A korarchaeal genome reveals insights into the evolution of the Archaea (original) (raw)

Abstract

The candidate division Korarchaeota comprises a group of uncultivated microorganisms that, by their small subunit rRNA phylogeny, may have diverged early from the major archaeal phyla Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota. Here, we report the initial characterization of a member of the Korarchaeota with the proposed name, “Candidatus Korarchaeum cryptofilum,” which exhibits an ultrathin filamentous morphology. To investigate possible ancestral relationships between deep-branching Korarchaeota and other phyla, we used whole-genome shotgun sequencing to construct a complete composite korarchaeal genome from enriched cells. The genome was assembled into a single contig 1.59 Mb in length with a G + C content of 49%. Of the 1,617 predicted protein-coding genes, 1,382 (85%) could be assigned to a revised set of archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COGs). The predicted gene functions suggest that the organism relies on a simple mode of peptide fermentation for carbon and energy and lacks the ability to synthesize de novo purines, CoA, and several other cofactors. Phylogenetic analyses based on conserved single genes and concatenated protein sequences positioned the korarchaeote as a deep archaeal lineage with an apparent affinity to the Crenarchaeota. However, the predicted gene content revealed that several conserved cellular systems, such as cell division, DNA replication, and tRNA maturation, resemble the counterparts in the Euryarchaeota. In light of the known composition of archaeal genomes, the Korarchaeota might have retained a set of cellular features that represents the ancestral archaeal form.

Keywords: microbial cultivation, genomics, hyperthermophiles, Korarchaeota, phylogeny

Two established phyla, the Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota, divide the archaeal domain based on fundamental differences in translation, transcription and replication (1). Yet hydrothermal environments have yielded small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene sequences that form deep-branching phylogenetic lineages, which potentially lie outside of these major groups. These uncultivated organisms include members of the Korarchaeota (2–4), the Ancient Archaeal Group (5), and the Marine Hydrothermal Vent Group (5, 6). The Nanoarchaeota have also been suggested to hold a basal phylogenetic position (7), but this placement has been debated (8). The Korarchaeota comprise the largest group of deep-branching unclassified archaea and have been detected in several geographically isolated terrestrial and marine thermal environments (2, 4, 5, 9–17).

To gain insights into the Korarchaeota, we revisited the original site where Barns et al. (2) collected korarchaeal environmental SSU rDNA sequences (pJP78 and pJP27) from Obsidian Pool, Yellowstone National Park (YNP), Wyoming. Continuous enrichment cultures were established at 85°C by using a dilute organic medium and sediment samples from Obsidian Pool as an inoculum. The cultivation system supported the stable growth of a mixed community of hyperthermophilic bacteria and archaea including an organism with a SSU rDNA sequence displaying 99% identity to pJP27. The organism was identified as an ultrathin filament between 0.16 and 0.18 μm in diameter and variable in length. Whole-genome shotgun (WGS) sequencing was used to assemble an intact composite genome from purified cells originating from the enrichment culture. The complete genome sequence of “Candidatus (Ca.) Korarchaeum cryptofilum” provides a look into the biology of these deeply branching archaea and their evolutionary relationships with Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota.

Results

Cultivation and in Situ Identification.

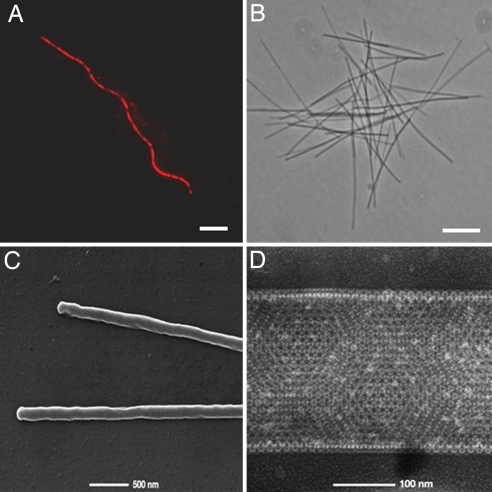

An enrichment culture was inoculated with sediment and hot spring samples taken from Obsidian Pool, YNP. The enrichment was maintained under strictly anaerobic conditions at 85°C, pH 6.5, and continuously fed a dilute organic medium. A stable community of hyperthermophilic archaea and bacteria with a total cell density of ≈1.0 × 108 cells per ml was supported for nearly 4 years. Sequences from SSU rDNA clone libraries derived from the enrichment were closely related to other known isolates or environmental sequences from Obsidian Pool [see supporting information (SI) Text and Fig. S1]. The Korarchaeota were represented by the SSU rDNA clone pOPF_08, which is 99% identical to pJP27 from Obsidian Pool, YNP (2), and pAB5 from Calcite Springs, YNP (9). FISH analysis allowed the positive identification of cells with the pOPF_08 SSU rRNA sequence. Cells hybridizing to Cy3-labeled, _Korarchaeota_-specific probes, KR515R and KR565R, were ultrathin filaments <0.2 μm in diameter with an average length of 15 μm, although cells were observed with lengths up to 100 μm (Fig. 1A, Fig. S2, and SI Text).

Fig. 1.

Microscopy of Ca. K. cryptofilum. (A) FISH analysis with _Korarchaeota_-specific Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes KR515R/KR565R. The undulated cell shape results from drying of the specimen on gelatin coated slides before hybridization. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (B) Phase-contrast image of korarchaeal filaments after physical enrichment. (Scale bar, 5 μm.) (C) Scanning electron micrograph of purified cells. (D) Transmission electron micrograph after negative staining with uranyl acetate displaying the paracrystalline S layer. Cells are flattened, which increases their apparent thickness.

Cell Preparation and Genome Sequencing.

It was observed that filamentous cells hybridizing to probes KR515R/KR565R remained intact in the presence of high concentrations of SDS (up to 1%) in the hybridization buffer. This feature allowed highly enriched cell preparations to be made by exposing the Obsidian Pool enrichment culture to 0.2% (wt/vol) SDS (without cell fixation) followed by several washing steps and filtration through 0.45-μm syringe filters. PCR-amplified SSU rDNA sequences from SDS-treated filtered cell preparations showed that >99% of the clones sequenced (n = 180) were identical to the SSU rDNA sequence of pOPF_08 (see Fig. S3). Phase-contrast (Fig. 1B) and EM (Fig. 1C) showed the samples to be highly enriched for ultrathin filamentous cells with a diameter of 0.16–0.18 μm. DNA clone libraries were constructed from both SDS- and nonSDS- (libraries BHXI and BFPP, respectively) treated enrichment culture filtrates. A total of 23,000 and 11,520 quality sequencing reads from libraries BHXI and BFPP, respectively, were binned based on %GC content and read depth. Overlapping fosmid sequences containing the pOPF_08 SSU rRNA gene (Fig. S4) were used to guide the WGS assembly. Five large scaffolds with a read depth of ×8.4–9.9 were closed by PCR (further details are provided in SI Text). Single-nucleotide polymorphisms occur at a rate of ≈0.2% across the genome.

General Features.

The complete genome consists of a circular chromosome 1,590,757 bp in length with an average G+C content of 49% (Table 1). A single operon was identified that contains genes for the SSU and LSU rRNAs. Forty-five tRNAs were identified by using tRNAscan-SE (18). A total of 1,617 protein-coding genes were predicted with an average size of 870 bp. Of the predicted protein-coding genes, 72.4% included AUG; 17.6%, UUG; and 10% had GUG for start codons. The archaeal Clusters of Orthologous Groups (arCOGs) analysis (see below), combined with additional database searches, allowed the assignment of a specific biological function to 998 (62%) predicted proteins; for another 246 proteins (15%), biochemical activity but not biological function could be predicted, and for the remaining 373 (23%) proteins, no functional prediction was possible, although many of these are conserved in some other archaea and/or bacteria.

Table 1.

General features of the Ca. K. cryptofilum genome

| Genome feature | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of bases | 1,590,757 |

| Coding density, % | 90.7 |

| G + C content, % | 49.0 |

| Total number of predicted genes | 1,665 |

| Protein coding genes | 1,617 |

| Average ORF length, bp | 870 |

| rRNA genes* | 3 |

| tRNA genes | 45 |

| Genes assigned to COGs | 1,401 |

| Genes assigned to arCOGs | 1,382 |

| Genes with function prediction | 998 |

| Genes with biochemical prediction only | 246 |

| Genes with unknown function or activity | 373 |

arCOGs.

The predicted proteins were assigned to arCOGs (19) (see SI Text, Dataset S1]. Of the 1,617 annotated proteins, 1,382 (85%) were found to belong to the arCOGs, a coverage that is slightly lower than the mean coverage of 88% for other archaea and much greater than the lowest coverage obtained for Nanoarchaeum equitans (72%) and Cenarchaeum symbiosum (58%). When the gene complement was compared with the strictly defined core gene sets for the Euryarchaeota and Crenarchaeota (i.e., genes that are represented in all sequenced genomes from the respective division, with the possible exception for C. symbiosum in the case of the Crenarchaeota, but that are missing in at least some organisms of the other division), a strong affinity with the Crenarchaeota was readily apparent. Specifically, Ca. K. cryptofilum possesses 169 of the 201 genes from the crenarchaeal core (84%) but only 33 of the 52 genes from the euryarchaeal core (63%). When the core gene sets were defined more liberally, i.e., as genes present in more than two-thirds of the genomes from one division and absent in the other division, the korarchaeote actually shared more genes with the Euryarchaeota than with Crenarchaeota (Table 2, Table S1). Seven proteins had readily identifiable bacterial but not archaeal orthologs, as determined by assigning proteins to bacterial COGs (20) (Table S2). Conceivably, the respective genes were captured via independent horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events from various bacteria. By contrast, no proteins were specifically shared with eukaryotes, to the exclusion of other archaea. The organism lacks only five genes that are represented in all sequenced archaeal genomes, namely, diphthamide synthase subunit DPH2, diphthamide biosynthesis methyltransferase, predicted ATPase of PP-loop superfamily; predicted Zn-ribbon RNA-binding protein, and small-conductance mechanosensitive channel.

Table 2.

Crenarchaeal and euryarchaeal arCOGs in Ca. K. cryptofilum

| arCOG | Category* | Function | Eu† | Cr‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 04447 | L | DNA polymerase II, large subunit | 27 | 0 |

| 04455 | L | DNA polymerase II, small subunit | 26 | 0 |

| 00872 | L | ERCC4-like helicase | 26 | 0 |

| 02610 | L | Rec8/ScpA/Scc1-like protein | 24 | 0 |

| 02258 | L | Subunit of RPA complex | 20 | 0 |

| 00371 | D | Chromosome segregation ATPase, SMC | 24 | 0 |

| 02201 | D | Cell division GTPase FtsZ | 26 | 0 |

| 01013 | J | Protein with L13E-like domain | 0 | 11 |

| 04327 | J | Ribosomal protein S25 | 0 | 13 |

| 04293 | J | Ribosomal protein S30 | 0 | 13 |

| 04305 | J | Ribosomal protein S26 | 0 | 13 |

| 04271 | K | RNA polymerase, subunit RPB8 | 0 | 12 |

| 00393 | K | Membrane-associated transcriptional regulator | 0 | 9 |

Energy Metabolism.

The predicted gene set suggests that Ca. K. cryptofilum grows heterotrophically, using a variety of peptide and amino acid degradation pathways. At least four ABC-type oligopeptide transporters and an OPT-type symporter could import short peptides, which more than a dozen peptidases could hydrolyze into amino acids. As in Pyrococcus spp., pyridoxal 5′-phosphate-dependent aminotransferases can convert amino acids to 2-oxoacids, while scavenging amines with α-keto-glutarate to form glutamate. Four ferredoxin-dependent oxidoreductases (specific for indolepyruvate, pyruvate, 2-oxoglutarate, or 2-oxoisovalerate) could oxidize and decarboxylate the 2-oxoacids, producing acyl-CoA molecules. Four acyl-CoA synthetases can convert this thioester bond energy into phosphoanhydride equivalents. Six aldehyde:ferredoxin oxidoreductase metalloenzymes could oxidize aldehydes derived from these amino acids. Pyruvate could be degraded by this pathway or by a homolog of pyruvate formate lyase. The only terminal reduction reaction predicted from the genome sequence is hydrogen production, apparently catalyzed by two soluble [NiFe]-hydrogenases. An archaeal-type proton-transporting ATP synthase would convert proton motive force produced by anaerobic respiration into ATP. However, in contrast to the system proposed for Pyrococcus furiosus, Ca. K. cryptofilum lacks a membrane-bound proton-translocating hydrogenase (21). Therefore, proton translocation must occur through the NADH:quinone oxidoreductase complex or a system that might involve homologs of the methanogen _hdrABC_-type heterodisulfide reductase complex. A ferredoxin:NADP oxidoreductase, three flavin reductases, and two electron transfer flavoproteins could mediate electron transfer to the respiratory chain. The korarchaeote also encodes a homolog of a single subunit [Ni-Fe] carbon monoxide dehydrogenase and its accessory proteins in a cluster of methanogen-like genes. Although the physiological role of these proteins in methanogens is unknown, they might confer the ability to oxidize CO produced under anaerobic conditions (22). There is no cytochrome c and no evidence of the dissimilatory reduction of sulfur, sulfite, sulfate, nitrate, nitrite, iron, formate, or oxygen. An abundance of iron-sulfur proteins and free radical initiating enzymes and the lack of oxidases suggest a strictly anaerobic lifestyle.

Central Metabolism.

A partial citric acid cycle is present that includes 2-oxoglutarate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase, succinyl-CoA ligase, succinate dehydrogenase, fumarase, malate dehydrogenase, aconitase, and malic enzyme. These enzymes could be used either for the degradation or for the biosynthesis of glutamate. The organism also encodes the components of a serine hydroxymethyltransferase and glycine cleavage system. One-carbon units from this pterin-dependent pathway are used to produce methionine from homocysteine. The genome encodes few carbohydrate transporters and no hexokinase, although it has a complete pathway for glycolysis from glucose 6-phosphate or for gluconeogenesis. There are no enzymes for the classical or modified Entner–Doudoroff pathways that are found in many Crenarchaeota. The organism does have a modified ribulose monophosphate pathway to produce ribose 5-phosphate (23) and a standard pyrimidine biosynthetic pathway. However, it lacks genes for purine nucleotide biosynthesis. Finally, an extensive set of UDP-sugar biosynthesis proteins and glycosyltransferases suggests the presence of glycosylated proteins and lipids. Although Ca. K. cryptofilum appears to be a proficient peptide degrader, it has an extensive set of amino acid biosynthesis enzymes (see SI Text). However, many genes are missing for coenzyme biosynthesis that are conserved in most of the other archaea. For CoA biosynthesis, it lacks the bifunctional phosphopantothenoylcysteine synthetase/decarboxylase that is found in all other sequenced archaeal genomes except for N. equitans and Thermofilum pendens (24). In addition, pathways for riboflavin, pterin, lipoate, porphyrin, and quinone biosynthesis are incomplete.

DNA Replication and Cell Cycle.

For initiating chromosome replication, two distinct orc1/cdc6 homologues and a single minichromosome maintenance protein complex are present along with genes encoding single-stranded binding protein and primase (PriSL). The genome encodes multiple DNA-dependent DNA polymerases, including two family B type enzymes and both the large and small subunits of a euryarchaeal type II polymerase. Genes for the sliding clamp (PCNA), PriSL, and a gins15 ortholog (25) are clustered with genes for the large subunit of the type II polymerase. A simplified clamp loader complex encodes the large and small subunits of replication factor C. Predicted chromatin-associated proteins include Alba and two H3-H4 histones. Like all known hyperthermophiles, reverse gyrase is present.

Ca. K. cryptofilum possesses several genes related to the ParA/MinD family of ATPases involved in chromosome partitioning and SMC-like proteins involved in chromosome segregation. The gene for this ATPase is part of a predicted operon that also includes genes for an FtsK-like ATPase (HerA) and two nucleases, proteins that are thought to comprise the basic machinery for DNA pumping (26). The organism appears to use the euryarchaeal mechanism for cell division, as indicated by the presence of seven genes encoding cell division GTPases (FtsZ; Fig. S5) (27). One of the ftsZ genes is included in a conserved euryarchaeal gene cluster containing secE, nusG, and several ribosomal protein genes (28, 29). In addition, five paralogous ftsZ genes are present in a seven-gene cluster that also includes a putative adapter protein (30).

Transcription and Translation.

Ca. K. cryptofilum possesses a full complement of archaeal DNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RNAP) subunits. The rpoA and rpoB genes encoding the largest subunits of the RNAP are intact. In addition to the typical archaeal RNAP subunits, a coding region of 110 aa was identified with limited sequence similarity to the RPB8 subunit of the eukaryotic RNAP. Subsequent in-depth analysis has shown that an ortholog of RPB8, previously thought to be missing in archaea, is also encoded by all sequenced genomes of hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota (31). The RPB8 ortholog resides in a putative operon with the eukaryotic-like transcription factor, TFIIIB. To initiate basal transcription, archaeal homologues for TATA-binding protein, transcription factor B (TFB), and transcription factor E (TFE) are present. Transcriptional regulators are of the bacterial/archaeal type, with the XRE, TrmB, ArsR, PadR-like, CopG, Lrp/AsnC, and MarA families represented in the genome.

The rRNA operon contains a SSU (16S) and a LSU (23S), which harbors an intron-encoded LAGLIDADG-type homing endonuclease similar to crenarchaeal homologues (32). A total of 33 LSU ribosomal proteins (r-proteins) and 27 SSU r-proteins are present. Notably, r-proteins S30e, S25e, S26e, and L13e that are conserved in the Crenarchaeota but are absent in Euryarchaeota (33) were identified. In contrast, large subunit r-proteins L20a, L29, and L35ae are missing from the genome.

The tRNA set consists of one initiator tRNA and 45 nonredundant elongator tRNAs. An unusual tRNAIle with an UAU anticodon is predicted to decode the ATA codon instead of a modified CAU commonly found in archaea (with the exception of N. equitans) (34). Both selenocysteine and pyrrolysine-specific tRNAs are absent. Four tRNA genes contain an intron located one base downstream of the anticodon and one tRNA gene (tRNASer CGA) contains an intron in the D-loop. The structural splicing motifs found at all five exon-intron junctions and the corresponding homomeric splicing endonuclease appear to reflect the conserved splicing mechanism found in Euryarchaeota (35). Also similar to some Euryarchaeota, the universal G-1 residue found at the 5′ terminus of tRNAHis is not encoded but is predicted to be added posttranscriptionally by a guanylyltransferase. The genome encodes archaeal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases for all of the amino acids except glutaminyl-tRNA formation, which is mediated via the tRNA-dependent transamidation pathway by using the GatD and GatE proteins (36). The LysRS is of the class I type and a homodimeric GlyRS is present. The SerRS is the common type rather than the rarer version found in some methanogens (37). However, ThrRS appears to be a bacterial type and was likely acquired through a HGT event.

Phylogeny and Evolutionary Genomics.

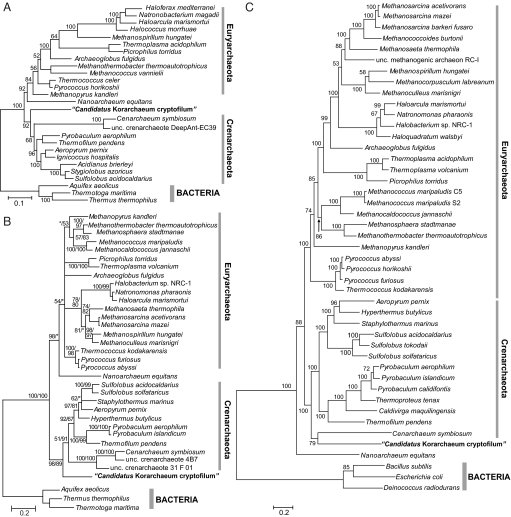

We performed a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis based on combined large and small rRNA subunits, conserved single-gene markers, and conserved concatenated proteins. Collectively, these results demonstrate that Ca. K. cryptofilum represents a deeply diverged archaeal lineage with affinity to the Crenarchaeota. Combined SSU+LSU rRNA subunit trees supported a deep crenarchaeal position (Fig. 2A). Likewise, the maximum-likelihood-based phylogeny of elongation factor 2 (EF2) homologues from archaeal genomes or environmental fosmid sequences corresponded with the rRNA tree (Fig. 2B). Phylogenetic analysis of 33 concatenated r-proteins and three large RNAP subunits clustered the korarchaeote with C. symbiosum in a deep branch joining the hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota (Fig. 2C). However, this grouping could be a long branch attraction artifact, and a statistical test showed that a basal position of Ca. K. cryptofilum identical to that in Fig. 2 A and B could not be ruled out. See SI Text for separate RNAP subunit and r-proteins phylogenies with compatibility testing.

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Ca. K cryptofilum. (A) Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of combined (SSU + LSU) rRNAs rooted with corresponding bacterial sequences. Numbers at the nodes indicate bootstrap support. (B) Archaeal phylogeny based on translation EF2 proteins rooted with bacterial homologs. The numbers indicate bootstrap support for PhyML/consensus posterior probability (Phyloblast), an asterisk indicates <50 support. Where both values were <50, the branch was collapsed. Also see Fig. S6. (C) Maximum-likelihood tree made from aligned sequences of 33 universally conserved ribosomal proteins and the three largest RNA polymerase subunits, RpoA, RpoB, and RpoD. Bootstrap support numbers are given at the nodes as a percentage (n = 10,000). (Scale bars represent the average number of substitutions per residue.)

Discussion

Capturing a Korarchaeal Genome.

Critical improvements in cultivation and in situ identification were necessary to resolve a complete korarchaeal genome. The ultrathin filamentous organisms hybridizing to _Korarchaeota_-specific probes displayed a thinner and generally longer morphology than described for pJP27-type korarchaeote (38). It is not known whether the morphological discrepancies are because of differences in the enrichment conditions, hence growth rate, or whether variation in cell shape occurs among closely related species. Nevertheless, SDS concentrations that are generally 5- to 50-fold higher than those typically required for FISH analyses of hyperthermophilic archaea (39) were necessary for optimal probe penetration. The structural integrity of Ca. K. cryptofilum in the presence of surfactants is likely attributed to the densely packed S-layer revealed through EM studies (Fig. 1D). Exploiting this feature allowed the filamentous cells to be sufficiently purified for WGS sequencing and assembly into a single contiguous chromosome. The proposed genus, Korarchaeum gen. nov., stems from the originally proposed phylum designation by Barns et al. (3), which is derived from the Greek noun koros or kore, meaning “young man” or “young woman,” respectively; and the Greek adjective archaios, for “ancient.” The proposed species name, cryptofilum sp. nov., is derived from the Greek adjective, kryptos, meaning “hidden” and the Latin noun filum, “a thread.”

Metabolism.

Determining the growth requirements in detail for Ca. K. cryptofilum was not possible, because the organism could be propagated only in a complex enrichment culture. Isolation attempts using Gelrite plates, dilution series, or optical tweezers were unsuccessful. However, the major aspects of the metabolism could be reconstructed from the predicted set of protein-coding genes, which suggest an obligately anaerobic, heterotrophic lifestyle with peptides serving as the principal carbon and energy source. In agreement with the predicted metabolism, the enrichment culture was supplied with peptone and traces of yeast extract as the primary carbon and energy source under strictly anaerobic conditions. Anaerobic peptide utilization is a common metabolic strategy among hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota and Euryarchaeota (40) and has been characterized in detail in the model organism Pyrococcus furiosus (41–44). However, Ca. K. cryptofilum apparently differs from other known hyperthermophiles in lacking the ability to use exogenous electron acceptors such as oxygen, nitrate, iron, or sulfur (45). Protons appear to be the primary acceptor for ferrodoxin-shuttled electrons. To avert possible growth inhibition, removal of molecular hydrogen by flushing with N2/CO2 gas or by possible hydrogen consuming members of the enrichment community such as Archaeoglobus and Thermodesulfobacterium spp. might have improved cell growth. The organism also appears to lack complete pathways for the de novo synthesis of several cofactors, which may prevent growth in axenic cultures. These coenzymes must be scavenged from the environment or the organism has evolved alternative modes for producing them. Microbial communities forming high-density mats composed of filamentous cells have yielded the highest number of amplified korarchaeal SSU rDNAs (9–11). Some essential nutrients for growth might be supplied in situ by other mat-forming organisms.

Evolutionary Considerations.

Independent phylogenetic analyses based on combined SSU + LSU rRNA, elongation factor 2 (EF-G/EF-2), and concatenated r-proteins + RNAP subunit sequences are compatible with the notion of the Korarchaeota being a deeply branching lineage with affinity to the Crenarchaeota (Fig. 2). This genome-based assessment corroborates a previous phylogenetic analysis based on a robust set of archaeal environmental SSU rDNA sequences (46). The apparent relationship between the Korarchaeota and a member of the marine group 1 Crenarchaeota suggested by the phylogeny of concatenated r-protein + RNAP subunits (Fig. 2C) is of potential interest. Based on comprehensive phylogenetic analyses and gene content comparisons, the mesophilic Crenarchaeota have recently been proposed to form a separate major phylum within the Archaea (47). The apparent affinity between C. symbiosum and Ca. K. cryptofilum presented in our analysis remains to be validated, because whole-genome phylogenetic reconstructions are based on a limited number of available archaeal genomes.

The genome revealed a pattern of orthologs that suggests an early divergence within the archaeal domain. The complement of information processing and cell cycle components appears to be a hybrid, with proteins composing the ribosome and RNAP shared, primarily, with Crenarchaeota, whereas functions involving tRNA maturation, DNA replication/repair, and cell division being more typical of the Euryarchaeota (Table 2). This complex pattern could have resulted from a combination of vertically inherited traits from ancestral organisms supplemented by HGT events. Recent genome analyses have shown that genes believed to be exclusive to the Euryarchaeota are also present in some crenarchaeotes. For example, a type II DNA polymerase and a divergent ftsZ homologue are present in Cenarchaeum symbiosum (48), and histones are also found in mesophilic and some hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota (49, 50). It remains to be determined whether these genes were vertically inherited from a common archaeal ancestor or were acquired horizontally from members of the Euryarchaeota or Bacteria (51). The euryarchaeal type features found in Ca. K. cryptofilum are generally more similar to those found in thermophilic and hyperthermophilic Euryarchaeota (Table S3). The presence of several mobile elements in the genome certainly suggests that the gene content may have been influenced by HGT (SI Text). Sequencing additional archaeal genomes will aid in determining whether the amalgam of cren- and euryarchaeal characteristics present in the korarchaeal genome represents is an ancient feature or resulted from a combination of HGT and gene loss events. More than a decade after the Korarchaeota were introduced based on rDNA sequences (2, 3), identifying Ca. K. cryptofilum and sequencing its genome have provided a perspective into the biological diversity of these elusive organisms and the genomic complexity of the archaeal domain.

Materials and Methods

Sample Collection and Cultivation.

Sediment and water samples were collected by B.P.H. from Obsidian Pool, YNP, and ranged from 78°C to 92°C with pH ≈6.5. The cultivation conditions for the Obsidian Pool enrichment culture were similar to those described in ref. 38. For details, see SI Text.

FISH Analysis.

FISH analysis was performed similar to that described in ref. 39. Cy3-labeled oligonucleotide probes KR515R (CCAGCCTTACCCTCCCCT) and KR565R (AGTATGCGTGGGAACCCCTC) provided optimal results. The hybridization solution containing 0.9 M NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 100 μg/ml sheared herring sperm DNA, 0.02 M Tris·HCl (pH 7.2), and 20% formamide (vol/vol). The wash buffer containing 0.23 M NaCl, 0.1% (wt/vol) SDS, and 0.02 M Tris·HCl (pH 7.2). For details see SI Text.

EM.

Cell pellets were immediately fixed in a solution containing 2.5% glutaraldehyde (EM grade) in 20 mM sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 6.5). EM method details are provided in SI Text.

Cell Purification.

Fermentor effluent was collected in sterile 2-liter glass bottles. Washed cells were briefly exposed to 0.2% SDS (wt/vol) and then washed three times with PBS (pH 7.2). Cell suspensions were then filtered through 0.45 μm syringe filters (MILLEX HV, Millipore) in 25-ml aliquots. The filtrate was centrifuged at 6,000 rpm in a Beckman JA-12 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA), for 30 min to collect the cells. See SI Text for detailed protocol.

Genome Sequencing and Assembly.

Library construction, sequencing, and assembly were performed at the Joint Genome Institute, Walnut Creek, CA (see SI Text).

Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetic Analyses.

The predicted protein-coding genes were compared against those from other genomes available in the Integrated Microbial Genomes analysis tool (52) and the National Center for Biotechnology Information database. arCOGs were analyzed by using the COGNITOR methods (19, 20, 53). An alignment of concatenated small and large subunit rRNA sequences (SSU + LSU rRNA) was constructed based on their conserved secondary structures and refined by hand. See SI Text for detailed information regarding phylogenetic analysis and tree construction.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments.

We gratefully acknowledge Carl R. Woese for his recognition of and continued dedication to the Archaea through his 80th birthday. We thank Norman Pace for insightful comments regarding preparation of the final manuscript. We also thank the Joint Genome Institute production sequencing team and Miriam Land with the Computational Biology Group at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Funding was provided by Verenium (formerly Diversa) Corporation (J.G.E and K.O.S.) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Support for genome sequencing and assembly was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy and the Joint Genome Institute Community Sequencing Program. Support was provided by the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and National Science Foundation Grant MCB-0546865 (to B.P.H.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (accession no. CP000968).

References

- 1.Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4576–4579. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barns SM, Fundyga RE, Jeffries MW, Pace NR. Remarkable archaeal diversity detected in a Yellowstone National Park hot spring environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barns SM, Delwiche CF, Palmer JD, Pace NR. Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9188–9193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auchtung TA, Takacs-Vesbach CD, Cavanaugh CM. 16S rRNA phylogenetic investigation of the candidate division “Korarchaeota.”. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:5077–5082. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00052-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takai K, Horikoshi K. Genetic diversity of archaea in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments. Genetics. 1999;152:1285–1297. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.4.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inagaki F, et al. Microbial communities associated with geological horizons in coastal subseafloor sediments from the Sea of Okhotsk. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7224–7235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7224-7235.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waters E, et al. The genome of Nanoarchaeum equitans: Insights into early archaeal evolution and derived parasitism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12984–12988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735403100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brochier C, Gribaldo S, Zivanovic Y, Confalonieri F, Forterre P. Nanoarchaea: Representatives of a novel archaeal phylum or a fast-evolving euryarchaeal lineage related to Thermococcales? Genome Biol. 2005;6:R42. doi: 10.1186/gb-2005-6-5-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reysenbach AL, Ehringer M, Hershberger K. Microbial diversity at 83 degrees C in Calcite Springs, Yellowstone National Park: Another environment where the Aquificales and “Korarchaeota” coexist. Extremophiles. 2000;4:61–67. doi: 10.1007/s007920050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hjorleifsdottir S, Skirnisdottir S, Hreggvidsson GO, Holst O, Kristjansson JK. Species composition of cultivated and noncultivated bacteria from short filaments in an Icelandic hot spring at 88 degrees C. Microb Ecol. 2001;42:117–125. doi: 10.1007/s002480000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skirnisdottir S, et al. Influence of sulfide and temperature on species composition and community structure of hot spring microbial mats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2835–2841. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.2835-2841.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takai K, Yoshihiko S. A molecular view of archaeal diversity in marine and terrestrial hot water environments. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1999;28:177–188. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marteinsson VT, et al. Discovery and description of giant submarine smectite cones on the seafloor in Eyjafjordur, northern Iceland, and a novel thermal microbial habitat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:827–833. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.2.827-833.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schrenk MO, Kelley DS, Delaney JR, Baross JA. Incidence and diversity of microorganisms within the walls of an active deep-sea sulfide chimney. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:3580–3592. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.6.3580-3592.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nercessian O, Reysenbach AL, Prieur D, Jeanthon C. Archaeal diversity associated with in situ samplers deployed on hydrothermal vents on the East Pacific Rise (13 degrees N) Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:492–502. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spear JR, Walker JJ, McCollom TM, Pace NR. Hydrogen and bioenergetics in the Yellowstone geothermal ecosystem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:2555–2560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409574102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teske A, et al. Microbial diversity of hydrothermal sediments in the Guaymas Basin: Evidence for anaerobic methanotrophic communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:1994–2007. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1994-2007.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: A program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makarova KS, Sorokin AV, Novichkov PS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Clusters of orthologous genes for 41 archaeal genomes and implications for evolutionary genomics of archaea. Biol Direct. 2007;2:33. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tatusov RL, et al. The COG database: An updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:41–54. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sapra R, Bagramyan K, Adams MWW. A simple energy-conserving system: Proton reduction coupled to proton translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:7545–7550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331436100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindahl PA, Graham DE. In: Nickel and Its Surprising Impact in Nature. Sigel A, Sigel H, Sigel RKO, editors. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2007. pp. 357–416. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orita I, et al. The ribulose monophosphate pathway substitutes for the missing pentose phosphate pathway in the archaeon Thermococcus kodakaraensis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4698–4704. doi: 10.1128/JB.00492-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson I, et al. Genome sequence of Thermofilum pendens reveals an exceptional loss of biosynthetic pathways without genome reduction. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:2957–2965. doi: 10.1128/JB.01949-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marinsek N, et al. GINS, a central nexus in the archaeal DNA replication fork. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:539–545. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iyer LM, Makarova KS, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Comparative genomics of the FtsK-HerA superfamily of pumping ATPases: Implications for the origins of chromosome segregation, cell division and viral capsid packaging. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5260–5279. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaughan S, Wickstead B, Gull K, Addinall SG. Molecular evolution of FtsZ protein sequences encoded within the genomes of archaea, bacteria, and eukaryota. J Mol Evol. 2004;58:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Faguy DM, Doolittle WF. Cytoskeletal proteins: The evolution of cell division. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R338–R341. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poplawski A, Gullbrand B, Bernander R. The ftsZ gene of Haloferax mediterranei: Sequence, conserved gene order, and visualization of the FtsZ ring. Gene. 2000;242:357–367. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00517-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye H, et al. Crystal structure of the putative adapter protein MTH1859. J Struct Biol. 2004;148:251–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koonin EV, Makarova KS, Elkins JG. Orthologs of the small RPB8 subunit of the eukaryotic RNA polymerases are conserved in hyperthermophilic Crenarchaeota and “Korarchaeota.”. Biol Direct. 2007;2:38. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cann IK, Ishino S, Nomura N, Sako Y, Ishino Y. Two family B DNA polymerases from Aeropyrum pernix, an aerobic hyperthermophilic crenarchaeote. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5984–5992. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.19.5984-5992.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lecompte O, Ripp R, Thierry JC, Moras D, Poch O. Comparative analysis of ribosomal proteins in complete genomes: An example of reductive evolution at the domain scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:5382–5390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marck C, Grosjean H. tRNomics: Analysis of tRNA genes from 50 genomes of Eukarya, Archaea, and Bacteria reveals anticodon-sparing strategies and domain-specific features. RNA. 2002;8:1189–1232. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202022021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parrish J, et al. Mitochondrial endonuclease G is important for apoptosis in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412:90–94. doi: 10.1038/35083608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feng L, Sheppard K, Tumbula-Hansen D, Söll D. Gln-tRNAGln formation from Glu-tRNAGln requires cooperation of an asparaginase and a Glu-tRNAGln kinase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8150–8155. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim HS, Vothknecht UC, Hedderich R, Celic I, Söll D. Sequence divergence of seryl-tRNA synthetases in archaea. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6446–6449. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6446-6449.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burggraf S, Heyder P, Eis N. A pivotal Archaea group. Nature. 1997;385:780. doi: 10.1038/385780a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burggraf S, et al. Identifying members of the domain Archaea with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.9.3112-3119.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly RM, Adams MW. Metabolism in hyperthermophilic microorganisms. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:247–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00871643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma K, Schicho RN, Kelly RM, Adams MW. Hydrogenase of the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus is an elemental sulfur reductase or sulfhydrogenase: Evidence for a sulfur-reducing hydrogenase ancestor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5341–5344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mai X, Adams MW. Indolepyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. A new enzyme involved in peptide fermentation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:16726–16732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blamey JM, Adams MW. Purification and characterization of pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1161:19–27. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(93)90190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schut GJ, Brehm SD, Datta S, Adams MW. Whole-genome DNA microarray analysis of a hyperthermophile and an archaeon: Pyrococcus furiosus grown on carbohydrates or peptides. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:3935–3947. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.13.3935-3947.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huber R, Huber H, Stetter KO. Towards the ecology of hyperthermophiles: Biotopes, new isolation strategies and novel metabolic properties. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:615–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robertson CE, Harris JK, Spear JR, Pace NR. Phylogenetic diversity and ecology of environmental Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:638–642. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brochier-Armanet C, Boussau B, Gribaldo S, Forterre P. Mesophilic crenarchaeota: Proposal for a third archaeal phylum, the Thaumarchaeota. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:245–252. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hallam SJ, et al. Genomic analysis of the uncultivated marine crenarchaeote Cenarchaeum symbiosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18296–18301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608549103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cubonova L, Sandman K, Hallam SJ, Delong EF, Reeve JN. Histones in crenarchaea. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5482–5485. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5482-5485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandman K, Reeve JN. Archaeal histones and the origin of the histone fold. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2006;9:520–525. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lopez-Garcia P, Brochier C, Moreira D, Rodriguez-Valera F. Comparative analysis of a genome fragment of an uncultivated mesopelagic crenarchaeote reveals multiple horizontal gene transfers. Environ Microbiol. 2004;6:19–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Markowitz VM, et al. The integrated microbial genomes (IMG) system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D344–D348. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tatusov RL, Koonin EV, Lipman DJ. A genomic perspective on protein families. Science. 1997;278:631–637. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information