Hierarchical maintenance of MLL myeloid leukemia stem cells employs a transcriptional program shared with embryonic rather than adult stem cells (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2010 Feb 7.

Published in final edited form as: Cell Stem Cell. 2009 Feb 6;4(2):129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.015

Summary

The genetic programs that promote retention of self-renewing leukemia stem cells (LSCs) at the apex of cellular hierarchies in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are not known. In a mouse model of human AML, LSCs exhibit variable frequencies that correlate with the initiating MLL oncogene and are maintained in a self-renewing state by a transcriptional sub-program more akin to that of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) than adult stem cells. The transcription/chromatin regulatory factors Myb, Hmgb3 and Cbx5 are critical components of the program and suffice for _Hoxa/Meis_-independent immortalization of myeloid progenitors when co-expressed, establishing the cooperative and essential role of an ESC-like LSC maintenance program ancillary to the leukemia initiating MLL/Hox/Meis program. Enriched expression of LSC maintenance and ESC-like program genes in normal myeloid progenitors and poor prognosis human malignancies links the frequency of aberrantly self-renewing progenitor-like cancer stem cells to prognosis in human cancer.

Keywords: MLL, cancer stem cell, leukemia, transcriptional profile

Introduction

The cancer stem cell (CSC) model posits that many human malignancies consist of two functionally distinct cell types: (i) CSCs, which are self-renewing cells with the capacity to initiate, sustain and expand the disease, and (ii) non-self-renewing progeny cells, derived from CSCs through differentiation, which likely make up the bulk of the tumor and account for disease symptomatology (Jordan et al., 2006; Clarke et al., 2006). For malignancies to be cured, it may be necessary and sufficient to exclusively eliminate CSCs. Consequently, there is considerable interest in further understanding the biologic and molecular properties of these cells, by comparison with both their non-self-renewing downstream progeny and their normal adult stem cell counterparts.

CSCs (also called tumor-propagating or tumor-initiating cells) were first formally described in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) as rare cells that share an immunophenotype with normal hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) (Bonnet and Dick, 1997). This paradigm has recently been substantially revised based on two significant observations. First, in murine models of human leukemia induced by the MLL-AF9 oncogene, self-renewing leukemia stem cells (LSCs) may account for up to a quarter of cells within the leukemia clone and exhibit mature myeloid immunophenotypes (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006). A high frequency of LSCs was also observed in Sfpi -/-murine AMLs (Kelly et al., 2007). Secondly, protocols that enhance engraftment of human leukemia cells in xenogeneic transplant assays demonstrate the presence of LSCs in leukemia cell sub-populations previously considered to be devoid of them (Taussig et al., 2008).

Since LSCs may be more numerous and mature than originally proposed, the nature and generality of the hierarchical organization of malignancies has recently been questioned (Kelly et al., 2007). However, consistent with the CSC model, only a subset of AML cells have clonogenic potential in in vitro assays (Buick et al., 1977; Somervaille and Cleary, 2006), and human AML blast cells undergo differentiation in vivo to mature granulocytes (Fearon et al., 1986), as may murine LSCs initiated by MLL-AF9 (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006). To further elucidate the hierarchical disposition of AML, a major goal is to identify transcriptional programs, genes and pathways that specifically correlate with and promote the retention of LSCs within the self-renewing compartment of leukemias (Clarke et al., 2006). It is not known whether such LSC maintenance programs are synonymous with programs responsible for leukemia initiation, for example Hoxa/Meis in MLL leukemogenesis (Ayton and Cleary, 2003; Krivtsov et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2007). It is also not clear whether they share features with transcriptional programs expressed in adult or embryonic stem cells (ESCs) (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Wong et al., 2008), or whether there is a relationship with genes and pathways implicated in the function of AML stem cells such as NFκB, phosphatidylinositide-3-kinase, CTNNB1, Pten (reviewed in Jordan et al., 2006), Bmi1 (Lessard and Sauvageau, 2003) and Junb (Steidl et al., 2006).

To address these issues, we investigated the genetic determinants that maintain LSC frequencies and leukemia cell hierarchies using a mouse model that faithfully recapitulates many of the pathologic features of AML induced by chromosomal translocations of the MLL gene (Lavau et al., 1997; Somervaille and Cleary, 2006), which occur in about 5-10% of human AMLs (Look, 1997). Confirming recent speculation that CSC frequency may differ between distinct tumor types (Kelly et al., 2007; Adams et al., 2007; Kennedy et al., 2007), LSC frequency in AML was found to vary substantially according to the initiating MLL oncogene. This feature, and the observation that LSC frequency varies within the leukemia cell hierarchy, was used to derive a transcriptional program for LSC hierarchical maintenance. The program indicates that MLL LSCs are maintained in a self-renewing state by co-option of a transcriptional program that shares features with ESCs and is transiently expressed in normal myeloid precursors rather than HSCs or mature neutrophils. Furthermore, the shared transcriptional features of LSCs, ESCs, normal mid-myeloid lineage cells, and a diverse set of poor prognosis human malignancies supports the broader conclusion that CSCs may be aberrantly self-renewing downstream progenitor cells whose frequency in human malignant disease correlates with and dictates prognosis.

Results

Distinct molecular subtypes of MLL leukemia are associated with different LSC frequencies and leukemia cell hierarchies

LSC frequencies and leukemia cell hierarchies were characterized in cohorts of mice where AML had been initiated using MLL oncogenes (MLL-AF9, MLL-ENL, MLL-AF10, MLL-AF1p and MLL-GAS7) that function through distinct molecular mechanisms (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006; Lavau et al., 1997; Dimartino et al., 2002; So et al., 2003 (1) and (2)) (Supplemental Table 1). Relative LSC frequencies were assessed by determining AML colony forming cell (CFC) frequencies in the spleen and bone marrow (BM) of leukemic mice. AML CFCs are a surrogate measure for LSCs in both MLL-AF9 leukemia (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006) and other MLL leukemia molecular subtypes (Supplemental Figure 1), as shown by secondary transplantation of cells derived from singly isolated colonies. In leukemic mice where AML had been initiated by MLL-ENL or MLL-AF9, the frequencies of AML CFCs/LSCs in both spleen and BM were significantly higher than in mice where leukemia had been initiated by MLL-AF10, MLL-AF1p or MLL-GAS7 (Figure 1A and data not shown). Concordant with these data, approximately seven times as many MLL-AF1p leukemia cells were required to initiate secondary AML by comparison with MLL-ENL leukemia cells in limit dilution analyses (Figure 1B). FACS analyses showed that greater than 99.5% of BM cells in all leukemias expressed one or more myeloid-specific antigens, whereas less than 0.5% of cells were Lin- (Supplemental Table 2) demonstrating that LSCs in the different molecular subtypes of AML are predominantly myeloid Lin+ cells.

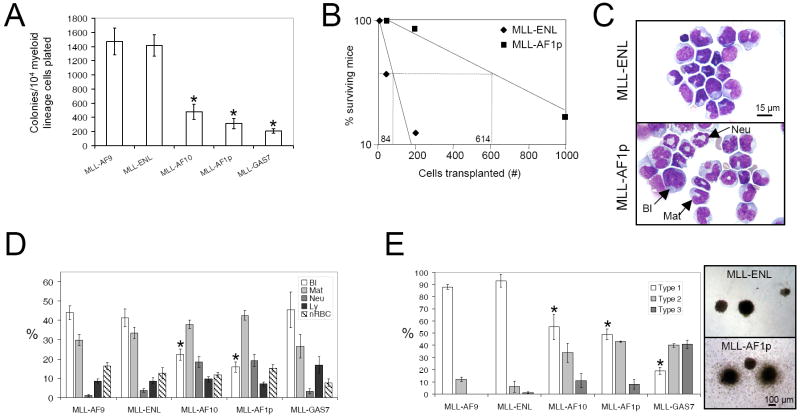

Figure 1. Variable LSC frequencies and cellular hierarchies in murine AMLs induced by different MLL oncogenes.

(A) Bar graph shows frequency of colony forming cells (CFCs) in the spleens of leukemic mice (mean ±SEM; n=7 leukemias for each fusion, except MLL-GAS7 where n=11; * represents p≤0.001 by comparison with MLL-AF9).

(B) Limit dilution analyses show the estimated number of secondarily transplanted leukemic MLL-ENL or MLL-AF1p splenocytes required to initiate AML in sub-lethally irradiated recipient mice (n=8 recipients for each cell dose). Mice were followed for 180 days, with the longest disease latencies being 66 days for MLL-ENL and 67 days for MLL-AF1p.

(C) In representative bone marrow cytospin images, MLL-AF1p initiated AML cells are more differentiated by comparison with MLL-ENL initiated AML cells. Scale bar applies to both images.

(D) Bar graph shows percentage cell type in spleen as determined by morphologic analysis of cytospin preparations (mean ±SEM; n=8-13 for each cohort; * represents p≤0.05 for blast cell percentage versus MLL-AF9). Bl, blast cell; Mat, maturing myelomonocytic cell; Neu, neutrophil; Ly, lymphocyte; nRBC, nucleated erythroid precursor cell.

(E) Bar graph shows proportion of myeloid leukemia colonies of each morphologic type (defined in Lavau et al., 1997) (mean ±SEM; n=3-5 separate leukemias for each fusion; * represents p<0.05 by comparison with MLL-AF9 for Type 1 colony frequency). Representative images are shown on the right. Scale bar applies to both images.

There was also a marked disparity in the hierarchical organization of the respective leukemias. Those initiated by MLL-AF10 or MLL-AF1p displayed extensive mature myeloid lineage differentiation (Figure 1C, D) that was part of the leukemia clone (Supplemental Figure 2), and were classified as either acute myeloproliferative disease-like myeloid leukemia or acute myelomonocytic leukemia according to the Bethesda criteria (Kogan et al., 2002). Conversely, leukemias initiated by MLL-AF9 or MLL-ENL showed less differentiation and most (16/18) were classified as acute monocytic leukemia (Supplemental Table 3). Consistent with this, their explanted colonies in CFC assays were significantly more “blast-like” (Type 1, Lavau et al., 1997) containing a higher proportion of cells displaying immature cytological and functional features (Figure 1E and data not shown). MLL-GAS7 leukemias exhibited the lowest AML CFC frequencies, but morphologic appearances more akin to MLL-ENL and MLL-AF9 leukemias (Figure 1A, D), indicating that functional and morphologic features of AML cellular hierarchies are not necessarily correlated. The spectrum of disease manifestations was not due to variations in the frequency of distinct clones or the number of retroviral integrations per clone (Supplemental Figure 3). Therefore, leukemia cell hierarchy and the frequency of self-renewing Lin+ LSCs vary significantly according to the initiating MLL oncogene.

Derivation of a genetic program that maintains MLL LSCs within the self-renewing fraction of the leukemia cell hierarchy

A genetic program that distinguishes LSCs from their differentiated progeny within leukemia cell hierarchies and promotes maintenance of self-renewal was derived based on the hypothesis that it would be: (i) differentially expressed between leukemias containing LSCs at high versus lower frequencies; and (ii) concordantly regulated in LSC-enriched versus LSC-depleted cell populations within a given leukemia.

MLL leukemia molecular subtypes were therefore grouped into two classes according to their relative LSC frequencies: high LSC frequency leukemias (MLL-AF9 and MLL-ENL) and low LSC frequency leukemias (MLL-AF10, MLL-AF1p and MLL-GAS7). Comparison of global transcriptional profiles in 34 distinct BM AML samples representative of these two groups (12 and 22, respectively) revealed 2943 differentially expressed probe sets (at significance level p≤0.01 [unpaired t-test]; median false discovery rate 12.3%; Figure 2A; Supplemental Table 4).

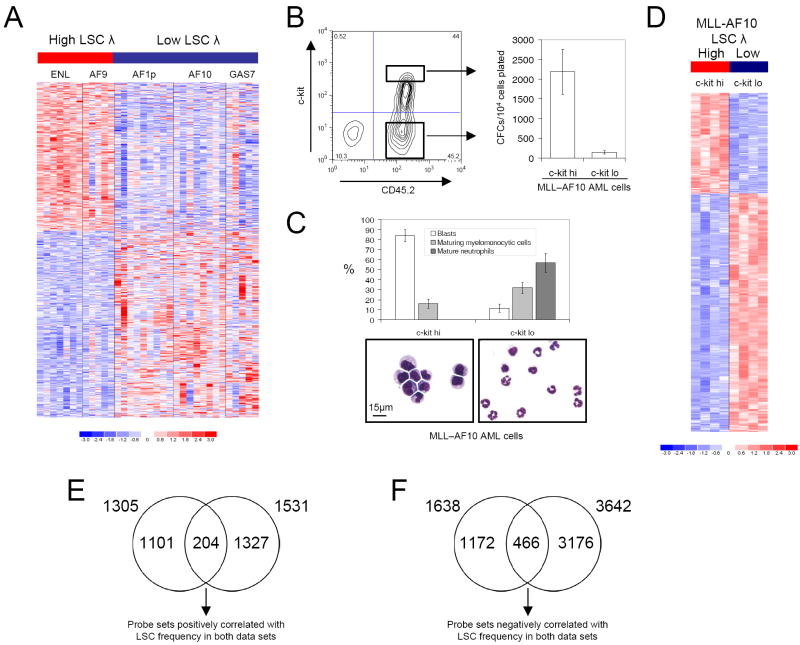

Figure 2. Derivation of an MLL LSC maintenance signature.

(A) Image represents the 2943 probe sets differentially expressed between 12 high LSC frequency AMLs (MLL-ENL and MLL-AF9) and 22 low LSC frequency AMLs (MLL-AF1p, MLL-AF10 and MLL-GAS7). Color scale indicates normalized expression values.

(B) MLL-AF10 leukemic splenocytes were FACS sorted for high or low level c-kit expression, as indicated in the representative plot. Bar graph shows clonogenic potentials of the sorted sub-populations in semi-solid culture (mean ±SEM; n=4). AML was initiated by transplantation of immortalized CD45.2+ c-kit+ BM stem and progenitor cells.

(C) Bar graph and representative images show morphology of sorted leukemia cell populations (mean ± SEM; n=4). Scale bar applies to both images.

(D) Image represents the 5173 probe sets differentially expressed between high LSC frequency (c-kithi) and low LSC frequency (c-kit-) MLL-AF10 leukemia cell sub-populations. Color scale indicates normalized expression values.

(E & F) Venn diagrams show the intersection of probe sets positively (E) and negatively (F) correlated with LSC frequency from the analyses shown in panels A and D.

Leukemia cells from mice with MLL-AF10 AML were then fractionated into separate sub-populations on the basis of c-kit expression, which correlates with MLL LSC frequency (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006). The sorted AML sub-populations exhibited substantial differences in their frequencies of AML CFCs/LSCs (mean 14-fold; Figure 2B) and morphologic features (Figure 2C), consistent with a leukemia cell hierarchy with maturation through to terminally differentiated neutrophils. Comparison of global transcriptional profiles of the LSC-enriched (c-kithi) versus LSC-depleted (c-kitlo) populations from within individual leukemias revealed 5173 differentially expressed probe sets (at significance level p≤0.01 [unpaired t-test]; Figure 2D and Supplemental Table 5).

The respective data sets from the above analyses were intersected to identify core gene sets that positively or negatively correlate with LSC potential (Figures 2E and 2F). Expression of 204 probe sets was found to be positively correlated with high LSC frequency across the different molecular subtypes of MLL leukemia, and concordantly down regulated between LSC-enriched versus depleted populations (Figure 2E and Supplemental Table 6). Conversely, the expression of 466 probe sets was negatively correlated with LSC frequency across the different molecular subtypes of MLL leukemia, and concordantly up-regulated from LSC-enriched to depleted populations (Figure 2F and Supplemental Table 7; p<0.001 for both intersections using Pearson’s Chi Square Test). The 185 genes (204 probe sets) whose expression positively correlated with LSC frequency, along with the 375 genes (466 probe sets) whose down-regulation correlated with LSC frequency, are hereafter collectively termed the LSC maintenance program.

LSCs in murine MLL myeloid leukemia are metabolically active, proliferating cells

In contrast to the assumption that AML LSCs are predominantly quiescent (Jordan et al., 2006), gene ontology (GO) annotations of up-regulated LSC maintenance program genes were consistent with LSCs being metabolically active, cycling cells (Figure 3A). Furthermore, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; Subramanian et al, 2005) revealed significant enrichments of expression of curated gene sets for cell cycle, metabolism, and Myc targets in high LSC frequency cell populations by comparison with their respective low LSC frequency populations (Supplemental Table 8). Cell cycle analyses performed on AML sub-populations sorted for different levels of c-kit expression (Figure 3B), which correlates with LSC frequency (Figure 2B, and Somervaille and Cleary, 2006), showed that fractions containing the highest frequency of LSCs also contained the highest proportion of cycling cells (Figure 3B). Thus, LSCs in this model of AML are predominantly metabolically active, cycling cells.

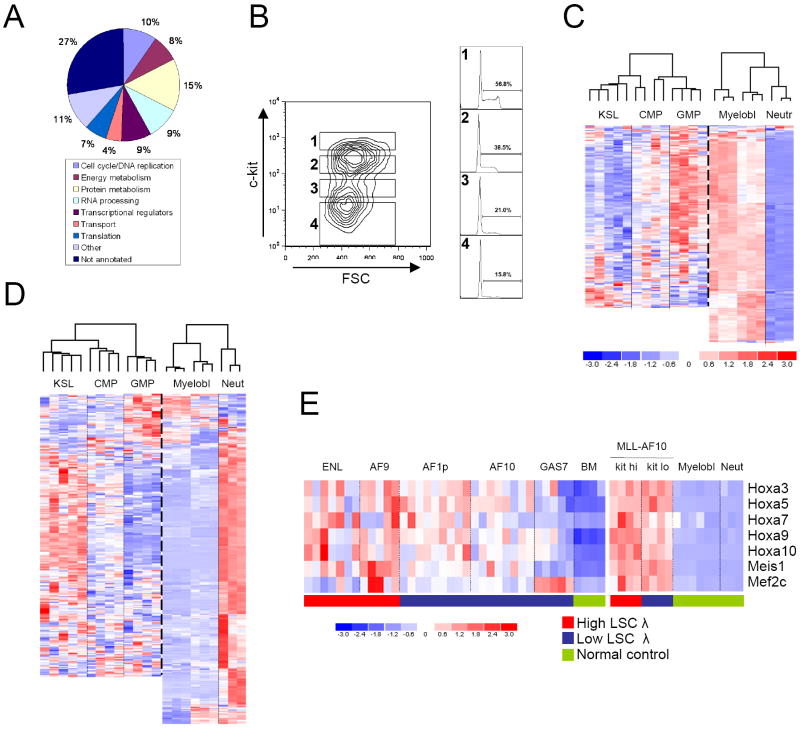

Figure 3. Biologic features of MLL LSCs.

(A) Gene ontology analysis of genes within the LSC maintenance signature based on their biologic process annotations.

(B) Mac1+ splenocytes from a mouse with MLL-AF9 AML were FACS sorted using the gates indicated in the representative plot. Sorted cells within each fraction were then analyzed for their cell cycle status (right hand plots).

(C & D) Unsupervised cluster analysis of the expression patterns of LSC maintenance signature genes positively (C) or negatively (D) correlated with LSC function, in defined populations of normal hematopoietic cells. Values from KSL, CMP and GMP cells (Krivtsov et al., 2006) and normal myeloblasts and neutrophils (this study) were utilized. Not all of the genes in the signature are represented on the Affymetrix 430A 2.0 chip used by Krivtsov et al. Color scale applies to both images and represents normalized expression values.

(E) Heat map shows expression of Hoxa, Meis1 and Mef2c genes in microarray analyses of MLL leukemias with high or low frequencies of LSCs (left panel), and in sorted sub-populations of MLL-AF10 leukemias with high (c-kithi) or low (c-kitlo) frequencies of LSCs (right panel). Expression values for whole bone marrow (left panel) and prospectively isolated normal myeloblasts or neutrophils (right panel) are shown for comparison (Normal control).

The LSC maintenance program represents a committed myeloid, as opposed to HSC, transcriptional program

Up-regulated LSC maintenance program genes displayed highest relative expression during normal hematopoiesis in mid-myeloid lineage cells (granulocyte-macrophage progenitors and myeloblasts) versus lower levels in KSL (c-kit+ Scal+ Lin-) cells and terminally differentiated neutrophils (Figure 3C and Supplemental Figure 4). Conversely, an inverse pattern of expression was observed for genes negatively correlated with LSC potential (Figure 3D). Thus, a critical effect of MLL oncogenes is to convert a normal mid-myeloid lineage program into an AML LSC maintenance program. Consistent with these observations, GSEA revealed that leukemia cell populations containing high frequencies of LSCs exhibited enriched expression of genes expressed in normal lineage-committed hematopoietic progenitors (Ivanova et al. 2002), but not genes expressed in long-term HSCs (Supplemental Table 8).

Notably, Hoxa and Meis1, which are prominently expressed in KSL cells, did not feature in the LSC maintenance signature, nor did KSL transcripts previously shown to be shared with MLL-AF9 LSCs (Krivtsov et al., 2006; Supplemental Figure 5). Although required for leukemic transformation of BM stem and progenitor cells by MLL oncogenes (Ayton and Cleary, 2003; So et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2007), Hoxa/Meis1 and Mef2c levels did not vary concordantly with LSC frequency (Figure 3E). Indeed, spontaneous terminal leukemia cell differentiation and loss of self-renewal potential in MLL-AF10 leukemias (Figure 2B, C) occurred in the presence of substantially elevated Hoxa and Meis1 expression, which did not vary significantly between LSC enriched and LSC depleted sub-populations (Figure 3E). Thus, MLL LSCs are metabolically active, aberrantly self-renewing, committed myeloid cells, rather than HSCs aberrantly expressing myeloid lineage antigens, and undergo loss of self-renewal potential in vivo in the presence of relatively high level expression of Hoxa and Meis1 transcripts.

MLL LSCs share transcriptional similarities with embryonic stem cells and poor prognosis human malignancies, including pediatric leukemia

Poor prognosis in a diverse set of human malignancies is associated with the expression of an embryonic stem cell-like (ESC) program (Wong et al., 2008; Ben-Porath et al., 2008). GSEA demonstrated that expression of ESC-like program genes was substantially enriched in the high versus low LSC frequency MLL leukemia cell populations, in contrast to the reverse enrichment of an adult stem cell core program (Wong et al., 2008) in LSC-depleted populations (Figure 4A and Table 1). Enrichment for an ESC-like program was not driven by proliferation genes since the significance of the correlation was maintained when genes with cell cycle functional annotations were excluded from the analysis (Table 1). The ESC-like state in MLL LSCs was not induced by genes such as Pou5f1, Nanog or Sox2, which were not significantly expressed (data not shown), nor co-ordinate expression of their downstream transcriptional effecters (Boyer et al., 2005), which were not enriched in MLL LSCs (Table 1).

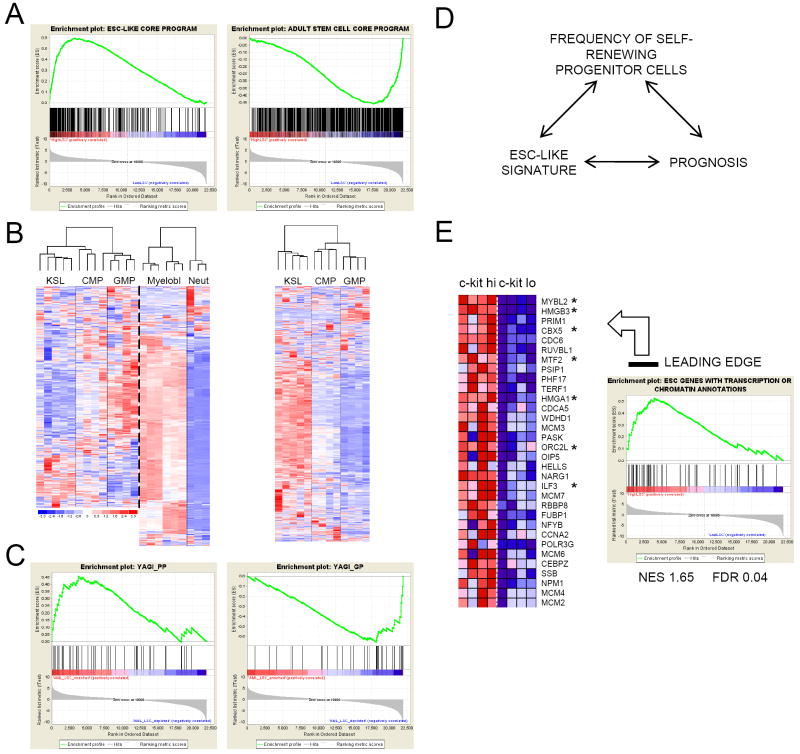

Figure 4. Shared transcriptional features of MLL LSCs, ESCs, normal myeloid progenitors and poor prognosis human malignancies, including pediatric leukemia.

(A) GSEA plots show that expression of an ESC-like core gene module (Wong et al., 2008; Supplemental Table 9) is enriched in high (c-kithi) vs low (c-kitlo) LSC frequency MLL-AF10 leukemia cell populations (left panel), whereas the reverse correlation is observed for an adult tissue stem cell module (right panel).

(B) Unsupervised cluster analysis of the expression pattern of ESC-like core module genes (left panel) and adult tissue stem cell module genes (right panel) (Wong et al., 2008) in the indicated defined populations of normal hematopoietic cells (Krivtsov et al., 2006 and this study). Color scale indicates normalized expression values.

(C) GSEA plots show expression of poor prognosis genes in pediatric myeloid leukemia (Yagi et al., 2003; Supplemental Table 9) is enriched in high (c-kithi) vs low (c-kitlo) LSC frequency MLL-AF10 leukemia cell populations (left panel), whereas the reverse correlation is observed for good prognosis genes (right panel).

(D) Suggested link between an ESC-like transcriptional signature, prognosis and cancer stem cell frequency in human malignancy.

(E) Leading edge analysis of GSEA plot shows enriched expression of ESC-like genes with transcription or chromatin annotations (Ben-Porath et al., 2008; Supplemental Table 9) in high (c-kithi) vs low (c-kitlo) LSC frequency MLL-AF10 leukemia cell populations. Those marked with an asterisk, or their close homologues, are found within the LSC maintenance signature.

Table 1.

Gene Set Enrichment Analyses

| Gene Set Name* | High vs Low LSC Frequency AML Comparison (Figure 2A) | c-kit+ vs c-kit-AML Comparison (Figure 2D) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NES | FDR | NES | FDR | |

| Stem Cell Gene Sets | ||||

| CORE ESC-LIKE GENE MODULE (Wong et al., 2008) | 1.69 | 0.02 | 1.75 | 0.03 |

| CORE ESC-LIKE GENE MODULE WITHOUT PROLIFERATION GENES | 1.76 | 0.03 | 1.83 | 0.02 |

| ADULT TISSUE STEM MODULE | -1.13 | 0.36 | -1.74 | 0.03 |

| ES expressed 1 (Assou et al., 2007; Ben-Porath et al., 2008) | 1.26 | 0.19 | 1.66 | 0.03 |

| ES expressed 2 (Ben-Porath et al., 2008) | 1.52 | 0.09 | 1.58 | 0.03 |

| NOS TFs (Boyer et al., 2008; Ben-Porath et al., 2008) | 1.0 | 0.45 | -1.38 | 0.17 |

| Human Cancer Gene Sets | ||||

| YAGI_AML_PROGNOSIS (POOR PROG SET) | 1.39 | 0.11 | 1.42 | 0.07 |

| YAGI_AML_PROGNOSIS (GOOD PROG SET) | -1.53 | 0.07 | -1.76 | 0.02 |

| BRCA_PROGNOSIS_NEG | 1.65 | 0.19 | 1.51 | 0.20 |

| VANTVEER_BREAST_OUTCOME_GOOD_VS_POOR_DN | 1.60 | 0.20 | 1.42 | 0.23 |

| CANCER_UNDIFFERENTIATED_META_UP | 1.43 | 0.26 | 1.54 | 0.19 |

| ZHAN_MULTIPLE_MYELOMA_SUBCLASSES_DIFF | 1.66 | 0.20 | 1.45 | 0.23 |

Expression of ESC-like program genes was also transiently induced during normal myeloid differentiation, whereas expression of adult stem cell core genes was suppressed upon exit from the KLS compartment (Figure 4B). This showed that the normal mid-myeloid program co-opted by MLL oncoproteins to maintain LSCs in a self-renewing state exhibits shared features with ESCs. Furthermore, expression of gene sets associated with poor prognosis in a diverse set of human cancers, including pediatric myeloid leukemia (Yagi et al., 2003), was enriched in high versus low LSC frequency cell populations (Figure 4C and Table 1). Taken together, these observations suggest a link between prognosis in human cancer and the frequency of aberrantly self-renewing progenitor cells downstream of the tissue stem cell (Figure 4D).

Genes that regulate transcription and chromatin are candidate critical drivers of the shared transcriptional and biologic properties of both self-renewing LSCs and ESCs. In a leading edge analysis of the expression of ESC-like program genes with transcription or chromatin annotations in high versus low LSC frequency populations (Figure 4E), there was prominent placement of genes found within the LSC maintenance signature (e.g. Hmgb3, Cbx5, Mtf2, Orc2l), or of genes with close homologues within the signature (e.g. Mybl2, Ilf3). Thus, regulators of transcription or chromatin, or their close homologues, that are expressed in ESCs are also expressed in MLL LSCs.

Validation of the MLL leukemia maintenance program indicates critical collaborative roles for Myb, Cbx5 and Hmgb3

To validate the role of the maintenance program in LSC self-renewal, three transcription or chromatin regulators were selected for further study: Myb, a transcription factor required for in vitro transformation of murine bone marrow progenitor cells by MLL-ENL (Hess et al., 2006); Cbx5 (HP1α), an epigenetic repressor that binds the histone H3-K9 methylation mark to promote heterochromatin formation (Bannister et al., 2001); and Hmgb3, a high mobility group box protein that regulates self-renewal in normal HSCs (Nemeth et al., 2006). Consistent with their potential roles in maintaining LSC self-renewal, the expression of all three genes was substantially reduced concomitant with loss of clonogenic activity and induction of macrophage differentiation in transformed hematopoietic progenitors following inactivation of an MLL-ENL-ER conditional oncoprotein (Ayton and Cleary, 2003) by withdrawal of 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Figure 5A).

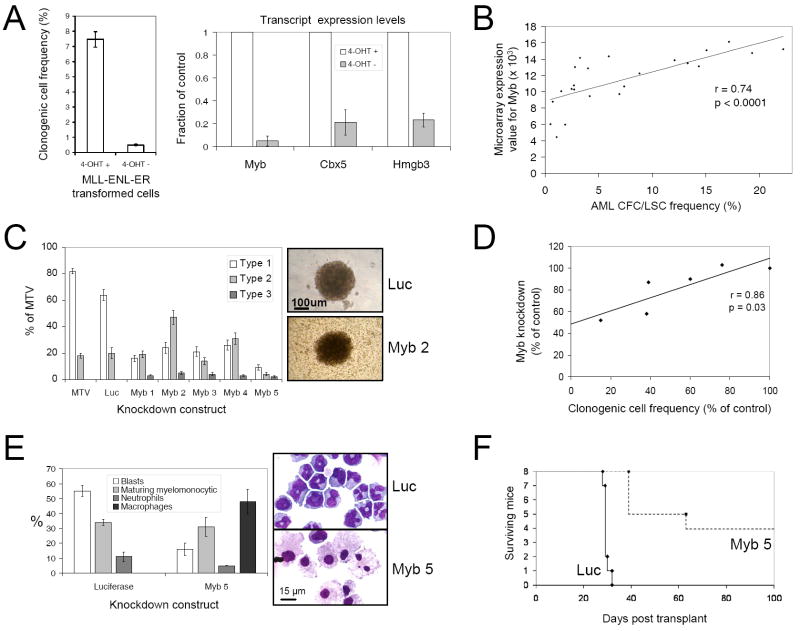

Figure 5. Myb is a critical component of the MLL LSC maintenance signature.

(A) Bar graph (left panel) shows clonogenic potentials of c-kit+ bone marrow stem and progenitor cells transformed by MLL-ENL-ER and then cultured in the presence or absence of 4-OHT for seven days (mean ±SEM; n=4). Bar graph (right panel) shows expression of Myb, Cbx5 and Hmgb3 transcripts in cells deprived of 4-OHT by comparison with control cells exposed to 4-OHT (mean ±SEM; n=4).

(B) Graph shows that Myb transcript levels (microarray expression value) correlate significantly with LSC frequencies (see Figure 1A) within individual leukemias (n=23 separate leukemias; n=3-6 for each of the five MLL molecular subtypes in this study).

(C) Bar graph shows CFC potentials of MLL-ENL AML cells transduced with lentiviruses containing shRNA constructs targeting Myb or Luciferase transcripts, by comparison with control cells transduced with an empty lentivirus (MTV), stratified by colony types (indicated in the representative images; mean ±SEM; n=4). Transduced AML cells were FACS sorted for mCherry expression 48 hours following lentiviral transduction.

(D) Graph demonstrates that the extent of Myb knockdown measured by quantitative PCR in transduced cells 48 hours following lentiviral transduction correlated significantly with the inhibition of AML CFC/LSC formation for each of the five Myb knockdown constructs.

(E) Bar graph (mean±SEM; n=4) and representative images show morphologic analysis of Myb knockdown and control MLL-ENL AML cells 48 hours following transduction.

(F) Survival curves of sub-lethally irradiated syngeneic mice transplanted with 2.5-25×104 MLL-ENL AML cells transduced with lentiviruses targeting Myb or Luciferase expression.

When assessed across 23 distinct AMLs, Myb transcript levels correlated significantly with LSC frequencies (Figure 5B). Furthermore, Myb knockdown reduced AML CFC/LSC frequencies (Figure 5C) in direct proportion to the extent of knockdown (Figure 5D) without inducing apoptosis (Supplemental Figure 6), and surviving colonies predominantly featured Type 2 or Type 3 morphology consistent with Myb reduction promoting terminal leukemia cell differentiation (Figure 5C, E). Mice secondarily transplanted with Myb knockdown AML cells displayed reduced leukemia incidence (50%) with considerably longer latencies compared to controls (Figure 5F). Knockdown of Cbx5 or Hmgb3, but not three other up-regulated LSC maintenance program genes (E2f6, Serbp1 and Pebp1; data not shown), also significantly reduced the frequency of AML CFCs/LSCs (Figures 6A and 6B) in direct proportion to the degree of knockdown (Figure 6C), also without inducing apoptosis (Supplemental Figure 6). By contrast, enforced expression of genes negatively correlated with LSC potential (Klf3, Klf13 but not Smad4; Supplemental Figure 7) abrogated AML CFC/LSC potential.

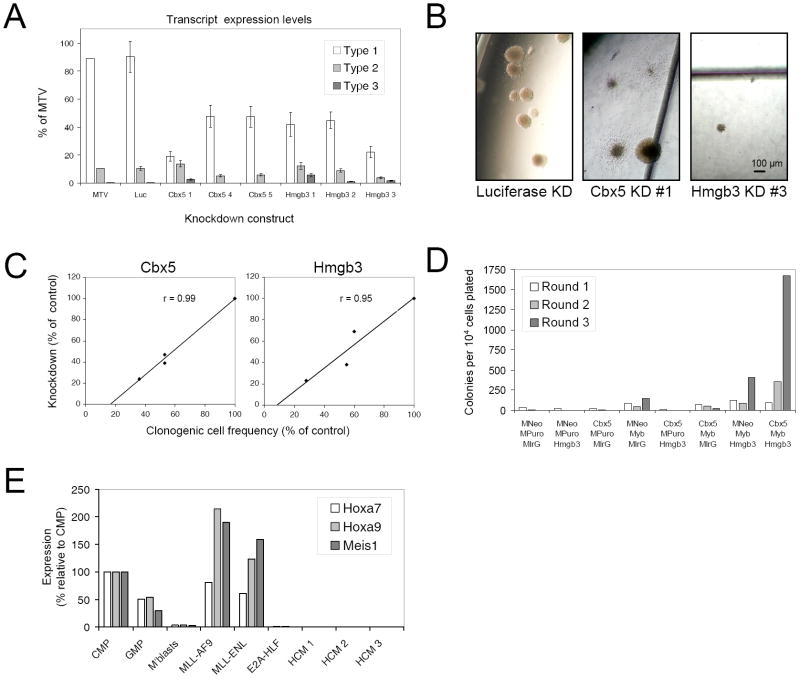

Figure 6. Requirement of Hmgb3 and Cbx5 for the cooperative maintenance of MLL LSC potentials.

(A & B) Bar graph shows clonogenic/LSC potentials (mean ±SEM) of MLL-ENL AML cells transduced with lentiviruses containing shRNA constructs targeting Cbx5, Hmgb3 or Luciferase expression, by comparison with control cells transduced with an empty lentivirus (MTV). Transduced AML cells were FACS sorted for mCherry expression 48 hours following lentiviral infection. Colony types are indicated (A) and representative images are shown (B). Scale bar applies to all images.

(C) Graphs demonstrate that the extent of Cbx5 and Hmgb3 knockdown measured by quantitative PCR in transduced cells 48 hours following lentiviral transduction correlated with the inhibition of AML-CFC/LSC potential.

(D) Bar graph shows serial replating potentials of c-kit+ bone marrow stem and progenitor cells triple co-transduced with all possible combinations of Myb, Cbx5, Hmgb3 and control viruses. MNeo – MSCV Neo; MPuro – MSCV Puro; MIrG – MSCV IRES-GFP.

(E) Bar graph shows relative expression of Hoxa7, Hoxa9 and Meis1, as determined by quantitative PCR, in prospectively sorted normal murine bone marrow progenitor subsets (CMP, GMP and c-kit+ Mac1+ myeloblasts) and in c-kit+ bone marrow stem and progenitor cells immortalized by the indicated oncogenes, or co-expression of Myb, Cbx5 and Hmgb3 (HCM – 3 separate lines are shown).

Neither Myb, Cbx5 or Hmgb3, however, induced serial replating in semi-solid culture when individually transduced into c-kit+ BM stem and progenitor cells (Figure 6D and data not shown). The clonogenic potentials of transduced cells were either weakly enhanced (Myb) or not enhanced (Cbx5 or Hmgb3) in the third round of culture by comparison with cells transduced with control retroviruses. In pairwise combinations Hmgb3 slightly enhanced the weak third round clonogenic potentials induced by expression of Myb alone, which was dramatically enhanced by further addition of Cbx5. Thus, cells co-transduced by all three genes displayed robust serial replating (Figure 6D and data not shown). Colonies were exclusively Type 1 and contained myeloblasts (c-kit+ Mac1+ Gr1+ immunophenotype) that readily adapted to growth in liquid culture (data not shown). Effective bypass of the upstream MLL transformation pathway was confirmed by lack of Hoxa and Meis1 expression in cells immortalized by the combined actions of Myb, Cbx5 and Hmgb3 (Figure 6E). Thus, individual genes of the program are necessary but not sufficient for LSC maintenance. However, they suffice for _Hoxa/Meis1_-independent immortalization when simultaneously co-expressed, thereby establishing their cooperative roles in the LSC maintenance program.

Discussion

The cancer stem cell model predicts that malignancies are organized into cellular hierarchies characterized by differing self-renewal potentials, such that a significant fraction of cells in the tumor clone is incapable of self-renewal despite shared genetic features with the CSC fraction (Clarke et al., 2006). Recent studies, however, have demonstrated that CSCs may be considerably more frequent than predicted by xenogeneic transplantation assays, and have raised questions as to the validity and generality of the cancer stem cell model as well as the existence and extent of CSC hierarchical relationships (Kelly et al., 2007). Identification of molecular pathways that regulate the self-renewing fraction of CSCs within a malignancy would illustrate the nature of potential CSC hierarchies and additionally hold out promise for the development of therapies that specifically target the critical cellular components of malignant disease. Our current studies demonstrate that MLL LSCs are actively cycling downstream myeloid precursors occupying the apex of a leukemia cell hierarchy, and maintained in a self-renewing state by a genetic program more akin to embryonic than adult stem cells. This contrasts with previous suggestions that LSCs are synonymous with HSCs or exclusively maintained by corrupted HSC-specific programs (Bonnet and Dick, 1997; Krivtsov et al., 2006). Despite the downstream character of LSCs in this model of AML, our studies provide unequivocal support for a hierarchical leukemia cell organization and, in fact, further suggest that the relative abundance of self-renewing cells in human cancers may be an important prognostic factor.

MLL oncogenes differentially specify LSC hierarchies and frequencies

MLL oncogenes are structurally heterogeneous due to differences in their respective fusion partners, which have previously been suggested to “instruct” certain biological properties of leukemia such as disease latency and lineage of the leukemic blasts (Lavau et al., 1997; Lavau et al., 2000; Cano et al., 2007; Wong et al., 2007). Consistent with this, our comparative analysis of several molecularly distinct MLL oncogenes under identical experimental conditions showed that MLL fusion partners determine the frequencies of LSCs, which vary by up to seven fold in a murine model of AML. At a cellular level, this reflects the abilities of MLL oncogenes to differentially specify the probability of self-renewal versus differentiation, which in turn may directly affect the cellular hierarchy and hematologic features of disease. At a molecular level, this likely reflects quantitative and/or qualitative differences in the transcriptional effecter functions of MLL fusion partners, which sustain divergent global transcriptional profiles that distinguish low versus high LSC frequency AMLs.

Our studies also provide support for the CSC model itself, which has recently been questioned (Kelly et al., 2007). For example, MLL-AF10 leukemic clones consisted of approximately 5% self-renewing LSCs as well as up to 35% terminally differentiated mature neutrophils, reflecting previous reports of neutrophilic differentiation within the leukemia clone in human AML (Fearon et al., 1986). Our observation that LSC frequencies in experimentally induced AML can vary substantially, even when initiated by broadly similar oncogenes, provides direct experimental confirmation of recent proposals (Adams et al., 2007; Kennedy et al., 2007), and further suggests that variation in LSC frequency may also be a feature of human leukemia. Consistent with this, clonogenic cell frequencies vary over a 1000-fold range (Buick et al., 1977) in AMLs, which also exhibit markedly different engraftment abilities in immune deficient mice (Pearce et al., 2006), a functional readout of LSC potential. Thus, AMLs are hierarchically organized but the LSC compartment is not necessarily a numerically fixed, prospectively definable cellular sub-fraction.

The biology of MLL LSCs is informed by their maintenance signature

LSCs can be partially enriched based on immunophenotypic and other markers, but current approaches do not enable their prospective isolation to levels of purity comparable with those achieved for isolation of normal murine HSCs. Thus, as an alternative approach to identify a transcriptional program that defines LSCs, and because cell-type specific transcripts from minority cell populations can readily be detected in bulk tumor samples (Perou et al., 2000), we intersected gene sets correlating with LSC frequency derived from two different experimental methodologies (Figures 2A and 2D), each associated with low false discovery rates.

The derived LSC maintenance program revealed several novel attributes of MLL LSCs. In contrast to the prevailing notion that AML LSCs are predominantly quiescent (Jordan et al., 2006), MLL LSCs are predominantly metabolically active, cycling cells as demonstrated by GO and GSEA analyses of the signature, and confirmed experimentally by cell cycle analysis of sorted leukemia cell sub-populations. Furthermore, up-regulated LSC maintenance program genes are maximally expressed at a mid-myeloid stage during normal differentiation (GMPs and myeloblasts) and mostly down regulated in mature neutrophils and the KSL compartment, which contains HSCs. Together with the observation that MLL LSC transcriptional profiles are enriched for expression of gene sets expressed in normal lineage-committed hematopoietic progenitor cells rather than long-term HSCs, these data emphasize that the LSC in MLL leukemias is an aberrantly self-renewing downstream myeloid cell, rather than a tissue stem cell aberrantly expressing myeloid lineage antigens (Passegue et al., 2003; Somervaille and Cleary, 2006).

Although Hoxa and Meis1 expression is induced by MLL oncoproteins (Krivtsov et al., 2006) and required for initiation of MLL leukemia (Ayton and Cleary, 2003; So et al., 2004; Wong et al., 2007), these genes were not part of the LSC maintenance program because their expression levels did not vary concordantly between leukemia cell populations containing different frequencies of LSCs. Indeed, MLL-AF10 LSCs underwent terminal granulocytic differentiation with concomitant loss of self-renewal potential in the presence of continued high level Hoxa and Meis1 transcript levels, although the possibility of post-translational regulation is not excluded. However, there is also no overlap of the maintenance program with a KSL/LSC shared signature (Krivtsov et al., 2006), defined by transcripts with high level co-expression in normal KSL cells and MLL-AF9 LSCs but low level expression in committed myeloid progenitors (CMP, GMP and MEP), which likely represents an MLL leukemia initiation program. Thus, the genetic programs required for leukemia initiation may be quite distinct from those that function to maintain LSCs within the self-renewing fraction and regulate their differentiation. It appears that a critical function of the MLL oncoprotein, through its subordinate effecters Hoxa and Meis1, is to transmute a normal mid-myeloid lineage transcriptional program into an LSC maintenance program that is not synonymous with an adult stem cell program.

The nexus of MLL LSCs, ESCs, myeloid progenitors, and poor prognosis human malignancies

Module map analysis indicates that stem cell expression programs are clustered into two distinct categories, ESC-like programs versus adult tissue stem cell-like programs (Wong et al., 2008), and that there is likely not a shared program for self-renewal in all types of stem cells, in contrast to previous suggestions (Ivanova et al., 2002). Expression of ESC-like core program genes is substantially enriched in self-renewing ESCs and MLL LSCs, as well as in diverse poor prognosis, poorly differentiated human malignancies, which may contain frequent cancer stem cells. However, our analyses also showed transient up regulation of ESC-like program genes during normal myeloid differentiation, with inverse regulation of adult stem cell core program genes, emphasizing that these dissimilar programs are not necessarily specific to self-renewing cells.

The ESC-like state in MLL LSCs was not mediated by Nanog, Pou5f1 or Sox2, critical regulators of ESC fate that are not significantly expressed in MLL LSCs. Nor was it directly controlled by Myc, which induces the ESC-like signature and regulates CSC frequency in experimentally induced human epithelial tumors (Wong et al., 2008), because LSC frequencies across distinct MLL leukemia subtypes did not correlate significantly with its expression (data not shown).

We propose a unifying model whereby the ESC-like program, which coordinately maintains proliferation and inhibits differentiation, is subordinate to diverse upstream regulators that critically sustain its expression. Upstream positive regulators of the program might include Nanog, Pou5f1 and Sox2 in ESCs, Myc in experimentally induced human skin cancer (Wong et al., 2008), and Hoxa/Meis in MLL LSCs. This model is supported by our finding that co-expression of Myb, Hmgb3 and Cbx5, genes that are expressed in both ESCs and MLL LSCs, is sufficient to induce Hoxa/Meis independent immortalization of myeloid progenitors. Although expression of the ESC-like program is induced during normal myeloid differentiation, the absence of sustained Hoxa/Meis expression in committed myeloid progenitors/precursors may permit its down regulation, allowing terminal differentiation. Conversely, an inability to normally extinguish the ESC-like program in hematopoietic progenitors is leukemogenic. This tentative model pathogenically links inappropriate expression of the initiating MLL/Hox/Meis sub-program, which is typically a feature of HSCs, with a downstream ESC-like program in maintaining the aberrant self-renewal of myeloid progenitors that serve as LSCs in _MLL_-associated AML, although how the two programs interlink is not clear.

The co-ordinate expression of ESC-like genes, rather than adult stem cell program genes, in poor prognosis human malignancies and MLL LSCs further suggests that the frequency of cancer stem cells may be more generally linked to prognosis than previously appreciated, and that these cells are more akin to aberrantly self-renewing downstream tissue progenitor cells than their normal tissue stem cell counterparts. Consistent with this possibility, adverse clinical outcome in human AML correlates with the ability of AML cells to engraft immune deficient mice (Pearce et al., 2006), a functional assay for LSC potential that may also measure their relative frequencies. Furthermore, human AML cells with downstream progenitor cell immunophenotypes are able to initiate leukemia in immune deficient mice (Taussig et al., 2008).

Cooperative roles of LSC maintenance genes as downstream effecters in MLL leukemogenesis

Knockdown of up-regulated LSC maintenance program genes (Myb, Hmgb3 and Cbx5) abrogated AML CFC/LSC potential in proportion to the extent of knockdown, validating their individual contributions. Furthermore, their simultaneous co-expression robustly induced BM stem and progenitor cell immortalization independent of Hoxa/Meis1, whereas expression of the genes individually did not. These results illustrate the cooperative and essential nature of an ESC-like LSC maintenance program, which lies downstream of the initiating MLL oncogene and its Hoxa/Meis1 effecters.

Although Hmgb3 regulates self-renewal in HSCs (Nemeth et al., 2006), and is frequently highly expressed in poor prognosis breast cancer (Ben-Porath et al., 2008), the mechanisms by which it collaborates with Myb, a key regulator of normal and leukemic haematopoiesis (Ramsay and Gonda, 2008), and Cbx5, which normally functions to promote formation of heterochromatin, to mediate LSC maintenance are currently unclear. Furthermore, it is also unclear whether down regulation of LSC maintenance program genes in vivo, which permits LSC differentiation and loss of self-renewal, is stochastic or deterministic. Nevertheless, our findings emphasize the potential for therapeutic approaches that target genes and pathways that are of greater importance to the function of LSCs than HSCs, since LSCs in this model are distinguished by biological differences from normal HSCs, which are necessary for regeneration of hematopoiesis following chemotherapy.

Experimental procedures

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from either Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME), or the Stanford University Research Animal Facility, and maintained on an inbred background. For experiments requiring use of congenic marker analysis, B6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ mice, purchased from Jackson Laboratories, were used as transplant recipients. All experiments on mice in this study were performed with the approval of and in accordance with Stanford University’s Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Plasmids

Retroviral vectors containing MLL-ENL (Lavau et al., 1997), MLL-AF10 (DiMartino et al., 2002), MLL-GAS7 (So et al., 2003 (1)), MLL-AF1p (So et al., 2003 (2)), MLL-ENL-ER (Ayton and Cleary, 2003) (all in pMSCV Neo) or MLL-AF9 (pMSCV Puro; Somervaille and Cleary, 2006), and preparation of retroviral supernatants, have been previously described. Other retroviral vectors used included: HA-Cbx5 (NM_007626) in pMSCVNeo, Myc-tagged Myb (NM_010848) in pMSCVPuro, HA-Hmgb3 (NM_008253), HA-Klf3 (NM_008453), HA-Klf13 (NM_021366) and HA-Smad4 (NM_008540) (all in pMSCV-ires-GFP). The pSicoR lentiviral vector (Ventura et al., 2004) was adapted to express the monomeric red fluorescent protein mCherry (Shaner et al., 2004). shRNAs were designed using pSicoOligomaker v1.5 (http://web.mit.edu/ccr/labs/jacks/protocols/pSico.html) and sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 10. Lentiviral supernatants were manufactured as described (Wong et al., 2007).

Bone marrow stem/progenitor cell transduction, transplantation, and colony-forming assays

C-kit+ BM stem and progenitor cells were isolated from donor mice and transduced with retroviruses as previously described (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006). For triple transductions, BM cells were spinoculated sequentially with each retroviral supernatant for 30 minutes at 32°C and 1350g. Transduced cells (3-10×105) were transplanted by retro-orbital injection immediately following spinoculation into lethally irradiated (900 cGy) syngeneic recipient mice, together with an additional radioprotective dose of 2×105 nucleated whole BM cells. An aliquot of the post-spinoculation cells was cultured in methylcellulose medium with 20 ng/ml SCF, 10 ng/ml IL-6, 10 ng/ml GM-CSF and 10 ng/ml IL-3 (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ), in the presence or absence of G418 or puromycin drug selection, to determine retrospectively the transplanted dose of transduced CFCs.

For congenic transplantation analyses, post-spinoculation CD45.2+ cells were serially replated in semi-solid culture for three rounds, as previously described (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006). 8×105 pooled, washed cells were then transplanted into sub-lethally irradiated CD45.1+ recipients (450 cGy).

For mouse leukemia CFC assays and limit dilution secondary transplantation assays, splenocytes frozen in 10% DMSO were thawed and then rested in RPMI with 20% fetal calf serum and 20% WEHI-conditioned medium for four hours. FACS sorted Mac1+ PI- cells were then plated in semi-solid culture, as above, for six days prior to colony enumeration, or injected in varying doses into sub-lethally irradiated syngeneic recipients. For secondary transplantation of cells derived from a single AML CFC, individual AML colonies were plucked from semi-solid culture after five days, replated once and then, after a further five days, 2.5×105 cells were washed and injected into sub-lethally irradiated syngeneic recipients. For secondary transplantation of AML cells transduced with Myb knockdown or control lentiviruses, cells were sorted by FACS 48 hours following transduction for red fluorescence and then transplanted into sub-lethally irradiated syngeneic mice.

Flow cytometry

Analyses were performed, as previously described (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006), using an LSR Model 1a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Some analyses and all cell sorting experiments were performed using a dual laser FACS Vantage (BD Biosciences). The following antibodies were used (from eBioscience, San Diego, CA or BD Biosciences where indicated): Mac1-FITC (eB) or Cy7APC (BD) (clone M1/70), Gr1-PE or Cy7PE (clone RB6-8C5, eB), c-kit-APC (clone 2B8, eB), F4/80-PE (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), CD45.2-FITC (clone 104; BD) and CD45.1-PE (clone A20; BD).

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction assays

Quantitative PCR was performed as described (Somervaille and Cleary, 2006) using the following primer sets from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA): Myb (Mm00501741_m1), Cbx5 (Mm00483092_m1), Hmgb3 (Mm01281712_g1), Hoxa7 (Mm00657963_m1), Hoxa9 (Mm00439364_m1), Meis1 (Mm00487664_m1) and Actb (Mm00607939_s1).

Microarray and bioinformatics analyses

For whole MLL leukemias, RNA was extracted from at least 5×106 BM leukemia cells using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For sorted MLL-AF10 leukemia cell and normal myeloid cell sub-populations, RNA was prepared using an RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was confirmed using an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For whole MLL leukemias, cDNA and cRNA were synthesized, fragmented and hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For sorted MLL-AF10 leukemia cell and normal myeloid cell sub-populations RNA was amplified using a GeneChip Two-Cycle Target Labeling and Control Reagents kit (Affymetrix) and cRNA was hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Genome 430 2.0 microarrays (Affymetrix), as per manufacturer’s instructions. Hybridized chips were scanned using the GeneChip Scanner 3000, with GeneChip operating software (v1.1.1) (Affymetrix). Raw data are available for download from Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE13690; GSE13692; GSE13693).

Whole MLL leukemia BM data sets were normalized using Microarray Analysis Software v5.0 (Affymetrix). All other normalizations (including downloaded CEL file data from Krivtsov et al. (2006)), together with all data set comparisons and cluster analyses, were performed using dChip 2007 (DNA-Chip Analyzer) software (Li and Wong, 2001; biosun1.harvard.edu/complab/dchip/manual.htm). A perfect-match/mismatch (PM/MM) model was used for the calculation of expression values. Differentially regulated probe sets in whole MLL leukemias, and in sorted leukemia cell sub-populations, were determined using p≤0.01 (unpaired t-test) as the sole comparison criterion. Median false discovery rate (FDR) was assessed using 1000 data permutations. Probe set lists were intersected using a web-based tool (jura.wi.mit.edu/bioc/tools/compare.html). For certain analyses, expression values for defined gene sets were extracted from normalized data sets using the Excel function VLOOKUP. Unsupervised cluster analysis, with masking of redundant probe sets to exclude gene duplicates, was performed using the resultant tab-delimited text files. HUGO gene names of core ESC-like gene module genes and adult stem cell tissue module genes were converted into 430 2.0 Affymetrix probe set identifiers using a webtool (www.affymetrix.com).

Gene ontology analysis was performed using MGI Gene Ontology Term Finder (proto.informatics.jax.org/prototypes/GOTools/web-docs/MGI_Term_Finder.html).

Gene set enrichment analyses (Subramanian et al., 2005) were performed using GSEA v2.0 software (www.broad.mit.edu/gsea), with a tTest metric for gene ranking and 1000 data permutations.

Supplementary Material

01

02

03

04

05

06

07

Acknowledgments

We thank Maria Ambus, Cita Nicholas, Jude Aldaco and Letha Phillips for technical support; Scott Kogan for consultation on leukemia classifications; Bill Wong for MLL-ENL-ER cells; Robert Tibshirani, Francesca Ficara and Crispin Miller for helpful discussions; and Julien Sage and Patrick Viatour for the mCherry construct. T. C. P. S. was supported by a Leukaemia Research Fund (UK) Senior Clinical Fellowship and by Cancer Research UK grant number C147/A6058. C. J. M. was supported by PHS grant T32 CA09151 awarded by the National Cancer Institute, DHHS. J.L.R. is a Fellow and H.Y.C. is the Kenneth G. and Elaine A. Langone Scholar of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation. We acknowledge support from the American Cancer Society (H.Y.C.), Children’s Health Initiative of the Packard Foundation, PHS grants CA55029 and CA116606, and the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams JM, Kelly PN, Dakic A, Nutt SL, Strasser A. Response to Comment on “Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells”. Science. 2007;318:1722. doi: 10.1126/science.1142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assou S, Le Carrour T, Tondeur S, Strom S, Gabelle A, Marty S, Nadal L, Pantesco V, Reme T, Hugnot JP, et al. A meta-analysis of human embryonic stem cells transcriptome integrated into a web-based expression atlas. Stem Cells. 2007;25:961–973. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton PM, Cleary ML. Transformation of myeloid progenitors by MLL oncoproteins is dependent on Hoxa7 and Hoxa9. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2298–2307. doi: 10.1101/gad.1111603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I, Thomson MW, Carey VJ, Ge R, Bell GW, Regev A, Weinberg RA. An embryonic stem cell-like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nat Genet. 2008;40:499–507. doi: 10.1038/ng.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Guenther MG, Kumar RM, Murray HL, Jenner RG, et al. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122:947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buick RN, Till JE, McCulloch EA. Colony assay for proliferative blast cells circulating in myeloblastic leukaemia. Lancet. 1977;1:862–863. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92818-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano F, Drynan LF, Pannell R, Rabbitts TH. Leukaemia lineage specification caused by cell-specific Mll-Enl translocations. Oncogene. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke MF, Dick JE, Dirks PB, Eaves CJ, Jamieson CH, Jones DL, Visvader J, Weissman IL, Wahl GM. Cancer stem cells--perspectives on current status and future directions: AACR Workshop on cancer stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9339–9344. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMartino JF, Ayton PM, Chen EH, Naftzger CC, Young BD, Cleary ML. The AF10 leucine zipper is required for leukemic transformation of myeloid progenitors by MLL-AF10. Blood. 2002;99:3780–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.10.3780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearon ER, Burke PJ, Schiffer CA, Zehnbauer BA, Vogelstein B. Differentiation of leukemia cells to polymorphonuclear leukocytes in patients with acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:15–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198607033150103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess JL, Bittner CB, Zeisig DT, Bach C, Fuchs U, Borkhardt A, Frampton J, Slany RK. c-Myb is an essential downstream target for homeobox-mediated transformation of hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2006;108:297–304. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova NB, Dimos JT, Schaniel C, Hackney JA, Moore KA, Lemischka IR. A stem cell molecular signature. Science. 2002;298:601–604. doi: 10.1126/science.1073823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan CT, Guzman ML, Noble M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1253–1261. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra061808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PN, Dakic A, Adams JM, Nutt SL, Strasser A. Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells. Science. 2007;317:337. doi: 10.1126/science.1142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy JA, Barabe F, Poeppl AG, Wang JC, Dick JE. Comment on “Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells”. Science. 2007;318:1722. doi: 10.1126/science.1149590. author reply 1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SC, Ward JM, Anver MR, Berman JJ, Brayton C, Cardiff RD, Carter JS, de Coronado S, Downing JR, Fredrickson TN, et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of nonlymphoid hematopoietic neoplasms in mice. Blood. 2002;100:238–245. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.1.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krivtsov AV, Twomey D, Feng Z, Stubbs MC, Wang Y, Faber J, Levine JE, Wang J, Hahn WC, Gilliland DG, et al. Transformation from committed progenitor to leukaemia stem cell initiated by MLL-AF9. Nature. 2006;442:818–822. doi: 10.1038/nature04980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavau C, Luo RT, Du C, Thirman MJ. Retrovirus-mediated gene transfer of MLL-ELL transforms primary myeloid progenitors and causes acute myeloid leukemias in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10984–10989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190167297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavau C, Szilvassy SJ, Slany R, Cleary ML. Immortalization and leukemic transformation of a myelomonocytic precursor by retrovirally transduced HRX-ENL. Embo J. 1997;16:4226–4237. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.14.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J, Sauvageau G. Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells. Nature. 2003;423:255–260. doi: 10.1038/nature01572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Wong WH. Model-based analysis of oligonucleotide arrays: Expression index computation and outlier detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2001;98:31–36. doi: 10.1073/pnas.011404098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Look AT. Oncogenic transcription factors in the human acute leukemias. Science. 1997;278:1059–1064. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5340.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth MJ, Kirby MR, Bodine DM. Hmgb3 regulates the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13783–13788. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604006103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passegue E, Jamieson CH, Ailles LE, Weissman IL. Normal and leukemic hematopoiesis: are leukemias a stem cell disorder or a reacquisition of stem cell characteristics? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(Suppl 1):11842–11849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2034201100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce DJ, Taussig D, Zibara K, Smith LL, Ridler CM, Preudhomme C, Young BD, Rohatiner AZ, Lister TA, Bonnet D. AML engraftment in the NOD/SCID assay reflects the outcome of AML: implications for our understanding of the heterogeneity of AML. Blood. 2006;107:1166–1173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, Pollack JR, Ross DT, Johnsen H, Akslen LA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay RG, Gonda TJ. MYB function in normal and cancer cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:523–534. doi: 10.1038/nrc2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CW, Karsunky H, Passegue E, Cozzio A, Weissman IL, Cleary ML. MLL-GAS7 transforms multipotent hematopoietic progenitors and induces mixed lineage leukemias in mice. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:161–171. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CW, Lin M, Ayton PM, Chen EH, Cleary ML. Dimerization contributes to oncogenic activation of MLL chimeras in acute leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- So CW, Karsunky H, Wong P, Weissman IL, Cleary ML. Leukemic transformation of hematopoietic progenitors by MLL-GAS7 in the absence of Hoxa7 or Hoxa9. Blood. 2004;103:3192–3199. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somervaille TC, Cleary ML. Identification and characterization of leukemia stem cells in murine MLL-AF9 acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steidl U, Rosenbauer F, Verhaak RG, Gu X, Ebralidze A, Otu HH, Klippel S, Steidl C, Bruns I, Costa DB, et al. Essential role of Jun family transcription factors in PU.1 knockdown-induced leukemic stem cells. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1269–1277. doi: 10.1038/ng1898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taussig DC, Miraki-Moud F, Anjos-Afonso F, Pearce DJ, Allen K, Ridler C, Lillington D, Oakervee H, Cavenagh J, Agrawal SG, et al. Anti-CD38 antibody-mediated clearance of human repopulating cells masks the heterogeneity of leukemia-initiating cells. Blood. 2008;112:568–575. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-118331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura A, Meissner A, Dillon CP, McManus M, Sharp PA, Van Parijs L, Jaenisch R, Jacks T. Cre-lox-regulated conditional RNA interference from transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10380–10385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403954101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DJ, Liu H, Ridky TW, Cassarino D, Segal E, Chang HY. Module map of stem cell genes guides creation of epithelial cancer stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:333–344. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P, Iwasaki M, Somervaille TC, So CW, Cleary ML. Meis1 is an essential and rate-limiting regulator of MLL leukemia stem cell potential. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2762–2774. doi: 10.1101/gad.1602107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T, Morimoto A, Eguchi M, Hibi S, Sako M, Ishii E, Mizutani S, Imashuku S, Ohki M, Ichikawa H. Identification of a gene expression signature associated with pediatric AML prognosis. Blood. 2003;102:1849–1856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

01

02

03

04

05

06

07