Dendritic cells in the thymus contribute to T-regulatory cell induction (original) (raw)

Abstract

Central tolerance is established through negative selection of self-reactive thymocytes and the induction of T-regulatory cells (TRs). The role of thymic dendritic cells (TDCs) in these processes has not been clearly determined. In this study, we demonstrate that in vivo, TDCs not only play a role in negative selection but in the induction of TRs. TDCs include two conventional dendritic cell (DC) subtypes, CD8loSirpαhi/+ (CD8loSirpα+) and CD8hiSirpαlo/− (CD8loSirpα−), which have different origins. We found that the CD8hiSirpα+ DCs represent a conventional DC subset that originates from the blood and migrates into the thymus. Moreover, we show that the CD8loSirpα+ DCs demonstrate a superior capacity to induce TRs in vitro. Finally, using a thymic transplantation system, we demonstrate that the DCs in the periphery can migrate into the thymus, where they efficiently induce TR generation and negative selection.

Keywords: thymic selection, migratory dendritic cells, tolerance

Tolerance to self-antigens is established in the thymus. Developing thymocytes undergo stringent selection to eliminate self-reactivity (1). Developing T cells that recognize self-peptide with a sufficiently high affinity can encounter two fates: (i) deletion through negative selection or (ii) differentiation into T-regulatory cells (TRs). TRs express the transcription factor Foxp3 (2–4) and can suppress self-reactive T cells that have escaped negative selection (5, 6). During mouse ontogeny, TRs appear in the thymus 3 days after birth (7). Deficiency in TR development or function results in multiorgan autoimmunity (6).

A role for thymic dendritic cells (TDCs) in negative selection (8–12) and for thymic epithelial cells (TECs) in negative selection and TR induction has been demonstrated (9, 13–16). The role of dendritic cells (DCs) in TR generation in the thymus is unclear, however. Given the importance of DCs in the generation of peripherally induced TRs (17, 18), and in light of a recent study demonstrating the potential of human TDCs to induce TRs in vitro (19), the possible role of TDCs in TR induction in vivo needs careful dissection using mouse models.

In mouse thymus, three subsets of DCs have been identified. The plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC) and two conventional dendritic cell (cDC) subsets defined based on CD8α and Sirpα expression: the CD8loSirpαhi/+ cDCs (≈30% of cDCs, Sirpα+ TcDCs hereafter) and the CD8hiSirpαlo/− cDCs (≈70% of cDCs, Sirpα− TcDCs hereafter) (20, 21). Sirpα− TcDCs develop from intrathymic lymphoid precursors (22, 23). The origin of Sirpα+ TcDCs is less clear, although one study demonstrated that the CD8loCD11b+ cDCs (equivalent to Sirpα+ cDCs) migrate into the thymus from the periphery (24). The role of the individual TDC subsets in T-cell selection is yet to be determined.

In addition to the contribution of medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) to TR generation (16), in this study, we demonstrate that TDCs make a significant contribution to TR induction as well as to negative selection. This was established in vivo using two bone marrow (BM) chimeric mouse models in which the hemopoietic-derived compartment was impaired in antigen presentation (MHC class II [MHCII]−/−) or T-cell activation (B7−/−). Using an in vitro culture system, we established that the Sirpα+ TcDCs played the major role in TR induction when compared with other DC subtypes. This functional capacity of the Sirpα+ TcDCs correlates with a unique set of properties, particularly their maturity, their chemokine production, and their migratory origin. These findings suggest that a subset of TDCs migrating from the periphery makes a specialized contribution to TR induction in the thymus.

Results

TDCs Contribute to TR Induction and Negative Selection In Vivo.

To dissect the contribution of DCs from that of mTECs in the induction of TRs, two different in vivo systems were used. In the first, irradiated C57BL/6 (B6) WT CD45.1 recipients were reconstituted with BM from MHCII−/− or B6 WT (CD45.2) mice. In MHCII−/− BM chimeras, the host epithelial cells can still present antigen via MHCII, whereas the BM-derived cells, including TDCs, cannot. In the second system, irradiated CD45.1 recipients were reconstituted with B7−/− BM (lacking CD80 and CD86) or WT BM for controls. Because expression of MHCII and costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 is essential for the induction of thymic-derived TRs (5, 14, 15, 19, 25, 26), these systems enabled us to discern the contribution of DCs to TR induction.

Because some DCs are radioresistant, it was important to establish whether TDCs in the chimeras were all of donor origin (27, 28). Staining the TDC-enriched light density cell fraction for donor-derived DCs 6 weeks after BM reconstitution demonstrated that >98% of DCs were of donor origin (MHCII−), indicating effective elimination of host DCs (Fig. 1A). The TDCs from the MHCII−/− BM chimeras did not express MHCII (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, both cDC subsets were observed in similar proportions and number in WT and MHCII−/− chimeras (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

MHCII+ DCs contribute to negative selection and TR induction. (A) The light density fraction of cells from the thymus of WT and MHCII−/− BM chimeras was analyzed to determine the % of donor-derived DCs. More than 98% of CD11c+ cells were CD45.2+ donor-derived DCs in both BM chimera groups. (B) MHCII expression on CD11c+ TDCs in WT (black line) and MHCII−/− (gray line) chimeras. (C) The % of double-negative, double-positive, CD4+, and CD8+ thymocytes (Upper) and CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ TRs (Lower). (D) The % and total number of CD4+ thymocytes in WT and MHCII−/− BM chimeras. (E) The % and total number of TRs in WT and MHCII−/− BM chimeras (n = 20–24 per group for D and E). (F) Suppressive activity of CD4+CD25+ thymocytes from MHCII−/− or WT chimeras. Data are the mean (error bars, ±SD) of triplicate cultures from one of two experiments. (G) The number of TRs (CD4+Foxp3+) in the thymus of B6 to B6, B6 to B7−/−, B7−/− to B6, and B7−/− to B7−/− BM chimeras was analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are the mean of three independent experiments (error bars, ±SD) (n = 68 for G). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001; ***, P < 0.0001.

To assess the effect on thymocyte development in mice lacking MHCII on DCs, the proportion and total numbers of the individual donor-derived thymocyte populations were determined (Fig. 1 C–E). Total thymic cellularity was comparable between the MHCII−/− and WT BM chimeras [supporting information (SI) Table S1], and the numbers of CD4−CD8− double-negative, CD4+CD8+ double-positive, and CD8+CD4− (CD8+ hereafter) T-cell populations were not significantly different between the two groups (Table S1). There was a 20% increase in the number of CD4+CD8− (CD4+ hereafter) thymocytes in the MHCII−/− BM chimeras, however, suggesting that there was incomplete negative selection (Fig. 1D). Syngeneic mixed leukocyte reaction assays confirmed that the CD4+ thymocytes contained auto-reactive T cells (data not shown). Concomitant with this increase was a statistically significant 30% decrease in the number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ TRs (P = 0.008) (Fig. 1E).

To test the function of the TRs in the WT and MHCII−/− chimeras, they were sorted and used in an in vitro TR suppression assay. The TRs from both groups were functional (Fig. 1F).

In the second BM chimeric system, B7−/− mice were used. Initially, it was established that B7−/− mice have a deficiency in the proportion of TRs that equated to a 94% decrease (Fig. S1_A_). To establish if this was attributable to cells in the hemopoietic or epithelial cell compartment, four cohorts of chimeras were set up. CD45.1 WT or CD45.1 B7−/− mice were reconstituted with CD45.2 WT or B7−/− BM and analyzed for TR development 8 weeks after reconstitution. Total thymic cellularity did not differ between the four cohorts (data not shown). There was a 50% decrease in the number of thymic TRs in the B7−/− to WT chimeric mice, however (Fig. 1G; Fig. S1_B_).

Overall, these results suggest a nonredundant role for TDCs in the induction of thymic TRs and in the negative selection of self-reactive CD4+ thymocytes.

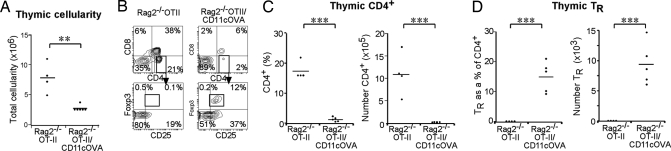

DCs Induce Antigen-Specific TRs and Negative Selection In Vivo.

TR induction and negative selection of self-reactive thymocytes require self-peptide presentation on MHCII via an antigen-presenting cell (14, 15). To address TR induction by DCs in an antigen-specific system, Rag2−/− OTII T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic (tg) mice (which lack OVA-specific TRs because of the absence of the OVA antigen) were crossed with CD11cOVA tg mice (membrane-bound OVA expressed under the CD11c promoter). In these Rag2−/−OTII/CD11cOVA (Rag2−/−O/OVA) double-tg mice, OVA is expressed on CD11c+ TDCs and can influence the development of CD4+ T cells that express the OVA-specific TCR (29). To follow development of newly formed thymocytes from the double-tg BM cells, irradiated WT CD45.1 recipients were reconstituted with the BM of CD45.2 Rag2−/−O/OVA mice or Rag2−/−OTII mice for controls. Thymocytes were analyzed by flow cytometry 6 weeks later. Total cellularity of the Rag2−/−O/OVA BM chimeric thymuses was reduced compared with controls (Fig. 2A). The presentation of OVA by DCs in Rag2−/−O/OVA BM chimeric mice led to the deletion of the majority of OTII+CD4+ cells, as seen by a >90% reduction in the total number of CD45.2+CD4+Vα2+ OTII thymocytes compared with controls (Fig. 2 B and C). Furthermore, there was a clear induction of OTII TRs in the thymus of Rag2−/−O/OVA BM chimeras (mean 15 ± 2% of OTII+CD4+ cells) compared with the controls (0.1% of OTII+CD4+ thymocytes). This represented a greater than 150-fold increase in TR numbers in the thymus of Rag2−/−O/OVA BM chimeras compared with controls (Fig. 2 B and D).

Fig. 2.

OVA expressing DCs induce OTII TRs and deletion of OTII CD4+ T cells. Irradiated WT CD45.1 mice were reconstituted with double-tg Rag2−/−OTII/CD11cOVA (Rag2−/−O/OVA) BM or Rag2−/−OTII BM as a control (n = 4–5 per group). (A) Total thymic cellularity of Rag2−/−O/OVA and control BM chimeras. (B) CD45.2+Vα2+ thymocytes were gated, and the % of CD4+ and CD8+ thymocytes was determined. To assess TR induction, CD4+ OTII+ thymocytes were gated for and expression of CD25 and Foxp3 was determined. The % and number of OTII+ CD4+ thymocytes (C) and the % and number of TRs (D) in Rag2−/−O/OVA and control BM chimeras.

Overall, these results demonstrate that DCs are capable of TR induction and negative selection in an antigen-specific manner.

Sirpα+ TcDCs Are More Mature in Surface Phenotype Than the Sirpα− TcDCs.

Because TDCs were involved in TR generation and negative selection, we investigated the contribution of the TDC subtypes to these processes. We compared TDCs for expression of MHCII and costimulatory molecules, because these are important in TR induction and negative selection (19, 30–34). We then compared the TDCs with their splenic DC (SDC) equivalents. TDCs and SDCs were segregated into pDCs and cDCs, which could be further segregated as Sirpα+CD8lo and Sirpα−CD8+ cDCs (21) (Fig. 3A). Strikingly, the Sirpα+ TcDCs expressed higher levels of MHCII and CD86 and slightly increased levels of the activation marker CD69 and the costimulatory molecules CD40 and CD80 compared with Sirpα− TcDCs (Fig. 3B). This difference was not observed between the DC subsets in the spleen, where both cDC subsets expressed comparable levels of these markers (refs. 35, 36; Fig. 3B). Nor was there a difference in expression of these molecules in thymic versus splenic pDCs (Fig. 3C). Thus, in the steady state, Sirpα+ TcDCs are phenotypically more “mature” than other TDC subtypes.

Fig. 3.

Sirpα+ TcDCs are more mature and efficiently induce TRs in vitro. (A) Enriched TDCs and SDCs were segregated into pDCs (CD11cintCD45RA+) and cDCs (CD11c+CD45RA−) and further segregated into CD8loSirpα+ and CD8hiSirp− cDCs. Thymic and splenic Sirpα+ and Sirpα− cDCs (B) and thymic and splenic pDCs (C) were analyzed for the expression of costimulatory molecules, CD69, and MHCII. (D) TR (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) induction by TDC subsets in the cocultures of TDCs and CD4+CD25− thymocytes for 5 days. Data shown are representative of six experiments. (E) The number of TRs induced was determined by flow cytometric analysis of the cultured cells of D using calibration beads (n = 6) (error bars, ±SD). (F) Suppressive capacity of TRs induced in cultures by Sirpα+ TcDCs. _In vitro_–derived TRs were sorted as CD4+CD25+CD62L+ and subject to a suppression assay as per Fig. 1F. The number of proliferating CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25− T cells was determined 3 days later (n = 2).

Sirpα+ TcDCs Are More Efficient at Inducing Functional TRs In Vitro.

To compare the capacity of each TcDC subset to induce TRs, sorted TDC subsets were cocultured with syngeneic CD4+CD8−CD25− thymocytes (which contain TR precursors) for 5 days. To maintain T-cell survival, an optimal level of IL-7 was added (37). The number of TRs that developed in these cultures was enumerated. The Sirpα+ TcDCs were the most efficient at inducing TRs, as shown by the higher number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells in the cultures (Fig. 3 D and E). In the cultures containing Sirpα+ TcDCs, there was also some level of T-cell activation, as evidenced by a population of CD4+CD25intFoxp3− (Fig. 3D and data not shown). This T-cell activation was accompanied by T-cell proliferation and a higher total number of T cells within the cultures (Fig. S2_A_). Given that the proportion of TRs induced in Sirpα+ TcDC cocultures (14 ± 5%) was also significantly higher compared with Sirpα− TcDC cocultures (9 ± 1%) (Fig. 3D), it was clear that the increased number of TRs could not be attributable solely to a higher absolute number of T cells generated. Furthermore, we determined that the TR induction observed was attributable to de novo generation and not to proliferation of preexisting CD4+CD25−Foxp3+ cells within the starting population of thymocytes by using Foxp3-GFP mice to gate out CD4+CD25−Foxp3+ cells (Fig. S2_B_).

TR generation in vitro was thymus specific. When TDCs were cultured with splenic CD4+CD25− naïve T cells rather than thymic CD4+CD25− T cells, no TR induction was observed (Fig. S2_C_), even in the presence of T-cell activation and proliferation (Fig. S2_D_). Conversely, when SDCs were cocultured with thymic CD4+CD25− T cells, few TRs were generated (data not shown).

To test the function of _in vitro_–derived TRs, TRs were sorted as CD4+CD25+CD62L+ cells and used in a TR suppression assay. CD62L was included as a marker to exclude activated T cells. In vitro derived TRs were able to suppress T-cell proliferation (Fig. 3F).

BM-derived cells that express MHCII within the thymus include B cells and macrophages. To exclude the possibility of TR induction by those cells, the same coculture method was used. We demonstrated that the TR induction capacities of both of these cell types were negligible (Fig. S2_E_).

Sirpα+ TcDCs Produce Chemokines and Attract CD4+ Thymocytes.

The chemokine-mediated migration of developing thymocytes through the thymus ensures their interaction with the appropriate thymic stromal cells. We examined chemokine production as a factor that may explain the effectiveness of the Sirpα+ TcDCs in inducing TRs. The expression of the genes encoding six chemokines known to be involved in thymocyte differentiation was examined by real-time (RT) PCR, comparing the TDC and SDC subsets, macrophages, and thymic mTECs.

The mTECs expressed significantly higher levels of CCL19, CCL21, and CCL25, higher than the DC subsets (Fig. S3_A_). In contrast, CCL17 and CCL22 were expressed at very high levels only by the Sirpα+ TcDCs (Fig. S3_A_). The expression of CCL22 by the Sirpα+ TcDCs was confirmed at the protein level by intracellular chemokine staining (Fig. S3_B_).

CCL17 and CCL22 both bind to CCR4. Using RT-PCR, we found that the CD4+ thymocytes expressed the highest levels of CCR4 (Fig. S3_C_), a finding consistent with other studies (38). To test whether the DC-expressed chemokines were chemotactic for CD4+ thymocytes, migration assays were performed. Sorted TDC and SDC subsets were cultured alone for 3 h. The supernatants were then used as a source of chemotactins for CD4+ thymocytes, seeded in transwells, and incubated for 2 h. The supernatants from the Sirpα+ TcDC cultures showed the greatest capacity to attract CD4+ thymocytes (Fig. S3_D_). Thus, the Sirpα+ TcDCs, through their chemokine production, have a special capacity to attract newly formed CD4+ T cells.

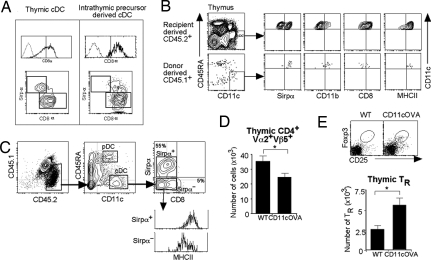

CD11c+Sirpα+CD11b+ cDCs Are Found in Blood and Migrate into the Thymus.

A number of observations have led to the suggestion that the TDC subsets have different developmental origins, with a major proportion of the TcDCs being derived from an early intrathymic precursor (24, 39). To test the origin of each TcDC, the earliest intrathymic precursors (Lineage−Thy-1loc-kit+) that have DC potential were transferred intrathymically into sublethally irradiated CD45.1 recipient mice. DC generation was analyzed 2 weeks after transfer. The cDCs that developed from the intrathymic precursors were mainly CD8+Sirpα− (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Sirpα+ TcDCs originate from peripheral blood and can migrate into the thymus. (A) DC generation from purified Lineage−Thy-1loc-kit+ intrathymic precursors (CD45.2) was analyzed 2 weeks after precursor transfer. The intrathymic precursor-derived cDCs were mainly CD8+Sirpα− (Right). A representative contour plot of the normal TcDC subsets is shown (Left) for comparison. (B) White blood cells (20 × 106) from CD45.1 mice were transferred i.v. into nonirradiated CD45.2 recipients. The phenotype of donor-derived cells in the thymus of recipients was determined 3 days later by gating for CD45.1+CD11c+CD45RAlo cDCs. Expression of Sirpα, CD11b, CD8, and MHCII was determined on this population. (C–E) Thymic lobes from OTII tg CD45.2+ mice crossed to CD45.1+ WT mice were grafted under the kidney capsule of CD45.2+ CD11cOVA tg or WT recipients. (C) The phenotype of recipient-derived CD45.2+CD45.1− DCs in the grafted thymic lobes from WT and CD11cOVA tg mice was determined. The recipient CD45.2+CD45.1−CD11c+CD45RA− cDCs were gated for, and the expression of CD8 and Sirpα was determined. The level of expression of MHCII was determined on Sirpα− and Sirpα+ cDCs. (D) The total number of CD45.1+CD4+Vα2+Vβ5+ cells (OTII) was calculated in OTII lobes grafted into WT or CD11cOVA tg recipients. Data are the mean of three independent experiments (error bars, ±SD) (n = 11–21). *, P < 0.05. (E) CD45.1+CD4+Vα2+Vβ5+ cells in the OTII lobes from WT and CD11cOVA tg recipients (as in D) were further analyzed for CD25 and Foxp3 expression. The total number of CD45.1+CD4+Vα2+Vβ5+CD25+Foxp3+ TRs was calculated. Data are the mean of three independent experiments (error bars, ±SD) (n = 11–21). *, P < 0.05.

In contrast, the CD8−CD11b+ TDC subset has been shown to migrate in parabiotic mice from the circulation into the thymus of the conjoined mouse (24). To determine whether the Sirpα+ TcDCs correspond to this population, the CD11c+ DCs within mouse blood were characterized. Total peripheral blood mononuclear cells were enriched for DCs. The preparation was then stained for DC markers. Gating on CD11c+ cells revealed that more than 70% of the blood DCs were Sirpα+CD11b+ (Fig. S4). Among the blood DCs, 25% expressed high levels of MHCII, indicating that immature and mature DCs were present in mouse blood.

To determine whether these blood DCs migrate to the thymus, white blood cells from CD45.1 mice were transferred i.v. into nonirradiated CD45.2 recipients and the phenotype of donor-derived cells in the recipient thymus was determined 3 days later. Donor-derived cells made up 0.1% of total cells in the recipient thymus, and of these, 10% were CD11c+CD45RA− cDCs. These cDCs were all Sirpα+CD11b+CD8loMHCIIhi (Fig. 4B), correlating with DCs found circulating in the blood.

Impact of Migrating DCs on T-Cell Development.

To determine the impact of circulating DCs on thymic T-cell selection, day 1 neonatal thymic lobes from CD45.1/OTII tg mice were grafted under the kidney capsule of recipient CD45.2 WT or CD45.2 CD11cOVA tg mice. This system allows recipient DCs to migrate into the grafted thymic lobes via the blood. Therefore, the effects of peripherally derived CD45.2 CD11cOVA migrating DCs on OTII T-cell development in the grafted lobes could be assessed. The kinetics of DC migration were determined. At day 7, before the recipient BM progenitors had contributed to the TDC population, the DCs entering the thymic lobes were predominantly the Sirpα+ cDCs (80 ± 5%; data not shown). We therefore waited a further 3–5 days to see the effects of these incoming DCs on T-cell development. Thymic lobes were removed 10–12 days after transplantation, and the phenotype of the incoming CD45.2+ DCs and the resident CD45.1+ OTII T cells was studied.

At day 10, DCs in the grafted thymic lobes were analyzed for DC markers to assess the phenotype of the host-derived CD45.2+ migrating DCs. Of these CD11c+ cells, 54 ± 6% were mature MHCIIhi CD8−Sirpα+ cDCs, 4 ± 1% were mature CD8+Sirpα− cDCs, and the remaining were MHCIIlo/int CD8−Sirpα−, the precursors of CD8+Sirpα− cDCs (Fig. 4C). The latter two populations represented newly formed cells derived from recipient BM progenitors that had seeded the thymic grafts.

Thymocyte populations were analyzed by flow cytometry. The number of CD45.1+OTII+CD4+Vα2+Vβ5+ T cells was reduced in lobes grafted into CD11cOVA tg mice compared with controls (Fig. 4D), whereas the number of CD45.1+ Vα2−Vβ5−CD4+ was similar in both groups (data not shown), suggesting that antigen-specific negative selection of OTII+ T cells was occurring. In addition, a more than twofold increase in the number of OTII+ Foxp3+ TRs was seen in the lobes grafted into CD11cOVA tg mice compared with controls (Fig. 4E). Together, these results indicate that DCs migrating into the thymus from the periphery can induce negative selection and antigen-specific TR development.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates a role for mouse TDCs in TR differentiation as well as negative selection. In the absence of a MHCII-expressing hemopoietic compartment, we found a 30% reduction in the total number of polyclonal TRs and an increase in the number of self-reactive CD4 T cells in the thymus. This demonstrates that in addition to mTECs (16, 40), BM-derived cells make a significant contribution to TR generation and negative selection of CD4 T cells in a steady-state mouse. In addition, a 50% reduction in TR numbers was observed when the hemopoietic compartment lacked expression of CD80 and CD86. Although these BM chimeras indicated that a BM-derived cell was important for TR induction, the in vitro coculture system indicated that only TDCs, and not B cells and macrophages, were efficient in inducing TRs. Thus, taken together, it appears that TDCs are the major hemopoietic cells that contribute significantly to TR generation and negative selection of CD4 T cells in vivo. Previous studies have discounted a nonredundant role for DCs in TR induction (41, 42). The irradiation protocol used (850–900 rad), which may not be sufficient to completely ablate host-derived cells, coupled with the later time point for analysis (8–10 weeks), may have contributed to these results, however. Mice with reduced thymic cellularity and a profound increase in CD4+ thymocyte cell numbers were observed in previous reports (41). We also see similar results in MHCII−/− BM chimeras at later time points. These mice have reduced thymic cellularity and show immune cell infiltration into organs—an initial sign of autoimmunity (data not shown). At this stage, the massive accumulation of autoreactive CD4+ T cells in the thymus has masked the changes in TR numbers.

Apart from the issue of their quantitative contribution to the total TR population, our results now demonstrate that TDCs can induce Ag-specific TR.

Three types of DCs are found in the mouse thymus (pDCs, Sirpα−CD8+ TcDCs, and Sirpα+CD8− TcDCs), and these have counterparts in the human thymus (43). We show that the minor Sirpα+ TcDC subset is much more efficient than the other DCs at polyclonal TR induction in vitro.

Why would the Sirpα+ TcDCs be more efficient in TR generation? First, the Sirpα+ TcDCs are more mature, in terms of expression of MHCII and costimulatory molecule, than the other TDCs, consistent with the phenotype of migratory DCs. This may enable them to interact more efficiently with the CD4+ thymocytes. Second, the Sirpα+ cDCs are more efficient at presentation of antigens on MHCII than the CD8+ cDCs (44–46). Finally, we found that the Sirpα+ TcDCs express high levels of CCL17 and CCL22, and this may facilitate an interaction with the CD4+ thymocytes expressing high levels of CCR4. In a cell migration assay, CD4+ thymocytes preferentially migrated toward supernatants from the Sirpα+ TcDCs. This provides a mechanism by which rare antigen-specific thymocytes can encounter their cognate antigen with a higher frequency.

Previous studies showed that migratory DC can induce negative selection of T cells specific for a peripherally expressed antigen (10). We now add to this picture by demonstrating that Sirpα+ cDCs or their immediate precursors present in blood migrate into the thymus and induce both negative selection and TR development.

Would this process be detrimental to the host during a viral infection? Viral antigens in the periphery ferried to the thymus may induce TRs, which could induce tolerance to the virus and potentially jeopardize a memory response. It is possible that thymic homing receptors or lymphoid egress receptors are down-regulated in DCs that have been activated by virus infection. Indeed, activated T cells down-regulate the egress receptor sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor-1, leading to retention of T cells in the lymphoid tissues (47). Whether this also occurs in activated DCs would be an interesting question to address in future studies.

In summary, we demonstrate that thymic DCs contribute to TR induction in vivo. More significantly, we show that peripheral DCs can migrate into the thymus, where they induce the development of TRs and the deletion of self-reactive CD4+ thymocytes. Based on these observations, we propose a mechanism by which central tolerance to peripherally expressed antigens is induced by migrating DCs, a mechanism additional to the ectopic expression of peripheral antigens by mTECs.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

All mice were bred under specific pathogen-free conditions. B7−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory and maintained in the University Laboratory Animal Research Facility at the University of Michigan. All other mice were obtained from The Walter and Eliza Hall Institute animal breeding facility. C57BL/6 (B6) mice 6–8 weeks of age were used for isolation of DCs and thymocytes. B6 CD45.1 mice 10 weeks of age were used as BM recipients. The mouse strains used included OTII tg (CD4+ T cells expressing the TCR specific for MHCII-restricted Ova peptide) (48) on a B6, CD45.1, or Rag2−/− background; IA/IA−/− (MHCII−/−) (49); B7−/− (50); and CD11cOVA tg mice that express membrane-bound ovalbumin (amino acids 323–339) under control of the CD11c promoter (29, 51).

BM Chimeras.

CD45.1 recipient mice were lethally irradiated with two doses of 5.5 Gy (3 h apart) and then received 5 × 106 CD45.2 donor BM cells i.v. from B6 or MHCII−/− mice or from Rag2−/−OTII/CD11cOVA double-tg mice. For B7−/− chimeras, CD45.1 recipient mice were lethally irradiated with 8.0 Gy of total body irradiation. A total of 5 × 106 T-cell depleted B6 WT or B7−/− donor BM cells were injected i.v. into the recipients the next day. Chimeras were analyzed by flow cytometry 6–8 weeks after reconstitution.

Antibodies.

Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

Isolation of DCs.

Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

Isolation of Thymocytes.

Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

Carboxyfluorescein Succinimidyl Ester Labeling.

Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

Isolation of Thymic B Cells, Macrophages, and mTECs.

Details can be found in SI Experimental Procedures.

TR Suppression Assay.

Details can be found in Supplementary Experimental Procedures.

Generation of TRs In Vitro.

In vitro TR induction assays were performed in triplicate in a round-bottom 96-well plate with 1 × 104 sorted thymic or splenic DC subsets from CD45.2 mice and 2 × 104 sorted CD4+CD25− thymocytes from CD45.1 mice, cultured together with an optimal concentration of IL-7 for 5 days. TRs were assessed by staining for CD45.1 (A201.1), CD4, CD25, and Foxp3. When GFP-Foxp3 mice were used as the CD4+ thymocyte source, thymocytes were sorted as CD4+CD25−Foxp3− (excluding all Foxp3+ cells). IL-7 used was from the culture supernatant of J558L cells transfected with the murine IL-7 cDNA in the BMG neo vector (55). To determine the optimal concentration of the IL-7 supernatant, the supernatant was titrated on IL-7–dependent pro-B cells (37).

Quantitative PCR.

Quantitative PCR was performed for chemokine gene expression by DC subsets as previously described (56). Further details can be found in Supplementary Experimental Procedures.

Cell Migration Assay.

Sorted TDC and SDC subsets (5 × 105 in 600 μl) were cultured in a 24-well plate for 3 h. The supernatant was removed and placed in the base of transwell chambers (5.0-μM pore size; COSTAR). Sorted CD4+CD25− thymocytes (2 × 105) were placed in the top of the chamber and allowed to migrate for 2 h at 37 °C. The number of cells that had migrated was enumerated using fixed numbers of beads as a calibration standard.

In Vivo DC Migration Assay.

Details can be found in Supplementary Experimental Procedures.

Staining Blood DCs.

Details can be found in Supplementary Experimental Procedures.

Thymic Grafting.

Thymic lobes from 1-day-old donor mice were grafted under the kidney capsule of anesthetized 8-week-old recipient mice using a procedure described elsewhere (57). At specified times postgrafting, grafted thymic lobes were recovered and processed individually. Thymic lobes were digested in collagenase/DNase and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical significance was assessed by the two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. Differences with P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments.

We thank T. Berketa and J. Carneli for animal husbandry; C. Young, C. Tarlinton, V. Milovac, J. Garbe, T. McLeod-Dryden, and S. Fung for assistance with flow cytometric sorting and analysis; M. Bradtke and D. Vremec for technical assistance; and I. Caminschi, J. Miller, J. Villandangos, and W. Heath for discussions. L. Wu and K. Shortman were supported by a grant from the Australian Stem Cell Centre and a grant from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Palmer E. Negative selection—clearing out the bad apples from the T-cell repertoire. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:383–391. doi: 10.1038/nri1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science (New York, NY) 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:337–342. doi: 10.1038/ni909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan MS, et al. Thymic selection of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells induced by an agonist self-peptide. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:301–306. doi: 10.1038/86302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontenot JD, Dooley JL, Farr AG, Rudensky AY. Developmental regulation of Foxp3 expression during ontogeny. J Exp Med. 2005;202:901–906. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao EK, Lo D, Sprent J. Strong T cell tolerance in parent—F1 bone marrow chimeras prepared with supralethal irradiation. Evidence for clonal deletion and anergy. J Exp Med. 1990;171:1101–1121. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallegos AM, Bevan MJ. Central tolerance to tissue-specific antigens mediated by direct and indirect antigen presentation. J Exp Med. 2004;200:1039–1049. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonasio R, et al. Clonal deletion of thymocytes by circulating dendritic cells homing to the thymus. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brocker T. Survival of mature CD4 T lymphocytes is dependent on major histocompatibility complex class II-expressing dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1223–1232. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.8.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Meerwijk JP, et al. Quantitative impact of thymic clonal deletion on the T cell repertoire. J Exp Med. 1997;185:377–383. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Webb SR, Sprent J. Tolerogenicity of thymic epithelium. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2525–2528. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bensinger SJ, Bandeira A, Jordan MS, Caton AJ, Laufer TM. Major histocompatibility complex class II-positive cortical epithelium mediates the selection of CD4(+)25(+) immunoregulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194:427–438. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Apostolou I, Sarukhan A, Klein L, von Boehmer H. Origin of regulatory T cells with known specificity for antigen. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:756–763. doi: 10.1038/ni816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aschenbrenner K, et al. Selection of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells specific for self antigen expressed and presented by Aire+ medullary thymic epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:351–358. doi: 10.1038/ni1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coombes JL, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-β and retinoic acid dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mucida D, et al. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science (New York, NY) 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watanabe N, et al. Hassall's corpuscles instruct dendritic cells to induce CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in human thymus. Nature. 2005;436:1181–1185. doi: 10.1038/nature03886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vremec D, Pooley J, Hochrein H, Wu L, Shortman K. CD4 and CD8 expression by dendritic cell subtypes in mouse thymus and spleen. J Immunol. 2000;164:2978–2986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lahoud MH, et al. Signal regulatory protein molecules are differentially expressed by CD8-dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2006;177:372–382. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu L, Li CL, Shortman K. Thymic dendritic cell precursors: relationship to the T lymphocyte lineage and phenotype of the dendritic cell progeny. J Exp Med. 1996;184:903–911. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ardavin C, Wu L, Li CL, Shortman K. Thymic dendritic cells and T cells develop simultaneously in the thymus from a common precursor population. Nature. 1993;362:761–763. doi: 10.1038/362761a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Donskoy E, Goldschneider I. Two developmentally distinct populations of dendritic cells inhabit the adult mouse thymus: demonstration by differential importation of hematogenous precursors under steady state conditions. J Immunol. 2003;170:3514–3521. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontenot JD, et al. Regulatory T cell lineage specification by the forkhead transcription factor foxp3. Immunity. 2005;22:329–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bochtler P, Wahl C, Schirmbeck R, Reimann J. Functional adaptive CD4 foxp3 T cells develop in MHC class II-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2006;177:8307–8314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bogunovic M, et al. Identification of a radio-resistant and cycling dermal dendritic cell population in mice and men. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2627–2638. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Merad M, et al. Langerhans cells renew in the skin throughout life under steady-state conditions. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/ni852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steptoe RJ, et al. Cognate CD4+ help elicited by resting dendritic cells does not impair the induction of peripheral tolerance in CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:2094–2103. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takeda I, et al. Distinct roles for the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction in regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3580–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salomon B, et al. B7/CD28 costimulation is essential for the homeostasis of the CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells that control autoimmune diabetes. Immunity. 2000;12:431–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80195-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takahashi T, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Q, et al. Cutting edge: CD28 controls peripheral homeostasis of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:3348–3352. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.7.3348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumanogoh A, et al. Increased T cell autoreactivity in the absence of CD40-CD40 ligand interactions: A role of CD40 in regulatory T cell development. J Immunol. 2001;166:353–360. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson NS, et al. Most lymphoid organ dendritic cell types are phenotypically and functionally immature. Blood. 2003;102:2187–2194. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson NS, Villadangos JA. Lymphoid organ dendritic cells: Beyond the Langerhans cells paradigm. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1711.2004.01216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nutt SL, Urbanek P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. Essential functions of Pax5 (BSAP) in pro-B cell development: Difference between fetal and adult B lymphopoiesis and reduced V-to-DJ recombination at the IgH locus. Genes Dev. 1997;11:476–491. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chantry D, et al. Macrophage-derived chemokine is localized to thymic medullary epithelial cells and is a chemoattractant for CD3(+), CD4(+), CD8(low) thymocytes. Blood. 1999;94:1890–1898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu L, et al. Mouse thymus dendritic cells: Kinetics of development and changes in surface markers during maturation. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:418–425. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klein L, Roettinger B, Kyewski B. Sampling of complementing self-antigen pools by thymic stromal cells maximizes the scope of central T cell tolerance. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2476–2486. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200108)31:8<2476::aid-immu2476>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liston A, et al. Differentiation of regulatory Foxp3+ T cells in the thymic cortex. PNAS. 2008;105:11903–11908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801506105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ribot J, Romagnoli P, van Meerwijk JP. Agonist ligands expressed by thymic epithelium enhance positive selection of regulatory T lymphocytes from precursors with a normally diverse TCR repertoire. J Immunol. 2006;177:1101–1107. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.2.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vandenabeele S, Hochrein H, Mavaddat N, Winkel K, Shortman K. Human thymus contains 2 distinct dendritic cell populations. Blood. 2001;97:1733–1741. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudziak D, et al. Differential antigen processing by dendritic cell subsets in vivo. Science (New York, NY) 2007;315:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.1136080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pooley JL, Heath WR, Shortman K. Cutting edge: Intravenous soluble antigen is presented to CD4 T cells by CD8- dendritic cells, but cross-presented to CD8 T cells by CD8+ dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2001;166:5327–5330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schnorrer P, et al. The dominant role of CD8+ dendritic cells in cross-presentation is not dictated by antigen capture. PNAS. 2006;103:10729–10734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601956103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shiow LR, et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cosgrove D, et al. Mice lacking MHC class II molecules. Cell. 1991;66:1051–1066. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Borriello F, et al. B7–1 and B7–2 have overlapping, critical roles in immunoglobulin class switching and germinal center formation. Immunity. 1997;6:303–313. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80333-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brocker T, Riedinger M, Karjalainen K. Targeted expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecules demonstrates that dendritic cells can induce negative but not positive selection of thymocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;185:541–550. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vremec D, et al. The surface phenotype of dendritic cells purified from mouse thymus and spleen: Investigation of the CD8 expression by a subpopulation of dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1992;176:47–58. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vremec D, Shortman K. Dendritic cell subtypes in mouse lymphoid organs: Cross-correlation of surface markers, changes with incubation, and differences among thymus, spleen, and lymph nodes. J Immunol. 1997;159:565–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray DH, Chidgey AP, Boyd RL. Analysis of thymic stromal cell populations using flow cytometry. J Immunol Methods. 2002;260:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(01)00493-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winkler TH, Melchers F, Rolink AG. Interleukin-3 and interleukin-7 are alternative growth factors for the same B-cell precursors in the mouse. Blood. 1995;85:2045–2051. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Proietto AI, et al. Differential production of inflammatory chemokines by murine dendritic cell subsets. Immunobiology. 2004;209:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berzins SP, Boyd RL, Miller JF. The role of the thymus and recent thymic migrants in the maintenance of the adult peripheral lymphocyte pool. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1839–1848. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.11.1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information