pH-dependent Perforation of Macrophage Phagosomes by Listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes (original) (raw)

Abstract

The pore-forming toxin listeriolysin O (LLO) is a major virulence factor implicated in escape of Listeria monocytogenes from phagocytic vacuoles. Here we describe the pH-dependence of vacuolar perforation by LLO, using the membrane-impermeant fluorophore 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS) to monitor the pH and integrity of vacuoles in mouse bone marrow–derived macrophages. Perforation was observed when acidic vacuoles containing wild-type L. monocytogenes displayed sudden increases in pH and release of HPTS into the cytosol. These changes were not seen with LLO-deficient mutants. Perforation occurred at acidic vacuolar pH (4.9–6.7) and was reduced in frequency or prevented completely when macrophages were treated with the lysosomotropic agents ammonium chloride or bafilomycin A1. We conclude that acidic pH facilitates LLO activity in vivo.

After entry into cells by phagocytosis, Listeria monocytogenes lyses its vacuole and escapes into the cytosol (1–3), a process that is important for its growth and cell-to-cell spread within a host (1, 4–6). A critical factor implicated in the escape of L. monocytogenes from vacuoles is listeriolysin O (LLO), a sulfhydryl-activated pore-forming toxin secreted by the bacterium (1, 7, 8). Mutants lacking LLO show decreased virulence in mice (9–14), and, in certain types of cultured cells, LLO-deficient mutants remain in vacuoles and do not proliferate (7, 9, 10). Furthermore, Bacillus subtilis strains expressing LLO are able to enter the cytosol of J774 cells, indicating that LLO is sufficient for this process (8).

The action of LLO may be triggered by vacuolar acidification (15, 16). Phagosomes of macrophages containing L. monocytogenes acidify (17), and LLO is more active at an acidic pH in vitro (15). Here we describe the relationship between pH and LLO activity inside _L. monocytogenes–_containing vacuoles. Including the pH-sensitive, membrane-impermeant dye 8-hydroxypyrene-1,3,6-trisulfonic acid (HPTS; reference 18) during macrophage infections permitted labeling of the lumen of endocytic vesicles and measurement of their pH and the integrity of their membranes. This method allowed us to visualize perforation of _L. monocytogenes_–containing vacuoles and indicated a role for acidic vacuolar pH in the activity of LLO in vivo.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and Cells.

All reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) or Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Mouse bone marrow–derived macrophages were obtained from the femurs of female C3H/HeJ mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) and cultured in vitro as described (19). Strains of L. monocytogenes were kindly provided by Dr. Daniel Portnoy (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA) and were grown to stationary phase in Luria-Bertani broth. Just before use, bacteria were washed three times in Ringer's buffer (RB; 155 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 2 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Hepes, 10 mM glucose, pH 7.2). Fresh bacteria were prepared every 2 h.

Macrophage Infections.

Macrophages were kept on a temperature controlled stage set to 37°C, and coverslips containing 1.5–2.0 × 105 cells were incubated with 1 ml 5 mM HPTS in RB and 5–10 μl of a washed L. monocytogenes culture (∼10 CFU/cell). The macrophages were incubated for up to 10 min, during which time an _L. monocytogenes_–infected cell was located. The coverslip was then quickly washed six to seven times with RB, and pH recordings were begun immediately (time 0). Washes with RB were repeated as necessary to reduce background fluorescence.

To inhibit vacuole acidification, 10 mM NH4Cl was included in the first RB wash and all subsequent solutions. Alternatively, 0.5 μM bafilomycin A1 was added to the cells 30 min before infection and throughout the experiment.

Microscopy.

Fluorescent images were collected on an IM-35 inverted microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) equipped for epifluorescence using an ×100 lens, numerical aperture 1.32. The fluorescence excitation system included a 50 W mercury arc lamp and filter changer (Stephen Baer, Photome, Cambridge, MA), which provided alternating 405 and 440 nm excitation wavelengths (exc.); emission was measured at 520 nm. Neutral density filters were sometimes added to reduce photodamage. Images were collected through a video camera, intensified through a multichannel plate intensifier (Video Scope Int. Ltd., Washington, DC). During recording, three images were taken every 15 sec: a 405 nm image, a 440 nm image, and a phase-contrast image. Digital images were assembled into video sequences.

Image Analysis.

Images were analyzed with a Metamorph image analysis system (Universal Imaging Corp., West Chester, PA). Two excitation wavelengths (440 and 405 nm) were used to calculate a ratio value to correct for differences in local dye concentration, optical pathlength, illumination intensity, and photobleaching of samples (20). 440:405 nm ratios were calculated by thresholding the 405 nm image to restrict measurement to the vacuoles of interest. The intensities for identical masked areas were obtained from each of the two fluorescent images and divided to obtain a ratio value. These values were calibrated using HPTS-labeled macrophages incubated with 10 μM nigericin in isotonic potassium buffers of known pH (130 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 15 mM Hepes, 15 mM MES, 0.02% sodium azide). A standard curve was generated by collecting 405 and 440 nm images of fluorescent vacuoles equilibrated at each pH (5.0, 5.5, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, and 7.5).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Vacuolar Perforation by Wild-type L. monocytogenes.

L. monocytogenes were internalized into spacious phagosomes by a process resembling macropinocytosis. This was different from the reported mechanism of L. monocytogenes entry into epithelial cells (21), but similar to the way Salmonella typhimurium enter macrophages (22). Immediately after phagocytosis, individual bacteria could be seen by phase-contrast microscopy as phase-dense rods moving freely inside phase-bright phagosomes; these phagosomes also contained HPTS which was included during the infection (see Fig. 1 a, vesicle 2; Fig. 2 a, vesicle 1; and Fig. 3 a, vesicle 3). No tight-fitting phagosomes were observed, although older phagosomes became smaller and restricted the movement of bacteria.

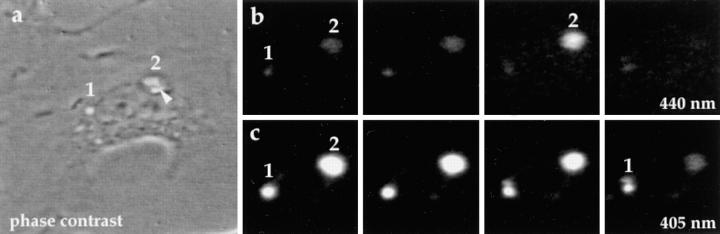

Figure 1.

HPTS fluorescence indicates phagosomal pH and membrane integrity. The macrophage shown by phase contrast microscopy (a) contained two prominent phase-bright vesicles. Vesicle 1 was a macropinosome and vesicle 2 was a spacious phagosome containing three bacteria, visible as phase-dense rods. The fluorescence of HPTS contained in these vesicles is shown for exc. 440 nm (b) and 405 nm (c). The four frames in each series show images taken at 30-s intervals, with the left-most image corresponding to the phase contrast image. At low pH, the fluorescence of HPTS is greater at exc. 405 nm than at 440 nm; conversely, at neutral pH, fluorescence is greater at exc. 440 nm than at 405 nm. Hence, both vesicles appeared acidic in the early time points. Vesicle 1 remained acidic through the series, but vesicle 2 showed an abrupt increase in pH (b and c, third frame), followed by loss of dye (b and c, fourth frame).

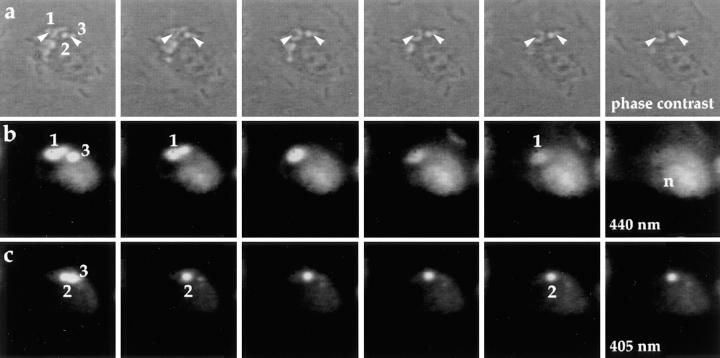

Figure 2.

HPTS from perforated phagosomes diffuses into the cytoplasm and nucleus. The time series shows phase contrast micrographs (a), the corresponding HPTS fluorescence excited at 440 nm (b), and 405 nm (c). Frames in each row were separated by 45-s intervals. Phase-bright phagosomes (a–c, vesicles 1 and 3) and macropinosomes (a–c, vesicle 2) contained HPTS. Initially, vesicle 1 showed bright fluorescence at exc. 440 nm, but very little fluorescence at exc. 405 nm; thus, it was relatively high pH. Its exc. 440 nm fluorescence decreased as dye entered the cytoplasm. Vesicle 2 was fluorescent at exc. 405 nm, but not detectable at 440 nm, indicating an acidic compartmental pH. It remained intact and at low pH through the time series. Vesicle 3 was initially fluorescent at both excitation wavelengths, but lost all fluorescence in the interval between the first and second frames. Accumulation of dye in the cytoplasm and nucleus (n) was indicated by the increased fluorescence at exc. 440 nm distributed diffusely throughout the cell.

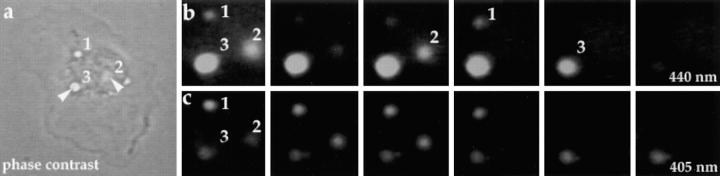

Figure 3.

LLO perforates phagosomes and macropinosomes as they acidify. Three phase-bright vesicles in a macrophage (a) were labeled with HPTS. Fluorescence images at 90-s intervals are shown as a time series in b (440 nm) and c (405 nm). Vesicle 1 was a macropinosome that acidified through the first three frames, then abruptly increased its pH (b and c, frame 4) before losing the dye (b and c, frame 5). Vesicle 2 contained L. monocytogenes; it was initially at a relatively high pH (b and c, frame 1). It then acidified (b and c, frame 2), became abruptly alkaline again (b and c, frame 3), and lost its dye (b and c, frame 4). Vesicle 3, another phagosome, was initially at high pH and remained so until it lost most of its dye.

The pH of _L. monocytogenes_–containing vacuoles and of phase-bright, fluorescent vacuoles that did not contain bacteria was monitored by collecting phase contrast and fluorescence images at regular intervals (Fig. 1). Fluorescent images of HPTS in vacuoles were taken at exc. 405 and 440 nm. The ratio of fluorescence from these two recordings indicated the pH of the probe environment (18): bright fluorescence at exc. 440 nm and dim fluorescence at exc. 405 nm indicated higher pH (>7.2), whereas bright fluorescence at exc. 405 nm and dim fluorescence at 440 nm indicated low pH (<5.0).

Phagosomes began to acidify soon after phagocytosis, with larger ones acidifying more slowly. A typical infection with wild-type L. monocytogenes (Fig. 1), showed one or more macropinosomes (Fig. 1, a–c, vesicle 1) and phagosomes (Fig. 1, a–c, vesicle 2) labeled with HPTS. Whereas the macropinosome remained acidic throughout the period of observation, acidified phagosomes often showed a sudden increase of fluorescence at exc. 440 nm, reflecting an increase in pH (Fig. 1, b and c, frame 3, vesicle 2). Sometimes a slow decrease in pH was followed by an abrupt alkalinization of the phagosome (see Fig. 3, a–c, vesicle 2). The increases in pH were often quickly followed by loss of the fluorescence from the vacuole (Fig. 2, a–c, vesicle 1; Fig. 3, a–c, vesicles 1 and 2). Concomitant increases in the 440 nm fluorescence intensity in the nucleus and cytoplasm of the same cell were usually seen (Fig. 2). Inasmuch as L. monocytogenes escapes from the phagocytic vacuoles of macrophages in an LLO-dependent process (8–11, 13), and as HPTS has been shown to be released from LLO-destabilized compartments (23), the sudden pH increases likely resulted from equilibration of the pH across the vacuolar membrane after perforation by LLO. Further destabilization of the membrane released HPTS into the cytoplasm.

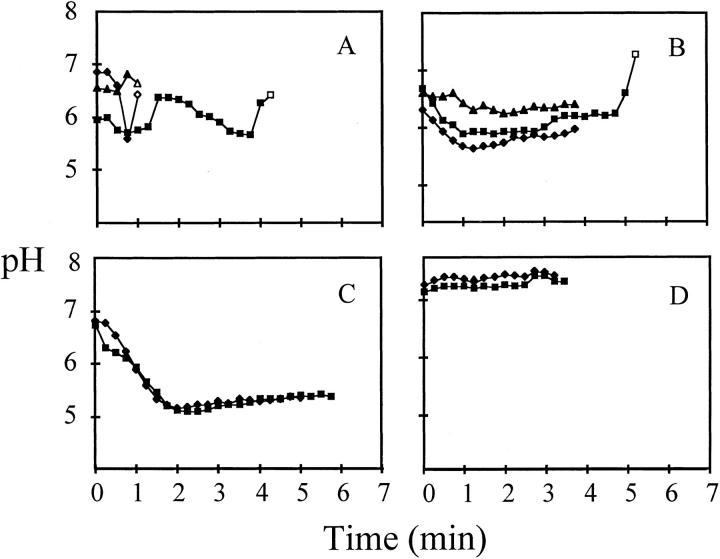

To calculate the pH of individual phagosomes, digital images were recorded at exc. 440 and 405 nm, and the intensity values from corresonding areas in the two images were divided to obtain ratio values (I440:I405). The ratios were calibrated using pH-clamped cells. Fig. 4, A and B, shows representative changes of pH for vacuoles in cells infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes. The pH of the bacterium-containing vacuoles decreased and then abruptly increased by 0.2–1.6 pH U. Increases in pH were observed in 24 out of 52 vacuoles containing L. monocytogenes (Table 1). The increases were rapid and usually accompanied by release of dye into the cytoplasm. Release of HPTS did not always follow the rise in pH. In fact, sometimes vacuoles reacidified (Fig. 4 A). This reacidification was often followed by another sudden increase in pH and more complete release of the HPTS into the cytosol.

Figure 4.

pH analysis of _L. monocytogenes_–containing vacuoles. Quantitative fluorescence microscopy was used to determine the fluorescence intensities of vacuoles containing HPTS after infection with L. monocytogenes. A standard curve of pH to 440:405 nm intensity ratios was used to calibrate the pH of the fluorescence intensities. These graphs are representative time courses from several experiments. Open symbols represent a sudden loss of fluorescence from the vacuole and, therefore, the end of the experiment. Traces that end in closed symbols are those that did not show a sudden loss of fluorescence. These experiments were continued until the fluorescence signal was lost through quenching and recycling of the HPTS. (A) Phagosomes containing wild-type L. monocytogenes. Vacuoles showed sudden increases in pH followed by a decrease in the fluorescence signal as the HPTS was released to the cytoplasm. In some cases, phagosomes reacidified and showed a secondary pH increase (squares). (B) Control vacuoles in cells infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes. These vacuoles acidified and occasionally showed evidence of perforation (squares). (C) Cells were infected with DP-L2161 (diamond, phagosome; square, control vacuole). This L. monocytogenes mutant lacks LLO because of an hly deletion. (D) Cells were infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes in the presence of 0.5 μM bafilomycin A1.

Table 1.

Vacuolar Perforation Requires LLO and Is Prevented by Raising pH

| WT* | DP-L2161 | DP-L2864 | WT + NH4 Cl | WT + bafilomycin A1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24/52 | 0/19 | 0/10 | 3/16 | 0/16 |

Sudden increases in pH were sometimes seen in macropinosomes of cells infected with the wild-type bacterium (Figs. 3 and 4 B; 7 out of 36 vacuoles). These increases occurred in a pH range similar to that of phagosomes and probably resulted from soluble LLO pinocytosed from the medium.

A Requirement for LLO.

Two mutants deficient in LLO failed to show any sudden increases in vacuolar pH. The first mutant, DP-L2864 (hly-, plca-, plcb-, mpl-) lacks several virulence factors implicated in vacuolar perforation, including LLO, a phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, a phosphatidylcholine-preferring phospholipase C, and a metalloprotease (24–27). The second mutant, DP-L2161 (28), has a single, in-frame deletion of hly, the structural gene for LLO. Vacuoles containing either of these acidified and maintained a low pH. Sudden increases in pH and release of dye into the cytoplasm were never observed with either mutant (Table 1), indicating that LLO was required for perforation.

The Perforation Activity of LLO is Facilitated by Acidic pH.

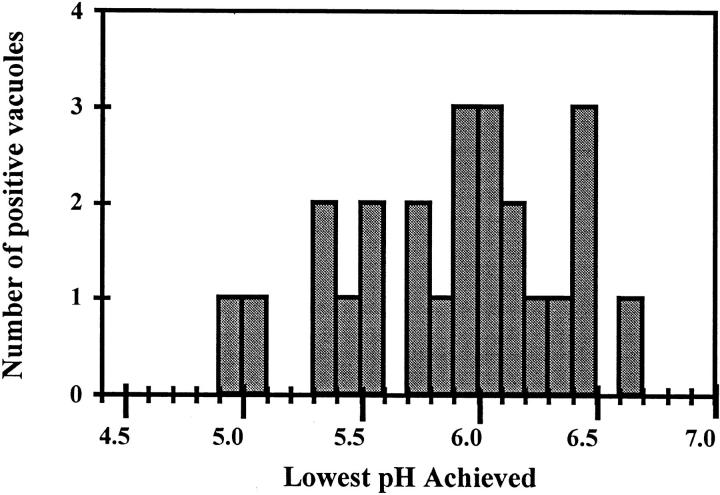

To determine the optimal pH for LLO activity in vivo, we measured the lowest pH achieved by each vacuole before perforation. Perforation occurred over a range of acidic pH values from 4.9 to 6.7, with a mean near 6.0 (mean = pH 5.94, SD = 0.45; Fig. 5), consistent with earlier suggestions that vacuole acidification creates optimal conditions for LLO activity in vivo (15–17).

Figure 5.

Wild-type L. monocytogenes perforates vacuoles at a mean pH of 5.94. To determine whether there was a pH requirement for vacuole perforation, the lowest pH achieved by a vacuole just before the primary pH increase was recorded. The number of vacuoles that showed perforation at each pH is graphed here. The frequency of perforation increases at approximately pH 6.0.

There are conflicting reports as to whether inhibitors of vacuole acidification prevent L. monocytogenes from moving to the cytosol (5, 29, 30). To determine whether low pH was required for LLO to induce vacuolar perforation, macrophages were infected with wild-type L. monocytogenes in the presence of NH4Cl, a weak base that raises the pH of acidic vesicles (31), or bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of vacuolar proton ATPases (32). In the presence of bafilomycin A1, phagosomes maintained a steady, alkaline pH (Fig. 4 C). Vacuolar perforation, as monitored by leakage of the HPTS to the cytoplasm, was completely prevented by bafilomycin A1 (0 out of 16; Table 1) and was less frequent in NH4Cl (3 out of 16). Consistent with the results of Okhuma and Poole (33), 10 mM NH4Cl elevated pH but did not completely prevent acidification of macrophage vacuoles. 65% of _L. monocytogenes–_containing vacuoles in NH4Cl-treated cells were pH 7 or less, as opposed to 33% of vacuoles in bafilomycin A1–treated cells. The vacuoles that showed perforation in the presence of NH4Cl were within the range of pH at which perforation occurred without this compound. These results show that the level of acidification corresponded with the amount of LLO activity observed (46% for buffer, 19% for NH4Cl, and 0% for bafilomycin A1; Table 1). This is consistent with the fact that weak bases cause a slight decrease in intracellular growth of L. monocytogenes (5, 29), as the number of bacteria that could escape to the cytosol was reduced in the presence of NH4Cl.

Although it is established that L. monocytogenes escapes its vacuole, the mechanism of this process remains ill-defined. Evidence presented here shows that one of the earliest detectable steps in vacuole lysis is perforation of the membrane, indicated by an abrupt increase in vacuolar pH and by leakage of its contents. These changes required LLO and acidic pH. We conclude that acidic pH facilitates LLO activity in vivo through an undefined mechanism.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Daniel Portnoy for providing the strains used in this paper and for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr. Wayne Lencer for providing the bafilomycin A1 used in the initial experiments, David Garber for critical reading of the manuscript, and members of the Swanson lab for helpful suggestions.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI-35950 (to J.A. Swanson) and AI-22021 (to R.J. Collier).

REFERENCES

- 1.Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. . J Cell Biol. 1989;109:1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Portnoy DA, Jones S. The cell biology of Listeria monocytogenes(escape from a vacuole) Ann NY Acad Sci. 1994;730:15–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armstrong BA, Sword CP. Electron microscopy of Listeria monocytogenes–infected mouse spleen. J Bacteriol. 1966;91:1346–1355. doi: 10.1128/jb.91.3.1346-1355.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camilli A, Tilney LG, Portnoy DA. Dual roles of plcA in Listeria monocytogenespathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01211.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Portnoy, D.A., A.N. Sun, and J. Bielecki. 1992. Escape from the phagosome and cell-to-cell spread of Listeria monocytogenes. In Microbial Adhesion and Invasion. M. Hook and L. Switalksi, editors. Springer Verlag, New York. 85–94.

- 6.Havell EA. Synthesis and secretion of interferon by murine fibroblasts in response to intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. . Infect Immun. 1986;54:787–792. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.787-792.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaillard J-L, Berche P, Mounier J, Richard S, Sansonetti P. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenesin the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2822-2829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bielecki J, Youngman P, Connelly P, Portnoy DA. Bacillus subtilis expressing a haemolysin gene from Listeria monocytogenescan grow in mammalian cells. Nature (Lond) 1990;345:175–176. doi: 10.1038/345175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Portnoy DA, Jacks PS, Hinrichs DJ. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. . J Exp Med. 1988;167:1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn M, Kathariou S, Goebel W. Hemolysin supports survival but not entry of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. . Infect Immun. 1988;56:79–82. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.1.79-82.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michel E, Reich KA, Favier R, Berche P, Cossart P. Attenuated mutants of the intracellular bacterium Listeria monocytogenesobtained by single amino acid substitutions in listeriolysin O. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:2167–2178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kathariou S, Metz P, Hof H, Goebel W. Tn916-induced mutations in the hemolysin determinant affecting virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. . J Bacteriol. 1987;169:1291–1297. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1291-1297.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaillard JL, Berche P, Sansonetti P. Transposon mutagenesis as a tool to study the role of hemolysin in the virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. . Infect Immun. 1986;52:50–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.1.50-55.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cossart P, Vicente MF, Mengaud J, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz JC, Berche P. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3629-3636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geoffroy C, Gaillard J-L, Alouf JE, Berche P. Purification, characterization, and toxicity of the sulfhydryl-activated hemolysin listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes. . Infect Immun. 1987;55:1641–1646. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1641-1646.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kingdon GC, Sword CP. Effects of Listeria monocytogeneshemolysin on phagocytic cells and lysosomes. Infect Immun. 1970;1:356–362. doi: 10.1128/iai.1.4.356-362.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Chastellier C, Berche P. Fate of Listeria monocytogenesin murine macrophages: evidence for simultaneous killing and survival of intracellular bacteria. Infect Immun. 1994;62:543–553. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.543-553.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giuliano KA, Gillies RJ. Determination of intracellular pH of BALB/c-3T3 cells using the fluorescence of pyranine. Anal Biochem. 1987;167:362–371. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanson JA. Phorbol esters stimulate macropinocytosis and solute flow through macrophages. J Cell Sci. 1989;94:135–142. doi: 10.1242/jcs.94.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bright GR, Fisher GW, Rogowska J, Taylor DL. Fluorescence ratio imaging microscopy: temporal and spatial measurements of cytoplasmic pH. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:1019–1033. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.4.1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mengaud J, Ohayon H, Gounon P, Mege RM, Cossart P. E-cadherin is the receptor for internalin, a surface protein required for entry of L. monocytogenesinto epithelial cells. Cell. 1996;84:923–932. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alpuche-Aranda CM, Racoosin EL, Swanson JA, Miller SI. Salmonellastimulate macrophage macropinocytosis and persist within spacious phagosomes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K-D, Oh Y-K, Portnoy DA, Swanson JA. Delivery of macromolecules into cytosol using liposomes containing hemolysin from Listeria monocytogenes. . J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7249–7252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vazquez-Boland J-A, Kocks C, Dramsi S, Ohayon H, Geoffroy C, Mengaud J, Cossart P. Nucleotide sequence of the lecithinase operon of Listeria monocytogenesand possible role of lecithinase in cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1992;60:219–230. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.219-230.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith GA, Marquis H, Jones S, Johnston NC, Portnoy DA, Goldfine H. The two distinct phospholipases C of Listeria monocytogeneshave overlapping roles in escape from a vacuole and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4231–4237. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4231-4237.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marquis H, Doshi V, Portnoy DA. The broad-range phospholipase C and a metalloprotease mediate listeriolysin O–independent escape of Listeria monocytogenesfrom a primary vacuole in human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4531–4534. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4531-4534.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Camilli A, Goldfine H, Portnoy DA. Listeria monocytogenesmutants lacking phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C are avirulent. J Exp Med. 1991;173:751–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones S, Portnoy DA. Characterization of Listeria monocyogenespathogenesis in a strain expressing perfringolysin O in place of listeriolysin O. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5608–5613. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5608-5613.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Portnoy DA, Tweten RK, Kehoe M, Bielecki J. Capacity of listeriolysin O, streptolysin O, and perfringolysin O to mediate growth of Bacillus subtiliswithin mammalian cells. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2710–2717. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2710-2717.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Conte MP, Petrone G, Longhi C, Valenti P, Morelli R, Superti F, Seganti L. The effects of inhibitors of vacuolar acidification on the release of Listeria monocytogenesfrom phagosomes of Caco-2 cells. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:418–424. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-6-418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poole B, Okhuma S. Effect of weak bases on the intralysosomal pH in mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Cell Biol. 1981;90:665–669. doi: 10.1083/jcb.90.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins: a class of inhibitors of membrane ATPases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okhuma S, Poole B. Fluorescence probe measurement of the intralysosomal pH in living cells and the perturbation of pH by various agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3327–3331. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]