Development of neural stem cell in the adult brain (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Feb 1.

Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008 May 29;18(1):108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.04.001

Summary

New neurons are continuously generated in the dentate gyrus of the mammalian hippocampus and in the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles throughout life. The origin of these new neurons is believed to be from multipotent adult neural stem cells. Aided by new methodologies, significant progress has been made in the characterization of neural stem cells and their development in the adult brain. Recent studies have also begun to reveal essential extrinsic and intrinsic molecular mechanisms that govern sequential steps of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus and subventricular zone/olfactory bulb, from proliferation and fate specification of neural progenitors, to maturation, navigation and synaptic integration of the neuronal progeny. Future identification of molecular mechanisms and physiological functions of adult neurogenesis will provide further insight into the plasticity and regenerative capacity of the mature central nervous system.

Introduction

Since the seminal finding by Altman and colleagues on the presence of new neurons in the adult rodent brain in the 1960s [1], persistent neuronal generation has been demonstrated in essentially all mammals, including humans [2–4]. Now adult neurogenesis is generally considered as an active process encompassing proliferation and fate specification of adult neural progenitors, and their subsequent differentiation, maturation, navigation and functional integration into the existing neuronal circuitry [3]. Within the intact adult mammalian CNS, active neurogenesis occurs in two discrete “neurogenic” regions: the subgranular zone (SGZ) of dentate gyrus in the hippocampus for dentate granule cells, and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles in the forebrain for interneurons in the olfactory bulb (Figure 1A)[2–4]. Accumulating evidence suggests essential roles of these new neurons in specific brain functions, such as learning, memory, olfaction and mood modulation [4]. The origin of new neurons is believed to be from multipotent adult neural stem cells (NSCs), yet their exact identity is still under debate and their multipotency at the clonal level in vivo has not been universally demonstrated. Multipotent NSCs capable of long-term self-renewal and generating multiple neural lineages, including astrocytes, oligodendrocytes and functional neurons, have been derived from regions throughout the adult CNS [3]. Whether and to what extent active neurogenesis occurs outside the two “neurogenic” regions in the intact mammalian CNS in vivo is still under debate. Injuries and pathological stimuli, such as stroke, do appear to activate the neurogenesis program outside of “neurogeneic” regions [3]. Adult neurogenesis also occurs in the peripheral nervous system (PNS), such as generation of olfactory neurons in the olfactory epithelium [5] and neural crest lineages in the carotid body [6].

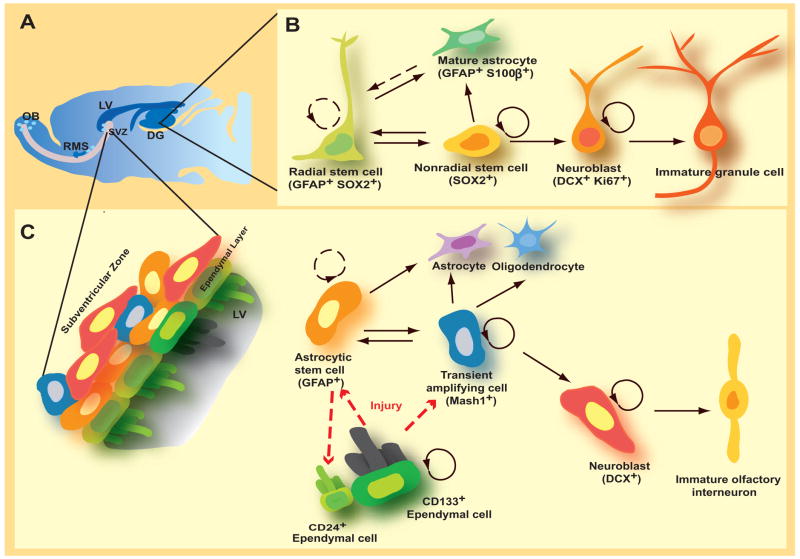

Figure 1.

Models on the identities of potential quiescent neural stem cells in the adult brain. (A). Two neurogenic regions in the adult brain: the subgranular zone (SGZ) in the dentate gyurs (DG) of the hippocampus and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles (LV). (B). Potential lineage relationships in the adult SVZ. (C). Potential lineage relationships in the adult SGZ.

Adult neurogenesis recapitulates the complete process of neuronal development in the mature CNS environment [3,4]. Advances in methodologies to detect new neurons have greatly facilitated the characterization of the basic process of adult neurogenesis and its dynamic regulation by a variety of physiological, pathological and pharmacological stimuli [3,4]. The molecular mechanisms regulating adult neurogenesis are just beginning to be revealed. Here we review recent progress in our understanding of endogenous NSCs and their normal development in the adult hippocampus and forebrain in vivo. A large number of studies on modulation of adult neurogenesis were reviewed elsewhere [4].

Neural stem cells in the adult brain

NSCs represent a special somatic cell type that has capacity for long-term self-renewal and generating different neural lineages. The identity (or identities) of adult NSCs, which are believed to be largely quiescent in vivo, has been under debate (Figure 1B & C). The prevailing model based on a series of genetic tracing, pharmacological ablation, morphological and immunocytochemistry analysis suggests that special astrocytes expressing glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and exhibiting certain radial glial properties are adult NSCs in the SVZ and SGZ [2]. Upon injury CD133+ ependymal cells lining ventricles in the mammalian forebrain may be activated, transforming into radial glia-like cells and serving as adult NSCs [7–9]. In the adult SGZ, a select population of cells that express sex determining region Y-box 2 (Sox2) and are capable of giving rise to more Sox2+ cells as well as neurons and astrocytes have been suggested to be adult NSCs [10••]. Although not definitive, this study provided evidence for the self-renewal and multipotency of NSCs at the single-cell level in the adult brain. Taken together, these findings highlight the complexity of the fundamental issue about the identity of NSCs in vivo. It is possible that distinct cells in the adult CNS can serve as NSCs in mediating neurogenesis under normal conditions or after dramatic injuries, similar to adult neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium [5].

The properties of adult NSCs remain to be fully characterized. For example, the existence of a tri-potent NSC with capacity to generate neurons, astrocytes and oligodendrocytes in the adult brain remains to be demonstrated at the clonal level in vivo. Can a single adult NSC give rise to multiple neuronal subtypes? Adult NSCs derived from rat hippocampus, which endogenously only give rise to dentate granule cells, generate multiple neuronal subtypes in culture [3] as well as olfactory interneurons after transplantation into the adult forebrain [11]. However, a recent in vivo mapping and transplantation study suggests that NSCs in the postnatal SVZ are heterogeneous and restricted in their ability to generate different neuronal subtypes in the olfactory bulb [12••]. It is likely that a variety of spatially located niches regulate the generation of the diversity of interneurons in the olfactory bulb [12••]. Further engineering and application of new genetic tools for lineage tracing at the clonal level in vivo will help to solve current controversies and reveal identities and properties of adult NSCs. For example, Mosaic Analysis with Double Markers (MADM) in mice allows simultaneous labeling and gene knockout in clones of NSCs [13]. A modified “Brainbow” system [14] using a NSC specific promoter may be used for clonal fate mapping of adult NSCs in vivo.

Development of neural stem cells in the adult brain

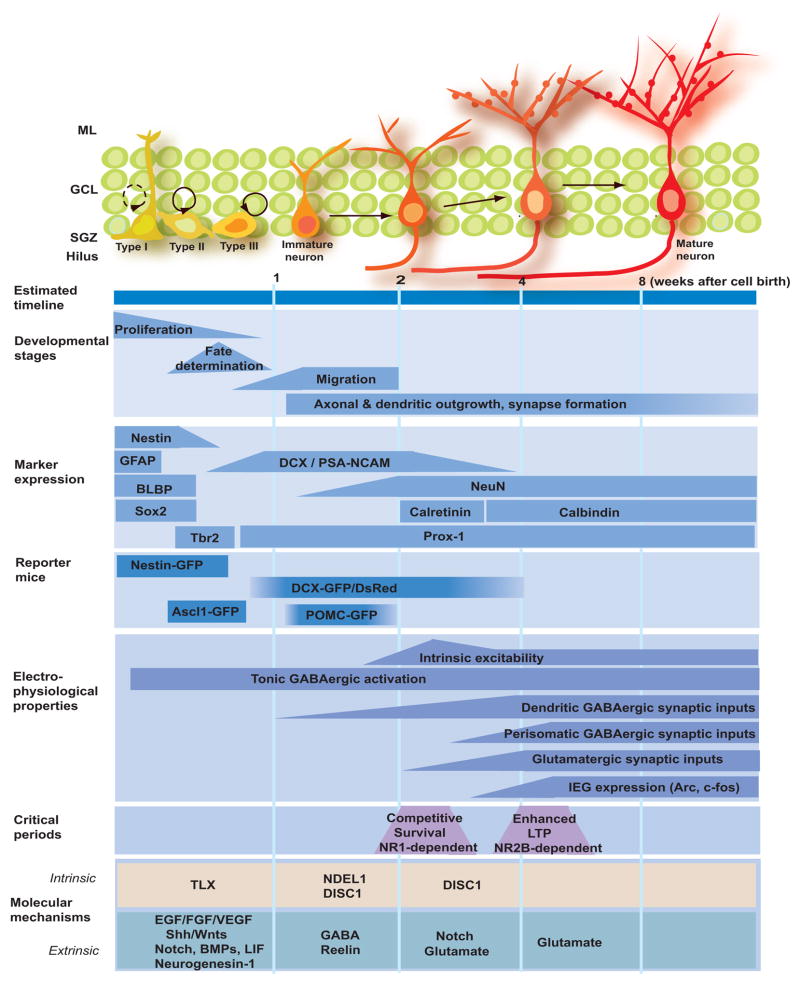

As in other somatic stem cell systems, the local environment, or “niche”, maintains the adult NSCs and regulates their development in vivo [3,4]. Multiple cell types have been implicated as niche components, including astrocytes, endothelial cells, ependymal cells, local mature neurons and the immature progeny of adult NSCs [3,4]. Significant progress has been made during the past few years in the characterization of the neurogenesis process and identification of key regulatory niche signals. In particular, studies based on BrdU labeling and immunohistochemical markers have provided a detailed description of a series of intermediate developmental stages during hippocampal neurogenesis in vivo [15,16](Figure 2). Engineered onco-retroviruses and reporter mice provide essential tools for detailed characterization of adult NSC development in vivo using confocal and electron microscopy, electrophysiology and time-lapse imaging. Genetic manipulation of adult NSCs using these approaches have further revealed underlying molecular mechanisms [17• •,18•,19] and physiological functions of adult neurogenesis [20] in vivo.

Figure 2.

Adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Summary of the current knowledge on the development of neural stem cells during adult hippocampal neurogenesis in young adult mice as characterized by estimated timeline, developmental stages, expression of specific markers, physiological properties, critical periods and potential molecular mechanisms. ML: molecular layer; GCL: granule cell layer; SGZ: subgranular zone; GFAP: gial fibrillary acidic protein; BLBP: brain lipid-binding protein; DCX: doublecortin; NeuN: neuronal nuclei; PSA-NCAM: the polysialylated form of the neural cell adhesion molecule NCAM; POMC: pro-opiomelanocortin; IEG: immediate early gene; LTP: long-term potentiation; TXL: tailless; EGF: epidermal growth factor; FGF: fibroblast growth factor; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; BMP: bone morphogenetic protein; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid; DISC1: disrupted-in-schizophrenia 1.

Maintenance, proliferation and fate specification of adult neural stem cells

Continuous neurogenesis in the SVZ and SGZ throughout life suggest a sustained maintenance of adult NSCs. Hedgehog signaling is activated in quiescent adult NSCs [21] and appears to be required for both establishment and maintenance of proper NSC pools in the adult SVZ and SGZ [22,23]. In addition, expression of leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) promotes the self-renewal of adult NSC and prevents their differentiation, leading to an expansion of the NSC pool in the adult SGZ [24].

During the course of adult neurogenesis, NSCs go through a number of stages with proliferation capacity, including NSCs, transient amplifying progenitors and neuroblasts [15](Figure 1 & 2). A variety of physiological, pathological and pharmacological stimuli have been shown to regulate cell proliferation during adult neurogenesis in the SGZ and SVZ, such as physical exercise, seizures, stroke and antidepressant treatments [3,4]. Analysis of marker expression using immunohistochemistry and in reporter mice has pinpointed the specific cell type(s) that are responsive to these stimuli. For example, kainic acid-induced seizures promote proliferation of DCX+ neuroblasts, but not nestin+ progenitors [25], whereas the antidepressant fluoxetine appears to target both nestin+GFAP− progenitors and DCX+ neuroblasts [16] in the adult SGZ. Growth factor signaling is the major mechanism underlying regulation of cell proliferation, including fibroblast growth factors (FGFs), epidermal growth factor (EGF), neuregulins (NRGs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF)[3,4](Figure 2). Several neurotransmitters, such as GABA, also regulate cell proliferation during adult neurogenesis [4,26].

Generation of new neurons is largely restricted to the adult SVZ and SGZ, whereas astrocytes and oligodendrocytes are continuously born throughout the mature CNS. The fate choice of adult NSC is likely to be regulated by the neurogenic “niche” signals. Astrocyte-derived Wnts instruct neuronal fate specification of adult NSCs in vitro and Wnt-signaling promotes new neuron production in the adult dentate gyrus in vivo [27]. On the other hand, bone morphogenic proteins (BMPs) promote glia differentiation of NSCs derived from the adult SVZ [28] and hippocampus in vitro [29]. Such gliogenic effects are blocked by two BMP antagonist noggin [28] and neurogenesin-1 [30], resulting in neuronal differentiation. Interestingly, noggin is expressed by ependymal cells adjacent to the adult SVZ [28] and neurogenesin-1 is expressed by astrocytes and granule cells in the dentate gyrus [30]. In the dentate gyrus, transgenic overexpression of BMP4 increases the number of mature astrocytes, but depletes the GFAP+ progenitor cell pool, whereas transgenic inhibition of BMP signaling increases the size of the GFAP+ progenitor cell pool but reduces the overall numbers of astrocytes [29]. Similarly, ectopic expression of noggin promotes neuronal fate specification of SVZ progenitors transplanted into the adult striatum [28]. In the adult SVZ, however, conditional deletion of Smad4, a downstream effector of BMP, in adult NSCs or infusion of noggin impairs neurogenesis and leads to an increases in the oligodendrocyte production [31]. The seemingly differential effects of BMP signaling in regulating adult SVZ NSCs in different experimental settings remain to be reconciled in the future.

Navigation of newborn neurons in the adult brain: migration and nerve guidance

Despite the inhibitory CNS environment for mature neuron regeneration, newborn neurons exhibit extensive migration and nerve growth in a directed manner to reach their targets [3]. During adult SVZ neurogenesis, new neurons migrate through the rostral migratory stream (RMS) to reach the olfactory bulb, and then settle in distinct neuronal layers through radial migration. Interestingly, beating of the cilia by ependymal cells appear to set up concentration gradients of guidance molecules such as slits to direct migration of neuroblasts [32]. A number of adhesion molecules (e.g. β1-integrin, PSA-NCAM, Tenascin-R) and extracellular cues (e.g. GABA, NRGs and Slits) have been shown to regulate the stability, motility or directionality of neuronal migration [3,4]. In the dentate gyrus, new neurons migrate locally into the inner granule cell layer, possibly through radial migration. Reelin signaling prevents new neurons from migrating into the hilus region; loss of reelin expression from local interneurons after pilocarpine-induced seizures may explain the ectopic hilar localization of new granule cells [33]. Recent studies also identified intrinsic regulators of migration and positioning for adult-born neurons. For example, deletion of DCX in newborn neurons causes severe morphologic defects and delayed migration along the RMS [34], whereas knockdown of Disrupted-in-Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) or NDEL1 in newborn granule cells leads to overextended migration and aberrant positioning in the outer granule cell layer and molecular layer [19].

Analysis of axonal and dendritic development of new neurons using retrovirus-mediated labeling has revealed similar patterns of targeting as their neighboring mature neurons [3]. For example, newborn dentate granule cells rapidly extend their axons through the hilus region to reach the CA3 region within two weeks after birth, while their dendrites reach the molecular layer within one week and continue to elaborate for at least four weeks [17,35,36•]. The environmental cues that guide axons and dendrites of newborn neurons in the adult brain remain to be identified. A number of molecular players have been shown to regulate the tempo of dendritic development. For example, GABA-induced depolarization [17] and Notch signaling [37] promote dendritic growth, whereas DISC1 limits dendritic initiation and outgrowth of new neurons [19] during adult hippocampal neurogenesis. New periglomerular cells and granule cells in the olfactory bulb are more heterogeneous in patterns of growth [38•]. The accessibility of olfactory bulb for in vivo multiphoton confocal imaging of new neurons allows time-lapse analysis of detailed structural dynamics in intact animals [38•]. Together with genetic and behavioral manipulations, such a system holds promise to provide novel insight into the neuronal development and plasticity in the adult brain.

Synaptic integration of new neurons in the adult brain

Despite significant differences in the local environment, the synaptic integration of newborn neurons follows the same milestones to incorporate into the existing circuitry as in embryonic and early postnatal development. Interestingly, neural progenitors and immature neurons are tonically activated by ambient GABA before receiving any functional synaptic inputs during adult SVZ and SGZ neurogenesis [26]. For new dentate granule cells, there is a sequence in the initiation of types formation, with dendritic GABAergic synaptic inputs (~ 1 week after birth) started first, followed by glutamatergic inputs (~ 2 weeks), and finally perisomatic GABAergic inputs (Figure 2)[39]. During the initial stage of neuronal maturation, GABA depolarizes newborn neurons due to the high chloride content and promotes formation of GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic inputs to nee neurons in vivo [17]. Knockdown of DISC1 also accelerates formation of synaptic inputs to newborn dentate granule cells [19]. In the olfactory bulb, new granule cells receive functional synaptic inputs from mitral cells (~ 10 days)[40]. New periglomerular cells receive inputs from olfactory neurons, which go through a series of maturation changes with a gradual increase in the ratio of AMPARs over NMDARs and a decrease in the ratio of NR2B subunit containing NMDARs [41].

Very little is known about synaptic outputs of newborn neurons in the adult brain. It remains to be determined whether new neurons innervate the same targets as their neighboring mature neurons. In the hippocampus, mature granule cells innervate multiple neuronal subtypes (e.g. basket cells and mossy cells) in the hilus region and form large mossy fiber boutons to pyramidal neurons and filopodial synaptic contacts to interneurons in the CA3 region. In the olfactory bulb, mature granule cells lack axons and instead form dendritic-dendritic synapses with mitral cells, whereas periglomerular cells make axonal synapses with mitral cells. Future studies using electron microscopy and emerging optogenetic tools, such as channelrhodopsin, may facilitate studies of synaptic outputs by adult-born neurons.

Critical periods during the development of new neurons in the adult brain

How can a small population of adult-born neurons make a significant impact on brain functions? Synaptic integration of new neurons is likely to be required for their contribution to brain functions. One hypothesis is that new neurons are preferentially incorporated into special circuitry to support specific brain functions, as suggested by findings based on the expression of immediate early genes such as Arc and c-Fos [42•,43,44]. Recent studies also have identified two critical periods during adult hippocampal neurogenesis that may contribute to a selective incorporation of new neurons into the adult circuitry. First, studies using retrovirus-mediated knockout of NR1 in newborn granule cells suggest that the survival of these new neurons is competitively regulated by their own NMDARs during 2–3 week window when these new neuron are born [18]. Enriched environment-induced survival and integration of new granule cells share the same critical period [44]. Second, systematic analysis of synaptic plasticity of glutamatergic synaptic inputs to newborn granule cells has identified a critical period when they neurons are 4–6 weeks old and exhibit NR2B-dependent enhanced long-term potentiation, which may instruct new neurons to refine their inputs in response to environmental stimulation [41].

Contrasts between early postnatal and adult neurogenesis

Despite many similarities between early postnatal and adult neurogenesis as discussed above, major differences have been identified. Adult neurogenesis is dynamically regulated by stimuli that modulate the activity of the existing neuronal circuitry. For example, seizures and antidepressant treatment enhance proliferation of adult neural progenitors and accelerate dendritic development of newborn neurons in the adult hippocampus [45–48]. Adult neurogenesis also exhibits a more prolonged time course of neuronal maturation. For example, dendritic development of adult-born dentate granule cells lasts more than four weeks and formation and maturation of synaptic spines continues over eight weeks after they are born, while the same process occurs largely within 2 weeks during early postnatal dentate development [17,35]. The physiological significance of such a slow tempo of neuronal development in the adult brain is not well understood. Interestingly, a dramatic acceleration of neuronal development, such as after recurrent seizures [45] or knockdown of DISC1 [19], leads to aberrant incorporation of new neurons into the existing circuitry.

Conclusions

Forty years after the initial discovery of adult neurogenesis in the rodent brain [1], we now not only have obtained significant knowledge about the origin and development of new neuron in the adult brain, but also appreciate that adult neurogenesis is a highly-coordinated process with physiological significance. Future mechanistic studies on intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms regulating adult neurogenesis may offer unique insight into fundamental principles of neural development and plasticity in general. Development of new technologies, including genetically modified animal models and imaging approaches, will help to resolve current controversies, to further understand the molecular basis and physiological functions of adult neurogenesis, and to explore adult human neurogenesis [49,50•]. A better understanding of endogenous adult neurogenesis will provide a blueprint to investigate induced and aberrant neurogenesis in different CNS regions and, in addition, may help developing strategies to repair the damaged brain after injury or in various neurological diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health (NS047344, AG024984), McKnight Scholar Award, The Packard center for ALS and MDA, Maryland Stem Cell research Fund to H.S., by National Institute of Health (NS048271), Klingenstein Fellowship Award in the Neurosciences, March of Dimes, and Adelson Medical Research Foundation to G-l.M. We apologize for not citing many valuable original literatures due to space limits.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Altman J, Das GD. Post-natal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature. 1965;207:953–956. doi: 10.1038/207953a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez-Buylla A, Lim DA. For the long run: maintaining germinal niches in the adult brain. Neuron. 2004;41:683–686. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ming GL, Song H. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:223–250. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.051804.101459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao C, Deng W, Gage FH. Mechanisms and functional implications of adult neurogenesis. Cell. 2008;132:645–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leung CT, Coulombe PA, Reed RR. Contribution of olfactory neural stem cells to tissue maintenance and regeneration. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:720–726. doi: 10.1038/nn1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardal R, Ortega-Saenz P, Duran R, Lopez-Barneo J. Glia-like stem cells sustain physiologic neurogenesis in the adult mammalian carotid body. Cell. 2007;131:364–377. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson CB, Momma S, Clarke DL, Risling M, Lendahl U, Frisen J. Identification of a neural stem cell in the adult mammalian central nervous system. Cell. 1999;96:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80956-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coskun V, Wu H, Blanchi B, Tsao S, Kim K, Zhao J, Biancotti JC, Hutnick L, Krueger RC, Jr, Fan G, et al. CD133+ neural stem cells in the ependyma of mammalian postnatal forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1026–1031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang RL, Zhang ZG, Wang Y, LeTourneau Y, Liu XS, Zhang X, Gregg SR, Wang L, Chopp M. Stroke induces ependymal cell transformation into radial glia in the subventricular zone of the adult rodent brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1201–1212. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10••.Suh H, Consiglio A, Ray J, Sawai T, D’Amour KA, Gage FH. In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.002. Using Sox2-GFP transgenic mice and retrovirus-mediated lineage-tracing analysis, the authors provided evidence suggesting that some Sox2+ cells exhibit capacity for self-renewal and multipotency at the single-cell level in the adult hippocampus in vivo. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suhonen JO, Peterson DA, Ray J, Gage FH. Differentiation of adult hippocampus-derived progenitors into olfactory neurons in vivo. Nature. 1996;383:624–627. doi: 10.1038/383624a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12••.Merkle FT, Mirzadeh Z, Alvarez-Buylla A. Mosaic organization of neural stem cells in the adult brain. Science. 2007;317:381–384. doi: 10.1126/science.1144914. Based on lineage tracing of restricted patch of NSCs marked by locally injected virus as well as transplantation experiments, the authors showed the heterogeneity and restricted potential for neuronal subtype differentiation of NSCs in the early postnatal and adult SVZ. These studies also suggest that a variety of spatially located niches exist in regulating the generation of the diversity of interneurons in the olfactory bulb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zong H, Espinosa JS, Su HH, Muzumdar MD, Luo L. Mosaic analysis with double markers in mice. Cell. 2005;121:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livet J, Weissman TA, Kang H, Draft RW, Lu J, Bennis RA, Sanes JR, Lichtman JW. Transgenic strategies for combinatorial expression of fluorescent proteins in the nervous system. Nature. 2007;450:56–62. doi: 10.1038/nature06293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kempermann G, Jessberger S, Steiner B, Kronenberg G. Milestones of neuronal development in the adult hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Encinas JM, Vaahtokari A, Enikolopov G. Fluoxetine targets early progenitor cells in the adult brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:8233–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601992103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17••.Ge S, Goh EL, Sailor KA, Kitabatake Y, Ming GL, Song H. GABA regulates synaptic integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Nature. 2006;439:589–593. doi: 10.1038/nature04404. Using retrovirus-mediated birth-dating and labeling, the authors showed the time course and sequential integration of new neurons into the existing neuronal circuitry. Furthermore, using retrovirus-based “single-cell genetic” approach, the authors provided evidence suggesting essential roles of GABA-induced excitation in regulating development of the new neurons. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18•.Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006;442:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. Using retrovirus-mediated expression of Cre recombinase in adult neural progenitors of the NR1 conditional knockout mice, the authors showed that NR1 is required for competitive survival of new neurons during a critical period when the new neurons are 2–3 weeks old, the same window for enriched environment-induced survival and incorporation as shown in [44]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.Duan X, Chang JH, Ge S, Faulkner RL, Kim JY, Kitabatake Y, Liu XB, Yang CH, Jordan JD, Ma DK, et al. Disrupted-In-Schizophrenia 1 regulates integration of newly generated neurons in the adult brain. Cell. 2007;130:1146–1158. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.010. Using retrovirus-mediated expression of shRNA to knockdown of DISC1 in proliferating neural progenitors and their progeny, the authors showed that DISC1 serves as a key tempo regulator of new neuron development in the adult brain, including neuronal morphogenesis, migration, dendritic development and synapse formation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang CL, Zou Y, He W, Gage FH, Evans RM. A role for adult TLX-positive neural stem cells in learning and behaviour. Nature. 2008;451:1004–1007. doi: 10.1038/nature06562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn S, Joyner AL. In vivo analysis of quiescent adult neural stem cells responding to Sonic hedgehog. Nature. 2005;437:894–897. doi: 10.1038/nature03994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balordi F, Fishell G. Hedgehog signaling in the subventricular zone is required for both the maintenance of stem cells and the migration of newborn neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:5936–5947. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1040-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han YG, Spassky N, Romaguera-Ros M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Aguilar A, Schneider-Maunoury S, Alvarez-Buylla A. Hedgehog signaling and primary cilia are required for the formation of adult neural stem cells. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:277–284. doi: 10.1038/nn2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bauer S, Patterson PH. Leukemia inhibitory factor promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in the adult brain. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12089–12099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3047-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jessberger S, Romer B, Babu H, Kempermann G. Seizures induce proliferation and dispersion of doublecortin-positive hippocampal progenitor cells. Exp Neurol. 2005;196:342–351. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ge S, Pradhan DA, Ming GL, Song H. GABA sets the tempo for activity-dependent adult neurogenesis. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lie DC, Colamarino SA, Song HJ, Desire L, Mira H, Consiglio A, Lein ES, Jessberger S, Lansford H, Dearie AR, et al. Wnt signalling regulates adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Nature. 2005;437:1370–1375. doi: 10.1038/nature04108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim DA, Tramontin AD, Trevejo JM, Herrera DG, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Noggin antagonizes BMP signaling to create a niche for adult neurogenesis. Neuron. 2000;28:713–726. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonaguidi MA, McGuire T, Hu M, Kan L, Samanta J, Kessler JA. LIF and BMP signaling generate separate and discrete types of GFAP-expressing cells. Development. 2005;132:5503–5514. doi: 10.1242/dev.02166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ueki T, Tanaka M, Yamashita K, Mikawa S, Qiu Z, Maragakis NJ, Hevner RF, Miura N, Sugimura H, Sato K. A novel secretory factor, Neurogenesin-1, provides neurogenic environmental cues for neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:11732–11740. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-37-11732.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colak D, Mori T, Brill MS, Pfeifer A, Falk S, Deng C, Monteiro R, Mummery C, Sommer L, Gotz M. Adult neurogenesis requires Smad4-mediated bone morphogenic protein signaling in stem cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:434–446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4374-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sawamoto K, Wichterle H, Gonzalez-Perez O, Cholfin JA, Yamada M, Spassky N, Murcia NS, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Marin O, Rubenstein JL, et al. New neurons follow the flow of cerebrospinal fluid in the adult brain. Science. 2006;311:629–632. doi: 10.1126/science.1119133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong C, Wang TW, Huang HS, Parent JM. Reelin regulates neuronal progenitor migration in intact and epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2007;27:1803–1811. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3111-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koizumi H, Higginbotham H, Poon T, Tanaka T, Brinkman BC, Gleeson JG. Doublecortin maintains bipolar shape and nuclear translocation during migration in the adult forebrain. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:779–786. doi: 10.1038/nn1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao C, Teng EM, Summers RG, Jr, Ming GL, Gage FH. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36•.Ge S, Yang CH, Hsu KS, Ming GL, Song H. A Critical Period for Enhanced Synaptic Plasticity in Newly Generated Neurons of the Adult Brain. Neuron. 2007;54:559–566. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.002. Using retrovirus-mediated birth-dating and labeling in combination with electrophysiology analysis, the authors identified a critical period when new granule cells are 4–6 weeks old and exhibit NR2B-dependent enhanced long-term potentiation with a reduced induction threshold and increased amplitude. These findings may provide the physiological mechanism for experience-dependent preferentially recruitment of new neurons into special circuits as suggested in [42]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Breunig JJ, Silbereis J, Vaccarino FM, Sestan N, Rakic P. Notch regulates cell fate and dendrite morphology of newborn neurons in the postnatal dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20558–20563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710156104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38•.Mizrahi A. Dendritic development and plasticity of adult-born neurons in the mouse olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:444–452. doi: 10.1038/nn1875. Using in vivo two-photon microscopy of lentivirus-labeled newborn neurons in the olfactory bulb, the author followed the structural dynamics of the same neuron at different stages of development and maturation with time-lapse imaging in the living animals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Esposito MS, Piatti VC, Laplagne DA, Morgenstern NA, Ferrari CC, Pitossi FJ, Schinder AF. Neuronal differentiation in the adult hippocampus recapitulates embryonic development. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10074–10086. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3114-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitman MC, Greer CA. Synaptic integration of adult-generated olfactory bulb granule cells: basal axodendritic centrifugal input precedes apical dendrodendritic local circuits. J Neurosci. 2007;27:9951–9961. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1633-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grubb MS, Nissant A, Murray K, Lledo PM. Functional maturation of the first synapse in olfaction: development and adult neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28:2919–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5550-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42•.Kee N, Teixeira CM, Wang AH, Frankland PW. Preferential incorporation of adult-generated granule cells into spatial memory networks in the dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:355–362. doi: 10.1038/nn1847. Based on expression of immediate early genes c-Fos and Arc, the authors observed preferential recruitment of newborn granule cells into circuits supporting spatial memory when new cells are 4–6 weeks old, the same time window when newborn dentate granule cells exhibit enhanced long-term potentiation from electrophysiology analysis in [36]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramirez-Amaya V, Marrone DF, Gage FH, Worley PF, Barnes CA. Integration of new neurons into functional neural networks. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12237–12241. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2195-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tashiro A, Makino H, Gage FH. Experience-specific functional modification of the dentate gyrus through adult neurogenesis: a critical period during an immature stage. J Neurosci. 2007;27:3252–3259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4941-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parent JM, Yu TW, Leibowitz RT, Geschwind DH, Sloviter RS, Lowenstein DH. Dentate granule cell neurogenesis is increased by seizures and contributes to aberrant network reorganization in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3727–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03727.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Overstreet-Wadiche LS, Bromberg DA, Bensen AL, Westbrook GL. Seizures accelerate functional integration of adult-generated granule cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4095–4103. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5508-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9104–9110. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang JW, David DJ, Monckton JE, Battaglia F, Hen R. Chronic fluoxetine stimulates maturation and synaptic plasticity of adult-born hippocampal granule cells. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1374–1384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3632-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Curtis MA, Kam M, Nannmark U, Anderson MF, Axell MZ, Wikkelso C, Holtas S, van Roon-Mom WM, Bjork-Eriksson T, Nordborg C, et al. Human neuroblasts migrate to the olfactory bulb via a lateral ventricular extension. Science. 2007;315:1243–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1136281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50••.Manganas LN, Zhang X, Li Y, Hazel RD, Smith SD, Wagshul ME, Henn F, Benveniste H, Djuric PM, Enikolopov G, et al. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy identifies neural progenitor cells in the live human brain. Science. 2007;318:980–985. doi: 10.1126/science.1147851. Using proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy for an unknown biomarker enriched in neural progenitors, the authors developed a novel method for potential quantitative analysis of neural progenitors in living humans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]