Secondary BRCA1 mutations in BRCA1-mutated ovarian carcinomas with platinum resistance (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Apr 28.

Abstract

Although ovarian carcinomas with mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 are sensitive to platinum compounds, such carcinomas eventually develop platinum resistance. Previously, we showed that acquired resistance to cisplatin in _BRCA2_-mutated tumors can be mediated by secondary intragenic mutations in BRCA2 that restore the wild-type BRCA2 reading frame. Here, we show that secondary mutations of BRCA1 also occur in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer with platinum resistance. We evaluated 9 recurrent _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancers previously treated with platinum compounds, including five with acquired platinum resistance, one with primary platinum resistance, and three with platinum sensitivity. Four of the 6 recurrent platinum-resistant tumors had developed secondary genetic changes in BRCA1 that restored the reading frame of the BRCA1 protein, while none of 3 platinum-sensitive recurrent tumors developed BRCA1 sequence alterations. We immunohistochemically confirmed restored expression of BRCA1 protein in 2 cases with secondary mutations. Intriguingly, the case with primary platinum resistance showed back mutation of BRCA1 in the primary tumor, and showed another secondary mutation in the recurrent tumor. Our results suggest that secondary mutations in BRCA1 can mediate resistance to platinum in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian tumors.

Keywords: DNA damage and repair mechanisms, BRCA1, BRCA2, cisplatin, drug resistance

Introduction

DNA-crosslinking agents such as cisplatin, carboplatin, melphalan and cyclophosphamide are widely used anti-cancer drugs. Resistance to these agents is a major obstacle to effective cancer therapy. Patients with ovarian cancer usually respond well to initial chemotherapy with cisplatin and its derivative carboplatin, but over time the majority of patients become refractory to platinum-compounds. Ultimately, progression of chemoresistant disease is the major cause of death in women with ovarian carcinoma (1).

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are tumor suppressor genes responsible for familial breast/ovarian cancer. BRCA1 or BRCA2 (BRCA1/2) mutation carriers have increased risks of developing breast and ovarian cancer (2). Ten to 15% of all epithelial ovarian cancers are associated with inherited mutations in BRCA1/2 (3, 4). The vast majority of tumors from women with germline BRCA1/2 mutations demonstrate loss of the wild-type BRCA1/2 allele, and are considered to be BRCA1/2 deficient (5–7).

BRCA1/2-deficient cancer cells are hypersensitive to DNA-crosslinking agents including cisplatin (8–10). Consistently, patients developing _BRCA1/2_-mutated ovarian cancer have a better prognosis compared with non-carriers, if they receive platinum-based therapy (8, 11). However, even _BRCA1/2_-mutated ovarian cancers frequently develop platinum resistance.

Recently, we reported that acquired resistance to cisplatin in _BRCA2_-mutated tumors can be mediated by secondary mutations in BRCA2 that restore the wild-type BRCA2 reading frame (12). _BRCA2_-mutated cancer cells selected in the presence of cisplatin acquired secondary genetic changes on the mutated BRCA2 allele, which canceled the frameshift caused by the inherited mutation and restored expression of functional nearly-full length BRCA2 protein. Cells with secondary mutations were resistant to cisplatin (12). However, mechanisms of cisplatin-resistance in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer remain unclear. Because both BRCA1 and BRCA2 are involved in homologous recombination DNA repair (13, 14) and are required for cellular resistance to cisplatin (9, 10), we hypothesized that similar secondary mutations of the mutated BRCA1 gene mediate acquired resistance to cisplatin in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer. Now we report that secondary mutations of BRCA1 also occur in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer with platinum resistance.

Materials and Methods

Clinical specimens

Three DNA samples from recurrent _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer patients were obtained from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (Los Angeles, CA) through the Pacific Ovarian Cancer Research Consortium. Six DNA samples from _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer patients with recurrent disease were obtained from the tissue bank of University of Washington (Seattle, WA) (Table 1). DNA from UW80, UW40, UWF27, and the recurrent tumor from UW91 were obtained after laser capture microdissection. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and University of Washington. Clinical data of UW40 patient and a cancer cell line derived from the same patient’s recurrent tumor (UWB1.289) have been reported previously (15). Platinum sensitivity was defined as a complete response to treatment maintained without progression for at least six months after platinum therapy. Tumors that were resistant or refractory had progressive disease on platinum therapy, less than a complete response to platinum therapy or progression within 6 months of completing platinum therapy.

Table 1.

Secondary genetic changes of BRCA1 in _BRCA1-_mutated ovarian cancer treated with platinum

| Patient | Inherited mutation | Specimen | Clinical platinum sensitivity | Secondary genetic change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paired specimens | ||||

| CS1 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | sensitive | No | ||

| CS4 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | sensitive | No | ||

| UW91 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | resistant | Yes (back mutation) | ||

| CS14 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | resistant | No | ||

| UW40 | 2594delC | pre-platinum | resistant | Yes (back mutation) |

| post-platinum | resistant | Yes (2606_2628del23) | ||

| UW80 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | resistant | Yes (back mutation) | ||

| UWF27 | 185delAG | pre-platinum | sensitive | |

| post-platinum | resistant | Yes (back mutation) | ||

| Non-paired post-treatment specimens | ||||

| UW208 | 3867G>T (E1250X) | post-platinum | sensitive | No |

| UW317 | 3171insTGAGA | post-platinum | resistant | No |

Sequencing of BRCA1

PCR products of genomic DNA were analyzed for sequence alterations with BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems; Foster City, CA) using ABI 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). All detected mutations were confirmed by sequencing of an independently amplified template. Information of all sequencing and PCR primers for BRCA1 is available in Supplemental Table 1. All nucleotide numbers refer to the wild-type cDNA human sequence of BRCA1 (U14680.1) as reported in the GenBank database.

Immunohistochemical studies

BRCA1 protein was detected in formalin fixed paraffin sections using the mouse monoclonal antibody MS110 (previously called Ab-1, Oncogene Research Products) as previously described (16). The MS110 antibody recognizes an amino terminal epitope at BRCA1 (amino acid residues 89–222) (16). Briefly, paraffin sections were deparaffinized, washed in PBS and treated with steam heat for 20 minutes using antigen target retrieval solution (DAKO). Endogenous peroxidase activity in paraffin sections was quenched by treatment with 3% H2O2 for 5 minutes. Sections were washed with PBS and non-specific binding was blocked by treatment for two hours in 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS. Primary antibody was applied (MS110 at 1:250 dilution) for 14–16 hours at 4°C. Secondary antibody and streptavidin biotin-peroxidase were from the Universal Large Volume LSAB+, Peroxidase kit (DAKO) and were each applied for 30 minutes at room temperature. DAB (3,3′diaminobenzidine)-nickel chromagen (Sigma) was used to visualize antibody complexes and sections were counterstained with hematoxylin. The MS110 antibody can result in non-staining of tissues under certain conditions and can be variable in its results. Therefore, we used non-tumor inflammatory and stromal cells as an internal positive control for BRCA1 protein staining for every section. Decreased protein was only scored if normal cells on the same section were positive. Primary and recurrent tumors were stained side by side under identical conditions. MS110 is the most reliable antibody for the immunohistochemical detection of BRCA1 (16). Because the MS110 antibody recognizes an amino terminal epitope in BRCA1, it cannot distinguish between wild-type BRCA1 protein and truncated non-functional protein resulting from frameshift mutations occurring distal to the antibody’s epitope. Thus, MS110 is not suitable for distinguishing functional versus nonfunctional BRCA1 protein in UW40, UW208, and UW317. Therefore, we evaluated immunohistochemistry in only those tumors with 185delAG mutations (proximal to the antibody’s epitope) for which we had paired primary and recurrent paraffin embedded tumor samples.

Results and Discussion

We analyzed 9 clinical samples of recurrent _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer previously treated with platinum (Table 1). Six of them were clinically platinum-resistant and 3 were platinum-sensitive. One case (UW40) showed primary resistance to platinum, while 5 cases were initially sensitive to platinum and acquired resistance during the disease course. Three of the 5 tumors with acquired platinum resistance (UW80, UW91 and UWF27) and the primarily resistant tumor (UW40) had secondary genetic changes in BRCA1, while none of the three cisplatin-sensitive recurrent tumors showed secondary genetic changes in BRCA1.

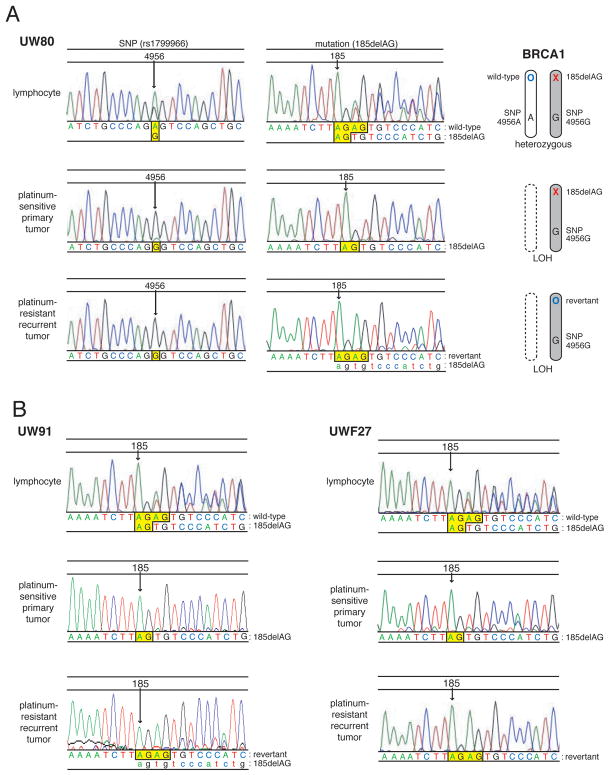

UW80 patient is a heterozygous carrier of a frameshift BRCA1 mutation, 185delAG, which is common in the Ashkenazi Jewish population (17) (Fig. 1A). In the primary tumor specimen, only BRCA1 sequence with 185delAG was detected, indicating that the tumor had lost the wild-type allele. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of an intragenic BRCA1 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) was also confirmed. In the microdissected recurrent tumor from the same patient after development of resistance to platinum, LOH of the BRCA1 SNP was confirmed, indicating that the recurrent tumor contained only the same single allele of BRCA1 as present in the primary tumor and that contamination of non-tumor cells was negligible. In this recurrent sample, wild-type BRCA1 sequence represented >80% of the sequences at the mutation site, suggesting that the recurrent tumor had acquired wild-type BRCA1 by genetic reversion (back mutation to wild-type).

Figure 1. Genetic reversion of BRCA1 mutation in 3 recurrent _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer cases.

A, DNA sequences of BRCA1 in peripheral blood lymphocytes and the primary and recurrent tumors from a patient (UW80) with _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer. In the lymphocytes, a heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) of the BRCA1 locus (4956A/G) was detected, in addition to a heterozygous mutation (185delAG). In the primary tumor, a hemizygous mutation (185delAG) was detected and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of the SNP was confirmed. In the microdissected recurrent tumor, LOH of the SNP was confirmed, but wild-type sequence was 80–90% of the sequences identified at the site of 185delAG. Importantly, the SNP in the recurrent tumor (4956G) is identical to that in the primary tumor (4956G). This indicates that the recurrent tumor had acquired wild-type BRCA1 by genetic reversion (back mutation to wild-type). Residual wild-type sequence could represent heterogeneity in the tumor. A speculative model of BRCA1 alleles in samples from this patient is also depicted.

B, DNA sequences of BRCA1 in peripheral blood lymphocytes, the primary and recurrent tumors from 2 patients (UW91 and UWF27) with _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer. In the lymphocytes, a heterozygous mutation (185delAG) was detected. In the primary tumors, a hemizygous mutation (185delAG) was detected. In the microdissected recurrent tumor specimens, wild-type sequence was detected, suggesting that the recurrent tumors had acquired wild-type BRCA1 by back mutation. Analyses of intragenic SNPs of these cases are shown in Supplemental Figure 1.

Similarly, in 2 more BRCA1.185delAG cases (UW91 and UWF27), the primary tumor demonstrated only mutant sequence with loss of the wild-type allele. In the recurrent tumors, we mainly detected wild-type BRCA1 sequence, suggesting that these two platinum-resistant tumors acquired wild-type BRCA1 by genetic reversion (back mutation to wild-type) (Fig. 1B). Both cases had confirmation of LOH at intragenic SNPs in the primary and recurrent tumors (Supplemental Fig. 1), indicating the presence of a single BRCA1 allele that underwent a secondary genetic alteration.

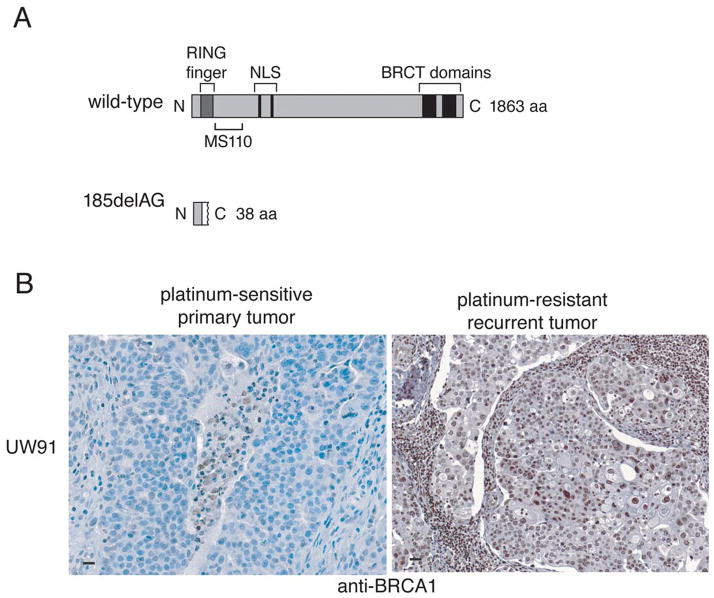

BRCA1.185delAG encodes a severely truncated protein with 38 amino acids, and the back mutation should restore full length BRCA1 protein (Fig. 2A). Consistently, immunohistochemical study revealed that BRCA1 protein expression was absent in the primary tumors of UW80 and UW91, but strongly positive in their recurrent tumors (Fig. 2B and data not shown).

Figure 2. BRCA1 protein expression is restored in recurrent ovarian tumors with genetic reversion of BRCA1 mutation.

A, Schematic presentation of BRCA1 proteins encoded by 185delAG and wild-type BRCA1. Functional domains of BRCA1 protein (RING finger, nuclear localization signals (NLS) and BRCT domains) are depicted. The region that the BRCA1 antibody (MS110) for immunohistochemical staining recognizes (aa 89–222) (16) is also depicted.

B, Immunohistochemical staining of BRCA1 in a primary tumor with BRCA1.185delAG mutation and a recurrent tumor with genetic reversion of the BRCA1 mutation (UW91 patient). The primary tumors are negative for BRCA1 immunostaining, while the recurrent tumors are positive for nuclear BRCA1 immunostaining. Scale bar = 10μm.

The mechanism for genetic reversion of 185delAG mutations in all three tumors is not clear. At the genomic level, the re-insertion of two missing nucleotides would seem less likely to occur than a secondary downstream deletion that corrects the frameshift and restores the open reading frame. Several possible explanations for this phenomenon are not mutually exclusive. First, we speculate that because 185delAG is in a critical portion of the BRCA1 gene close to the RING finger (Fig. 2A), a change of one single amino acid here is likely to have deleterious effect on protein function. Similarly, missense mutations in the RING finger such as C61G can be deleterious (18). Therefore restoration of BRCA1 function may require complete reversion of a mutant in this domain to wild-type. Another possibility is that the particular genomic sequence surrounding 185delAG somehow facilitates the genetic reversion. A third possibility is that other downstream mutations do occur in some tumors but are not detected with our relatively short PCR amplifications. We are unable to do long range PCR that might identify larger genomic events because of the fragmented nature of our DNA. Thus, it is easier to identify genetic reversion in our samples than larger events that restore the open reading frame.

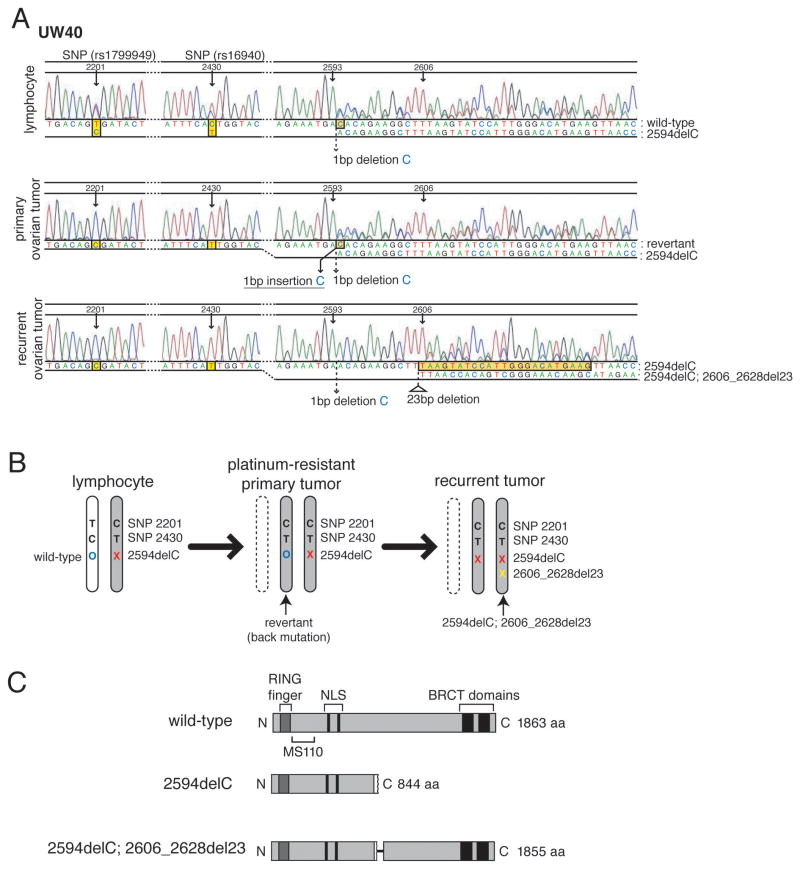

UW40 patient is a heterozygous carrier of a frameshift BRCA1 mutation, 2594delC (Figs. 3A and 3B). The mutant allele encodes an 844 amino acid protein that lacks BRCT domains (Fig. 3C). The patient had a past history of breast cancer at the age of 42 and developed ovarian cancer at age 54. The primary ovarian carcinoma was clinically resistant to platinum. After 6 cycles of platinum and taxol, the patient was treated with taxol for 3 additional cycles with development of progression. She was re-treated with topotecan, then gemcitabine and adriamycin to obtain a partial remission. Recurrent tumor was then obtained at the time of surgery for a fistula.

Figure 3. Genetic reversion of BRCA1 mutation in a primary ovarian tumor with platinum resistance and another secondary BRCA1 mutation in a recurrent tumor of the same patient.

A, DNA sequences of BRCA1 in peripheral blood lymphocytes and the primary and recurrent tumors from a patient (UW40) with _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer. In the lymphocytes, heterozygous SNPs of the BRCA1 locus (2201C/T, 2430T/C) were detected, in addition to a heterozygous mutation (2549delC). In the primary tumor, LOH of the SNPs was confirmed, but the primary tumor specimen shows heterozygous sequence of wild-type BRCA1 and a BRCA1 mutation (2594delC). In the recurrent tumor specimen, LOH of the SNPs was confirmed and mixed sequences of 2594delC and 2594delC;2606_2628del23 were detected.

B, A speculative model of BRCA1 alleles in samples from this patient. The lymphocytes have both the wild-type and mutant (2549delC) alleles. The primary tumor has lost the wild-type BRCA1 allele with SNPs 2201T and 2430C, but has retained the allele with the inherited mutation (2549delC) and SNPs 2201C and 2430T. This mutant allele has been presumably duplicated, and the one of the mutated allele is reverted to wild-type by genetic reversion (back mutation to wild-type). In the recurrent tumor, the allele with wild-type BRCA1 sequence is lost, and the allele with the inherited mutation (2549delC) was again duplicated. One of them obtained a different second mutation (2606_2628del23), which cancels the frameshift caused by the inherited mutation (2549delC). This model explains why we see mixed sequences of BRCA1 in the primary and recurrent tumors.

C, Schematic presentation of BRCA1 proteins encoded by 2594delC and 2594delC;2606_2628del23.

LOH of three intragenic BRCA1 SNPs (2201C/T, 2430T/C, and 2731C/T) that flank the mutation site was confirmed in both the primary and recurrent tumor (Figs. 3A and 3B, and data not shown), indicating that contamination by non-tumor cells was negligible and that both the primary and recurrent tumors had lost one BRCA1 allele. Intriguingly, in the primary tumor, both wild-type BRCA1 sequence and BRCA1 sequence with 2594delC were detected (Figs. 3A and 3B). Careful laser microdissection of a separate second sample of this tumor revealed the same result. The presence of both wild-type BRCA1 sequence and mutant sequence on one allele in the primary tumor suggests that genetic reversion (back mutation to wild-type) occurred on one copy of the mutant allele. We speculate that the presence of the genetically-reverted wild-type allele in the primary tumor contributed to the unusual initial platinum resistance of this tumor. The selective pressure for the genetically reverted tumor cells in the primary ovarian tumor is unknown, but may be related to the 11 months of cyclophoshamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil that the patient previously received for breast cancer. Cyclophosphamide is a DNA cross-linking agent and could exert similar selection pressure for the correction of DNA repair defects as we have observed with exposure to platinum agents.

An alternative explanation for the existence of genetic reversion and other secondary mutations on a mutant allele in this primary tumor is that these events are more common than we appreciate but usually occur in only a small number of primary tumor cells before exposure to chemotherapy. Then, chemotherapy provides the selection pressure for expansion of these sub-clones in recurrent tumors. Perhaps some reports of retention of the wild-type BRCA1/2 allele in breast cancers (19) actually represent genetic reversion. Only careful haplotyping distinguishes tumors with retention of the wild-type allele from those with genetic reversion.

The genetically-reverted wild-type allele was then lost at some point during the disease course. In the recurrent tumor, we could no longer detect wild-type sequence, but we found a second site small deletion (2606_2628del23) in addition to the inherited mutation (2594delC). The second mutation corrects the frameshift caused by the inherited mutation and the allele BRCA1.2594delC;2606_ 2628del23 encodes a BRCA1 protein with intact C-terminal region, which may be functional (Fig. 3C). The actual genomic DNA sequence of BRCA1 in the UW40 recurrent tumor is a mixture of 2594delC;2606_2628del23 and 2594delC without a secondary mutation (Fig. 3A). The mixture of sequences on one allele in both the primary and recurrent tumor may have occurred by secondary genetic alterations (reversion to wild-type in the primary tumor and 23 bp deletion in the recurrent tumor) occurring on just one of the duplicated mutant alleles (Fig. 3B), similar to the situation occurring in Capan-1 clones with secondary mutations of BRCA2 observed in the in vitro experiment in the previous report (12). Alternatively, the two sequences could represent tumor heterogeneity, with only a subset of tumor cells acquiring a secondary mutation on the mutant allele. We favor the explanation of tumor heterogeneity in this case, given that a cell line developed from this recurrent tumor contains only mutant sequence without secondary genetic changes (15).

Taken together, secondary mutations that restore the reading frame of mutated BRCA1 alleles were frequently observed in ovarian tumors with resistance to platinum. These results suggest that secondary mutations of BRCA1 can be a mechanism of acquired resistance to cisplatin in _BRCA1_-mutated ovarian cancer. In addition, the observation of the back mutation of BRCA1 in cisplatin-resistant primary tumor of UW40 patient suggests that secondary mutations of BRCA1 can be a mechanism of primary resistance to cisplatin.

Our studies in this paper and in the previous paper (12) emphasize that BRCA1 and BRCA2 are not only cancer susceptibility genes, but are also critical determinants of clinical sensitivity and resistance to chemotherapy. These studies support the general concept that defective DNA repair leads to chemosensitivity, while restoration of functional DNA repair contributes to acquired chemoresistance in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo.

Testing for secondary mutations in platinum-treated _BRCA1_-mutated cancers may be clinically important, because tumors with secondary mutations are likely to be resistant to platinum and could demonstrate cross-resistance to other agents that exploit BRCA1 defects such as poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 inhibitors. A larger clinical study is warranted to further determine the prevalence and clinical significance of secondary mutations of BRCA1 in _BRCA1_-mutated cancer.

Our finding could have implications for sporadic ovarian carcinoma. Although somatic mutation of BRCA1/2 is rare in sporadic ovarian carcinoma, BRCA1 is reported to be down-regulated in a subset of sporadic ovarian carcinomas by promoter methylation and other unknown mechanisms (20). BRCA2 mRNA expression is reported to be undetectable by reverse transcription PCR in 13% of ovarian carcinoma (20). Therefore, it is tempting to hypothesize that down-regulation of BRCA1/2 causes initial sensitivity to cisplatin, and restoration of functional BRCA1/2 expression by demethylation of the BRCA1 promoter or other mechanisms leads to acquired resistance. Testing this hypothesis will be important to elucidate the more general roles of BRCA1/2 in platinum-sensitivity and resistance.

Supplementary Material

Supp

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA125636 to T.T.) (K08CA96610-01 to E.M.S.), Searle Scholars Program (to T.T.), V Foundation (to T.T.), and Hartwell Innovation Fund (to T.T.), the L&S Milken Foundation (to B.Y.K), the American Cancer Society California Division-Early Detection Professorship (to B.Y.K), and start-up funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (to T.T.) and a gift from the Yvonne Betson Trust (to E.M.S.).

We thank Drs. MC King, T Walsh, CW Drescher, C Jacquemont, and E Villegas for helpful discussion. We thank the Pacific Ovarian Cancer Research Consortium (P50 CA83636, PI: N Urban) for clinical specimens.

Financial support: This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute (R01CA125636 to T.T.) (K08CA96610-01 to E.M.S.), Searle Scholars Program (to T.T.), V Foundation (to T.T.), and Hartwell Innovation Fund (to T.T.), the L&S Milken Foundation (to B.Y.K), the American Cancer Society California Division-Early Detection Professorship (to B.Y.K), and start-up funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center (to T.T.) and a gift from the Yvonne Betson Trust (to E.M.S.).

References

- 1.Agarwal R, Kaye SB. Ovarian cancer: strategies for overcoming resistance to chemotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:502–16. doi: 10.1038/nrc1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li AJ, Karlan BY. Genetic factors in ovarian carcinoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2001;3:27–32. doi: 10.1007/s11912-001-0039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pal T, Permuth-Wey J, Betts JA, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations account for a large proportion of ovarian carcinoma cases. Cancer. 2005;104:2807–16. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Risch HA, McLaughlin JR, Cole DE, et al. Prevalence and penetrance of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a population series of 649 women with ovarian cancer. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:700–10. doi: 10.1086/318787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neuhausen SL, Marshall CJ. Loss of heterozygosity in familial tumors from three BRCA1-linked kindreds. Cancer Res. 1994;54:6069–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Collins N, McManus R, Wooster R, et al. Consistent loss of the wild type allele in breast cancers from a family linked to the BRCA2 gene on chromosome 13q12–13. Oncogene. 1995;10:1673–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gudmundsson J, Johannesdottir G, Bergthorsson JT, et al. Different tumor types from BRCA2 carriers show wild-type chromosome deletions on 13q12–q13. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4830–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foulkes WD. BRCA1 and BRCA2: Chemosensitivity, Treatment Outcomes and Prognosis. Fam Cancer. 2006;5:135–42. doi: 10.1007/s10689-005-2832-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan SS, Lee SY, Chen G, Song M, Tomlinson GE, Lee EY. BRCA2 is required for ionizing radiation-induced assembly of Rad51 complex in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3547–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhattacharyya A, Ear US, Koller BH, Weichselbaum RR, Bishop DK. The breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 is required for subnuclear assembly of Rad51 and survival following treatment with the DNA cross-linking agent cisplatin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:23899–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000276200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boyd J, Sonoda Y, Federici MG, et al. Clinicopathologic features of BRCA-linked and sporadic ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2000;283:2260–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.17.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakai W, Swisher EM, Karlan BY, et al. Secondary mutations as a mechanism of cisplatin resistance in BRCA2-mutated cancers. Nature. 2008 February 10; doi: 10.1038/nature06633. Advanced on line publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moynahan ME, Chiu JW, Koller BH, Jasin M. Brca1 controls homology-directed DNA repair. Mol Cell. 1999;4:511–8. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moynahan ME, Pierce AJ, Jasin M. BRCA2 is required for homology-directed repair of chromosomal breaks. Mol Cell. 2001;7:263–72. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00174-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DelloRusso C, Welcsh PL, Wang W, Garcia RL, King MC, Swisher EM. Functional characterization of a novel BRCA1-null ovarian cancer cell line in response to ionizing radiation. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5:35–45. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson CA, Ramos L, Villasenor MR, et al. Localization of human BRCA1 and its loss in high-grade, non-inherited breast carcinomas. Nat Genet. 1999;21:236–40. doi: 10.1038/6029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Struewing JP, Abeliovich D, Peretz T, et al. The carrier frequency of the BRCA1 185delAG mutation is approximately 1 percent in Ashkenazi Jewish individuals. Nat Genet. 1995;11:198–200. doi: 10.1038/ng1095-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brzovic PS, Meza J, King MC, Klevit RE. The cancer-predisposing mutation C61G disrupts homodimer formation in the NH2-terminal BRCA1 RING finger domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7795–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.7795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King TA, Li W, Brogi E, et al. Heterogenic loss of the wild-type BRCA allele in human breast tumorigenesis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2510–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9372-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hilton JL, Geisler JP, Rathe JA, Hattermann-Zogg MA, DeYoung B, Buller RE. Inactivation of BRCA1 and BRCA2 in ovarian cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1396–406. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supp