1019–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arber, S., F.A. Barbayannis, H. Hanser, C. Schneider, C.A. Stanyon, O. Bernard, and P. Caroni. 1998. Regulation of actin dynamics through phosphorylation of cofilin by LIM-kinase. Nature. 393:805–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, W.T., N.K. Noren, and K. Burridge. 2002. Regulation of Rho family GTPases by cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion. Biol. Res. 35:239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballestrem, C., B. Hinz, B.A. Imhof, and B. Wehrle-Haller. 2001. Marching at the front and dragging behind: differential αVβ3-integrin turnover regulates focal adhesion behavior. J. Cell Biol. 155:1319–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamburg, J.R. 1999. Proteins of the ADF/cofilin family: essential regulators of actin dynamics. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 15:185–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B., M.P. Williams, and S.D. Blystone. 2003. Ligand-dependent activation of integrin αvβ3. J. Biol. Chem. 278:5264–5270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho, S.Y., and R.L. Klemke. 2002. Purification of pseudopodia from polarized cells reveals redistribution and activation of Rac through assembly of a CAS/Crk scaffold. J. Cell Biol. 156:725–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danen, E.H., P. Sonneveld, A. Sonnenberg, and K.M. Yamada. 2000. Dual stimulation of Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase and RhoA by cell adhesion to fibronectin supports growth factor-stimulated cell cycle progression. J. Cell Biol. 151:1413–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danen, E.H., P. Sonneveld, C. Brakebusch, R. Fassler, and A. Sonnenberg. 2002. The fibronectin-binding integrins α5β1 and αvβ3 differentially modulate RhoA-GTP loading, organization of cell matrix adhesions, and fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 159:1071–1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe, H.R., L.S. Minamide, J.R. Bamburg, and L.P. Cramer. 2003. ADF/cofilin controls cell polarity during fibroblast migration. Curr. Biol. 13:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo, M.A., L.S. Price, N.B. Alderson, X.D. Ren, and M.A. Schwartz. 2000. Adhesion to the extracellular matrix regulates the coupling of the small GTPase Rac to its effector PAK. EMBO J. 19:2008–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DesMarais, V., F. Macaluso, J. Condeelis, and M. Bailly. 2004. Synergistic interaction between the Arp2/3 complex and cofilin drives stimulated lamellipod extension. J. Cell Sci. 117:3499–3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, D.C., L.C. Sanders, G.M. Bokoch, and G.N. Gill. 1999. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:253–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville, S., and A. Hall. 2002. Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature. 420:629–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fincham, V.J., and M.C. Frame. 1998. The catalytic activity of Src is dispensable for translocation to focal adhesions but controls the turnover of these structures during cell motility. EMBO J. 17:81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco, S.J., M.A. Rodgers, B.J. Perrin, J. Han, D.A. Bennin, D.R. Critchley, and A. Huttenlocher. 2004. Calpain-mediated proteolysis of talin regulates adhesion dynamics. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:977–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, B., A. Bershadsky, R. Pankov, and K.M. Yamada. 2001. Transmembrane crosstalk between the extracellular matrix–cytoskeleton crosstalk. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:793–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, M., X. Song, G. Mouneimne, M. Sidani, D.S. Lawrence, and J.S. Condeelis. 2004. Cofilin promotes actin polymerization and defines the direction of cell motility. Science. 304:743–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gimond, C., A. van der Flier, S. van Delft, C. Brakebusch, I. Kuikman, J.G. Collard, R. Fassler, and A. Sonnenberg. 1999. Induction of cell scattering by expression of β1 integrins in β1-deficient epithelial cells requires activation of members of the rho family of GTPases and downregulation of cadherin and catenin function. J. Cell Biol. 147:1325–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlieb, A.I., L.M. May, L. Subrahmanyan, and V.I. Kalnins. 1981. Distribution of microtubule organizing centers in migrating sheets of endothelial cells. J. Cell Biol. 91:589–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic, D., Y. Furuta, S. Kanazawa, N. Takeda, K. Sobue, N. Nakatsuji, S. Nomura, J. Fujimoto, M. Okada, and T. Yamamoto. 1995. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal adhesion contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 377:539–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiosses, W.B., S.J. Shattil, N. Pampori, and M.A. Schwartz. 2001. Rac recruits high-affinity integrin αvβ3 to lamellipodia in endothelial cell migration. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:316–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa, M., T. Ishizaki, S. Boku, N. Watanabe, A. Fujita, A. Iwamatsu, T. Obinata, K. Ohashi, K. Mizuno, and S. Narumiya. 1999. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 285:895–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao, H., S. Li, Y.L. Hu, S. Yuan, Y. Zhao, B.P. Chen, W. Puzon-McLaughlin, T. Tarui, J.Y. Shyy, Y. Takada, et al. 2002. Differential regulation of Rho GTPases by β1 and β3 integrins: the role of an extracellular domain of integrin in intracellular signaling. J. Cell Sci. 115:2199–2206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizejewski, G.J. 1999. Role of integrins in cancer: survey of expression patterns. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 222:124–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriyama, K., K. Iida, and I. Yahara. 1996. Phosphorylation of Ser-3 of cofilin regulates its essential function on actin. Genes Cells. 1:73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouneimne, G., L. Soon, V. DesMarais, M. Sidani, X. Song, S.C. Yip, M. Ghosh, R. Eddy, J.M. Backer, and J. Condeelis. 2004. Phospholipase C and cofilin are required for carcinoma cell directionality in response to EGF stimulation. J. Cell Biol. 166:697–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, R., K. Nagata-Ohashi, M. Takeichi, K. Mizuno, and T. Uemura. 2002. Control of actin reorganization by Slingshot, a family of phosphatases that dephosphorylate ADF/cofilin. Cell. 108:233–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankov, R., and K.M. Yamada. 2002. Fibronectin at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 115:3861–3863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, T.D., and G.G. Borisy. 2003. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 112:453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price, L.S., J. Leng, M.A. Schwartz, and G.M. Bokoch. 1998. Activation of Rac and Cdc42 by integrins mediates cell spreading. Mol. Biol. Cell. 9:1863–1871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, S., A. Vaezi, and E. Fuchs. 2003. A role for αβ1 integrins in focal adhesion function and polarized cytoskeletal dynamics. Dev. Cell. 5:415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.D., W.B. Kiosses, and M.A. Schwartz. 1999. Regulation of the small GTP-binding protein Rho by cell adhesion and the cytoskeleton. EMBO J. 18:578–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, A.J., M.A. Schwartz, K. Burridge, R.A. Firtel, M.H. Ginsberg, G. Borisy, J.T. Parsons, and A.R. Horwitz. 2003. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 302:1704–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottner, K., A. Hall, and J.V. Small. 1999. Interplay between Rac and Rho in the control of substrate contact dynamics. Curr. Biol. 9:640–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahai, E., and C.J. Marshall. 2003. Differing modes of tumour cell invasion have distinct requirements for Rho/ROCK signalling and extracellular proteolysis. Nat. Cell Biol. 5:711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, T., J.M. de la Pena, and D.F. Mosher. 1999. Synergism among lysophosphatidic acid, β1A integrins, and epidermal growth factor or platelet-derived growth factor in mediation of cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15480–15486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schliwa, M., T. Nakamura, K.R. Porter, and U. Euteneuer. 1984. A tumor promoter induces rapid and coordinated reorganization of actin and vinculin in cultured cells. J. Cell Biol. 99:1045–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupack, D.G., and D.A. Cheresh. 2002. ECM remodeling regulates angiogenesis: endothelial integrins look for new ligands. Sci. STKE. 2002:E7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vial, E., E. Sahai, and C.J. Marshall. 2003. ERK-MAPK signaling coordinately regulates activity of Rac1 and RhoA for tumor cell motility. Cancer Cell. 4:67–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt, F.M. 2002. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. EMBO J. 21:3919–3926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb, D.J., K. Donais, L.A. Whitmore, S.M. Thomas, C.E. Turner, J.T. Parsons, and A.F. Horwitz. 2004. FAK-Src signalling through paxillin, ERK and MLCK regulates adhesion disassembly. Nat. Cell Biol. 6:154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, K., I. Mazo, H. Leung, K. Engelke, U.H. von Andrian, E.I. Deryugina, A.Y. Strongin, E.B. Brocker, and P. Friedl. 2003. Compensation mechanism in tumor cell migration: mesenchymal-amoeboid transition after blocking of pericellular proteolysis. J. Cell Biol. 160:267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, N., O. Higuchi, K. Ohashi, K. Nagata, A. Wada, K. Kangawa, E. Nishida, and K. Mizuno. 1998. Cofilin phosphorylation by LIM-kinase 1 and its role in Rac-mediated actin reorganization. Nature. 393:809–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.H., C.K. Qu, O. Henegariu, X. Lu, and G.S. Feng. 1998. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase Shp-2 regulates cell spreading, migration, and focal adhesion. J. Biol. Chem. 273:21125–21131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]