Discrete Cleavage Motifs of Constitutive and Immunoproteasomes Revealed by Quantitative Analysis of Cleavage Products (original) (raw)

Abstract

Proteasomes are the main proteases responsible for cytosolic protein degradation and the production of major histocompatibility complex class I ligands. Incorporation of the interferon γ–inducible subunits low molecular weight protein (LMP)-2, LMP-7, and multicatalytic endopeptidase complex–like (MECL)-1 leads to the formation of immunoproteasomes which have been associated with more efficient class I antigen processing. Although differences in cleavage specificities of constitutive and immunoproteasomes have been observed frequently, cleavage motifs have not been described previously.

We now report that cells expressing immunoproteasomes display a different peptide repertoire changing the overall cytotoxic T cell–specificity as indicated by the observation that LMP-7−/− mice react against cells of LMP-7 wild-type mice. Moreover, using the 436 amino acid protein enolase-1 as an unmodified model substrate in combination with a quantitative approach, we analyzed a large collection of peptides generated by either set of proteasomes. Inspection of the amino acids flanking proteasomal cleavage sites allowed the description of two different cleavage motifs. These motifs finally explain recent findings describing differential processing of epitopes by constitutive and immunoproteasomes and are important to the understanding of peripheral T cell tolerization/activation as well as for effective vaccine development.

Keywords: constitutive proteasomes, immunoproteasomes, CTL epitope, peptide repertoire, tolerance

Introduction

CTLs are crucial for the defense against many invading organisms and certain tumors. Presentation of antigenic peptides bound to MHC class I molecules is a prerequisite for stimulation of a CTL response, and therefore plays a pivotal role in providing CTLs with the capacity to respond to foreign antigens 1.

Peptides that meet the restrictive binding characteristics of MHC class I molecules for presentation to CTLs are generated after intracellular protein degradation by cytosolic proteases. The central enzyme responsible for protein degradation is the proteasome 2. Because of their intimate involvement in antigen processing and presentation 3, detailed knowledge on the cleavage preferences of proteasomes will be crucial for understanding CTL epitope generation and thus, for the regulation of specific immune responses.

The 20S proteasome represents the proteolytic core of the larger 26S proteasome complex that encompasses either one or two regulatory particles of at least 18 subunits 4. The eukaryotic 20S particle is composed of 14 different but related subunits organized in a barrel-shaped complex with the stoichiometry α7β7β7α7. Three subunits of the two inner β-rings (β1, β2, and β5) participate directly in peptide bond cleavage. They represent three distinct proteolytic activities, designated as the chymotrypsin (ChT)-like, trypsin-like, and peptidyl-glutamylpeptide–hydrolyzing (PGPH) activities 5 6. As the NH2-terminal threonine residues responsible for peptide bond cleavage do not prefer certain peptide bonds over others, the basis for the three distinct proteolytic activities most likely resides in the characteristics of the amino acids in the vicinity (pockets) of each active NH2-terminal threonine 7.

Upon IFN-γ exposure of cells, the three active β-subunits that are constitutively expressed in 20S proteasomes can be replaced by three IFN-γ–inducible homologues, low molecular weight protein (LMP)-2 (=β1i) (for Y [β1]), multicatalytic endopeptidase complex–like (MECL)-1 (β2i) (for Z [β2]), and LMP-7 (β5i) (for X [β5]). Although there is extensive sequence homology, these replacements alter the nature of peptides that are generated by proteasomes 8 9 10 11 12.

Proteasomes harboring these IFN-γ–inducible subunits are also called immunoproteasomes, as opposed to the constitutively expressed “constitutive” proteasomes, because immunoproteasomes were found to process a number of viral epitopes with greater efficacy in vitro 13 14 15 16. Using several artificial fluorogenic substrates in vitro, it was found that immunoproteasomes display a better capacity to cleave after hydrophobic and basic residues but are less well equipped for cleavage after acidic amino acids 17. The finding that proteasomes are responsible for the generation of the correct COOH terminus of several CTL epitopes 18 19 and the notion that hydrophobic or positively charged amino acids serve in most cases as COOH-terminal anchor residues of MHC class I ligands led to the concept that immunoproteasomes contribute to more efficient MHC class I antigen processing. While this holds true for most viral antigens, recent studies have shown that some antigenic peptides are efficiently produced by constitutive proteasomes but cannot be generated by immunoproteasomes 20. This demonstrates that immunoproteasomes are not necessarily better suited for the processing of all MHC class I ligands.

To better understand the reasons why certain MHC class I ligands are generated with greater efficiency and others with lower efficiency in cells expressing different sets of proteasomes, we have performed an in-depth analysis of peptide fragments generated after proteasomal cleavage.

We have employed a strictly quantitative method to analyze a large collection of peptide fragments produced by either set of proteasome. Our observations allowed the identification of certain amino acids (or their characteristics) in positions distant, or directly flanking the cleavage sites selected by either set of proteasomes. The (quantified) mapping of cleavage sites using a large protein substrate provides the basis for a better understanding of proteasomal cleavage specificity, allowing a refined proteasomal cleavage prediction, which will be helpful for the identification of new CTL epitopes, the design of new (recombinant) vaccines, and for better insight into immunity against infection.

Materials and Methods

Purification of 20S Proteasomes.

20S proteasomes were isolated as described previously 9. Frozen pellets of LCL-721 cells or LCL-721.174 cells were lysed in a buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 on ice and homogenized in a Dounce homogenizer. The 40,000× g supernatant of the lysate was bound to DEAE Sephacel. After elution, the protein fraction was concentrated and loaded onto a 10–40% sucrose gradient. After centrifugation, gradient fractions were tested for protease activity using the fluorogenic substrates succinyl-leucyl-leucyl-valyl-tyrosyl-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC) and succinyl-tyrosyl-valyl-alanyl-aspartyl-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-YVAD-AMC). Active fractions were pooled and further purified by anion exchange chromatography on a MonoQ HR5/5 FPLC column (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The purity of the proteasome preparates, checked by SDS-PAGE, was >95%. Quantification of native proteasome protein was determined by a variation of the Lowry Method (protein assay; Bio-Rad Laboratories) and BSA as a standard.

Immunoblotting.

5 μg of purified proteasome polypeptides were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinyldifluoride (DuPont) with a semidry transfer system. Human LMP-7 was detected using a rabbit polyclonal antiserum in conjunction with chemiluminescence (PW8200; Affiniti Research Products, Ltd.).

In Vitro Degradation of Enolase-1.

150 μg of yeast enolase-1 were incubated in digestion buffer (20 mM Hepes/KOH, pH 7.6, 2 mM MgAc2, and 0.01% SDS) with proteasomes at a molar ratio of 150:1. Digestions were stopped by freezing the samples at −80°C when ∼50% of the substrate was digested (usually after ∼48 h).

Separation and Analysis of Cleavage Products.

For the separation of degradation products, unfractionated enolase digests were subjected to μRP SC 2.1/10 columns (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) on a Microbore HPLC system (SMART; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Buffer A contained 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid; buffer B contained 0.081% trifluoroacetic acid and 80% acetonitrile. Gradients were 0% for 5 min, in 40 min to 40% in buffer B, in 8 min to 75% in buffer B, and up to 85% in another 7 min at a flow rate of 150 μl/min. Fractions were collected by peak fractionation with a maximal volume of 500 μl/peak.

Peak fractions were dried and dissolved in 25 μl of 40% methanol, 1% formic acid, and subsequently analyzed by matrix-associated laser desorption ionization (MALDI) time of flight mass spectrometry (MS) (G2025A; Hewlett Packard) and NH2-terminal sequencing (Edman degradation) (pulsed liquid protein sequencer procise 494A; Applied Biosystems). Alternatively, peptides were analyzed on a hybrid quadruple orthogonal acceleration tandem mass spectrometer (Micromass). All these techniques were applied as described previously 21. Pmol amounts for each peptide detected in the HPLC fraction were determined by Edman sequencing and used for the quantitative analysis of the data.

Statistical Analysis - Frequencies of Amino Acids.

To detect statistically significant features in the amino acid distribution flanking the cleavage sites, we compared percent values using a classic chi-squared test for four tables (variance assumed due to counting). This method was used to compare constitutive and immunoproteasomes fragments with each other and with enolase. For a more thorough comparison of the absolute pmol amounts of constitutive and immunoproteasomes, we accounted for the experimental variability and, according to the quasilikelihood approach of Wedderburn et al. 22, assumed a mean variance structure. We assumed the variance to be proportional to the mean and fitted the proportionality constant α from all the data. Then, the usual chi-squared test variable was scaled by 1/α, which led asymptotically to a test variable that is chi-squared distributed with one degree of freedom. The results of the latter was a more thorough approach correlated to the approach neglecting experimental variability and using percent values. Only chi-squared values >3.841 are considered to be significant.

Statistical Analysis - Comparison of Amino Acid Characteristics.

To compare the characteristics of amino acids, the observed frequencies of amino acids at P6 to P6′ around cleavage sites in both proteasomes were compared with each other using the chi-squared test. Hydrophobicity, bulkiness, and flexibility characteristics 21 of both proteasomes and enolase were compared by translating the percentage of amino acids found to the corresponding hydrophobicity, bulkiness, and flexibility scales. This resulted in spectra per cleavage site, and these were compared by means of regression analysis.

Mice, CTL Assays, and Skin Grafting.

LMP-7−/− mice were generated as described previously 23 and maintained at the animal facilities of the Basel Institute for Immunology or the Institute for Cell Biology. C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Charles River Laboratories. RMA and RMA-S cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 2-Me, l-glutamine, and antibiotics. CTLs were generated by intraperitoneal immunization of mice with 107 irradiated spleen cells (33Gy) in 300 μl PBS. 10 d later spleens were removed and the splenocytes were stimulated with irradiated spleen cells (33Gy). CTL lines were generated by weekly restimulations with irradiated spleen cells as described previously 24. CTL assays were performed as described previously 24 using RMA, RMA-S, and concanavalin A blasts of spleen cells as target cells. In addition, CTL lines were tested on the LMP-7−/− cell line BII-103 (unpublished data) and BII-103 transfected with LMP-7 wild-type and LMP-7 T1A DNA.

The LMP-7 gene was cloned from a 129/Ola cDNA using oligonucleotides 5′ AGGATCCACCATGGCGTTACTGGATCTGTGCGG (with BamH1 site at the 5′ end) and 3′ TGAATTCTCACAGAGCGGCCTCTC (with EcoR1 site at the 3′ end). The DNA fragment was then digested with EcoR1 and BamH1 endonucleases and cloned into similarly digested LZRSpBMN-linker-IRES-green fluorescent protein plasmid (unpublished data). Mutagenesis of LMP-7 to replace T by A at position 1 (in the processed subunit) was done using oligonucleotides 5′ GGCCCACGGCGCAACCACACTCGCC and 3′ GGCGAGTGTGGTTGCGCCGTGGGCC. LMP-7 wild-type and LMP-7 T1A expressing retroviral vectors were transfected into packaging cell lines and supernatants were used to infect the LMP-7−/− cell line BII-103. After appropriate selection, comparable LMP-7 wild-type and LMP-7 T1A transcription was detected by Northern blot analysis and comparable green fluorescent protein expression by FACS® analysis (FACSCalibur™; Becton Dickinson).

Skin grafts were performed on the back of the mice. Pieces of skin (∼7 mm of diameter) were obtained with a punch from the back of shaved donors and grafted onto anesthesized recipients where holes had also been made with a punch. Each animal had two separated grafts, foreign and autologous, as an experimental control. The skin was discreetly glued (histoacryl; B. Braun Surgical AG) and bandaged. After a week, the bandage was removed to allow the observation of the putative graft rejection.

Results

Isolation of Proteasomes.

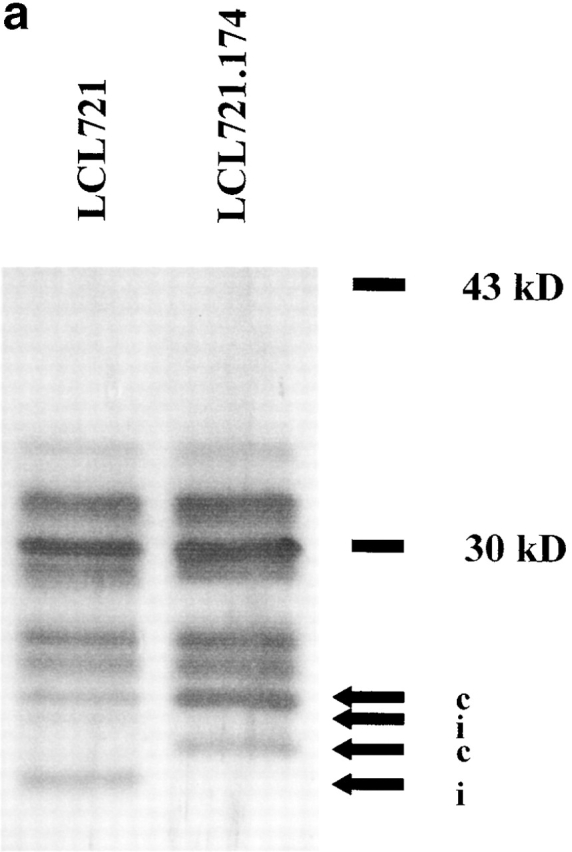

Proteasomes were isolated from EBV-transformed B cells. Constitutive proteasomes were purified from cells (LCL-721.174) lacking LMP-2 and LMP-7 due to a chromosomal deletion in the MHC locus 20 25. The lack of LMP-2 excludes the incorporation of MECL-1 in 20S proteasomes. Therefore, this cell line contains only proteasomes carrying active constitutive subunits 26. The immunoproteasome preparation was isolated from the parental line (LCL-721) that served for the generation of LCL-721.174.

As expected, only proteasomes isolated from LCL-721 cells expressed immuno subunits, as exemplified by the presence of LMP-7 (Fig. 1, a and b). Moreover, these proteasomes showed a reduced ability to release fluorogenic groups linked to acidic amino acids compared with proteasomes isolated from LCL-721.174 cells (data not shown). Together, these data indicate that proteasomes purified from LCL-721, although containing some constitutive proteasomes, behave like immunoproteasomes with very little PGPH activity, whereas LCL-721.174–derived proteasomes can be classified as constitutive proteasomes with high PGPH activity.

Figure 1.

Immunosubunit incorporation into 20S proteasomes purified from LCL-721 cells (left) but not into 20S proteasomes derived from LCL-721.174 cells (right). 20S proteasomes were isolated from LCL-721 and LCL-721.174 cells as described in Materials and Methods. Proteasome subunits were separated by SDS-PAGE (a) and probed with an LMP-7–specific antiserum (b). LMP-7 was only detected in 721 proteasomes. i or c indicate subunits exclusively present or overexpressed in i20S or c20S proteasomes, respectively.

Digestion of Enolase.

Although the ability of constitutive and immunoproteasomes to cleave a set of standard fluorogenic substrates or some CTL epitope containing peptides has been well documented, little is known about the selection of cleavage sites during the degradation of proteins, especially on a quantitative basis. To obtain further insight into these cleavage preferences, we used the complete protein enolase-1 from yeast as substrate which can be digested by proteasomes in vitro without prior modifications. Enolase is a 436 amino acid–long protein in which the frequency of amino acids resembles the average amino acid frequency in proteins 27. Digestion of enolase was performed by incubation of enolase with constitutive or immunoproteasomes at a molar ratio of 150:1. The reaction was stopped when ∼50% of the substrate was degraded to ensure comparable substrate turnover. This degree of degradation was obtained after 48 h, indicating similar rates of digestion for both constitutive and immunoproteasomes. Subsequently, enolase fragments were separated by reverse-phase HPLC. Comparison of two independent digests obtained after incubation with two independent constitutive proteasome batches revealed that highly comparable degradation profiles were obtained. The generation of similar degradation products was confirmed by MALDI-MS analyses of several fractions that eluted at the same time (data not shown).

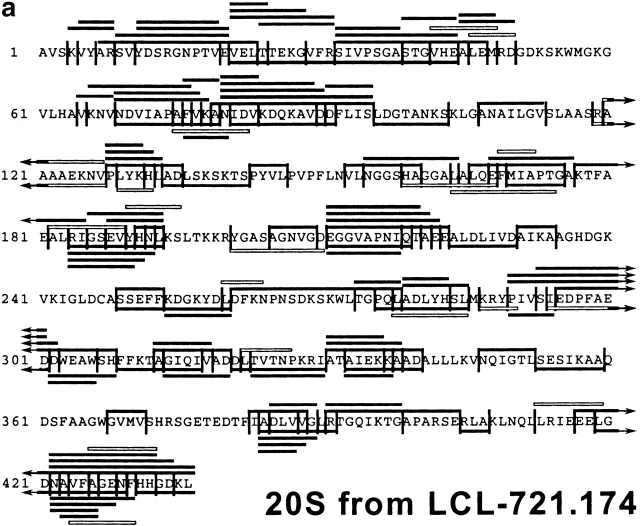

After having established the reproducibility of the digestion profiles, the peptide fragments in all fractions were analyzed by MALDI-MS, in combination with Edman degradation, and compiled in a digestion map (Fig. 2). Approximately 50% of cleavages generated by constitutive proteasomes were not produced by immunoproteasomes. Indeed, when the identity of fragments produced by either set of proteasome was compared on a qualitative basis only ∼25% of peptides produced by immunoproteasomes were also found in constitutive proteasome digests. Therefore, the pool of peptides generated by cells expressing immunoproteasomes is very different from the peptide pool generated by cells harboring constitutive proteasomes only.

Figure 2.

Digestion map generated from degradation of enolase by constitutive proteasomes (a) and immunoproteasomes (b). Vertical lines, cleavage sites determined by Edman degradation and/or MS; black bars, degradation products identified by Edman degradation in combination with MS; white bars, degradation products identified by Edman degradation only (COOH terminus of peptide not identified).

Quantification of Digestion Profiles.

For careful examination of proteasomal cleavage preferences, it is important to know the quantity of each fragment to calculate how often particular cleavage sites are selected. In contrast to MS data, data acquired by Edman sequencing are quantitative and can thus be used to determine the amount of peptide liberated. The combination of MS analysis and the quantified Edman sequencing data identified the absolute amount of each peptide detected in HPLC fractions. In the constitutive proteasome digests, a total of 136 fragments was detected, representing 6,135 pmol of peptide (Table ). By adding the pmol of all fragments starting or ending at a particular cleavage site (and then choosing the higher one of the two sums), pmol amounts of peptide generated from a given cleavage site, and thus the frequency of cleavage site utilization, was determined. The most frequently used cleavage sites were found at amino acid positions 278 and 404, resulting in the liberation of 265 pmol peptide each (Table , top). As usage of many other cleavage sites resulted in only 5 pmol of peptide, these data indicate that the relative usage of cleavage sites within one protein can differ substantially.

Table 1.

Absolute Amounts of Amino Acids Found in Positions P6 to P1 and P1′ to P6′ of Peptides Generated by Constitutive Proteasomes

| Pos | Pmol | P6-P1 | P1′-P6′ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 278 | 265 | LTGPQL | ADLYHS | |||||||||

| 404 | 265 | APARSE | RLAKLN | |||||||||

| 383 | 185 | TEDTFI | ADLVVG | |||||||||

| 31 | 175 | EKGVFR | SIVPSG | |||||||||

| 142 | 165 | SKSKTS | PYVLPV | |||||||||

| 183 | 165 | TFAEAL | RIGSEV | |||||||||

| 230 | 165 | LDLIVD | AIKAAG | |||||||||

| 330 | 155 | TNPKRI | ATAIEK | |||||||||

| 146 | 150 | TSPYVL | PVPFLN | |||||||||

| 79 | 145 | PAFVKA | NIDVKD | |||||||||

| P6 | P5 | P4 | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | P2′ | P3′ | P4′ | P5′ | P6′ | |

| A | 865 | 595 | 1,020 | 485 | 620 | 825 | 1,545 | 330 | 710 | 590 | 930 | 365 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 130 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 580 | 460 | 255 | 215 | 185 | 805 | 300 | 1,185 | 315 | 235 | 170 | 400 |

| E | 530 | 465 | 385 | 455 | 250 | 605 | 300 | 275 | 460 | 150 | 465 | 440 |

| F | 50 | 275 | 430 | 165 | 430 | 145 | 190 | 250 | 165 | 575 | 220 | 50 |

| G | 300 | 575 | 750 | 230 | 545 | 175 | 185 | 415 | 760 | 185 | 320 | 780 |

| H | 175 | 125 | 10 | 150 | 280 | 65 | 165 | 110 | 65 | 35 | 385 | 90 |

| I | 505 | 125 | 385 | 335 | 180 | 510 | 60 | 845 | 220 | 450 | 405 | 170 |

| K | 220 | 580 | 240 | 945 | 455 | 80 | 365 | 115 | 370 | 675 | 600 | 655 |

| L | 540 | 550 | 535 | 525 | 230 | 1,185 | 345 | 900 | 1,120 | 435 | 670 | 565 |

| M | 10 | 0 | 95 | 10 | 15 | 35 | 70 | 40 | 75 | 65 | 10 | 60 |

| N | 120 | 285 | 235 | 140 | 240 | 95 | 390 | 215 | 195 | 160 | 270 | 730 |

| P | 365 | 475 | 550 | 365 | 95 | 40 | 480 | 20 | 255 | 240 | 330 | 315 |

| Q | 45 | 260 | 25 | 20 | 340 | 60 | 75 | 60 | 155 | 305 | 35 | 75 |

| R | 125 | 45 | 45 | 425 | 290 | 275 | 595 | 95 | 155 | 145 | 80 | 60 |

| S | 575 | 365 | 380 | 90 | 535 | 395 | 500 | 215 | 170 | 530 | 490 | 555 |

| T | 735 | 460 | 140 | 365 | 365 | 140 | 150 | 430 | 140 | 360 | 250 | 105 |

| V | 270 | 380 | 365 | 920 | 840 | 450 | 275 | 410 | 695 | 705 | 355 | 695 |

| W | 40 | 15 | 35 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 10 |

| Y | 85 | 100 | 255 | 265 | 90 | 220 | 145 | 175 | 110 | 295 | 100 | 15 |

| sum (pmol) | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 | 6,135 |

Similar data were obtained when the immunoproteasome digest was analyzed (123 peptides representing 6,370 pmol of peptide; Table ). The most prominent cleavage site was found at amino acid position 419, resulting in the generation of 250 pmol peptide (Table , top). As for constitutive proteasomes, many other cleavage sites were used less often, indicating that both proteasome species prefer certain peptide bonds over others as cleavage sites. The almost identical amounts of peptides generated by both proteasomes (6,135 pmol versus 6,370 pmol) demonstrate a comparable substrate turnover, allowing a direct comparison of pmol amounts of amino acids at different positions around cleavage sites as well as a comparative statistical analysis of both digests.

Table 2.

Absolute Amounts of Amino Acids Found in Positions P6 to P1 and P1′ to P6′ of Peptides Generated by Immunoproteasomes

| Pos | Pmol | P6-P1 | P1′-P6′ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 419 | 250 | RIEEEL | GDNAVF | |||||||||

| 390 | 200 | DLVVGL | RTGQIK | |||||||||

| 183 | 155 | TFAEAL | RIGSEV | |||||||||

| 313 | 155 | HFFKTA | GIQIVA | |||||||||

| 133 | 150 | PLYKHL | ADLSKS | |||||||||

| 142 | 150 | SKSKTS | PYVLPV | |||||||||

| 253 | 150 | ASSEFF | KDGKYD | |||||||||

| 285 | 150 | DLYHSL | MKRYPI | |||||||||

| 289 | 150 | SLMKRY | PIVSIE | |||||||||

| 383 | 150 | TEDTFI | ADLVVG | |||||||||

| P6 | P5 | P4 | P3 | P2 | P1 | P1′ | P2′ | P3′ | P4′ | P5′ | P6′ | |

| A | 680 | 615 | 940 | 420 | 590 | 745 | 1,440 | 665 | 560 | 775 | 480 | 810 |

| C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | 725 | 360 | 190 | 225 | 160 | 150 | 335 | 1,210 | 255 | 325 | 220 | 375 |

| E | 300 | 370 | 515 | 870 | 580 | 155 | 255 | 320 | 410 | 270 | 400 | 515 |

| F | 0 | 495 | 280 | 105 | 665 | 550 | 50 | 100 | 120 | 260 | 190 | 250 |

| G | 500 | 550 | 485 | 180 | 360 | 170 | 880 | 475 | 970 | 265 | 465 | 675 |

| H | 300 | 35 | 80 | 285 | 205 | 130 | 140 | 40 | 50 | 40 | 340 | 285 |

| I | 440 | 345 | 290 | 470 | 145 | 585 | 20 | 800 | 295 | 420 | 730 | 395 |

| K | 90 | 475 | 400 | 1,065 | 620 | 175 | 450 | 275 | 290 | 405 | 590 | 830 |

| L | 560 | 975 | 450 | 235 | 160 | 2,305 | 65 | 370 | 1,025 | 410 | 105 | 510 |

| M | 20 | 0 | 215 | 10 | 80 | 50 | 295 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 50 |

| N | 245 | 285 | 290 | 165 | 205 | 95 | 520 | 290 | 560 | 575 | 190 | 290 |

| P | 325 | 370 | 255 | 380 | 35 | 0 | 375 | 175 | 305 | 180 | 440 | 80 |

| Q | 10 | 260 | 210 | 105 | 170 | 10 | 175 | 75 | 225 | 250 | 100 | 20 |

| R | 365 | 100 | 65 | 215 | 395 | 200 | 480 | 0 | 190 | 290 | 320 | 100 |

| S | 545 | 250 | 610 | 225 | 735 | 185 | 345 | 320 | 265 | 695 | 380 | 520 |

| T | 890 | 200 | 85 | 235 | 570 | 195 | 310 | 560 | 275 | 195 | 275 | 55 |

| V | 255 | 485 | 585 | 940 | 695 | 320 | 85 | 535 | 495 | 555 | 925 | 610 |

| W | 25 | 60 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 0 |

| Y | 95 | 140 | 425 | 215 | 0 | 280 | 150 | 160 | 80 | 285 | 220 | 0 |

| sum (pmol) | 6370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 | 6,370 |

Comparison on a qualitative and quantitative basis of the fragment length distributions revealed that both proteasome species generated peptides with an average length of 7–9 amino acids (c20S, 7.4 aa; i20S, 8.6 aa) with 30% of the peptides produced by constitutive proteasomes being identical to those generated by immunoproteasomes (Fig. 2). Together, these findings strongly indicate that in cells harboring constitutive or immunoproteasomes, respectively, the pool of peptides generated from proteasomal protein turnover will differ substantially.

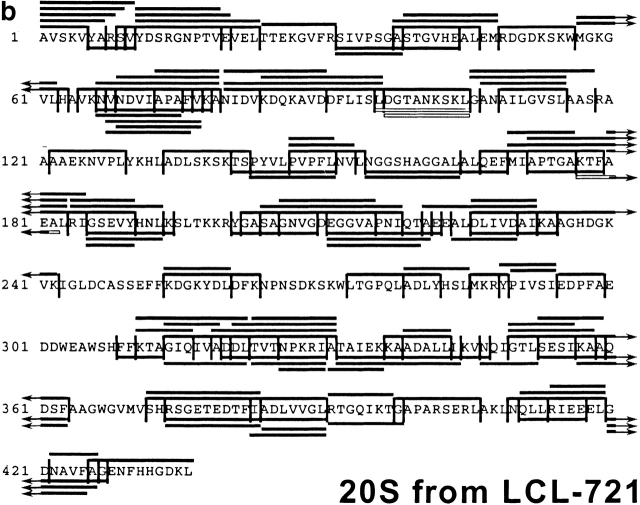

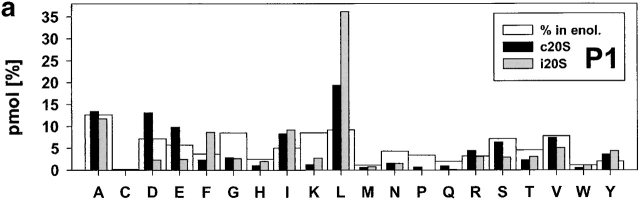

Analysis of Cleavage Site Usage.

As outlined above, some cleavage sites are used often, whereas others are used less frequently or not at all by one or both proteasome species. Until now, most studies addressing the specificity of proteasomal peptide/protein degradation did not take the frequency of cleavages into account. To study more accurately the influence of all 20 amino acids flanking proteasomal cleavage sites, we determined the frequency of amino acids around cleavage sites (P6 to P1 NH2-terminal of cleavage site; P1′ to P6′ COOH-terminal of cleavage site) using the quantified data set described above (Table and Table , and Fig. 3). No statistically significant differences in cleavage site selection were observed between two independent digests performed by two independent immunoproteasome batches, indicating that the fragment pattern obtained after proteasomal degradation was highly reproducible (data not shown).

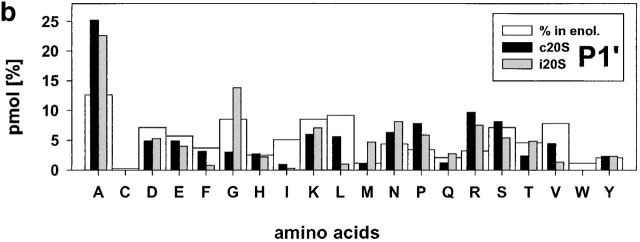

Figure 3.

Relative frequencies of amino acids in position P1 (a) P1′ (b). The absolute amount of amino acids found in a defined positions (P6 to P6′) around cleavage sites used by constitutive proteasomes and immuoproteasomes was divided by the total amount of peptides detected in the digests resulting in the relative frequency of amino acid usage in that position. Big white bars, relative frequency of amino acids found in enolase; black bars, relative frequency of amino acids at P1 or P1′ positions in peptide fragments generated by constitutive proteasomes; grey bars, relative frequency of amino acids at P1 or P1′ in peptide fragments generated by immunoproteasomes.

Examination of cleavages performed by immunoproteasomes revealed several deviations from randomness at the amino acid level (i.e., the background in enolase) as determined by chi-squared analyses (data not shown). L as P1 residue has the highest preference (chi-squared = 21) and reflects a pronounced ChT-like activity within immunoproteasomes. Weaker preferences for D at P2′ (chi-squared = 6.2) are also evident. On the other side, several residues are found less frequently than expected with the hydrophobic amino acids I, L, and V (chi-squared = >4.3) at P1′ being the most prominent. This finding reflects the preference of proteasomes to cleave behind rather than in front of L residues, for example. Apart from these amino acids at the P1′ position, L at P2 was found less abundantly than expected. When amino acids are grouped according to their characteristics, it was found that there was a positive correlation between cleavage and the presence of hydrophobic, and bulky amino acids in P1 (P < 0.0002).

An analogous examination for the cleavages selected by constitutive proteasomes revealed that the frequency of S as P3 and the positively charged amino acid K as P1 and P2′ residue is reduced (all chi-squared = 3.9), indicating that these amino acids are disfavored by constitutive proteasomes at these positions. Constitutive proteasomes show a weak enrichment of P at P4 (chi-squared = 3.8) and, like immunoproteasomes, prefer A at P1′ and L as P1 residue (albeit to a lesser extent; chi-squared = 4.2). Similarly, an enrichment for D at P2′ was noted (chi-squared = 8.5), indicating that both proteasome species have a preference for negatively charged amino acids at the P2′ position. When comparing characteristics of amino acids at these positions, a preference for hydrophobic, bulky amino acids in P1 and P2′ (P < 0.0002) was observed. There is a negative correlation between cleavage site selection and the presence of hydrophobic, bulky amino acids in P1′ (P < 0.0002).

Effect of Immunosubunit Incorporation on Cleavage Site Selection.

The data described above reveal that both proteasome species exhibit a different, but partially overlapping (L in P1, A in P1′, and D in P2′) cleavage preference. However, they do not address directly the influence of immunosubunit incorporation on cleavage site selection. Therefore, we compared relative amino acid frequencies around cleavage sites used by immunoproteasomes to those used by constitutive proteasomes. As a control, we evaluated cleavage site selection of two independent immunoproteasome batches yielding no statistically significant differences (data not shown). For comparison between constitutive and immunoproteasomes for positions P6-P6′, significant differences were found at position P1 (P < 0.004) and, to a lesser extent, also at P1′. When testing for amino acid characteristics, we found that immunoproteasomes prefer bulky, hydrophobic amino acids at P1 (P < 0.003) but dislike flexible amino acids at this position (P < 0.001). At position P1′ we found that hydrophobic, bulky amino acids were favored more by constitutive proteasomes (P < 0.04). Thus, comparison of peptide bonds used as cleavage sites by immunoproteasomes to the ones used by constitutive proteasomes revealed a pronounced ChT-like activity of immunoproteasomes, as is reflected by a strong enrichment of hydrophobic amino acids in P1. When comparing the two proteasome species for individual amino acid usage, a strong enrichment of L (chi-squared = 7.1 and, to a lesser extent F, chi-squared = 3.8) was detected at P1 in peptides generated by immunoproteasomes. The strong enrichment of L became most prominent when we analyzed in detail those cleavages exclusively generated by immunoproteasomes, as 43% of these cleavages were performed after L (data not shown). Acidic amino acids D and E in P1 exert a negative influence on cleavage site selection by immunoproteasomes (chi-squared = 4.5 and 8.1, respectively). G in P1′ is enriched in peptides generated by immunoproteasomes (chi-squared = 7.8), pointing to a preference of immunoproteasomes for this small amino acid in P1′. Analysis of amino acid frequencies at positions P2 to P6 and P2′ to P6′ showed that L at P2′ is disfavored by immunoproteasomes (chi-squared = 4.3).

Effect of Immunosubunit Incorporation on CTL Induction.

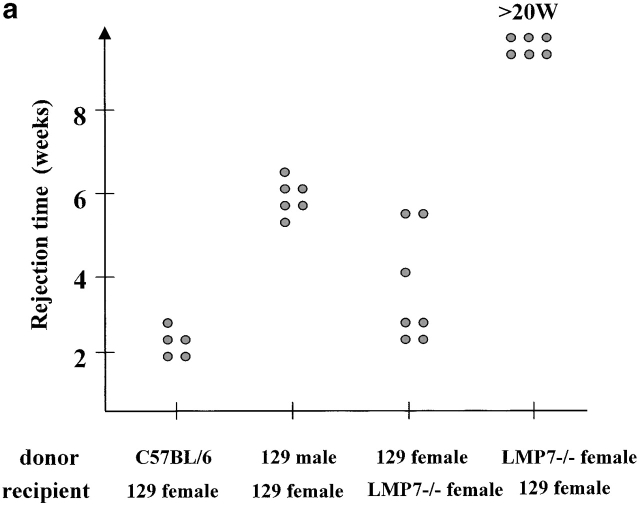

The observed major differences in the peptide repertoire produced by constitutive and immunoproteasomes could have important biological implications that go beyond differential proteasomal processing of certain CTL epitopes 8 13 14 15 16 20. To study the biological consequences of immunosubunit incorporation in vivo, we tested the immune response of LMP-7−/− mice lacking functional immunoproteasomes 28 against wild-type cells. If immunoproteasome incorporation affects the nature of the CTL epitopes presented, it is expected that wild-type cells expressing both constitutive and immunoproteasomes will induce a CTL response in mice expressing constitutive proteasomes only. The opposite direction should not lead to a CTL response, as no unique (“immuno”) peptides are presented in this setting. Indeed, skin grafting experiments showed that wild-type mice were not able to reject skin from LMP-7−/− animals 23, which are not able to express functional immunoproteasomes because in the absence of the LMP-7 subunit, LMP-2 and MECL-1 subunits are only incorporated in 20S proteasomes as inactive precursors 28. However, LMP-7−/− mice rejected skin transplants from wild-type mice with even greater efficiency than observed for the rejection of male skin by female recipients (Fig. 4 a). The fact that the latter rejection is mediated over several antigenic differences 29 supports the argument that LMP-7−/− mice react against multiple antigenic differences present on LMP-7 wild-type skin.

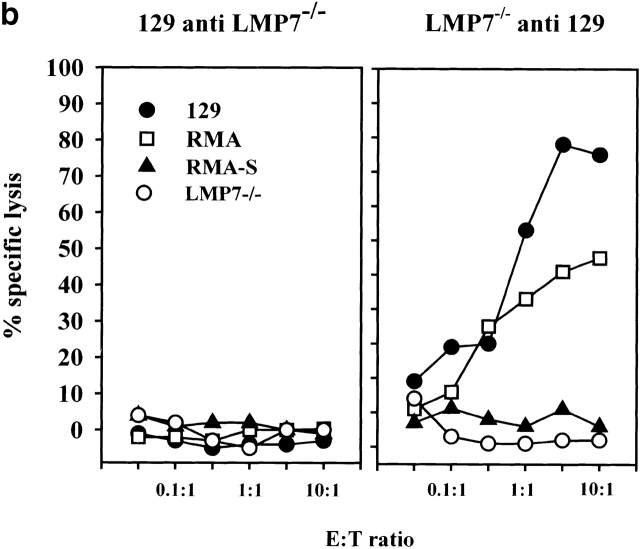

Figure 4.

(a) Skin of the indicated donors were grafted on the back of the indicated recipient mice according to the protocol described in Materials and Methods. Graft rejection was controlled daily. Each dot represents a single recipient. This graph shows a representative result of four independent experiments. (b) LMP-7−/− mice and wild-type littermates (129/Ola background) were immunized with wild-type or LMP-7−/− splenocytes. CTL activity was tested after in vitro stimulation on LMP-7−/− and wild-type concanavalin A blasts, RMA, and RMA-S cells as described in Materials and Methods. This graph shows a representative result of three independent experiments.

The identical scenario was observed for the induction of CTL responses. Vaccination of wild-type mice with cells derived from LMP-7−/− mice did not generate a CTL response. In contrast, LMP-7−/− mice readily mounted a strong, transporter-associated with antigen processing (TAP)-dependent CTL response upon vaccination with wild-type cells harboring both proteasome species (Fig. 4 b). Cell lines expressing an inactive LMP-7 T1A subunit were recognized with a 30-fold lower efficiency compared to cells expressing the LMP-7 wild-type subunit despite equal expression levels of both gene products and H-2 class I molecules (data not shown). This finding argues against the possibility that CTL responses against a peptide from the LMP-7 protein itself have been induced. The fact that LMP-7 T1A transfectants are still recognized to some extent by CTLs from LMP-7−/− mice can be explained by the observation that some CTL epitopes, not produced in LMP-7−/− mice, can be generated by proteasomes carrying both catalytically active or inactive LMP-7 subunits, as reported for immunoproteasome-mediated CTL epitope generation from viral antigens 14 30. The recognition of these epitopes on LMP-7 T1A transfectants would result in a CTL activity above the one induced by LMP-7−/− cells but below the one induced by LMP-7 wild-type cells.

Together, our findings indicate that the incorporation of immunosubunits strongly influences the repertoire of peptides presented to CTLs and thereby the overall specificity of the CTL response.

Discussion

The proteasome is the key enzyme responsible for cytosolic protein degradation and generation of peptides that are presented by MHC class I molecules by liberation of their proper COOH termini. However, proteasomes also can prevent MHC class I presentation by destruction of potential MHC ligands or their inability to select the proper COOH-terminal cleavage site. Cleavage site selection might change substantially after incorporation of IFN-γ–inducible subunits, as indicated by experiments using small fluorogenic substrates or short synthetic peptides. Therefore, detailed knowledge on the specificity of protein degradation by either constitutive or immunoproteasomes is crucial to the understanding and prediction of CTL epitope generation.

To analyze alterations of cleavage preference upon immunosubunit incorporation we used an entire protein as a substrate without modification of amino acids or bias to known CTL epitopes. The quantitative identification of >120 peptide fragments generated by either constitutive or immunoproteasomes allowed a detailed analysis of the cleavage specificities. Our data reveal that especially the amino acids in P3 to P3′ have a strong influence on cleavage site selection as the observed frequencies of amino acids in these locations showed the largest discrepancy to their background frequencies in enolase. Nonetheless, amino acids further away most likely influence cleavage site selection as well, as was reported earlier for the effect of P at P4 on peptide bond cleavage by yeast and constitutive human proteasomes 21 31 32 33. The average length of fragments produced by either set of proteasome is the same, showing that spacing at which specific cleavage sites of the substrate are recognized is not changed by immunosubunit incorporation.

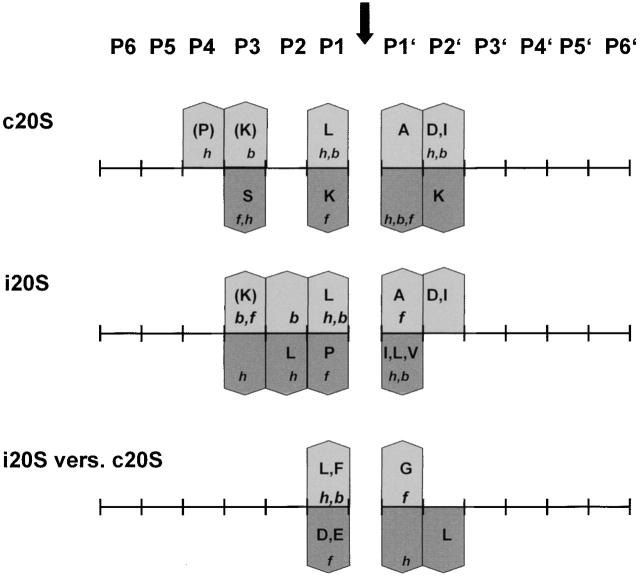

By comparing flanking residues around cleavage sites, we found that both proteasomes display a partially overlapping but different cleavage specificity (Fig. 3 and Fig. 5). They both prefer L as P1 residue and K in P3; A in P1′ and D in P2′ were also favored. Nonetheless, immunoproteasomes have a much stronger preference for L at P1, as well as other hydrophobic amino acids in this position. These findings point to a pronounced ChT-like activity after immunosubunit incorporation. In contrast, the acidic amino acids D and E were clearly disfavored by immunoproteasomes, whereas these amino acids were enriched at P1 in peptides generated by constitutive proteasomes. Some of the different characteristics regarding amino acid preferences at the P1 position were also observed previously in a small number of fragments generated from covalently modified lysozyme using proteasomes from bovine spleen and pituitaries 12.

Figure 5.

Summary of cleavage motifs. Amino acid preferences at positions flanking the cleavages performed by constitutive (c20S) or immunoproteasomes (i20S) are indicated by bars pointing up (enriched) or down (decreased). Amino acid frequencies around cleavage sites were compared with amino acid frequencies in enolase. i20S versus c20S indicates a comparison of amino acid preferences between both types of proteasomes. Amino acid frequencies around cleavage sites were compared with each other. Bars pointing up indicate a i20S preference, bars pointing down indicate a c20S preference. Amino acids are shown in one-letter code by capital letters, and amino acid characteristics are indicated by small letters. A decrease in preferences for hydrophobic and bulky amino acids also indicates an increase in preferences for polar and small amino acids, respectively and vice versa. h, hydrophobic; f, flexible; b, bulky.

Our observations most likely reflect the characteristics of amino acids at the inner surface of the proteasome. Analysis of the contribution of individual active β subunits to cleavage site selection in yeast 20S proteasomes 5 21, revealed that the active site of β1 prefers to cleave after acidic residues, β2 after basic residues, and β5 after hydrophobic residues. Structural analysis of proteasomes has shown that the pockets around the active site threonine of β5 and β2 do not change after immunosubunit incorporation 7. Therefore, it can be expected that the cleavage site–flanking amino acids that are preferred by both proteasomes (K in P3, L in P1, A in P1′, and D in P2′) correlate with the characteristics of amino acids in the vicinity of the S-1 pockets of β5/ β5i and/or β2/β2i.

The enhanced preference for hydrophobic amino acids at P1 of immunoproteasomes does not probably result from exchange of β5, which mediates the ChT-like activity, for β5i (LMP-7), as replacement of β5 for β5i does not alter the pocket surrounding the active site threonine. Moreover, functional data indicate that β5i influences the structural features of 20S proteasomes, thereby enhancing the activity of β1i (LMP-2; references 14 and 30). The stronger preference of immunoproteasomes for hydrophobic amino acids at P1, however, correlates with the characteristics at the inner surface of the proteasome when β1 (Y) is replaced for β1i. Replacement of β1 for β1i is predicted to cause the formation of a more apolar pocket around the active site threonine. This most likely results in the accommodation of hydrophobic amino acids at P1, leading to an enrichment of peptides with hydrophobic COOH termini and a reduction of fragments with charged COOH termini 7. Thus, it is conceivable that the exchange of β1 for β1i causes a reduction of peptides with charged COOH termini (amino acids like D and E) and enhanced liberation of peptides with hydrophobic COOH termini.

Structural analyses of proteasomes also predict that the active S-1 pocket of β5i is more constricted than the pocket of β5 7. As most hydrophobic amino acids are rather bulky, it is possible that small and flexible amino acids, like G, in close vicinity to hydrophobic amino acids, support accommodation of these amino acids in the S1 pocket of β5i most efficiently. Therefore, we anticipate that the strong enrichment of G and the decrease of hydrophobic amino acids in P1′ of cleavage sites selected by immunoproteasomes are a direct consequence of these altered characteristics of the β5 immunosubunit.

The observation that the P1 preference of immunoproteasomes closely resembles the preferences of the F pocket of most MHC class I molecules is thought to explain why immunoproteasomes are associated with more efficient processing of MHC class I ligands, either by generating CTL epitopes directly or by producing more CTL epitope precursors that are converted into CTL epitopes by the action of aminopeptidases. As some CTL epitopes are preferentially generated by immunoproteasomes 34, it is postulated that immunoproteasome expression is generally associated with more efficient CTL epitope generation. However, the correlation between epitope production and expression of immunoproteasomes is more subtle. Some MHC class I alleles harbor F pockets that allow the binding of amino acids with charged polar side chains (e.g., K and R). These MHC alleles are unlikely to profit from immunoproteasome expression, as the trypsin-like activity is not enhanced by immunosubunit incorporation.

In view of our results, increased CTL epitope generation can now be explained and also predicted by several different mechanisms. Examples of quantified fragment generation from synthetic peptides by constitutive and immunoproteasomes are listed in Table . They include (a) enhanced liberation of the proper NH2 and/or COOH terminus by i20S proteasomes resulting from the combination hydrophobic amino acid, small (and polar) amino acid at P1 and P1′, respectively (hepatitis B core antigen 141–151, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV] pp89, and adeno virus E1B), (b) enhanced generation of TAP-compatible CTL epitope precursors due to increased i20S proteasome activity for the combination hydrophobic amino acid, small (and polar) amino acid at P1 and P1′, respectively (LCMV pp89, LCMV nucleoprotein [NP]), or (c) reduced PGPH activity of i20S proteasomes not destroying the CTL epitope (influenza A NP). However the combination hydrophobic amino acid, small (and polar) amino acid at P1 and P1′ within a CTL epitope can also favor its destruction by i20S proteasomes as shown for a CTL epitope derived from the ubiquitous self-protein RU1.

Table 3.

Correlation between Observed and Predicted Cleavages Preferentially Performed by c20S and i20S Proteasomesa

| Source | MHC restriction | Influence of IFN-γ | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ▾ NAPIL STLPETTVVRRRGRSPR | ||||

| HbcAg 141–151 | HLA-Aw68 | + | 14 | |

| ▿ RGVQI ASNENMD AMDSRTLELR | ||||

| Influenza A NP | H2-Db | + | 35 | |

| ▾▾ LMY DM YPHFMPTNL GPSEKR | ||||

| LCMV pp89 | H2-Ld | + | 8 | |

| ▾▿ KIM RTE RPQASGVYM GNLTAQ | ||||

| LCMV NP | H2-Ld | + | 16 | |

| ▾ YKISKL VNIRNCCYI SGNGAE | ||||

| Adeno E1B | H2-Kb | + | 13 | |

| ▾ TGSTAVPYGSF KHVDTRLQ | ||||

| RUI | HLA-B51 | − | 20 |

The finding that the peptide pool generated by immunoproteasomes differs from the one produced by constitutive proteasomes leads to important biological consequences as also shown by the effect of immunosubunit incorporation on skin graft rejection and CTL induction (Fig. 4). Recently, it was found that dendritic cells and other professional APCs express immunoproteasomes 20. In contrast, most cells outside the lymphoid system harbor mainly constitutive proteasomes, unless they are exposed to inflammatory stimuli. These findings indicate that the peptide pool available to MHC molecules, and thus for presentation to the immune system, differs substantially between professional APCs and nonlymphoid cells. Professional APCs are not only involved in T cell priming, they also play a pivotal role in central and peripheral T cell tolerization 35 36 37. They can tolerize against endogenously expressed antigens, but also against antigens acquired from exogenous sources (cross-tolerization; reference 38). Although these antigens are derived from nonlymphoid cells that only express constitutive proteasomes, tolerance will be induced against self-peptides that are generated by cells expressing immunoproteasomes. During viral infection, virus-infected cells but also neighboring cells will be exposed to inflammatory cytokines, leading to immunoproteasome expression. Because tolerance has been adjusted to the peptide pool expressed by cells harboring immunoproteasomes, self-reactive immune attack is thus reduced to a minimum.

These considerations might also be relevant for induction of CTL immunity against ubiquitously expressed self-proteins. If tolerance to self-proteins was restricted to peptides generated by immunoproteasomes, nonlymphoid cells expressing constitutive proteasomes would display peptides for which no CTL tolerance has been induced. In this respect, it is noteworthy that all CTL epitopes derived from ubiquitous self-proteins (like RU1, Mage-1, gp100, and Melan-A; reference 20) identified thus far are generated less efficiently by immunoproteasomes, whereas presentation of viral epitopes is, in general, enhanced after immunoproteasome expression 8 13 14 15 16.

The combination of MHC class I ligand motifs and constitutive/immunoproteasomal cleavage motifs for T cell epitope prediction will enhance progress in precise manipulation of specific immune responses. For example, it should now be possible to identify new CTL epitopes preferentially generated by constitutive proteasomes (like the RUI epitope). Such peptides are attractive candidates to be used as cancer vaccines, especially if they are derived from antigens that are, for example, overexpressed in tumors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to H. Schild (Schi301/2-2 and SFB 510 C1) and the European Union to H.G. Rammensee (Biomed 95-0263), Merck KgaA (Darmstadt, Germany), and CTL Immunotherapies Corporation (Chatsworth, CA). The research of Dr. R.E.M. Toes has been made possible by a fellowship of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. The Basel Institute for Immunology was founded and is supported by Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: ChT, chymotrypsin; LCMV, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus; LMP, low molecular weight protein; MALDI, matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization; MECL, multicatalytic endopeptidase complex–like; MS, mass spectrometry; NP, nucleoprotein; PGPH, peptidyl-glutamylpeptide-hydrolyzing; TAP, transporter-associated with antigen processing.

R.E.M. Toes and A.K. Nussbaum contributed equally to this work.

References

- Rammensee H.-G., Falk K., Rötzschke O. Peptides naturally presented by MHC class I molecules. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1993;11:213–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.11.040193.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock K.L., Goldberg A.L. Degradation of cell proteins and the generation of MHC class I-presented peptides. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:739–779. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pamer E., Cresswell P. Mechanisms of MHC class I–restricted antigen processing. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1998;16:323–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coux O., Tanaka K., Goldberg A.L. Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;65:801–847. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer W., Fischer M., Krimmer T., Stachon U., Wolf D.H. The active sites of the eukaryotic 20 S proteasome and their involvement in subunit precursor processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25200–25209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dick T.P., Nussbaum A.K., Deeg M., Heinemeyer W., Groll M., Schirle M., Keilholz W., Stevanovic S., Wolf D.H., Huber R. Contribution of proteasomal β-subunits to the cleavage of peptide substrates analyzed with yeast mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:25637–25646. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M., Ditzel L., Löwe J., Stock D., Bochtler M., Bartunik H.D., Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 Angstrom resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boes B., Hengel H., Ruppert T., Multhaup G., Koszinowski U.H., Kloetzel P.M. Interferon γ stimulation modulates the proteolytic activity and cleavage site preference of 20S mouse proteasomes. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:901–909. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groettrup M., Ruppert T., Kuehn L., Seeger M., Standera S., Koszinowski U., Kloetzel P.M. The interferon-γ-inducible 11 S regulator (PA28) and the LMP2/LMP7 subunits govern the peptide production by the 20 S proteasome in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:23808–23815. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaczynska M., Rock K.L., Goldberg A.L. γ-interferon and expression of MHC genes regulate peptide hydrolysis by proteasomes. Nature. 1993;365:264–267. doi: 10.1038/365264a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eleuteri A.M., Kohanski R.A., Cardozo C., Orlowski M. Bovine spleen multicatalytic proteinase complex (proteasome). Replacement of X, Y, and Z subunits by LMP7, LMP2, and MECL1 and changes in properties and specificity. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:11824–11831. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardozo C., Kohanski R.A. Altered properties of the branched chain amino acid-preferring activity contribute to increased cleavages after branched chain residues by the “immunoproteasome”. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:16764–16770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.27.16764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijts A.J., Standera S., Toes R.E.M., Ruppert T., Beekman N.J., van Veelen P.A., Ossendorp F.A., Melief C.J., Kloetzel P.M. MHC class I antigen processing of an adenovirus CTL epitope is linked to the levels of immunoproteasomes in infected cells. J. Immunol. 2000;164:4500–4506. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sijts A.J., Ruppert T., Rehermann B., Schmidt M., Koszinowski U., Kloetzel P.M. Efficient generation of a hepatitis B virus cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope requires the structural features of immunoproteasomes. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:503–514. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hall T., Sijts A., Camps M., Offringa R., Melief C., Kloetzel P.M., Ossendorp F. Differential influence on cytotoxic t lymphocyte epitope presentation by controlled expression of either proteasome immunosubunits or PA28. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:483–494. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz K., van Den B.M., Kostka S., Kraft R., Soza A., Schmidtke G., Kloetzel P.M., Groettrup M. Overexpression of the proteasome subunits LMP2, LMP7, and MECL-1, but not PA28 α/β, enhances the presentation of an immunodominant lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus T cell epitope. J. Immunol. 2000;165:768–778. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaczynska M., Rock K.L., Spies T., Goldberg A.L. Peptidase activities of proteasomes are differentially regulated by the major histocompatibility complex-encoded genes for LMP2 and LMP7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:9213–9217. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craiu A., Akopian T., Goldberg A., Rock K.L. Two distinct proteolytic processes in the generation of a major histocompatibility complex class I-presented peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:10850–10855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltze L., Dick T.P., Deeg M., Pommerl B., Rammensee H.G., Schild H. Generation of the vesicular stomatitis virus nucleoprotein cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope requires proteasome-dependent and -independent proteolytic activities. Eur. J. Immunol. 1998;28:4029–4036. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4029::AID-IMMU4029>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morel S., Levy F., Burlet-Schiltz O., Brasseur F., Probst-Kepper M., Peitrequin A.L., Monsarrat B., Van Velthoven R., Cerottini J.C., Boon T. Processing of some antigens by the standard proteasome but not by the immunoproteasome results in poor presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity. 2000;12:107–117. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum A.K., Dick T.P., Keilholz W., Schirle M., Stevanovic S., Dietz K., Heinemeyer W., Groll M., Wolf D.H., Huber R. Cleavage motifs of the yeast 20S proteasome β subunits deduced from digests of enolase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:12504–12509. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedderburn R.W.M. Quasi-likelihood functions, generalized linear models, and the Gauss-Newton method. Biometrika. 1974;61:439–447. [Google Scholar]

- Fehling H.J., Swat W., Laplace C., Kuhn R., Rajewsky K., Muller U., von Boehmer H. MHC class I expression in mice lacking the proteasome subunit LMP-7. Science. 1994;265:1234–1237. doi: 10.1126/science.8066463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold D., Wahl C., Faath S., Rammensee H.G., Schild H. Influences of transporter associated with antigen processing (TAP) on the repertoire of peptides associated with the endoplasmic reticulum–resident stress protein gp96. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:461–466. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies T., Bresnahan M., Bahram S., Arnold D., Blanck G., Mellins E., Pious D., DeMars R. A gene in the human major histocompatibility complex class II region controlling the class I antigen presentation pathway. Nature. 1990;348:744–747. doi: 10.1038/348744a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMars R., Rudersdorf R., Chang C., Petersen J., Strandtmann J., Korn N., Sidwell B., Orr H.T. Mutations that impair a posttranscriptional step in expression of HLA-A and -B antigens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:8183–8187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.8183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brendel V., Bucher P., Nourbakhsh I.R., Blaisdell B.E., Karlin S. Methods and algorithms for statistical analysis of protein sequences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:2002–2006. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin T.A., Nandi D., Cruz M., Fehling H.J., Kaer L.V., Monaco J.J., Colbert R.A. Immunoproteasome assemblycooperative incorporation of interferon γ–inducible subunits. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:97–104. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson E., Roopenian D. Minor histocompatibility antigens. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1997;9:655–661. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gileadi U., Moins-Teisserenc H.T., Correa I., Booth B.L., Jr., Dunbar P.R., Sewell A.K., Trowsdale J., Phillips R.E., Cerundolo V. Generation of an immunodominant CTL epitope is affected by proteasome subunit composition and stability of the antigenic protein. J. Immunol. 1999;163:6045–6052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimbara N., Ogawa K., Hidaka Y., Nakajima H., Yamasaki N., Niwa S., Tanahashi N., Tanaka K. Contribution of proline residue for efficient production of MHC class I ligands by proteasomes. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23062–23071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.36.23062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuttler C., Nussbaum A.K., Dick T.P., Rammensee H.G., Schild H., Hadeler K.P. An algorithm for the prediction of proteasomal cleavages. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;298:417–429. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miconnet I., Servis C., Cerottini J.C., Romero P., Levy F. Amino acid identity and/or position determines the proteasomal cleavage of the HLA-A*0201-restricted peptide tumor antigen MAGE-3271-279. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:26892–26897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000701200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltze L., Nussbaum A.K., Sijts A., Emmerich N.P.N., Kloetzel P.M., Schild H. The function of the proteasome system in MHC class I antigen processing. Immunol. Today. 2000;21:317–319. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(00)01665-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauter B., Albert M.L., Francisco L., Larsson M., Somersan S., Bhardwaj N. Consequences of cell deathexposure to necrotic tumor cells, but not primary tissue cells or apoptotic cells, induces the maturation of immunostimulatory dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:423–434. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F.P., Platt N., Wykes M., Major J.R., Powell T.J., Jenkins C.D., MacPherson G.G. A discrete subpopulation of dendritic cells transports apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells to T cell areas of mesenteric lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:435–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinman R.M., Turley S., Mellman I., Inaba K. The induction of tolerance by dendritic cells that have captured apoptotic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;191:411–416. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurts C., Kosaka H., Carbone F.R., Miller J.F., Heath W.R. Class I-restricted cross-presentation of exogenous self-antigens leads to deletion of autoreactive CD8+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:239–245. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.2.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]