Understanding Health Care Organization Needs and Context: Beyond Performance Gaps (original) (raw)

Abstract

Significant efforts have been invested in improving our understanding of how to accelerate and magnify the impact of research on clinical practice. While approaches to fostering translation of research into practice are numerous, none appears to be superior and the evidence for their effectiveness is mixed. Lessons learned from formative evaluation have given us a greater appreciation of the contribution of context to successful implementation of quality improvement interventions. While formative evaluation is a powerful tool for addressing context effects during implementation, lessons learned from the social sciences (including management and operations research, sociology, and public health) show us that there are also powerful preimplementation tools available to us. This paper discusses how we might integrate these tools into implementation research. We provide a theoretical framework for our need to understand organizational contexts and how organizational characteristics can alert us to situations where preimplementation tools will prove most valuable.

Keywords: needs assessment, quality improvement, methods, systems analysis

Like the human body, health care systems are complex adaptive systems—“the parts have the freedom and ability to respond to stimuli in many different and fundamentally unpredictable ways.”1 Performance gaps, like medical signs and symptoms, point to a problem, but provide no specific solutions to remedy them. In medicine, diagnostic processes are used to uncover causes of signs and symptoms and point to appropriate treatments. Management science, operations research, and process engineering use the term “diagnosis” for similar efforts directed at organizations and processes.2–18 In the fields of public health, education, and psychology, the term “needs assessment” is used to reflect the focus on persons.19–32 In health care systems we are dealing with organizations, clinical processes, and persons such as providers and patients, so we draw from both traditions.

The basic questions to be answered by diagnosis/needs assessment (D/NA) are “what is causing the performance gaps? and what can we do to fix it?” We find answers through methods such as ethnographic observation, systems analysis, key informant interviews, surveys, and analysis of administrative data. We can characterize this approach as need-driven and, in fact, within these disciplines, such foundational work is considered a necessary first step.33–35

In contrast, much of health services quality improvement (QI) implementation can be characterized as solution-driven: we identify an innovation or a research finding and work toward rapid diffusion. Significant efforts have been invested in accelerating and magnifying the impact of research on practice. While approaches to fostering translation of research into practice are numerous (e.g., clinical practice guidelines, total QI), none appears to be superior36; evidence for their effectiveness is mixed.37 Formative evaluations are increasingly being conducted to understand why some interventions work while others fail,38 resulting in a greater appreciation of the contribution of context to the successful implementation of QI interventions.39,40

While formative evaluation is a powerful tool applied during implementation, lessons learned from “need-driven” traditions provide examples of powerful preimplementation tools that identify barriers to improvement that must be addressed prior to selection or implementation of an intervention. We hope to show how ideas adapted from need-driven approaches can supplement current methods and produce a more complete approach to successful implementation of evidence-based practice.

Theoretical Framework for Integrating D/NA Into Implementation

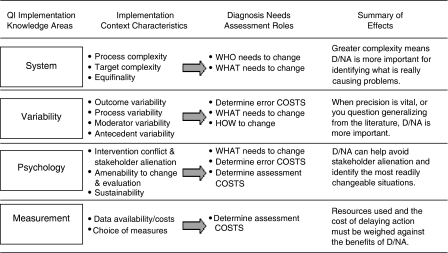

We began development of the theoretical framework with consideration of the roles of D/NA. The work of quality pioneer W. Edwards Deming guided our identification of relevant constructs. We examined experiences from the VA Colorectal Cancer Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (CRC-QUERI) to identify implementation context characteristics that are examples of these constructs. The resulting theoretical framework is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Contribution of diagnosis/needs assessment (D/NA) to quality improvement implementation.

Column one lists the knowledge areas cited by Deming41 as necessary for QI. Within each knowledge area we identified characteristics of implementation contexts that influence the need for D/NA. The third column indicates the specific role of D/NA that is most affected by the context characteristics. The final column summarizes the effects of context on the need for D/NA. The listed context characteristics are not an exhaustive set, and we hope other implementation researchers will continue to add to this theoretical framework.

Roles of D/NA

Sometimes the health care system is unable to meet expectations for a well-established, accepted practice. In others, a new innovation is not integrated into practice and we need to help it along. Once a general need for change has been established, D/NA has 3 roles: (1) identification of what behaviors or mechanisms to change, (2) identification of persons or organizational units that need to change (who); and (3) identification of ways to make changes happen (how).

Knowledge Categories

W. Edwards Deming said that in the pursuit of quality, “there is no substitute for knowledge.”41 Deming classified the types of knowledge necessary for QI into 4 categories: appreciation of systems, understanding of variation, psychologic knowledge, and knowledge about measurement.33 Within each of these categories, we identified characteristics of implementation settings affecting the importance of D/NA. In the following sections, we will briefly describe each knowledge type, related implementation context characteristics, and discuss their influence on the importance of D/NA for successful implementation.

Knowledge of a System

Awareness of how multiple systems and subsystems interact is vital to successful implementation. For example, a colorectal cancer screening and follow-up system within an integrated health care system involves the interaction of primary care, laboratory, and gastroenterology clinics, as well as external systems, such as family and community, and interactions with other components of the medical center. The goal of the colorectal cancer screening and follow-up system is to improve early detection and prompt treatment of colorectal cancers and precancerous polyps.

We have identified 3 systems characteristics that influence the need for preimplementation D/NA: the complexity of a system in terms of its (1) processes, (2) intervention targets, and (3) the potential for equifinality within the system.

Process Complexity

Process complexity is determined by both the process length and breadth. By length, we mean that the process contains sequential subprocesses. For example, in facilities that use fecal occult blood test (FOBT) for colorectal cancer screening, the length of the screening process will vary depending on the use of formal patient education or decision support systems, reminder systems, laboratory quality control and feedback systems. By process breadth, we mean the number of choices presented at decision points in the process. For example, some VA facilities use a single colorectal cancer screening modality, while others offer patients a choice of FOBT, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy. The latter systems are more complex because of the decision point of choosing a screening modality. In other VA facilities more than 1 clinic offers diagnostic follow-up, for example gastroenterology and surgery. The decision whether to route a patient to gastroenterology or surgery for colonoscopy adds to the complexity of these systems.

Implementation programs in settings with complex processes are likely to benefit from D/NA. Diagnosis/needs assessment can help avoid unintended consequences in downstream processes that may not be apparent. For example, increasing patient adherence to FOBT screening will increase laboratory workload, the need for referrals to gastroenterology, consult, scheduling, and gastroenterology procedure workload. Preimplementation D/NA that assures that downstream processes can accept increased workload is preferable to trying to fix a problem uncovered during formative evaluation.

Target Complexity

The complexity of intervention targets is indicated by the number of potential organizational units (teams, clinics, departments) or person types (providers, patients, managers) that may be foci for interventions. Again, increased complexity is associated with increased benefit from D/NA. The greater the number of organizational units or persons potentially affected by the implementation, the more we need their input prior to our work. This can prevent misunderstandings and political barriers that are more difficult to resolve once they occur. Diagnosis/needs assessment that examines the perspective of all stakeholders may reveal that the target of the intervention needs to be changed. For example, patient-directed education and screening promotion may do little to improve clinical practice if providers view screening as a low priority. The implementation team may want to begin with a provider education and motivation before implementing their patient-directed program.

Equifinality

Equifinality is the premise that in complex systems different causal paths can produce the same outcome. For example, 2 VA facilities provide follow-up within 1 year to approximately 33% of FOBT-positive patients. The process for performing follow-up can be summarized as: (1) refer the patient to gastroenterology for follow-up and schedule procedure; (2) provide the patient with bowel prep materials and instruction; and (3) the patient must show up prepped for the appointment.

Comparison of the 2 facilities' D/NA show distinct underlying causes of performance gaps. Facility A refers approximately 40% of their patients for follow-up. Eighty-three percent of those referred show up prepped for their colonoscopies. In contrast, facility B refers 75% of patients for follow-up, but only 44% show up prepped for the colonoscopy. Both facilities have the same follow-up rate (0.40 × 0.83=0.75 × 0.44=0.33) but entirely different remedies are needed. Facility A should improve referral processes while facility B should improve appointment completion and prep processes.

Knowledge of Variation

The VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative describes variations assessment as an early step in systematic QI.42 However, little guidance has been available about the types of variability that should be studied. The variability issues we have identified include tolerance for outcome variability, functional variability, and distributions of antecedent and moderator variables.

Tolerance for Outcome Variability

A clinic with low colorectal cancer screening rates may simply want to increase screening rates. This goal encompasses all screening rates greater than the current rate—a high tolerance for outcome variation. At another clinic, colorectal cancer screening may be viewed as a mission-critical activity and the tolerance for outcome variability is low. This means that the “error cost” or consequences of implementation failure are very high. Diagnosis/needs assessment is more important to in this context. Diagnosis/needs assessment will help set definite, attainable goals, highlight barriers that can be resolved prior to implementation, and increase the likelihood of “getting it right the first time.”

Functional Variability

Organizational units or persons that perform the same tasks often use different methods. When methods are adaptations to local conditions, variability enhances performance: it is functional. For example, we found that VA gastroenterology endoscopy clinics differ in allocating endoscopy resources across procedures. Some facilities use more resources for upper gastroenterology procedures while others prioritize colonoscopy. If facilities perform more upper gastroenterology procedures because of greater patient need for these procedures, then the observed variability is functional, and implementation efforts should not divert resources from upper gastroenterology procedures to improve colonoscopy performance. If the observed variability is not related to patient need, then facilities can recapture these resources, bringing them to bear on processes that will improve performance. When the reason for process variability is unknown, D/NA can be used to determine whether variations are functional.

Moderator and Antecedent Variability

When we apply existing research to new contexts we often assume the relationship between an intervention and its antecedents, moderators, and outcomes is the same in the new setting as in the setting in which the intervention was initially tested. For example, if a health promotion intervention has been shown to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in a private-sector health-maintenance organization, we may want to implement it in the VA. There are times when we have a priori reasons to question these assumptions.

For example, improving knowledge and attitudes toward preventive health care is 1 mechanism for increasing patient adherence with cancer screening. However, if a health care system has shown that existing health promotion activities have successfully improved patients' knowledge and attitudes, but screening rates remain poor, it suggests they may have reached ceiling effects on this type of intervention. In this case, we would want to assess whether fundamentally different mechanisms to improve screening should be pursued in place of additional attempts to improve knowledge and attitudes. For example, they may need to address barriers to system access.

Another example is when the health system's patients differ from those in the settings in which the intervention was originally tested, we may not find the “proven” interventions successful. Written materials are less effective with low literacy populations. If we are working with low literacy patients, we need to find new interventions. More subtle differences based in gender, socioeconomic status, or cultural differences may also exist. When doubts exist, D/NA can clarify the extent to which we can generalize from the published scientific literature to a specific setting.

Psychologic Knowledge

The psychologic issues relevant to effective implementation are intervention conflict and stakeholder alienation, amenability to change/evaluation, and the sustainability of change.

Intervention Conflict and Stakeholder Alienation

These factors are likely when system complexity is not adequately addressed prior to implementation. For example, implementing a patient-directed colorectal cancer screening promotion program in a context where providers do not feel colorectal cancer screening is a clinical priority will result in patients receiving mixed messages. A recent community health colorectal cancer screening promotion effort collected reports of providers telling patients to discard the FOBT kits that they received in the mail. Because they were not involved in implementation development, providers were alienated and resented the community health foundation's efforts.

Failure to consider downstream-unintended consequences (such as increased demand for gastroenterology services) can lead to friction between primary care and gastroenterology, or delay in access to necessary diagnostic evaluation. The net result from the patient perspective is a health care system that says, “I want you to do this procedure, I'll help you get started, but I will prevent you from finishing the process.” This type of conflict may discourage the patient, resulting in poor repeat screening levels. Such effects are difficult to reverse if discovered through formative evaluation, but can be prevented through D/NA.

Amenability to Change and Evaluation

When multiple paths may produce similar changes, it is advisable to seek the path of least resistance and work with processes and organizational units or persons most amenable to change and evaluation. Diagnosis/needs assessment can identify willing partners and motivational factors (goals, barriers, meaningful incentives) among stakeholders so the implementation program can address these issues. While this can be accomplished through formative evaluation, the earlier it is begun the less likely we are to generate ill will that will have to be overcome through iterative program changes. In summary, if there is reason to believe that potential implementation targets differ in amenability, or if amenability is thought to be universally low, D/NA becomes more important.

Sustainability of Change

Innovations and QI efforts are usually expected to become self-sustaining. The intervention is expected to produce a relatively permanent change so facilitation can be withdrawn without a loss in performance. Therefore, we need to pay careful attention to factors that promote sustainability. Many of these factors can be considered primarily psychologic in nature. For example, the impact of the intervention on social interactions within the clinical setting, whether individuals perceive changes as worthwhile or even possible, the burden an intervention may place on individuals' cognitive capacity, the difficulties people and social groups have in adapting to change, and the processes of integrating new behaviors into well-established practice.

Many of these psychologic factors are critical to the integration of the new practice into the existing workflow design. A human factors assessment can be incorporated into the D/NA43,44 to facilitate this integration. Human factors is the systematic study of how the physical and information environment shape human performance. The goal is to structure the workplace so that it is easier to do efficiently and correctly, than it is to make a mistake.

For example, a colorectal cancer QUERI program to implement an electronic event notification system (ENS) is based on a human factors analysis of how providers use information about positive lab results. Rather than interrupting the patient encounter to address lab results, the ENS groups results and presents them to the provider during a chart review work period. The system walks the provider through the action options for each patient. Increasing efficiency and removing this task from the patient encounter makes this a highly desirable solution for providers and enhances its potential sustainability.

Measurement and Testing Issues

Data availability and cost will affect the contribution that D/NA makes to implementation success. If data are readily available, you might as well look at them. In cases where the importance of D/NA is not clear, or where issues may be addressed through formative evaluation, it is reasonable to allow assessment cost to drive decisions about the nature and extent of D/NA activities. Assessment cost includes the resources put into data collection and analysis, but perhaps more importantly, assessment cost includes “opportunity cost.” What will we lose if we delay action for D/NA? Opportunity costs include morbidity, mortality, and political costs. Opportunities for action may present themselves that do not lend themselves to comprehensive D/NA. Unless there are very high error costs and pressing D/NA needs, assessment cost may drive the decision to act in these cases.

Summary and Conclusions

When we consider the organizational context of implementation in terms of systems, variation, psychologic factors, and measurement issues, the contributions and value of D/NA for fostering effective implementation becomes clear (see Fig. 1). Using D/NA, we are building an evidence base for an organization—its processes, its people, and its needs. Using the traditional health services solution-based approach, this strategy of local assessment and diagnosis will allow us to more effectively map available research evidence to the realities of each health care organization. Capitalizing on lessons learned from social science's needs-based approach, we have the opportunity to improve the quality of the research and clinical partnerships that are at the foundation of our QI implementation efforts. Beyond performance gaps, the tools of D/NA provide a theoretical framework and empirical foundation for enhancing the yield of our efforts both in terms of stakeholder value and realized gains in quality of care for patients.

Acknowledgments

This paper was provided as background material for the VA State of the Art Conference on Implementation Research, August 30–September 1, 2004. This work has been supported by VA HSR&D grants CAN 01-133, CRS 02-162, CRT 02-059, and CRS 02-163-1. The authors wish to thank the Colorectal Cancer QUERI Executive Committee and research affiliates and the VA HSR&D QUERI Director's office, Research Coordinators, and Implementation Research Coordinators for their valuable input.

REFERENCES

- 1.Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care [see comment] BMJ. 2001;323:625–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harrison MI, Shirom A. Organizational diagnosis and assessment: bridging theory and practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage. 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hellerstein J. GAP: a general approach to quantitative diagnosis of performance problems. J Network Systems Manag. 2003;11 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beer M, Spector B. Organizational diagnosis: its role in organizational learning. J Couns Dev. 1993;71:642–50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bray DW. Personnel-Centered Organizational Diagnosis. Ann: Howard; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heiming B, Lunze J. Parallel process diagnosis based on qualitative models. Int J Control. 2000;73:1061–77. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiao J, Zhang W, Zhao Z, Cha J. An integrated intelligent approach to process diagnosis in process industries. Int J Prod Res. 1999;37:2565–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim H, Yoon WC, Choi S. Aiding fault diagnosis under symptom masking in dynamic systems. Ergonomics. 1999;42:1472–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee GB, Song SO, Yoon ES. Multiple-fault diagnosis based on system decomposition and dynamic PLS. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2003;42:6145–54. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lo CH, Wong YK, Rad AB. Model-based fault diagnosis in continuous dynamic systems. ISA Trans. 2004;43:459–75. doi: 10.1016/s0019-0578(07)60161-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malony AD, Helm BR. A theory and architecture for automating performance diagnosis. Future Gener Comp Sys. 2001;18:189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paul J. Between-method triangulation in organizational diagnosis. Int J Org Anal. 1996;4:135–53. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rafferty AE, Griffin MA. Expanding organizational diagnosis by assessing the intensity of change activities. Organ Dev J. 2001;19:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schaffer J, Cinar A. Multivariable MPC system performance assessment, monitoring, and diagnosis. J Process Control. 2004;14:113–29. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shastri S, Lam CP, Werner B. A machine learning approach to generate rules for process fault diagnosis. J Chem Eng Jpn. 2004;37:691–7. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sperry L. Consultation skills: individual and organizational diagnosis. Individual Psychol. 1994;50:359–71. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stahl DA. Subacute care: a six-box model. Nurs Manage. 1997;28:18–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CS, Chng CT. Dynamic process diagnosis via integrated neural networks. Comput Chem Eng. 1995;19(suppl S):747–52. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barrett T, Recor L. Needs assessment: a marketing application. Psychol Rep. 1983;52:702. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Caska BA, Kelley K, Christensen EW. Organizational Needs Assessment: Technology and Use. Vol. 82. Oxford: North-Holland; 1992. pp. 229–56. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVillaer M. Client-centered community needs assessment. Eval Prog Plann. 1990;13:211–9. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans NJ. Needs assessment methodology: a comparison of results. J Coll Stud Personnel. 1985;26:107–14. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoover JG. Needs assessment: implications for large scale planning of educational programs. J Instructional Psychol. 1977;4:34–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau JTF, Tsui HY, Li CK, Chung RWY, Chan MW, Molassiotis A. Needs assessment and social environment of people living with HIV/AIDS in Hong Kong. AIDS Care Psychol Socio Med Aspects AIDS/HIV. 2003;15:699–706. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001595186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy SR, Anderson EE, Issel LM, et al. Using multilevel, multisource needs assessment data for planning community interventions. Health Promotion Pract. 2004;5:59–68. doi: 10.1177/1524839903257688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monfils MK. Needs assessment and implementation of an employee assistance program: promoting a healthier work force. AAOHN J. 1995;43:263–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy JW. Qualitative methodology, hypothesis testing and the needs assessment. J Sociol Social Welfare. 1983;10:136–48. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murrell SA. Utilization of needs assessment for community decision-making. Am J Community Psychol. 1977;5:461–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simeone RS, Frank B, Aryan Z. Needs assessment in substance misuse: a comparison of approaches and case study. Int J Addictions. 1993;28:767–92. doi: 10.3109/10826089309062172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stabb SD. Needs Assessment Methodologies. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wiener RL, Wiley D, Huelsman T, et al. Needs assessment: combining qualitative interviews and concept mapping methodology. Eval Rev. 1994;18:227–40. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Witkin BR, Altschuld JW. Planning and Conducting Needs Assessments: A Practical Guide. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deming W. The New Economics for Industry, Government & Education. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Engineering Study; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juran JM, Blanton A, Godfrey AB, Hoogstoel RE, Schilling EG, editors. Juran's Quality Handbook. 5. McGraw Hill: New York; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogers E. Diffusion of Innovations. 4. New York: Free Press; 1962. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grol R. Improving the quality of medical care: building bridges among professional pride, payer profit, and patient satisfaction. JAMA. 2001;286:2578–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.20.2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bero LA, Roberto GR, Grimshaw JM, Harvey E, Oxman AD, Thomson MA. Getting research findings into practice—closing the gap between research and practice—an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the implementation of research findings. Br Med J. 1998;317:465–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7156.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hulscher M, Laurant M, Grol R. Process evaluation on quality improvement interventions. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12:40–6. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greco PJ, Eisenberg JM. Changing physicians' practices [see comment] New Engl J Med. 1993;329:1271–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310213291714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flottorp S, Havelsrud K, Oxman AD. Process evaluation of a cluster randomized trial of tailored interventions to implement guidelines in primary care—why is it so hard to change practice? Fam Pract. 2003;20:333–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmg316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paton SM. Four Days with W. Edwards Deming. Potomac, MD: The W. Edwards Deming Institute; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demakis JG, Lynn McQueen L, Kenneth W, Kizer KW, Feussner JR. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI): a collaboration between research and clinical practice. Med Care. 2000;38(suppl 1):I17–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burns CM, Vicente KJ. A participant-observer study of ergonomics in engineering design: how constraints drive design process. Appl Ergon. 2000;31:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(99)00017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burns CM, Vicente KJ, Christoffersen K, Pawlak WS. Towards viable, useful and usable human factors design guidance. Appl Ergon. 1997;28:311–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-6870(97)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]