T Cells Compete for Access to Antigen-Bearing Antigen-Presenting Cells (original) (raw)

Abstract

These studies tested whether antigenic competition between T cells occurs. We generated CD8+ T cell responses in H-2b mice against the dominant ovalbumin epitope SIINFEKL (ova8) and subdominant epitope KRVVFDKL, using either vaccinia virus expressing ovalbumin (VV-ova) or peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. CD8+ T cell responses were visualized by major histocompatibility complex class I–peptide tetrameric molecules. Transfer of transgenic T cells with high affinity for ova8 (OT1 T cells) completely inhibited the response of host antigen-specific T cells to either antigen, demonstrating that T cells can directly compete with each other for response to antigen. OT1 cells also inhibited CD8+ T cell responses to an unrelated peptide, SIYRYGGL, providing it was presented on the same dendritic cells as ova8. These inhibitions were not due to a more rapid clearance of virus or antigen-presenting cells (APCs) by the OT1 cells. Rather, the inhibition was caused by competition for antigen and antigen-bearing cells, since it could be overcome by the injection of large numbers of antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. These results imply that common properties of T cell responses, such as epitope dominance and secondary response affinity maturation, are the result of competitive interactions between antigen-bearing APC and T cell subsets.

Keywords: T cell, competition, tetramer, antigen-presenting cell, dendritic cell

Introduction

The phenomenon of antigenic competition, in which immune responses to one determinant are inhibited by simultaneous exposure to antigens on the same or different molecules, has been known since at least the turn of the century 1 2 3 4. Much of the early work on competition focused on inhibition of antibody responses to various haptens. In recent years, many of the mysteries of B cell competition have been elucidated and shown to be the consequence of somatic hypermutation and affinity maturation 5 6.

T cell competition for antigen has also been suggested, usually in reference to T cell responses to subdominant or cryptic epitopes that appear to be inhibited by responses to other, apparently more powerful antigens 7 8 9 10 11. Many of the earlier results have been attributed to differential processing and competition for loading into a limited number of cell surface MHC molecules between various peptide antigens 8 9 12. However, not all of epitope dominance can be explained in terms of peptide loading and affinity for MHC 7, and there are data to suggest that T cells responding to one antigen can actively interfere with T cells responding to another 10 11.

More recently, the study of secondary T cell responses has suggested a previously unpredicted mechanism for T cell competition. Several groups have recently demonstrated that, upon secondary challenge, the average affinity for peptide plus MHC of the receptors (TCRs) on the responding T cells increases 13 14 15. This occurs in the absence of somatic mutation, the phenomenon that drives affinity maturation of B cell responses 5 16. The process appears to be due to a preferential outgrowth of the higher affinity T cells present within the pool of primary responders, suggesting that the higher affinity cells have a competitive advantage for responding to antigen. Therefore, T cells must compete for antigen at some level.

To study this problem, we developed a model system with which we could directly observe competition between subsets of CD8+ T cells and determine the parameters dictating that competition. Our data demonstrate that T cell competition can occur at the level of access to the limited number of antigen-bearing APCs. The data we describe are most consistent with the “interference” model 10 11 whereby a particular set of T cells physically excludes the access of another to antigen-bearing APCs.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

C57BL/6J (B6) and B6.PL-Thy1a/Cy (B6.PL) 6–12-wk-old female mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Mice on the B6 background, transgenic for a TCR specific for an ovalbumin peptide bound to Kb (OT1 transgenic mice [17, 18]) were provided by Dr. Terry Potter (National Jewish Medical and Research Center). Mice of this strain were used at 6–10 wk of age. No significant differences were seen when the OT1 mice and the B6.PL recipients were male rather than female. B6 mice expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) under the control of the ubiquitin promoter, UBI-GFP, were made in the National Jewish Microinjection Facility using constructs by B. Schaefer. The majority of cells in these animals, including the dendritic cells (DCs) shown in this paper, express high levels of GFP (Schaefer, B., unpublished results).

Antibodies and Tetramers.

Anti-CD8–allophycocyanin, CD44-FITC, Thy1.2-FITC, B220-cychrome, IAb-biotin, and streptavidin-cychrome were all purchased from BD PharMingen. Kb covalently linked by the COOH terminus to a peptide tag that is a substrate for BirA was produced in insect cells, biotinylated, and bound to phycoerythrin-streptavidin (SA-PE) as described previously 19 with the following modifications. Hi5 insect cell cultures were coinfected with 5–10 ml of secondary Kb/BirA and mouse β2-microglobulin (β2M) baculovirus stocks. 6–8 d later, the soluble Kb molecules were purified on an S19.8 (anti-β2M) affinity column. Singly biotinylated Kb/β2M molecules (biotinylated on the COOH terminus peptide tag by the addition of the BirA enzyme) were then combined in the appropriate ratios with SA-PE (Rockland), and the resulting Kb tetramer was purified on a sizing column. 5–10 molar excess of SIINFEKL (ova8, ovalbumin residues 257–264), KVVRVDKL (ovalbumin residues 55–62), or SIYRYYGL (which activates cells bearing the 2C TCR in the context of Kb 20) peptides were added directly to the Kb–SA-PE tetramer for at least 30 min at 4°C. The tetramers were then used to stain cells. Kb tetramers bearing an irrelevant peptide, usually SIYRYYGL (i.e., same MHC, wrong peptide), were used to establish the background staining of experimental samples. Each batch of Kb/ova8 tetramer was tested and normalized for binding to naive OT1 T cells before use in experiments.

Virus Infection.

Vaccinia virus (VV) was propagated in and titrated by plaque assay on cultured 143B osteosarcoma cells as described previously 21. Mice were challenged with 2 × 106 PFU VV encoding ovalbumin (VV-ova 22) or flu nucleoprotein (VV-NP 22) as described previously 21. In some cases, viral growth in the animals was assessed by measuring virus titers in their spleens and ovaries 5 and 7 d after infection.

Cell Preparation and Analysis.

DCs were prepared from B6 and UBI-GFP mice. Bone marrow was removed from the major leg bones and T and B cell depleted with antibodies and rabbit complement. The cells were cultured in 6-well plates in 1,000 U/ml of GM-CSF (from the B78Hi/GMCSF.1 cell line 23 provided by Dr. Hyam Levitsky, Johns Hopkins, Baltimore, MD) and IL-4 in complete suspension MEM (SMEM) medium. Nonadherent cells were removed from the cultures on day 2, centrifuged, and the resulting conditioned medium was put back on the adherent cells (DCs and precursors) in conjunction with 50% fresh medium. Every 2 d, 2 ml of fresh GM-CSF/IL-4 medium was added to each well and the cells were given 1 μg/ml of LPS on day 6 or 7 to induce the maturation of the DC precursors. The day after LPS addition, the cells were incubated with 5 ng/ml peptides for 2.5 h, washed, and injected in various numbers intravenously into B6.PL recipients. Staining the DCs before injection with 25D1.16 24, an antibody that recognizes the Kb molecule only when in complex with the ova8 peptide, demonstrated that, after incubation with the ova8 peptide, this peptide was uniformly distributed on all of the cultured DCs (data not shown).

In most experiments, T cells were isolated from spleen and ovaries by homogenization of the tissue using a Dounce homogenizer or by passing the tissue through nylon screens. Red blood cells were lysed by the addition of a buffered ammonium chloride solution, and the nucleated cells were resuspended in complete SMEM medium. In some cases, DCs were purified from spleen suspensions by incubation for 45 min in 5 μg/ml collagenase D (25; Boehringer) in Click's medium with 2% fetal bovine serum at 37°C. An equal volume of 0.1 mM EDTA in Click's medium was then added for 5 min, and the remaining tissue was passed through nylon mesh. This was then washed with 5 mM EDTA in Click's medium and eventually resuspended in either Click's medium with 5 mM EDTA (to prevent clumping) for DC staining or in complete SMEM medium for T cell staining.

Tetramer staining was performed as described previously 15. In brief, 2 × 106 pooled spleen and ovary cells were incubated in 100 μl of FACS buffer with 5–10 μg/ml of tetramer in 96-well plates at 37°C for 2 h. The remaining antibodies were then added and further incubated for 30–45 min before washing and resuspending in FACS buffer for analysis.

Four-color FACS® data were collected on a FACSCalibur™ flow cytometer and analyzed using CELLQuest™ software (Becton Dickinson). FACS® data were usually analyzed by gating on events in the lymphocyte forward/side scatter bit maps that were CD8+ and IAb− and/or B220−. Kb/ova8 tetramer staining of cells from mice injected with a non–ovalbumin-bearing/expressing stimulus (VV-NP–pulsed or non–peptide-pulsed DCs), or the use of an irrelevant tetramer to stain experimental cells was used to assess background tetramer staining. No significant differences were seen between the two methods of background assessment.

Results

Antigen-specific T Cells Inhibit the Primary Responses to the Same Antigen.

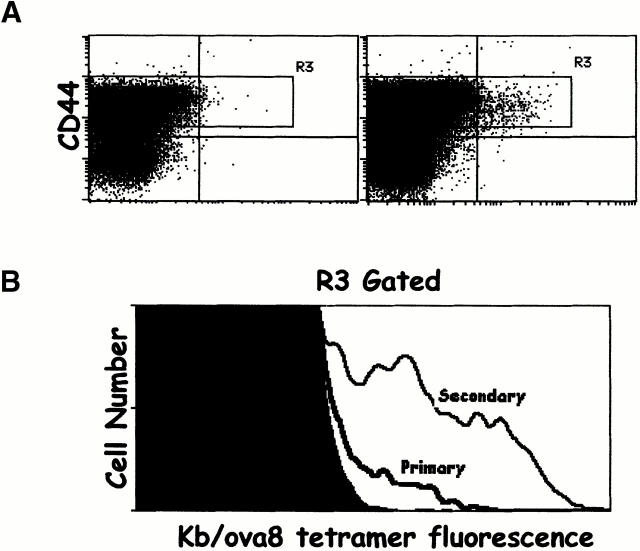

CD8+ T cells specific for Kb bound to SIINFEKL (ova8), the major ovalbumin peptide presented by Kb, were primed by immunizing mice with VV-ova. CD8+ T cells specific for Kb/ova8 were detected using SA-PE bound to this MHC–peptide combination. After intravenous challenge of mice with 2 × 106 PFU of VV-ova, the peak of the ova8-specific CD8+ T cell response was between days 9 and 12 (Fig. 1 A, and data not shown). The ova8-specific cells at this time point expressed high levels of CD44 (Fig. 1 A) and very late antigen 4 (VLA-4) and low levels of L-selectin (data not shown). Secondary challenge of these mice 25 d after primary immunization resulted in a more rapid and greater magnitude of expansion of the ova8-specific T cells seen on day 5 after secondary challenge (Fig. 1 B). In addition, secondary challenge caused a significant outgrowth of T cells with a higher level of fluorescence after staining with Kb/ova8 tetramer (Fig. 1 B). Staining of the cells with anti-CD3 demonstrated that this increase in fluorescence was not due to an increase in TCR levels (data not shown). As previous studies have indicated 13 14 15, this increased staining suggests that these cells possessed a higher intrinsic affinity for antigen. While formally this increased binding to tetramer may be due to altered mobility or geometric distribution of TCR or to increased CD8 coreceptor function, in our hands the level of tetramer binding, when corrected for TCR levels, correlates most consistently with an increase in TCR affinity for antigen–MHC 26.

Figure 1.

Tetramers can detect ovalbumin-specific T cells in VV-ova–immunized mice. B6 mice were immunized with 2 × 106 PFU VV-NP or VV-ova intravenously. 25 d later, some of the VV-ova–primed mice were reexposed to the same virus. 9 d after the primary infection or 5 d after the secondary infection, spleen and ovary cells were isolated from the animals, pooled, and stained with the Kb/ova8 tetramer and anti-CD8 as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Cells from mice infected once with VV-NP (left) or VV-ova (right). (B) Cells from mice undergoing primary or secondary responses to VV-ova. Background staining is from VV-NP–infected mice stained with the Kb/ova8 tetramer.

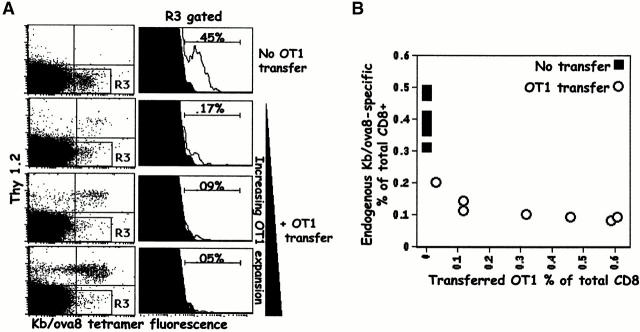

If T cells compete with each other during responses to antigen, we reasoned that the transfer of Kb/ova8-specific T cells into mice before VV-ova exposure might inhibit the response of the endogenous T cells. To test this idea, B6 (Thy1.2+) Kb/ova8-specific OT1 transgenic T cells were transferred to B6.PL (Thy1.1+) mice. The recipients were then challenged with VV-ova. Cells from the transferred mice were stained with anti-Thy1.2 and Kb/ova8 tetramer, and the responses of both transferred and endogenous Kb/ova8-specific T cells were thus measured and compared (Fig. 2). The transferred OT1 cells strongly inhibited increases in the numbers of Kb/ova8-specific endogenous T cells (Fig. 2 A). This inhibition was proportional to the expansion of the transferred OT1 cells, though only a small expansion of the transferred cells almost completely inhibited the endogenous T cell response (Fig. 2 B).

Figure 2.

Transferred OT1 cells compete against the primary response of endogenous Kb/ova8-specific CD8+ T cells. B6.PL mice, with or without the transfer of 0.2–1 × 106 B6 OT1 transgenic T cells, were immunized with VV-ova as in the legend to Fig. 1. 9 d after infection, pooled ovary and spleen cells were stained with the Kb/ova8 tetramer as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Data were analyzed by gating on CD8+class II− events. The dot plots were additionally gated on all Thy1.2− events (R3 gate) to generate the histograms (right). The percentage given above the marker is the percentage of the total Thy1.2−CD8+ T cells staining positively for tetramer binding. Background (solid histogram) is from irrelevant tetramer staining of experimental cells. (B) Data pooled from two separate experiments demonstrating the inverse relationship between the expansion of the transferred cells and the expansion of the endogenous cells. The y-axis is the percentage of endogenous tetramer-staining cells out of all endogenous (Thy1.2−) cells. The x-axis is the percentage of transferred (Thy1.2+) cells out of both Thy1.2+ and Thy1.2− cells. The data shown are representative of six separate experiments.

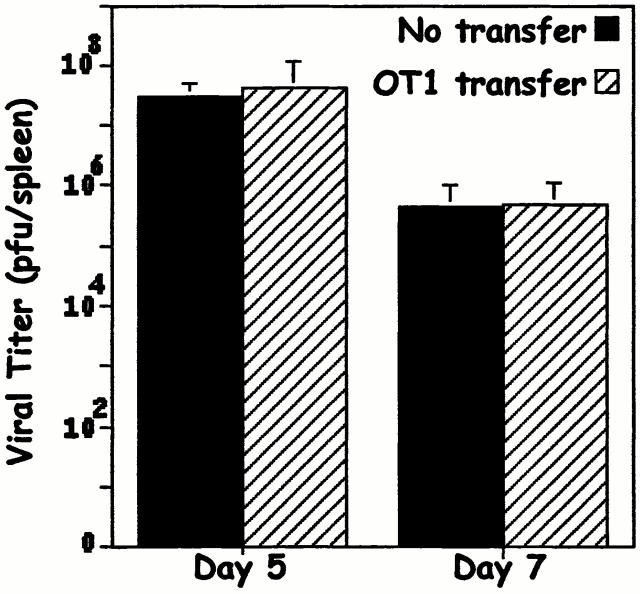

Inhibition by Antigen-specific T Cells Is Not Due to Reductions in Antigen Levels.

One concern was that the reduction of the endogenous T cell response in the transferred mice was due to a more rapid elimination of virus, and therefore elimination of antigen, in mice receiving the transferred cells compared with nontransferred controls. To find out whether this was true, mice with and without transferred OT1 cells were challenged with VV-ova and viral titers in spleen and ovary were measured. The data demonstrate that viral titers in transferred mice were the same as those in nontransferred controls (Fig. 3). This was true even if the numbers of OT1 cells transferred were much higher than those required to suppress the endogenous T cell response (compare data in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). Thus, the failure of the endogenous T cell response in mice given OT1 cells was not due to a more rapid clearance of antigen.

Figure 3.

Transfer of OT1 cells does not cause accelerated clearance of VV-ova. B6.PL mice with or without transfer of 106 B6 OT1 transgenic T cells were immunized with VV-ova as in the legend to Fig. 1. On days 5 and 7 after infection, viral plaque assays were performed on pooled spleen and ovary tissue. The data shown are from triplicate titers of triplicate mice per time point. As a control, a small number of T cells were stained with tetramer from the transferred group of mice to insure that the transferred cells had indeed responded to the viral challenge (data not shown).

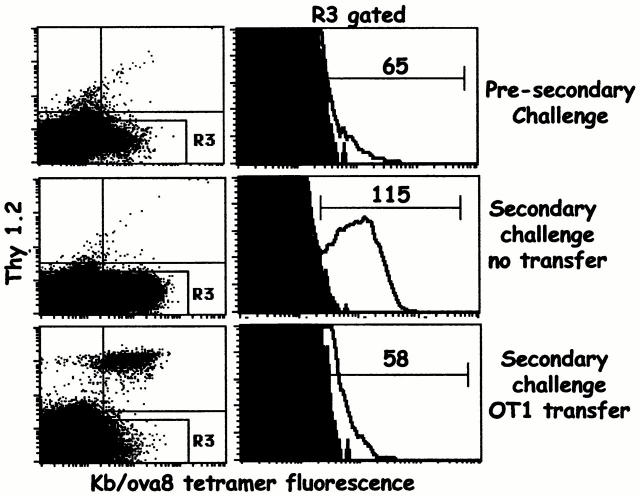

Transfer of OT1 Cells Inhibits Secondary Responses to Antigen.

We next tested whether transferred OT1 cells could inhibit the response of primed T cells. B6.PL mice were challenged with VV-ova and 25 d later were rechallenged with the same virus with or without transfer of OT1 transgenic T cells. The number of transferred cells was selected such that they would be in approximately the same numbers in the recipient as the endogenous Kb/ova8-specific memory cells (∼0.25% of all CD8+ T cells; data not shown). Nontransferred mice demonstrated significant expansion and affinity maturation of the endogenous T cell population after secondary challenge. However, the expansion and affinity maturation of the established endogenous memory T cells were strongly inhibited by the transferred cells (Fig. 4). Given the high affinity of the OT1 TCR for antigen (1–6 μM), these data suggest that the affinity of a given T cell enhances its ability to compete for access to, and expansion from, antigen stimulation. It should be noted that the low level of tetramer staining of the OT1 cells after activation is due primarily to a high degree of receptor downregulation (see Discussion).

Figure 4.

Transferred OT1 cells compete against the secondary response of endogenous Kb/ova8-specific CD8+ T cells and inhibit affinity maturation. 25 d after initial VV-ova immunization, B6.PL mice were transferred with 3 × 106 OT1 T cells and rechallenged with VV-ova. This response was compared with that of B6.PL mice given a secondary VV-ova immunization without OT1 T cell transfer. The data were analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. The numbers above the markers in the histograms are the mean fluorescence intensity of the tetramer-staining cells. The data presented are representative of three separate experiments.

T Cell Inhibition Is Not Antigen Specific.

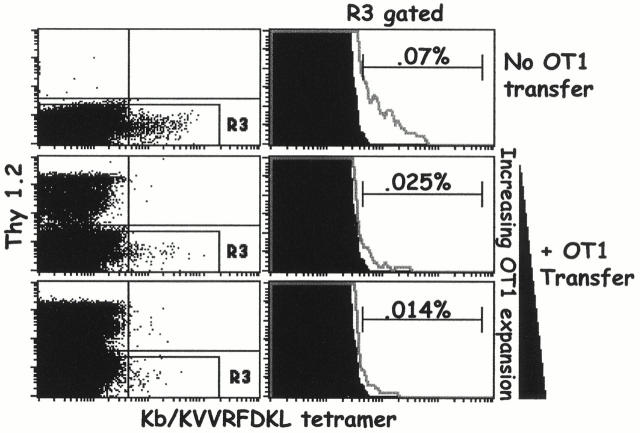

There are several explanations for the inhibitory effect of the transferred cells. For example, they might compete with endogenous cells for access to the limited number of Kb/ova8 complexes on the APCs. Alternatively, they might compete for access to APCs in an antigen-nonspecific way. Finally, they might compete for factors, such as growth-promoting cytokines, that are unrelated to APC function. To find out whether the transferred cells were inhibiting access to the specific ligand, Kb/ova8, we tested whether or not they could inhibit responses to a different antigen. We chose to study responses to Kb bound to the subdominant ovalbumin peptide, KVVRFDKL. A previous report demonstrated that the dominance of the ova8 epitope is not due to a lack of subdominant-specific T cells in the repertoire but rather because the dominant epitope has a higher affinity for MHC binding than the subdominant epitope does and is therefore more efficiently presented 12. The transfer of OT1 cells should not affect this difference. Mice were infected with VV-ova, and Kb/ KVVRFDKL-specific T cells were detected using Kb tetramers made with the KVVRFDKL peptide. A small population of KVVRFDKL-specific T cells was detectable at ∼1/5–1/10 of the numbers of the Kb/ova8-specific population in VV-ova–infected mice (Fig. 2 and Fig. 5). Transfer of OT1 cells did indeed inhibit the response to the subdominant epitope (Fig. 5). Transfer of T cells specific for a lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus peptide bound to Db did not reduce the endogenous responses to Kb/ova8 in mice primed with VV-ova (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Competition of OT1 T cells with endogenous T cells is not antigen specific. B6.PL mice, with and without transfer of 5 × 105 OT1 T cells, were immunized with VV-ova intravenously. 9 d after the primary infection, spleen and ovary cells were isolated from the animals, pooled, and stained with the minor ovalbumin epitope Kb/KVVRDKL tetramer. Cells were analyzed as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Background staining was determined by irrelevant tetramer staining of experimental cells.

Non–Antigen-specific Competition Occurs Only When the Different Epitopes Are Presented on the Same APC.

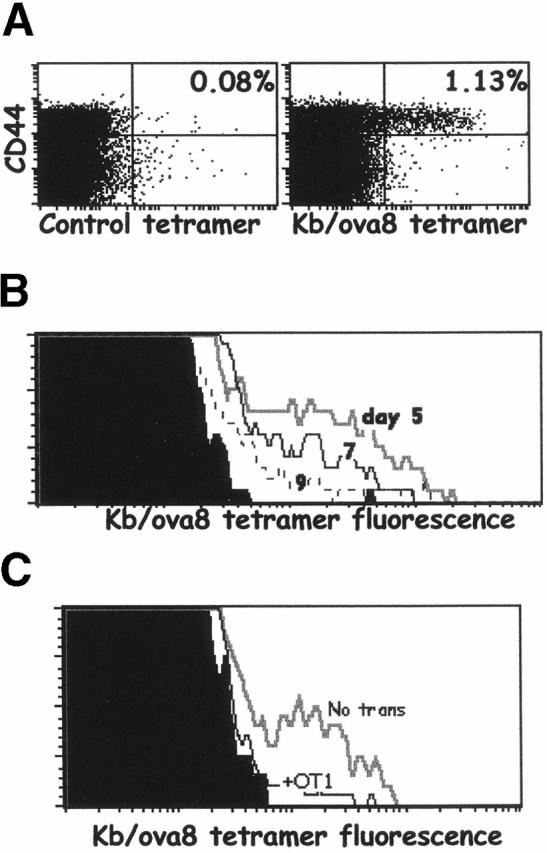

These experiments showed that, in order to inhibit endogenous T cell proliferation, the transferred cells must be activated, but need not be recognizing the same antigen as the inhibited cells. The transferred cells may therefore be operating either by restricting access to APCs in an antigen-nonspecific fashion, or by competing for some other limiting factor(s) such as cytokines. If the transferred cells are restricting access to the APCs, then we predicted that this non–antigen-specific competition would occur only when different epitopes are presented on the same APC. In contrast, if the cells are competing for soluble factors, then the transferred cells may be able to compete with cells of other specificities as long as they are activated at the same time but not necessarily by the same APC. To test this possibility, we changed our priming stimulus to a challenge with in vitro–cultured and peptide-pulsed DCs. Peptide-pulsed DCs stimulated a vigorous response (Fig. 6 A) that peaked around day 5 after DC injection (Fig. 6 B). It is interesting to note that the distribution of tetramer staining on T cells in response to DC challenge was broader than that seen in response to VV-ova infection (compare Fig. 2 and Fig. 6). This suggests that the immunization with DCs pulsed with a single peptide epitope generated T cells with a more diverse range of affinities than did immunization with a multiepitope-encoding virus infection (see Discussion). Transferred OT1 cells inhibited the endogenous response to limited numbers of DCs injected (Fig. 6 C), indicating that competition with the endogenous T cells was still observable under this priming regimen.

Figure 6.

Peptide-pulsed DCs induce a vigorous CD8+ T cell response that can be inhibited by OT1 T cell transfer. Bone marrow was removed from the major leg bones of B6 mice, T and B cell depleted, and cultured with IL-4 and GM-CSF for 8 d. ova8 peptide was added to the cultures at 5 μg/ml for 2 h at 37°C. The resulting DCs were harvested and injected intravenously into B6 recipients at 106/mouse. On days 5, 7, and 9 after DC injection, the spleens were harvested and stained with Kb/ova8 tetramer. (A) Dot plots from the day 5 time point gated on live, CD8+class II− events. Companion stains showed the Kb/ova8 tetramer staining cells to also be predominantly blasts and CD25+ at only the day 5 time point, and L-selectinlo and CD44hi at all time points (data not shown). (B) Tetramer staining histograms of live, CD8+class II−CD44hi gated events of spleen cells from DC-challenged mice analyzed at the times indicated after initial DC challenge. (C) Mice immunized as in A with (+OT1) and without (No trans) the transfer of 5 × 105 OT1 T cells.

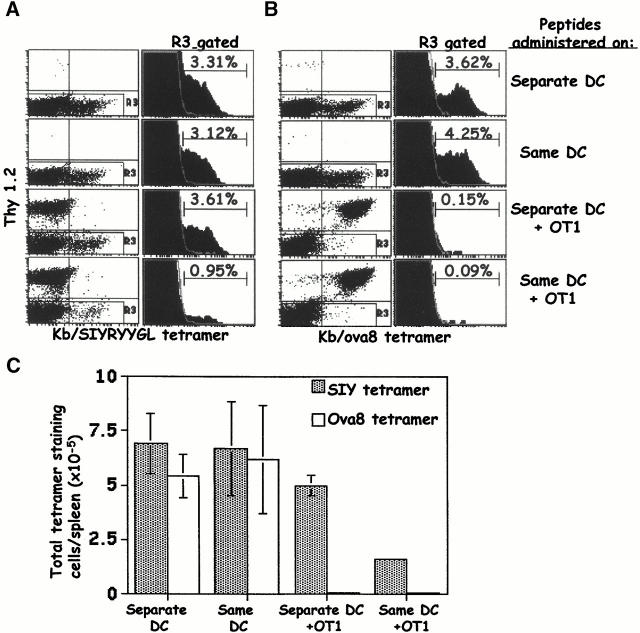

We next used two different peptide epitopes in the DC immunizations to determine the importance of the localization of each epitope for the degree and specificity of competition. Cultured DCs were pulsed with either the ova8 peptide, the SIYRYYGL peptide 20, or both peptides together. Mice were injected with equal numbers of DCs bearing each epitope separately or with DCs bearing both epitopes simultaneously. The DCs were injected into mice with or without the transfer of OT1 T cells, and 5 d later the CD8+ T cell responses to each epitope were assessed by staining the cells with either tetramer.

In the absence of the OT1 T cells, mice injected with single or double peptide–pulsed DCs generated vigorous responses against both peptides (Fig. 7A and Fig. B, top two rows). When mice were immunized with two sets of DCs, each pulsed with one peptide, in the presence of OT1 cells, the endogenous response against the SIYRYYGL peptide was not affected while the ova8-specific response was severely inhibited (Fig. 7A and Fig. B, third row). However, when mice were immunized with DCs bearing both peptides simultaneously, the transferred OT1 cells inhibited the endogenous response to both peptides (Fig. 7A and Fig. B, bottom row). The competition by OT1 cells with T cells responding to either peptide can be seen in terms of both the percentage (Fig. 7A and Fig. B) and the total number of responding tetramer-staining cells (Fig. 7 C). This inhibition occurred against each peptide to different degrees, with the SIYRYYGL response inhibited 3–5-fold and the ova8 response inhibited >100-fold (Fig. 7 C).

Figure 7.

Non–antigen-specific competition of OT1 T cells is dependent on the copresentation of epitopes on a common APC. B6.PL mice with and without the transfer of 1–2 × 106 OT1 cells were challenged intravenously with antigen-pulsed DCs in two different ways: 1.5 × 106 0.5 μg/ml ova8-pulsed DCs plus 1.5 × 106 0.5 μg/ml SIYRYYGL-pulsed DCs (Separate DC); or 1.5 × 106 DCs pulsed with both peptides (Same DC). 5 d after DC challenge, the spleens were harvested and the cells were stained with either the Kb/SIYRYYGL tetramer (A) or the Kb/ova8 tetramer (B). The data for the dot plots were gated on live, CD8+class II− events, and the data for the histograms were further gated on Thy1.2− events (R3). The percentages given are the percentages of the total endogenous CD8+ T cell population. The total cell number was multiplied by the percent CD8+ in each sample, which was then multiplied by the percentage of tetramer-staining events in A and B to give the total number of tetramer-staining cells in each sample (C). The average and standard deviation were calculated from four mice per group.

Thus, the transferred OT1 cells are able to compete with endogenous T cells responding either to the same peptide or to a different peptide, provided that the OT1 cells can react with the same APCs as the endogenous T cells. The fact that endogenous responses to the peptide recognized by OT1 cells are more strongly inhibited than responses to an unrelated peptide on the same APC indicated that OT1 cells might be inhibiting in two different ways. They appear to be competing simply for access to DCs, thus inhibiting responses to any peptide borne by the DCs with which they are reacting. In addition, the OT1 cells appear to be even more severely inhibiting responses to the very peptide they themselves recognize. This suggests that competition between T cells can occur both at the level of access to the entire APC and at the level of access to peptide, and that the competition for the latter is more efficient than for the former.

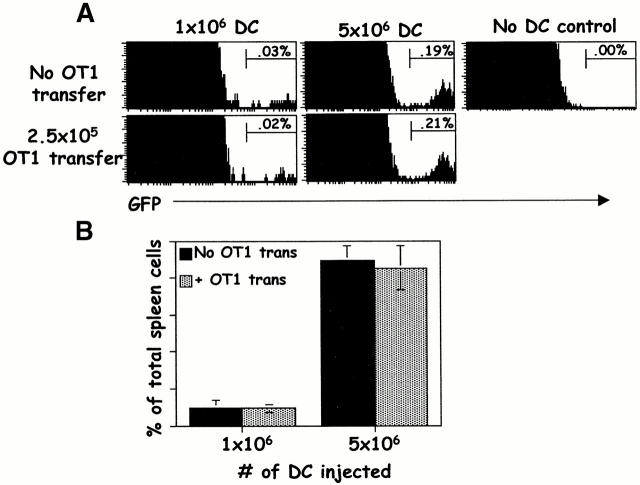

Competing T Cells Do Not Kill Antigen-presenting DCs.

Since the transferred OT1 cells were CTL precursors, it was possible that they inhibited the endogenous T cells by prematurely killing antigen-bearing APCs. To determine the fate of the injected DCs, we cultured bone marrow from mice transgenic for GFP driven by the ubiquitin promoter (UBI-GFP). Nearly all of the cells from UBI-GFP mice, including the DCs, fluoresce green (Schaefer, B., unpublished results). B6.PL mice were immunized with GFP+ ova8-pulsed DCs, with and without transfer of OT1 cells, and 5 d later the spleens were removed and treated with collagenase D to release the DCs 25. FACS® analysis showed that the recovery of GFP+ DCs was unaffected by simultaneous transfer of OT1 cells (Fig. 8A and Fig. B), despite the strong response of the Kb/ova8-specific endogenous or transferred cells (see Fig. 9). Thus, antigen-presenting DCs were not more rapidly cleared in OT1 transferred mice. It should be noted that ova8-specific T cells did not achieve effector function, with respect to lytic activity or IFN-γ secretion, until day 7 after DC injection (data not shown). Therefore clearance of the injected DCs by CD8+ T cell lytic function could not have occurred at the day 5 time point.

Figure 8.

Mice given OT1 T cells do not clear antigen-bearing DCs more rapidly than nontransferred mice. B6.PL mice with and without transfer of 2.5 × 105 OT1 T cells were challenged with increasing numbers of UBI-GFP bone marrow DCs pulsed with 5 ng/ml of ova8 peptide. DCs from the UBI-GFP mice were cultured as in the legend to Fig. 6. 5 d later, splenic DCs were isolated by collagenase treatment and assessed for the presence of GFP+ events. (A) GFP histograms of mice with and without transfer of OT1 cells. All GFP+ cells were also class II+ (not shown). (B) Percentage of GFP+ events of total spleen cells as shown in A, expressed as the average and standard deviation from three mice per group.

Figure 9.

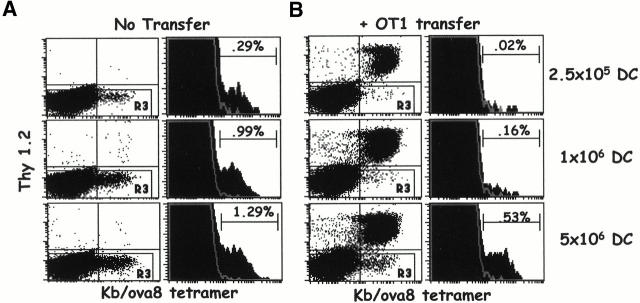

OT1 T cells compete with endogenous T cells for access to DCs. B6.PL mice with and without the transfer of 2.5 × 105 OT1 cells were challenged intravenously with B6 bone marrow DCs pulsed with 5 ng/ml of ova8 peptide. 5 d later, spleen cells were stained with tetramer as in the legend to Fig. 2. (A) Nontransferred B6.PL response to increasing numbers of DCs injected. The dot plots are gated on CD8+class II− events. The histograms were further gated on Thy1.2− (gate R3) events. (B) OT1-transferred B6.PL response to increasing numbers of DCs injected. Gating strategy as in A. (C) The average and standard deviation of endogenous T cell percentages from OT1-transferred and nontransferred mice, three mice per treatment.

Competition by T Cells Is Prevented by Increases in Antigen-presenting DCs.

From these experiments, we concluded that the transferred OT1 cells competed for access to some APC-related factor to the exclusion of the endogenous T cells. If this were correct, then we predicted that it should be possible to elevate the number of antigen-bearing APCs to a level above which the transferred cells could no longer effectively out-compete the endogenous T cells. To test this prediction, ova8-pulsed DCs were again injected in increasing numbers into B6.PL mice with or without transfer of a small number of OT1 T cells.

In the absence of OT1-transferred cells, there was a vigorous endogenous response that increased in magnitude as the number of priming DCs was increased (Fig. 9 A). Transferred OT1 cells inhibited the response of the endogenous T cells when the mice were challenged with small numbers of DCs (Fig. 9 B, top). However, as the numbers of DCs were increased, the endogenous response became readily observable (Fig. 9 B). These results show that transferred OT1 cells inhibited the response of endogenous T cells to antigen by competing for access to the antigen-presenting DCs.

Discussion

The data presented here show that CD8+ T cells can compete with each other during responses to antigen. The competition is alleviated by increasing the numbers of APCs in the animal; hence, it involves some aspect of T cell–APC interaction. However, successful competition does not require that the T cells be responding to the same antigen, nor does it involve killing of the APCs. Thus, competition may be due to limited availability of some soluble factor made by DCs, or limited accessibility to molecules such as MHC or costimulatory proteins on the surface of the DCs. These data agree remarkably well with work from K. Karre's group on the inhibitory effects of responses to major epitopes against responses to minor epitopes 10 11. Our experimental system has the advantage of being able to identify and quantify competing subsets of antigen-specific T cells, as well as the antigen-bearing APCs, directly ex vivo.

The conclusion that antigen-bearing APCs are limiting is surprising, especially in the experiments described here in which mice were immunized with VV-ova. During infection, very high titers of VV are produced, demonstrating that the animal contains plenty of antigen (Fig. 3). At first sight, this suggests that antigen presentation should not be limiting. However, most of the cells infected by VV are epithelial in nature. Not being epithelial in lineage, APCs such as DCs are probably not directly infected by VV. This idea is supported by the fact that we have never seen expression of GFP in the APCs of mice infected with a VV coding for GFP (data not shown), suggesting that APCs must acquire VV epitopes indirectly. Therefore, presentation of antigens encoded by VV to naive T cells within the secondary lymphoid tissue may indeed be limiting, even in animals experiencing fulminant VV production.

Most viruses used experimentally, such as lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and influenza, demonstrate strong dominance of their CD8+ T cell responses towards a limited number of epitopes despite a potential abundance of diverse epitopes from these viruses. This epitope dominance has been shown to be due in part to differences in processing and loading of the peptides into class I 8 9 12. However, recent work by Chen et al. demonstrated that some of these epitopes do not appear to have significant differences in their levels of presentation 7. Our data suggest that an additional reason for epitope dominance may be competition of T cells specific for one antigen with T cells with other specificities. Consistent with this is the fact that preimmunization with a subdominant epitope results in a loss of its subdominant status upon subsequent viral infection 7 27 28. Presumably, generation of a large number of T cells specific for the subdominant epitope allows them to compete more effectively for access to APCs with cells specific for the traditionally more dominant epitope. It is interesting to note that our model predicts that if primary infection leads to a significant immunodominance of a given epitope, then that epitope is likely to dominate the secondary response to an even greater extent due to the competitive advantage of sheer numbers of epitope-specific cells. This phenomenon has been observed in our experimental system (data not shown) and others 7, and demonstrates another situation in which competition could play a role in tailoring T cell responses.

The clone of OT1 T cells was produced after several in vivo and in vitro challenges with antigen 17 18, and the OT1 TCR has a high affinity for antigen (1–6 μM) 29 30. It should be noted that the tetramer fluorescence of the OT1 cells in primed mice at times appears similar to the tetramer fluorescence of some of the endogenous T cells (see Fig. 2, Fig. 4, and Fig. 8). This does not mean that these T cells have as high an affinity for antigen as the OT1 cells. The OT1 TCR is downregulated four- to sixfold more than that of the endogenous T cells upon activation, based on CD3 staining profiles (data not shown). When the tetramer fluorescence is normalized to levels of CD3, the data suggest that the OT1 T cells have significantly higher affinity (5–10-fold) for antigen than the majority of the primary population of responding T cells (data not shown).

It may be that it is this very high affinity for antigen that allows OT1 cells to compete so effectively with endogenous T cells responding to the same peptide. It has previously been shown that repeated immunization reduces the oligoclonality of the responding T cells 31. Moreover, the surviving cells in such immunizations have a higher affinity for antigen than cells in primary infections/immunizations 13 14 15. Perhaps these two types of experiments are manifestations of the same phenomenon, the ability of high affinity T cells to outgrow other cells during repeated challenges with antigen. High affinity for antigen may allow a given T cell to gain and maintain an interaction with antigen-bearing APCs to the exclusion of other lower affinity T cells. Inhibition of the lower affinity T cells of the same specificity may also occur because of physical removal and internalization of the MHC–peptide complex from the surface of a cognate APC by the higher affinity T cells, as recent data have suggested 32.

However, at least some of the inhibition of lower affinity T cells is due simply to the fact that a given APC has a limited surface area with which to interact with T cells and the high affinity T cells preferentially occupy that space. The experiments demonstrating that the high affinity OT1 cells can inhibit responses to other antigens presented by the same APC are in support of this (Fig. 5 and Fig. 7). It is interesting to note that we observed little inhibition of the response against the ova8 epitope when the SIYRYYGL epitope was on the same DC in the absence of the OT1 cells (Fig. 7A and Fig. B, second row). This is consistent with the prediction that while the high affinity OT1 cells compete with both epitopes effectively, the low affinity endogenous cells are inefficient at competing with T cells of other specificities. Further experiments are being done to determine whether cells with decreasing affinity relative to OT1 T cells have a correspondingly decreasing ability to compete for access to antigen-bearing APCs in normal primary and secondary responses.

In light of this notion, it is tempting to consider whether suppressor/regulatory T cells act by competing for access to antigen-bearing APCs. Regulatory T cells subdue the activation of other T cells, and much of this inhibitory activity has been attributed to the effect of Th1- and Th2-related cytokines on the proliferation of the opposite type response 33 34 35. Our data suggest that regulatory T cells may compete against other T cells for access to APCs, either for antigen or cytokine binding. To determine whether this is truly a mechanism of regulatory T cell–mediated inhibition, experiments must be done in which tetramer-staining regulatory T cells are generated in vivo and then assessed for their ability to compete with normal T cells in response to antigen.

Finally, our data suggest that T cell competition is likely to play a role in modifying T cell responses in vaccination strategies. Our demonstration of OT1-mediated inhibition of the minor ovalbumin epitope response demonstrates that competition can occur between T cells of different specificities and that this competition probably shapes the affinity and magnitude of the responding T cell population to each antigen. For example, data in this report show that DC immunization with one or even two epitopes results in a broader range of T cell affinities than does VV-ova immunization (compare level of fluorescence of the tetramer-positive population in Fig. 2 and Fig. 6, Fig. 7, and Fig. 9). Immunization with VV-ova activates potentially competing VV-specific T cells, whereas immunization with DCs does not. Some of this effect may be due to differences in antigen levels between the two procedures. However, a portion of this phenomenon is likely due to the fact that the peptide-pulsed DCs present a small number of epitopes and therefore the ova8-specific population of T cells is subjected to competition only from a limited number of cells with limited specificities. Given this, we speculate that competition between T cells could eventually be exploited to encourage the growth of higher affinity T cells while limiting the growth of lower affinity cells.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Terry Potter for providing the OT1 transgenic mice, Dr. Hyam Levitsky for providing the GM-CSF–producing cell line, Fran Crawford and Kristen Kerber for technical assistance, and Jeremy Bender for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by a Postdoctoral Fellowship Grant from the Cancer Research Institute (to R.M. Kedl) and by grants AI17134, AI18785, and AI22295 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: β2M, β2-microglobulin; B6, C57BL/6J; B6.PL, B6.PL-Thy1a/Cy; DC, dendritic cell; GFP, green fluorescent protein; NP, nucleoprotein; SA-PE, PE-labeled streptavidin; VV, vaccinia virus.

References

- Michaelis L. Untersuchungen uber Eiweissprazipitine. Dtsch. Med. Wschr. 1902;28:733. [Google Scholar]

- Michaelis L. Weitere Untersuchungen uber Eiweissprazipitine. Dtsch. Med. Wschr. 1904;30:1240. [Google Scholar]

- Liacopoulos P., Ben-Efraim S. Antigenic competition. Prog. Allergy. 1975;18:97–204. doi: 10.1159/000395257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchison N.A. Specialization, tolerance, memory, competition, latency, and strife among T cells. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1992;10:1–12. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajewsky K. Clonal selection and learning in the antibody system. Nature. 1996;381:751–758. doi: 10.1038/381751a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyster J.G. Signaling thresholds and interclonal competition in preimmune B-cell selection. Immunol. Rev. 1997;156:87–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00961.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Anton L.C., Bennink J.R., Yewdell J.W. Dissecting the multifactorial causes of immunodominance in class I-restricted T cell responses to viruses. Immunity. 2000;12:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild P.J., Wraith D.C. Lowering the tonemechanisms of immunodominance among epitopes with low affinity for MHC. Immunol. Today. 1996;17:80–85. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)80584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y., Yewdell J.W., Eisenlohr L.C., Bennink J.R. MHC affinity, peptide liberation, T cell repertoire, and immunodominance all contribute to the paucity of MHC class I-restricted peptides recognized by antiviral CTL. J. Immunol. 1997;158:1507–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert E.Z., Grufman P., Sandberg J.K., Tegnesjo A., Karre K. Immunodominance in the CTL response against minor histocompatibility antigensinterference between responding T cells, rather than with presentation of epitopes. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4499–4505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grufman P., Wolpert E.Z., Sandberg J.K., Karre K. T cell competition for the antigen-presenting cell as a model for immunodominance in the cytotoxic T lymphocyte response against minor histocompatibility antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 1999;29:2197–2204. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199907)29:07<2197::AID-IMMU2197>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Khilko S., Fecondo J., Margulies D.H., McCluskey J. Determinant selection of major histocompatibility complex class I–restricted antigenic peptides is explained by class I–peptide affinity and is strongly influenced by nondominant anchor residues. J. Exp. Med. 1994;180:1471–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch D.H., Pamer E.G. T cell affinity maturation by selective expansion during infection. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:701–710. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage P.A., Boniface J.J., Davis M.M. A kinetic basis for T cell receptor repertoire selection during an immune response. Immunity. 1999;10:485–492. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees W., Bender J., Teague T.K., Kedl R.M., Crawford F., Marrack P., Kappler J. An inverse relationship between T cell receptor affinity and antigen dose during CD4+ T cell responses in vivo and in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9781–9786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storb U. Progress in understanding the mechanism and consequences of somatic hypermutation. Immunol. Rev. 1998;162:5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogquist K.A., Jameson S.C., Heath W.R., Howard J.L., Bevan M.J., Carbone F.R. T cell receptor antagonist peptides induce positive selection. Cell. 1994;76:17–27. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J.M., Sterry S.J., Cose S., Turner S.J., Fecondo J., Rodda S., Fink P.J., Carbone F.R. Identification of conserved T cell receptor CDR3 residues contacting known exposed peptide side chains from a major histocompatibility complex class I-bound determinant. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:3318–3326. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J., Crawford F., Fremont D., Marrack P., Kappler J. Soluble class I MHC with β2-microglobulin covalently linked peptidesspecific binding to a T cell hybridoma. J. Immunol. 1999;162:2671–2676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udaka K., Wiesmuller K.H., Kienle S., Jung G., Walden P. Self-MHC-restricted peptides recognized by an alloreactive T lymphocyte clone. J. Immunol. 1996;157:670–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T., Kappler J., Marrack P. Bystander virus infection prolongs activated T cell survival. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4527–4535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Restifo N.P., Bacik I., Irvine K.R., Yewdell J.W., McCabe B.J., Anderson R.W., Eisenlohr L.C., Rosenberg S.A., Bennink J.R. Antigen processing in vivo and the elicitation of primary CTL responses. J. Immunol. 1995;154:4414–4422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky H.I., Lazenby A., Hayashi R.J., Pardoll D.M. In vivo priming of two distinct antitumor effector populationsthe role of MHC class I expression. J. Exp. Med. 1994;179:1215–1224. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porgador A., Yewdell J.W., Deng Y., Bennink J.R., Germain R.N. Localization, quantitation, and in situ detection of specific peptide-MHC class I complexes using a monoclonal antibody. Immunity. 1997;6:715–726. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80447-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingulli E., Mondino A., Khoruts A., Jenkins M.K. In vivo detection of dendritic cell antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:2133–2141. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford F., Kozono H., White J., Marrack P., Kappler J. Detection of antigen-specific T cells with multivalent soluble class II MHC covalent peptide complexes. Immunity. 1998;8:675–682. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80572-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson B.D., Ahmed R. T cell memory. Long-term persistence of virus-specific cytotoxic T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169:1993–2005. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.6.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennink J.R., Doherty P.C. The response to H-2-different virus-infected cells is mediated by long-lived T lymphocytes and is diminished by prior virus priming in a syngeneic environment. Cell. Immunol. 1981;61:220–224. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(81)90368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S.M., Davies G.M., Lin C.M., Zal T., Nasholds W., Jameson S.C., Hogquist K.A., Gascoigne N.R., Travers P.J. Qualitative and quantitative differences in T cell receptor binding of agonist and antagonist ligands. Immunity. 1999;10:227–237. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alam S.M., Travers P.J., Wung J.L., Nasholds W., Redpath S., Jameson S.C., Gascoigne N.R.J. T-cell-receptor affinity and thymocyte positive selection. Nature. 1996;381:616–620. doi: 10.1038/381616a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHeyzer-Williams M.G., Davis M.M. Antigen-specific development of primary and memory T cells in vivo. Science. 1995;268:106–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7535476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J.F., Yang Y., Sepulveda H., Shi W., Hwang I., Peterson P.A., Jackson M.R., Sprent J., Cai Z. TCR-mediated internalization of peptide-MHC complexes acquired by T cells. Science. 1999;286:952–954. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara R.M., Jr. Antigen-specific suppressor factormissing pieces in the puzzle. Immunol. Res. 1995;14:252–262. doi: 10.1007/BF02935623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom B.R., Salgame P., Diamond B. Revisiting and revising suppressor T cells. Immunol. Today. 1992;13:131–136. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90110-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold S., Waldmann H. Infectious tolerance. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 1998;10:518–524. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(98)80217-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]