Diaphragm and lubricant gel for prevention of HIV acquisition in southern African women: a randomised controlled trial (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2008 Jun 30.

Summary

Background

Female-controlled methods of HIV prevention are urgently needed. We assessed the effect of provision of latex diaphragm, lubricant gel, and condoms (intervention), compared with condoms alone (control) on HIV seroincidence in women in South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Methods

We did an open-label, randomised controlled trial in HIV-negative, sexually active women recruited from clinics and community-based organisations, who were followed up quarterly for 12–24 months (median 21 months). All participants received an HIV prevention package consisting of pre-test and post-test counselling about HIV and sexually transmitted infections, testing, treatment of curable sexually transmitted infections, and intensive risk-reduction counselling. The primary outcome was incident HIV infection. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00121459.

Findings

Overall HIV incidence was 4.0% per 100 woman-years: 4.1% in the intervention group (n=2472) and 3.9% in the control group (n=2476), corresponding to a relative hazard of 1.05 (95% CI 0.84–1.32, intention-to-treat analysis). The proportion of women using condoms was significantly lower in the intervention than in the control group (54% vs 85% of visits, p<0.0001). The proportions of participants who reported adverse events (60% [1523] vs 61% [1529]) and serious adverse events (5% [130] vs 4% [101]) were similar between the two groups.

Interpretation

We observed no added protective benefit against HIV infection when the diaphragm and lubricant gel were provided in addition to condoms and a comprehensive HIV prevention package. Our observation that lower condom use in women provided with diaphragms did not result in increased infection merits further research. Although the intervention seemed safe, our findings do not support addition of the diaphragm to current HIV prevention strategies.

Introduction

An estimated 39.5 million people worldwide were living with HIV/AIDS at the end of 2006.1 Southern Africa is considered the epicentre of the pandemic, and about 20% of adults in Zimbabwe and South Africa are infected with HIV. In this region, women have up to twice the risk of HIV infection compared with men.2 Because of sociocultural constraints and power differentials in gender roles, these women are often unable to negotiate the use of male condoms, a key component of HIV prevention strategies.3–7 Simple low-cost prevention methods that women can initiate and control could have a substantial effect on the management of the HIV epidemic.

Although the development of new female-controlled methods is well underway, availability of an effective microbicide for prevention of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is still years away, and several trials of candidate gels have recently been stopped early with disappointing results.8–14 The diaphragm has the potential advantage of a long history of use, and has been approved and used globally as a contraceptive method. The device is worn internally, covers the cervix, and blocks semen from ascending to the upper genital tract. Although it is no longer a widely used contraceptive, observational studies in several developing countries have shown high acceptability of the diaphragm in the general population.15–20 Diaphragms are simple, reusable, and stable under varying environmental conditions, posing no disposal problems and little difficulty with cleaning and storage. The device can be used covertly and does not necessitate cooperation or knowledge from the male partner.21,22

Evidence suggests that physical barriers covering the cervix offer safe and effective protection against HIV and STIs that exacerbate risk of HIV infection. Neisseria gonorrhoeae, _Chlamydia trachomati_s, and human papillomavirus (HPV) preferentially infect the cervix and upper genital tract, and results of observational studies suggest that diaphragm users have a reduced risk of these cervical STIs, pelvic inflammatory disease, and HPV-associated cervical neoplasia.8,23 Unlike the multilayered vaginal squamous epithelium, the cervix has only one layer of delicate columnar epithelial cells, making target cells more accessible to HIV. The transformation zone at the cervix (the area of demarcation between columnar and squamous epithelium) has been shown to have a greater concentration of HIV-receptor susceptible cells close to the mucosal surface—including CD4-positive T lymphocytes (CD4 cells), Langerhans cells, macrophages, and cells with CCR5, CXCR4s, and Fc-γ receptors23–27—compared with vaginal epithelium. In the present Methods for Improving Reproductive Health in Africa (MIRA) trial, we did a multisite, randomised controlled open-label study to assess the effectiveness of the latex diaphragm with a lubricant gel in preventing heterosexual acquisition of HIV among women in southern Africa, compared with provision of condoms alone.

Methods

Study design and participants

Between September, 2003, and September, 2005, we recruited sexually active (an average of at least four sex acts per month) women aged 18–49 years to join the MIRA trial in Durban and Johannesburg, South Africa, and Harare, Zimbabwe. Participants who met protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria (see panel 1) were then randomised into one of two groups: the intervention group, who received a clinician-fitted diaphragm (All-Flex Arcing Spring diaphragm; Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Raritan, NJ, USA), a supply of lubricant gel (Replens, Lil’ Drug Store Products, Cedar Rapids, IA, USA) and male condoms; and the control group, who received male condoms only. All participants received a comprehensive HIV prevention package consisting of HIV/STI pre-test and post-test counselling, treatment of curable, laboratory-diagnosed STIs, and intensive risk reduction counselling, which emphasised condom negotiation, and was tailored to each participant’s individual circumstances. Pre-test and post-test counselling was individual and confidential, and was offered by qualified research counsellors at the research clinic sites, in accord with guidelines of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Panel 1: MIRA protocol inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Aged 18–49 years*

- Sexually active (defined as an average of four acts per month)

- HIV-negative

- C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae negative or treated† at enrolment

- Healthy cervix

- Intending to live in study area for 24 months

- Willing to be randomised

- Willing to provide informed consent

Exclusion criteria

- Known sensitivity or allergy to latex

- History of toxic shock syndrome

- Currently pregnant or wanting to be pregnant in the next 24 months

- Refused treatment for STI/RTI diagnosed at enrolment

- No cervix (total hysterectomy)

- Epithelial disruptions or lesions

- Recent pelvic surgery or pregnancy outcome (within 6 weeks)

- Unable (within five attempts) or unwilling to insert diaphragm correctly

- Illicit drug use or recent blood transfusions (within past 12 months)

- Co-enrolment in other trials

- Unable to speak the study languages (English, Shona, Sotho, Zulu)

- Condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would constitute contraindications to participation in the study or would compromise ability to comply with the study protocol, such as a major psychiatric disorder

- Did not meet eligibility criteria within five screening or five enrolment visits

RTI = reproductive tract infection. *In November, 2003, 3 months after the beginning of screening, the upper age limit was set at 49 years; previously, women aged 50 years or older had been enrolled into the study. †Single-dose treatment taken at enrolment qualified women as eligible participants.

The randomisation scheme was developed by Ibis Reproductive Health, and used randomly permuted blocks of sizes eight, ten, and 12, stratified by site. Sealed, opaque randomisation envelopes were stored in a secure, central location at each clinic. At the point of randomisation, the designated staff member retrieved the next sequential envelope, and both the staff member and the participant signed the envelope to verify that it was intact. The participant then opened the envelope for their assignment. The study was open label, since no placebo could be used for a diaphragm. Data were managed at the Center for International Data Evaluation and Analysis at the University of California at San Francisco. Data were electronically faxed from the clinic sites directly into a database system. The investigators and co-ordinators were able to access individual records for quality control purposes, but all information identifying the study arm was coded. Investigators and study statisticians were not allowed to examine any data by study arm until unblinding in early February, 2007, when the final analysis began.

Participants were followed quarterly from September, 2003, to December, 2006. The follow-up period for the study was designed to be staggered, with the first cohort of enrolled participants followed up for 24 months, the last enrolled followed for 12 months, and an overall average of 18 woman-months of follow-up per participant.

Women were recruited from family planning, well-baby, and general health clinics, and from community-based organisations, through printed media and radio. In Zimbabwe, the study was done in two clinics within 30 km of Harare: Chitungwiza, a peri-urban municipality; and Epworth, a slightly poorer and less developed suburb. In Durban, the study was undertaken from a peri-urban clinic in Umkomaas and a less urbanised clinic in Botha’s Hill. In Johannesburg, the study clinic was located on the campus of the Perinatal HIV Research Unit of the Chris Hani Barangwanath Hospital in Soweto, a large urban township area.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of California at San Francisco Institutional Review Board Committee on Human Research, and by the ethics review committees at all local institutions and collaborating organisations, including the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe, Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, and Western Institutional Review Board. An independent external audit, sponsored by Ibis Reproductive Health, was done by the Quintiles Corporation in November 2005, after study accrual was completed.

Procedures

At screening, we obtained verbal consent to assess initial eligibility, followed by written informed consent for screening procedures, including diagnostic testing and answering an interviewer-administered questionnaire on demographics and sexual behaviour. Participants received counselling before tests for HIV and STIs, and provided a urine specimen for PCR testing for N gonorrhoeae, _C trachomati_s and Trichomonas vaginalis (Roche Pharmaceuticals, Branchburg, NJ, USA). Two HIV rapid tests were done on whole blood samples from finger-prick or venipuncture by use of Determine HIV-1/2 (Abbott Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) and Oraquick (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA, USA). All participants were notified of their HIV test results and received post-test counselling, condoms, and referral to supporting services, as needed. Discordant results of rapid tests were confirmed on serum samples by ELISA (Vironostika, Biomerieux, Durham, NC, USA; BioRad, Redmond, WA, USA; or AxSYM HIV Ag/Ab Combo assay, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). The enrolment visit was scheduled within 2 weeks for participants who met the initial eligibility criteria.

At their enrolment visit, participants provided written informed consent, had a pelvic examination, provided a blood sample to be used in tests for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin [RPR] and Treponema pallidum haemagglutinin [TPHA], Randox Laboratories, Crumlin, UK) and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV2; ELISA, FOCUS Diagnostics, Cypress, CA, USA), and urine for pregnancy testing. Women who tested positive for syphilis at enrolment were treated and kept in the study. Because of the high prevalence (>50%) of HSV2 in study areas, and the logistical challenges of identifying individuals who were negative for both HSV2 and HIV, we did not screen out individuals with prevalent HSV2 infection. On the day of enrolment, if women had not had an HIV test done within the past 14 days or tests for N gonorrhoeae, _C trachomati_s, and T vaginalis done within the past 30 days, they were required to be re-tested before being eligible for randomisation.

To ensure that women in the intervention group were not inherently better at using the diaphragm than those in the control group, all women were fitted for a diaphragm before randomisation, received a demonstration of diaphragm placement on a pelvic model with instructions on use, practised diaphragm insertion on themselves, and were assessed for correct insertion and removal of the device. Women enrolled in the trial completed an Audio Computer Assisted Self-Interviewing (ACASI) baseline questionnaire on demographics, sexual behaviour, and product use.

After randomisation and ACASI, women in the intervention group were counselled to insert the diaphragm into their vagina at any time that was convenient to them before coitus, and to leave it in place for at least 6 h after sex. They were given detailed instructions on maintenance, cleaning, and storage of their diaphragm. Women were asked to empty an applicator of gel (about 2.5 g) into the dome of the diaphragm at the time of insertion, to spread gel onto the rim to facilitate insertion, and to insert another applicator of gel into the vagina before each act of vaginal sex. At each visit, women received a 3-month supply of gel, and were counselled that the effectiveness of the diaphragm and lubricant gel for the prevention of HIV infection was not known. To prevent HIV, they were asked to use condoms regardless of whether or not they used the diaphragm and lubricant gel. Participants were also told that they should not use the diaphragm and lubricant alone as a method of contraception. The diaphragm is approved for contraception when used with a spermicide (typical effectiveness 84%), but its effectiveness without nonoxynol-9 has not been fully established28,29 (nonoxynol-9 is not indicated for use in settings of high HIV prevalence, and therefore was not used in this study). Women were advised to use other contraceptive methods and were provided with hormonal contraceptives through the clinic. They were encouraged to return to the clinic if they experienced any problems or needed more study products.

Panel 2: MIRA study products.

Diaphragm: All-Flex Arcing Spring diaphragm (Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical)

Moulded, buff-coloured, natural rubber vaginal diaphragm. Contains a distortion-free, dual spring-within-a-spring that provides arcing action.

Gel: Replens Long-Lasting Vaginal Moisturizer (Lil’ Drug Store Products)

An over-the-counter gel that has been marketed to postmenopausal women for treating symptoms of vaginal dryness and atrophy, and has a positive effect on the maturation of the vaginal epithelium.30 Ingredients are purified water, glycerin, mineral oil, polycarbophil, carbomer 934P, hydrogenated palm oil glyceride, sorbic acid, methylparaben, and sodium hydroxide. Replens is not a known contraceptive. Although it is considered an inactive lubricant, it has weak acid-buffering activity. It has been used as a placebo in microbicide safety and effectiveness trials and has also been shown to provide some protection against herpes simplex virus 2 in a mouse model and to inactivate HIV in vitro.31–36

Distribution

Both study products (diaphragm and gel) were removed from their original packaging and only study-specific instructions for use were given to participants. Diaphragms were distributed in nine sizes, ranging from 55 mm to 95 mm, in 5 mm increments. The gel was distributed in 35 g tubes (14 applications per tube) with one reusable applicator per tube.

At all visits, participants in both study groups received counselling on risk reduction and as many male condoms as desired. Counsellors emphasised that condoms are the only known method to prevent HIV and STIs, and that condoms should be used for every act of sex. Illustrated instruction sheets on use of diaphragms and male condoms were distributed to all women according to study arm assignment in all study languages. A statement about what is known and unknown about the effectiveness of condoms, diaphragms, and gel was included in the enrolment informed consent form, and women’s comprehension of this information was assessed with a questionnaire at the enrolment and month-12 visits. Study products are described in panel 2.

Participants returned 2 weeks after enrolment for resupply of products, for counselling, and to have any problems assessed. Thereafter, follow-up visits were scheduled quarterly to assess HIV and STI status, recent medical history, use of study products, and sexual behaviour, through a face-to-face clinician-administered questionnaire and ACASI. Women were counted as having attended their quarterly visit if they visited during the period from 14 days before, to 73 days after, the scheduled date. Clinicians addressed any medical problems; a pelvic examination and urinalysis or wet mount were done when clinically indicated, and treatment was provided when appropriate. Syphilis testing was repeated at the closing visit or if clinically indicated. HSV2 testing was repeated at the closing visit for women who were negative for HSV2 at enrolment.

Confirmatory laboratory testing was done for women with double-positive or inconsistent HIV rapid results with HIV ELISA. In cases of weakly reactive ELISA results, Western blot (BioRad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA) was used to corroborate ELISA test results. All participants were informed of their HIV status after each test. Women who seroconverted were able to continue participation in the study, and were scheduled for follow-up supportive counselling and referred to local psychosocial and clinical services. The study facilitated access to community-based psychosocial support programmes and to national care and antiretro-viral treatment programmes for all participants who were identified as HIV-positive after enrolment.

Statistical analyses

We selected a sample size of 4500 to provide 90% power to detect an intervention-related decrease in HIV incidence of at least 33%, significant at the 5% level. We assumed that incidence rates at the three sites ranged between 3.5% and 5% per year, that average adherence to diaphragms would be 80% in the intervention group, that the average yearly rate of loss to follow-up would be 7%, and that the maximum length of follow-up would be 24 months. Midway through the study, in June, 2005, before the first scheduled interim analysis, overall incidence of HIV in the first months of the study was noted to be lower than expected; we therefore increased the sample size to 5000.

An independent Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB), chosen and convened by the study investigators, was scheduled to meet once, when a third of the expected 300 HIV seroconversions had occurred. Prespecified stopping rules included lack of safety, futility, or efficacy. Statistical monitoring criteria were based on the Lan-Demets group sequential method with O’Brien-Fleming stopping boundaries to preserve the overall type-1 error rate at 5%.37,38 Based on the results of the first interim analysis, the DSMB requested another interim analysis, which was done when two-thirds of expected seroconversions had been reached, with a recommendation to complete the trial as planned.

The primary outcome was incident HIV infection. To confirm that women with HIV infection identified at their first follow-up visit were incident cases, we tested for viral nucleic acid by HIV DNA PCR (Amplicor HIV-1 DNA v1.5, Roche Molecular Systems, Branchburg, NJ, USA) from stored dried blood spot samples (S&S filter paper). At the South African sites, HIV RNA PCR tests (Amplicor HIV-1 MONITOR, v1.5, Roche Molecular Systems) were also done on stored plasma from the enrolment visit. Participants with a positive for HIV DNA PCR, HIV RNA PCR (>400 copies per μL), or both, were classified as having prevalent HIV infection at enrolment, and therefore were excluded from the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

HIV incident infection was defined as time from enrolment to seroconversion, on the basis of a discrete time scale determined by an individual’s quarterly visit schedule. For participants who seroconverted, the time of seroconversion was defined as the time of first positive HIV test result. For cases in which one or more visits were missed in the intervals between the last negative and first positive tests, the time of seroconversion was assumed to be the visit containing the midpoint between these two time points.

To minimise recall bias, we a priori selected product use at last sex as our primary measures of diaphragm use and of condom use in all analyses.39 For confirmatory purposes, we also assessed a measure of cumulative use of the methods since last study visit (always, sometimes, or never).

Selected baseline characteristics were compared between the groups to examine the effect of randomisation. In addition to safety assessments, we did an ITT and subgroup analyses, and a per-protocol analysis. All analyses were pre-specified in an analytical plan finalised before the group assignments were unblinded.

The primary analysis compared observed HIV incidence between the groups using a stratified Cox model for discrete time outcomes, including a binary indicator of group assignment as the only predictor variable, and with separate baseline hazards for each of the three study sites. This analysis was based on an ITT approach. Results of the primary analysis were summarised by the estimated relative hazard comparing HIV incidence in women in the intervention group to that in controls, with associated 95% CIs. We also did additional subgroup analyses to investigate the consistency of ITT results across categories of baseline characteristics selected a priori. Results were summarised by separate relative hazard estimates and 95% CIs for the effect of the intervention at each level of each of the baseline variables.

The per-protocol analysis repeated the between-group comparison of the primary outcome, excluding follow-up periods where participants in the intervention group did not report use of the diaphragm at last sexual contact. Person-time in the intervention group was included in this analysis if participants reported using the diaphragm without the lubricant gel. Person-time in the control group was included even if no condom use was reported, but was excluded if use of a diaphragm was reported.

For women in the intervention group, we assessed the marginal association between condom and diaphragm use, cumulatively across all follow-up visits, with generalised estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression.

Assessment of safety of the intervention was based on a comparison of the proportions of participants who reported reproductive tract-related, urinary tract-related or pregnancy-related adverse events or serious adverse events by study group.

This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00121459.

Role of the funding source

The sponsor of the study maintained oversight of the trial through regular progress reports and meetings with Investigators, and its program officer had input into key scientific decisions as a member of the Study Technical Advisory Committee. The sponsor had no other role in the data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The authors had access to all the data and shared final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

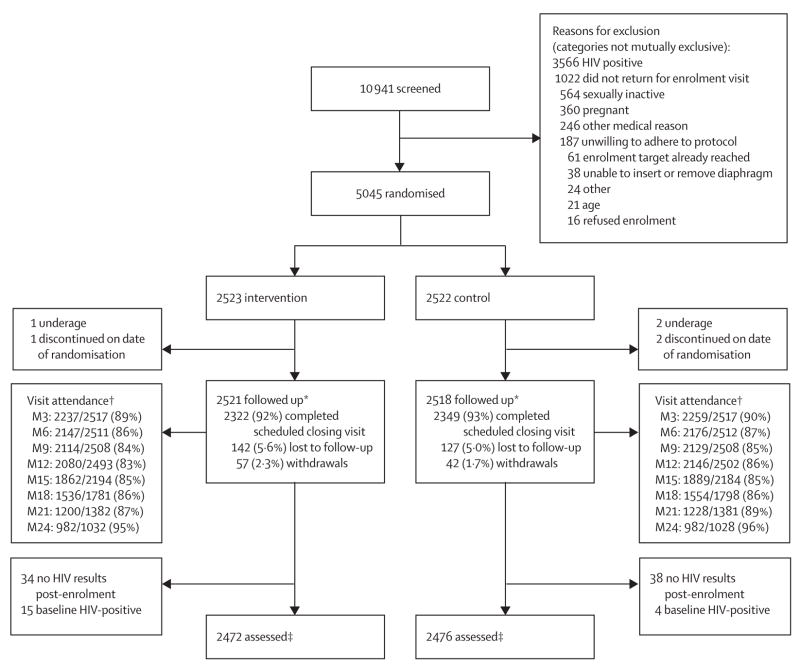

Figure 1 shows the trial profile. Rates of missed visits and discontinuation (due to early withdrawals or reaching scheduled closing visits), were similar between the groups throughout the follow-up period. The median duration of follow-up was 21 months (range 0–24). Of the 368 (7%) women who did not complete a closing visit as scheduled, 6% in the intervention group and 5% in the control group were classified as lost to follow-up, defined as participants who did not complete a closing visit (whether or not they had any interim follow-up data). 72 women did not contribute to the primary analysis because no endpoint HIV data were available. 19 women (15 intervention, four control) who were found to have been HIV-infected at enrolment were also excluded from further analyses. Thus, the final HIV-endpoint analytical dataset included 4948 women.

Figure 1. Trial profile.

Lost to follow up includes participants who might have had interim follow-up data but did not complete a closing visit. Withdrawals include participants who discontinued because of death (23) or who came back to study clinic and withdrew or were withdrawn early because of relocation (22), partner-related reasons (16), personal reasons (13), no time to participate (11), or other reasons (12). *Baseline sample. †M=month, data are number who attended/number expected; women who discontinued (withdrew early or completed the study on time) were removed from subsequent denominator. ‡Includes women confirmed to be HIV-negative at enrolment who had at least one subsequent HIV test result.

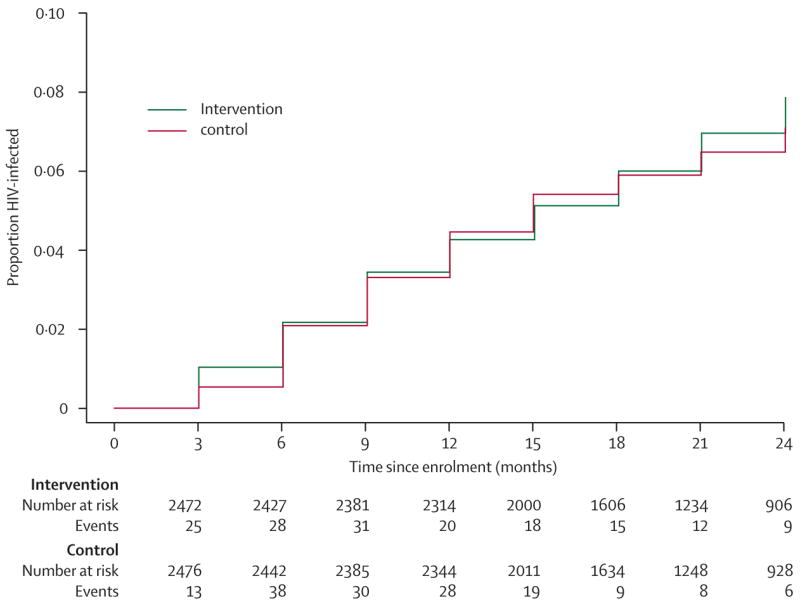

The distribution of baseline demographic characteristics and reported sexual behaviour were similar between the groups (table 1). Table 2 shows numbers of women who became HIV-positive during 7702 woman-years of follow-up, rates of seroconversion, and relative hazards of HIV acquisition for women in the intervention group, compared with controls (ITT). Rates of acquisition in the intervention group were similar to those in controls overall and at each site, with 95% CIs for relative hazards overlapping between the three sites. We also calculated the cumulative relative risk comparing the crude proportions of HIV infections between the two groups, which was identical to the overall relative hazard estimate reported in table 2 (data not shown). Figure 2 shows group-specific Kaplan-Meier estimates of the cumulative probability of HIV infection, which largely overlapped between the groups throughout follow-up.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics, reproductive history, and sexual behaviour

| Total (n=5039) | Intervention group (n=2521) | Control group (n=2518) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| ≤24 years | 1933 (38%) | 997 (40%) | 936 (37%) |

| 25–34 years | 1972 (39%) | 969 (38%) | 1003 (40%) |

| ≥35 years | 1133 (23%) | 554 (22%) | 579 (23%) |

| At least high school education | 2214 (44%) | 1133 (45%) | 1081 (43%) |

| Earned income in past year | 2813 (56%) | 1427 (57%) | 1386 (55%) |

| Employed | 1163 (23%) | 586 (23%) | 577 (23%) |

| Married | 2972 (59%) | 1485 (59%) | 1487 (59%) |

| Living together | 3402 (68%) | 1700 (67%) | 1702 (68%) |

| Language of screening form | |||

| English | 614 (12%) | 304 (12%) | 310 (12%) |

| Shona | 2492 (49%) | 1245 (49%) | 1247 (49%) |

| Zulu | 1702 (34%) | 855 (34%) | 847 (34%) |

| Sotho | 231 (5%) | 117 (5%) | 114 (5%) |

| Religion (Christian vs other/none) | 4712 (94%) | 2361 (94%) | 2351 (93%) |

| Lifetime number of sexual partners, mean (range) | 2 (1–30) | 2 (1–20) | 2 (1–30) |

| Age at first sex, mean (range) | 18 (10–31) | 18 (10–29) | 18 (11–31) |

| Coital frequency >3 times per week | 1743 (35%) | 883 (35%) | 860 (34%) |

| Partner circumcised | |||

| Yes | 1087 (22%) | 564 (22%) | 523 (21%) |

| No | 2945 (58%) | 1453 (58%) | 1492 (59%) |

| Don’t know | 995 (20%) | 499 (20%) | 496 (20%) |

| Tested positive for STI* | 794 (16%) | 387 (15%) | 407 (16%) |

| Tested positive for HSV2 at enrolment | 2947 (59%) | 1440 (57%) | 1507 (60%) |

| High behaviour risk† | 1440 (29%) | 703 (28%) | 737 (29%) |

| High partner risk‡ | 3447 (69%) | 1729 (69%) | 1718 (68%) |

| Used condom at last sex (at enrolment) | 3411 (68%) | 1693 (67%) | 1718 (68%) |

| Condom use in past 3 months at enrolment | |||

| Never | 1499 (30%) | 756 (30%) | 743 (30%) |

| Sometimes | 1959 (39%) | 1001 (40%) | 958 (38%) |

| Always | 1570 (31%) | 759 (30%) | 811 (32%) |

| Ever used diaphragm at screening | 3 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (<1%) |

| Current contraceptive use at screening | |||

| Long term§ | 304 (6%) | 150 (6%) | 154 (6%) |

| Injectable hormones | 1242 (25%) | 608 (24%) | 634 (25%) |

| Pill¶ | 1825 (36%) | 916 (36%) | 909 (36%) |

| Barrier[| | ](#TFN7) | 1024 (20%) | 532 (21%) |

| Other/none | 644 (13%) | 315 (13%) | 329 (13%) |

Table 2.

Summary of HIV seroconversions, overall and by site (n=4948)

| Total participants | Number of seroconversions (cumulative proportion*) | Woman-years of follow-up | Incidence (rate per 100 woman- years) | Relative hazard (95% CI), intervention vs control | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Sites | ||||||

| Overall | 4948 | 309 (6.2%) | 7702 | 4.0 | 1.05 (0.84–1.32)† | 0.65 |

| Intervention | 2472 | 158 (6.4%) | 3835 | 4.1 | ||

| Control | 2476 | 151 (6.1%) | 3867 | 3.9 | ||

| Harare, Zimbabwe | ||||||

| Overall | 2455 | 114 (4.6%) | 4150 | 2.7 | 1.20 (0.83–1.74) | 0.32 |

| Intervention | 1226 | 62 (5.1%) | 2066 | 3.0 | ||

| Control | 1229 | 52 (4.2%) | 2084 | 2.5 | ||

| Durban, South Africa | ||||||

| Overall | 1485 | 148 (10.0%) | 2162 | 6.8 | 0.95 (0.69–1.31) | 0.76 |

| Intervention | 743 | 72 (9.7%) | 1079 | 6.7 | ||

| Control | 742 | 76 (10.2%) | 1083 | 7.0 | ||

| Johannesburg, South Africa | ||||||

| Overall | 1008 | 47 (4.7%) | 1391 | 3.4 | 1.05 (0.60–1.87) | 0.86 |

| Intervention | 503 | 24 (4.8%) | 691 | 3.5 | ||

| Control | 505 | 23 (4.6%) | 700 | 3.3 |

Figure 2. Cumulative HIV probability of infection (Kaplan-Meier estimates) by group.

The estimated relative hazard of HIV acquisition was stable across each pre-defined baseline subgroup, with no unusual deviations, suggesting consistency in the estimated overall effect of the intervention (table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis by baseline characteristics, stratified by site (n=4948)

| Intervention group (events/woman-years) | Control group (events/woman-years) | Relative hazard, intervention vs control (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline age | |||

| ≤24 years | 87/1500 | 71/1394 | 1.12 (0.82–1.53) |

| 25–34 years | 51/1504 | 57/1592 | 0.95 (0.65–1.39) |

| ≥35 years | 20/829 | 23/881 | 0.94 (0.51–1.71) |

| Education | |||

| Less than high school | 83/2114 | 92/2173 | 0.95 (0.71–1.28) |

| At least high school | 75/1720 | 58/1691 | 1.22 (0.86–1.71) |

| Coital frequency (per week) | |||

| ≤3 times | 104/2448 | 104/2492 | 1.03 (0.79–1.36) |

| >3 times | 54/1388 | 47/1375 | 1.09 (0.74–1.61) |

| Regular partner circumcised | |||

| Yes | 35/819 | 28/765 | 1.18 (0.72–1.93) |

| No | 85/2258 | 74/2353 | 1.20 (0.88–1.64) |

| Don’t know | 38/750 | 47/741 | 0.78 (0.51–1.19) |

| Tested positive for STI* | |||

| Yes | 31/561 | 32/586 | 0.98 (0.60–1.60) |

| No | 127/3274 | 119/3281 | 1.07 (0.84–1.38) |

| Tested positive for HSV2 | |||

| Yes | 107/2169 | 108/2279 | 1.04(0.80–1.36) |

| No | 51/1665 | 43/1585 | 1.12 (0.74–1.68) |

| Behavioural risk† | |||

| Low | 108/2775 | 97/2728 | 1.09 (0.83–1.43) |

| High | 50/1051 | 52/1130 | 1.05 (0.71–1.54) |

| Partner risk‡ | |||

| Low | 30/1226 | 32/1250 | 0.95 (0.58–1.57) |

| High | 128/2600 | 117/2606 | 1.1 (0.85–1.41) |

| Contraceptive use at screening | |||

| Long term/user independent§ | 11/226 | 6/231 | 1.91 (0.71–5.16) |

| Injectable hormones | 49/898 | 57/945 | 0.91 (0.62–1.34) |

| Pill¶ | 43/1471 | 36/1493 | 1.21 (0.78–1.89) |

| Barrier[| | ](#TFN16) | 36/768 | 35/723 |

| Other/none | 19/472 | 17/475 | 1.14 (0.59–2.20) |

| Condom use in past 3 months at enrolment | |||

| Never | 29/1163 | 41/1145 | 0.74 (0.46–1.19) |

| Sometimes | 75/1541 | 58/1491 | 1.22 (0.87–1.72) |

| Always | 54/1123 | 50/1225 | 1.13 (0.77–1.66) |

Over the course of the study, women in the intervention group reported diaphragm use at last sex 73% of the time (9385 times reported out of 12868 visits). Woman-time corresponding to visits where diaphragm use was reported in the control group was very low (0.15%), and was excluded from per-protocol analyses. The per-protocol relative hazard of HIV incidence was 0.90 (95% CI 0.68–1.17). This result was confirmed with the cumulative measure of diaphragm adherence (always used diaphragms since the last study visit): 0.83 (95% CI 0.61–1.14).

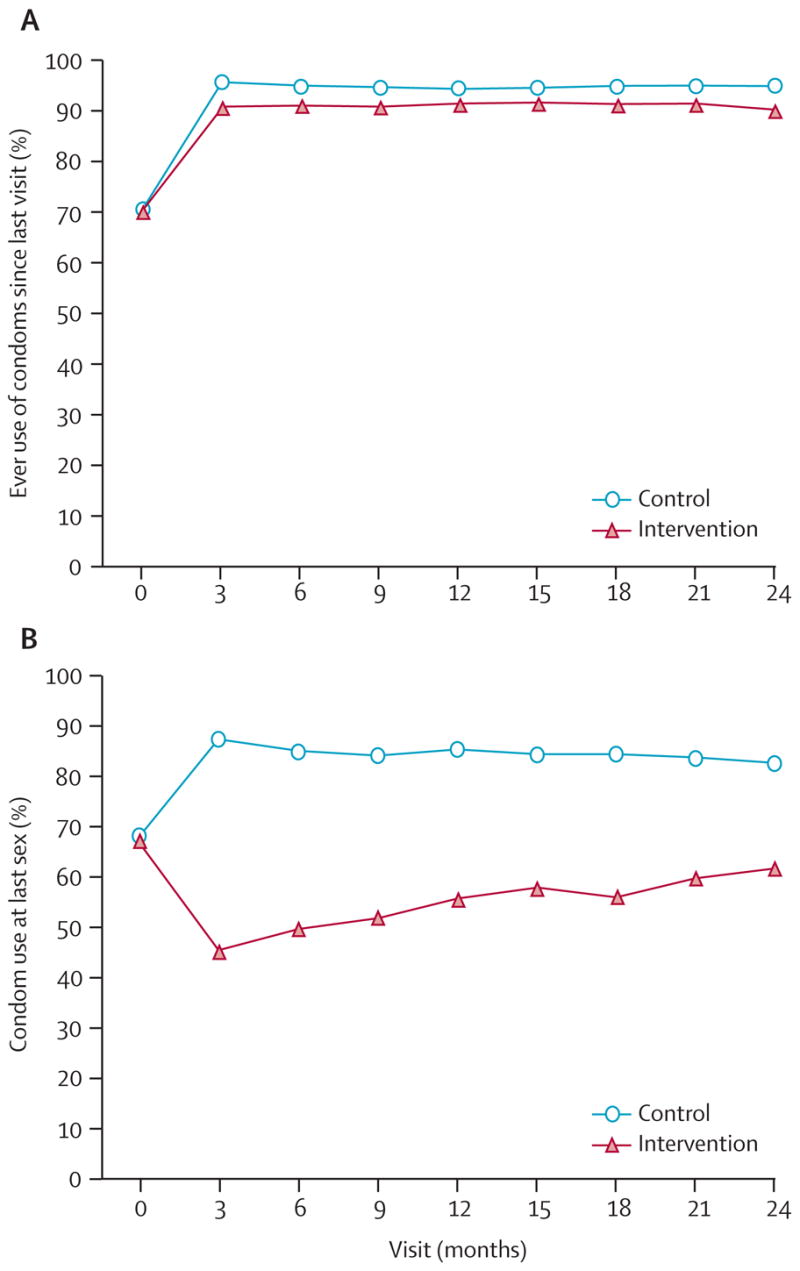

As shown in table 1, reported condom use was similar at enrolment in both groups. After enrolment, the proportion of women who ever used condoms significantly increased (p<0.0001, figure 3). However, this increase was less pronounced among women in the intervention group than in the control group (relative risk 0.96; 95% CI 0.95–0.97). Rates of condom use at last sex diverged after enrolment, with reported use at last sex averaging 53.5% across all visits (95% CI 52.1–54.9) for women in the intervention group, and 85.1% (84.2–86.0) for those in the control group (relative risk 0.62, 95% CI 0.61–0.64; figure 3). Together, these data suggest an increase in overall condom uptake after enrolment regardless of group. However, women in the intervention group reported condom use less often than did those in the control group. Additionally, we observed that in women assigned to the intervention group, the odds of condom use at last sex for those who reported using diaphragms were less than those for women who did not report using diaphragms (odds ratio 0.57, 95% CI 0.51–0.63; p<0.0001; data not shown).

Figure 3. Proportions of women reporting (A) ever using condoms since last visit and (B) condom use at last sex, by visit.

11 women in the intervention group and 12 in the control group died during the study. No serious adverse events were classed as definitely or probably related to use of diaphragm or gel. Three participants in the intervention group reported a serious adverse event that resulted in the permanent discontinuation of product use; one total hysterectomy and two uterine fibroids. The proportions of participants reporting adverse events and serious adverse events, including those related to the reproductive tract, were similar across sites and between groups (table 4). The proportion of women reporting adverse events of bacterial vaginosis, candidosis or laboratory-confirmed urinary tract infection did not differ between the groups. Rates of pregnancy were the same in both groups: the yearly incidence of first pregnancy was 13.1% (477 in 3635 woman-years) in the intervention group and 13.2% (482 in 3656 woman-years) in the control group (hazard ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.88–1.13).

Table 4.

Reported adverse events and serious adverse events, by group

| Adverse events | Serious adverse events | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Overall | ||||

| Number of participants | 2521 | 2518 | 2521 | 2518 |

| Participants with ≥1 event | 1523 (60%) | 1529 (61%) | 130 (5%) | 101 (4%) |

| RT-related | 814 (32%) | 774 (31%) | 17 (1%) | 7 (<1%) |

| Bacterial vaginosis | 131 (5%) | 127 (5%) | 0 | 0 |

| Vaginal candidosis | 87 (3%) | 66 (3%) | 0 | 0 |

| PID | 73 (3%) | 57 (3%) | 2 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other RT-related | 704 (28%) | 664 (26%) | 16 (1%) | 7 (<1%) |

| UT-related | 235 (9%) | 220 (9%) | 2 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| UT infection | 54 (2%) | 49 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 |

| Other UT-related | 196 (8%) | 182 (7%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) |

| Pregnancy-related | 62 (2%) | 46 (2%) | 45 (2%) | 48 (2%) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 11 (<1%) | 12 (<1%) |

| Moderate | ||||

| RT/UT/pregnancy | 511 (20%) | 474 (19%) | 28 (1%) | 29 (1%) |

| Non-RT/UT/pregnancy | 690 (27%) | 688 (27%) | 28 (1%) | 18 (1%) |

| Severe | ||||

| RT/UT/pregnancy | 38 (2%) | 32 (1%) | 32 (1%) | 20 (1%) |

| Non-RT/UT/pregnancy | 75 (3%) | 93 (4%) | 43 (2%) | 32 (1%) |

Discussion

Among women receiving a state-of-the-art HIV prevention package (including risk reduction counselling, voluntary counselling and testing, and diagnosis and treatment of STIs), we observed no added protective benefit of providing the diaphragm and lubricant gel in addition to provision of male condoms. Incidence of HIV in the intervention group was similar to that in the control group of the study. This result held true across all pre-specified subgroups assessed, although this population mainly consisted of women in primary partnerships, and our findings might not be generalisable to other groups exposed to different risks and in other cultures. Thus, although the intervention seemed safe and did not significantly increase the risk of HIV or adverse events, our results do not support the addition of the diaphragm to current strategies to prevent HIV infection.

Overall, the study achieved a high rate of condom use that was maintained over time, indicating that most women could successfully negotiate use of male condoms with their partners. Nevertheless, HIV incidence in the trial remained high, suggesting that self-report might not have been accurate. Contrary to our previous findings40 (although perhaps not surprisingly, since our study was, by necessity, open label) use of diaphragms and use of condoms were not independent. In fact, we noted differential condom use by group across several measures: condom use at last sex act, and the cumulative measure of condom use (both assessed by ACASI), as well as participants’ reported date of last condom use (during in-person interview with clinicians; data not shown). All these measures showed significant differences indicating lower condom use in the intervention group, in spite of intensive counselling offered to participants at every visit to emphasise the unknown efficacy of the diaphragm and the importance of using condoms at every sexual act. These results might imply increased harm resulting from promotion of diaphragms. Importantly, however, lower use of condoms in the intervention group than in controls did not result in an increase in HIV risk, suggesting that diaphragm use might have compensated for the difference in condom use. Of course, uncertainty about self-reported condom use makes other explanations equally plausible. For example, condom use might have been over-reported in the control group, in which case actual rates of condom use might have been similar between the groups, and diaphragms might have had no effect on infection rates.

Identification of the personal, relationship, and contextual factors contributing to the divergence in condom use by study group is an important topic that will be addressed through future quantitative and qualitative analyses. On the basis of preliminary examinations of these data, we postulate that despite our counselling, women might have regarded the diaphragm as a viable alternative to condoms to protect against HIV. Furthermore, some women might not have liked the idea of having two products simultaneously in their vagina. As shown in previous research, we also speculate that some men might have been less inclined to use condoms if they knew their female partner was using a diaphragm.22 Although we know that discreet use of the diaphragm is completely possible and that male partner involvement is not a requirement of using this method, preliminary data from this trial indicate that most women nevertheless chose to disclose diaphragm use to their partner.22,41

Assessment of a user-dependent method of prevention is driven by both efficacy and actual use of the product. We did not quite achieve the rates of diaphragm use projected during the design of the trial and, unlike in studies of directly observed treatment or prevention (eg, circumcision) we had no way to validate adherence reports. Additionally, our study emphasises the challenges of relying on self-reported data for sexual behaviour, and the need to improve measurements and develop objective measures of sexual activity, unprotected sex, and product use. To minimise recall bias, we chose product use at last sex as our primary measure of diaphragm and condom use.39 Additionally, we used ACASI, which has been shown to decrease bias of self-reported sensitive behaviours.42–44

Unfortunately, our results add to the growing body of HIV-prevention trials that have failed to show a protective effect of interventions.45 To date, of 25 randomised controlled trials for HIV prevention, four have shown a protective effect (three trials of circumcision and one trial of treating STIs to prevent HIV), whereas 19 showed no effect and two had potentially a deleterious effect.46–49 Notably, the latter two were among the results of five recently completed or halted microbicide trials where the other three showed no effect.12,14,33 As might have been the case in other studies, high uptake of the prevention package that was offered in our trial, including high reported rates of condom use (albeit differential), might have reduced our ability to detect an independent effect of the intervention. Post-trial simulations showed that in a similarly designed study, with levels of diaphragm and condom use equivalent to that observed in our study sample (70% diaphragm use, 85% condom use in the control group and 50% condom use in the intervention group), the power to detect a 33% intervention-related reduction in incidence would be less than 25%.

More power could perhaps have been attained with a different study design, for example if we started with a diaphragm intervention and then randomised only women who were consistent users (acknowledging that even 80% adherence might be insufficient to detect an effect) or if we excluded those who were able to use condoms consistently after a short run-in. Regardless of these study design issues, as was shown in another similar study,50 the high rates of condom use we observed during the trial cannot be guaranteed to be sustained now that the study is over.

The absence of observed protective effect of the intervention over and above that of condoms in this trial is disappointing. Because animal studies with diaphragms are impractical, interpretation of our results is restricted by a shortage of preclinical data that could have helped to establish whether the diaphragm is efficacious. High uptake of condoms, non-independence of diaphragm and condom use in the intervention group, lower than expected use of the diaphragm, and more general problems of measurement of self-reported behaviours all challenged our ability to detect an effect, if one existed. Solid biological plausibility for the role of the cervix in HIV acquisition remains, and the methodological challenges we faced do not diminish the importance of continued research on cervical barriers—for example, investigation of methods that could be used on a schedule independent from coitus, that are less subject to individual adherence, or that can be used as a vehicle for microbicide delivery.23–26 In future similar trials, researchers should also consider adding a validation of self-reported sexual behaviour with objective biomarkers of condom use and of adherence to the intervention.51 For all prevention methods that are user-dependent, continuing research on ways to increase adherence (and measurement thereof) is as important as the need to develop and test new prevention methods.

Women who cannot convince their male partners to use condoms are still in urgent need of a female-controlled method of protection. In addition to research on methods that are inherently more efficacious, we must develop the instruments to allow assessment of even modest amounts of protection.

Acknowledgments

We would first and foremost like to thank the women who participated in this study. We also thank the administrative and data coordination staff at the University of California, San Francisco; and the entire MIRA study teams at Ibis Reproductive Health; The University of Zimbabwe–University of California, San Francisco Collaborative Research Programme; the Medical Research Council, HIV Prevention Research Unit (Durban); and the Perinatal HIV Research Unit of the University of the Witwatersrand. We thank our Community Advisory Boards at each study site, who provided valuable input before and during the study. The MIRA Trial Technical Advisory Committee had a critical role in advising the investigators on important scientific decisions during the trial. We thank Bernie Lo and Barbara van der Pol for providing invaluable ethical and laboratory consultation, respectively. We would like to acknowledge the time and oversight provided by the members of the MIRA data safety monitoring board and the following institutional review boards: UCSF Committee on Human Research, the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, the Medicines Control Authority of Zimbabwe, Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of the Witwatersrand, and Western Institutional Review Board. Additionally, we acknowledge Tim Farley, Anne Johnson, and Alexandra Minnis for their valuable review and comments on the manuscript. We would like to make a special tribute to the memory of Charlotte Ellertson who provided inspiration and scientific leadership that made this trial possible. The MIRA trial was funded through a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (number 21082).

Footnotes

Contributors

N Padian was the overall principal investigator and provided scientific leadership on study design, implementation, data interpretation, and writing. A van der Straten was the co-principal investigator and provided scientific and management leadership on all aspects of the study, and contributed to and coordinated the analysis and writing committees. G Ramjee, T Chipato, and G deBruyn were the site principal investigators. They supervised study implementation at each research site and contributed to interpretation of data and review of the manuscript. S Shiboski was the lead statistician and contributed to the study analysis and writing. K Blanchard was the principal investigator from Ibis Reproductive Health. K Blanchard, E T Montgomery, and H Fancher participated in the study design, provided management leadership in study operations, reviewed and interpreted study data, and contributed to writing. Additional statistical expertise, analysis, and manuscript revision was also provided by H Cheng, M Rosenblum, M van der Laan, and N Jewell. J McIntyre provided senior scientific input on the interpretation of results, and oversight of study implementation at the Perinatal HIV Research Unit site.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS/WHO. AIDS epidemic update: December 2006. Geneva: UNAIDS/WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. HIV/AIDS epidemiological surveillance report for the WHO African Region: 2005 Update. Harare: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heise LL, Elias C. Transforming aids prevention to meet women’s needs: a focus on developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:931–43. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00165-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.d’Cruz-Grote D. Prevention of HIV infection in developing countries. Lancet. 1996;348:1071–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)11031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Green G, Pool R, Harrison S, et al. Female control of sexuality: illusion or reality? Use of vaginal products in south west Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:585–98. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ulin PR. African women and AIDS: negotiating behavioral change. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:63–73. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdool Q, Karim Barriers to preventing human immunodeficiency virus in women: experiences from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 2001;56:193–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moench T, Chipato T, Padian N. Preventing disease by protecting the cervix: the unexplored promise of internal vaginal barrier devices. AIDS. 2001;15:1595–602. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantell JE, Myer L, Carballo-Dieguez A, et al. Microbicide acceptability research: current approaches and future directions. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:319–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FHI. Joint statement on Savvy phase 3 trial in Ghana to test the effectiveness of Savvy gel in preventing HIV. Durham, NC: FHI; 2005. Press release. [Google Scholar]

- 11.FHI. Phase 3 Trial in Nigeria Evaluating the Effectiveness of SAVVY Gel in Preventing HIV Infection in Women Will Close. Durham, NC: FHI; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anonymous Trial and failure. Nature. 2007;446:1. doi: 10.1038/446001a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Check E. Scientists rethink approach to HIV gels. Nature. 2007;446:12. doi: 10.1038/446012a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.CONRAD. Phase III Trials of cellulose sulfate microbicide for HIV prevention closed. Arlington, VA: CONRAD; 2007. Press release. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bulut A, Ortayli N, Ringheim K, et al. Assessing the acceptability, service delivery requirements, and use-effectiveness of the diaphragm in Colombia, Philippines, and Turkey. Contraception. 2001;63:267–75. doi: 10.1016/s0010-7824(01)00204-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.di Giacomo do Lago T, Babose R, Kalckmann S, Villela W, Gohiman S. Acceptability of the diaphragm among low-income women in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Int Fam Plann Perspect. 1995;21:114–118. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ravindran TKS. A study of user perspectives on the diaphragm in an urban Indian setting. Washington, DC: The Population Council; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behets F, Turner AN, Van Damme K, et al. Acceptability and feasibility of continuous diaphragm use among sex workers in Madagascar. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:472–76. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.015107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Straten A, Kang M, Posner SF, Kamba M, Chipato T, Padian NS. Predictors of diaphragm use as a potential sexually transmitted disease/HIV prevention method in Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:64–71. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000148301.90343.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buck J, Kang M, van der Straten A, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, Posner S, Padian N. Barrier method preferences and perceptions among Zimbabwean women and their partners. AIDS Behav. 2005;9:415–22. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van der Straten A, Kang M, Buck J, et al. Partner involvement in female-controlled method use: experience with the diaphragm in Zimbabwe. Int Conf AIDS. 2004 Jul 11–16; (abstr ThOrC1376) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang M-S, Buck J, Padian N, Posner SF, Khumalo-Sakutukwa G, van der Straten A. The importance of discreet use of the diaphragm to Zimbabwean women and their partners. AIDS Behav. 2007;11:443–51. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levine WC, Pope V, Bhoomkar A, et al. Increase in endocervical CD4 lymphocytes among women with nonulcerative sexually transmitted diseases. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:167–74. doi: 10.1086/513820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, He T, Talal A, Wang G, Frankel SS, Ho DD. In vivo distribution of the human immunodeficiency virus/simian immunodeficiency virus coreceptors: CXCR4, CCR3, and CCR5. J Virol. 1998;72:5035–45. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.5035-5045.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patterson BK, Landay A, Andersson J, et al. Repertoire of chemokine receptor expression in the female genital tract: implications for human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:481–90. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65591-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hussain LA, Lehner T. Comparative investigation of Langerhans’ cells and potential receptors for HIV in oral, genitourinary and rectal epithelia. Immunology. 1995;85:475–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pudney J, Quayle AJ, Anderson DJ. Immunological microenvironments in the human vagina and cervix: mediators of cellular immunity are concentrated in the cervical transformation zone. Biol Reprod. 2005;73:1253–63. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.043133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bounds W, Guillebaud J, Dominik R, Dalberth BT. The diaphragm with and without spermicide. A randomized, comparative efficacy trial. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:764–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trussell J. Contraceptive efficacy. In: Hatcher R, Trussell J, Nelson A, Cates W Jr, Stewart F, Kowal D, editors. Contraceptive technology. 18. New York: Ardent Media; 2004. pp. 773–845. [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Laak JA, de Bie LM, de Leeuw H, de Wilde PC, Hanselaar AG. The effect of Replens on vaginal cytology in the treatment of postmenopausal atrophy: cytomorphology versus computerised cytometry. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55:446–51. doi: 10.1136/jcp.55.6.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Damme L, Niruthisard S, Atisook R, et al. Safety evaluation of nonoxynol-9 gel in women at low risk of HIV infection. AIDS. 1998;12:433–37. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199804000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Damme L, Chandeying V, Ramjee G, et al. Safety of multiple daily applications of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, among female sex workers. COL-1492 Phase II Study Group. AIDS. 2000;14:85–88. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001070-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Damme L, Ramjee G, Alary M, et al. Effectiveness of COL-1492, a nonoxynol-9 vaginal gel, on HIV-1 transmission in female sex workers: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:971–77. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maguire RA, Bergman N, Phillips DM. Comparison of microbicides for efficacy in protecting mice against vaginal challenge with herpes simplex virus type 2, cytotoxicity, antibacterial properties, and sperm immobilization. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:259–65. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200105000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen D, Lee H, Poast J, Cloyd MW, Baron S. Preventing sexual transmission of HIV: anti-HIV bioregulatory and homeostatic components of commercial sexual lubricants. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2004;18:268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohan LC, Ratner D, McCullough K, Hiller SL, Gupta P. Measurement of anti-HIV activity of marketed vaginal products and excipients using a PBMC-based in vitro assay. Sex Transm Dis. 2004;31:143–48. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000114655.79109.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lan K, DeMets D. Discrete sequential boundaries for clinical trials. Biometrika. 1983;70:659–63. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Brien PC, Fleming TR. A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics. 1979;35:549–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anderson J, Rietmeijer C, Wilson R. Asking about condom use: is there a standard approach that should be adopted across surveys? St. Louis: Annual meeting of the American Statistical Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Posner SF, van der Straten A, Kang MS, Padian N, Chipato T. Introducing diaphragms into the mix: what happens to male condom use patterns? AIDS Behav. 2005;9:443–49. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9016-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Straten A, Lee M, Montgomery E, et al. Characteristics of non-disclosers of diaphragm use among Southern African women enrolled in a HIV prevention trial (abstr MP-099). 16th Biennial Meeting of the International Society for Sexually Transmitted Diseases Research; Amsterdam. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mensch B, Hewett P, Gregory R. Sexual behavior and STI/HIV status among adolescents in rural Malawi: an evaluation of the effect of interview mode on reporting. Los Angeles, CA: Population Association of America Annual Meeting; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minnis AM, Muchini A, Shiboski S, et al. Audio computer-assisted self-interviewing in reproductive health research: reliability assessment among women in Harare, Zimbabwe. Contraception. 2007;75:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner C, Ku L, Rogers S. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–73. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wasserheit JN. The STD-HIV connection from research to action: are we lost in translation?; 14th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Los Angeles. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Grosskurth H, Mosha F, Todd J, et al. Impact of improved treatment of sexually transmitted diseases on HIV infection in rural Tanzania: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1995;346:530–36. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:643–56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369:657–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong EL, Roddy RE, Tucker H, Tamoufe U, Ryan K, Ngampoua F. Use of male condoms during and after randomized, controlled trial participation in Cameroon. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:300–07. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000162362.98248.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gallo MF, Behets FM, Steiner MJ, et al. Prostate-specific antigen to ascertain reliability of self-reported coital exposure to semen. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:476–79. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000231960.92850.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]