Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background:

Tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) is a proinflammatory cytokine involved in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Treatment with TNFα inhibitors reduces disease activity and improves outcomes for patients with RA. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol 400 mg, a novel, poly-(ethylene glycol) (PEG)ylated, Fc-free TNFα inhibitor, as monotherapy in patients with active RA.

Methods:

In this 24-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 220 patients previously failing ⩾1 disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) were randomised 1:1 to receive subcutaneous certolizumab pegol 400 mg (n = 111) or placebo (n = 109) every 4 weeks. The primary endpoint was 20% improvement according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria (ACR20) at week 24. Secondary endpoints included ACR50/70 response, ACR component scores, 28-joint Disease Activity Score Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate 3 (DAS28(ESR)3), patient-reported outcomes (including physical function, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), pain and fatigue) and safety.

Results:

At week 24, the ACR20 response rates were 45.5% for certolizumab pegol 400 mg every 4 weeks vs 9.3% for placebo (p<0.001). Differences for certolizumab pegol vs placebo in the ACR20 response were statistically significant as early as week 1 through to week 24 (p<0.001). Significant improvements in ACR50, ACR components, DAS28(ESR)3 and all patient-reported outcomes were also observed early with certolizumab pegol and were sustained throughout the study. Most adverse events were mild or moderate and no deaths or cases of tuberculosis were reported.

Conclusions:

Treatment with certolizumab pegol 400 mg monotherapy every 4 weeks effectively reduced the signs and symptoms of active RA in patients previously failing ⩾1 DMARD compared with placebo, and demonstrated an acceptable safety profile.

Trial registration number:

Tumour necrosis factor α (TNFα) inhibitors represent a major advance in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treatment and are the first choice in biological therapy for patients following an inadequate response to non-biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).1–5 Although all current TNFα inhibitors have demonstrated similar efficacy in RA clinical trials, individual patient responses to any one or all of these agents vary in clinical practice. Some patients also stop responding to these agents over time or discontinue treatment due to tolerability issues.6 7

Certolizumab pegol is the first poly (ethylene glycol) (PEG)ylated, Fc-free anti-TNFα. Attachment of a PEG chain to the Fab′ fragment increases its half life to a mean of 14 days.8 The lack of an Fc portion may avoid potential Fc-mediated effects such as complement-dependent or antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity as seen in vitro.8 In two studies, certolizumab pegol 200 mg administered every 2 weeks with concomitant methotrexate (MTX) significantly reduced the clinical signs and symptoms of RA, inhibited the progression of structural damage and improved physical function. Improvements in clinical efficacy and inhibition of structural damage were statistically significant at weeks 24 and 52 and were observed as early as weeks 1 and 16, respectively.9 10

Despite evidence of additional efficacy when TNFα inhibitors are combined with MTX, some patients cannot tolerate MTX or have a contraindication to it.11 12 Anti-TNFα monotherapy has been shown to be effective in the treatment of RA.2 13 14 Here we present results from the FAST4WARD (for “eFficAcy and Safety of cerTolizumab pegol – 4 Weekly dosAge in RheumatoiD arthritis”) study, which examined the efficacy (signs and symptoms and patient-reported outcomes) and safety of certolizumab pegol 400 mg monotherapy, administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks, vs placebo in patients with RA who had failed at least one prior DMARD.

METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients, aged 18–75 years, had adult onset RA, defined by the 1987 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria15 of duration ⩾6 months, and had failed ⩾1 prior DMARD due to lack of efficacy or intolerance. Subjects had to have active disease at screening and baseline, defined by ⩾9 (out of 68) tender joints and ⩾9 (out of 66) swollen joints and ⩾1 of the following: ⩾45 min of morning stiffness, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; Westergren method) ⩾28 mm/h, or C-reactive protein (CRP) >10 mg/litre. DMARDs were discontinued for ⩾28 days or five half lives of the drug, whichever was longer, prior to administration of the first study dose, except for leflunomide, which was eliminated using cholestyramine administration followed by a further 28-day washout.

Patients were excluded if they had any inflammatory arthritis other than RA or a history of chronic, serious or life-threatening infection, any current infection, a history of or a chest x ray suggesting tuberculosis or a positive (defined by local practice) purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test. Patients positive for PPD who had received the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination and had a negative chest x ray and no clinical symptoms of tuberculosis could be enrolled.

Patients who had received biological therapies for RA within 6 months, or prior treatment with TNFα inhibitors, were excluded. Concurrent oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalent ⩽10 mg/day, stable for ⩾4 weeks prior to enrolment and during the study), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and analgesics were allowed. Intra-articular, periarticular, intramuscular and intravenous corticosteroids were prohibited.

Study design

FAST4WARD was a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted at 36 sites in Austria, Czech Republic and the USA (June 2003 to July 2004). Institutional review boards or ethics committees approved the protocol at each centre. All patients gave written consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients were randomised 1:1 using an interactive voice randomisation service to lyophilised subcutaneous certolizumab pegol 400 mg or placebo (sorbitol solution) every 4 weeks from baseline to week 20. Solutions of active drug or placebo were prepared by the pharmacist or other unblinded, qualified site personnel, before distributing to blinded study personnel for administration. Patients who completed the study or withdrew on/after week 12 were eligible and encouraged to enter an open label study of certolizumab pegol 400 mg every 4 weeks (unless withdrawn due to non-compliance or possible treatment-related adverse events (AEs)). Patients who withdrew after taking ⩾1 study dose were asked to return for an early withdrawal visit.

Efficacy/safety evaluations

Efficacy and safety were assessed at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24, with additional safety assessments at 4 and 12 weeks post final dose. Additional plasma samples were taken at weeks 21 and 22.

The primary efficacy endpoint was ACR20 response at week 24.16 Secondary endpoints included ACR50/70 response, ACR component scores, Disease Activity Score Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate 3 (DAS (ESR)3), patient-reported outcomes (including physical function (Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI)),17 health-related quality of life (HRQoL), Short-Form 36 item questionnaire (SF-36)18 19), pain (100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS) and modified Brief Pain Inventory (mBPI)) and fatigue (11-point Fatigue Assessment Scale (FAS)20)) and safety.

Post hoc analyses included determination of the proportion of subjects achieving minimal clinically important differences (MCID) in the following at week 24: HAQ-DI (⩾0.22 point decrease from baseline),21 arthritis pain (⩾10 point decrease),22 SF-36 domain (⩾5 point increase in individual domains), Physical and Mental Component Summary (PCS and MCS) scores (⩾2.5 point increase)18 19 and FAS (⩾1 point decrease).23

Safety was assessed by recording all reported AEs at each visit. Treatment-emergent AEs were defined as occurring after the first administration of study drug and up to 12 weeks post final dose. Serious AEs (SAEs) and serious infections were also calculated (post hoc) as the number of new cases per 100 patient years (censored at the time of the first event by preferred term). Laboratory assessments, vital signs, physical examination and autoantibody levels were monitored according to predefined assessment schedules. Plasma concentrations of anti-certolizumab pegol antibodies for all patient samples were measured at a central laboratory (Covance, Chantilly, Virginia, USA) by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay at each safety assessment; samples were considered positive if the level was >2.4 units/ml (lower and upper limits of quantitation were 0.412 and 33.3 µg/ml). Patients who were antibody positive were assessed for neutralising antibodies in a cell-based bioassay (Alta Analytical, San Diego, California, USA).

Statistical analyses

The sample size was based on the expected percent of ACR20 responders; 25% of patients treated with placebo and 50% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol were expected to achieve an ACR20 response at week 24. A sample size of 100 patients per treatment group was estimated to have ⩾90% power to detect a treatment difference of 25% in the ACR20 response rate between the treatment groups at a 5%, 2-sided significance level.

All efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intent to treat (mITT) population (all randomised patients who had taken ⩾1 dose of study medication). The actual number of subjects in the summaries varies slightly from the mITT numbers due to non-imputable missing data for each parameter. For the primary analysis, patients were considered “responders” if they achieved an ACR20 response vs baseline at week 24. Patients who withdrew for any reason were considered non-responders. The proportion of ACR20 responders/non-responders at each visit was compared using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel (CMH) test stratified by country. Several sensitivity analyses of the primary efficacy variable were conducted, including last observation carried forward (LOCF) analysis. Analyses of ACR50 and ACR70 responders were carried out in the same way. Changes from baseline in categorical variables were analysed using the CMH method stratified by country. Actual values and change from baseline at each visit were summarised for continuous variables. Differences in continuous variables between treatment groups were compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), with country and treatment group as factors and baseline score as a covariate. Missing efficacy measurements were imputed using LOCF where available.

As part of the post hoc analyses, the proportions of patients reporting improvements ⩾MCID in patient-reported outcome measures (HAQ-DI, pain VAS, SF-36 and FAS) were compared between treatment groups at each visit using a logistic regression model with treatment as factor and baseline score, age and gender as covariates. The between-group differences in the number of withdrawals due to lack of efficacy were tested using a CMH test stratified by country.

Safety was analysed in the safety population (all randomised patients who received ⩾1 dose of study drug). Analysis of AEs included summaries per the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (version 5.1) coding terms for system organ class, higher level and preferred terms; intensity and relationship to study medication; and by classification as serious or non-serious. AEs leading to death and withdrawal were also assessed.

RESULTS

Patients

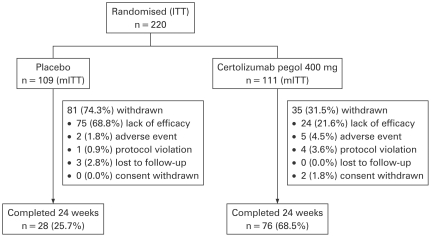

A total of 220 patients with active RA were randomised to certolizumab pegol 400 mg (n = 111) or placebo (n = 109), with 76 (68.5%) and 28 (25.7%) patients in each group, respectively, completing treatment at week 24 (fig 1). Significantly fewer patients who were treated with certolizumab pegol (21.6%) vs placebo (68.8%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy (p<0.001). Patient baseline demographics and disease activity were similar between treatment arms (table 1).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition. Modified intent to treat (mITT) population: all randomised patients who had taken at least one dose of study medication.

Table 1. Baseline patient demographics and disease activity (mITT population).

| Characteristic | Placebo (n = 109) | Certolizumab pegol 400 mg (n = 111) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 54.9 (11.6) | 52.7 (12.7) |

| Female, n (%) | 97 (89.0) | 87 (78.4) |

| RF positive (⩾14 IU/ml), n (%) | 109 (100.0) | 110 (100.0) |

| Disease duration in years, mean (SD) | 10.4 (9.6) | 8.7 (8.2) |

| No of prior DMARDs, mean (SD) | 2 (1.25) | 2 (1.19) |

| Prior MTX use, n (%) | 89 (81.7) | 91 (82.0) |

| Concurrent use of oral corticosteroids (prednisone equivalent ⩽10 mg/day), n (%) | 64 (58.7) | 62 (55.9) |

| Tender joint count, mean (SD) | 28.3 (12.5) | 29.6 (13.7) |

| Swollen joint count, mean (SD) | 19.9 (9.3) | 21.2 (10.1) |

| Patient's Global Assessment of Arthritis, mean (SD) | 3.3 (0.77) | 3.3 (0.75) |

| Physician's Global Assessment of Arthritis, mean (SD) | 3.6 (0.62) | 3.6 (0.67) |

| Patient’s assessment of arthritis pain (VAS), mean (SD) | 54.8 (20.8) | 58.2 (21.9) |

| HAQ-DI, mean (SD) | 1.6 (0.65) | 1.4 (0.63) |

| DAS28(ESR)3, mean (SD) | 6.3 (0.9) | 6.3 (1.1) |

| CRP (mg/litre), geometric mean (95% CI) | 11.3 (8.6 to 14.9) | 11.6 (9.1 to 14.9) |

| ESR (mm/h), geometric mean (95% CI) | 35.6 (30.9 to 41.0) | 30.9 (25.9 to 36.8) |

Although rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity was not an inclusion criterion for the present study, 100% of enrolled patients were RF positive using a threshold value of ⩾14 IU/ml for positivity. A significant number of patients had RF values between 14 and 15 IU/ml, and if a threshold of 15 IU/ml had been used, 76.1% and 75.5% of patients treated with placebo and certolizumab pegol, respectively, would have been considered RF positive.

Efficacy

Primary endpoint

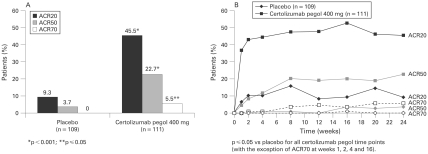

At week 24, using non-responder imputation, certolizumab pegol 400 mg every 4 weeks demonstrated a significantly superior ACR20 response vs placebo (p<0.001; 45.5% vs 9.3%) (fig 2A). Sensitivity analyses of the primary efficacy variable demonstrated ACR20 response rates of 49.1% and 13.9% at week 24, respectively (p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Efficacy of certolizumab pegol: American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response rates (modified intent to treat (mITT) population). A. Treatment with certolizumab pegol 400 mg was statistically significant vs placebo at week 24 for ACR20 and ACR50 (p<0.001) and ACR70 (p⩽0.05). B. ACR20, ACR50 and ACR70 responses with certolizumab pegol 400 mg were statistically significant vs placebo over time (p⩽0.05 at all time points, with the exceptions of ACR70 at weeks 1, 2, 4 and 16).

Secondary endpoints

ACR50 and ACR70

At week 24, using non-responder imputation, ACR50 and ACR70 responses were significantly superior for certolizumab pegol vs placebo (22.7% vs 3.7%; p<0.001; and 5.5% vs 0%, p⩽0.05, respectively) (fig 2A).

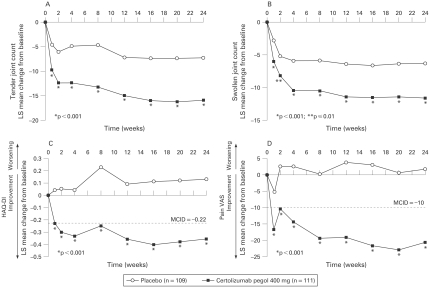

ACR components

Patients treated with certolizumab pegol experienced statistically significant improvements in all ACR components at week 24 vs placebo (p⩽0.05) (table 2, fig 3).

Table 2. Improvement in ACR components and disease activity at weeks 1 and 24: least squares mean change from baseline (mITT population).

| Week 1 | Week 24 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 109) | CZP 400 mg (n = 111) | p Value | Placebo (n = 109) | CZP 400 mg (n = 111) | p Value | |

| ACR core component scores: | ||||||

| Swollen joint count* | −2.8 | −6.0 | <0.001 | −6.3 | −11.6 | <0.001 |

| Tender joint count† | −4.6 | −9.8 | <0.001 | −7.3 | −16.0 | <0.001 |

| Patient's Global Assessment of Arthritis‡ | −0.1 | −0.5 | <0.001 | 0.0 | −0.7 | <0.001 |

| Physician's Global Assessment of Arthritis‡ | −0.1 | −0.7 | <0.001 | −0.2 | −1.1 | <0.001 |

| Patient’s assessment of arthritis pain (VAS)§ | −5.2 | −16.7 | <0.001 | 1.7 | −20.6 | <0.001 |

| HAQ-DI¶ | 0.04 | −0.23 | <0.001 | 0.13 | −0.36 | <0.001 |

| Disease activity: | ||||||

| CRP (mg/litre)** | 1.0 | 0.2 | <0.001 | 1.2 | 0.5 | <0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h)** | 1.0 | 0.7 | <0.001 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.05 |

Figure 3.

Least squares mean change from baseline in American College of Rheumatology (ACR) core component scores (modified intent to treat (mITT) population). Least squares mean change from baseline in (A) tender joint count, (B) swollen joint count, (C) Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) and (D) patient’s assessment of arthritis pain (100-mm visual analogue scale (VAS)) were all statistically significantly superior for certolizumab pegol 400 mg vs placebo from week 1 following administration of study drug and at all time points throughout the 24-week study period (p⩽0.01).

Disease activity

Least squares mean change from baseline in DAS28 (ESR)3 was significantly superior for certolizumab pegol 400 mg vs placebo from week 1 and at all time points through to week 24 (−1.5 vs −0.6, respectively) (p<0.001).

Patient-reported outcomes

Physical function: HAQ-DI

Significant and clinically meaningful improvements (least squares mean change from baseline) in physical function were reported with certolizumab pegol vs placebo from week 1 (−0.23 vs 0.04, respectively) through week 24 (−0.36 vs 0.13, respectively) (table 2 and fig 3C; p<0.001). At week 24, 49% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol reported clinically meaningful improvements in physical function vs 12% for placebo (p<0.001).

Arthritis pain

Significant and clinically meaningful reductions (least squares mean change from baseline) in arthritis pain (VAS) scores were observed in the certolizumab pegol arm vs placebo by week 1 (−16.7 vs −5.2, respectively), and continued to improve throughout the study up to week 24 (−20.6 vs 1.7, respectively) (p<0.001; table 2 and fig 3D). At week 24, 47% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol reported clinically meaningful reductions in arthritis pain vs 17% for placebo (p<0.001). When measured by the mBPI scale, pain was significantly reduced vs placebo by day 2 (p⩽0.05).

HRQoL

Patients receiving certolizumab pegol reported statistically significant improvements in HRQoL at week 24 vs placebo, including all eight SF-36 domains and PCS and MCS scores (p<0.001) (data not shown). At week 24, significantly more patients treated with certolizumab pegol reported HRQoL MCIDs (in all eight domains) vs placebo (p⩽0.01) (data not shown). At week 24, 46% and 34% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol experienced PCS and MCS MCIDs, respectively, vs 16% and 7% for placebo (p<0.001).

Fatigue

Statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements in FAS scores were achieved throughout the 24-week study: least squares mean change from baseline in FAS was −1.69 for certolizumab pegol vs −0.27 for placebo at week 24 (p<0.001). At week 24, 46% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol reported improvements in fatigue of ⩾MCID vs 17% for placebo (p<0.001).

Kinetics of response

Rapid improvement with certolizumab pegol was observed in multiple measures, including ACR20 and ACR50 responses (LOCF imputation; fig 2B), ACR core components (table 2 and fig 3), DAS28, SF-36 and FAS. At week 4 (ie, after a single 400-mg dose), mean tender joint count was reduced from baseline by approximately 40% (from 29.6 to 17.7) with certolizumab pegol vs 14% with placebo (from 28.3 to 24.2); mean swollen joint count was reduced by approximately 38% (from 21.2 to 13.1) vs 16% (from 19.9 to 16.7), respectively (fig 3A,B).

Safety

Treatment-emergent AEs occurred in 57.8% and 75.7% of patients in the placebo and certolizumab pegol groups, respectively (table 3). The majority of AEs in both treatment groups were mild or moderate.

Table 3. Treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs), including serious AEs (safety population).

| Placebo (n = 109) n (%) | Certolizumab pegol 400 mg (n = 111) n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Any AEs | 63 (57.8%) | 84 (75.7%) |

| Intensity: | ||

| Mild | 43 (39.4%) | 62 (55.9%) |

| Moderate | 40 (36.7%) | 52 (46.8%) |

| Severe | 11 (10.1%) | 8 (7.2%) |

| Serious AEs | 3 (2.8%) | 8 (7.2%) |

| Cases/100 patient years* | 9 | 18 |

| Serious infections | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Cases/100 patient years* | 0 | 4 |

| AEs leading to death | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| AEs leading to withdrawal | 2 (1.8%) | 5 (4.5%) |

AEs reported in ⩾5% of patients in the certolizumab pegol groups were headache, nasopharyngitis, upper respiratory tract infections, diarrhoea and sinusitis. SAEs were reported in 3 (2.8%) patients in the placebo group (1 case (0.9%) each of vomiting, chronic renal failure and pneumonitis) and 8 (7.2%) patients in the certolizumab pegol group (2 (1.8%) cases of aggravated RA and 1 (0.9%) each of bacterial arthritis, mastitis, benign parathyroid tumour, postural dizziness, ischaemic stroke and menometrorrhagia) (9 vs 18 cases per 100 patient years, respectively). No cases of tuberculosis or opportunistic infections were reported. The incidence of serious infections was 0% with placebo and 1.8% (two cases) with certolizumab pegol (zero vs four cases per 100 patient years, respectively); the two serious infections in the certolizumab pegol group were bacterial arthritis and mastitis.

There were no reported tumours in the placebo group and two (1.8%), both benign, with certolizumab pegol (one case each of uterine fibroids and benign parathyroid tumour). No malignancies, including lymphoma, or cases of demyelinating disease were reported. AEs leading to withdrawal were reported in two (1.8%) patients treated with placebo (nausea, pneumonitis) and five (4.5%) patients treated with certolizumab pegol (bacterial arthritis, salmonella arthritis, increased blood creatinine/increased blood urea, ischaemic stroke, menorrhagia). No deaths were reported.

Injection site pain was reported in 1.8% and 0% of patients receiving placebo and certolizumab pegol, respectively. Injection site reactions occurred in 13.8% and 4.5% of patients, respectively. Of the patients who received active treatment and had detectable anti-certolizumab pegol antibodies at any time during the study, nine (8.1%) had neutralising antibodies to certolizumab pegol. Clinical studies have demonstrated that in subjects receiving certolizumab pegol, the ACR20 response rate at week 24 was reduced in the population as a whole by approximately 5% as a result of anti-certolizumab pegol antibody formation in subjects receiving certolizumab pegol 400 mg as monotherapy.

No cases of systemic lupus erythaematosus (SLE) or SLE-like disease were reported. Antinuclear autoantibodies (ANA) titres from baseline to week 24 or withdrawal increased in 17% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol compared with 11% of patients treated with placebo, with the majority of patients in both groups (71% and 80%, respectively) showing no change in ANA titres during the 24-week study.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the efficacy of subcutaneous certolizumab pegol 400 mg monotherapy (administered every 4 weeks) in treating the signs and symptoms of active RA in patients who had failed treatment with ⩾1 DMARD, with 45.5% of patients treated with certolizumab pegol achieving an ACR20 response by week 24 vs only 9.3% of patients treated with placebo.

The response to certolizumab pegol was rapid, as significantly more patients achieved ACR20 responses (as well as all other responses, including patient-reported outcomes) as early as week 1 of treatment compared with placebo. Clinical responses were durable and sustained through to week 24. Significantly fewer patients on certolizumab pegol (21.6%) withdrew due to lack of efficacy compared with placebo (68.8%), and withdrawal rates were similar to those observed in previous monotherapy trials.2 14 24 Certolizumab pegol has also been shown to be effective when used in combination with MTX every 2 weeks, with an ACR20 response rate of ∼60%.9 10

Improvements in patient-reported outcomes observed with certolizumab pegol were clinically meaningful, as demonstrated by the proportion of patients with changes ⩾MCIDs for the HAQ-DI, SF-36, pain VAS and FAS. Treatments that reduce RA-related pain and fatigue are important because these symptoms are often cited by patients as having a negative impact on their everyday lives, leading to reduced physical and social function, anxiety and depression, disrupted leisure activities and limitations in employment.20 25 26

Certolizumab pegol was associated with a low incidence of discontinuation due to AEs (4.5%). The rate of serious infections was 1.8% for certolizumab pegol vs 0% for placebo. There were no reports of tuberculosis, opportunistic infections, malignancy (including lymphoma), demyelinating disease or congestive heart failure in either group. The incidence of injection site reactions (4.5%) was low with certolizumab pegol; the incidence of injection site pain (0%) was also low and comparable with placebo. Overall, within the limited of duration of exposure, the AE profile for certolizumab pegol is consistent with other TNFα inhibitors.13 14

Nine (8.1%) patients developed neutralising antibodies to certolizumab pegol. These results are consistent with data reported for other anti-TNFα agents. Formation of antibodies to adalimumab or infliximab have been reported in ∼5% and ∼10%, respectively, of adult patients with RA, and patients who were adalimumab antibody or infliximab antibody positive were more likely to have reduced efficacy.27 28 The ACR20 response rate at week 24 was reduced by only approximately 5% in patients who developed anti-certolizumab pegol antibodies vs the whole population. No autoimmune clinical manifestations (eg, lupus-like syndrome) were observed.

Clinical trials with etanercept29 or adalimumab,30 and observational studies,31 have suggested that using an anti-TNFα agent in combination with MTX is more effective than anti-TNFα monotherapy. Unfortunately, a sizeable subset of patients with RA is intolerant to, or has a contraindication to use of MTX and for these individuals anti-TNF monotherapy can be an important therapeutic option.

The results of this study, demonstrating the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous certolizumab pegol 400 mg every 4 weeks in the absence of concomitant MTX therapy, support the use of anti-TNFα monotherapy as an effective treatment option for patients with RA who cannot tolerate or who have a contraindication to MTX. As the first subcutaneous anti-TNFα agent shown to be effective at once-monthly dosing, certolizumab pegol provides an effective overall treatment for patients with RA, with a rapid, meaningful and durable clinical response and an acceptable safety profile.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the editorial services provided by PAREXEL.

Footnotes

Funding: The FAST4WARD study was funded by UCB. UCB contributed to the design, conduct and reporting of the study.

Competing interests: JV has received a fee from UCB for speaking at a National Congress; RFvV has received consulting fees from UCB; DB has received reimbursement from UCB for attending a symposium and funds for research; JB has received reimbursement from UCB for attending a symposium and funds for research; GC is a full time employee of and holds stocks in UCB; AI is a full time employee at UCB and has shares in the company; NG is a full time employee of UCB and has shares and stock options in the company; VS has worked as an independent biopharmaceutical consultant in clinical development and regulatory affairs since September 1991 and is currently a consultant to various companies, but has not and does not now hold stock in any company. RF has received consulting fees and funds for clinical research from UCB.

Ethics approval: Institutional review boards or ethics committees approved the protocol at each centre. All patients gave written consent, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

REFERENCES

- 1.Maini R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F, Furst D, Kalden J, Weisman M, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomised phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet 1999;354:1932–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, Tindall EA, Fleischmann RM, Bulpitt KJ, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:478–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, Bulpitt KJ, Fleischmann RM, Fox RI, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med 1999;340:253–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, Tannenbaum H, Hua Y, Teoh LS, et al. Radiographic, clinical and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate therapy: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1400–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furst DE, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, Smolen JS, Burmester GR, Sieper J, et al. Updated consensus statement on biological agents for the treatment of rheumatic diseases, 2007. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66(Suppl 3):iii2–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Vollenhoven R, Harju A, Brannemark S, Klareskog L. Treatment with infliximab (Remicade) when etanercept (Enbrel) has failed or vice versa: data from the STURE registry showing that switching tumour necrosis factor alpha blockers can make sense. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:1195–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Watson KD, Symmons DP, Silman AJ. Outcomes after switching from one anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent to a second anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agent in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a large UK national cohort study. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nesbitt A, Fossati G, Bergin M, Stephens P, Stephens S, Foulkes R, et al. Mechanism of action of certolizumab pegol (CDP870): In vitro comparison with other anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha agents. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:1323–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keystone E, van der Heijde D, Mason D, Landewe R, van Vollenhoven R, Combe B, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3319–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolen J, Landewe R, Mease P, Brzezicki J, Mason D, Luijtens K, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:797–804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyrich KL, Watson KD, Silman AJ, Symmons DP. Predictors of response to anti-TNF-alpha therapy among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:1558–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Listing J, Strangfeld A, Rau R, Kekow J, Gromnica-Ihle E, Klopsch T, et al. Clinical and functional remission: even though biologics are superior to conventional DMARDs overall success rates remain low – results from RABBIT, the German biologics register. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnsen AK, Schiff MH, Mease PJ, Moreland LW, Maier AL, Coblyn JS, et al. Comparison of 2 doses of etanercept (50 vs 100 mg) in active rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double blind study. J Rheumatol 2006;33:659–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Putte LB, Atkins C, Malaise M, Sany J, Russell AS, van Riel PL, et al. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab as monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis for whom previous disease modifying antirheumatic drug treatment has failed. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:508–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnett F, Edworthy S, Bloch D, McShane D, Fries J, Cooper N, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Felson DT, Anderson JJ, Boers M, Bombardier C, Furst D, Goldsmith C, et al. American College of Rheumatology. Preliminary definition of improvement in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:727–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirwan JR, Reeback JS. Stanford Health Assessment Questionnaire modified to assess disability in British patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol 1986;25:206–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 health survey manual and interpretation guide. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: New England Medical Center/The Health Institute, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SK. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: New England Medical Center/The Health Institute, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewlett S, Hehir M, Kirwan JR. Measuring fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review of scales in use. Arthritis Rheum 2007;57:429–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraag GR, Baker PR, Groh J, Redelmeier DA. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol 1993;20:557–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain 2008;9:105–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wells G, Li T, Maxwell L, MacLean R, Tugwell P. Determining the minimal clinically important differences in activity, fatigue, and sleep quality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2007;34:280–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, Tesser JR, Schiff MH, Keystone EC, et al A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1586–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hewlett S, Carr M, Ryan S, Kirwan J, Richards P, Carr A, et al. Outcomes generated by patients with rheumatoid arthritis: how important are they? Musculoskeletal Care 2005;3:131–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suurmeijer TP, Waltz M, Moum T, Guillemin F, van Sonderen FL, Briancon S, et al. Quality of life profiles in the first years of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the EURIDISS longitudinal study. Arthritis Rheum 2001;45:111–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abbott. HUMIRA prescribing information, 2008. http://www.rxabbott.com/pdf/humira.pdf (accessed 29 May 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centocor. REMICADE Prescribing Information, 2007. http://www.centocor.com/centocor/assets/remicade.pdf (accessed 29 May 2008) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klareskog L, van der HD, de Jager JP, Gough A, Kalden J, Malaise M, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;363:675–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, Cohen SB, Pavelka K, van Vollenhoven R, et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Vollenhoven RF, Ernestam S, Harju A, Bratt J, Klareskog L. Etanercept versus etanercept plus methotrexate: a registry-based study suggesting that the combination is clinically more efficacious. Arthritis Res Ther 2003;5:R347–R351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]