Nitric oxide activates ATP-sensitive potassium channels in mammalian sensory neurons: action by direct S-nitrosylation (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels in neurons regulate excitability, neurotransmitter release and mediate protection from cell-death. Furthermore, activation of KATP channels is suppressed in DRG neurons after painful-like nerve injury. NO-dependent mechanisms modulate both KATP channels and participate in the pathophysiology and pharmacology of neuropathic pain. Therefore, we investigated NO modulation of KATP channels in control and axotomized DRG neurons.

Results

Cell-attached and cell-free recordings of KATP currents in large DRG neurons from control rats (sham surgery, SS) revealed activation of KATP channels by NO exogenously released by the NO donor SNAP, through decreased sensitivity to [ATP]i.

This NO-induced KATP channel activation was not altered in ganglia from animals that demonstrated sustained hyperalgesia-type response to nociceptive stimulation following spinal nerve ligation. However, baseline opening of KATP channels and their activation induced by metabolic inhibition was suppressed by axotomy. Failure to block the NO-mediated amplification of KATP currents with specific inhibitors of sGC and PKG indicated that the classical sGC/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway was not involved in the activation by SNAP. NO-induced activation of KATP channels remained intact in cell-free patches, was reversed by DTT, a thiol-reducing agent, and prevented by NEM, a thiol-alkylating agent. Other findings indicated that the mechanisms by which NO activates KATP channels involve direct S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues in the SUR1 subunit. Specifically, current through recombinant wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels expressed in COS7 cells was activated by NO, but channels formed only from truncated isoform Kir6.2 subunits without SUR1 subunits were insensitive to NO. Further, mutagenesis of SUR1 indicated that NO-induced KATP channel activation involves interaction of NO with residues in the NBD1 of the SUR1 subunit.

Conclusion

NO activates KATP channels in large DRG neurons via direct S-nitrosylation of cysteine residues in the SUR1 subunit. The capacity of NO to activate KATP channels via this mechanism remains intact even after spinal nerve ligation, thus providing opportunities for selective pharmacological enhancement of KATP current even after decrease of this current by painful-like nerve injury.

Background

Nitric oxide (NO) is a pivotal signaling molecule involved in many diverse developmental and physiological processes in the mammalian nervous system [1,2]. The influences of NO upon nociceptive transmission are opposing and complex [3-8], and the exact sites and mechanisms of these actions remain controversial. For example, within the spinal cord, high concentrations of NO exaggerate pain sensitivity [6], and pharmacological inhibition or genetic deletion of nNOS diminish pain behavior in several animal pain models [3,4,6,8,9]. Furthermore, expression of nNOS in sensory neurons is up-regulated following peripheral nerve injury [3,5,10], suggesting a contribution of NO to neuropathic pain. There is also evidence that NO has analgesic effects. Specifically, NO donors produce peripheral antinociceptive effects in inflammatory pain [11]. Also, low concentrations of NO acting at spinal sites attenuate allodynia following nerve injury [7,11,12]. These divergent findings reflect the site-specific complexity of NO-dependent signaling in the regulation of pain generating processes. Additionally, the NO-signaling pathway contributes to the anti-nociceptive effect of drug action at peripheral transduction sites, including that of opioids, NSAIDs, and the NO-releasing derivative of gabapentin NCX 8001 [13-16]. Some drugs produce peripheral analgesia via NO-dependent activation of ATP-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels [15,17-19].

KATP channels, widely represented in metabolically active tissues, are hetero-octamers composed of four regulatory SUR subunits (SUR1, SUR2A, or SUR2B) and four ATP-sensitive pore-forming inwardly rectifying potassium channel (Kir6.x) subunits (Kir6.1 or Kir6.2) [20]. Because their opening is determined by the cytosolic ADP/ATP ratio, KATP channels act as metabolic sensors, linking cytosolic energetics with cellular functions in various tissues [21,22]. In the central and peripheral nervous system, widely distributed KATP channels [20,23-25] regulate neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter release, ligand effects, and cell survival during metabolic stress [21,22,24,26,27].

NO regulates KATP channels that control various physiological functions, including NO-associated protection from cell death, vasodilatation, and modulation of transmitter secretion [21,22,24,26]. Therefore, we hypothesized that NO activates KATP currents in peripheral sensory neurons.

Altered sensory function contributes to the pathogenesis of neuropathic pain via hyperexcitability in injured axons [28-30] and the corresponding somata in the DRG [29,31], increased synaptic transmission at the dorsal horns [32], and loss of DRG neurons [33,34]. We have recently identified loss of KATP currents in large DRG somata from rats that demonstrated sustained hyperalgesia-type response to nociceptive stimulation after axotomy [25,35]. Thus, reduced KATP currents may be a factor in generating neuropathic pain through increased excitability, amplified excitatory neurotransmission, and enhanced susceptibility to neuronal cell death. Therefore, we also hypothesized that altered NO regulation may account for the decreased KATP channel opening following axotomy that mediates the injury effect.

Since somata of injured DRG neurons are a site of pertinent phenotypic changes, reduced KATP currents may contribute to neuropathic pain by increasing excitability, excitatory neurotransmission, and susceptibility to neuronal cell death. The established regulation of excitability by KATP currents raises the hypothesis that decreased NO regulation may account for the decreased KATP channel opening following axotomy that leads to neuropathic pain. Ionic channel modulation by NO can be produced either indirectly through the classical pathway of sGC activation and generation of cGMP, or directly through a pathway involving S-nitrosylation of target proteins [1]. S-nitrosylation regulates Na+ channels and acid-sensing ion channels in DRG neurons [36,37], but effects on DRG neuronal KATP channels have not been examined. It is also controversial whether the classical NO/sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway functions in DRG neurons. Specifically, pharmacological studies in vivo imply that KATP channels in peripheral sensory neurons may be activated indirectly via the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway [38-40]. Also, the PDE inhibitor sildenafil increases cytosolic cGMP producing peripheral analgesia via activation of the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway [41]. Molecular constituents of this classical indirect pathway have been identified in mammalian DRG neurons, including NOS [3,5,10], sGC [42,43], cGMP [44] and PKG [45]. However, other published reports failed to find cGMP activity in DRG neurons, even after the up-regulation of NOS following axotomy or perfusion with NO donors [46]. Also a recent study failed to demonstrate sGC in mouse DRG neurons [45]. Because of these various controversies, we designed additional experiments to identify the pathway by which NO regulates KATP channels in DRG neurons, using specific pharmacological tools at different levels of the cascades.

Results

In recordings of native KATP channels, we used 91 male rats: 48 controls (SS) that showed 0% probability of hyperalgesia response, and 43 rats with 46.1 ± 18% probability of hyperalgesia response (p < 0.001 vs. SS) in the ipsilateral paw after SNL (SNL). From these rats, we studied 218 control (SS) neurons with diameter 43.5 ± 4.1 μm, that did not differ from the diameter of 196 axotomized (SNL) neurons (44.7 ± 6.5 μm; p = 1.0 vs. SS).

Single channel characteristics of KATP channels in large DRG neurons dissociated from SS and SNL rats

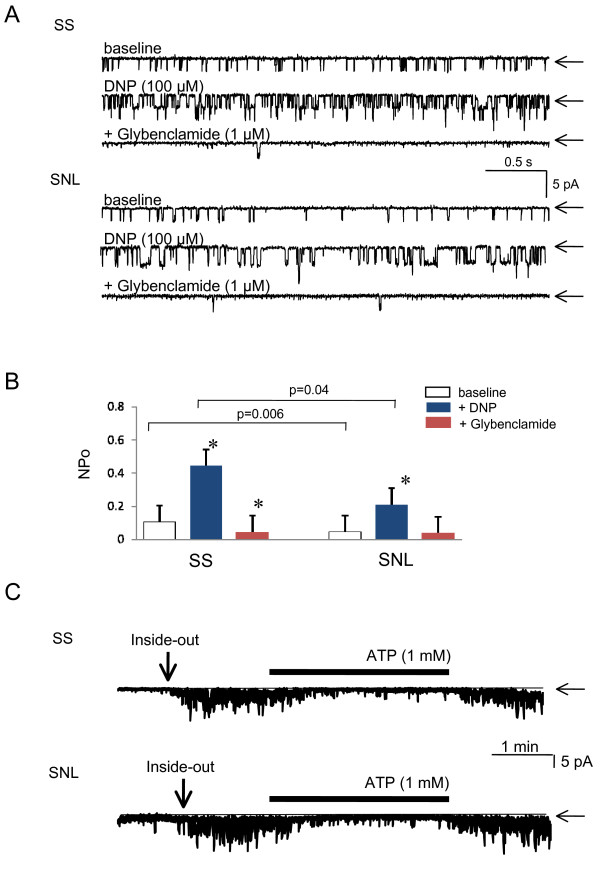

Single channel currents from either SS or SNL neurons were measured at -60 mV membrane holding potential, using cell-attached and inside-out patch clamp configurations. In cell-attached recordings, infrequent but significant spontaneous channel activity was observed in both control (SS) and SNL neurons (Figure 1A, baseline). However, this baseline activity was decreased in SNL neurons (NPo = 0.06 ± 0.02) compared with SS neurons (NPo = 0.12 ± 0.03; p = 0.006 vs. SNL; n = 8 in each group). Bath application of the uncoupler of mitochondrial ATP synthesis DNP (100 μM) gradually activated these baseline currents in both groups. However, DNP-induced channel opening was significantly reduced in SNL (NPo = 0.208 ± 0.16) compared to SS (NPo = 0.442 ± 0.26; p = 0.04 vs. SS; n = 8 in each group; Figure 1B). Addition of glybenclamide 1 μM, a specific KATP channel inhibitor, almost completely blocked DNP-induced currents in both groups, indicating that these currents are conveyed via KATP channels (p < 0.001 for each group). In inside-out patches, DNP (100 μM) had no direct effect on KATP channels (p = 1.0 vs. baseline, n = 5 in each group).

Figure 1.

Single-channel characteristics of KATP channel in DRG neurons dissociated from SS and SNL rat. (A) Representative current traces of KATP channels in SS or SNL neurons recorded in cell-attached configuration at a holding potential of -60 mV. In SS and SNL neurons, bath application of DNP (100 μM) activated KATP channel, and this channel activity was inhibited by glybenclamide (1 μM). The changes of NPo values are summarized in (B). Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 8 each). (C) Representative KATP current traces in SS or SNL neurons recorded in inside-out configuration at a holding potential of -60 mV. ATP (1 mM) was added to the intracellular solution as indicated by the horizontal solid bar. Arrows indicate closed channel state.

In order to investigate the relative contribution of the intracellular milieu to regulation of channel properties, we next examined the KATPchannel behavior in excised inside-out membrane patches. When inside-out patch recordings at a holding potential of -60 mV were obtained in ATP-free solution, intense channel activity was observed in both groups. This channel activity was reversibly blocked by 1 mM of ATP (Figure 1C). The ATP sensitivity, tested by various intracellular ATP concentrations, was not significantly different between SS (IC50 = 14.7 μM; n = 5) and SNL (IC50 = 18.1 μM; n = 5; p = 1.0 vs. SS). In addition, single channel conductance in the presence of 100 μM ATP was not significantly different between SS (69.8 ± 12 pS; n = 5) and SNL (73.2 ± 7.1 pS; n = 5; p = 1.0 vs. SS). These results suggest that axotomy by SNL does not affect directly the properties of the KATP channels.

NO donor SNAP activates KATP channels in large DRG neurons dissociated from control or SNL rats

We tested the effects of NO donor SNAP on KATP channel activity during cell-attached recordings from large DRG neurons dissociated from SS or SNL rats (Figure 2A). Bath application of SNAP (100 μM) significantly activated potassium currents in both SS and SNL neurons to a similar degree at steady state. Despite baseline difference, NPo steady-state values 10 minutes after application of SNAP were 0.27 ± 0.07 in SS and 0.31 ± 0.09 in SNL (p = 0.364; n = 7 in each group; Figure 2B). Oxidized SNAP (100 μM), which no longer releases NO [47], produced no significant activation of any potassium current either in SS (NPo = 102.3 ± 9.2% from baseline) or in SNL group (NPo = 97.0 ± 7.9% from baseline; n = 4 in each group). This discrepancy between regular and oxidized SNAP indicates that SNAP-induced current activation is dependent on release of NO from SNAP. SNAP-induced channel activity was blocked by subsequent addition of 1 μM glybenclamide in both neuronal groups, identifying the underlying conductance as KATP current. The unitary channel amplitude was not different in any experimental condition in either neuronal group, indicative of unaltered channel conductance (Figure 2A). Effects of SNAP were reversible after washout periods of 2–5 min (data not shown). In addition to SNAP, another NO donor, SNP (10 μM), produced similar activation of KATP channels in both SS and SNL neuronal populations. Specifically, NPo values 10 minutes after application of SNP were 0.24 ± 0.03 in SS (n = 3) and 0.26 ± 0.12 in SNL (n = 3) (p = 1.0).

Figure 2.

Effects of SNAP on KATP channel activity and intracellular ATP concentrations in DRG neurons. (A) Representative current traces in SS or SNL neurons recorded in cell-attached configuration at a holding potential of -60 mV. In SS and SNL neurons, bath application of NO donor, SNAP (100 μM), activated KATP channels. This channel activity was inhibited by glybenclamide (1 μM), a specific KATP channel blocker. Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) Time-dependent changes of SNAP-induced channel activity (NPo) in cell-attached recording, indicating the elapsed time to peak effect. Each point represents measurements from 8 patches (mean ± SD). (C) The concentration-dependent KATP channel activation (NPo enhancement) induced by increasing SNAP concentrations in SS (open circle) and SNL (closed circle) neurons. Each point represents measurements from 8–9 patches (mean ± SD). (D) Intracellular ATP concentration measured by a luciferin-luciferase assay. Cells were stimulated for 10 min in the presence or absence of SNAP. Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 5–6).

SNAP gradually activated KATP channels in both groups, in comparable time courses (Figure 2B). In the absence of SNAP, KATP channel activity was stable over time in cell-attached configuration (data not shown). In both neuronal groups, SNAP activation of KATP channels was concentration dependent, reaching a saturating plateau at a concentration of 100 μM or greater (Figure 2C).

Axotomy increases the excitability of DRG neurons, which consequently may change metabolic status of neurons. In addition, NO decreases intracellular ATP levels by inhibition of mitochondrial respiration in several cell types [48,49]. Therefore, we investigated whether axotomy or SNAP might alter the intracellular ATP concentrations in DRG neurons. Specifically, baseline intracellular ATP concentration did not differ between SS neurons (0.50 ± 0.10 nmol/g protein; n = 6) and SNL neurons (0.48 ± 0.13 nmol/g protein; n = 6; p = 1.00 vs. SS) (Figure 2D). SNAP also had no effect on intracellular ATP concentration 10 minutes after stimulation in DRG neurons of either SS rats (0.48 ± 0.14 nmol/g protein; n = 5; p = 1.00) or SNL rats (0.47 ± 0.19 nmol/g protein; n = 6; p = 1.00) (Figure 2D). These data suggest that SNAP-induced KATP channel activation occurs independently of changes in intracellular ATP concentration induced by either axotomy or SNAP itself in DRG neurons.

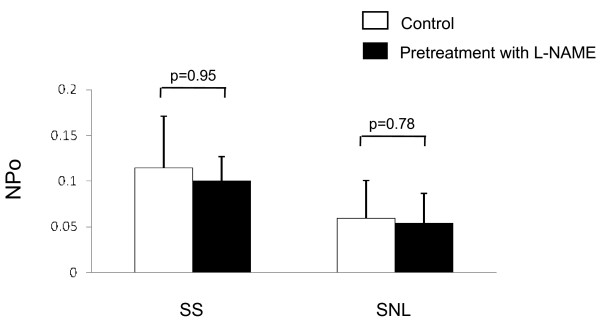

Endogenous NO does not affect baseline activity of KATP channels

In normal adult mammals, nNOS is expressed in a few small- and medium-diameter rat lumbar DRG neurons [50]. However, nNOS expression is substantially increased after peripheral nerve axotomy [51]. Although the distribution and role of nNOS in large DRG neurons remain unclear, endogenous NO produced via nNOS may affect baseline activity of KATP channel in this cell population. Therefore, we investigated the effect of endogenous NO on channel activity using L-NAME, an endogenous NOS inhibitor. Pretreatment with L-NAME (100 μM) for 20 minutes had no significant effect on baseline activity of KATP channels compared to control (vehicle only, without L-NAME) in either SS (NPo after pretreatment with L-NAME = 0.114 ± 0.06 vs. 0.105 ± 0.02 after vehicle; p = 0.95; n = 7 in each group) or SNL neurons (NPo after L-NAME = 0.06 ± 0.04 vs. 0.04 ± 0.03 after vehicle; p = 0.78; n = 7) (Figure 3). In inside-out patches, L-NAME had no direct effect on KATP channels (n = 4, p = 0.975 vs. baseline). These results indicate that endogenous NO, possibly produced by nNOS in DRG neurons, does not affect basal KATP channel activity in either SS or SNL neurons.

Figure 3.

Effects of endogenous NO on baseline KATP channel activity in DRG neurons. Baseline KATP channel activity (NPo) was recorded 20 min after pretreatment with or without L-NAME (100 μM), a non-selective endogenous NO synthetase inhibitor. Each vertical barrepresents measurements from 6–7 cell-attached patches at a holding potential of -60 mV (mean ± SD). NS = no significant.

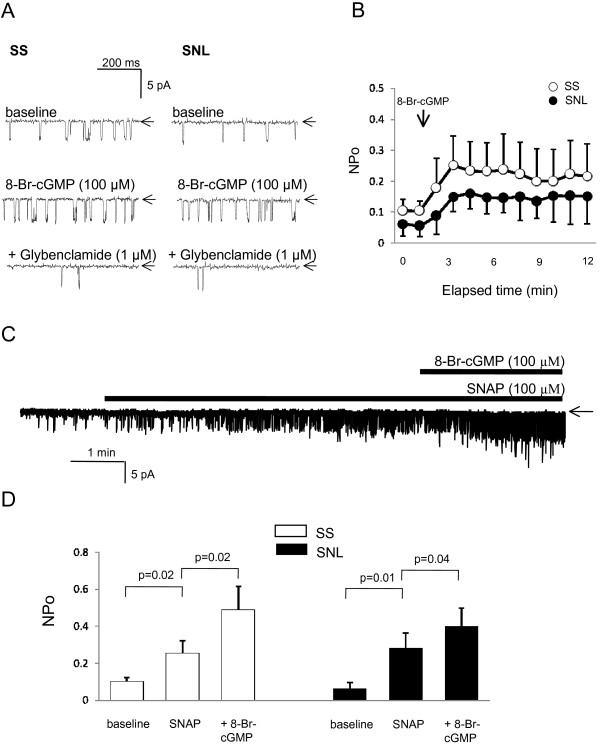

8-Br-cGMP activates KATP channels, but fails to mimic completely the activation induced by NO

KATP channels in cardiomyocytes, vascular or non-vascular smooth muscle cells, and pancreatic β cells are modulated by NO [52-56], indirectly via a classical cGMP-dependent pathway [52,53]. To investigate this pathway in large DRG neurons, we examined the effect of a membrane permeable cGMP analogue, 8-Br-cGMP, on neuronal KATP channel activity in cell-attached patch recordings. Similar to SNAP, bath application of 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM) significantly activated KATP channels in either SS neurons (NPo value 5 min after application of 8-Br-cGMP = 0.22 ± 0.08; n = 8; p = 0.002 vs. baseline) or SNL (NPo = 0.17 ± 0.06; n = 7; p = 0.001 vs. baseline) neurons. Subsequent addition of glybenclamide (1 μM) almost completely inhibited these currents (Figure 4A). Steady-state activation could be observed within only 2–3 minutes after exposure to 8-Br-cGMP (Figure 4B). When 8-Br-cGMP was applied after SNAP-induced steady-state activation had occurred (at least 5 min after SNAP), additional further channel opening was observed, both in SS neurons (n = 5; p = 0.02 vs. SNAP alone) and in SNL neurons (n = 5; p = 0.04 vs. SNAP alone) (Figure 4D). These data imply that NO does not activate KATPchannels via a cGMP-dependent PKG pathway, but via an alternative pathway. In order to examine the role of endogenous cGMP in activating KATP channels, we also tested the effect of zaprinast, a specific PDE inhibitor, in cell-attached recordings. In these experiments, zaprinast had no effect on KATP channel activity either in control neurons (n = 5; p = 0.88 vs. baseline), or in SNL neurons (n = 4; p = 1.0 vs. baseline) (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Effects of 8-Br-cGMP on KATP channel activity in DRG neurons. (A) Representative current traces in SS and SNL neurons recorded from cell-attached configuration at a holding potential of -60 mV. Bath application of 8-Br-cGMP, a membrane-permeable analogue of cGMP, increased KATP current in either SS or SNL neurons. Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) Time dependent of 8-Br-cGMP-induced channel activation (NPo) during cell-attached recording, indicating the elapsed time to peak effect. Each point represents 8 SS and 7 SNL neurons. (C) Additional effect of 8-Br-cGMP on SNAP (100 μM)-induced steady-state KATP currents in SS neurons. Changes of NPo values in either SS or SNL neurons are summarized in (D). Each vertical bar represents measurements from 5 patches (mean ± SD).

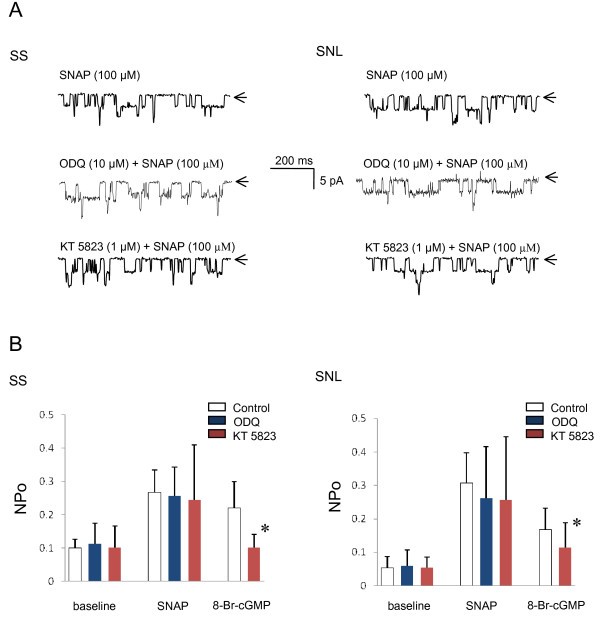

Effects of inhibitors of the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway on NO-induced KATP channel activation

To further investigate whether NO activates KATP currents via the classical NO/sGC/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway, we tested the effects of ODQ, a selective inhibitor of sGC, or the effects of KT 5823, a selective inhibitor of PKG, on SNAP-induced KATP channel activity in large SS or SNL DRG neurons, using the cell-attached patch-clamp configuration.

Pretreatment with ODQ (10 μM) for 20 min failed to inhibit SNAP-induced KATP channel activation in both SS neurons (NPo 10 min after SNAP = 0.25 ± 0.09; n = 6; p = 1.0 vs. control) and SNL neurons (NPo 10 min after SNAP = 0.27 ± 0.16; n = 6; p = 1.0 vs. control; Figure 5A, B). Similarly, pretreatment with KT 5823 (1 μM) for 20 min did not block SNAP-induced KATP channel activation in either SS neurons (NPo 10 min after SNAP = 0.14 ± 0.17; n = 5; p = 1.0 vs. control) or SNL neurons (NPo 10 min after SNAP = 0.26 ± 0.19; n = 6; p = 1.0 vs. control; Figure 5A, B). These results suggest that NO activates KATP channels via mechanism(s) other than the NO/cGMP/PKG pathway. Pretreatment with KT 5823 significantly reduces 8-Br-cGMP-induced KATP channel activation in both SS neurons (n = 8; p < 0.001 vs. control) and SNL neurons (n = 6; p < 0.001 vs. control). These findings indicate that 8-Br-cGMP activates KATP channels in both SS and SNL neurons via the activation of PKG. In inside-out patches, neither ODQ nor KT 5823 had any direct effect on KATP channels (n = 4; p = 0.823 or n = 4; p = 0.295 vs. control, respectively).

Figure 5.

Effects of NO/cGMP/PKG pathway inhibitors on NO-induced KATP channel activity in DRG neurons. (A) Representative traces of KATP currents in cell-attached patches at -60 mV holding potential from SS or SNL neurons. SNAP (100 μM) activated channel opening (upper traces). Activating effect of SNAP was not inhibited by pretreatment for at least 20 min with neither ODQ (10 μM), a specific sGC inhibitor (middle traces), or KT5823 (1 μM), a PKG inhibitor (lower traces), in either SS or SNL neurons. Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) Changes of NPo values obtained during baseline, after application of SNAP (100 μM), or 8-Br-cGMP (100 μM) with or without pretreatment of inhibitor in SS or SNL neurons. Each vertical bar represents measurements from 5–6 patches (mean ± SD).

Direct effect of NO on KATP channels in excised inside-out patches

To test the possibility of a direct effect of NO on KATP channels in large DRG neurons, we next examined its effects of SNAP in excised inside-out patches under cell-free conditions (Figure 6A). When the patch was excised into a nucleotide-free solution, marked current activity was observed. This current was inhibited by [ATP]i 1 mM or 10 μM in a concentration-dependent fashion. In the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i, subsequent application of SNAP (100 μM) gradually activated KATP channel (n = 6; p = 0.02 vs. baseline). However, in the presence of 10 μM [ATP]i, SNAP did not produce any significant channel activation (n = 6; p = 0.88 vs. baseline). These results indicate that direct KATP channel activation by NO is [ATP]i-dependent.

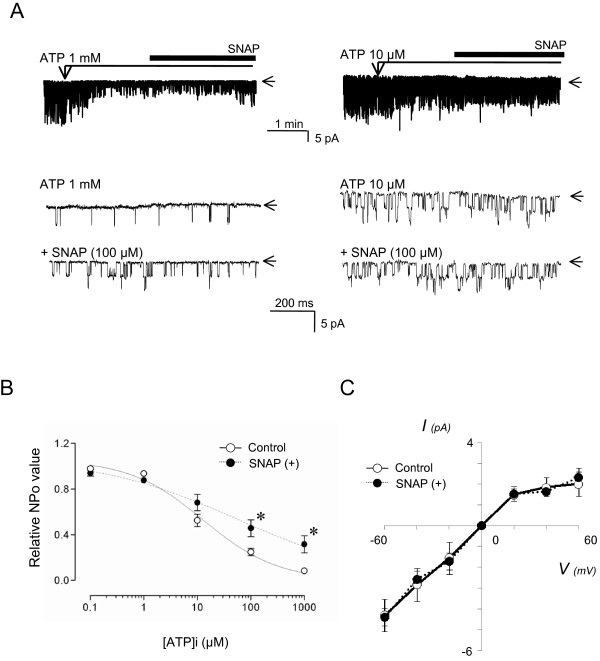

Figure 6.

Direct effects of NO on KATP channel activity in SS DRG neurons. (A) Representative current traces of KATP channel activity in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential excised from SS neurons. Bath application of SNAP (100 μM) activated KATP channel only in the presence of 1 mM, but not 10 μM [ATP]i. Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) Concentration-response relationship between [ATP]i (0–1000 μM) and relative NPo in the presence or absence of SNAP in inside-out patches. The relative NPo values were calculated by dividing the channel activity (expressed as NPo) in the presence of various [ATP]i with the activity in the absence of ATP. Each point represents measurements from 5–6 patches (mean ± SD). *: indicate significant difference from control. (C) Current-voltage relations were plotted from inside-out recordings of single KATP currents in the presence or absence of SNAP (100 μM) at membrane potentials between -60 and +60 mV (n = 5 each). Application of SNAP to patches did not affect single channel conductance.

We next tested the reciprocal interaction by testing whether NO-donor SNAP alters the ATP-sensitivity of KATP channels. In the presence or absence of SNAP, various ATP concentrations (0 – 1000 μM) were applied in excised patches whereupon KATP channel was suppressed in variable degrees (Figure 6B). [ATP]i, at concentrations = 100 μM, was less able to suppress KATP channel activation in the presence of SNAP. Altered ATP sensitivity was evident by the five-fold rightward shift of the IC50 value for [ATP]i from 12.8 μM (n = 7) to 54.4 μM (n = 7). Baseline current amplitude and conductance of channels in SS neurons remained unchanged during patch exposure to 100 μM SNAP (n = 5 each, p = 0.59; Figure 6C). Similar direct effects of SNAP on ATP sensitivity and current amplitude/voltage relationship were also observed in SNL neurons (data not shown).

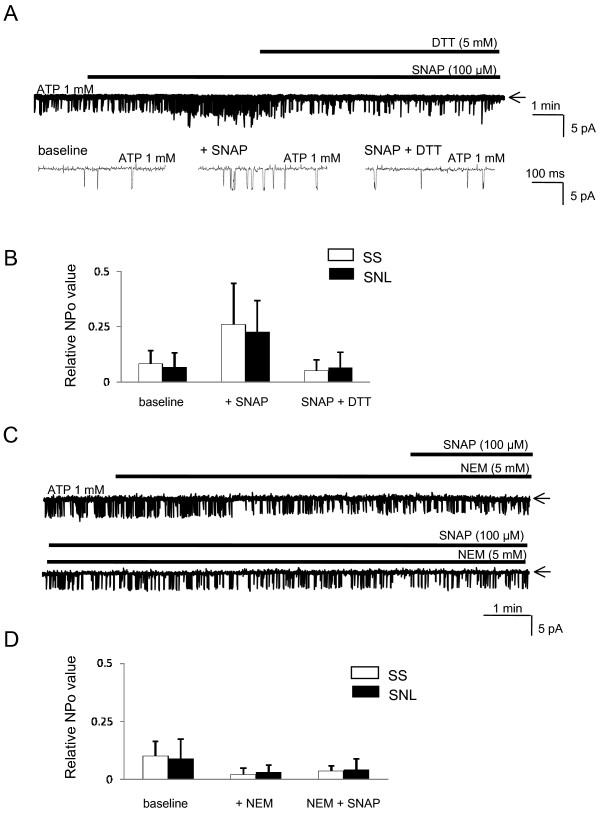

A known alternative pathway for biological effects of NO is by direct S-nitrosylation of the critical cysteine thiol group(s) of target proteins [1]. To test whether this pathway is involved in direct modulation of KATP channels by NO, we examined the effects of DTT, a thiol-specific reducing agent that reduces the nitrosylation by NO, on direct KATP channel activation by SNAP. SNAP-induced KATP channel activation in SS neurons in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i was completely reversed by subsequent bath application of DTT (5 mM) (n = 7, p = 0.009; Figure 7A). In inside-out patches, DTT alone had no direct effect on KATP channel (n = 5, p = 1.0 vs. baseline). Similar results were also observed in SNL neurons (n = 7, p = 0.01; Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

Effects of thiol-modifying agents on NO-induced KATP channel activation. (A) Representative current traces in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i in large SS neurons. SNAP (100 μM) and DTT (5 mM), a thiol-reducing agent, were added to bath solution as indicated by the horizontal solid bars. Arrows indicate closed channel state. The changes of NPo values are summarized in (B). Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 7 in each group). (C) Representative current traces in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i in large SS neurons. NEM (5 mM), a thiol alkylating agent, and SNAP (100 μM) were added to bath solution as indicated by the horizontal solid bars. Arrows indicate closed channel state. The changes of NPo values are summarized in (D). Values are shown as mean ± SD (n = 6 in each group).

To further test the possibility of S-nitrosylation by NO, we next tested the effects of NEM, which is known to covalently modify protein sulphhydryl groups making them incapable of nitrosylation, on SNAP-induced KATP channel activation. Bath application of NEM (5 mM) to inside-out patches in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i significantly decreased the basal channel activity (n = 6, p = 0.03 vs. baseline; Figure 7C). Presence of NEM completely eliminated the activating effect of SNAP on KATP channels (n = 6, p = 1.0 vs. before SNAP; Figure 7D). Similar results were also observed in SNL neurons (n = 6, p = 1.0 vs. before SNAP; Figure 7D). These findings suggest that SNAP effects are most probably mediated via a redox switch, involving direct S-nitrosylation of KATP channels. Furthermore, these direct actions of SNAP on KATP channels were not altered by SNL, suggesting that the ability for S-nitrosylation to KATP channel is preserved following nerve injury.

Site of action of NO on recombinant KATP channels expressed in COS7 cells

To determine the site of action of NO on KATP channels, we investigated the effect of SNAP in inside-out recordings from cloned SUR1/Kir6.2 channels, the predominant KATP channel in DRG neurons [57], heterologously expressed in COS7 cells. Transfected cells were identified by GFP co-transfection.

We first investigated whether the effect of NO on cloned SUR1/Kir6.2 mimicked the NO effect on native KATP channels in large DRG neurons. When the patch was excised into a low [ATP]i (0.1 μM) solution, recombinant SUR1/Kir6.2 channels showed marked current increases (Figure 8A; upper trace), that were strongly inhibited by 1 mM [ATP]i, confirming expression of functional KATP channels. Subsequent addition of SNAP 1 mM into the bath significantly activated SUR1/Kir6.2 channels (n = 7, p < 0.001) in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figure 8B). These currents were almost completely suppressed by DTT (5 mM) (p < 0.001).

Figure 8.

Direct effect of NO on wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 and truncated Kir6.2ΔC36 channels expressed in COS-7cells. (A) Representative current traces of wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 currents in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential. In the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i, bath application of SNAP (1 mM) activated wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 channel. Activation was suppressed by the subsequent application of the thiol-reducing agent, DTT (5 mM). Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) The concentration-dependent wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 channel activity (NPo) on SNAP. Each point represents measurements from 7 patches (mean ± SD) *: indicate significant difference from baseline. (C) Representative traces of current via truncated Kir6.2ΔC36 channels in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential. In the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i, bath application of SNAP (1 mM) did not significantly activate truncated Kir6.2ΔC36 currents (in contrast to wild type SUR1/Kir6.2 currents shown in Figure 8A). Arrows indicate closed channel state. (D) Summary of SNAP effects on relative channel activity of wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 currents and truncated Kir6.2ΔC36 channels, derived from experiments shown in Figure 8A and C. Each vertical bar represents measurements from 6–7 patches (mean ± SD).

We next explored whether the site at which NO interacts with the KATP channel lies on the regulatory (SUR1) or the pore-forming (Kir6.2) subunit, using a truncated isoform of Kir6.2 (Kir6.2ΔC36) that produces functional channels independently of SUR1 [58]. SNAP 1 mM fails to activate Kir6.2ΔC36 currents (n = 6, p = 1.0) in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i (Figure 8C and 8D). This observation, in contrast to activation of wild type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels, indicates that NO interacts with the SUR1 subunit, rather than the Kir6.2 subunit.

Effects of cysteine mutation within nucleotide-binding domain of SUR1

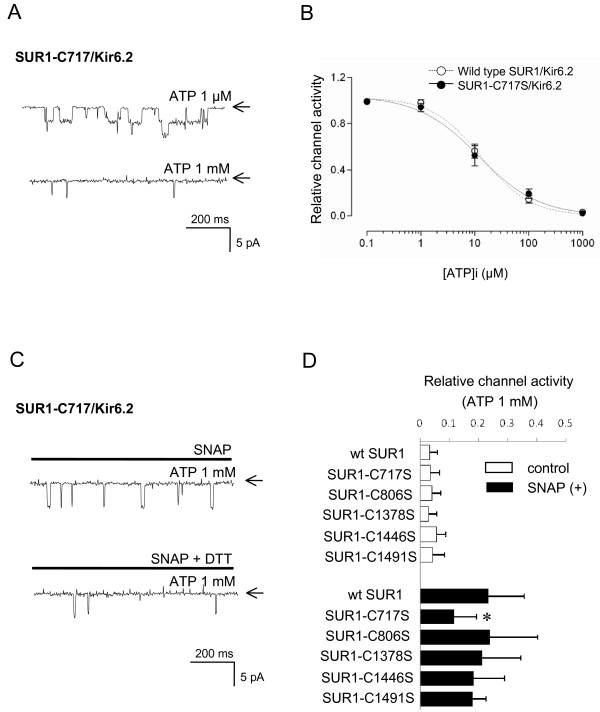

The [ATP]i-dependent modulation of native KATP channel by NO (Figure 6B) suggests that cysteine residues reacting with NO might be located at ATP-binding sites of SUR1 subunit; specifically within NBD1 and/or NBD2. In addition, the highly conserved Walker A (ATP-binding) motifs of SUR1 contain one single cysteine residue, at position 717 (C717) in NBD1. The ability of a thiol-modifying (alkylating) agent, NEM, (which inhibits native KATP channels), to prevent ATP binding at NBD1 is abolished by mutation of C717 [59]. This implies that cysteine at position C717 may be redox-active. We therefore focused on this cysteine residue, and examined the effect of mutating C717 to serine (C717S) on the sensitivity of the cloned SUR1/Kir6.2 channel to NO.

A patch containing recombinant SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels, also showed marked current increases when excised into a low [ATP]i (0.1 μM) solution (Figure 9A). These currents were strongly inhibited by 1 mM [ATP]i (n = 7, p < 0.001). The ATP-sensitivity of SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels (IC50 = 13.1 μM, n = 7) was not significantly different from that of wild type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels (IC50 = 11.6 μM, n = 7). Similar to the response of wild type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels, bath application of 1 mM SNAP significantly activated the SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channel in the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i. However SNAP was significantly less potent in activating the SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channel compared with the wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 channel (n = 8, p < 0.02 vs. wild type; Figure 9C). SNAP-induced SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channel activation was reversed by DTT (5 mM) (n = 7).

Figure 9.

Effects of mutations within nucleotide-binding domain of SUR1 on channel activation by NO. (A) Representative traces of currents via SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential. Bath application of ATP (1 mM) inhibited SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels. Arrows indicate closed channel state. (B) Concentration-response relationship curves between [ATP]i and relative NPo values for wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 or SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels. The relative channel activities were calculated by dividing the channel activity in the presence of various [ATP]i with the activity in the absence of ATP. Each point represents measurements from 7 patches (mean ± SD). (C) Representative current traces of SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channel currents in inside-out patches at -60 mV holding potential. In the presence of 1 mM [ATP]i, bath application of SNAP (1 mM) activated SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channel, but less than wild-type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels. Activation of these currents was suppressed by the subsequent application of a thiol-reducing agent, DTT (5 mM). Arrows indicate closed channel state. (D) Summary of ATP-sensitivity and SNAP effects on relative NPo values of wild-type (control) and mutated SUR1/Kir6.2 currents. The relative channel activities were calculated by dividing the channel activity in the presence or absence (1 mM [ATP]i only) of SNAP (100 μM) with the activity in the absence of ATP. Each horizontal bar represents measurements from 7–8 patches (mean ± SD).

In addition to C717S, we further examined the activating effects of NO after mutating the cysteine residues within NBD1 and NBD2 to serine, including those cysteine residues adjacent to C717 within NBD1 (C806S), and all three cysteine residues within NBD2 (C1378, C1446, C1491). All these mutated channels showed similar ATP-sensitivity (Figure 9D, controls). Among these mutants, only SUR1-C717S/Kir6.2 channels significantly affected NO-sensitivity compared with wild type SUR1/Kir6.2 channels.

Discussion

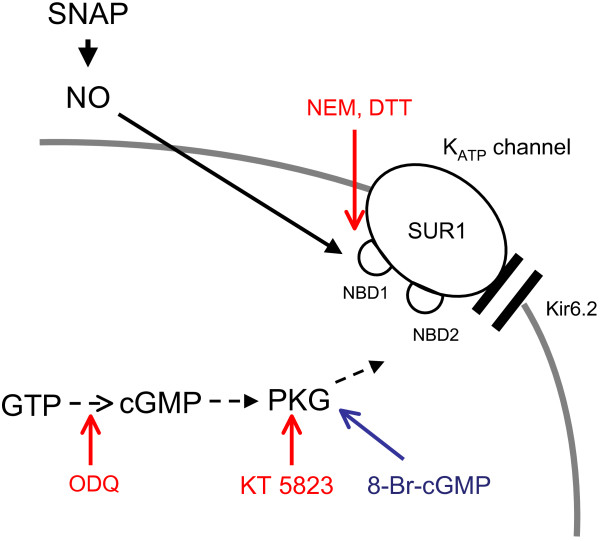

Our findings demonstrate that NO activates KATP channels in mammalian sensory neurons. We additionally showed that inhibition of sGC and PKG fails to block the activation by NO, indicating that NO signaling is not through the classical indirect pathway (Figure 10). NO-induced activation of KATP channels also occurs in cell-free patches, showing that cytosolic elements are not needed for NO action. However, NO activation of KATP current is inhibited by thiol-reducing or thiol-alkylating agents, which demonstrates that S-nitrosylation is needed for NO action (Figure 10). Since NO fails to activate current conveyed by Kir6.2 channels that lack SUR1, the NO effect must be sited on the SUR1 subunit. Mutagenesis of cysteine residues within SUR1 limits NO-induced KATP channel activation, confirming SUR1 as the site of S-nitrosylation. Taken together, these novel findings prove that NO activates KATP channels via S-nitrosylation of one or more cysteine residues on the SUR1 subunit (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Possible pathways involved in KATP channel activation by NO and sites of action of modulators. SNAP exogenously releases NO that might have activated sGC by diffusion into the cytosol. sGC in other tissues generates endogenous cGMP, which may further activate PKG in order to produce downstream effects on the channel. However, the results of this study imply that sGC is not active in DRG neurons. Dashed arrows indicate also that the indirect NO/sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway is not active in DRG neurons, because ODQ, a specific sGC inhibitor, and KT 5823, a specific PKG inhibitor, fail to block it (red arrows). In contrast, exogenous membrane permeable 8-Br-cGMP (blue arrow) activates KATP channels via PKG. Solid arrow indicates that NO most likely activates KATP channels via S-nitrosylation on the NBD1 within the SUR1 subunit. This direct pathway is prevented by thiol-alkylating, or reversed or thiol-reducing agents (NEM or DTT, respectively; red arrow).

Although the sGC/cGMP/PKG pathway mediates NO regulation of KATP channels in cardiomyocytes, vascular and non-vascular smooth muscle cells, and pancreatic β cells [52-56], this is not the case in DRG neurons. Our finding that NO/sGC/cGMP is inactive in DRG cells is consistent with reports indicating the absence of sGC in mice [45] and cGMP in rat DRG neurons [46] using immunohistochemical techniques. However, our data show that an exogenous membrane permeable cGMP analogue still activates KATP channels via a PKG-dependent mechanism, as in other tissues [53,60]. The presence of PKG in DRG neurons that lack an up-stream NO/sGC/cGMP pathway suggests an alternative pathway of activation, perhaps via natriuretic peptide receptor-B stimulation [45]. PKG expression is not altered by axotomy [61], possibly explaining our findings of similar PKG-dependent 8-Br-cGMP actions in both control and axotomized neurons.

As an alternative to the indirect cGMP-signaling pathway, NO can also directly modify proteins by S-nitrosylation, through which S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) are formed by covalent addition of an NO moiety (formally as NO+) to cysteine residues. S-nitrosylation signaling underlies NO modification of many ion channels, including the NMDA receptor-channel complex, Ca2+-activated K+ channels, Na+ channels in baroreceptors, cardiac Ca2+ release channels, and olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels [1,62-65]. Changes in the thiol-redox status of cysteine residues by thiol-group-modifying substances are also involved in NO modulation of KATP channels in pancreatic β cells, cardiomyocytes, and skeletal muscle cells [66-68]. Our new observation adds sensory neurons as a site at which S-nitrosylation of cysteines on the KATP channel activates the KATP currents.

In contrast to our findings, NO has no direct effect on native cardiac and pancreatic KATP channels [53,55]. Although the mechanisms determining susceptibility to S-nitrosylation by NO remain unknown, access of NO to available cysteine targets is determined by peptide tertiary structures and associated proteins [1]. Also, the number and location of cysteines may vary between KATP channels of different subunit compositions [20].

As in native KATP channels, we showed that NO directly activates cloned SUR1/Kir6.2 channels expressed in COS7 cells, although this effect is approximately 3-fold less potent than in native channels. Compared to SUR1/Kir6.2 expressed in DRG neurons [57], the decreased sensitivity of channels in COS7 cells to NO may reflect differences in technique (inside-out recordings from cloned channels, cell-attached from native KATP channels), or variations in the redox status of the cytosolic environment, and different protein conformation in the two experimental models. Despite these differences, we observed direct modulation of KATP channels by NO in both settings.

Previous studies using mutagenesis have revealed that thiol-reagents modify KATP channel activity by interacting with a single cysteine residue at either Kir6.2 or SUR1. Oxidizing agents pCMPS and MTSET interact with a specific single cysteine residue on Kir6.2, whereas the alkylating agent NEM interacts with a cysteine residue on SUR1 [59,69,70]. In the present study, NO failed to modulate Kir6.2 channels lacking SUR1, indicating that NO does not act on a thiol oxidizing-sensitive site on Kir6.2, but that the critical cysteine residue is on the SUR1.

Nucleotides regulate KATP channel activity in a complex fashion. The channel is inhibited by ATP binding to Kir6.2, whereas the channel is activated by Mg-nucleotides (MgATP, MgADP) interacting with the two NBDs on SUR1 [20-22]. Thus [ATP]i-dependence of activation of native KATP channels by NO suggests that the target cysteine is located at the NBDs within SUR1. Furthermore, our site-directed mutagenesis demonstrated that only mutation of cysteine residue at position 717 (C717) within NBD1 significantly inhibited the activation by NO. Cys717 is the sole cysteine residue located on the highly conserved Walker A (ATP-binding) motifs of SURI. Because the alkylating agent NEM directly interacts with this residue [59], it is likely that cysteine nitrosylation by NO modulates nucleotides-SUR1 interaction, resulting in allosteric activation of the KATP channel. Mutation of Cys717 did not completely inhibit the NO-induced channel activation, suggesting that other cysteine residues besides those in the NBD may be involved in NO action via poly-nitrosylation, as has been shown in cardiac calcium release channel [65].

The significance of the KATP channel activation by NO in DRG neurons is presently unknown. If DRG neurons lack sGC and the capacity to mobilize the NO/sGC/cGMP pathway, it is likely that S-nitrosylation is the only mechanism by which NO activates KATP channels in these cells. nNOS expression in DRG neurons is markedly up-regulated after injury, especially in the small and medium sized neuronal population, enabling these neurons to produce endogenous NO [50,51]. Additionally, glial satellite cells also produce and release NO. Since this molecule is highly diffusible, NO from this sources may influence KATP channels predominantly expressed in large DRG neurons. The direct S-nitrosylation pathway requires higher NO levels and responds more slowly than the indirect pathway, and thereby producing a threshold effect by which KATP channels would respond only to intense NO stimuli and only in a prolonged temporal domain [1].

Our present data confirm our previous findings of KATP current loss following nerve injury [25,35]. Since axotomy does not alter the channel biophysical properties or sensitivity to modulators, loss of KATP current may be the result of regulatory shifts that reduce KATP channel opening. An implication of our findings is that decreased channel opening after axotomy may be driven by diminished NO levels, but this needs to be confirmed by further studies. Our results also suggest that KATP channel modulation by S-nitrosylation signaling is not altered by injury. Our present data show that activation by NO restores the KATP current in axotomized neurons. Since KATP currents decrease neuronal excitability and diminish excitatory neurotransmission, it is likely that elevation of channel opening by NO may produce analgesic effects even in conditions in which there is no preceding deficit of KATP currents. We did not directly assess any attenuation in neuronal excitability mediated by increased activity of KATP channels following application of NO, and this may be a limitation of this study. However, NO-regulation explains why some drugs exert peripheral analgesic effects via NO-related pathways that activate peripheral neuronal KATP channels [15,17-19,39]. Our findings, along with previous studies, demonstrate that NO mediated activation of KATP channels might be employed as a pathway for therapy against pain.

Conclusion

NO exogenously released by the NO donor SNAP activates KATP channels in DRG neurons. This activation is not altered by painful-like nerve injury. Effects mediated by NO do not involve the indirect sGC/cGMP/PKG signaling pathway, but may be the consequence of direct S-nitrosylation of cysteine residue(s) on SUR1 subunits associated with ATP-binding site.

Methods

Approval of experimental procedures

All procedures in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Animal Surgery

For all experiments, we used Male Sprague-Dawley rats (125–160 g), 6 weeks old and weighing 125–160 g, which were obtained from a single vendor (Taconic Inc., Germanville, NY). We randomly assigned rats to a surgical axotomy group using the spinal nerve ligation (SNL) model [71], or to a control group that received sham skin operation (SS). We anesthetized rats with isoflurane (1.5–3% in oxygen) by spontaneous ventilation. We exposed the right lumbar paravertebral area through a lumbar incision, accessed the fifth (L5) and sixth (L6) lumbar nerves, which we ligated with 6-0 silk ligature, and transected distal to the ligature. We then closed the lumbar fascia with 4-0 absorbable vicryl polyglactin suture, and the skin with three to five surgical staples. Unlike the originally described method [71], we did not excise the paraspinous muscles or the adjacent articular processes. In control rats, we performed sham operation by lumbar skin incision and closure by staples only.

Behavioral testing

We selected rats that successfully developed neuropathic pain behavior using a previously validated [72] and reported method [73] that identifies hyperalgesia after SNL with high specificity. We tested animals on the 10th, 12th, and 14th postoperative days onto a 0.25 in. wire grid. Briefly, after 30 min's rest, we touched the hind paws randomly using a 22-gauge spinal needle with pressure adequate to indent but not penetrate the skin (to a total of ten applications per session). Rats subjected to SS operation exhibited normal, brief reflexive withdrawal responses and were used as controls. Rats that displayed a probability of hyperalgesia-type response (> 2 s sustained lifting, licking, chewing, or shaking of the paw) at least 20% averaged over 3 test days, and normal contralateral responses after SNL, were considered as responders with neuropathic behavior after SNL. Behavioral testing was repeated on the day of study to confirm the presence of hyperalgesia. We further included only these responding rats in our study, in comparison with controls.

Cell isolation and plating

We harvested control (L4 and L5) or axotomized (L5) ganglia, from control (SS) or hyperalgesic rats (SNL) respectively, between the 17th and 28th postoperative days. We sacrificed animals by decapitation under deep isoflurane anesthesia, excised ganglia through a lumbar incision, and at the same time confirmed accuracy of initial surgery.

For patch-clamp recordings, we placed excised DRG into separate 35 mm Petri dishes containing cold, oxygenated, Hanks Balanced Salt Solution (Gibko, Invitrogen, Grand Islan, NY), and minced them with iris scissors. We dissociated ganglia enzymatically in a solution containing 0.25 ml 0.05% w:v liberase blendzyme 2 (Roche Diagnostics Corp., Indianapolis, IN) and 0.25 ml DMEM/F12 with glutaMAX (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium F12; Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) in an incubator at 37°C for 30 min. We then removed the supernatant after centrifugation and re-incubated cells at 37°C for another 30 min in 0.2 ml 0.0625% trypsin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and 0.0125% deoxyribonuclease 1 (150,000 U, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in 0.25 ml DMEM. We then isolated cells by centrifugation (600 rpm for 5 min) after adding 0.25 ml trypsin inhibitor 0.1% w:v (Sigma St. Louis, MO), and re-suspended them in a culture medium consisting of 0.5 mM glutamine, 0.02 mg/ml gentamicin (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), 100 ng/ml nerve growth factor 7S (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), 2% (vol/vol) B-27 supplement (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA), and 98% (vol/vol) neural basal medium A (Gibco, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA). Finally, we plated cells onto poly-l-lysine-coated 12-mm glass coverslips (Deutsche Spiegelglas; Carolina Biologic Supply, Burlington, NC), kept them in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 95% air and 5% CO2, and studied them within 3–8 h of dissociation.

Molecular Biology and Transfection

KATP channel-deficient COS7 cells were plated at a density of 3 × 105/dish (35 mm in diameter) and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Rat Kir6.2 (GenBank X97041) and rat SUR1 (GenBank X97279) cDNAs were used for expression study. A truncated form of Kir6.2 lacking the last 36 amino acids at the C-terminus was obtained by polymerase chain reaction amplification. Polymerase chain reaction products were cloned into the pCR3.1 vector by using the TA cloning system (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then cloned into the pcDNA3.1 (-) vector (Invitrogen Corp.) for mammalian expression. Point mutation of cysteine at position 717 (C717), C806, C1378, C1446, and C1491 within SUR1 to serine (C717S, C806S, C1378S, C1446S, and C1491S) was performed by using the Site-Directed Mutagenesis system (Invitrogen Corp.). All cDNA products were sequenced by using the BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit and an ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to confirm the sequence. A full-length Kir cDNA and a full-length SUR cDNA were subcloned into the mammalian expression vector pcDNA3.1 (-). For electrophysiological recordings, either wild-type or mutated pcDNA3.1 (-) Kir6.2 alone (1 μg), or pcDNA3.1 (-) Kir6.2 (1 μg) plus pcDNA3.1 (-) SUR1 (3 μg) were transfected into COS7 cells with green fluorescent protein cDNA as a reporter gene by using lipofectamine and Opti-MEN 1 reagents (Life Technologies Inc., Rockville, MD) according to the manufacturer's instructions. After transfection, cells were cultured at 37°C with 95% air and 5% CO2 for 48–72 h before being subjected to electrophysiological recordings.

Measurement of intracellular ATP concentration

For measuring intracellular ATP concentration, we extracted intracellular ATP ([ATP]i) using ATP extraction kit (Toyo Ink, Tokyo, Japan). After preincubation in HBS for 30 min, we incubated DRG neurons in the presence or absence of 100 μM SNAP for 10 minutes. We quantitatively measured the [ATP]i level using the luciferin-luciferase assay solution (Toyo Ink), according to protocols provided by the manufacturer.

Electrophysiological recordings

We visualized plated neurons using an inverted Nikon Diaphot 300 microscope with Hoffman modulation optic system. We selected only large diameter neuronal somata (≥ 40 μm in diameter) because we have previously shown that only these develop KATP current alterations [35], as well as changes indicative of increased excitability after painful-like nerve injury by SNL [74]. Large neuronal somata, roughly correspond to large, myelinated Aβ fibers.

We recorded current passing through single channels in inside-out or cell-attached patch configurations. In cell-attached patches, both bath and pipette (extracellular) solutions were composed of the following: 140 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 5.5 mM dextrose, and 1 mM EGTA. In inside-out patches, the bath (intracellular) solution contained 140 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 1.5 mM EGTA and 5.5 mM dextrose. The pipette (extracellular) solution was of the same composition as that used in cell-attached recordings. The pH of all solutions was adjusted to 7.4 with KOH. Osmolality was adjusted approximately to 300 mOsm/l by adding sucrose if necessary. We pulled patch micropipettes from borosilicate glass capillaries using a Flaming/Brown micropipette puller, model P-97 (Sutter, San Rafael, CA) and flame polished them with a microforge polisher (Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) prior to use. Their resistance ranged between 3 and 6 MΩ when filled with the internal solution, and placed into the recording solutions.

We recorded single channel currents at room temperature (20–25°C) using an Axon CNS Multiclamp 700B amplifier, digitized them using an analog-to-digital converter (Axon CNS DigiData 1440A; Axon Instruments, Foster, CA), and stored them into a PC. Sampling frequency of single-channel data was 5 KHz with a low-pass filter (1 KHz). We used pClamp version 10.2 software (Axon Instruments) for data acquisition and analysis. We applied a conventional 50% current amplitude threshold level criterion to determine open events. Channel open probability (Po) was determined from the ratios of the area under the peaks in the amplitude histograms fitted by a Gaussian distribution. We calculated channel activity as NPo (where N is the number of observed channels in the patch) from data samples of either 30 s (in inside-out recordings), or 60 s (in cell-attached recordings), in the steady state. In inside-out recordings, NPo of the KATP channels was normalized to the baseline NPo value obtained before test drugs at bathing solution without ATP (indicating relative channel activity).

Drugs

SNAP, SNP, glybenclamide, L-NAME, zaprinast, ODQ, KT5823, 8-Br-cGMP, DTT, and NEM were purchased from Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA. SNAP was stored at -20°C as a 30 mM stock solution in methanol. The solution of SNAP was prepared 15 min before being tested experimentally, and was not used thereafter for longer than 2 hours. It was also continuously kept protected from light. Glybenclamide (10 mM) and ODQ (20 mM) were stocked in DMSO. SNP, L-NAME, DTT, and NEM were prepared as a 1 M, 10 mM, 0.5 M, and 50 mM stock solution in distilled water, respectively. All drugs were diluted in perfusate as indicated. Oxidized SNAP, that no longer generates NO, was prepared as described previously, by allowing SNAP dissolved in DMSO, to decompose at room temperature for 48 hours [47]. When added to the bathing solution, the maximal concentrations of either methanol (0.01%) or DMSO (0.01%) alone did not exert any affect, nor modify the KATP channel activity of the preparation. Glybenclamide [75], L-NAME [76], zaprinast [60], ODQ [77], KT5823 [60], DTT [62], and NEM [78] were applied at concentrations that have been previously reported as effective in inhibiting their respective targets.

Data Analysis and Statistics

Data are expressed as means ± SD. The effect of bath changes, indicative of various drug effects, was evaluated using repeated measures ANOVA to identify main effects, followed by Bonferoni post hoc tests whenever appropriate. Student's t-tests were also used for pair-wise comparisons, whenever needed. Significance was accepted at P < 0.05. Concentration-response curves were plotted by non-linear regression using sigmoidal concentration-response (variable slope) equations (Y = bottom/(1+10^(logEC50-X)*Hill slope), and statistically compared using the Prism software. The SPSS statistical software was used for statistical analysis.

Abbreviations

KATP: ATP-sensitive; DRG: dorsal root ganglion; NO: nitric oxide; SNL: spinal nerve ligation; SS: sham surgery; [ATP]I: intracellular ATP concentration; sGC: soluble guanylate cyclase; SUR: sulfonylurea receptor; Kir6.2: inwardly-rectifying potassium channel 6.2; NBD: nucleotide binding domain; nNOS: neuronal nitric oxide synthase; DNP: 2,4-Dinitrophenol; SNAP: S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine; SNP: sodium nitroprusside; L-NAME: NG-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester; ODQ: 1H-[1, 2, 4] oxadiazolo [4, 3-a] quinoxalin-1-one; 8-Br-cGMP: 8-bromo-cGMP sodium salt; DTT: di-thiothreitol; NEM: N-ethylmaleimide; DMSO: dimethyl sulfoxide.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TK, MK, and CDS carried out the electrophysiological experiments, data analysis and wrote the manuscript as well as interpreted data. VZ, MYL, HEW, and GG participated in the electrophysiological experiments in DRG neurons. TK, VZ, HEW, GG, and JBM carried out animal surgery and behavior testing. TK and MK carried out molecular biology and ATP content analysis. WMK, QHH, and CDS conceived the study, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

The work has been supported NINDS S049420A grant (CDS) and NIH NS42150 (QH).

Contributor Information

Takashi Kawano, Email: tkawano@mcw.edu.

Vasiliki Zoga, Email: vzoga@mcw.edu.

Masakazu Kimura, Email: roykawat@gmail.com.

Mei-Ying Liang, Email: liang@mcw.edu.

Hsiang-En Wu, Email: hwu@mcw.edu.

Geza Gemes, Email: ggemes@mcw.edu.

J Bruce McCallum, Email: mcallum@mcw.edu.

Wai-Meng Kwok, Email: wmkwok@mcw.edu.

Quinn H Hogan, Email: qhogan@mcw.edu.

Constantine D Sarantopoulos, Email: csar@mcw.edu.

References

- Ahern GP, Klyachko VA, Jackson MB. cGMP and S-nitrosylation: two routes for modulation of neuronal excitability by NO. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:510–517. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)02254-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Mancuso C, Calvani M, Rizzarelli E, Butterfield DA, Stella AM. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:766–775. doi: 10.1038/nrn2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Yaster M, Raja SN, Tao YX. Genetic knockout and pharmacologic inhibition of neuronal nitric oxide synthase attenuate nerve injury-induced mechanical hypersensitivity in mice. Mol Pain. 2007;3:29. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-3-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao JX, Xu XJ. Treatment of a chronic allodynia-like response in spinally injured rats: effects of systemically administered nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Pain. 1996;66:313–319. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)03039-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo ZD, Chaplan SR, Scott BP, Cizkova D, Calcutt NA, Yaksh TL. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase mRNA upregulation in rat sensory neurons after spinal nerve ligation: lack of a role in allodynia development. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9201–9208. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-21-09201.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meller ST, Gebhart GF. Nitric oxide (NO) and nociceptive processing in the spinal cord. Pain. 1993;52:127–136. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(93)90124-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa AM, Prado WA. The dual effect of a nitric oxide donor in nociception. Brain Res. 2001;897:9–19. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)01995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Shimoyama N. Role of nitric oxide in the development of thermal hyperesthesia induced by sciatic nerve constriction injury in the rat. Anesthesiology. 1995;82:1266–1273. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199505000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon YW, Sung B, Chung JM. Nitric oxide mediates behavioral signs of neuropathic pain in an experimental rat model. Neuroreport. 1998;9:367–372. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199802160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Eisenach JC. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase is upregulated in a subset of primary sensory afferents after nerve injury which are necessary for analgesia from alpha2-adrenoceptor stimulation. Brain Res. 2007;1127:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivancos GG, Parada CA, Ferreira SH. Opposite nociceptive effects of the arginine/NO/cGMP pathway stimulation in dermal and subcutaneous tissues. Br J Pharmacol. 2003;138:1351–1357. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tegeder I, Schmidtko A, Niederberger E, Ruth P, Geisslinger G. Dual effects of spinally delivered 8-bromo-cyclic guanosine mono-phosphate (8-bromo-cGMP) in formalin-induced nociception in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2002;332:146–150. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00938-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit RK, Bhargava VK. Neurotransmitter mechanisms in gabapentin antinociception. Pharmacology. 2002;65:198–203. doi: 10.1159/000064344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte ID, Ferreira SH. The molecular mechanism of central analgesia induced by morphine or carbachol and the L-arginine-nitric oxide-cGMP pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;221:171–174. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90789-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazaro-Ibanez GG, Torres-Lopez JE, Granados-Soto V. Participation of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP-ATP-sensitive K(+) channel pathway in the antinociceptive action of ketorolac. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;426:39–44. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01206-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WP, Hao JX, Ongini E, Impagnatiello F, Presotto C, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Xu XJ. A nitric oxide (NO)-releasing derivative of gabapentin, NCX alleviates neuropathic pain-like behavior after spinal cord and peripheral nerve injury. Br J Pharmacol. 8001;141:65–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves DP, Tatsuo MA, Leite R, Duarte ID. Diclofenac-induced peripheral antinociception is associated with ATP-sensitive K+ channels activation. Life Sci. 2004;74:2577–2591. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Soto V, Arguelles CF, Ortiz MI. The peripheral antinociceptive effect of resveratrol is associated with activation of potassium channels. Neuropharmacology. 2002;43:917–923. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(02)00130-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AR, Duarte ID. The peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by morphine is associated with ATP-sensitive K(+) channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:110–114. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seino S. ATP-sensitive potassium channels: a model of heteromultimeric potassium channel/receptor assemblies. Annu Rev Physiol. 1999;61:337–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.61.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki T, Seino S. Roles of KATP channels as metabolic sensors in acute metabolic changes. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:917–925. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols CG. KATP channels as molecular sensors of cellular metabolism. Nature. 2006;440:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature04711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi XX, Jiang X, Nicol GD. ATP-sensitive potassium currents reduce the PGE2-mediated enhancement of excitability in adult rat sensory neurons. Brain Res. 2007;1145:28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.01.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K, Inagaki N. Neuroprotection by KATP channels. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;38:945–949. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantopoulos C, McCallum B, Sapunar D, Kwok WM, Hogan Q. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in rat primary afferent neurons: the effect of neuropathic injury and gabapentin. Neurosci Lett. 2003;343:185–189. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(03)00383-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayden JE. Functional roles of KATP channels in vascular smooth muscle. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2002;29:312–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.2002.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soundarapandian MM, Zhong X, Peng L, Wu D, Lu Y. Role of K(ATP) channels in protection against neuronal excitatory insults. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1721–1729. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold MS. Spinal nerve ligation: what to blame for the pain and why. Pain. 2000;84:117–120. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann M. Pathobiology of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;429:23–37. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(01)01303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amir R, Kocsis JD, Devor M. Multiple interacting sites of ectopic spike electrogenesis in primary sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2576–2585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4118-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JN, Meyer RA. Mechanisms of neuropathic pain. Neuron. 2006;52:77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamata M, Omote K. Involvement of increased excitatory amino acids and intracellular Ca2+ concentration in the spinal dorsal horn in an animal model of neuropathic pain. Pain. 1996;68:85–96. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(96)03222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandrup T, Woolf CJ, Coggeshall RE. Delayed loss of small dorsal root ganglion cells after transection of the rat sciatic nerve. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:172–180. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(20000626)422:2<172::AID-CNE2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestergaard S, Tandrup T, Jakobsen J. Effect of permanent axotomy on number and volume of dorsal root ganglion cell bodies. J Comp Neurol. 1997;388:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971117)388:2<307::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantopoulos C, McCallum B, Liang M, Kwok WM, Hogan Q. Electrophysiological parameters specifically mediating neuropathic pain behavior after spinal nerve ligation in the rat. European Journal of Anaesthesiology. 2008;25 [Google Scholar]

- Cadiou H, Studer M, Jones NG, Smith ES, Ballard A, McMahon SB, McNaughton PA. Modulation of acid-sensing ion channel activity by nitric oxide. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13251–13260. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2135-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renganathan M, Cummins TR, Waxman SG. Nitric oxide blocks fast, slow, and persistent Na+ channels in C-type DRG neurons by S-nitrosylation. J Neurophysiol. 2002;87:761–775. doi: 10.1152/jn.00369.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves DP, Soares AC, Francischi JN, Castro MS, Perez AC, Duarte ID. Additive antinociceptive effect of the combination of diazoxide, an activator of ATP-sensitive K+ channels, and sodium nitroprusside and dibutyryl-cGMP. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;489:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs D, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. Peripheral analgesic blockade of hypernociception: activation of arginine/NO/cGMP/protein kinase G/ATP-sensitive K+ channel pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3680–3685. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares AC, Duarte ID. Dibutyryl-cyclic GMP induces peripheral antinociception via activation of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in the rat PGE2-induced hyperalgesic paw. Br J Pharmacol. 2001;134:127–131. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain NK, Patil CS, Singh A, Kulkarni SK. Sildenafil-induced peripheral analgesia and activation of the nitric oxide-cyclic GMP pathway. Brain Res. 2001;909:170–178. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02673-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscheweyh R, Goralczyk A, Wunderbaldinger G, Schober A, Sandkuhler J. Possible sources and sites of action of the nitric oxide involved in synaptic plasticity at spinal lamina I projection neurons. Neuroscience. 2006;141:977–988. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maihofner C, Euchenhofer C, Tegeder I, Beck KF, Pfeilschifter J, Geisslinger G. Regulation and immunhistochemical localization of nitric oxide synthases and soluble guanylyl cyclase in mouse spinal cord following nociceptive stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 2000;290:71–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01302-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess GM, Mullaney I, McNeill M, Coote PR, Minhas A, Wood JN. Activation of guanylate cyclase by bradykinin in rat sensory neurones is mediated by calcium influx: possible role of the increase in cyclic GMP. J Neurochem. 1989;53:1212–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb07417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtko A, Gao W, Konig P, Heine S, Motterlini R, Ruth P, Schlossmann J, Koesling D, Niederberger E, Tegeder I, et al. cGMP produced by NO-sensitive guanylyl cyclase essentially contributes to inflammatory and neuropathic pain by using targets different from cGMP-dependent protein kinase I. J Neurosci. 2008;28:8568–8576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2128-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi TJ, Holmberg K, Xu ZQ, Steinbusch H, de Vente J, Hokfelt T. Effect of peripheral nerve injury on cGMP and nitric oxide synthase levels in rat dorsal root ganglia: time course and coexistence. Pain. 1998;78:171–180. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasukawa T, Tokunaga E, Ota H, Sugita H, Martyn JA, Kaneki M. S-nitrosylation-dependent inactivation of Akt/protein kinase B in insulin resistance. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7511–7518. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clementi E, Brown GC, Feelisch M, Moncada S. Persistent inhibition of cell respiration by nitric oxide: crucial role of S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial complex I and protective action of glutathione. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7631–7636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin CY, Choi JW, Ryu JR, Ryu JH, Kim W, Kim H, Ko KH. Immunostimulation of rat primary astrocytes decreases intracellular ATP level. Brain Res. 2001;902:198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(01)02385-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimi Y, Fujimura M, Vincent SR, Kimura H. Localization of NADPH-diaphorase-containing neurons in sensory ganglia of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1991;306:382–392. doi: 10.1002/cne.903060303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Verge V, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, Ju G, Bredt D, Synder SH, Hokfelt T. Nitric oxide synthase-like immunoreactivity in lumbar dorsal root ganglia and spinal cord of rat and monkey and effect of peripheral axotomy. J Comp Neurol. 1993;335:563–575. doi: 10.1002/cne.903350408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deka DK, Brading AF. Nitric oxide activates glibenclamide-sensitive K+ channels in urinary bladder myocytes through a c-GMP-dependent mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Kim N, Joo H, Kim E, Earm YE. ATP-sensitive K(+) channel activation by nitric oxide and protein kinase G in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;283:H1545–1554. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01052.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyoshi H, Nakaya Y, Moritoki H. Nonendothelial-derived nitric oxide activates the ATP-sensitive K+ channel of vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1994;345:47–49. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00417-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinbo A, Iijima T. Potentiation by nitric oxide of the ATP-sensitive K+ current induced by K+ channel openers in guinea-pig ventricular cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:1568–1574. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuura Y, Ishida H, Hayashi S, Sakamoto K, Horie M, Seino Y. Nitric oxide opens ATP-sensitive K+ channels through suppression of phosphofructokinase activity and inhibits glucose-induced insulin release in pancreatic beta cells. J Gen Physiol. 1994;104:1079–1098. doi: 10.1085/jgp.104.6.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoga V, Liang MY, Kawano T, Gemes G, Wu HW, Abram S, Hogan Q, Sarantopoulos C. Morphological disrribution of sulfonylurea receptor 1 (SUR1) in peripheral sensory neurons: the effect of nerve injury. Society for Neuroscience 2008 Meeiting; Washington, DC. 2008.

- Tucker SJ, Gribble FM, Zhao C, Trapp S, Ashcroft FM. Truncation of Kir6.2 produces ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the absence of the sulphonylurea receptor. Nature. 1997;387:179–183. doi: 10.1038/387179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo M, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM, Amachi T, Ueda K. NEM modification prevents high-affinity ATP binding to the first nucleotide binding fold of the sulphonylurea receptor, SUR1. FEBS Lett. 1999;458:292–294. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai Y, Lin YF. Dual regulation of the ATP-sensitive potassium channel by activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456:897–915. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0447-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Chao DS, Santillano DR, Cornwell TL, Nairn AC, Greengard P, Lincoln TM, Bredt DS. cGMP-dependent protein kinase in dorsal root ganglion: relationship with nitric oxide synthase and nociceptive neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:3130–3138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-10-03130.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broillet MC, Firestein S. Direct activation of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel through modification of sulfhydryl groups by NO compounds. Neuron. 1996;16:377–385. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YB, Tenneti L, Le DA, Ortiz J, Bai G, Chen HS, Lipton SA. Molecular basis of NMDA receptor-coupled ion channel modulation by S-nitrosylation. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:15–21. doi: 10.1038/71090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Chapleau MW, Bates JN, Bielefeldt K, Lee HC, Abboud FM. Nitric oxide as an autocrine regulator of sodium currents in baroreceptor neurons. Neuron. 1998;20:1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L, Eu JP, Meissner G, Stamler JS. Activation of the cardiac calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) by poly-S-nitrosylation. Science. 1998;279:234–237. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5348.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzee WA, Nakamura TY, Faivre JF. Effects of thiol-modifying agents on KATP channels in guinea pig ventricular cells. Am J Physiol. 1995;269:H1625–1633. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.5.H1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam MS, Berggren PO, Larsson O. Sulfhydryl oxidation induces rapid and reversible closure of the ATP-regulated K+ channel in the pancreatic beta-cell. FEBS Lett. 1993;319:128–132. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80051-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weik R, Neumcke B. ATP-sensitive potassium channels in adult mouse skeletal muscle: characterization of the ATP-binding site. J Membr Biol. 1989;110:217–226. doi: 10.1007/BF01869152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y, Fan Z. Mechanism of Kir6.2 channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification: pore block or allosteric gating? J Physiol. 2002;540:731–741. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapp S, Tucker SJ, Ashcroft FM. Mechanism of ATP-sensitive K channel inhibition by sulfhydryl modification. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:325–332. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.3.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chung JM. An experimental model for peripheral neuropathy produced by segmental spinal nerve ligation in the rat. Pain. 1992;50:355–363. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Q, Sapunar D, Modric-Jednacak K, McCallum JB. Detection of neuropathic pain in a rat model of peripheral nerve injury. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:476–487. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200408000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs A, Rigaud M, Hogan QH. Painful nerve injury shortens the intracellular Ca2+ signal in axotomized sensory neurons of rats. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:106–116. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267538.72900.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapunar D, Ljubkovic M, Lirk P, McCallum JB, Hogan QH. Distinct membrane effects of spinal nerve ligation on injured and adjacent dorsal root ganglion neurons in rats. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:360–376. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200508000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babenko AP, Aguilar-Bryan L, Bryan J. A view of sur/KIR6.X, KATP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 1998;60:667–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees DD, Palmer RM, Hodson HF, Moncada S. A specific inhibitor of nitric oxide formation from L-arginine attenuates endothelium-dependent relaxation. Br J Pharmacol. 1989;96:418–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1989.tb11833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina P, Segarra G, Torondel B, Chuan P, Domenech C, Vila JM, Lluch S. Inhibition of neuroeffector transmission in human vas deferens by sildenafil. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;131:871–874. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghdasi B, Zhang JZ, Wu Y, Reid MB, Hamilton SL. Multiple classes of sulfhydryls modulate the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3739–3748. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.41.25462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]