Phage SPP1 Reversible Adsorption to Bacillus subtilis Cell Wall Teichoic Acids Accelerates Virus Recognition of Membrane Receptor YueB (original) (raw)

Abstract

Bacteriophage SPP1 targets the host cell membrane protein YueB to irreversibly adsorb and infect Bacillus subtilis. Interestingly, SPP1 still binds to the surface of yueB mutants, although in a completely reversible way. We evaluated here the relevance of a reversible step in SPP1 adsorption and identified the receptor(s) involved. We show that reversible adsorption is impaired in B. subtilis mutants defective in the glucosylation pathway of teichoic acids or displaying a modified chemical composition of these polymers. The results indicate that glucosylated poly(glycerolphosphate) cell wall teichoic acid is the major target for SPP1 reversible binding. Interaction with this polymer is characterized by a fast adsorption rate showing low-temperature dependence, followed by a rapid establishment of an equilibrium state between adsorbed and free phages. This equilibrium is basically determined by the rate of phage dissociation, which exhibits a strong dependence on temperature compatible with an Arrhenius law. This allowed us to determine an activation energy of 22.6 kcal/mol for phage release. Finally, we show that SPP1 reversible interaction strongly accelerates irreversible binding to YueB. Our results support a model in which fast SPP1 adsorption to and desorption from teichoic acids allows SPP1 to scan the bacterial surface for rapid YueB recognition.

The supramolecular structure of phage particles is designed to protect the viral genome from the environment and to mediate its efficient delivery to bacterial host cells. Phage infection is initiated by the specific interaction between virion proteins and receptors of the bacterial surface, a process classically known as adsorption. The majority of studied phages employ a tail structure to recognize cellular receptors. Under appropriate conditions, this tail-receptor interaction induces structural rearrangements of the tail that ultimately are transmitted to the head-tail connector, triggering its opening for phage DNA release (20, 27, 32).

Early studies indicated that phage adsorption involves reversible and irreversible interactions with host receptors. Reversibly adsorbed phages can be released from cells as infectious particles by dilution, whereas irreversibly bound phages are not recoverable as they become committed to infection (2). Reversible and irreversible interactions can occur with the same receptor (24) or, more frequently, involve different surface components (40).

The nature of receptors and their interaction with tail components has been well characterized at the molecular level for a few tailed phages such as λ, T4, T5, T7, and P22 (for a review, see reference 40). However, a complete integrated view of molecular and adsorption kinetics data is lacking in most cases. This is particularly true for phages infecting gram-positive bacteria where current knowledge on the adsorption process hardly extends beyond the identification of a few phage receptor-binding proteins and cellular receptors.

Work on phage adsorption to gram-positive bacteria has highlighted the role of cell wall teichoic acid (WTA), lipoteichoic acid (LTA), and peptidoglycan-associated sugars as phage receptors (40). Frequently, the receptor activity of teichoic acids has been shown to depend on the level of α-glucose and d-alanyl substitution of their poly(glycerolphosphate)[poly(Gro-P)] backbone (8, 9, 29, 43). Mutations affecting the pathway of poly(Gro-P) glucosylation have been associated with B. subtilis resistance to several phages such as φ25, φ29, and SP01 (42, 43).

Recently, important advances have been made on the initial steps underlying phage SPP1 DNA entry into B. subtilis cells. Phage SPP1 requires the presence of the membrane receptor YueB for irreversible adsorption to and infection of its host (35). A purified extracellular domain of YueB was shown to form fiber-like dimers, which are long enough to span the bacterial cell envelope and sufficient to trigger SPP1 DNA ejection in vitro (36). This in vitro system was explored to study the molecular mechanism of transmission of the DNA ejection signal from the tail tip to the head-to-tail connector (27), to demonstrate that there is a limiting step that imposes an energy barrier to the triggering of DNA ejection (30), and to show that DNA repulsion forces stored in the viral capsid must power the ejection of an initial fraction of the SPP1 chromosome into B. subtilis (37).

The goal of the present study was to identify the cellular receptors involved in the SPP1 reversible interaction with the B. subtilis surface and to understand its impact in the whole process of SPP1 adsorption. We show that glucosylated WTAs are the primary receptors for a reversible adsorption step that precedes binding to YueB. Our adsorption kinetics studies demonstrate that reversible interaction with these polymers is critical for the efficient recognition of receptor YueB. This study provides the first complete view of the adsorption process of a Siphoviridae phage to the surface of a gram-positive bacterium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria, phages, plasmids, and growth conditions.

B. subtilis strains, phages and plasmids used in the present study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli MC1061 [araD139 Δ(ara leu)7697 Δ_lacX74 galU galK hsdR2 strA mcrA mcrB1_] (6) was used as the primary host for the selection of plasmid constructs. E. coli, B. subtilis, and phage were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (33) as described by São-José et al. (35). Plasmid-carrying E. coli strains were cultured in the presence of ampicillin (100 μg/ml. Erythromycin (0.5 μg/ml), kanamycin (7.5 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (5 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (100 μg/ml) were used to select B. subtilis transformants. B. subtilis transformants expressing β-galactosidase were selected on X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside)-supplemented (0.02% [wt/vol]) LB plates. B. subtilis integrants in tagE were grown in the presence of 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) to prevent transcriptional polar effects. B. subtilis gtaC, gtaB, tagE, and ypfP mutant strains were grown in the presence of 1 mM MgCl2 (21). Phages were maintained and diluted in TBT buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgSO4; pH 7.5).

TABLE 1.

B. subtilis strains, phages, and plasmids used in this study

| B. subtilis strains, phages, or plasmids | Genotype and/or relevant featuresa | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| B. subtilis strains | ||

| L16601 | B. subtilis 168; SPP1 indicator strain | 22 |

| L5703 | 168/W23 interstrain hybrid | 18 |

| CSJ1 | L16601 derivative resistant to SPP1; Δ_yueB_ | 35 |

| CSJ3 | L16601 derivative overexpressing yueB, Eryr | 35 |

| L16131 | _gtaC_ΩpBS640; Cmr | V. Lazarevic, unpublished data |

| L16114 | _gtaB_Ωp624; Cmr | 21 |

| KP261 | Δ_ypfP_; Kanr | 28 |

| CSJ1_gtaC_ | CSJ1 derivative; _gtaC_ΩpBS640; Cmr | This study |

| CSJ1_gtaB_ | CSJ1 derivative; _gtaB_Ωp624; Cmr | This study |

| CSJ1_ypfP_ | CSJ1 derivative; Δ_ypfP_; Kanr | This study |

| CSJ1_tagE_ | CSJ1 derivative; _tagE_ΩpCBM30; Eryr | This study |

| CSJ1_tagE/ypfP_ | CSJ1 derivative; tagE_ΩpCBM30 Δ_ypfP; Eryr Kanr | This study |

| L16601_gtaC_ | L16601 derivative; _gtaC_ΩpBS640; Cmr | This study |

| L16601_gtaB_ | L16601 derivative; _gtaB_Ωp624; Cmr | This study |

| L16601_ypfP_ | L16601 derivative; Δ_ypfP_; Kanr | This study |

| L16601_tagE_ | L16601 derivative; _tagE_ΩpCBM30; Eryr | This study |

| L16601_tagE/ypfP_ | L16601 derivative; tagE_ΩpCBM30 Δ_ypfP; Eryr Kanr | This study |

| CSJ3_gtaC_ | CSJ3 derivative; _gtaC_ΩpBS640; Eryr Cmr | This study |

| B. subtilis phages | ||

| SPP1 | Lytic phage | 31 |

| SP01 | Lytic phage; used to control transfer of cell wall mutations | 26 |

| Vectors and plasmids | ||

| pMutin-4 | Integration vector used for gene inactivation; Ampr, Eryr | 39 |

| pCBM30 | pMutin-4 derivative carrying a PCR product internal to tagE | This study |

General recombinant-DNA techniques.

Extraction of B. subtilis genomic DNA and E. coli plasmid DNA, DNA amplification by PCR, and purification of PCR products was as reported in São José et al. (35). Restriction endonuclease digestions, DNA ligations, and conventional agarose gel electrophoresis were carried out essentially as described by Sambrook and Russell (33). Transformation of E. coli and B. subtilis strains with recombinant plasmids was performed according to the methods of Chung et al. (7) and Yasbin et al. (41), respectively.

Construction of B. subtilis mutants.

To construct a B. subtilis tagE knockout mutant, an internal region of tagE was amplified from the genome of the wild-type strain L16601 using the primers tagE-1 and tagE-2 (5′-TTGGAATTCCATGCGGTGAGTGAATCTAATAT-3′ and 5′-TTTGGATCCGTCAAGGCCTATCCTTTCTTC-3′, respectively). The PCR product was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, cloned into similarly digested pMutin-4, and the recombinant plasmid, pCBM30, was recovered in E. coli strain MC1061. This plasmid was used to transform B. subtilis strains L16601 and CSJ1, and the integrants were selected for erythromycin resistance and β-galactosidase activity on LB plates supplemented with X-Gal and IPTG. Resistance to phage SPO1 was used to confirm the disruption of tagE (42).

Transfer of mutations gtaC, gtaB, and ypfP from strains L16131, L16114, and KP261, respectively, to strains L16601, CSJ1, and CSJ3 was performed by transforming the recipient strains with donor chromosomal DNA. The mutations corresponded to gene disruptions after plasmid integration (gtaB and gtaC) and to gene replacement by an antibiotic resistance cassette (ypfP). Transformants were selected for resistance markers, and mutations were confirmed by PCR and by the SP01 resistance phenotype (in the case of gta mutations [42]).

Measurement of SPP1 adsorption.

SPP1 total adsorption was measured at defined times of cell/phage contact by titrating free phages present in the supernatant (PFU/ml) after centrifugation. In all adsorption assays B. subtilis cells were collected from exponentially growing cultures (_A_600 = 0.8, about 108 CFU/ml), adjusted to different cellular densities in LB medium (_A_600 values ranging from 0.4 to 16), and supplemented with 15 mM CaCl2 and 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml before phage addition. Chloramphenicol ensured the arrest of cell growth and phage development. After the cells were equilibrated for 10 min at different temperatures (from 0 to 37°C) ∼107 PFU of SPP1/ml was added. Control mixtures without added cells were used to confirm the phage input in each experiment.

The initial rate of reversible adsorption (_R_ads) to strain CSJ1 was calculated using the formula _R_ads = ln(P_0/P)/Δ_t, where P_0 is the phage input and P is the fraction of free phages after a Δ_t period. The adsorption rate constant (_k_1) is the ratio between _R_ads and the bacterial cell mass, here expressed as _A_600 (0.8 in these experiments).

SPP1 reversible adsorption was also quantitatively studied by determining the fraction of free phages at the equilibrium state (40, 50, and 60 min after phage addition unless stated otherwise). The data allowed the calculation of the equilibrium constant: _K_eq = _k_1/_k_2 = (_P_0 − P)/(_P_·_A_600), with _P_0, P, and _A_600 as described above. Unless otherwise indicated, in assays with B. subtilis cell wall mutants the value of _K_eq was determined with cultures adjusted to at least three different _A_600 values (ranging from 0.4 to 16), with the lowest ensuring a minimum of 50% of SPP1 adsorption. The dissociation rate constant (_k_2) was determined using the experimental values for _K_eq and _k_1 and the formula _K_eq = _k_1/_k_2.

SPP1 irreversible adsorption to B. subtilis set at an _A_600 of 0.8 or 1.6 was measured by enumerating free phages after performing a 100-fold dilution of bacteria/phage mixtures (see reference 35 for details). The irreversible adsorption constant _k_ads was calculated as the ratio between the irreversible adsorption rate and the bacterial cell mass: _k_ads = ln(_P_0/P)/(Δ_t_·_A_600), with P_0, P, Δ_t, and _A_600 as described above.

ConA and α-MG competition assays.

Concanavalin A (ConA) and α-methyl-glucoside (α-MG) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. CSJ1 cells were concentrated to _A_600 of 1.6 in TBT buffer supplemented with 0.01% gelatin, 0.5 mg of ConA/ml, 15 mM CaCl2, and 50 μg of chloramphenicol/ml. The presence of gelatin ensured phage stability during agitation. After 10 min at 37°C, SPP1 was added, and the samples were placed on a rotating wheel with gentle agitation at room temperature (∼24.5°C). Reversible adsorption was evaluated by determining the fraction of free phages at equilibrium. At 60 min after phage addition, 25 mM α-MG was added, and the fraction of free phages was determined at 75, 90, and 105 min. A control sample contained ConA dilution buffer (10 mM Tris, 10 mM MgCl2; pH 7) instead of ConA. Phage input was controlled as described above.

RESULTS

Kinetics of SPP1 reversible adsorption to yueB mutant cells.

Initially, we studied SPP1 adsorption to B. subtilis cells that do not synthesize the YueB receptor. Cells of the wild-type strain L16601 and of the SPP1 resistant mutant CSJ1, which carries an extensive deletion of yueB (35), were pre-equilibrated at 0°C and challenged for SPP1 total adsorption. Total adsorption refers to the sum of phages adsorbed reversibly and irreversibly. At 20 min after phage addition at 0°C, 99% of the added virus particles (as PFU) had bound to each strain with similar rates of adsorption (1% of free phages, Fig. 1). The fraction of adsorbed phages remained unchanged for an additional period of 20 min, indicating that equilibrium between adsorbed and free phages had been reached.

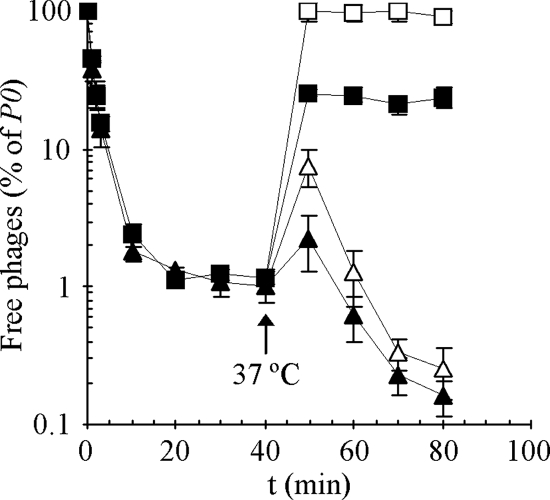

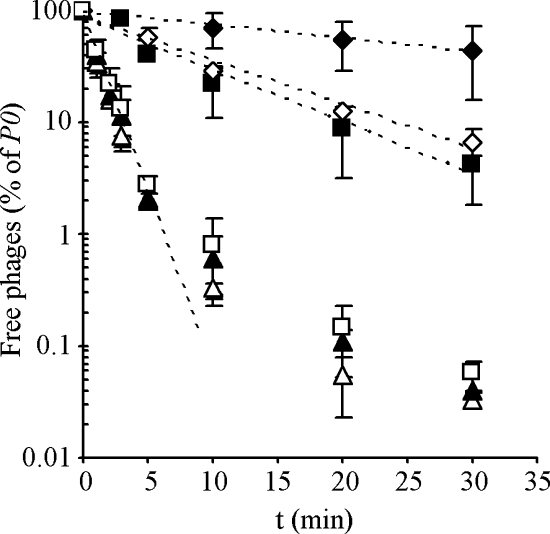

FIG. 1.

SPP1 adsorption to wild-type (L16601, triangles) and yueB (CSJ1, squares) strains. Cultures of both strains were adjusted to an _A_600 of 1.6 and equilibrated at 0°C. SPP1 was then added to each culture, and the phage total adsorption was measured during a period of 40 min. At this point (arrow) mixtures were transferred to 37°C, and both total (solid symbols) and irreversible adsorption (open symbols) were evaluated for an additional period of 40 min. Free phages are represented as a normalized concentration (P × 100)/_P_0, where P is the titer of free phages (in PFU/ml) at time t and _P_0 is the initial input. The plotted values correspond to the average from three independent experiments. Standard deviation bars are shown.

The mixtures were then shifted to 37°C and scored for total and irreversible adsorption (filled and open symbols in Fig. 1, respectively). We evaluated irreversible adsorption by diluting samples 100-fold prior to centrifugation, a procedure that releases reversibly adsorbed phages (2). By 10 min after the temperature shift, phages had been released from both strains. However, whereas SPP1 efficiently re-adsorbed to the wild-type strain with incubation at 37°C, it failed to re-adsorb to strain CSJ1 to the level observed at 0°C; the total fraction of phages adsorbed to strain CSJ1 stabilized ca. 80% (Fig. 1). Moreover, these adsorbed phages were only bound reversibly since dilution and centrifugation allowed complete recovery of the initial phage input. Dilution of CSJ1/SPP1 complexes maintained at 0°C gave the same results, provided enough time was allowed for phage release (data not shown). Note that continuous incubation of SPP1 with the wild type at 37°C resulted in higher levels of both total and irreversible adsorption compared to total adsorption at 0°C. This most probably results from the fact that at the lower temperature the contribution of irreversible binding to total adsorption is much reduced (see below).

Overall, the results presented above indicated that SPP1 adsorbs reversibly (but not irreversibly) to a yueB strain, apparently with the same efficiency as that observed for the wild type. The existence of a reversible step in SPP1 adsorption was confirmed by studying the kinetics of total and irreversible adsorption to the wild type at 37°C. Under these conditions the SPP1 total adsorption is very fast, with <1% free phages recovered from the supernatant after 5 min of incubation. At all times the total adsorption was higher than irreversible adsorption, indicating the presence of reversibly adsorbed phages (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

Effect of temperature on reversible SPP1 adsorption: phage release follows Arrhenius kinetics.

In a wild-type strain the phenomenon of phage adsorption is typically described by the following equation:

|

(1) |

|---|

where P, B, PB, and PB* represent free phages, free bacteria, reversible phage-bacterium complexes, and irreversible phage-bacterium complexes, respectively, and _k_1, _k_2, and _k_3 indicate the reversible adsorption rate constant, the dissociation rate constant, and the irreversible adsorption rate constant, respectively. For strain CSJ1, to which SPP1 is unable to adsorb irreversibly, the adsorption process is simplified to:

|

(2) |

|---|

where a specific equilibrium between the fraction of free and adsorbed phages depends on the relative contributions of _k_1 and _k_2.

The results presented above (Fig. 1) suggested that the release of reversibly adsorbed SPP1 virus particles is a temperature (T)-dependent process, where high temperatures favor phage dissociation (k2) from the cells. To test this hypothesis, we measured the fraction of unbound phages at different temperatures, after the equilibrium state with strain CSJ1 was reached. We observed that in fact the fraction of unadsorbed phages increased exponentially with T (Fig. 2A). As shown below, the increment of free phages with T could not be attributed to a negative effect of the high temperature on the adsorption rate constant (_k_1).

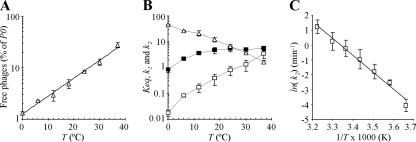

FIG. 2.

Effect of temperature on SPP1 reversible adsorption to strain CSJ1. (A) A CSJ1 culture was adjusted to an _A_600 of 1.6, and samples were equilibrated at 0, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 37°C before phage addition. For each temperature the fraction of free phages in the equilibrium state was measured (plotted values as in Fig. 1). (B) Variation of the equilibrium [_K_eq (_A_600−1), ▵], adsorption [_k_1 (min−1 _A_600−1), ▪], and dissociation [_k_2 (min−1), □] constants with temperature (averaged values from at least three independent measurements with indication of standard deviation). (C) Arrhenius plot describing the variation of ln(_k_2) as a function of the inverse of T. Error bars are represented.

The equilibrium constant (_K_eq), which provides a measure of the number of phage-bacterium complexes and therefore of the relative contribution of _k_1 and _k_2 (expression 2), is determined by:

|

(3) |

|---|

where _P_0 is the initial phage input, P is the fraction of free phages at the equilibrium state, and _A_600 is the cellular mass. Equation 3 shows that increasing the fraction of adsorbed phages (low P values) results in higher _K_eq values.

To gain more quantitative insight into the effect of temperature on SPP1 adsorption we determined the _K_eq and _k_1 values over a range of temperatures. Reversible adsorption of SPP1 to CSJ1 is characterized by a fast loss of free particles after phage addition and by the rapid establishment of equilibrium (not shown). We thus took the adsorption rate, calculated at the shortest time possible, to estimate _k_1 at different temperatures (see Materials and Methods).

For T ≥ 18°C, _k_1 increased moderately with T, leveling out at 4.6 to 5.6 min−1 _A_600−1 (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, _K_eq showed a sharp decrease with T (Fig. 2B), in agreement with the temperature-dependent increment of free phages shown in Fig. 2A. Using equation 3 and the experimentally obtained values of _K_eq and _k_1 shows that the dissociation rate constant _k_2 increases essentially exponentially with T (Fig. 2B). Thus, temperature has a major impact on the desorption rate of SPP1 from B. subtilis (_k_2 increases 200-fold from 0 to 37°C), and a much less pronounced effect on the adsorption rate constant (an average sixfold increase of _k_1 at temperatures of ≥18°C compared to 0°C).

Figure 2C shows that ln(_k_2) varies linearly with the inverse of T (T in degrees Kelvin). The temperature dependence of the dissociation rate constant is therefore consistent with the Arrhenius law ln(K) = −_E_a/_R_·1/T + log(A), where _E_a is the activation energy, R is the gas constant [8.314472(15) J·K−1·mol−1], and A the pre-exponential factor. From the slope of the curve (= −_E_a/R), we calculated an activation energy for phage SPP1 release of 94.59 kJ/mol (22.6 kcal/mol).

Mutations impairing glucosylation of WTA and LTA lipid anchor affect SPP1 reversible adsorption.

We then sought to determine whether a specific component of the B. subtilis cell surface was involved in SPP1 reversible adsorption. The phage receptor activity of the cell envelope of gram-positive bacteria has been shown to depend on the presence and modification of different cell wall polymers. The nucleotide sugar UDP-Glucose (UDP-Glc) is a precursor in biosynthesis of some of these polymers in B. subtilis (Fig. 3A). UDP-Glc is a substrate of glucosyltranferases (TagE, YpfP, and glucosyltransferases from the gga and eps operons), which transfer glucosyl groups from UDP-Glc to constituents of the major cell WTA, minor WTA, and LTA and to an exopolysaccharide involved in biofilm formation (5, 11, 17, 19, 21, 23). Mutations impairing the synthesis of UDP-Glc, like those affecting α-phosphoglucomutase and UTP:α-glucose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase (gtaC and gtaB) (21, 38), have pleiotropic effects by changing the composition of different cell wall polymers.

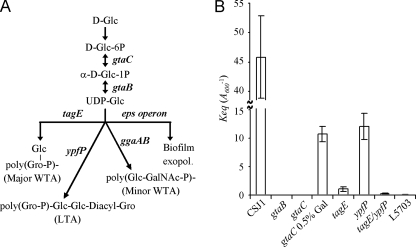

FIG. 3.

Effect of cell wall mutations in SPP1 reversible adsorption. (A) Schematic representation of the pathway of UDP-glucose as a precursor for the synthesis and modification of the major B. subtilis cell wall polymers. Relevant genes involved in the different biosynthetic steps are depicted in boldface. The linkage unit of major and minor WTA is ManNAc-GlcNAc-P. ManNAc, _N_-acetylmannosamine; GalNAc, _N_-acetylgalactosamine. (B) _K_eq values measured in CSJ1 derivative strains carrying mutations in some of the genes shown in panel A. L5703 is an interstrain hybrid producing glucosylated poly(ribitolphosphate) WTA of strain W23 and LTA of strain 168. _K_eq values are the average of at least three measurements using cultures set to different _A_600 values and pre-equilibrated at 0°C before phage addition. Results for CSJ1 (_A_600 = 0.4, 0.6, and 0.8), gtaB and gtaC (_A_600 = 16), gtaC grown in the presence of 0.5% galactose (_A_600 = 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2), tagE (_A_600 = 3.2, 6.4, and 8), ypfP (_A_600 = 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2), tagE/ypfP (_A_600 = 8 and 16), and L5803 (_A_600 = 16) are shown. Error bars are represented.

We took advantage of the finding that maintenance of SPP1/CSJ1 complexes is favored at low temperatures to search for potential B. subtilis cell wall polymers (and their substituents) involved in SPP1 reversible adsorption. To that end, we determined the _K_eq value at 0°C for CSJ1 derivatives affected in some of the biosynthetic steps shown in Fig. 3. No significant changes in cell growth rate or cell morphology were observed between cell wall mutants and the parental CSJ1 (data not shown), provided that required additives were supplied. Specifically, gta and ypfP mutants were grown in the presence of Mg2+ to prevent abnormal cell morphologies (21), whereas the tagE mutant was cultured in the presence of IPTG to ensure the transcription of tagF, an essential gene located immediately downstream of tagE. None of these additives affected SPP1 adsorption to CSJ1 or to the wild type (not shown).

Mutations impairing the synthesis of UDP-Glc (gtaC and gtaB) had a drastic effect on SPP1 reversible adsorption. We were not able to detect the presence of phage-bacterium complexes with these mutants, even at an _A_600 of 16 (we considered significant only averaged adsorption values of ≥50%). Under these conditions the _K_eq for gta mutants was thus considered zero. For the parental CSJ1, _K_eq was 45.8 ± 7 _A_600−1; the gtaC adsorption defect could be partially alleviated by growth in 0.5% galactose, when _K_eq = 10.7 ± 1.4 _A_600−1. A similar result was found for the adsorption of phage φ25 to gtaC mutants (4).

Therefore, UDP-Glc seems to be an essential precursor for the synthesis of a cell wall polymer acting as the receptor for SPP1 reversible adsorption. We have shown previously that ggaAB mutations have no effect on SPP1 adsorption (34). Similarly, the _K_eq values measured in eps deletion mutants did not differ significantly from that calculated in the parental CSJ1 (C. Baptista, unpublished data), indicating that the exopolysaccharide encoded by the eps operon does not participate in SPP1 adsorption.

In contrast, the _K_eq (1.1 ± 0.2 _A_600−1) calculated for the tagE mutant (carrying nonglucosylated WTA) showed a 42-fold decrease compared to that of strain CSJ1. The ypfP mutation, which changes the composition of the LTA lipid anchor, also resulted in a decrease of bound phages (_K_eq = 12.1 ± 2.3 _A_600−1); however, the decrease was much less pronounced than in the case of tagE. Adsorption of SPP1 was almost abolished in a tagE/ypfP double mutant strain (_K_eq = 0.3 ± 0.1 _A_600−1). Interestingly, an extremely low level of adsorption (_K_eq = 0.06 ± 0.1 _A_600−1) was also found with strain L5703, a B. subtilis 168 derivative in which the tag operon is replaced by the tar operon of strain W23 (18, 44). This strain produces the glucosylated poly(ribitolphosphate) WTA of strain W23 and the LTA of strain 168.

Targeting of glucosyl residues with ConA inhibits SPP1 reversible adsorption.

The lectin ConA interacts specifically and reversibly with α-d-glucosyl residues of the poly(Gro-P) backbone of B. subtilis teichoic acids (10). Preincubation of cell walls with ConA inhibited the adsorption of phage φ25 (4), a finding in agreement with the previously reported effect of glucosyl substitution in the φ25 receptor (43).

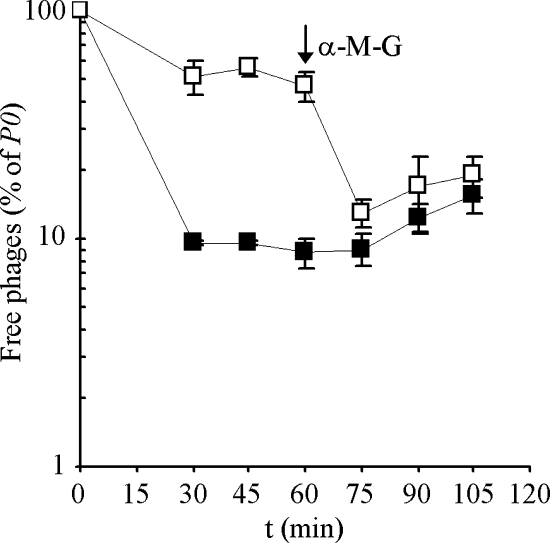

We observed a similar ConA-dependent inhibition of SPP1 reversible adsorption to B. subtilis strain CSJ1 (Fig. 4). ConA-treated CSJ1 cells showed a marked decrease in SPP1 adsorption, with a _K_eq value measured ∼9-fold lower than for the control without ConA. The addition of α-MG, which has high affinity to ConA, dissociated the ConA-cell wall complexes and restored CSJ1 adsorption capacity to levels comparable to those of ConA-untreated cells. After the addition of α-MG a reproducible, slow increase in the fraction of free phages was found both in ConA-treated and in untreated cells. This phenomenon might be explained if α-MG competes with glucosyl residues of the cell wall for binding to SPP1.

FIG. 4.

Effect of ConA on SPP1 reversible adsorption to CSJ1 cells. Strain CSJ1 was concentrated to an _A_600 of 1.6 and incubated at 37°C for 10 min in the presence of ConA (□) or ConA dilution buffer (▪). SPP1 was then added, the mixtures were placed on a rotating wheel at room temperature, and the fraction of free phages in equilibrium was determined. The arrow indicates the time of addition of α-MG. The plotted values correspond to the average of three independent experiments. Standard deviation bars are shown.

Impact of reversible adsorption in SPP1 irreversible binding and infection.

As noted above, we could study SPP1 reversible adsorption without interference of irreversible binding by using a yueB mutant strain (CSJ1). In order to elucidate the role of a reversible interaction in SPP1 irreversible binding to YueB, we studied the effect of cell wall mutations in a wild-type yueB background (L16601). We note that none of the mutations tested affected the level of YueB production, as judged by Western blot analysis (not shown).

The gtaC mutation, which eliminated SPP1 reversible adsorption (see above), drastically slowed down the rate of irreversible binding compared to the wild type (Fig. 5). Similar results were obtained with the gtaB mutant (data not shown). The initial rate of irreversible adsorption to the wild-type and mutant strains (see exponential fitting curves in Fig. 5) was used to calculate the irreversible adsorption constant (_k_ads), which integrates the contributions of _k_1, _k_2, and _k_3. The _k_ads for the gtaC mutant (0.03 ± 0.11 min−1 _A_600−1) was ∼30-fold lower than for the wild type (1.07 ± 0.10 min−1 _A_600−1). The tagE mutation caused also a significant reduction of _k_ads, exhibiting an eightfold decrease compared to the wild type.

FIG. 5.

SPP1 irreversible adsorption to B. subtilis cell wall mutants. Cultures of the wild-type strain L16601 (▵) and of its derivatives carrying mutations gtaC (⧫), tagE (▪), ypfP (▴), and tagE/ypfP (⋄) were grown to an A_600 of 0.8 and equilibrated at 37°C before phage addition. A culture of strain CSJ3_gtaC (□), which is also an L16601 derivative carrying the gtaC mutation but overexpressing YueB, was equally treated. The curves fitting the initial exponential decay of free phages (dashed lines) were used to calculate irreversible adsorption constants (k_ads). For clarity, a single fitting curve is represented of the data for L16601, L16601_ypfP, and CSJ3_gtaC_. The plotted values are the average of at least three independent measurements with standard deviation indicated.

With respect to ypfP deficiency, its comparatively small negative effect on reversible adsorption (see above) did not translate into a significant decrease of SPP1 irreversible adsorption (_k_ads = 0.91 ± 0.16 min−1 _A_600−1). Accordingly, we also observed that the _k_ads for the double-mutant strain tagE/ypfP was close to that of tagE.

Interestingly, when the gtaC mutation was tested in a _yueB_-overexpressing background (CSJ3 background, 35), the SPP1 irreversible adsorption rate almost reached wild-type levels as result of a 25-fold increase of _k_ads, relative to that of L16601 gtaC (Fig. 5). This result suggests that a deficiency in reversible adsorption can be compensated for by increasing the surface concentration of YueB.

The cell wall mutations affecting reversible adsorption allowed SPP1 infection in solid medium. However, they produced a distinct impact in the efficiency of plating and plaque morphology that could be correlated with their relative effect on irreversible adsorption (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material).

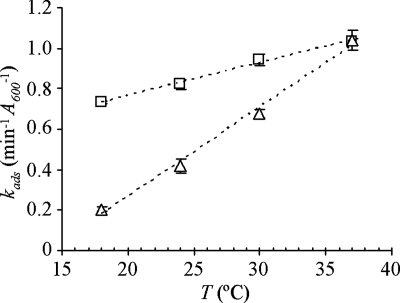

Fast SPP1 dissociation from reversible receptors allows rapid YueB recognition.

We showed above that temperature has a great impact in the dissociation rate of SPP1 from reversible receptors, with k_2 increasing exponentially with T. Based on the expression (1), high temperatures would likely decrease the rate of irreversible binding by shifting the equilibrium toward free phages. We studied the effect of temperature on SPP1 irreversible binding to the wild type and to a strain (CSJ3_gtaC) virtually devoid of reversible adsorption capacity but overproducing YueB by performing adsorption assays and extracting _k_ads values as in Fig. 5. We tested temperatures between 18 and 37°C because within this range k_1 is approximately constant (see Fig. 2B). Irreversible adsorption to the wild type was clearly accelerated by increasing T, whereas the increase of k_ads was much less pronounced with strain CSJ3_gtaC (Fig. 6). By performing simultaneous measurements of total and irreversible adsorption to CSJ3_gtaC, we observed that SPP1 interaction with this strain is essentially irreversible (data not shown), indicating that phages bound to YueB are no longer recoverable.

FIG. 6.

Effect of temperature on SPP1 irreversible adsorption. Cultures of strains L16601 (▵) and CSJ3_gtaC_ (□) were grown to an _A_600 of 0.8 and equilibrated at 18, 24, 30, and 37°C before SPP1 addition. Irreversible adsorption constants (_k_ads, from three independent assays) were extracted from exponential fitting curves as described in Fig. 5. Error bars are represented.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, the only report of the involvement of glucosylated teichoic acids in SPP1 adsorption to B. subtilis cells is more than 30 years old (42). Adsorption of SPP1 to strains carrying gtaC, gtaB, or gtaA (i.e., tagE) mutations was reduced relative to the wild type; however, SPP1 could still plate on these mutants, whereas the same mutations conferred resistance to φ29 and SPO1. We can now explain the results in this early study. Glucosylated teichoic acids participate in reversible SPP1 adsorption; in their absence, SPP1 binding to the membrane protein YueB, the receptor that triggers viral DNA ejection, can still occur, although at considerably lower rates. This explains the SPP1 capacity to infect B. subtilis mutant strains devoid of reversible adsorption receptors.

Our genetic analysis and the adsorption studies (Fig. 3 and 4) indicate that SPP1 reversible interaction with the host cell surface involves glucosyl residues of poly(Gro-P) WTA and that receptor activity cannot be substituted by glucosylated poly(ribitolphosphate) WTA. In contrast to lactobacillus phages (29), the d-alanine substituent of the poly(Gro-P) backbone does not affect SPP1 adsorption. Identical _K_eq values were measured in CSJ1 and in a derivative mutant strain dltA (C. Baptista, unpublished data).

We observed distinct levels of reversible adsorption inhibition depending on the type of mutation impairing glucosylation of WTA. Mutations preventing the synthesis of UPD-Glc (gtaC and gtaB), which affect the composition of different cell wall polymers, had the most drastic effect. Similar effects were previously reported for B. subtilis phage φ25 (13). The greater impact of gta mutations compared to tagE could also be the result of a residual level of glucosylation in tagE strains by another cell glucosyltranferase(s) acting on the available pool of UDP-Glc.

The results presented here clearly show that reversible adsorption has a major contribution for the overall SPP1 infection process. The cell wall mutations that significantly decrease SPP1 reversible adsorption proportionally affect irreversible adsorption and plating efficiency (Fig. 5 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The importance of reversible adsorption is particularly evident in liquid medium, where its inhibition leads to a much reduced rate of SPP1 irreversible binding to YueB. Quite strikingly, however, we also found that the rate of SPP1 irreversible adsorption is mainly determined by the rate of phage release from reversible receptors, in a way that a decrease in _k_2 results in a lower _k_ads value (Fig. 6). In fact, phage release from WTA is the major temperature-limited step in the whole process of adsorption. Over a temperature range where _k_1 is essentially constant, high temperatures promote faster dissociation from reversible receptors and result in higher irreversible adsorption rates.

The temperature dependence of the SPP1 dissociation rate from reversible receptors was consistent with the Arrhenius law, allowing estimation of an activation energy of 22.6 kcal/mol for phage release. Interestingly, this value is comparable to the activation energy required for triggering of SPP1 DNA ejection in vitro by YueB (29.5 kcal/mol [30]). Therefore, we infer that phage release from reversible receptors is maximal when the system's energy is close to the value allowing productive interaction with receptor YueB.

We propose a model for reversible adsorption as a mechanism used by SPP1 for fast recognition of receptor YueB. In the context of a wild-type cell envelope the vast majority of SPP1 particles rapidly adsorb to WTA because the concentration of these polymers in the cellular surface exceeds by far that of YueB. At the temperature routinely used for B. subtilis growth (37°C) phages will be bound for only a few seconds being immediately released for subsequent adsorption/desorption cycles. This strategy allows a dynamic association with reversible receptors permitting SPP1 to “scan” the cellular surface until it is captured by YueB. At lower temperatures WTA retains SPP1 for longer periods, increasing the time required for YueB recognition.

SPP1 adsorption thus seems to follow the so-called strategy of reduction of dimensionality (RD) as a means to increase the rate of irreversible binding (1, 3). According to RD theory, phage particles initially search a bacterium by means of three-dimensional movements. Association with reversible receptors restricts phages to diffuse only laterally, as in a two-dimensional fluid, until they encounter irreversible receptors. This RD results in enhancement of the binding rate to irreversible receptors. As observed by Berg and Purcell (3), two-dimensional diffusion is advantageous to binding only if reversible association is strong enough to keep phage on the bacterial surface but at the same time is weak enough to allow phage lateral jumping. This requirement seems to be fulfilled by the B. subtilis/SPP1 system.

The model here presented probably applies to other phages with a two-step adsorption process involving two different cellular receptors, such as lactococcal phage c2, which uses wall carbohydrates for reversible adsorption and the YueB homologous protein Pip for irreversible binding (12, 25), and phage T5, which targets lipopolysaccharide as a means to facilitate FhuA recognition (14, 15). In contrast, phage λ, which apparently targets a single receptor (LamB) for both steps of adsorption, seems to follow a completely different strategy. In this case, reversible adsorption (_k_1) was shown to be weakly dependent on the temperature, whereas phage dissociation (_k_2) and irreversible binding (_k_3) are completely unaffected by this parameter (24).

It is interesting that adsorption of the B. subtilis phages φ29 (Podoviridae) and φ25 (Myoviridae) also involves glucosylated WTA and a membrane receptor (16, 42, 43). These phages exhibit, however, some deviations from the SPP1 adsorption mechanism. Although adsorption of phage φ29 to isolated cell walls is completely reversible, mutations impairing glucosylation of WTA result in phage resistance (16, 43). Mutations gtaB and gtaC also confer resistance to φ25 (42). In addition, φ25 cannot be released as an infective virus particle after adsorption to wild-type cell walls since the interaction triggers tail contraction, although without phage DNA release (43).

It seems therefore that in these phages the reversible step is essential to allow a subsequent interaction with membrane receptors. In contrast, reversible adsorption only favors encounters between SPP1 and YueB and is not an essential prerequisite that “activates” the phage for a subsequent interaction with YueB.

Supplementary Material

[Supplemental material]

Acknowledgments

We thank V. Lazarevic, R. Losick, and J. D. Helmann for the gift of B. subtilis gta mutants and L5703, the ypfP cell wall mutant, and the dltA cell wall mutant, respectively. We thank P. Tavares and J. G. Nascimento for valuable discussions of the work and Lucia Rothman-Denes and Ian Molineux for critical reading of the manuscript and useful editorial comments.

The work of C.B. and C.S.-J. was supported by the Fundacão para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (Portugal) through fellowships BD/19675/2004 and BPD/9429/2002, respectively.

Footnotes

▿

Published ahead of print on 16 May 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adam, G., and M. Delbruck. 1968. Reduction of dimensionality in biological diffusion processes, p. 198-215. In A. Rich and N. Davidson (ed.), Structural chemistry and molecular biology. W. H. Freeman & Company, San Francisco, CA.

- 2.Adams, M. H. 1959. Bacteriophages. Wiley Interscience, New York, NY.

- 3.Berg, H. C., and E. M. Purcell. 1977. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 20193-219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birdsell, D. C., and R. J. Doyle. 1973. Modification of bacteriophage φ25 adsorption to Bacillus subtilis by concanavalin A. J. Bacteriol. 113198-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Branda, S. S., J. E. González-Pastor, E. Dervyn, S. D. Ehrlich, R. Losick, and R. Kolter. 2004. Genes involved in formation of structured multicellular communities by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1863970-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casadaban, M. J., and S. N. Cohen. 1980. Analysis of gene control signals by DNA fusion and cloning in Escherichia coli. J. Mol. Biol. 138179-207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung, C. T., S. L. Niemela, and R. H. Miller. 1989. One-step preparation of competent Escherichia coli: transformation and storage of bacterial cells in the same solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 862172-2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coyette, J., and J.-M. Ghuysen. 1968. Structure of the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus, strain Copenhagen. IX. Teichoic acid and phage adsorption. Biochemistry 72385-2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas, L. J., and M. J. Wolin. 1971. Cell wall polymers and phage lysis of Lactobacillus plantarum. Biochemistry 101551-1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle, R. J., and D. C. Birdsell. 1972. Interaction of concanavalin A with the cell wall of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 109652-658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freymond, P. P., V. Lazarevic, B. Soldo, and D. Karamata. 2006. Poly(glucosyl-_N_-acetylgalactosamine 1-phosphate), a wall teichoic acid of Bacillus subtilis 168: its biosynthetic pathway and mode of attachment to peptidoglycan. Microbiology 1521709-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller, B. L., R. G. Ivey, J. E. Trempy, and B. Hettinger-Smith. 1993. Cloning of a chromosomal gene required for phage infection of Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis C2. J. Bacteriol. 1755510-5519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Givan, A. L., K. Glassey, R. S. Green, W. K. Lang, A. J. Anderson, and A. R. Archibald. 1982. Relation between wall teichoic acid content of Bacillus subtilis and efficiency of adsorption of bacteriophages SP50 and φ25. Arch. Microbiol. 133318-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heller, K., and V. Braun. 1979. Accelerated adsorption of bacteriophage T5 to Escherichia coli F, resulting from reversible tail fiber-lipopolysaccharide binding. J. Bacteriol. 13932-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heller, K., and V. Braun. 1982. Polymannose O-antigens of Escherichia coli, the binding sites for the reversible adsorption of bacteriophage T5+ via the L-shaped tail fibers. J. Virol. 41222-227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobson, E. D., and O. E. Landman. 1977. Adsorption of bacteriophages φ29 and 22a to protoplasts of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Virol. 211223-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jorasch, P., F. P. Wolter, U. Zähringer, and E. Heinz. 1998. A UDP glucosyltransferase from Bacillus subtilis successively transfers up to four glucose residues to 1,2-diacylglycerol: expression of ypfP in Escherichia coli and structural analysis of its reaction products. Mol. Microbiol. 29419-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karamata, D., H. M. Pooley, and M. Monod. 1987. Expression of heterologous genes for wall teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis 168. Mol. Gen. Genet. 20773-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kearns, D. B., F. Chu, S. S. Branda, R. Kolter, and R. Losick. 2005. A master regulator for biofilm formation by Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 55739-749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kemp, P., L. R. Garcia, and I. J. Molineux. 2005. Changes in bacteriophage T7 virion structure at the initiation of infection. Virology 340307-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lazarevic, V., B. Soldo, N. Médico, H. Pooley, S. Bron, and D. Karamata. 2005. Bacillus subtilis α-phosphoglucomutase is required for normal cell morphology and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 7139-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Margot, P., and D. Karamata. 1996. The wprA gene of Bacillus subtilis 168, expressed during exponential growth, encodes a cell-wall-associated protease. Microbiology 1423437-3444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mauël, C., M. Young, and D. Karamata. 1991. Genes concerned with synthesis of poly(glycerol phosphate), the essential teichoic acid in Bacillus subtilis strain 168, are organized in two divergent transcription units. J. Gen. Microbiol. 137929-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moldovan, R., E. Chapman-McQuiston, and X. L. Wu. 2007. On kinetics of phage adsorption. Biophys. J. 93303-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Monteville, M. R., B. Ardestani, and B. L. Geller. 1994. Lactococcal bacteriophages require a host cell wall carbohydrate and a plasma membrane protein for adsorption and ejection of DNA. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 603204-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okubo, S., B. Strauss, and M. Stodolsky. 1964. The possible role of recombination in the infection of competent Bacillus subtilis by bacteriophage deoxyribonucleic acid. Virology 24552-562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Plisson, C., H. E. White, I. Auzat, A. Zafarani, C. São-José, S. Lhuillier, P. Tavares, and E. V. Orlova. 2007. Structure of bacteriophage SPP1 tail reveals trigger for DNA ejection. EMBO J. 263720-3728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Price, K., S. Roels, and R. Losick. 1997. A Bacillus subtilis gene encoding a protein similar to nucleotide sugar transferases influences cell shape and viability. J. Bacteriol. 1794959-4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Räisänen, L., C. Draing, M. Pfitzenmaier, K. Schubert, T. Jaakonsaari, S. von Aulock, T. Hartung, and T. Alatossava. 2007. Molecular interaction between lipoteichoic acids and Lactobacillus delbrueckii phages depends on d-alanyl and α-glucose substitution of poly(glycerophosphate) backbones. J. Bacteriol. 1894135-4140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raspaud, E., T. Forth, C. São-José, P. Tavares, and M. de Frutos. 2007. A kinetic analysis of DNA ejection from tailed phages revealing the prerequisite activation energy. Biophys. J. 933999-4005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riva, S., M. Polsinelli, and A. Falaschi. 1968. A new phage of Bacillus subtilis with infectious DNA having separable strands. J. Mol. Biol. 35347-356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossmann, M. G., V. V. Mesyanzhinov, F. Arisaka, and P. G. Leiman. 2004. The bacteriophage T4 DNA injection machine. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14171-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 3rd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 34.Santos, M. A. 1991. Bacteriófagos de Bacillus subtilis do grupo SPP1: características gerais, especificidade de adsorção e organização genómica. Ph.D. thesis. University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal.

- 35.São-José, C., C. Baptista, and M. A. Santos. 2004. Bacillus subtilis operon encoding a membrane receptor for bacteriophage SPP1. J. Bacteriol. 1868337-8346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.São-José, C., S. Lhuillier, R. Lurz, R. Melki, J. Lepault, M. A. Santos, and P. Tavares. 2006. The ectodomain of the viral receptor YueB forms a fiber that triggers ejection of bacteriophage SPP1 DNA. J. Biol. Chem. 28111464-11470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.São-José, C., M. de Frutos, E. Raspaud, M. A. Santos, and P. Tavares. 2007. Pressure built by DNA packing inside virions: enough to drive DNA ejection in vitro, largely insufficient for delivery into the bacterial cytoplasm. J. Mol. Biol. 374346-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Soldo, B., V. Lazarevic, P. Margot, and D. Karamata. 1993. Sequencing and analysis of the divergon comprising gtaB, the structural gene of UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Gen. Microbiol. 1393185-3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vagner, V., E. Dervyn, and S. D. Ehrlich. 1998. A vector for systematic gene inactivation in Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 1443097-3104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vinga, I., C. São-José, M. A. Santos, and P. Tavares. 2006. Bacteriophage entry in the host cell, p. 165-205. In G. Wegrzyn (ed.), Modern bacteriophage biology and biotechnology. Research Signpost, Trivandrum, India.

- 41.Yasbin, R. E., G. A. Wilson, and F. E. Young. 1973. Transformation and transfection in lysogenic strains of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Bacteriol. 113540-548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yasbin, R. E., V. C. Maino, and F. E. Young. 1976. Bacteriophage resistance in Bacillus subtilis 168, W23, and interstrain transformants. J. Bacteriol. 1251120-1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young, F. E. 1967. Requirement of glucosylated teichoic acid for adsorption of phage in Bacillus subtilis 168. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 582377-2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young, M., C. Mauël, P. Margot, and D. Karamata. 1989. Pseudo-allelic relationship between non-homologous genes concerned with biosynthesis of polyglycerol phosphate and polyribitol phosphate teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis strains 168 and W23. Mol. Microbiol. 31805-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[Supplemental material]