Elevated substitution rates estimated from ancient DNA sequences (original) (raw)

Abstract

Ancient DNA sequences are able to offer valuable insights into molecular evolutionary processes, which are not directly accessible via modern DNA. They are particularly suitable for the estimation of substitution rates because their ages provide calibrating information in phylogenetic analyses, circumventing the difficult task of choosing independent calibration points. The substitution rates obtained from such datasets have typically been high, falling between the rates estimated from pedigrees and species phylogenies. Many of these estimates have been made using a Bayesian phylogenetic method that explicitly accommodates heterochronous data. Stimulated by recent criticism of this method, we present a comprehensive simulation study that validates its performance. For datasets of moderate size, it produces accurate estimates of rates, while appearing robust to assumptions about demographic history. We then analyse a large collection of 749 ancient and 727 modern DNA sequences from 19 species of animals, plants and bacteria. Our new estimates confirm that the substitution rates estimated from ancient DNA sequences are elevated above long-term phylogenetic levels.

Keywords: demographic model, model selection, Bayes factor, heterochronous sequences, time dependency

1. Introduction

Ancient DNA (aDNA) sequences have been proliferating rapidly over the past two decades, with datasets now ranging from population-scale genetic profiles (Lambert et al. 2002; Shapiro et al. 2004) to palaeogenomic libraries (e.g. Noonan et al. 2005). In many cases, the ages of aDNA sequences are known from radiocarbon dating or stratigraphic context, allowing detailed investigations of molecular evolutionary processes through time (Drummond et al. 2002). These known ages can be used as calibrations for estimating substitution rates, divergence times and various demographic parameters in the absence of any other calibration points (Rambaut 2000; Drummond et al. 2002).

One of the notable characteristics of aDNA datasets is that they have generally yielded elevated estimates of substitution rates (for a summary, see Ho et al. (2007)). Typically, such estimates have been intermediate between the mutation rates inferred from pedigree studies (e.g. Denver et al. 2000; Howell et al. 2003) and the long-term substitution rates obtained from phylogenetic studies (e.g. Brown et al. 1979). These results suggest that rate estimates depend on the length of the observational period, with higher rates being measured over shorter periods of time (Ho et al. 2005). Hypothesized causes for this pattern include the persistence of slightly deleterious mutations, sequence damage, calibration error or substitutional saturation (Ho et al. 2005, 2007; Woodhams 2006). Although the relative contributions of these factors are difficult to quantify, it is clear that the time dependency of rate estimates represents a considerable problem for molecular studies of recent evolutionary events.

Recently, the ability of Bayesian phylogenetic analysis to infer substitution rates from dated aDNA sequences was questioned (Emerson 2007). This criticism was based on anomalous results obtained from a sequence analysis of four dated Neanderthals and four modern humans, in which Emerson (2007) estimated the substitution rate to be 1.98 substitutions per site Myr−1. A subsequent re-analysis was unable to replicate these findings (Ho et al. 2007). Validation of various aspects of the method has been performed previously (Drummond et al. 2002, 2006), but not in a simulation study using parameter settings that are biologically relevant to aDNA data. Comprehensive testing of the method is desirable due to its pivotal role in many aDNA studies (e.g. Lambert et al. 2002; Shapiro et al. 2004).

In order to assess the accuracy and precision of the substitution rates estimated using Bayesian analysis, we present a study based on datasets generated by simulation under known conditions. The robustness of the estimates to the assumed demographic model is also assessed. We then estimate intraspecific substitution rates from a collection of nearly 1500 sequences obtained from a diverse range of animals, plants and bacteria. Demographic model selection is performed using Bayes factors.

2. Material and methods

(a) Simulations

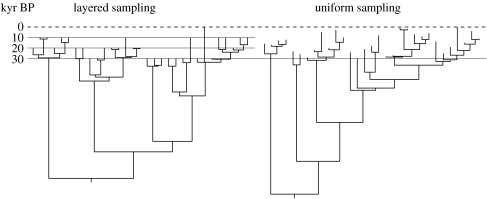

Simulations of sequence evolution were performed on 4000 random coalescent trees with 31 dated tips. For the first 2000 trees, the ages of the tips were 0, 1000, 2000, …, 30 000 years, reflecting a population that has been uniformly sampled over a period of time (e.g. Shapiro et al. 2004). For the second 2000 trees, there was one modern sequence (age 0) and 10 sequences each of ages 10 000, 20 000 and 30 000 years, reflecting samples from a limited number of sites or layers (e.g. Coolen & Overmann 2007). These two sampling regimes are hereafter referred to as ‘uniform’ and ‘layered’, respectively; examples of simulation trees from these two regimes are given in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Examples of two 31-taxon trees used for simulation, obtained under two sampling regimes: layered and uniform. A detailed description of the two sampling regimes is given in the text.

For each of the two sets of 2000 trees, the first 1000 were generated assuming a constant population size of 105 and the second 1000 assuming an exponentially growing population, with a growth rate of 10−5 per year and a final population size of 105. Simulations were performed on all 4000 trees using Seq-Gen v. 1.3.2 (Rambaut & Grassly 1997), using the Jukes–Cantor model of nucleotide substitution with a rate of 5×10−7 substitutions per site yr−1, to produce alignments of length 1000 bp.

Substitution rates and root ages were estimated from these alignments using the Bayesian phylogenetic software Beast v. 1.4.3 (Drummond & Rambaut 2006), with sequence ages used as calibrations. For each alignment, analyses were performed using three demographic models: (i) constant population size, (ii) exponential growth and (iii) the Bayesian skyline plot with five groups (Drummond et al. 2005). Posterior distributions of genealogies and parameters were obtained by Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling, with samples from the posterior drawn every 5000 steps over a total of 5 000 000 steps.

(b) Ancient and modern DNA

Nucleotide sequences were obtained from published sources for 19 species, with the total dataset comprising 749 ancient and 727 modern sequences (table 1; see also electronic supplementary material). Most sequences were from the mitochondrial D-loop. All of the ancient sequences were of known age. Following manual alignment, several population genetic statistics were computed using DnaSP v. 10.4.9 (Rozas et al. 2003) for the modern sequences. First, the number of segregating sites (S) and the average number of pairwise nucleotide differences (k; Tajima 1983) were calculated. High S/k ratios (‘expansion coefficient’; Peck & Congdon 2004) imply an increase in population size over time, while lower ratios should be indicative of a relatively constant long-term population size. We also used a test statistic, _R_2, that draws information from the polymorphism frequency. _R_2 contrasts the number of singletons and the mean number of differences; it approaches low positive values in the case of a recent population growth event (Ramos-Onsins & Rozas 2002). Several other statistics were calculated and are presented in the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1.

Ancient DNA datasets analysed in this study, along with several population genetic statistics.

| species | locus | sequences (ancient/modern)a | length (bp) | oldest sequence (years) | substitution modelb | demographic statisticsc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/k | _R_2 | BF | |||||||

| Adélie penguin | Pygoscelis adeliae | D-loop | 96/380 | 347 | 6424 | GTR+G+I | 12.90 | 0.038* | con |

| Arctic fox | Alopex lagopus | D-loop | 8/41 | 293 | 16 000 | TrN+G | 6.13 | 0.075 | con |

| aurochs | Bos primigenius | D-loop | 41/0 | 360 | 11 930 | HKY+I | — | — | BSP* |

| bison | Bison bison | D-loop | 160/22 | 615 | 60 400 | TIM+G+I | 4.37 | 0.104 | BSP** |

| boar | Sus scrofa | D-loop | 81/7 | 572 | 5400 | HKY+G+I | 2.07 | 0.218 | con |

| bowhead whale | Balaena mysticetus | D-loop | 99/68 | 453 | 51 000 | HKY+G+I | 6.94 | 0.069 | con |

| brown bear | Ursus arctos | D-loop | 37/56 | 193 | 59 000 | TrN+G | — | — | con |

| cave bear | Ursus spelaeus | D-loop | 26/0 | 288 | 80 000 | HKY+I | — | — | con |

| cave hyaena | Crocuta crocuta spelaea | D-loop | 10/0 | 366 | 51 200 | F81 | — | — | BSP |

| cave lion | Panthera leo spelaea | D-loop | 23/0 | 213 | 58 200 | TrN | — | — | con |

| cow | Bos taurus | D-loop | 36/91 | 410 | 8065 | K3Puf+G+I | 13.49 | 0.033* | BSP** |

| horse | Equus caballus | D-loop | 12/33 | 348 | 28 340 | GTR+G+I | 5.53 | 0.080 | exp** |

| moa | Pachyornis mappini | D-loop | 14/0 | 241 | 6227 | TrN+I | — | — | con |

| musk ox | Ovibos moschatus | D-loop | 12/5 | 114 | 40 270 | HKY | — | — | con |

| nene | Branta sandvicensis | tRNA, atp8 | 4/0 | 194 | 3190 | F81 | — | — | con |

| tuco-tuco | Ctenomys sociabilis | cytb | 45/1 | 253 | 10 208 | K3Puf+I | — | — | con |

| woolly mammoth | Mammuthus primigenius | D-loop | 32/0 | 741 | 46 600 | TIM+G+I | — | — | con |

| maize | Zea mays | adh2 | 9/11 | 190 | 4500 | HKY | 3.04 | 0.144 | con |

| Chlorobium | Chlorobium limicola | Genomic 16S | 4/12 | 478 | 206 000 | TVM+I | 2.41 | 0.194 | exp |

Nucleotide substitution models were selected for each dataset by comparison of Akaike's information criterion scores. Substitution rates were estimated from each of the 19 alignments using Beast. For each alignment, analyses were performed using the three different demographic models: (i) constant population size, (ii) exponential growth and (iii) the Bayesian skyline plot with five groups. Samples from the posterior were drawn every 20 000 MCMC steps over a total of 20 000 000 steps. Acceptable mixing and convergence to the stationary distribution were checked by inspection of posterior samples. Demographic model selection was performed by Bayes factors calculated using the harmonic means of sampled marginal likelihoods and support was assessed following Jeffreys (1961).

3. Results

(a) Simulations

The simulation study revealed that estimates of substitution rates made using Bayesian analysis were robust to the assumed demographic model (table 2). Analyses using the exponential growth model and Bayesian skyline plot yielded slightly higher rate estimates than those assuming a constant population size, but mean rate estimates were strikingly consistent across different demographic models. The estimation accuracy, defined here as the percentage of datasets for which the true rate (5×10−7 substitutions per site yr−1) was contained in the 95% highest posterior density (HPD) of the estimated rate, remained at approximately 95% regardless of the demographic model assumed during the analysis.

Table 2.

Bayesian phylogenetic estimates of substitution rates and root ages from data simulated under various conditions, with all values calculated from 1000 independent replicates.

| structure of sequence ages | model used in simulation | model used in analysis | substitution rate estimate | root age estimate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean (substitution per site yr−1) | accuracya (%) | precisionb | accuracya (%) | |||

| uniform | constant size | constant size | 4.95×10−7 | 94.4 | 2.52×10−7 | 94.9 |

| uniform | constant size | exponential growth | 5.03×10−7 | 94.2 | 2.52×10−7 | 94.5 |

| uniform | constant size | Bayesian skyline plot | 5.03×10−7 | 94.0 | 2.51×10−7 | 94.6 |

| uniform | exponential growth | constant size | 5.00×10−7 | 94.3 | 2.44×10−7 | 95.6 |

| uniform | exponential growth | exponential growth | 5.08×10−7 | 94.2 | 2.46×10−7 | 93.5 |

| uniform | exponential growth | Bayesian skyline plot | 5.10×10−7 | 94.0 | 2.47×10−7 | 94.8 |

| layered | constant size | constant size | 4.95×10−7 | 95.0 | 2.65×10−7 | 95.6 |

| layered | constant size | exponential growth | 5.03×10−7 | 95.4 | 2.66×10−7 | 95.1 |

| layered | constant size | Bayesian skyline plot | 5.04×10−7 | 94.8 | 2.66×10−7 | 95.3 |

| layered | exponential growth | constant size | 5.00×10−7 | 94.7 | 2.59×10−7 | 94.6 |

| layered | exponential growth | exponential growth | 5.09×10−7 | 93.8 | 2.61×10−7 | 92.6 |

| layered | exponential growth | Bayesian skyline plot | 5.11×10−7 | 95.4 | 2.63×10−7 | 93.8 |

The precision of the estimates, defined here as the average size of the 95% HPD on the estimated rate, was also remarkably consistent across the different conditions. Results were similar between the uniform and layered sampling regimes, although the rates estimated from the former were slightly less accurate but more precise. This final result differs from that obtained in a similar study of viral sampling regimes (Seo et al. 2002), but this could be the result of differences in simulation conditions and the analytical method. Nevertheless, the performance of the Bayesian method using layered sampling data is reassuring, because layered sampling is more economical and sometimes unavoidable in practice.

(b) DNA data

Two of the nine modern DNA datasets yielded significant values for R 2 (table 1; see also electronic supplementary material), reflecting a departure from the null model of constant population size and presenting evidence of population expansion. There were some disagreements with the demographic priors selected using Bayes factors (table 1), but this could be due to the exclusive use of modern sequences for calculating the population genetic statistics.

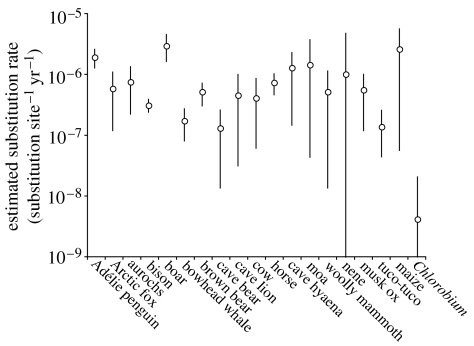

Estimated substitution rates from animal D-loop datasets were generally high (figure 2), with mean estimates ranging from 1.3×10−7 (95% HPD: 1.3×10−8–2.6×10−7) in cave bear to 2.9×10−6 (95% HPD: 1.6×10−6–4.4×10−6) in boar. The rate estimated from Chlorobium was lower than all other rates by two orders of magnitude, suggesting that either the species evolves extremely slowly or the ancient sequences are spurious.

Figure 2.

Rates estimated from a range of aDNA datasets. Bars denote 95% HPD.

4. Discussion

The simulation study validates the Bayesian phylogenetic estimation of substitution rates from heterochronous data using Beast. It also demonstrates that estimates of substitution rates are relatively robust to the assumed demographic model, at least for biologically realistic simulation conditions. It is probable that estimates made from alignments with lower information content will be less robust to the demographic prior, although the extent of this influence requires further investigation using a wider set of simulation parameters.

The analyses of aDNA data have yielded a collection of substitution rate estimates that are higher than those obtained on phylogenetic time scales. In some cases, they confirm previous estimates made using similar methods (e.g. Shapiro et al. 2004).

Our analyses demonstrate that elevated rates estimated from aDNA are not artefacts of the Bayesian estimation method, as recently claimed (Emerson 2007). With developments in sequencing technology and the growing availability of data, such methods will become increasingly important in extracting the molecular evolutionary information contained in ancient sequences.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rob DeSalle for comments on the paper, Andrew Rambaut and Alexei Drummond for their advice, and Ross Barnett for providing unpublished data. S.Y.W.H. was supported by the Leverhulme Trust. S.O.K. was supported by a Conservation Genetics Research Fellowship from the AMNH Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics and the Cullman Program in Molecular Systematics.

Supplementary Material

Data sets and population genetic statistics

Summary and neutrality statistics, model abbreviations, and data sources

References

- Brown W.M, George M, Jr, Wilson A.C. Rapid evolution of animal mitochondrial DNA. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1979;76:1967–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1967. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.4.1967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolen M.J, Overmann J. 217 000-year-old DNA sequences of green sulfur bacteria in Mediterranean sapropels and their implications for the reconstruction of the paleoenvironment. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;9:238–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01134.x. doi:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01134.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denver D.R, Morris K, Lynch M, Vassilieva L.L, Thomas W.K. High direct estimate of the mutation rate in the mitochondrial genome of Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2000;289:2342–2344. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5488.2342. doi:10.1126/science.289.5488.2342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J, Rambaut A. University of Oxford; Oxford, UK: 2006. Beast. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J, Nicholls G.K, Rodrigo A.G, Solomon W. Estimating mutation parameters, population history and genealogy simultaneously from temporally spaced sequence data. Genetics. 2002;161:1307–1320. doi: 10.1093/genetics/161.3.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J, Rambaut A, Shapiro B, Pybus O.G. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi103. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J, Ho S.Y.W, Phillips M.J, Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e88. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson B.C. Alarm bells for the molecular clock? No support for Ho et al.'s model of time-dependent molecular rate estimates. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:337–345. doi: 10.1080/10635150701258795. doi:10.1080/10635150701258795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S.Y.W, Phillips M.J, Cooper A, Drummond A.J. Time dependency of molecular rate estimates and systematic overestimation of recent divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2005;22:1561–1568. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi145. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S.Y.W, Shapiro B, Phillips M, Cooper A, Drummond A.J. Evidence for time dependency of molecular rate estimates. Syst. Biol. 2007;56:515–522. doi: 10.1080/10635150701435401. doi:10.1080/10635150701435401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell N, Smejkal C.B, Mackey D.A, Chinnery P.F, Turnbull D.M, Herrnstadt C. The pedigree rate of sequence divergence in the human mitochondrial genome: there is a difference between phylogenetic and pedigree rates. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2003;72:659–670. doi: 10.1086/368264. doi:10.1086/368264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys H. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1961. The theory of probability. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D.M, Ritchie P.A, Millar C.D, Holland B, Drummond A.J, Baroni C. Rates of evolution in ancient DNA from Adélie penguins. Science. 2002;295:2270–2273. doi: 10.1126/science.1068105. doi:10.1126/science.1068105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noonan J.P, et al. Genomic sequencing of Pleistocene cave bears. Science. 2005;309:597–569. doi: 10.1126/science.1113485. doi:10.1126/science.1113485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck D.R, Congdon D.C. Reconciling historical processes and population structure in the sooty tern Sterna fuscata. J. Avian Biol. 2004;35:327–335. doi:10.1111/j.0908-8857.2004.03303.x [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A. Estimating the rate of molecular evolution: incorporating non-contemporaneous sequences into maximum likelihood phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:395–399. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.395. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A, Grassly N.C. Seq-Gen: an application for the Monte Carlo simulation of DNA sequence evolution along phylogenetic trees. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:235–238. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-Onsins S.E, Rozas J. Statistical properties of new neutrality tests against population growth. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2002;19:2092–2100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozas J, Sanchez-DelBarrio J.C, Messeguer X, Rozas R. DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:2496–2497. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btg359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo T.K, Thorne J.L, Hasegawa M, Kishino H. A viral sampling design for testing the molecular clock and for estimating evolutionary rates and divergence times. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:115–123. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.115. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/18.1.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro B, et al. Rise and fall of the Beringian steppe bison. Science. 2004;306:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1101074. doi:10.1126/science.1101074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics. 1983;105:437–460. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams M. Can deleterious mutations explain the time dependency of molecular rate estimates? Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2271–2273. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl107. doi:10.1093/molbev/msl107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data sets and population genetic statistics

Summary and neutrality statistics, model abbreviations, and data sources